Abstract

Biologic aging results in a chronic inflammatory condition, termed inflammaging, which establishes a risk for such age-related diseases as neurocardiovascular diseases; therefore, it is of great importance to develop rejuvenation strategies that are able to attenuate inflammaging as a means of intervention for age-related diseases. A promising rejuvenation factor that is present in young blood has been found that can make aged neurons younger; however, the component in the young blood and its mechanism of action are poorly elucidated. We assessed rejuvenation in naturally aged mice with extracellular vesicles (EVs) or exosomes extracted from young murine serum on the basis of different spectrums of microRNAs in these vesicles from young and old sera. We found that EVs extracted from young donor mouse serum, rather than EVs extracted from old donor mouse serum or non-EV supernatant extracted from young donor mouse serum, were able to attenuate inflammaging in old mice. Inflammaging is attributed to multiple factors, one of which is thymic aging-released self-reactive T cell–induced pathology. We found that the attenuation of inflammaging after treatment with EVs from young serum partially contributed to the rejuvenation of thymic aging, which is characterized by partially reversed thymic involution, enhancement of negative selection signals, and reduced autoreactions in the periphery. Our results provide evidence for understanding of the potential rejuvenation factor in the young donor serum, which holds great promise for the development of novel therapeutics to reduce morbidity and mortality caused by age-related inflammatory diseases.—Wang, W., Wang, L., Ruan, L., Oh, J., Dong, X., Zhuge, Q., Su, D.-M. Extracellular vesicles extracted from young donor serum attenuate inflammaging via partially rejuvenating aged T-cell immunotolerance.

Keywords: young serum, exosomes, rejuvenation, age-related thymic involution, chronic inflammation

INTRODUCTION

When people age, a chronic inflammatory condition is established in the body; it is a risk factor for age-related neurocardiovascular diseases. Therefore, it is of great importance to develop rejuvenating agents as interventions for age-related diseases. In the past decade, the use of young blood to rejuvenate aged neurons in animals led to the development of a promising natural rejuvenation factor; however, the component in the young blood and its mechanism of action are poorly understood. We tested rejuvenation in naturally aged mice with extracellular vesicles (EVs) or exosomes extracted from a pool of young murine serum. We found that EVs extracted from young donor mouse serum, rather than EVs from old donor mouse serum or non-EV supernatant from young mouse serum in which EVs are removed, were able to attenuate chronic inflammation in old mice. This age-related chronic inflammation is attributable to multiple factors, including tissue damage that results from a type of white blood cell, called self-reactive T-lymphoid cells, which are released from the aged thymus gland, an immune system organ. We identified that the attenuation of inflammation after treatment with EVs from young serum partially contributed to the rejuvenation of thymic aging, such as in the enhancement of thymic negative selection signals, which are able to kill self-reactive T-lymphoid cells to establish healthy self-recognition. Our results provide evidence for understanding the potential rejuvenation factor in young serum, which holds great promise for the development of novel therapeutics to reduce morbidity and mortality as a result of age-related inflammatory diseases.Compelling evidence shows that aging of certain systems can be rejuvenated by providing aged mice with young mouse blood through a heterochronic parabiosis model in which the circulatory systems of young and aged mice are surgically joined (1–9), or through infusion of young donor serum/plasma into aged animals (1). A mysterious blood-borne rejuvenation factor that exists in young donor serum/plasma has been proposed; however, whether the whole young serum or some components in the young serum caused the rejuvenation effect is unknown. If the components are responsible, the identity of this hypothesized rejuvenation factor is also largely unknown. In the past decades, many potential rejuvenation factors have been tested. It could be the circulating chemokine CCL11 that promoted neurogenesis and improved declined cognition in aged mice (8). It may also be a growth factor, as several years ago a growth protein, TGF-β superfamily member growth differentiation factor 11 (GDF11), was found to have the rejuvenation function in aged neurons and myocardium (6, 7, 10); however, the role of GDF11 in skeletal muscle regeneration was later challenged (11, 12). In addition, the effect of the rejuvenation factor in the rejuvenation of the aged immune system remains unclear, as this effect was assessed to be uncertain (3) or inefficient (13) in a heterochronic parabiosis model, and the effect on immune system rejuvenation via infusion of young donor serum/plasma into aged animals has never been tested.

We believe that there must be multiple factors involved, such as some classic secreted factors—cytokines and chemokines, growth factors, angiogenic factors, and other circulating immune system components; however, changes in the expression of these factors can be regulated by genetic and epigenetic regulators in the postnatal life. Therefore, we hypothesize that one of the rejuvenation factors should be extracellular vesicles (EVs) in young donor serum, mostly exosomes (14, 15), in which there are a large number of microRNAs (miRNAs) and other epigenetic factors able to induce changes—expression and/or repression—in all the components mentioned above. In brief, exosomes are a kind of EV, formed in endosomal compartments of all types of secreting cells. Exosomes contain a large number of soluble components, such as lipids, proteins, and RNAs (mainly miRNAs) (16–18). In particular, serum exosomes contain high concentrations of miRNAs (19). Exosomes act as cargo carriers to transport these epigenetic factors to signal between cells (20, 21). miRNAs in exosomes are potential factors that conduct the regulation of post-transcription by targeting the 3′-UTR of a gene, thereby regulating transcriptional expression and repression for immune cell activation and senescence (22–24), which is associated with age-related inflammatory diseases (25, 26). Therefore, post-transcriptional regulation of most events during the aging process can be achieved by exosomes (21, 27, 28). Serum-extracted EVs also contain other factors, such as microvesicles, ectosomes, etc. (15). These are all membrane-comprised vesicles with different sizes and densities that are involved in the transportation of regulator factors to regulate immune responses (29).

Inflammaging is characterized by low-grade, but above baseline, and sustained chronic inflammation associated with aging (30–34). Although the etiology is not fully understood (35), inflammaging has been attributed to a mixture of multiple factors, including cellular senescence-induced senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) from somatic cells (33, 36) that release low levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1, and C-reactive protein (33, 36–38), as well as the persistent activation of immune cells by chronic viral infections, such as cytomegalovirus—so-called foreign-reactive immune cells (32, 34, 39–41). Furthermore, we found that aged thymus-released auto(self)-reactive T cells, which attack structural tissues to induce persistent self-tissue damage, also contribute to the emergence of a chronic inflammatory state with advanced age (42, 43). Age-related thymic involution, a natural phenomenon of the aging process, results in not only an insufficient output of naive T cells, which is one cause of immunosenescence, but also an enhanced release of harmful self-reactive T cells, another important source of chronic inflammation (44). For example, these self-reactive T cells potentially attack the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which results in increased permeability and reduced selectivity of the BBB (45, 46), thereby progressively facilitating the invasion of the CNS by a variety of inflammatory cells (46).

