Abstract

Enhancer of zeste homolog-2 (EZH2) is a methyltransferase that induces histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and functions as an oncogenic factor in many cancer types. Its role in renal epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) remains unknown. In this study, we found that EZH2 and H3K27me3 were highly expressed in mouse kidney with unilateral ureteral obstruction and cultured mouse kidney proximal tubular (TKPT) cells undergoing EMT. Inhibition of EZH2 with 3-deazaneplanocin A (3-DZNeP) attenuated renal fibrosis, which was associated with preserving E-cadherin expression and inhibiting Vimentin up-regulation in the obstructed kidney. Treatment with 3-DZNeP or transfection of EZH2 siRNA also inhibited TGF-β1–induced EMT of TKPT cells. Injury to the kidney or cultured TKPT cells resulted in up-regulation of Snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (Snail-1) and Twist family basic helix-loop-helix (BHLH) transcription factor 1 (Twist-1), which are 2 transcription factors, and down-regulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog, a protein tyrosine phosphatase associated with inhibition of PI3K-protein kinase B (AKT) signaling; EZH2 inhibition or silencing reversed all those responses. 3-DZNeP was also effective in suppressing epithelial arrest at the G2/M phase and dephosphorylating AKT and β-catenin in vivo and in vitro. These data indicate that EZH2 activation contributes to renal EMT and fibrosis through activation of multiple signaling pathways and suggest that EZH2 has potential as a therapeutic target for treatment of renal fibrosis.—Zhou, X., Xiong, C., Tolbert, E., Zhao, T. C., Bayliss, G., Zhuang, S. Targeting histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homolog-2 inhibits renal epithelial–mesenchymal transition and attenuates renal fibrosis.

Keywords: Snail, Twist, PTEN, AKT, EMT

The pathogenesis of chronic renal disease is characterized by continuous accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM), which leads to a diffuse fibrosis and progressive decline of renal function (1, 2). Activation and proliferation of renal interstitial fibroblasts are critically involved in the overproduction of ECM components and progression of interstitial fibrosis. Multiple cytokines and growth factors have been identified as mediators of interstitial renal fibroblast activation, including TGF-β1 and connective tissue growth factor (3). Although several cell types in the kidney have been reported to contribute to production of fibrogenic cytokines and growth factors, a study has demonstrated that renal tubular cells under maladaptive repair after chronic injury serve as the primary profibrotic cell type (4). An important feature of the maladaptive repair process after injury is the development of cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase of cell cycle (5). Formation of this cell type is the functional consequence of the partial epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) program during fibrotic injury (6, 7). Therefore, identification of the mechanisms that mediate EMT will aid in the development of novel treatments for renal fibrosis (8).

Partial EMT is defined as the state in which epithelial cells express markers of both epithelial and mesenchymal cells, but remain associated with the basement membrane (6, 7). This concept is different from complete EMT, in which epithelial cells lose their polarity and cell–cell adhesion and gain the ability to migrate into the interstitium and differentiate into myofibroblasts (9). Although it was initially thought that complete EMT occurs during the process of renal fibrosis, genetic approaches identified very few or no myofibroblasts derived from renal epithelial cells in the interstitium (7, 10). The partial EMT program in renal epithelial cells may play a predominant role in the development of renal fibrosis. This notion is supported by the observations that renal epithelial cells with EMT result in loss of function, induction of cell cycle arrest, and production of profibrotic factors that stimulate renal fibroblast activation and ECM deposition (7). In addition, TGF-β1–induced EMT of renal epithelial cells results in cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase (7).

