Abstract

Background:

Factors influencing patient satisfaction with a transtibial prosthesis have been studied fragmentarily. The aims of this systematic review were to review the literature regarding factors of influence on patient satisfaction with a transtibial prosthesis, to report satisfaction scores, to present an overview of questionnaires used to assess satisfaction and examine how these questionnaires operationalize satisfaction.

Methods:

A literature search was performed in PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Cochrane, and Web of Knowledge databases up to February 2018 to identify relevant studies.

Results:

Twelve of 1832 studies met the inclusion criteria. Sample sizes ranged from 14 to 581 participants, mean age ranged from 18 to 70 years, and time since amputation ranged from 3 to 39 years. Seven questionnaires assessed different aspects of satisfaction. Patient satisfaction was influenced by appearance, properties, fit, and use of the prosthesis, as well as aspects of the residual limb. These influencing factors were not relevant for all amputee patients and were related to gender, etiology, liner use, and level of amputation. No single factor was found to significantly influence satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Significant associations were found between satisfaction and gender, etiology, liner use, and level of amputation.

Conclusion:

Relevance of certain factors for satisfaction was related to specific amputee patient groups. Questionnaires assessing satisfaction use different operationalizations, making comparisons between studies difficult.

Keywords: amputation, prosthesis fitting, questionnaires, satisfaction

1. Introduction

Regaining mobility is an important rehabilitation objective for patients with a transtibial amputation. Satisfaction with the prosthesis plays a key role in regaining mobility and is important for optimizing use of the prosthesis, preventing rejection, and increasing compliance with the medical regimen.[1,2] Forty percent to 60% of amputee patients are not satisfied with their prostheses.[3,4] Fifty-seven percent are dissatisfied with the comfort of their prostheses, and over 50% report pain while using their prostheses.[3,4] Rejection of the prosthesis can be seen as the ultimate expression of dissatisfaction with the prosthesis and occurs in up to 31% cases of prostheses prescribed to armed forces service members with lower limb amputations, mainly as a result of technical problems (e.g., “too much fuss” during use and the prosthesis being “too heavy”).[5] These findings make (dis)satisfaction with transtibial prostheses a highly relevant issue in lower limb amputee care.[4,5]

Patient satisfaction is a key indicator of the quality of care. It plays an important role in the evaluation of outcomes of health care services and management of the health care budget.[1,2,6–8] Numerous theories and models of patient satisfaction exist, including “the value expectancy model,” “the disconfirmation theory,” “the attribution theory,” and “the need theory.” [6,8] Satisfaction is defined in different ways, for example, “an emotional or affective evaluation of the service based on cognitive processes which were shaped by expectations”; “a congruence of expectations and actual experiences of a health service”; and “an overall evaluation of different aspects of a health service.” [6] In summary, patient satisfaction entails matching patients’ experiences with their expectations.

The various questionnaires assessing satisfaction with the prosthesis operationalize satisfaction differently. For example, the Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales (TAPES) assesses satisfaction using a 5-point scale that comprises questions on “color,” “noise,” “shape,” “appearance,” “weight,” “usefulness,” “reliability,” “fit,” “comfort,” and “overall satisfaction.” [9,10] The Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire (PEQ) uses 2 visual analogue scales to assess overall satisfaction and satisfaction with walking with the prosthesis during the previous 4 weeks.[1]

In this review, prosthesis satisfaction is viewed as a multidimensional and dynamic construct. Prosthesis satisfaction is the patient's subjective and emotional evaluation of (aspects of) the prosthesis that is influenced by the appearance, properties, fit, and use of the prosthesis, as well as aspects of the residual limb. Emotions regarding the prosthesis are also influenced by the patient's psychological state, for example, depression and anxiety; psychological factors; and person-related characteristics, such as prior experiences, coping, expectations, general values, beliefs, perceptions, and social context.[6,7] Hence, satisfaction with the prosthesis (or prosthesis components) is a biopsychosocial construct that is influenced by all of the aforementioned factors.[1,2,6,7]

Recently, a systematic review analyzed patients’ experiences, including satisfaction, with transtibial prosthetic liners.[11] This review has several limitations. First, half of the included studies had small sample sizes (≤10). Second, most of the included studies used author-designed questionnaires, some of which were based on the PEQ. Third, satisfaction was not studied in all of the included studies. Fourth, in several studies, patients’ experiences with liners were assessed with test prostheses instead of definitive prostheses. Finally, in 2 studies, the same population was researched.[12,13]

Given that prosthesis satisfaction is not only interpreted differently by researchers [1,2,6] but also operationalized differently in questionnaires, it is difficult to compare results of studies on prosthesis satisfaction. A comprehensive overview of factors that influence satisfaction with the prosthesis is currently missing. Such an overview will help clinicians to systematically assess these factors and target them to improve outcomes.

This systematic review aims to identify factors of influence on patient satisfaction with a definitive transtibial prosthesis, report satisfaction scores, present an overview of questionnaires used to assess satisfaction with the prosthesis, and examine how these questionnaires operationalize satisfaction.

2. Methods

This study is reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. Ethical approval is not required for this is a systematic review of previously published studies.

2.1. Search strategy

Six databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Cochrane, and Web of Knowledge) were searched from their inception to February 2018. The search strategy used for PubMed was based on terms related to lower limb prosthesis, including “lower limb,” “leg,” “artificial limb,” and “prosthesis”; and patient satisfaction, including “patient satisfaction,” “acceptance,” “rejection,” “satisfaction,” and “dissatisfaction.” Excluded were the terms “endoprosthesis,” arthroplasty,” “graft,” “implant,” and “breast.” With the aid of an information specialist, the search strategy for MEDLINE was designed: (leg OR lower limb) AND (prosthesis OR artificial limb) AND (patient satisfaction OR accept∗ OR reject∗ OR satisf∗ OR dissatisf∗) NOT (endoprosthesis OR implant OR graft OR bypass OR breast). The search strategy was adapted for each of the databases accordingly.