In the current study, we tested the rejuvenation effect on naturally aged mice with a potential rejuvenation factor, namely, EVs that were extracted from young murine serum (labeled Young-EVs in figures), with an average diameter of ∼100 nm (comprising mostly exosomes and ectosomes: 50–100 and 50–200 nm in diameter, respectively) (29), isolated from a pool of young mice using the ExoQuick reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). We found that EVs from young donor serum were able to attenuate serum IL-6 (a proinflammatory factor) levels in naturally aged mice, whereas EVs extracted from aged murine serum (labeled Aged-EVs in figures) and young donor murine serum supernatant (labeled Young non-EV in figures; from the young serum after EVs were removed) were not able to do so. The decline of inflammaging was associated with the aged T-cell immune system both in the periphery and the CNS of old mice, which was potentially attributable to the rejuvenation of thymic aging and partially attributable to the enhancement of Nur77 and CD5 signals in thymocyte negative selection, thereby potentially improving the function of negative selection and central tolerance generation. Our results provide a clue related to the potential rejuvenation factor’s identity and mechanism in young serum, which holds great promise for the development of novel therapeutics to reduce morbidity and mortality caused by age-related diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, animal care, and adoptive transfer

Young (2–3 mo) and aged (18–20 mo) mice with the C57BL/6 genetic background were used for experiments with retro-orbital injection of EVs extracted from mouse serum, vehicle PBS, or non-EV supernatant from young serum (after removing EVs). Tissue samples from mice with the various treatments were freshly isolated at the end point. Aged mice were provided by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Aging aged rodent colony. For adoptive transfer of lymphocytes to observe the improvement of autoimmune phenotypes, erythrocyte-depleted spleen cells from aged wild-type donor mice that were treated with either PBS or EVs from young serum were intravenously injected via the retro-orbital route into young Rag−/− recipient mice (2.0 × 107 cells per recipient mouse). Eight weeks after injection, salivary glands from Rag−/− recipient mice were collected for analysis of inflammatory cell infiltration. All animal experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of North Texas Health Science Center in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Preparation and characterization of EVs from freshly isolated murine sera and intravenous injection into aged mice

Murine sera from a pool of ∼30 young or old mice per extraction, collected by cardiac puncture at the time of euthanasia and isolated with centrifugation, were filtered with or without a 0.2-μm filter, followed by extraction with the ExoQuick reagent (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Precipitated EVs were resuspended with sterile PBS at a volume equal to one half of the original serum sample, whereas non-EV serum supernatant was maintained at approximately an equal volume of original serum. The characterization of extracted EVs included the measurement of size with 500 μl of prepared EV sample diluted 1:1 in MilliQ water (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) using a Delsa Nano HC Particle Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) at 90° light scattering at 25°C. Extracted EVs were also analyzed for morphologic characterization. EVs from young serum were diluted in PBS 1:100 and 40 μl of the sample was dropped onto a glass coverslip and allowed to gently air dry. An Ntegra Prima (NT-MDT Spectrum Instruments, Moscow, Russia) was used in semicontact mode with NSG10 tips to collect atomic force microscopy images. Images were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) and graphs were made in Origin v.9.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). The prepared EV sample was stored at −80°C until use.

For characterization of miRNA profiles of EVs from young and old mice serum, total RNA was isolated and purified using an miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity (A260/A280 ratio ≥1.8) was confirmed by spectrophotometry. Then, 1–3 μg of total RNAs for each sample were used for customized miRNA microarray service from LC Sciences (Houston, TX, USA). In brief, Cy3-labled samples were hybridized in each chip with probes that detect miRNA transcripts listed in Sanger miRBase Release 21 (University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom). Chips were scanned and images are displayed in pseudocolors so as to expand visual dynamic range. As signal intensity increases from 1 to 65,535, the corresponding color changes from blue to green, to yellow, and to red. miRNA with a signal value >10 U was selected.

Aged mice were intravenously injected via the retro-orbital route with 100 μl of EVs (extracted from 200 μl of original serum), 100 μl of PBS (for control), or non-EV serum supernatant from young serum after removal of EVs (∼200 μl from 200 μl of original serum). Young mice were intravenously injected with 100 μl PBS for control. Eight injections were performed in total, with each injection separated by a 2-d interval for a total of 22 d (1). Two days after the last injection, mice were euthanized for analysis.

ELISA for inflammatory cytokines and antinuclear antibody concentration

Mouse serum (1:2 dilution) IL-6 and IL-1β levels were quantified by ELISA (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. IL-6 and IL-1β standard curves were generated with a range of 0–200 pg/ml. Antinuclear Ab (ANA) concentration in mouse serum (1:50 dilution) was also quantified using an ELISA kit (Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A concentration standard curve was generated with a range 0–1000 U/ml of purified Ig isotypes supplied in the kit. Samples were run in duplicate, and data represent means of multiple animals (indicated in the figures). The substrate was 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm with the BioTek ELx800 ELISA reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

Real-time RT-PCR assays for gene expression

Total RNAs from mouse thymus and spleen were isolated with Trizol reagent and reverse transcribed to cDNA using the SuperScriptIII cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time RT-PCR was performed with TaqMan reagents and primers (FoxN1, ΔNp63, TNF-α, Aire, house keeper GAPDH, and 18sRNA) (47). Relative expression levels of mRNAs from the thymus and spleen were internally normalized to GAPDH and 18sRNA levels, then compared with a ΔΔCt value from pooled young wild-type mice samples, which was always arbitrarily set as 1.0 in each real-time RT-PCR reaction.

Isolation of non-neuronal single cells from the mouse brain and flow cytometric analysis of brain non-neuronal cells

Experiments were performed according to a previously established method, with a few modifications (48, 49). Deeply anesthetized mice underwent cardiac perfusion of 50 ml PBS. Each dissected brain was digested with 1 ml of 1× HBSS that contained 2 mg/ml collagenase D (MilliporeSigma) and 28 U/ml DNase I (MilliporeSigma) for 45 min in a water bath at 37°C. Released cells were isolated by Percoll (MilliporeSigma) gradient centrifugation at 500 g for 20 min. Cells were collected from the 30%/70% Percoll interface. Isolated brain cells were stained with FITC anti-mouse CD45, PE anti-mouse CD11b, PerCP anti-mouse I-A/I-E, and APC anti-mouse CD3ε (all from BioLegend) at 4°C for 20 min protected from light.

Flow cytometric assay for cell surface markers and intracellular molecules

Single-cell suspensions of thymocytes or spleen cells were stained with combinations of fluorochrome-conjugated Abs against cell-surface markers and/or an intracellular marker (IL-2, IFN-γ, or Nur77), indicated in each figure. Data were acquired using a BD LSRII Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining in cryosections

Cryosections (5–6 μm thick) were stained as described previously (50). Primary Abs used were keratin-5 (K5; Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA) and K8 (Troma-1 supernatant); anti-β5t (Medical and Biological Laboratories, Nagoya, Japan) and Biotinylated-UEA-1 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and anti-Aire (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). On the basis of primary Ab species, secondary Abs used were Cy3-conjugated or Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or anti-rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA), or Cy3-conjugated streptavidin. Positive staining areas were analyzed by ImageJ software.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining for checking lymphoinfiltration

Mouse salivary glands from recipient young Rag−/− mice and control mice were fixed, cut into 5-μm-thick sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistics

Comparisons were made by Student’s t test.

