EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The 2017-2018 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Student Affairs Standing Committee addressed charges related to student wellness and resilience and identified ways where AACP can assist member organizations to build positive wellbeing in students. The Committee report provides nine recommendations to AACP, three suggestions for colleges and schools of pharmacy, and one proposed policy statement related to student wellness and resilience. The report focuses on themes of consequences of burnout and declining resilience, culture shift around wellness, creating community around times of grief, partnerships with member organizations to create campus cultures that promote overall wellbeing and strategies to help students to manage stress in healthy ways. Committee members challenge AACP, and other professional organizations, to include the student voice when future programs and strategies are developed. Finally, this report provides future recommendations for the Student Affairs Standing Committee.

Keywords: KEY TERMS: Student Affairs, Student Wellness, Resilience, Stress Management

INTRODUCTION AND COMMITTEE CHARGES

This standing committee, in accordance with the Association Bylaws, received charges from the Association President.1 President Scott, during his president-elect speech talked about the “WHY” of pharmacy education and challenged members to put the emphasis of discussions around the “WHY”/student which will drive the “WHAT” and “HOW” of education. As a result, President Scott changed the composition of the Student Affairs Standing Committee by adding a student pharmacist to contribute a student perspective to the discussions.2

The committee was formed in 2016-2017 to address charges set forward “regarding admissions, recruitment and student affairs related policies and practices and [to] assist with the development of the Association’s research agenda.”1 Charges for the inaugural committee revolved around a national recruitment campaign and identified methods to help schools and colleges of pharmacy promote student wellness and manage stress.3

Members of the 2017-2018 committee focused on the perceived decline in the overall wellness and resilience of students, and wrestled with best methods to support them.4 A growing body of pharmacy literature identifies student stress levels, stressors and therapeutic interventions. Overall, student stress levels, wellbeing and perceived quality of life have been identified as negative predictors of success and may impair a student’s ability to learn.5 6 7 Similar findings have been reported in medical, nursing and dentistry literature.8 9 10 Members of the committee considered the work of the previous year and reflected on President Scott’s vision to keep students as the focus of our education systems. Four charges related to student wellness emerged as a result:

1. Identify factors contributing to declining student resilience.

2. Identify best strategies and practices on campuses promoting a positive wellbeing.

3. Identify best strategies and practices on campuses for working with students experiencing negative wellbeing.

4. Suggest initiatives AACP might take to assist its member institutions to increase awareness of key issues and enhance student wellbeing.

Committee members were convened at the October 2017 Business Meeting to discuss the charges and identify next steps to accomplish them. A background literature search was completed on the topics of resilience and wellness in advance. Extensive discussions about overall wellness, contributing factors, and the level of resilience among student pharmacists occurred over the day. Members recognized that the culture of pharmacy education may be at odds with the wellbeing of students. Wellbeing is a concern for employers and organizations worldwide, including universities and health-systems that are dedicated to researching and cultivating cultures of wellness. Discussions progressed to the “WHY” pharmacy educators should address the wellbeing of students. Questions, such as how faculty and staff could promote a culture shift within our education system, resulted. Members of the Student Affairs and Academic Affairs Committees met briefly during the day and learned that each had independently identified a similar need for a culture shift in academic pharmacy. The two committees agreed to collaborate on the development of a preamble addressing the needed culture shift within pharmacy education and academic affairs for both reports.

Discussions about resilience and its association with overall wellbeing of our students resulted in a brainstorming about factors that likely increase and decrease student resilience. Factors were subsequently grouped in two categories: intrinsic (internal) and extrinsic (external) factors. These factors will be described in more detail throughout the following pages.

This report, which addresses all committee charges, is divided into three sections. The first section addresses declining student resilience, the second addresses negative wellbeing and the third addresses positive wellbeing. Included within each section are recommendations to the Association and member organizations that align with charge four. Due to the overall inter-linkage between the charges, several recommendations apply to more than one charge.

CHARGE 1: DECLINING STUDENT RESILIENCE

Gray (2015) notes that we have “…raised needy college students who are unable to manage the everyday bumps in the road of life [and] faculty members…struggle to teach and assess them.”4 The committee postulates that different intrinsic and extrinsic factors have led to coping incapabilities within this generation. Students are extrinsically exposed to information and technology with little emphasis on intrinsic reflection or processing in their personal lives. Members theorized that this has led to underdeveloped coping capabilities during stressful situations like those routinely experienced in the rigorous academic settings of pharmacy school. There are many theories surrounding the topic of declining student resilience described in the literature.7 Stressful triggers identified for student pharmacists can be rigorous academic demands, family pressures, financial burdens, poor time management skills, exposure to death on rotations, personal matters outside of school, and ill-prepared faculty and preceptors.11 There are questions and possible further limitations on how or if resilience can be addressed successfully in an academic setting.