2.2. Study selection

Studies were collected in a RefWorks database and duplicates (publications listed more than once) were removed. Two observers (JG, EB) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the studies identified in the databases.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: a questionnaire was used to assess patient satisfaction with a definitive prosthesis; the transtibial amputation level was studied, or, in case of mixed samples, separate data were presented on transtibial amputee patients; age of (part of) the study population was > 18 years and separate data were presented on this group; sample size was > 10; and studies were published in English, Dutch, or German.

Excluded were studies of interim or test prostheses, congress abstracts with no full text available, and all types of reviews. After title and abstract assessment, observer agreement was calculated (Cohen Kappa and absolute agreement), and discrepancies in assessments were discussed between observers until consensus was reached. Full text studies included in the first round were assessed independently for inclusion and exclusion criteria by the same observers (JG, EB) and recorded on a predesigned form. Next, a consensus meeting took place to discuss the recorded studies. Double publications (studies using the same study population) were removed. Reference lists of included studies were checked for any relevant studies not identified in the database searches. The full text of these studies was assessed and interobserver agreement was calculated.

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed independently by 2 authors (ES, EB) by means of a checklist based on the Methodology Checklist for Cross-Sectional/ Prevalence Studies of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[14] For longitudinal studies, additional criteria from the Methodological Index of Non-Randomized Studies (Minors check list) were assessed.[15] When relevant data were missing or a mixed group of amputee patients was described in the study and no separate data on transtibial amputee patients were presented, we contacted the corresponding authors with the request to provide these data.

Factors associated with prosthesis satisfaction were extracted independently by 2 observers (ES, EB) and recorded on a predesigned form. These factors were categorized into 5 satisfaction domains: appearance of the prosthesis, properties of the prosthesis, fit of the prosthesis, use of the prosthesis, and aspects of the residual limb.

2.3. Questionnaires

Two observers (ES, a rehabilitation psychologist with 17 years of experience in rehabilitation care, and EB, a physiatrist with 18 years of experience in amputee patient care) independently analyzed the questionnaires used in the studies regarding questions or combinations of questions that assessed prosthesis satisfaction. Questions that asked the patient to subjectively or emotionally evaluate the appearance and properties of the prosthesis or its fit and use were labeled as satisfaction questions. For example, the question “Rate how your prosthesis looks,” with answering possibilities on a visual analogue scale anchored by “terrible/excellent,” was labeled as a satisfaction question. If responses to a question were endorsed on a numerical scale, for example, “How many prostheses wore out?”, this question was not labeled as a satisfaction question. Discrepancies in assessment of questions were discussed until consensus was reached.

3. Results

3.1. Search

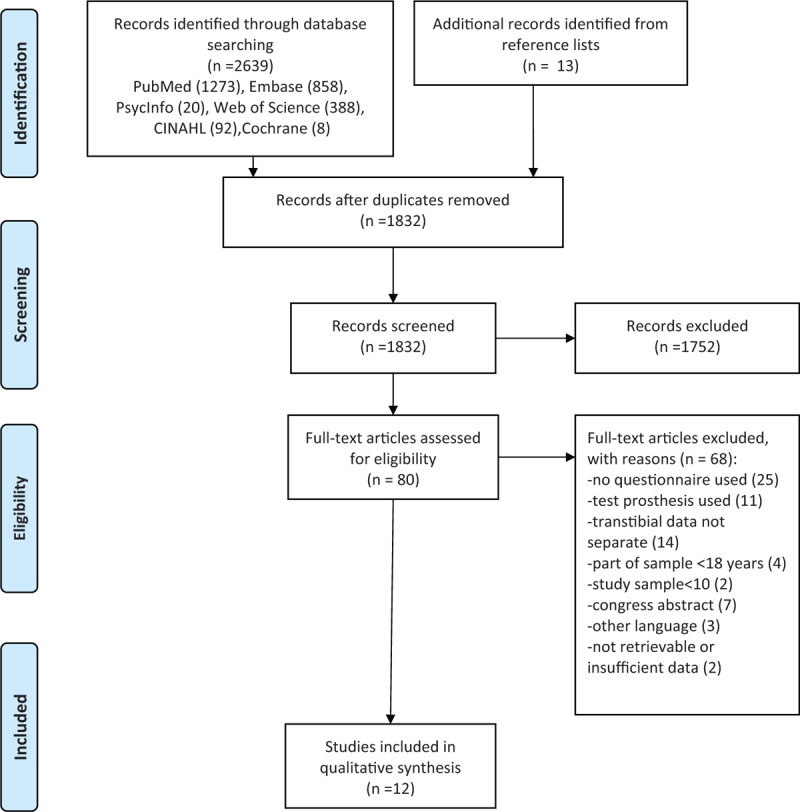

A total of 1832 unique studies were identified for assessment after removal of duplicates from the search results. Thirteen studies were identified from the reference lists of the included studies (Fig. 1). Cohen Kappa as a measure for interobserver agreement for title and abstract assessment was 0.793, absolute agreement 98%. Eighty studies remained after the first assessment and full text of these studies was retrieved, in addition to the full text of studies identified from the reference lists. Sixty-seven studies were excluded (Fig. 1).[10,13,16–76] The assessment resulted in the final inclusion of 12 studies (Fig. 1).[1,3–5,77–84] Cohen Kappa as a measure for interobserver agreement of the full text assessment and selection was 0.39 (absolute agreement 67%).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of paper assessment.