The molecular mechanism that regulates the partial EMT of renal epithelial cells after chronic injury remains incompletely understood. Activation of transcriptional factors such as Twist family basic helix-loop-helix (BHLH) transcription factor 1 (Twist-1) or Snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (Snail-1) may be the key step for initiation of this process. It has been documented that conditional deletion of Twist-1 or Snail-1 in proximal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) led to inhibition of the EMT program and G2/M arrest, and TGF-β1–induced EMT and G2 phase cell cycle arrest requires Twist-1 and Snail-1 (7). Other signaling pathways such as protein kinase B (AKT) and β-catenin also mediate the EMT program by activation of some transcription factors that drive expression of some profibrotic genes (11–13). In addition, recent studies have shown that epigenetic modifications can participate in the expression of profibrotic genes and contribute to renal fibrogenesis through regulating activation of intracellular signaling pathways and gene expression (14, 15).

Epigenetics refers to the modulation of gene expression via post-translational modification of protein complexes associated with DNA, without changing the DNA sequence (16, 17). Among the several protein/histone modifications are acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation (17, 18). Protein methylation can occur in histone and nonhistone proteins and is induced by multiple histone lysine methyltransferases, including enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2). EZH2 is the functional component of the polycomb repressive complex-2 (19) and can specifically mediate histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3), a transcriptionally repressive epigenetic mark associated with suppression of multiple tumor suppressor genes and initiation of tumorigenesis (20–22). In a recent study, we reported that blocking EZH2 activation with 3-deazaneplanocin A (3-DZNeP), a carbocyclic analog of adenosine, inhibits the activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts and attenuates the development of renal fibrosis (23). The role of EZH2 inhibition in the regulation of renal EMT and the mechanisms involved remain unknown.

In the current study, we examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on the development of renal EMT and analyzed the associated mechanisms in a mouse model of unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) and cultured renal TECs stimulated by TGF-β1. Our results indicate that EZH2 is highly expressed in the fibrotic kidneys. Down-regulation of EZH2 results in suppression of EMT and renal fibrosis by blocking multiple signaling pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and antibodies

Antibodies to E-cadherin, Vimentin, SNAIL-1, TWIST, β-catenin, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). 3-Deazaneplanocin A (DZNeP) was purchased from Active Biochem (Maplewood, NJ, USA) and Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA). α-Tubulin and all other chemicals were purchased from MilliporeSigma (Burlington, MA, USA). Small interfering (si)RNA, specific for rat EZH2 was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). All other antibodies used in this study were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA).

Cell culture and treatment

Immortalized mouse kidney proximal tubular (TKPT) cells were cultured in DMEM with F12 containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% penicillin, and streptomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, and 95% air at 37°C. To determine the effect of 3-DZNeP on TGF-β1–induced renal EMT, TKPT cells were starved for 24 h with DMEM/F12 without fetal bovine serum and then exposed to TGF-β1 for the various times in the presence or absence of EZH2 inhibitor.

Transfection of siRNA into cells

The siRNA oligonucleotides, targeted specifically to rat EZH2, were used to down-regulate EZH2. In a 6-well plate, TKPT cells were seeded to 50–60% confluence in antibiotic-free medium and grown for 24 h. Then, cells in each well were transfected with siRNA (100 pmol) specific for EZH2 with Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In parallel, scrambled siRNA (100 pmol) was used as a control for off-target changes in TKPT cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was changed and cells were incubated for an additional 24 h before being harvested for analysis.

Animals and experimental design

The UUO model was established in male C57 black mice that weighed 20–25 g (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) as described in our previous studies (24, 25). In brief, the abdominal cavity was exposed via a midline incision, and the left ureter was isolated and ligated. The contralateral kidney was used as a control. To examine the role of EZH2 in renal fibrosis, 3-DZNeP (2 mg/kg, in 50 µl of DMSO, i.p.) was administered immediately after ureteral ligation and then given daily for 13 d. The dose of 3-DZNeP as selected according to a previous report (26). For the UUO-alone group, mice were injected with an equivalent amount of DMSO. The animals were euthanized, and the kidneys were collected at d 14 after UUO for protein analysis and histologic examination. All experimental procedures were performed according to the NIH Guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Lifespan Animal Welfare Committee (Providence, RI, USA).