RESULTS

Characteristics of serum-extracted EVs

It is likely that young serum makes the aged system younger via changes in epigenetic regulation, rather than simply by supplying nutrition or growth factors. We postulated that these epigenetic regulators are transferred as a pool, encapsulated in serum EVs that transport them to other cells. This would explain how the epigenetic factors are transferred from young to aged individuals without degradation.

We know that serum EVs contain a large number of nucleotide-containing molecules, typically noncoding miRNAs that can act as epigenetic regulators by binding to the 3′-UTR of a gene transcript to alter post-transcriptional gene expression and repression. A combination of multiple miRNAs may balance a group of genes with similar functions. Therefore, we extracted serum EVs from a pool of young mice (∼30 mice in each pool) using the ExoQuick reagent. To identify what we extracted and to obtain consistent results, we confirmed our serum extraction with 2 different approaches: checking particle size with a Delsa Nano HC Particle Analyzer and assessing morphology with an atomic force microscope. For EV size, we found that the diameter of EVs extracted usually fell into an intermediate diameter of 96–117 nm, with and without using a 0.2-μm-filter for pretreatment (Fig. 1A). As for the assessment of EV morphology we extracted (Fig. 1B), it was the same as in a previously published report (51).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of serum-extracted EVs. A) Comparison of the sizes of EVs extracted from young murine serum by the ExoQuick reagent pretreated with and without using 0.2-μm filters. B) Morphology of EVs from young murine serum used in this project for rejuvenation of inflammaging, photographed by atomic force microscopy (AFM). C, D) Different miRNA expression profiles in heatmap (C) and quantified summary (D) of EVs from young vs. old murine serum, analyzed by murine miRNA microarray with Mus musculus miRBase version-21 arrays that contained 1900 unique mature miRNA probes (miRNA microarray service via LC Sciences).

In addition, we checked miRNA profiles of serum EVs extracted from young and aged mice with microarray of Mus musculus miRBase version-21 array chips, where each chip contained 1900 unique mature miRNA probes (miRNA microarray service via LC Sciences). We found that not all of the 1900 mature miRNAs could be detected. In the detected miRNAs (signals are 10–10,000 U), serum EVs from young and old mice demonstrated different miRNA expression profiles (Fig. 1C, D). There were 19 miRNAs with increased expression and 15 with decreased expression in serum-extracted EVs from 3 individual aged mice compared with 3 individual young mice, shown in the heatmap (Fig. 1C). These differences in miRNA expression in EVs between young and aged mice may generate a platform for a potential epigenetic regulation (suppression and/or enhancement) of certain transcription factors, thereby inducing changes in other functional or structural gene expression and potentially rejuvenating aged phenotypes.

EVs extracted from young donor serum reduced age-related chronic inflammation in the periphery

The etiology of inflammaging is potentially attributable to SASP of senescent cells in somatic tissue (33) and self-reactive T cell–induced chronic self-tissue damage (44). Inflammaging is characterized by a low-grade, chronic inflammation, whereas EVs and their miRNA cargo are potential regulators for the attenuation of both chronic inflammation (22) and acute inflammation (52). Therefore, we hypothesized that EVs extracted from young donor serum, predominantly exosomes, which contain a different spectrum of miRNAs from their old counterparts (Fig. 1C, D), could potentially be used as therapies (53) to attenuate inflammaging. We extracted EVs from a pool of young (1–3 mo old) murine serum. To exclude an effect from non-EV components in young serum and EVs from old serum, we preliminarily compared the rejuvenation effect by assessing IL-6 concentration (Fig. 2A, left). We intravenously injected EVs from young serum, aged serum, young non-EV serum supernatant, or PBS (vehicle control) into 18-mo-old (aged) mice for a total of 8 injections per mouse. Each injection dose was extracted from 200 μl of original serum, as detailed in Materials and Methods and based on the published strategy of whole-serum injection (1). We found that EVs extracted from young serum, rather than EVs from aged serum or young non-EVs, were able to reduce the increased IL-6 levels in aged mice (Fig. 2A, left).

Figure 2.

EVs extracted from young serum reduced proinflammatory factors in aged mice. A) Proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 (left) and IL-1β (right), were increased above baseline in aged murine serum, but were significantly decreased after treatment with EVs extracted from young serum (detailed in Materials and Methods) as measured by ELISA; however, changes in IL-6 expression in mice that were treated with EVs from aged serum or young non-EV serum supernatant could not be observed (left, the rightmost 2 striped bars). B) Proinflammatory factor, TNF-α, was increased above baseline in aged murine spleen, but was significantly reduced after treatment with EVs extracted from young serum, as in panel A, measured by real-time RT-PCR. C) Dot plots show a representative flow cytometric gate profile of splenic CD4+IFN-γ+ T cells from aged mice after costimulation with anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 (left). The right panel shows a summarized result of reduction of splenic %CD4+IFN-γ+ T cells from aged mice after treatment with EVs extracted from young serum. P values are shown in each panel.

Our results also demonstrated that EVs extracted from young donor serum were able to reduce other typical proinflammatory factors in the periphery of aged mice, such as IL-1β, which is increased above baseline in the aged murine serum (Fig. 2A, right), and TNF-α, which is increased above baseline in the aged murine spleen (Fig. 2B); these are markers of inflammaging. We assessed the response of T-helper cells to costimulation by anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 and found that splenic CD4+ T cells from aged mice had an increased tendency toward to type-1 T-helper phenotype (CD4+IFN-γ+ T cells), whereas this tendency was corrected to the normal level (∼5% splenic CD4+IFN-γ+ T cells) after treatment with EVs extracted from young donor serum (Fig. 2C). Results imply that EVs extracted from young donor serum have the potential to attenuate chronic inflammation in the periphery of aged individuals (Fig. 2).

EVs extracted from young donor serum also reduced age-related chronic inflammation in the CNS

We asked whether this effect of EVs extracted from young donor serum on the attenuation of inflammaging observed in the aged periphery could also be found in the CNS, because the CNS is more severely affected by inflammaging because of its higher sensitivity and vulnerability. In addition, peripheral chronic inflammation is usually associated with CNS inflammation during aging as a result of an increased permeability of the BBB in the elderly. In particular, we compared changes in the percentages of CD3+ T cells and blood-derived macrophages (Mϕs), which are few in the young brain, but are potentially increased in the aged brain, which is representative of chronic neuronal inflammation. We also observed changes in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression in microglia. Expression of MHC molecules is limited within the CNS parenchyma (54, 55), and its increase is potentially related to the activation of immune cells. These parameters were assayed in brains of young and naturally aged (≥18 mo old) mice after treatment with sterile PBS or EVs extracted from young donor serum.