3.2. Study descriptions and quality assessment

Most studies had a cross-sectional design. Two had a longitudinal design.[79,84] Sample sizes varied from 14 to 581 participants, age ranged from 18 to 70 years, and 60% to 100% was male. Participants were recruited from prosthetic centers, amputee patient groups, hospitals, medical services for armed forces service members, and registered charities (Table 1).[1,3–5,77–83] One of the contacted authors responded to our request for additional data on transtibial amputee patients.[84]

Table 1.

Summary of participant characteristics from studies analyzing factors influencing patient satisfaction with transtibial prosthesis.

Quality criteria that were met for ranging from 6 out of 10 to 10 out of 10 (Table 2). The longitudinal studies [79,84] met 2 and 3 of the 8 additional Minors criteria (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study quality assessment.

3.3. Overall satisfaction

Overall satisfaction with the prosthesis was analyzed in 5 studies.[3,77,78,82,84] Van de Weg and van der Windt[78] compared 2 overall satisfaction scores between groups of patients with different types of liners and found no significant differences between these patients.

A regression analysis demonstrated that male gender, paid work, a nonvascular reason for amputation, and a longer period of time since amputation were associated with somewhat higher satisfaction scores. Ali et al[77] analyzed satisfaction with liners and found significantly higher overall satisfaction scores for Seal-in liner users. Berke et al [3] reported mean overall satisfaction scores (range 0–10) in veterans and service members who lost limbs in the Vietnam conflict (7.3) or in the Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) conflicts (7.5). Harness and Pinzur [82] found overall satisfaction to be associated with “appearance” (r = 0.44), “residual limb health” (r = 0.44), “less pain” (r = 0.40), “ability to ambulate” (r = 0.66), and “ability to make transfers” (r = 0.36). Giesberts et al [84] analyzed satisfaction with the modular socket system in a longitudinal study using an overall prosthesis evaluation score, ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 equaling “not at all satisfied” and 10 equaling “very satisfied.”

Mean visual analogue scale (VAS) scores (range 0–10) for overall satisfaction ranged from 6.9 [77] to 7.7,[84] and mean overall satisfaction sum scores (range 0–21) ranged from 11.0 to 12.0.[78] Mean overall satisfaction with liners (range 0–100) ranged from 63.1 for polyethylene liners to 83.1 for Seal-in liners.[77]

3.4. Appearance

Several studies described the percentage of patients satisfied with the appearance of their prostheses or reported satisfaction scores regarding appearance.[4,77,78,82,84] Harness and Pinzur [82] found a positive association between overall satisfaction and appearance of the prosthesis (r = 0.44). Two studies compared different prosthesis liners in relation to satisfaction with appearance. [77,78] Van de Weg and van der Windt[78] found no significant differences regarding satisfaction with appearance of the prosthesis (“looks”) between users of different liners. Ali et al[77] found that patient satisfaction with appearance of the prosthesis was highest for Seal-in liner users. The operationalization of satisfaction with appearance of the prosthesis included the factors “appearance,” “color,” “touch/feel,” “look (s),” “cosmetics,” and “shape.”[4,77,78,82–84] Giesberts et al[84] found no change in satisfaction with appearance over time using the PEQ, in patients using the modular socket system.

The PEQ was applied in 3 studies and uses an appearance scale to assess satisfaction.[1,82,84] This scale includes 5 questions: 1 on appearance of the prosthesis, 2 on damage done to clothing or prosthesis cover, and 2 on freedom in choice of clothing and shoes. PEQ-based questionnaires were used in 2 studies. One study included a question on cosmetic satisfaction with the prosthesis, a concept closely related to appearance, while the other study included a question on satisfaction with appearance.[77,78] The TAPES, used in 2 studies, includes 1 question regarding satisfaction with appearance.[79,80] This question is part of its Aesthetic Satisfaction Subscale. The other 2 questions of this subscale assess satisfaction with the shape and color of the prosthesis. In the Survey for Prosthetic Use (SPU), used in 2 studies, appearance is not assessed.[3,5] The Satisfaction with Prosthesis Questionnaire (SATPRO) was used in 1 study and includes 15 questions, 1 of which assesses satisfaction with the look of the prosthesis.[81] Two studies used author-designed questionnaires. Dillingham et al[4] used 1 question to assess satisfaction with the appearance of the prosthesis. Cairns et al[83] included a subscale on the aesthetics of the prosthesis, another concept closely related to appearance. This subscale includes 3 questions assessing “color,” “shape,” and “feel/touch” of the prosthesis.

3.5. Properties of the prosthesis

Satisfaction with properties of the prosthesis was reported in 7 studies.[3–5,79,80,83,84] Sinha et al[80] found that satisfaction with the weight of the prosthesis was significantly higher in transtibial amputee patients than in transfemoral amputee patients. Webster et al[79] found significantly lower levels of functional satisfaction in transtibial amputee patients than in transmetatarsal amputee patients. No significant differences in satisfaction with functional and physical properties of the prosthesis were found between Vietnam veterans and OIF or OEF veterans in the study of Berke et al.[3] Another study found a prosthesis rejection rate of 18% in Vietnam veterans and 31% in OIF or OEF veterans.[5] The operationalization of satisfaction with functional and physical properties of the prosthesis included the factors “weight,” “smell,” “noise,” “being waterproof,” “durability,” “reliability,” “usefulness,” “easy to clean,” “ease of use,” “works well regardless of the weather”, “limitations imposed on clothing,” “shoe choice (height and style),” “damage done to clothing,” and “interaction of prosthesis cover with clothing and joint movement.” [3–5,79,80,83,84]