The Committee discussed the lack of a centralized resource repository that pharmacy administrators, faculty, staff, and students could access when promoting a culture of wellbeing in pharmacy. Although various techniques, programs, websites, and resources were mentioned and briefly discussed during meetings, a review of the literature and online resources confirmed that there is no individual, comprehensive tool or resource that supports wellbeing within pharmacy education. However, many other resources exist that can be applied to pharmacy (Appendices I and II).

The Committee discussed the need to determine and implement best practices to address declining student resilience. There is little evidence-based research or descriptions of best practices in the literature pertaining to health professional training and none outlining resilience or related topics in pharmacy training specifically. However, Dr. Barbara Fredrickson’s work around the “broaden-and-build” theory which supplements Martin Seligman’s work in positive psychology has had a major influence in understanding resiliency. Dr. Seligman’s work shows positive emotions have inherent value for human growth and broaden “people’s thought-action repertoires,” which then serves to build their life-long personal, physical, intellectual, social and psychological resources.12 Dr. Fredrickson’s work (and the work of many others) suggest that the capacity to experience positive emotions may be a fundamental human strength central to the study of coping and survival, optimizing health and wellbeing and human flourishing.13 14 The broaden-and-build theory suggests that positive emotions can effect cognitive and behavioral skills that build coping skills and positive mental health.15 The research and educational programs available at the University of Pennsylvania and University of North Carolina are good resources that provide coping skills to enhance positive mental health.

While we had one student voice on our committee, we recognized more background information from the student perspective was needed to effectively address the needs of students, faculty, preceptors and staff. It was noted that the American Pharmacists Association – Academy of Student Pharmacists (APhA-ASP) is facing similar concerns within its membership and has adopted a policy related to mental health support. (2017.4 – Efforts to reduce mental health stigma that support the “inclusion and expansion of mental health education and training in the curriculum of all schools and colleges of pharmacy and post-graduate education).16 While partnering with APhA-ASP and other student organizations is important, a concern was raised as to how to identify the needs of less involved students. Potentially, these are some of the most at-risk students so there must be diligence placed on identifying their needs as well. As progress is made to identify student needs, a concerted effort needs to be made to hear voices of various types of students from a variety of schools/colleges of pharmacy and professional organizations. Activities such as focus groups, interviews, and panel discussions could be utilized to help give voice to students’ needs and identify approaches to supporting their wellbeing.

APhA-ASP is not the only professional organization to have policy statements related to resilience and mental health. Other examples include the Association of American Medical Colleges,17 American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine18 and the American Dental Education Association.19 In addition to these organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), formerly the Institute of Medicine, has created an Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience that has over 50 core partner organizations and a network of 80 more that represent all sectors of healthcare and a wide variety of clinicians.20 They are working together to address the challenges currently facing healthcare related to clinician and trainee wellness and resilience.21 Pharmacy is currently being represented by the American Society for Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP).

ASHP, like APhA-ASP, could effectively collaborate with AACP to address this overarching theme of declining resilience. It has oversight of pharmacy residency training and also represents a large cohort of pharmacy practitioners, as well as its position on the NAM Action Collaborative on Clinician Wellbeing and Resilience. Over the last year, ASHP has launched multiple initiatives aimed at helping open discussion around resilience within the profession of pharmacy. In a recent statement by Dr. Abramowitz, ASHP’s CEO, these activities are more clearly outlined22 and reference two recent publications on the topic around burnout and stress among pharmacy residents.23 24 In addition to its activities, ASHP has included a goal within its strategic plan to “improve patient care by enhancing the well-being and resilience of pharmacists, student pharmacists and pharmacy technicians.”25 While the decline in resilience is a current challenge for schools and colleges of pharmacy, it is a challenge for post-graduate and residency training programs as well as the profession of pharmacy at large.

AACP should collaborate across organizations to aid faculty, preceptors, students and staff to address declining resilience and promote self-care.26

POLICY STATEMENT

AACP believes that all administrators, faculty, staff, preceptors, student pharmacists and alumni should contribute to a culture of wellness and resilience in pharmacy education.