Although the results (Fig. 3) are based on low cell numbers isolated from brain tissue with PBS perfusion and enzymatic dissociation followed by 30%/70% Percoll density centrifugation isolation and flow cytometric staining (Fig. 3A), they corresponded well with peripheral results (Fig. 2). EVs extracted from young donor serum were able to reduce the inflammaging condition in the CNS of aged mice, which was characterized by a decrease in the percentage of CD3+ cells in CD45+CD11b− population in non-neural cells (Fig. 3B, bottom right, C, left), a decrease of blood-derived Mϕs (CD45highCD11b+ population in non-neural cells), and a decrease of MHC-II expression intensity in microglia (CD45−/lowCD11b+ population; CD45 positive, low, and negative subsets are divided with dotted lines in Fig. 3B, top) residing in the brains of naturally aged mice that were treated with EVs from young serum (Fig. 3C, middle and right). These parameters were all increased in naturally aged mice, as shown in PBS-treated aged mice (control group), as they are typical phenotypic markers of inflammaging (Fig. 3C, opened square symbols). Results suggest that EVs from young serum can either deliver signals into the aged CNS by passing through the BBB or suppress inflammaging in the periphery, which subsequently affects inflammation in the CNS via interaction between the periphery and the CNS.

Figure 3.

EVs extracted from young serum reduced inflammaging in the CNS of aged mice. A) Workflow for isolating non-neural mononuclear cells from brains. B) A representative flow cytometric profile of brain mononuclear cells from young mice and aged mice that were treated with PBS or EVs extracted from young serum (detailed in Materials and Methods). Dot plots in the top row show gates of microglia (CD45−/lowCD11b+ population), Mϕs (CD45highCD11b+ population), and potential lymphocytes (CD45+CD11b− population). Dot plots in the bottom row show gates of CD3+ population from the CD45+CD11b− population in which neural cells were excluded. Two vertical dotted lines in panel B (top) divide CD45 staining into CD45−, CD45low, and CD45high (from left to right) subsets. C) Summarized results of %CD3+ cells in the CD45+CD11b− population (left), %Mϕs in non-neural cells (CD45highCD11b+ population; middle panel), and MHC-II expression strength [mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)] in microglia (CD45−/lowCD11b+ population) of mouse brains from the 3 treatment groups. These 3 parameters, which represent inflammation in the CNS, were increased in aged mice, but decreased after injection with EVs extracted from young serum. P values are shown in each panel, and each symbol represents an individual animal sample.

Meanwhile, we found that impaired neural (spinal cord) regeneration was improved after an injection of EVs from young serum into aged mice with lysolecithin-induced artificial spinal cord injury (4), which demonstrates an enhancement of angiogenesis (Supplemental Fig. 1B, C, top; increased CD34+ cells) and neural regeneration [Supplemental Fig. 1B, C, bottom; increased activation of NKx2-2 (oligodendrocyte precursor) and Ki-67 (proliferation) double-positive cells]. These changes imply that the suppression of neuronal inflammation potentially provides suitable cues from the neuronal microenvironment for neural regeneration.

Parameters of age-related thymic involution were partially improved after treatment with EVs from young serum

As mentioned earlier, aging-induced chronic inflammation is mainly attributed to 2 etiologies, SASP (33) and self-reactive T cell–induced chronic self-tissue damage (44). Here, we have focused on the second etiology, which results from age-related thymic involution; therefore, we asked whether the suppression of inflammaging by EVs from young serum is partially responsible for the rejuvenation of thymic function, thereby reducing the release of self-reactive T cells into the periphery. Accordingly, we observed changes in the thymus.

We found that, after 8 treatments with EVs extracted from young serum, aged thymic mass and total thymocyte numbers were increased (Fig. 4A–C). Although these changes did not mirror those of thymic mass and thymocyte numbers of the young thymus, they were significantly increased compared with the control group with PBS treatment. Therefore, EVs extracted from young serum induced partial rejuvenation in the aged thymus. We also found that expressions—with real-time RT-PCR assay—of FoxN1 and ΔNp63 were significantly increased in the aged thymus after treatment with EVs extracted from young serum (8 treatments; Fig. 4D, E). Results indicate that the postnatal thymic epithelial cell homeostatic regulators in the p63-FoxN1 regulatory axis (50), which are decreased and associated with thymic aging, are improved after treatment with EVs from young serum.

Figure 4.

EVs extracted from young serum induced partial rejuvenation of the aged thymus. A) A representative image of murine thymuses showing the aged involuted thymus (middle) compared with the young thymus with normal size (left) was partially increased in size after treatment with EVs extracted from young serum (right). B) A summarized result shows thymic mass changes with a similar tendency as that in panel A. C) A summarized result shows thymocyte number changes with a similar tendency as those in panels A, B. D, E) Summarized results of FoxN1 (D) and ΔNp63 (E) expression, with a real-time RT-PCR assay, in murine thymuses of young and aged mice that were treated with PBS and EVs extracted from young serum, respectively, with the same tendencies as those in panels A–C. P values are shown in each panel.

Aging-induced abnormal thymic microstructure was improved after infusion with EVs extracted from young serum, which was associated with rejuvenation of the aged thymus