Giesberts et al[84] found a nonsignificant decline in PEQ scores over time when assessing satisfaction with sounds of the prosthesis. The PEQ includes 2 questions on satisfaction with properties of the prosthesis.[1,82] These questions assess the patients’ rating of “prosthesis weight” and “squeaking, clicking or belching sounds” made by the prosthesis. Two PEQ- based questionnaires also included satisfaction questions assessing the properties “sound” and “smell” of the prosthesis.[77,78] The Functional Satisfaction Subscale of the TAPES includes 3 questions on satisfaction with “weight,” “usefulness,” and “reliability” of the prosthesis.[79,80] The SPU has a satisfaction section with 3 questions on satisfaction with “smell,” “sound,” and “weight” of the prosthesis and a dissatisfaction section with questions on “lack of reliability” and “lack of functionality” of the prosthesis.[3,5] In the SATPRO, 4 of the 15 questions concern properties of the prosthesis. The scores on these questions are not analyzed on item level.[81] An author-designed questionnaire included 3 questions on factors affecting satisfaction with the cosmetic properties of prosthesis: “durability,” “being waterproof,” and “easy to clean.” [83]

3.6. Fit

Dillingham et al[4] reported on satisfaction with the fit and comfort of the prosthesis without using a between-group comparison. Other studies that examined the fit of the prosthesis did perform between-group comparisons of war veterans and included the variables employment, gender, marital status, reasons for amputation, years since amputation, and mobility level. Three of 4 studies found no significant differences between groups.[3,78,81] Ali et al[77] found that the type of liner significantly influenced patient satisfaction with the fit of the prosthesis. Satisfaction with prosthesis fit and suspension was highest in Seal-in liner users, and satisfaction with prosthesis donning and doffing was highest in users of polyethylene foam liners.[77] The operationalization of satisfaction with fit included the factors “comfort,” “fit”, “donning and doffing,” “suspension,” “pistoning,” “rotation,” and “socket fit.” [3,4,77,78,81,84]

Giesberts et al[84] found a significant decline (P = .027) in satisfaction with comfort and pain over time using the Socket Fit Comfort Score (SCS) in patients using the modular socket system. The Utility Scale of the PEQ includes 2 questions on satisfaction with the fit and comfort of the prosthesis; the latter is a concept closely related to fit.[1,82] In a PEQ-based questionnaire, 1 question was used to measure satisfaction with fit (“comfort to wear”).[78] The TAPES has incorporated “fit” and “comfort” into 3 questions on prosthesis properties in a subscale assessing satisfaction.[79,80] The SPU includes 1 satisfaction question on “fit.” [3,5] The SATPRO also includes 1 question on satisfaction with the comfort of the prosthesis.[81] The SCS assesses satisfaction with socket comfort while sitting, standing and walking, using a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 being “most uncomfortable socket you can imagine” to 10 the “most comfortable socket fit.”[84]

3.7. Aspects of the residual limb

Berke et al[3] compared differences in satisfaction with the prosthesis between 3 groups of veterans with limb loss. It was found that Vietnam veterans had significantly less skin problems of the residual limb than OIF or OEF veterans, which positively affected their satisfaction with the prosthesis. Another study found overall satisfaction to be associated with residual limb health and less pain in the residual limb (r = 0.4).[82] Giesberts et al[84] found a nonsignificant decline in residual limb health using the PEQ in patients using the modular socket system. The operationalization of satisfaction with the residual limb included the factors “sweating/perspiration,” “wounds,” “irritation,” “blisters,” “pimples,” “skin rash,” “swelling,” “pain,” and “phantom pain.” [1,3–5,79,80,82]

The PEQ includes a Residual Limb Health Scale containing 6 questions and a total of 10 questions on pain, 3 of which specifically assess pain in the residual limb.[1,82,84] Questionnaires based on the PEQ included several questions on different aspects of the residual limb that influence satisfaction, such as “sweating,” “wounds,” “irritation,” “smell,” and “pain.” [77,78] The TAPES includes 1 question on residual limb pain.[79,80] The SPU includes 3 questions on aspects of the residual limb that impact satisfaction; these include “pain,” “skin problems,” and “sweating.” [3,5] An author-designed questionnaire included questions on “skin irritation,” “wounds,” “perspiration,” and “pain.” [4]

3.8. Use of the prosthesis

In 2 studies, differences between groups regarding satisfaction with prosthesis use were analyzed.[77,78] Users of polyethylene foam inserts were more satisfied than users of silicon liners or polyurethane liners while sitting or while walking on uneven terrain.[78] Users of Seal-in liners were more satisfied while “sitting,” “walking,” “walking on uneven terrain,” and “walking on stairs” than users of silicone liners with a shuttle lock or polyethylene foam liners.[77] Harness and Pinzur [82] analyzed factors associated with satisfaction with prosthesis use. Satisfaction with use was associated with the “ability to ambulate” and the “ability to transfer.” Giesberts et al[84] found no significant change in ambulation or prosthesis utility over time in patients fitted with the modular socket system. Another study found that satisfaction with walking with the prosthesis was higher in transtibial amputee patients than in transfemoral amputee patients.[1] The operationalization of satisfaction with use included satisfaction with “sitting,” “walking,” “walking on uneven terrain,” “walking up and down stairs,” “ease of use,” “daily use,” and performance-based measures.[1,4,77,78,82–84]

The Ambulation Scale of the PEQ includes 8 questions, 1 of which assesses satisfaction while walking down the stairs.[1,82,84] The PEQ-based questionnaires included questions on satisfaction with prosthesis use in different circumstances, including “sitting,” “walking,” “climbing stairs,” and “walking on uneven terrain.” [77,78] In the SATPRO, 2 of the 15 questions assess satisfaction with prosthesis use.[81]An author-designed questionnaire assessed satisfaction with a question on “hours of prosthesis use.” [4]

4. Discussion

4.1. Study aim

The analysis of the included studies revealed that a considerable number of transtibial amputee patients were not satisfied with their prostheses or aspects of their prostheses. Satisfaction with the prosthesis is a multidimensional construct that is affected by various factors. In the included studies, several factors were found to influence satisfaction and dissatisfaction and the use of different operationalizations of satisfaction in the questionnaires makes comparison of outcomes between studies impossible.