Immunoblot analysis

To prepare protein samples for Western blot analysis, we homogenized the kidney tissue samples with cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN, USA). After various treatments, the cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and harvested in a cell lysis buffer mixed with a protease inhibitor cocktail. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After incubation with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with a primary antibody overnight at 4°C and then incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Bound antibodies were visualized by chemiluminescence detection.

Histochemical and immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent staining was performed according to the procedure described in our previous studies. Renal tissue was fixed in 4.5% buffered formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. For general histology, sections were stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS). Masson trichrome staining was performed according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (MilliporeSigma). For assessment of renal fibrosis quantitatively, the collagen tissue area was measured using Image Pro-Plus Software (Media-Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA), by drawing a line around the perimeter of the positive staining area, and the average ratio to each microscopic field was calculated and graphed. For immunofluorescent staining, rabbit anti-E-cadherin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-Vimentin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-PTEN, and rabbit anti-p-β-catenin (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies were used.

Densitometry analysis

The semiquantitative analysis of different proteins was performed with Image J software developed at the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). The quantification is based on the intensity (density) of the band, which is calculated by the area and pixel value of the band. The quantification data are given as a ratio between target protein and loading control (housekeeping protein).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± sd and were subjected to 1-way ANOVA. Multiple means were compared by using Tukey’s test, and differences between 2 groups were determined by Student’s t test. Values of P < 0.05 were statistically significant.

RESULTS

EZH2 inhibition attenuates renal fibrosis and H3K27 methylation after obstruction injury