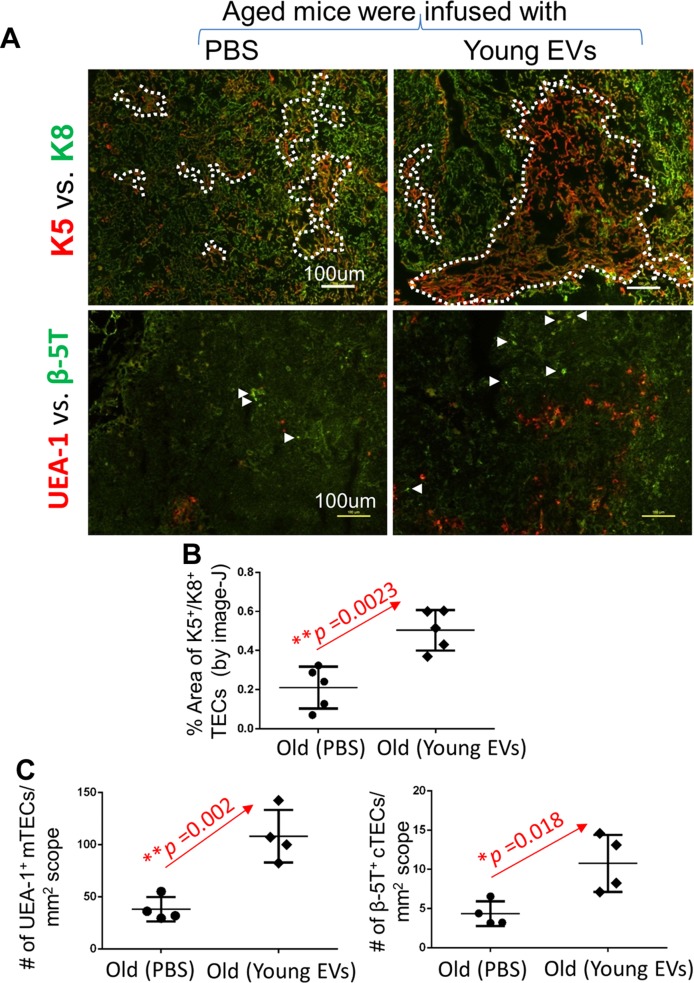

To rejuvenate the involuted, aged thymus to become similar to its young counterpart, a persistent elevation of FoxN1 levels in the aged thymus is likely required, which can be achieved in FoxN1 transgenic models (56, 57); however, our system provides a transient increase of FoxN1 expression, as we administered only 8 injections. This does not allow the aged thymus to rejuvenate to the same level as that of a young thymus. We asked whether EV treatment can leave any visible thymic effects after the termination of the injections; therefore, we assessed changes in thymic microstructure. As we know, in the aged thymus, keratin-5 (K5) –positive medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) demonstrate disconnection, and UEA-1+ mature mTECs and β-5T+ cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) are reduced (Fig. 5A, left). After treatment with EVs extracted from young serum, these age-related abnormal changes in microstructures were partially rejuvenated in the aged thymus. K5+ mTECs were increased (Fig. 5B) and arranged in an organized manner to form connected regions (Fig. 5A, upper right), and UEA-1+ mTECs and β-5T+ cTECs were increased (Fig. 5A, lower right, C). These microstructural changes indicate that even short-term treatment with EVs from young serum can still improve, to some extent, the aged thymic microstructure.

Figure 5.

EVs from young serum induced rejuvenation of age-related abnormal microstructure in the aged thymus. A) Representative thymic cryosections with immunofluorescence staining shows the images of K5 (representing the medulla) vs. K8 (representing the cortex) in the top row, and UEA-1 (representing mature mTECs) vs. β-5T (representing progenitor cTECs) in the bottom row. Thymuses were from aged mice that were treated with PBS (for control) and EVs extracted from young serum. Dotted lines indicate corticomedullary borders, and arrows indicate typical β-5T positive cells. Data are representative of 3 biologic replicates in each group with essentially identical results. B) A summarized semiquantified result of K5+ mTECs vs. K8+ cTECs in thymuses from aged mice that were treated with PBS (for control) and EVs extracted from young serum, respectively. C) Summarized results of UEA-1 (representing mature mTECs) and β-5T (representing progenitor cTECs) in thymuses from aged mice that were treated with PBS (for control) and EVs extracted from young serum, respectively. P values are shown in each panel, each symbol represents 1 scope of thymic tissue under microscope.

Expression of negative selection–associated molecules was elevated in the aged thymus after treatment with EVs extracted from young serum

We asked whether this 8-time infusion of EVs from young serum, which induced certain changes in the aged thymic microstructure, could improve aged thymic function in central tolerance generation, such as improvement of negative selection. If this were the case, it should enhance the depletion of self-reactive T clones, thereby helping to ameliorate inflammaging. As we know, the autoimmune regulator (Aire) gene regulates self-antigen presentation in mTECs, and its decreased expression is associated with loss or disorganization of mTECs in the aged thymus (42, 43). We also know that Nur77 expression in CD4+ thymocytes is a negative selection signal (58, 59), and higher expression of CD5 in CD4+ thymocytes triggers negative selection in the thymus (60). We observed that these molecules were all decreased in intensity in the aged thymus (61) and re-elevated after treatment with EVs from young serum (Fig. 6). Again, we confirmed that old mice that were treated with EVs from aged serum or young non-EV serum supernatant did not induce the rejuvenation of Aire expression in the old thymuses (Fig. 6A, bottom, B). These results suggest that efficient presentation of self-antigens to enhance the depletion of self-reactive T clones potentially occurs as a result of increased Aire expression, as well as increased markers of negative selection, Nur77 and CD5, that accompany T-cell receptor activation.

Figure 6.

EVs extracted from young serum induced an increase in negative selection–associated molecules in the aged thymus. A) Representative immunofluorescence staining images of Aire+ TECs (red) in K8+ TEC background (green). Original magnification, ×20. Top panels are young mice that were treated with PBS and aged mice treated with PBS and EVs from young serum, whereas bottom panels are aged mice that were treated with EVs from aged serum and young non-EV serum supernatant. Data are representative of 5 mouse thymuses per treatment group with essentially identical results. B) A summarized result shows the percent area of Aire+ TECs under K8+ counterstaining on the basis of slides in panel A. Each symbol represents 1 thymic tissue slide with ∼9 tissue slides for each mouse, calculated using ImageJ software. C) Real-time RT-PCR results show the expression of Aire mRNA in the aged thymuses. Aire expression was increased in aged mice that were treated with EVs from young serum compared with aged mice that were treated with PBS vehicle. D) Nur77 signaling strength was increased in CD4+ thymocytes of aged mice that were treated with EVs from young serum. Left panel shows histogram of Nur77 in CD4+ population, and the right panel shows a summary of relative Nur77 mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) in CD4+ populations of 3 groups of mice. E) CD5 signaling strength was increased in CD4+ thymocytes of the same aged mice as in panel D. Left panel shows histogram of CD5 in CD4+ population, and right panel shows a summary of relative CD5 MFI in CD4+ populations of 3 groups of mice. P values are shown in each panel, each symbol represents an individual animal sample.

Chronic autoimmune predisposition and features involved in inflammaging were reduced in aged mice after treatment with EVs from young serum

Inflammaging is believed to be subclinical autoimmunity (62) associated with increased self-reactivity (42, 43). We also wanted to directly observe any improvement of autoimmune predisposition or features in the periphery of aged mice that were treated with EVs from young serum. Therefore, we first checked ANA levels, which are autoantibodies that bind to the contents of the self-nucleus. These are increased with aging and are likely self-reactive CD4+ T cell dependent (63, 64). Meanwhile, we isolated splenic lymphocytes and adoptively transplanted them into young Rag−/− mice, which do not possess T or B cells. We then assessed inflammatory cell infiltration in the salivary glands of these host mice at 8 wk after transfer (workflow is shown in Fig. 7A). Our results demonstrate that the concentration of serum ANAs was increased in aged mice, whereas treatment with EVs from young serum indeed significantly reduced serum ANAs in aged mice (Fig. 7B, filled square symbols). We also found that average densities of pathologic foci of inflammatory cell infiltration—surrounded by yellow dotted lines—in the salivary glands of young Rag−/− mice, which were injected with splenic lymphocytes isolated from aged mice that were treated with EVs from young serum, were obviously reduced (Fig. 7C right) compared with mice that were injected with PBS only (Fig. 7C, middle); however, in the salivary glands of Rag−/− mice that were injected with young healthy splenic lymphocytes, we did not find pathologic foci of lymphocyte infiltration (Fig. 7C, left). Increased ANAs and severe lymphocyte infiltration in salivary glands are signs of autoimmune diseases, such as Sjogren’s syndrome. Although ANAs are produced by plasma cells after B-cell activation, this activation is dependent on 2 signals, antigen and primed T-helper cells (65). In this case, T-helper cells are likely self-reactive T cells primed by self-antigen that were released by the aged, atrophied thymus-released self-reactive T cells primed by self-antigen. However, EVs extracted from young serum were able to decrease these autoimmune phenotypes, which implies some therapeutic potential.