RECOMMENDATION 1

AACP should write an Organizational Commitment Statement to be shared with the National Academy of Medicine regarding its plans to help reverse clinician burnout and promote clinician wellbeing.

RECOMMENDATION 2

AACP should open a formal discussion with APhA-ASP leadership and other interested parties to include the student voice and to promote a positive culture of wellbeing within pharmacy.

RECOMMENDATION 3

AACP should continue to feature the topic of wellness and resilience in the Academic Fellows program.

CHARGE 3: ADDRESSING NEGATIVE STUDENT WELLBEING

During our in person meeting, the committee spent time discussing overall student wellness with time dedicated to declining mental health, and negative wellbeing. Pharmacy specific statistics are lacking on the rates of depression, anxiety or other mental health illnesses however, national data highlights young adults are experiencing mental health illnesses at a rate of 22.1% (ages 18-25) and 21.1% (ages 26-49). These age groups encompass the majority of our student body.27 28 Additionally, the 2016 annual survey of the Association for University and College Counseling Centers Directors (AUCCD), an international organization comprised of over 800 members, found rates of anxiety (50.6%) followed closely by depression (41.2%) are predominant and increasing concerns among college students. Suicidal ideation (20.5%) with reports of overall suicide attempts and death by suicide were also reported. The AUCCD reported death by suicide numbers were higher in students who were not engaged in counseling services provided by AUCCD members. This same report identified that of the students who seek services, on average 26.5% take psychotropic medications.45 To further emphasize the growing concern, data reported for medical trainees (students and residents), identify rates for burnout and depression in this cohort to be are higher than peers pursuing other careers. In addition, mental health among this group may decline as training progresses.8 29 30 31 32 33 34

As with medical students, student pharmacists are driven, competitive individuals who are able to pursue many years of intense education. Another connection among these learners is the internal drive for perfection. Henning and colleagues investigated perfectionism and imposter syndrome (IS) in health profession students (dental, medicine, nursing and pharmacy). Their study revealed all groups had high rates of self-prescribed perfectionism however, student pharmacists felt a more socially prescribed need for perfectionism than the other health professions studied (P<0.05), with 50% scoring in the high range in psychological stress. Henning et al also studied IS in this cohort and found it had a significant impact on psychological distress and 30% of the overall cohort of health profession students were in the clinical range for IS.35 It has been previously identified that IS or imposter phenomenon is associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety.36A recent study by Villowck and colleagues within medical students identified a correlation between IS and various components of burnout (exhaustion, cynicism, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization) as well as a correlation between IS and female gender.37 A previous study by Oriel and colleagues confirms the finding of IS and gender connection IS is documented in student pharmacists and may contribute to their rates of burnout, given the similarities in personality traits between medical and pharmacy students.38

Burnout is commonly defined as a syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and diminished feelings of personal accomplishment.22 Burnout can often mimic or be associated with depression as it can result in insomnia, irritability, struggles to concentrate and feelings of “going through the motions.”39 A link between burnout and wellbeing is documented within education and medicinal literature.40 41 There is also a large ongoing discussion and growing body of literature around burnout within healthcare professionals particularly physicians and nurses.22 There is a disturbing connection between burnout and death by suicide within medicine however; this could be extrapolated to others who experience burnout.42 Lastly, there is a documented connection between burnout and patient safety, which is why the topic is now a priority for NAM to identify ways of addressing physicians’/health professionals’ wellbeing.21 Along with the data for IS within student pharmacists, there is a small body of pharmacy literature that has identified rates of burnout among pharmacy practice faculty and has compared burnout between students at distance versus main campus locations.43 44

While there might be a lack of data related to burnout, IS and declining mental health in student pharmacists, there is anecdotal data to suggest that pharmacy has the same challenges. A tragic consequence of declining resilience and negative wellbeing among students is the unnecessary loss of life that can result.45 In the six months that our committee has been actively working together, two member schools represented on this committee lost a student pharmacist to death by suicide. While there is currently no mechanism to track the number of student suicides across pharmacy institutions, subjective evidence suggests they are sadly not uncommon occurrences. The urgency of the recommendations posed within this report is underscored by the loss of life experienced by too many in the academic pharmacy community.

RECOMMENDATION 4

AACP, along with member institutions, should begin a conversation (including students) to explore the stigma around the mental health and suicide of students, staff, and faculty.