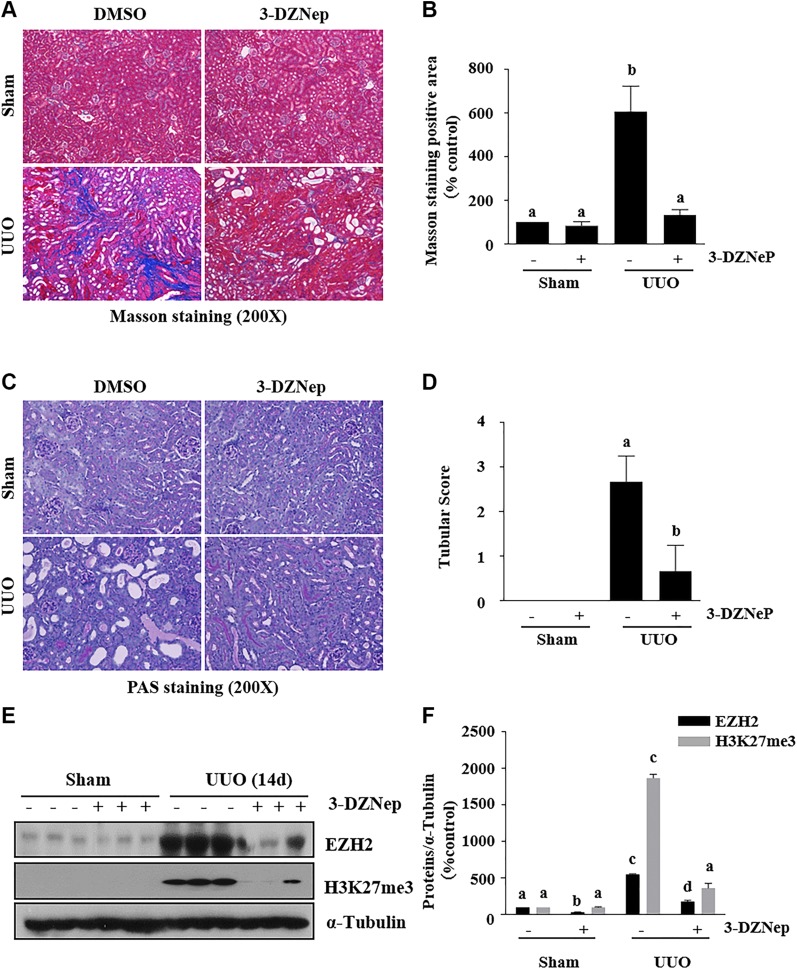

To assess the role of EZH2 in the development of renal fibrosis, we examined the effect of 3-DZNeP on the development of renal fibrosis in a murine model of renal fibrosis induced by UUO. At d 14 after ureteral ureter ligation with or without administration of 3-DZNeP, the kidneys were collected and then subjected to Masson trichrome and PAS staining to analyze renal fibrosis and pathologic changes. UUO injury induced expression of interstitial collagen fibrils, as indicated by Masson trichrome staining, and administration of 3-DZNep at a dose of 2 mg/kg resulted in a dramatic attenuation of collagen fibril deposition (Fig. 1A, B). A semiquantitative analysis of Masson trichrome-positive areas reveals a 6-fold increase of ECM in obstructed kidneys compared to sham-operation kidneys. 3-DZNep treatment resulted in ∼80% less renal fibrosis in the obstructed kidney than in the untreated UUO kidney. In addition, there were fewer pathologic changes in the injured kidney after 3-DZNeP treatment, as indicated by PAS staining (Fig. 1C, D).

Figure 1.

Administration of 3-DZNeP attenuates development of renal fibrosis in obstructed kidneys. A, C) Photomicrographs illustrating Masson trichrome (A) and PAS (C) staining of kidney tissue after various treatments. Original magnification, ×200. B, D) The Masson trichrome–positive tubulointerstitial area (blue) relative to the whole area from 6 random cortical fields was analyzed (B), and kidney damage scoring was conducted in 6 random fields of each group (D). Data are means ± sd (n = 6). E) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against EZH2, H3K27me3, or α-tubulin. F) Expression levels of EZH2, H3K27me3, or α-tubulin were quantified by densitometry, and the levels of proteins were normalized with α-tubulin. Data are means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

To demonstrate whether renal fibrosis reduction is related to the inhibition of EZH2 activity, we used immunoblot analysis to examine the effect of 3-DZNeP on the expression of EZH2 and trimethylation of H3K27 in the murine kidney collected at d 14 after UUO. EZH2, but not H3K27me3, was detectable in the kidney of sham-operation mice (Fig. 1E, F), suggesting that EZH2 is minimally expressed, but not activated in the normal kidney. UUO injury induced a dramatic increase in the expression of renal EZH2, which was accompanied by increased levels of H3K27me3. Administration of 3-DZNeP reduced the increased expression of both EZH2 and H3K27me3 in the kidney of UUO-injured mice.

These results illustrate that EZH2 plays a critical role in the regulation of renal fibrosis development and that 3-DZNeP is a potent antifibrotic agent.