Figure 7.

Chronic autoimmune predisposition or features during inflammaging were reduced in aged mice after treatment with EVs extracted from young serum. A) A schematic workflow shows the process of naturally aged mice that were treated with EVs extracted from young serum, followed by isolation of their serum for analysis of ANAs and isolation of their splenic lymphocytes for adoptive transfer into young Rag−/− mice. Subsequently, inflammatory cell infiltration into a nonlymphoid organ, namely the salivary gland, was analyzed with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining at 8 wk after transfer. B) Concentrations of serum ANAs were increased in aged mice, but significantly reduced after treatment with EVs from young serum (see Materials and Methods). A Student’s t test was used, and P values are shown in each panel. Each symbol represents an individual animal sample. C) Representative H&E staining images of inflammatory cell infiltration in salivary glands of young Rag−/− mice, which were infused with spleen lymphocytes from young (treated with PBS, left), aged (treated with PBS, middle), and aged (treated with EVs from young serum, right) mice. Blue arrows indicate microvessels, and yellow dotted lines show the foci of infiltrating lymphocytes from microvessels. Numbers in top panels indicate the numbers of pathologic foci observed in 120 tissue slides. Data are representative of 3 biologic replicates in each group with essentially identical results.

DISCUSSION

Young blood-borne soluble factors have been accepted as being capable of rejuvenating aged systems, such as the skeletal muscle (2) and the CNS (1), through the improvement of the aged microenvironment, thereby promoting tissue-specific stem-cell activation. Although it seems that there may be multiple blood-borne soluble factors, we demonstrate with a mouse model that EVs or exosomes extracted from young serum are potentially such actors through which noncoding microRNAs, acting as a post-transcriptional or epigenetic regulators, attenuate inflammaging. Recently, circulating miRNAs, which are borne as cargo within exosomes (66), have been proposed to regulate neurodegenerative diseases (67), age-related cardiovascular diseases (23), and inflammaging (21, 22). We provide precise evidence regarding the attenuation of inflammaging in the periphery, such as a reduction of circulating and intracellular proinflammatory cytokines and factors (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ; Fig. 2), and in the CNS, such as a reduction of CNS-penetrating CD3+ T cells and Mϕs, and MHC-II expression by microglia (Fig. 3). These changes should make the aged milieu younger to promote the capacity for recovery of injured tissue as in the young system (Supplemental Fig. 1) and rejuvenate the effects of immunosenescence to promote immune response (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Generally, the etiology of the sustained increase in proinflammatory factors in the elderly is believed to be a mixture of multiple factors. They are senescent cell–produced SASP and tissue damage from the continuous activation of immune cells. Continuous activation of immune cells can be induced by latent viral (such as cytomegalovirus), infection (32, 34, 39–41), and self-reactivity of autoimmune T cells released from the aged, atrophied thymus as a result of the age-related perturbation of immunotolerance establishment (42, 43). The latter, self-reactive T cell–induced self-tissue damage, is more harmful and has severe long-term effects. Our data indeed provide evidence that the attenuation of inflammaging by EVs extracted from young serum is associated with the rejuvenation of immunotolerance in the aged thymus, such as an increase of thymic mass (Fig. 4), improvement of aged thymic microstructure (Fig. 5), and enhancement of expression of the molecules that are involved in negative selection (Fig. 6), thereby demonstrating reduced autoimmune phenotypes (Fig. 7).

In our results, all improvements after treatment with EVs from young mouse serum were significant, but cannot restore to the same level as in the young system. For example, although the expression of ΔNp63 and FoxN1, which are key transcription factors that regulate thymic epithelial stem-cell proliferation and differentiation to prevent thymic involution (50), was increased, the thymic mass was still less compared with the young thymus. This highlights the limitation of temporary treatment with EVs from young serum, and also suggests that there are multiple factors and mechanisms involved. In addition, a transient effect of treatment with EVs from young serum may not fully restore the growth capacity of the thymus, but only regulate thymic function by shutting down or turning on certain transcription factors. This could explain why the previous works that used the heterochronic parabiosis model, which focused only on restoring the growth capacity of the thymus, did not report positive effects (3, 13).

EVs act as carriers and transfer pools of miRNAs between cells. The post-transcriptional regulation by miRNAs is via an integrated network that is involved in transcriptional repression or enhancement. A single miRNA can regulate multiple genes, whereas a single gene can be regulated by multiple miRNAs. miRNAs can directly suppress gene expression, and can also suppress an inhibitor, indirectly turning on other genes that were suppressed by this inhibitor. Given that EVs or exosomes also contain proteins and lipids, the mechanism by which the complicated and intricate factors from EVs extracted from young serum regulate inflammaging, such as potentially rejuvenating senescent cells, still needs to be investigated further. In addition to the function of miRNA on immunotolerance and senescent cells, we also cannot exclude direct action of miRNA on aged tissues. For example, studies by Villeda et al. (1), which used young blood to rejuvenate the aged CNS, also revealed that a young blood–associated factor is able to directly activate cAMP response element binding protein in hippocampal-dependent cognitive enhancement.

Applying the soluble factors derived from young blood to rejuvenate aged systems is a promising strategy for interventional medicine that can potentially cure or prevent many age-related diseases, including such neurocardiovascular diseases as Alzheimer’s disease and heart disease; however, using the heterochronic parabiosis model to study rejuvenation is not practical. In addition to being a difficult model to establish, some unknown aging factors may have the reverse effect on the young milieu in a young-old animal combined circulation system (3, 8). The heterochronic parabiosis model may reveal systemic inhibitory factors in aged blood, but we can study this topic by infusing aged blood into the young system instead of using the heterochronic parabiosis model. If there exist some systemic inhibitory factors in aged blood, EVs extracted from young donor serum may provide counteracting factors, such as miRNAs, to suppress them in aged individuals to rejuvenate systemic aging.