SUGGESTION 1

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should encourage faculty and staff to be transparent in sharing their personal stories relative to coping with stress, anxiety, external pressures, and mental illness.

CHARGE 2: PROMOTING POSITIVE STUDENT WELLBEING

Given the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that can influence wellbeing as reflected in NAMs concept model around factors influencing clinician resilience and wellbeing, there needs to be a multipronged approach to promoting positive wellbeing in students that includes individual and system initiatives.22 Additionally, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has been an advocate for creating a culture around positive wellbeing for physicians given the detrimental effects that its absence has on patient care and the healthcare industry.46 He is quoted as saying: “We must also create a culture where discussing and prioritizing emotional well-being are not seen as signs of weakness.” Pharmacy accreditation standards also include guidance around providing wellness education to patients.47 Our committee discussed what some methods are for creating a culture of wellness and teaching our students about positive wellbeing within the curricular constraints we all face.

Looking outside the profession of pharmacy, we find many other sectors such as education, medicine and business that are working to create system-wide approaches to promoting and building positive wellbeing for their employees or users. As an example, corporate America has recognized the benefits of supporting/providing resiliency skills, particularly yoga, meditation, and mindfulness for its own employees. Google created an employee program called Search Inside Yourself, which uses researched and proven techniques to build or enhance mindfulness and emotional intelligence. This program proved so successful within the company that Google is now offering this program to companies and institutions globally.48 The University of Massachusetts School of Medicine has established a similar Center of Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society to “explore, understand, articulate and further mindfulness in the lives of individuals, organizations and communities…”49 Mindfulness and meditation have been found to promote better retention of knowledge, change neuronal pathways in the brain, and decrease stress and anxiety.50 51 52 While this literature is not pharmacy-specific, it is applicable to pharmacy education and practice settings. The committee was pleased to learn that the fall 2018 AACP Institute would focus on the topic of wellbeing and mindfulness among students and faculty to facilitate a shift in the culture of pharmacy education.

Given the strong connection with positive wellbeing and positive mental health, there was also discussion around the mental health needs of our students. Research has shown that in order to successfully address students’ mental health needs on college campuses, administrators should provide outreach campaigns to educate faculty, staff and preceptors on mental health, make available mental health resources on campus known, and have adequate campus counseling services.53 54 In addition, national higher education stakeholders have identified the need to train professionals and students on recognizing the signs and symptoms of negative wellbeing, implement assessments and activities to identify individuals with negative wellbeing, and decrease the stigma related to mental health.55 56 57 58

Gatekeeper-trainings are intended to educate and train individuals on recognizing the signs and symptoms of stress, and respond to individuals that may be dealing with a mental health issue. Such trainings have been shown to have positive outcomes on participants’ self-evaluation and confidence.59 60 One such training is Mental Health First Aid, which was utilized with pharmacy students at the University of Sydney.61 It was discovered that students trained in this program demonstrated reduced stigmatizing attitudes associated with mental illness, recognized mental illness more readily, and felt more confident in interacting with patients with mental health issues in the clinical setting. 30 This understanding is important as pharmacists are the most accessible healthcare providers and are assisting mental health patients with their medications and treatment regimens.

Similar programs assist in the recognition of individuals dealing with mental health issues and promote outreach to them. Data suggests that the majority of college students with mental health issues do not receive appropriate treatment.29 62 Colleges and schools of pharmacy should institute efforts that remove barriers and encourage students to participate in mental health wellness programs.

To this end, the committee discussed many ways of creating programming for students, faculty and preceptors that equip them with strategies for promoting positive wellbeing in their learners, as well as themselves.63 This committee has also created a set of appendices to help schools and/or colleges of pharmacy in their efforts to develop programming around positive wellbeing.

RECOMMENDATION 5

AACP should develop programming and resources to assist schools in developing activities and tools to help students and faculty successfully integrate self-awareness, self-care, wellbeing, and resilience as part of professional development.

RECOMMENDATION 6

The AACP Board of Directors should form a task force to create a white paper on the topic of wellness and resilience and to build related core competencies.

RECOMMENDATION 7

AACP should collaborate with other appropriate organizations to train faculty, staff, preceptors, and other practitioners to embrace and teach self-care practices.

SUGGESTION 2

Faculty, students, preceptors, and staff in colleges and schools of pharmacy should focus on learner self-reflection and self-discovery to promote a culture of wellbeing for themselves and their institution.