4.2. Participants

Participants assessed in the included studies were predominantly physically active males who had undergone a traumatic amputation and who had a wide range in age and time since amputation.[1,3–5,77–84] In some studies, participant characteristics were correlated. Armed forces service members, for example, were almost exclusively 30- to- 60-year-old males who were employed, had undergone traumatic amputations, and used their prostheses many hours per day.[3,4] Female amputee patients were underrepresented and outcome regarding appearance, comfort, and use of the prosthesis was not given separately for women.[1,3–5,78,80–84]

4.3. Overall satisfaction

Five studies assessed overall satisfaction with the prosthesis, which is the least specific evaluation of satisfaction.[3,77,78,82,84] Overall satisfaction scores give no insight into the specific aspects of satisfaction and offer no directions for improvement. The operationalization of overall satisfaction was associated with “appearance of the prosthesis” “residual limb health,” “experiencing less pain,” and “being able to ambulate and make transfers.” [3,77,78,82] The scores on overall satisfaction suggest that there is considerable room for improvement (Table 3).

Table 3.

Satisfaction scores and factors related to satisfaction grouped in 5 domains.

4.4. Appearance of the prosthesis

The use of the words “appearance,” “look (s),” “cosmetics,” and “aesthetics” in the questionnaires refer to the operationalization of appearance of the prosthesis and illustrates why it is difficult to draw comparisons between study outcomes. These words are similar in nature, for they all refer to the outward form/appearance of the prosthesis, but subtle semantic differences are nevertheless present. “Appearance” is the more neutral option, whereas “looks” and “aesthetics” refer to the appreciation of the appearance of the prosthesis. “Cosmetics,” in turn, can also refer to the enhancement of the (normal) appearance. These words are not interchangeable, and differences in meaning may result in different interpretations of questions regarding appearance, thereby influencing the outcomes of the questionnaires.

The difference in the number of questions used in the scales of the questionnaires also makes it difficult to compare outcomes. The number of questions on satisfaction with appearance, for example, varied from 1 question in the SATPRO, 3 questions in the TAPES, and 5 questions in the PEQ, all with different scale ranges (Table 4 ). In addition, while most questionnaires assess satisfaction, only 1 assesses dissatisfaction with “reliability” and “functionality” of the prosthesis (SPU).[81] The low satisfaction scores on appearance of the prosthesis indicate that there is also room for (considerable) improvement (Table 3).

Table 4.

Assessment of satisfaction questions in questionnaires.

Table 4 (Continued).

Assessment of satisfaction questions in questionnaires.

Table 4 (Continued).

Assessment of satisfaction questions in questionnaires.

4.5. Properties of the prosthesis

One study reported on rejection rates of the prosthesis of 18% of Vietnam veterans and 31% of OIF/OEF veterans, predominantly because of dissatisfaction with properties of the prosthesis.[5] One study reported an increase of satisfaction with appearance and a decrease in satisfaction with sounds and utility of the prosthesis and a decrease of residual limb health over time.[84] In another study, the mean satisfaction score regarding weight of the prosthesis was 58.1 (range 0–100).[4] Amputee patients with a more proximal amputation were less satisfied with the function and weight of the prosthesis than amputee patients with a more distal amputation, and transfemoral amputee patients were less satisfied while walking with the prosthesis than transtibial amputee patients.[1,79,81] As mentioned above, satisfaction in the domains “residual limb health” and “prosthesis use” is related to overall satisfaction.[82]

Again, considerable improvement is possible in these domains.

4.6. Prosthesis use

The PEQ assesses prosthesis use in different circumstances because of their possible influence on satisfaction. A person might be perfectly satisfied with the prosthesis while sitting but dissatisfied with the same prosthesis while walking on uneven terrain.[1,82] Thus, satisfaction is also related to the kind of activity a person wants to do. Although most questionnaires include questions on prosthesis use, for instance regarding the distance walked, they do not include questions that measure the level of satisfaction with this particular distance.

4.7. Questionnaires

The reviewed studies used existing questionnaires, parts of existing questionnaires, adapted questionnaires, and author-designed questionnaires to measure prosthesis satisfaction. Various operationalizations were used in the questionnaires to assess aspects of satisfaction with a transtibial prosthesis. The reasons for choosing a particular operationalization were not explained in the questionnaire guidelines or discussed in the studies (Table 4 ). Furthermore, it was sometimes difficult to determine whether the questions assessed satisfaction or another construct. The following question illustrates this difficulty: “Over the past four weeks, rate how you felt about being able to walk down stairs when using your prosthesis.” Answering possibilities were on a VAS anchored by “cannot” and “no problem” (PEQ 13D).[1,82] Because the answer indicates the patient's subjective/emotional evaluation of walking, this was considered to be a satisfaction question concerning prosthesis use.

All factors that influence satisfaction were categorized into 5 different domains: appearance, properties, fit, residual limb, and use. The residual limb was mentioned in only 3 studies, despite the fact that it affects satisfaction with the prosthesis. Comparison of study outcomes was difficult due to different operationalizations of satisfaction in the questionnaires, differences in the phrasing of questions and choice of words, and differences in study objectives (Tables 3 and 4). In addition, the time frame studied also influences outcomes and was only evaluated in the PEQ (Table 4 ).