In summary, we have explored how EVs extracted from young serum mediate post-transcriptional regulation (68, 69), and how they play a role in anti-inflammaging by rejuvenating aged immunotolerance function. These results are expected to establish a basis for the eventual development of effective and practical therapeutics via epigenetic reprogramming (27) in elderly individuals who are at risk for chronic inflammation–associated cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant R01-AI121147 (to D.-M.S.), and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31660256; to L.W.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- ANA

antinuclear antibody

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- cTEC

cortical thymic epithelial cell

- EV

extracellular vesicle

- K5

keratin-5

- Mϕ

macrophage

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- miRNA

microRNA

- mTEC

medullary thymic epithelial cell

- SASP

senescence-associated secretory phenotype

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W. Wang performed most of the experiments and prepared figures and the manuscript; L. Wang and L. Ruan performed part of experiments related to inflammation; J. Oh performed part of experiments related to gene expression; X. Dong performed EV and exosome analysis; Q. Zhuge provided instruction on studies of neuronal inflammation; and D.-M. Su designed the overall research project, instructed experiments, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Villeda S. A., Plambeck K. E., Middeldorp J., Castellano J. M., Mosher K. I., Luo J., Smith L. K., Bieri G., Lin K., Berdnik D., Wabl R., Udeochu J., Wheatley E. G., Zou B., Simmons D. A., Xie X. S., Longo F. M., Wyss-Coray T. (2014) Young blood reverses age-related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nat. Med. 20, 659–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conboy I. M., Conboy M. J., Wagers A. J., Girma E. R., Weissman I. L., Rando T. A. (2005) Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature 433, 760–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pishel I., Shytikov D., Orlova T., Peregudov A., Artyuhov I., Butenko G. (2012) Accelerated aging versus rejuvenation of the immune system in heterochronic parabiosis. Rejuvenation Res. 15, 239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruckh J. M., Zhao J. W., Shadrach J. L., van Wijngaarden P., Rao T. N., Wagers A. J., Franklin R. J. (2012) Rejuvenation of regeneration in the aging central nervous system. Cell Stem Cell 10, 96–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brack A. S., Conboy M. J., Roy S., Lee M., Kuo C. J., Keller C., Rando T. A. (2007) Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science 317, 807–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loffredo F. S., Steinhauser M. L., Jay S. M., Gannon J., Pancoast J. R., Yalamanchi P., Sinha M., Dall’Osso C., Khong D., Shadrach J. L., Miller C. M., Singer B. S., Stewart A., Psychogios N., Gerszten R. E., Hartigan A. J., Kim M. J., Serwold T., Wagers A. J., Lee R. T. (2013) Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell 153, 828–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katsimpardi L., Litterman N. K., Schein P. A., Miller C. M., Loffredo F. S., Wojtkiewicz G. R., Chen J. W., Lee R. T., Wagers A. J., Rubin L. L. (2014) Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science 344, 630–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villeda S. A., Luo J., Mosher K. I., Zou B., Britschgi M., Bieri G., Stan T. M., Fainberg N., Ding Z., Eggel A., Lucin K. M., Czirr E., Park J. S., Couillard-Després S., Aigner L., Li G., Peskind E. R., Kaye J. A., Quinn J. F., Galasko D. R., Xie X. S., Rando T. A., Wyss-Coray T. (2011) The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature 477, 90–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villeda S. A., Wyss-Coray T. (2013) The circulatory systemic environment as a modulator of neurogenesis and brain aging. Autoimmun. Rev. 12, 674–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha M., Jang Y. C., Oh J., Khong D., Wu E. Y., Manohar R., Miller C., Regalado S. G., Loffredo F. S., Pancoast J. R., Hirshman M. F., Lebowitz J., Shadrach J. L., Cerletti M., Kim M. J., Serwold T., Goodyear L. J., Rosner B., Lee R. T., Wagers A. J. (2014) Restoring systemic GDF11 levels reverses age-related dysfunction in mouse skeletal muscle. Science 344, 649–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egerman M. A., Cadena S. M., Gilbert J. A., Meyer A., Nelson H. N., Swalley S. E., Mallozzi C., Jacobi C., Jennings L. L., Clay I., Laurent G., Ma S., Brachat S., Lach-Trifilieff E., Shavlakadze T., Trendelenburg A. U., Brack A. S., Glass D. J. (2015) GDF11 increases with age and inhibits skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Metab. 22, 164–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brun C. E., Rudnicki M. A. (2015) GDF11 and the mythical fountain of youth. Cell Metab. 22, 54–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim M. J., Miller C. M., Shadrach J. L., Wagers A. J., Serwold T. (2015) Young, proliferative thymic epithelial cells engraft and function in aging thymuses. J. Immunol. 194, 4784–4795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bobrie A., Colombo M., Raposo G., Théry C. (2011) Exosome secretion: molecular mechanisms and roles in immune responses. Traffic 12, 1659–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colombo M., Raposo G., Théry C. (2014) Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 30, 255–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartel D. P. (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He L., Hannon G. J. (2004) MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 522–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambros V. (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo A., Tandon M., Alevizos I., Illei G. G. (2012) The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS One 7, e30679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valadi H., Ekström K., Bossios A., Sjöstrand M., Lee J. J., Lötvall J. O. (2007) Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 654–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berdasco M., Esteller M. (2012) Hot topics in epigenetic mechanisms of aging: 2011. Aging Cell 11, 181–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olivieri F., Rippo M. R., Monsurrò V., Salvioli S., Capri M., Procopio A. D., Franceschi C. (2013) MicroRNAs linking inflamm-aging, cellular senescence and cancer. Ageing Res. Rev. 12, 1056–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olivieri F., Rippo M. R., Procopio A. D., Fazioli F. (2013) Circulating inflamma-miRs in aging and age-related diseases. Front. Genet. 4, 121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Candia P., Torri A., Pagani M., Abrignani S. (2014) Serum microRNAs as biomarkers of human lymphocyte activation in health and disease. Front. Immunol. 5, 43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calvanese V., Lara E., Kahn A., Fraga M. F. (2009) The role of epigenetics in aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 8, 268–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson A. G. (2008) Epigenetic regulation of gene expression in the inflammatory response and relevance to common diseases. J. Periodontol. 79 (Suppl), 1514–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rando T. A., Chang H. Y. (2012) Aging, rejuvenation, and epigenetic reprogramming: resetting the aging clock. Cell 148, 46–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraga M. F. (2009) Genetic and epigenetic regulation of aging. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21, 446–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Théry C., Ostrowski M., Segura E. (2009) Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 581–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Martinis M., Franceschi C., Monti D., Ginaldi L. (2005) Inflamm-ageing and lifelong antigenic load as major determinants of ageing rate and longevity. FEBS Lett. 579, 2035–2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franceschi C., Bonafè M., Valensin S., Olivieri F., De Luca M., Ottaviani E., De Benedictis G. (2000) Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 908, 244–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunner S., Herndler-Brandstetter D., Weinberger B., Grubeck-Loebenstein B. (2011) Persistent viral infections and immune aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 10, 362–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freund A., Orjalo A. V., Desprez P. Y., Campisi J. (2010) Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 238–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franceschi C., Capri M., Monti D., Giunta S., Olivieri F., Sevini F., Panourgia M. P., Invidia L., Celani L., Scurti M., Cevenini E., Castellani G. C., Salvioli S. (2007) Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech. Ageing Dev. 128, 92–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coder B., Wang W., Wang L., Wu Z., Zhuge Q., Su D. M. (2017) Friend or foe: the dichotomous impact of T cells on neuro-de/re-generation during aging. Oncotarget 8, 7116–7137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campisi J. (2011) Cellular senescence: putting the paradoxes in perspective. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 21, 107–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivieri F., Spazzafumo L., Santini G., Lazzarini R., Albertini M. C., Rippo M. R., Galeazzi R., Abbatecola A. M., Marcheselli F., Monti D., Ostan R., Cevenini E., Antonicelli R., Franceschi C., Procopio A. D. (2012) Age-related differences in the expression of circulating microRNAs: miR-21 as a new circulating marker of inflammaging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 133, 675–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olivieri F., Lazzarini R., Recchioni R., Marcheselli F., Rippo M. R., Di Nuzzo S., Albertini M. C., Graciotti L., Babini L., Mariotti S., Spada G., Abbatecola A. M., Antonicelli R., Franceschi C., Procopio A. D. (2013) miR-146a as marker of senescence-associated pro-inflammatory status in cells involved in vascular remodelling. Age (Dordr.) 35, 1157–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikolich-Zugich J. (2008) Ageing and life-long maintenance of T-cell subsets in the face of latent persistent infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 512–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.High K. P., Akbar A. N., Nikolich-Zugich J. (2012) Translational research in immune senescence: assessing the relevance of current models. Semin. Immunol. 24, 373–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Licastro F., Candore G., Lio D., Porcellini E., Colonna-Romano G., Franceschi C., Caruso C. (2005) Innate immunity and inflammation in ageing: a key for understanding age-related diseases. Immun. Ageing 2, 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia J., Wang H., Guo J., Zhang Z., Coder B., Su D. M. (2012) Age-related disruption of steady-state thymic medulla provokes autoimmune phenotype via perturbing negative selection. Aging Dis. 3, 248–259 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coder B. D., Wang H., Ruan L., Su D. M. (2015) Thymic involution perturbs negative selection leading to autoreactive T cells that induce chronic inflammation. J. Immunol. 194, 5825–5837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coder B., Su D. M. (2015) Thymic involution beyond T-cell insufficiency. Oncotarget 6, 21777–21778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrall A. J., Wardlaw J. M. (2009) Blood-brain barrier: ageing and microvascular disease—systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 337–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucin K. M., Wyss-Coray T. (2009) Immune activation in brain aging and neurodegeneration: too much or too little? Neuron 64, 110–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng L., Guo J., Sun L., Fu J., Barnes P. F., Metzger D., Chambon P., Oshima R. G., Amagai T., Su D. M. (2010) Postnatal tissue-specific disruption of transcription factor FoxN1 triggers acute thymic atrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5836–5847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Legroux L., Pittet C. L., Beauseigle D., Deblois G., Prat A., Arbour N. (2015) An optimized method to process mouse CNS to simultaneously analyze neural cells and leukocytes by flow cytometry. J. Neurosci. Methods 247, 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li T., Zhai X., Jiang J., Song X., Han W., Ma J., Xie L., Cheng L., Chen H., Jiang L. (2017) Intraperitoneal injection of IL-4/IFN-γ modulates the proportions of microglial phenotypes and improves epilepsy outcomes in a pilocarpine model of acquired epilepsy. Brain Res. 1657, 120–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burnley P., Rahman M., Wang H., Zhang Z., Sun X., Zhuge Q., Su D. M. (2013) Role of the p63-FoxN1 regulatory axis in thymic epithelial cell homeostasis during aging. Cell Death Dis. 4, e932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keerthikumar S., Gangoda L., Liem M., Fonseka P., Atukorala I., Ozcitti C., Mechler A., Adda C. G., Ang C. S., Mathivanan S. (2015) Proteogenomic analysis reveals exosomes are more oncogenic than ectosomes. Oncotarget 6, 15375–15396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexander M., Hu R., Runtsch M. C., Kagele D. A., Mosbruger T. L., Tolmachova T., Seabra M. C., Round J. L., Ward D. M., O’Connell R. M. (2015) Exosome-delivered microRNAs modulate the inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nat. Commun. 6, 7321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Toro J., Herschlik L., Waldner C., Mongini C. (2015) Emerging roles of exosomes in normal and pathological conditions: new insights for diagnosis and therapeutic applications. Front. Immunol. 6, 203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams K. A., Hart D. N., Fabre J. W., Morris P. J. (1980) Distribution and quantitation of HLA-ABC and DR (Ia) antigens on human kidney and other tissues. Transplantation 29, 274–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Korn T., Kallies A. (2017) T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 179–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bredenkamp N., Nowell C. S., Blackburn C. C. (2014) Regeneration of the aged thymus by a single transcription factor. Development 141, 1627–1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zook E. C., Krishack P. A., Zhang S., Zeleznik-Le N. J., Firulli A. B., Witte P. L., Le P. T. (2011) Overexpression of Foxn1 attenuates age-associated thymic involution and prevents the expansion of peripheral CD4 memory T cells. Blood 118, 5723–5731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Starr T. K., Jameson S. C., Hogquist K. A. (2003) Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 139–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moran A. E., Holzapfel K. L., Xing Y., Cunningham N. R., Maltzman J. S., Punt J., Hogquist K. A. (2011) T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1279–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Azzam H. S., DeJarnette J. B., Huang K., Emmons R., Park C. S., Sommers C. L., El-Khoury D., Shores E. W., Love P. E. (2001) Fine tuning of TCR signaling by CD5. J. Immunol. 166, 5464–5472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oh J., Wang W., Thomas R., Su D. M. (2017) Capacity of tTreg generation is not impaired in the atrophied thymus. PLoS Biol. 15, e2003352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giunta S. (2006) Is inflammaging an auto[innate]immunity subclinical syndrome? Immun. Ageing 3, 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakken B., Davis K. E., Pan Z. J., Bachmann M., Farris A. D. (2003) T-helper cell tolerance to ubiquitous nuclear antigens. Scand. J. Immunol. 58, 478–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nusser A., Nuber N., Wirz O. F., Rolink H., Andersson J., Rolink A. (2014) The development of autoimmune features in aging mice is closely associated with alterations of the peripheral CD4+ T-cell compartment. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 2893–2902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baumgarth N. (2000) A two-phase model of B-cell activation. Immunol. Rev. 176, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katsuda T., Kosaka N., Takeshita F., Ochiya T. (2013) The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Proteomics 13, 1637–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheinerman K. S., Umansky S. R. (2013) Circulating cell-free microRNA as biomarkers for screening, diagnosis and monitoring of neurodegenerative diseases and other neurologic pathologies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7, 150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu L., Zhou H., Zhang Q., Zhang J., Ni F., Liu C., Qi Y. (2010) DNA methylation mediated by a microRNA pathway. Mol. Cell 38, 465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iorio M. V., Piovan C., Croce C. M. (2010) Interplay between microRNAs and the epigenetic machinery: an intricate network. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 694–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.