RECOMMENDATION 8

AACP should partner with other organizations to provide regional training sessions on the topic of wellness and resilience for colleges and schools of pharmacy.

RECOMMENDATION 9

The 2019 AACP Teachers Seminar should focus on the theme of wellness and resilience.

SUGGESTION 3

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should review their curricula to ensure the successful integration of self-awareness, self-care, wellbeing, and resilience into the CORE curriculum.

CONCLUSION (or CALL TO ACTION)

This committee has made headway in starting discussions and collaborations around the topic of student wellness and resilience. There has been a focus placed on the “WHY”/student, and more needs to be done to capture their voice in future discussions. A culture shift within our profession to promote overall wellness for students, faculty, preceptors, and staff is needed. This in turn can help with professional longevity and retention, and ensure that high quality patient care is delivered in all settings. AACP is well positioned to help lead and coordinate efforts across organizations. Development of programming targeted at administrators, faculty, staff and preceptors is needed to promote positive wellbeing, enhance resilience, and reduce stress among our students. This committee has compiled selected resources in Appendices 1 and 2 that member organizations can use to create their own programming around wellness. Finally, the Student Affairs Standing Committee recommends the following be addressed by a future Student Affairs Standing Committee or other AACP member group:

• Partner with APhA-ASP on student wellness and strategies to promote it.

• Create a call for evidence-based and emerging practices of stress management and promotion of positive wellbeing from member organizations.

• Begin a dialogue with student pharmacists across member organizations to learn their needs, perceptions, and recommendations to support and promote student wellbeing.

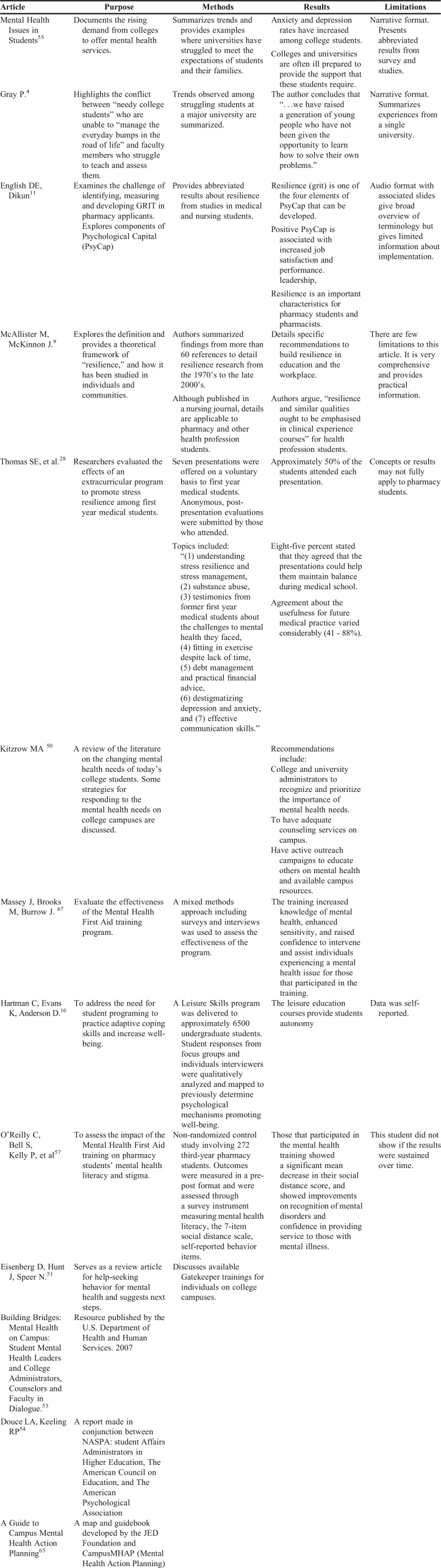

Appendix 1. Annotated Bibliography of Mental Health and Wellbeing Resources

Appendix 2. Additional Mental Health and Wellbeing Resources

a. Student Stories: A seven minute “compelling video” from the Chronicle of Higher Education of students discussing anxiety/depression. Five students discuss what it is like to be a college student managing anxiety in this compelling video. “The students’ stories are personal, but the challenges they face are far from uncommon. Rates of anxiety and depression have risen among college students, straining campus counseling resources. One argument for faculty involvement: Students’ mental-health struggles can have real implications for their learning. One student in the video describes the connection between anxiety and missing class and anxiety and depression are associated with lower grades and higher rates of dropping out.” Students Share How They Cope and How Campuses Can Help by Julia Schmalz, December 11, 2017. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Facing-Anxiety/241968?cid=tn&elqTrackId=113170ce7f0b4be68efa13c1523fe2da&elq=926c7d051aae46a39502e994489835ec&elqaid=17306&elqat=1&elqCampaignId=7536