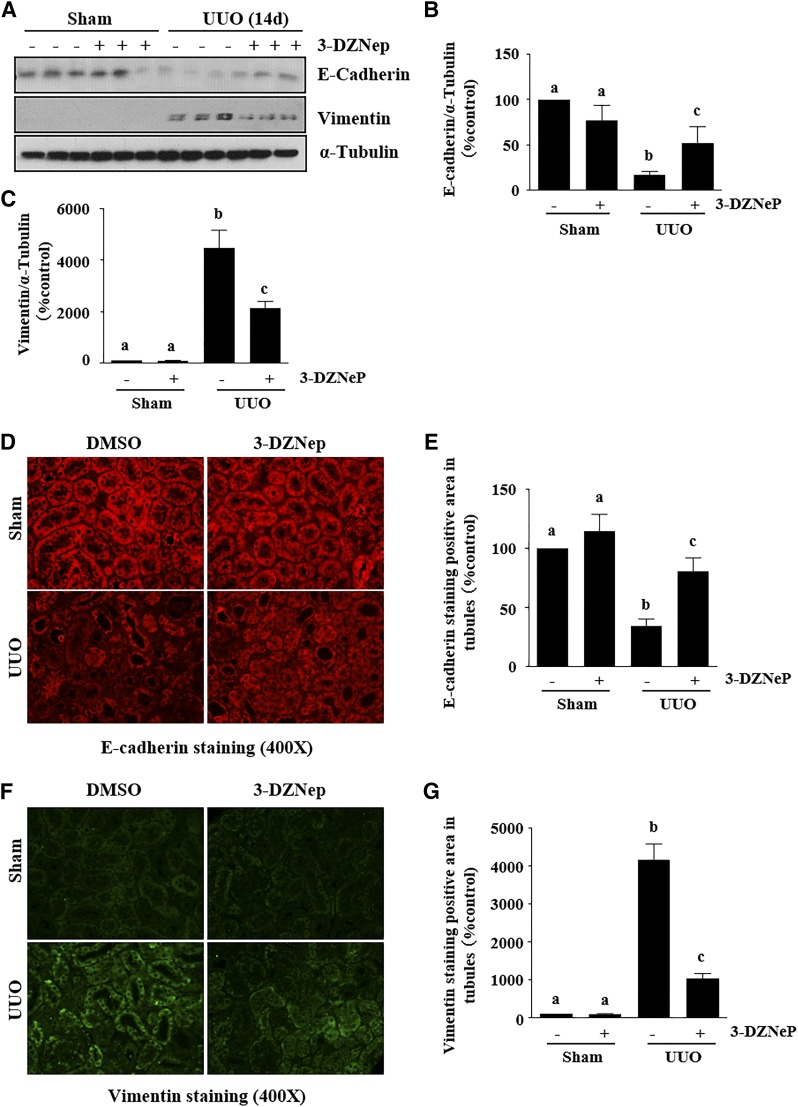

EZH2 inhibition attenuates renal EMT after obstruction injury

EMT is characterized by down-regulation of E-cadherin, a major component of adherens junctions, and up-regulation of some mesenchymal genes, including Vimentin, and genes that encode transcription factors such as Snail-1 and Twist (27, 28). To assess the role of EZH2 in the development of EMT, we examined the effect of 3-DZNeP on the expressions of E-cadherin, Vimentin Snail-1 and Twist in the murine model of renal fibrosis induced by UUO. As shown in immunoblot analysis of whole-kidney tissue lysate collected at d 14 after ureteral ureter ligation, there was a decrease in the expression of E-cadherin and increased expression of Vimentin (Fig. 2A–C), as well as Snail-1 and Twist (see Fig. 5) after UUO injury. Administration of 3-DZNeP remarkably reversed the expression of E-cadherin (∼50%) and Vimentin (∼60%). Immunofluorescent staining also showed decreased expression of E-cadherin and increased expression of Vimentin in the kidney after UUO injury and 3-DZNeP treatment reduced these responses (Fig. 2D–G).

Figure 2.

Administration of 3-DZNeP attenuates renal EMT in obstructed kidneys. A) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against E-cadherin, Vimentin, or α-tubulin. B, C) Expression levels of E-cadherin (B), Vimentin (C), and α-tubulin were quantified by densitometry, and the levels of proteins were normalized with α-tubulin. D, F) Photomicrographs illustrating E-cadherin (D) and vimentin (F) immunofluorescent staining of kidney tissue after various treatments. E, G) The positive tubular area of E-cadherin (E) and Vimentin (G) from 6 random cortical fields was analyzed. Values are means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