4.8. Prosthesis satisfaction

The findings of this review indicate that it is important for researchers studying prosthesis satisfaction to motivate the use of a specific operationalization and preferably cover all factors and domains influencing satisfaction (Table 4 ). This review provides an overview of factors that affect prosthesis satisfaction and can help researchers assess satisfaction during history taking, clinical examination, and prosthesis evaluation. At the same time, satisfaction is a subjective/emotional evaluation influenced by psychosocial factors that might change and vary over time. To enable research synthesis of prosthesis satisfaction in meta-analyses, researchers should be aware of the different operationalizations used in the questionnaires, for these impede comparisons of outcomes and calculation of effect sizes across studies.

4.9. Limitations of this review

The review was limited by the quality of the studies identified for inclusion. Many studies were excluded because they lacked specific data on transtibial amputee patients. In addition, only 1 author answered our request for additional data. We also excluded studies because of language restrictions and retrieval problems, thereby possibly excluding potential relevant studies. Studies included mainly employed males with traumatic amputations, which limits generalizability of findings to amputee patients with other characteristics. Patients were recruited from specific sources, which also limited generalizability. Finally, the diversity in questionnaires used and the different operationalizations of prosthesis satisfaction made pooling of quantitative data in a meta-analysis impossible.

4.10. Implications for future research

Ideally, prosthesis satisfaction should be systematically evaluated by means of an assessment of all known factors influencing satisfaction. The choice of a specific operationalization and questionnaire should be motivated. Furthermore, future research should take into account that prosthesis satisfaction is an emotional evaluation that is best assessed during a specific time frame, thereby respecting the dynamic aspects of satisfaction. Adhering to these principles will enhance comparability of future studies assessing prosthesis satisfaction and make meta-analysis and pooling of data possible.

5. Conclusion

Factors influencing patient satisfaction with a transtibial prosthesis are diverse and include appearance and properties (functional and physical) of the prosthesis, fit of the prosthesis, functional use of the prosthesis, and aspects of the residual limb. Relevance of certain factors seems to be related to specific amputee groups. Questionnaires assessing patient satisfaction use different operationalizations, making comparisons between outcomes of questionnaires impossible.

Author contributions

Writing – original draft: Erwin Baars, Ernst Schrier, Pieter Dijkstra, Jan Geertzen.

Writing – review & editing: Erwin Baars.

Methodology: Pieter Dijkstra.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: OEF= Operation Enduring Freedom, OIF= Operation Iraqi Freedom, PEQ= Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire, SATPRO= Satisfaction with Prosthesis Questionnaire, SCS= Socket Fit Comfort Score, SPU= Survey for Prosthetic Use, TAPES= Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales, VAS= visual analogue scale.

ECB and ES contributed equally to this work.

Funding/support: No funding was provided. The authors received no financial benefits in relation to this study.

The material in our study has not been previously published or presented.

The author (s) of this work have nothing to disclose.

There is no conflict of interest regarding the manuscript.