b. University of Penn Positive Psychology Center http://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/. This is the world premier source for Martin Seligman’s Positive Psychology and the Penn Resiliency Program and workshops, which are evidence-based training programs that have been demonstrated to build resilience, well-being, and optimism. Also for faculty, see http://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/resources/course-syllabi-teachers.

c. University of California Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center for the science/practices that relate to all audiences https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/. See their Greater Good Magazine: Science-based Insights for a Meaningful Life. Lively website includes user-friendly quizzes and short videos with University and guest faculty.

d. Stanford University’s Learning Connection is a resiliency based service for students “The Resilience Project combines personal storytelling, events, programs, and academic skills coaching to motivate and support you as you experience the setbacks that are a normal part of a rigorous education.” http://learningconnection.stanford.edu/resilience-project.

e. University of Massachusetts Medical School Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care and Society. https://www.umassmed.edu/cfm/. This is the global resource center created in the School of Medicine, Division of Mindfulness by Jon Kabat-Zinn for mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) and the Therapeutic Neuroscience Lab for realizing human potential.

f. National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resiliency. In response to alarming evidence of high rates of depression and suicide among U.S. health care workers, the National Academy of Medicine is launching a wide-ranging “action collaborative” of multiple organizations to promote clinician well-being and resilience. To date, more than 20 professional and educational organizations have committed to the NAM-led initiative to identify priorities and collective efforts to advance evidence-based solutions and promote multidisciplinary approaches that will reverse the trends in clinician stress and ultimately improve patient care and outcomes. The collaborative began work in January 2017; public workshops and meetings are scheduled throughout the year. See https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being.

g. The Alliance for Student-Led Wellbeing comprises United Kingdom “organizations that aim to raise awareness about the importance of good mental health, reduce the stigma associated with anxiety and depression and provide practical help and emotional support to university and college students, working alongside campus and public services.” https://alliancestudentwellbeing.weebly.com/. Note: The UK has had a major push on mental health (see the YouTube video of the young royals discussing their own mental health https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=45RqUmxDXiY).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bylaws for the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Approved by AACP House of Delegates, July 2017. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/aacp_bylaws_revised_july_2017.pdf. Published July 2017. Accessed February 14, 2017.

- 2. Scott S. Opening Remarks. 2017 AACP House of Delegates. July 2017.

- 3.Chesnut RJ, Atcha II, Do DP, et al. Report of the 2016-2017 Student Affairs Standing Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpeS12. doi:10.5688/ajpes12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray P. Declining student resilience: a serious problem for colleges. Psychology Today. September 2015. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/freedom-learn/201509/declining-student-resilience-serious-problem-colleges. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 5.Payakachat N, Gubbins PO, Ragland D, Flowers SK, Stowe CD. Factors associated with health-related quality of life of student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Ed. 2014;78(1):7. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7817. doi:10.5688/ajpe7817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Votta RJ, Benau EM. Predictors of stress in doctor of pharmacy students: results from a nationwide survey. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2013;5(5):365–372. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leblanc VR. The effects of acute stress on performance: implications for health professions education. Academic Medicine. 2009;84(Supplement) doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b37b8f. doi:10.1097/acm.0b013e3181b37b8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students. JAMA. 2016;316:2214–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAllister M, McKinnon J. The importance of teaching and learning resilience in the health disciplines: a critical review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29(4):371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.10.011. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverstein S, Kritz-Silverstein D. A longitudinal study of stress in first-year dental students. J Dental Educ. 2010;74(8):836–848. http://www.jdentaled.org/content/74/8/836/tab-article-info [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.English DE, Dikun JA. 2017. Resilience: An Essential Component of Today’s Pharmacist. Webinar from www.aacp.org. http://connect.aacp.org/viewdocument/resilience-an-essential-component-1.

- 12.Seligman MEP. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: Free Press; 2002.

- 13.Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychologist. 2001;56(3):218–226. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartman C, Evans K, Anderson D. Promoting adaptive coping skills and subjective well-being through credit-based leisure education courses. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 2017;54(3):303–315. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fredrickson BL. Broaden-And-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. doi:10.4135/9781412956253.n75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.American Pharmacists Association. APhA Academy of Student Pharmacists – House of Delegates Report of the 2017 APhA‐ASP Resolutions Committee – Full Report. http://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/Report%20of%20the%202017%20APhA-ASP%20Resolutions%20Committee%20-%20Full%20Report.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

- 17.AAMC Statement on Commitment to Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2017. https://www.aamc.org/download/482732/data/aamc-statement-on-commitment-to-clinicianwell-beingandresilience.pdf.

- 18.AACOM Releases Statement on Clinician Well-Being. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Press Releases and Statements. October 2017. http://www.aacom.org/news-and-events/press-releases-and-statements/press-release-details/2017/10/31/aacom-statement-on-clinician-well-being. Accessed April 3, 2018.

- 19.ADEA Governance Documents and Publications. American Dental Education Association. http://www.adea.org/about_adea/governance/Pages/ADEAGovernanceandPublications.aspx. Accessed April 12, 2018.

- 20.Clinician Resilience and Well-being. National Academy of Medicine. https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/. Accessed April 13, 2018.

- 21.Brigham T, Barden C, Dopp AL, et al. A Journey to Construct an All-Encompassing Conceptual Model of Factors Affecting Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. NAM Perspectives, Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://nam.edu/journey-construct-encompassing-conceptual-model-factors-affecting-clinician-well-resilience/. Published January 28, 2018. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- 22.Abramowitz P. ASHP Leading the Way on Well-Being & Resilience. ASHP Connect. April 2018. https://connect.ashp.org/blogs/paul-abramowitz/2018/04/09/ashp-leading-the-way-on-well-being-resilience?ssopc=1. Accessed April 12, 2018.

- 23.Bridgeman P, Bridgeman MB, Barone J. Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. Am J Health-System Pharmacy. 2018;75(3):147–152. doi: 10.2146/ajhp170460. doi:10.2146/ajhp170460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silvester JA, Cosme S, Brigham TP. Adverse impact of pharmacy resident stress during training. Am J of Health-System Pharmacy. 2017;74(8):553–554. doi: 10.2146/ajhp170083. doi:10.2146/ajhp170083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ASHP Strategic Plan. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. https://www.ashp.org/About-ASHP/What-We-Do/ASHP-Strategic-Plan. Published September 29, 2017. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- 26.Thomas SE, Haney MK, Pelic CM, Shaw D, Wong JG.Developing a program to promote stress resilience and self-care in first-year medical students Canadian Medical Educ J 201121e32–e36.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3150750/. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Illness Mental. National Institute of Mental Health Web site. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml. Published November 2017. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- 28.Reeze DR, Bershad C, LeViness P, Whitlock M. The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors Web site. AUCCCD Annual Survey. July 2016. https://www.aucccd.org/assets/documents/aucccd%202016%20monograph%20-%20public.pdf.

- 29.Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314:2373–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. NAM Perspectives, Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://nam.edu/Burnout-Among-Health-Care-Professionals. Published July 25, 2016. Accessed on April 4, 2018.