References

- [1].Kark L, Simmons A. Patient satisfaction following lower-limb amputation: the role of gait deviation. Prosthet Orthot Int 2011;35:225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].MohdHawari N, Jawaid M, MdTahir P, et al. Case study: survey of patient satisfaction with prosthesis quality and design among below-knee prosthetic leg socket users. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2017;10:868–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Berke GM, Fergason J, Milani JR, et al. Comparison of satisfaction with current prosthetic care in veterans and service members from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts with major traumatic limb loss. J Rehabil Res Dev 2010;47:361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ, et al. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic devices among persons with trauma-related amputations: a long-term outcome study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001;80:563–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gailey R, McFarland LV, Cooper RA, et al. Unilateral lower-limb loss: prosthetic device use and functional outcomes in servicemembers from Vietnam war and OIF/OEF conflicts. J Rehabil Res Dev 2010;47:317–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, et al. Conceptualisation of patient satisfaction: a systematic narrative literature review. Perspect Public Health 2015;135:243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health 2017;137:89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hills R, Dip TP, Kitchen S. Toward a theory of patient satisfaction with physiotherapy: exploring the concept of satisfaction. Physiother Theory and Pract 2007;23:243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gallagher P, Franchignoni F, Giordano A, et al. Trinity amputation and prosthesis experience scales: a psychometric assessment using classical test theory and rasch analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2010;89:487–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gallagher P, MacLachlan M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales (TAPES). Rehabil Psychol 2000;45:130–54. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Richardson A, Dillon MP. User experience of transtibial prosthetic liners: a systematic review. Prosthet Orthot Int 2016;1:6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gholizadeh H, Abu Osman NA, Eshraghi A, et al. Evaluation of new suspension system for limb prosthetics. Biomed Eng Online 2014;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gholizadeh H, Abu Osman NA, Eshraghi A, et al. The effects of suction and pin/lock suspension systems on transtibial amputees’ gait performance. PLos One 2014;9:e945201-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med 2015;8:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 2003;73:712–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Alaranta H, Lempinen VM, Haavisto E, et al. Subjective benefits of energy storing prostheses. Prosthet Orthot Int 1994;18:92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Åström I, Stenström A. Effect on gait and socket comfort in unilateral trans-tibial amputees after exchange to a polyurethane concept. Prosthet Orthot Int 2004;28:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Boutwell E, Stine R, Hansen A, et al. Effect of prosthetic gel liner thickness on gait biomechanics and pressure distribution within the transtibial socket. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012;49:227–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Datta D, Harris I, Heller B, et al. Gait, cost and time implications for changing from PTB to ICEX sockets. Prosthet Orthot Int 2004;28:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Datta D, Vaidya SK, Howitt J, et al. Outcome of fitting an ICEROSS prosthesis: views of trans-tibial amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int 1996;20:111–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dudkiewicz I, Pisarenko B, Herman A, et al. Satisfaction rates amongst elderly amputees provided with a static prosthetic foot. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:1963–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Arwert HJ, Van Doorn-Loogman MH, Koning J, et al. Residual-limb quality and functional mobility 1 year after transtibial amputation caused by vascular insufficiency. J Rehabil Res Dev 2007;44:717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Atherton R, Robertson N. Psychological adjustment to lower limb amputation amongst prosthesis users. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:1201–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chadderton HC. Consumer concerns in prosthetics. Prosthet Orthot Int 1983;7:15–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chen MC, Lee SS, Hsieh YL, et al. Influencing factors of outcome after lower-limb amputation: a five-year review in a plastic surgical department. Ann Plast Surg 2008;61:314–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Coffey L, Gallagher P, Desmond D. A prospective study of the importance of life goal characteristics and goal adjustment capacities in longer term psychosocial adjustment to lower limb amputation. Clin Rehabil 2014;28:196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dajpratham P, Tantiniramai S, Lukkapichonchut P, et al. Factors associated with vocational reintegration among the Thai lower limb amputees. J Med Assoc Thailand 2008;91:234–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Deans SA, McFadyen AK, Rowe PJ. Physical activity and quality of life: a study of a lower-limb amputee population. Prosthet Orthot Int 2008;32:186–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gallagher P, Maclachlan M. Evaluating a written emotional disclosure homework intervention for lower-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83:1464–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gauthier-Gagnon C, Grise M, Potvin D. Enabling factors related to prosthetic use by people with transtibial and transfemoral amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;80:706–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kegel B, Carpenter ML, Burgess EM. A survey of lower-limb amputees: prostheses, phantom sensations, and psychosocial aspects. Bull Prosthet Res 1977;10:43–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, et al. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:931–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sapp L, Little CE. Functional outcomes in a lower limb amputee population. Prosthet Orthot Int 1995;19:92–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Van der Linde H, Hofstad CJ, Geertzen JH, et al. From satisfaction to expectation: the patient's perspective in lower limb prosthetic care. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:1049–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Magnusson L, Ramstrand N, Fransson EI, et al. Mobility and satisfaction with lower-limb prosthesis and orthoses among users in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. J Rehabil Med 2014;46:438–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Jarl G, Heinemann AW, Lindner HY, et al. Cross-cultural validity and differential item functioning of the orthotics and prosthetics users’ survey with Swedish and United States users of lower-limb prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:1615–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Raschke SU, Orendurff MS, Mattie JL, et al. Biomechanical characteristics, patient preference and activity level with different prosthetic feet: a randomized double-blind trial with laboratory and community testing. J Biomech 2015;48:146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sinha R, van den Heuvel WJ, Arokiasamy P, et al. Influence of adjustments to amputation and artificial limb on quality of life in patients following lower limb amputation. Int J Rehabil Res 2014;37:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mohd Hawari N, Jawaid M, Md Tahir P, et al. Case study: survey of patient satisfaction with prosthesis quality and design among below-knee prosthetic leg socket users. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2017;12:868–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ali S, Abu Osman NA, Eshraghi A, et al. Interface pressure in transtibial socket during ascent and descent on stairs and its effect on patient satisfaction. Clin Biomech 2013;28:994–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Coleman KL, Boone DA, Laing LS, et al. Quantification of prosthetic outcomes: elastomeric gel liner with locking pin suspension versus polyethylene foam liner with neoprene sleeve suspension. J Rehabil Res Dev 2004;41:591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gholizadeh H, Abu Osman NA, Eshraghi A, et al. Transtibial prosthetic suspension: less pistoning versus easy donning and doffing. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012;49:1321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hachisuka K, Dozono K, Ogata H, et al. Total surface bearing below-knee prosthesis: advantages, disadvantages, and clinical implications. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:783–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Selles RW, Janssens PJ, Jongenengel CD, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing functional outcome and cost efficiency of a total surface-bearing socket versus a conventional patellar tendon-bearing socket in transtibial amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Eshraghi A, Abu Osman NA, Karimi MT, et al. Quantitative and qualitative comparison of a new prosthetic suspension system with two existing suspension systems for lower limb amputees. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2012;91:1028–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Horne CE, Neil JA. Quality of life in patients with prosthetic legs: a comparison study. JPO 2009;21:154–9. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Boldingh EJ, Van Pijkeren T, Wijkmans DW. A study on the value of the modified KBM prosthesis compared with other types of prosthesis. Prosthet Orthot Int 1985;9:79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ali A, Abu Osman NA, Abd Razak NA, et al. The effect of dermo and Seal-in X5 prosthetic liners on pressure distributions and reported satisfaction during ramp ambulation in persons with transtibial limb loss. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2015;159:31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Morgan SJ, McDonald CL, Halsne EG, et al. Laboratory- and community-based health outcomes in people with transtibial amputation using crossover and energy-storing prosthetic feet: a randomized crossover trial. PLoS One 2018;13:e0189652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Desmond D, Gallagher P, Henderson-Slater D, et al. Pain and psychosocial adjustment to lower limb amputation amongst prosthesis users. Prosthet Orthot Int 2008;32:244–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gunawardena NS, Seneviratne RA, Athauda T. Prosthetic outcome of unilateral lower limb amputee soldiers in two districts of Sri Lanka. JPO 2004;16:123–9. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Akarsu S, Tekin L, Safaz I, et al. Quality of life and functionality after lower limb amputations: comparison between uni- vs. bilateral amputee patients. Prosthet Orthot Int 2013;37:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Coffey L, Gallagher P, Horgan O, et al. Psychosocial adjustment to diabetes-related lower limb amputation. Diabet Med 2009;26:1063–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bilodeau S, Hebert R, Desrosiers J. Lower limb prosthesis utilization by elderly amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int 2000;24:126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Murray C, Fox J. Body image and prosthesis satisfaction in the lower limb amputee. Disabil Rehabil 2002;24:925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Karmarkar AM, Collins DM, Wichman T, et al. Prosthesis and wheelchair use in veterans with lower-limb amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009;46:567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Legro MW, Reiber G, Del Aguila MD, et al. Issues of importance reported by persons with lower limb amputations and prostheses. J Rehabil Res Dev 1999;36:155–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Zidarov D, Swaine B, Gauthier-Gagnon C. Quality of life of persons with lower-limb amputation during rehabilitation and at 3-month follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90:634–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Fisher K, Hanspal R. Body image and patients with amputations: does the prosthesis maintain the balance? Int J Rehabil Res 1998;21:355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Matsen SL, Malchow D, Matsen FA. Correlations with patients’ perspectives of the result of lower-extremity amputation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000;82-A:1089–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Pezzin LE, Dillingham TR, Mackenzie EJ, et al. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic limb devices and related services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:723–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Roth EV, Pezzin LE, McGinley EL, et al. Prosthesis use and satisfaction among persons with dysvascular lower limb amputations across postacute care discharge settings. PM R 2014;6:1128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Buijk CA. Use and usefulness of lower limb prostheses. Int J Rehabil Res 1988;11:361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Christ O, Jokisch M, Preller J, et al. User-centered prosthetic development: comprehension of amputees’ needs. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2012;2012:1929–32.23366292 [Google Scholar]