- 31.Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Jr., Eacker A, et al. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA. 2010;304:1173–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1318. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carson AJ, Dias S, Johnston A, et al. Mental health in medical students. A case control study using the 60 item General Health Questionnaire Scott Med J 2000. Aug454115–6.doi.org/10.1177/003693300004500406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students Ann Intern Med 2008. Sep 21495334–41.doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the impostor phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):456–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00234.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chrisman SM, Pieper WA, Clance PR, Holland CI, Glickauf-Hughes C. Validation of the Clance Imposter Phenomenon Scale. J Personality Assess. 1995;65(3):456–467. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_6. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villwock JA, Sobin LB, Koester LA, Harris TM. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:364–369. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5801.eac4. doi:10.5116/ijme.5801.eac4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oriel K, Plane MB, Mundt M. Family medicine residents and the impostor phenomenon. Fam Med. 2004;36:248–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCray LW, Cronholm PF, Bogner HR, Gallo JJ, Neill RA. Resident physician burnout: is there hope? Fam Med. 2008;40:626–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu H, Liu L, Sun W, Zhao X, Wang J, Wang L. Factors related to burnout among Chinese female hospital nurses: cross-sectional survey in Liaoning Province of China. J Nursing Manag. 2012;22(5):621–629. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12015. doi:10.1111/jonm.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasmussen V, Turnell A, Butow P, et al. Burnout among psychosocial oncologists: an application and extension of the effort-reward imbalance model. Psychooncology. 2015;25(2):194–202. doi: 10.1002/pon.3902. doi:10.1002/pon.3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Acad Med. 2014;89:443–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Ibiary SY, Yam L, Lee KC. Assessment of burnout and associated risk factors among pharmacy practice faculty in the United States. AJPE. 2017;81(4) doi: 10.5688/ajpe81475. Article 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ried LD, Motycka C, Mobley C, Meldrum M. Comparing self-reported burnout of pharmacy students on the founding campus with those at distance campuses. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(5):114. doi: 10.5688/aj7005114. doi:10.5688/aj7005114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.AAS Youth Suicidal Behavior Fact Sheet. American Association of Suicidology Web site. http://www.suicidology.org/Portals/14/docs/Resources/FactSheets/2011/YouthSuicidalBehavior2014.1.pdf. Published 2011. Updated 2014. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- 46.Berg S, Vivek Murthy., MD turns focus to physician well-being. AMA Wire. https://wire.ama-assn.org/life-career/vivek-murthy-md-turns-focus-physician-well-being. Published September 25, 2017. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 47.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2018.

- 48.Mindfulness and Emotional Intelligence Leadership Training. Google Search Inside Yourself. https://siyli.org/. Accessed April 12, 2018.

- 49.Center of Mindfulness in Medicine. Health Care, and Society. University of Massachusetts Medical School. https://www.umassmed.edu/cfm/about-us/. Published June 24, 2014. Accessed April 13, 2018.

- 50.Cohen J. Social. emotional, ethical, and academic education: creating a climate for learning, participation in democracy, and well-being. Harvard Educ Review. 2006;76(2):201–237. doi:10.17763/haer.76.2.j44854x1524644vn. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davidson JD, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, et al. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(4):564–570. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3. July . doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000077505.67574.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Desrosiers A, Vine V, Klemanski DH, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Mindfulness and emotion regulation in depression and anxiety: common and distinct mechanisms of action. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30(7):654–661. doi: 10.1002/da.22124. doi:10.1002/da.22124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kitzrow MA. The mental health needs of today’s college students: challenges and recommendations. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 2003;(1):41. doi:10.2202/1949-6605.1310. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eisenberg D, Hunt J, Speer N. Help seeking for mental health on college campuses: review of evidence and next steps for research and practice. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):222–232. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.712839. doi:10.3109/10673229.2012.712839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. A Guide to Campus Mental Health Action Planning. The Jed Foundation Web site. https://www.jedfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/campus-mental-health-action-planning-jed-guide.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed on March 15, 2018.

- 56. Building Bridges: Mental Health on Campus: Student Mental Health Leaders and College Administrators, Counselors, and Faculty in Dialogue. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://permanent.access.gpo.gov/gpo14635/SMA07-4310.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed January 15, 2018.

- 57.Douce LA, Keeling RP. A strategic primer on college student mental health. American Council on Education. 2014. https://www.apa.org/pubs/newsletters/access/2014/10-14/college-mental-health.pdf.

- 58.Mental health issues in students. Chron Higher Educ. https://www.chronicle.com/items/biz/pdf/ChronFocus_MentalHealthv5_i.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- 59.Eisenberg D, Hunt J, Speer N. Help seeking for mental health on college campuses: review of evidence and next steps for research and practice. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):222–232. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.712839. doi:10.3109/10673229.2012.712839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oreilly CL, Bell JS, Kelly PJ, Chen TF. Impact of mental health first aid training on pharmacy students knowledge, attitudes and self-reported behaviour: a controlled trial. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;45(7):549–557. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.585454. doi:10.3109/00048674.2011.585454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kitchener BA, Jorm AF. Mental health first aid training for the public: evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry. 2002;2(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-2-10. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Drum DJ, Brownson C, Burton Denmark A, Smith S. New data on the nature of suicidal crises in college students: shifting the paradigm. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2009;40:213–22. doi:10.1037/a0014465. [Google Scholar]

- 63. A Guide to Campus Mental Health Action Planning. The Jed Foundation Web site. https://www.jedfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/campus-mental-health-action-planning-jed-guide.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed on March 15, 2018.