- [65].Gallagher P, Maclachlan M. Adjustment to an artificial limb: a qualitative perspective. J Health Psychol 2001;6:85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Durmus D, Safaz I, Adigüzel E, et al. The relationship between prosthesis use, phantom pain and psychiatric symptoms in male traumatic limb amputees. Compr Psychiatry 2015;59:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Moustapha A, Sagawa Junior Y, Watelain E, et al. Epidemiological cross-sectional survey of outcome in lower-limb amputees in the Nord-Pas de Calais region. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2010;53:e22. [Google Scholar]

- [68].Safari MR, Tafti N, Aminian G. Socket interface pressure and amputee reported outcomes for comfortable and uncomfortable conditions of patellar tendon bearing socket: a pilot study. Assist Technol 2015;27:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kuret Z, Burger H. Quality of life in lower limb amputees. Prosth Orthot Int 2015;39: suppl 1 (434). [Google Scholar]

- [70].Magnosson L. Variables associated with patients’ satisfaction with low cost technology prosthetic and orthotic devices and service delivery in Malawi and Sierra Leone. Prosth Orthot Int 2015;39: suppl 1 (76). [Google Scholar]

- [71].Posada AM, Lugo LH, Plata JA, et al. Patients’ perspectives on lower limb amputation outcomes. Prosth Orthot Int 2015;39: suppl 1 (230). [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kangkasomboon T, Assarut N, Sakaew T, et al. Self-image and attitude on prosthetic cosmetic cover in lower limb amputee in Thailand. Prosth Orthot Int 2015;39Suppl 1:549–50. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Vazvani HG, Yahyavi E, Eshraghi A, et al. Clinical assessment of a new prosthetic suspension system. Prosth Orthot Int 2015;39: [Epub ahead of print]. [Google Scholar]

- [74].Vance RL, Gallagher P, O’Keeffe F, et al. The impact of cognition on physical and psychosocial outcomes at discharge from a lower limb prosthetic rehabilitation programme. Prosth Orthot Int 2015;39: suppl 1 (545). [Google Scholar]

- [75].Migaou Miled H, Ben Brahim H, HadjHassine Y, et al. Tunisian lower limb amputees and satisfaction towards their prosthesis: about 74 cases. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2016;59S:e31–2. [Google Scholar]

- [76].Christ O, Beckerle P, Rinderknecht S, et al. Usability, satisfaction and appearance while using lower limb prostheses: implications for the future. Neurosci Lett 2011;500:e50. [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ali S, Abu Osman NA, Naqshbandi MM, et al. Qualitative study of prosthetic suspension systems on transtibial amputees’ satisfaction and perceived problems with their prosthetic devices. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:1919–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].van de Weg FB, van der Windt DAWM. A questionnaire survey of the effect of different interface types on patient satisfaction and perceived problems among trans-tibial amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int 2005;29:231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Webster JB, Hakimi KN, Williams RM, et al. Prosthetic fitting, use, and satisfaction following lower-limb amputation: a prospective study. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012;49:1493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Sinha R, van den Heuvel WJ, Arokiasamy P. Adjustments to amputation and an artificial limb in lower limb amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int 2014;38:115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Samitier CB, Guirao L, Costea M, et al. The benefits of using a vacuum-assisted socket system to improve balance and gait in elderly transtibial amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int 2016;40:83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Harness N, Pinzur MS. Health related quality of life in patients with dysvascular transtibial amputation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;383:204–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Cairns N, Murray K, Corney J, et al. Satisfaction with cosmesis and priorities for cosmesis design reported by lower limb amputees in the United Kingdom: instrument development and results. Prosthet Orthot Int 2014;38:467–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Giesberts B, Ennion L, Hjelmstrom O, et al. The modular socket system in a rural setting in Indonesia. Prosthet Orthot Int [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]