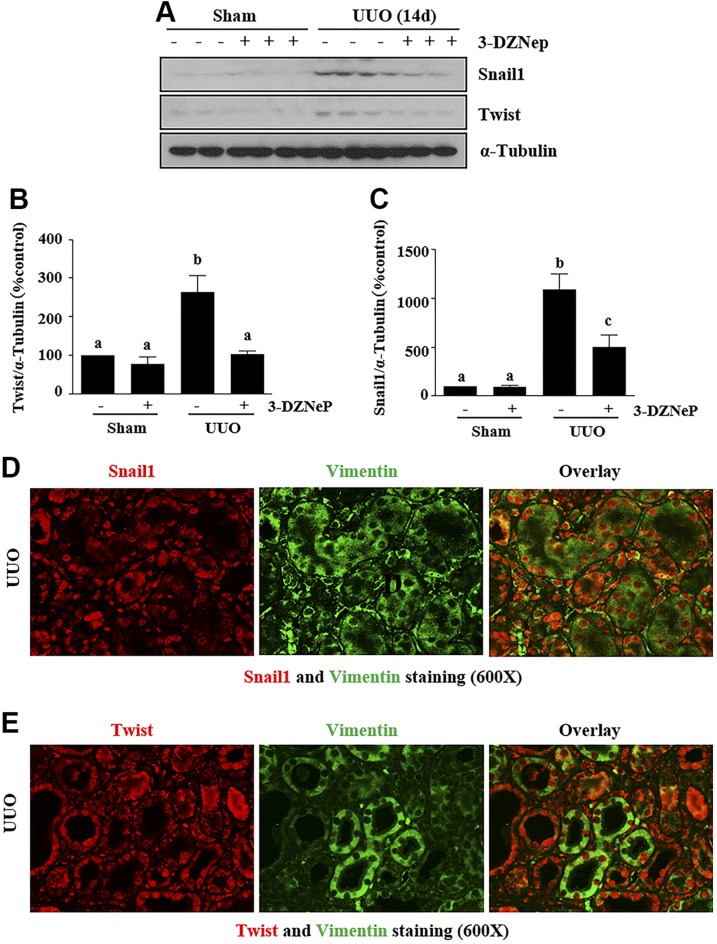

Figure 5.

EZH2 inhibition suppresses the expressions of Snail-1 and Twist in obstructed kidneys. A) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against Snail-1, Twist, and α-tubulin. B, C) Expression levels of Twist (B) and Snail-1 (C), both with and α-tubulin, were quantified by densitometry, and were normalized with α-tubulin. D, E) Photomicrographs illustrate Snail-1 and Vimentin (D) or Twist and Vimentin (E) in the obstructed kidney. Data are the means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

These data suggest that EZH2 activation is involved in the regulation of renal EMT in the kidney undergoing in renal fibrosis.

EZH2 mediates TGF-β1–induced EMT and histone methylation in cultured renal TECs

We examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on TGF-β1–induced renal EMT in light of the cytokine’s major role in the process. TKPT cells were serum starved for 24 h and then exposed to 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 in the absence or presence of 3-DZNeP. TGF-β1 treatment markedly decreased E-cadherin expression and increased Vimentin expression, indicating induction of EMT in renal epithelial cells (Fig. 3A, C). Treatment of TKPT with 3-DZNeP inhibited TGF-β1-induced attenuation of E-cadherin expression and increase of Vimentin expression. Similar results were observed in TGF-β1–treated TKPT with and without transfection with siRNA specifically to EZH2 (Fig. 3B, D). 3-DZNeP and EZH2 siRNA were both effective in inhibiting expression of EZH2 and H3K27me3 (Fig. 3A, B, E, F). In addition, we observed that 3-DZNeP blocked morphologic changes of TKPT (reduced cell–cell contact and elongated appearance) (Fig. 3G). These data confirm the importance of EZH2 in mediating EMT in renal epithelial cells.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of EZH2 suppresses the TGF-β1–induced renal EMT in proximal TECs. A, B) TKPT cells were serum starved for 24 h and treated with 3-DZNeP (10 µM) for 1 h (A) or transfected with EZH2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 24 h followed by exposure of cells to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis with antibodies against E-cadherin, Vimentin, EZH2, H3K27me3, and GAPDH. C–F) All proteins were quantified by densitometry, and were normalized to GAPDH. G) Photomicrographs illustrating TKPT cells treated with or without TGF-β induction in the presence or absence of 3-DZNeP for 24 h. Values are means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

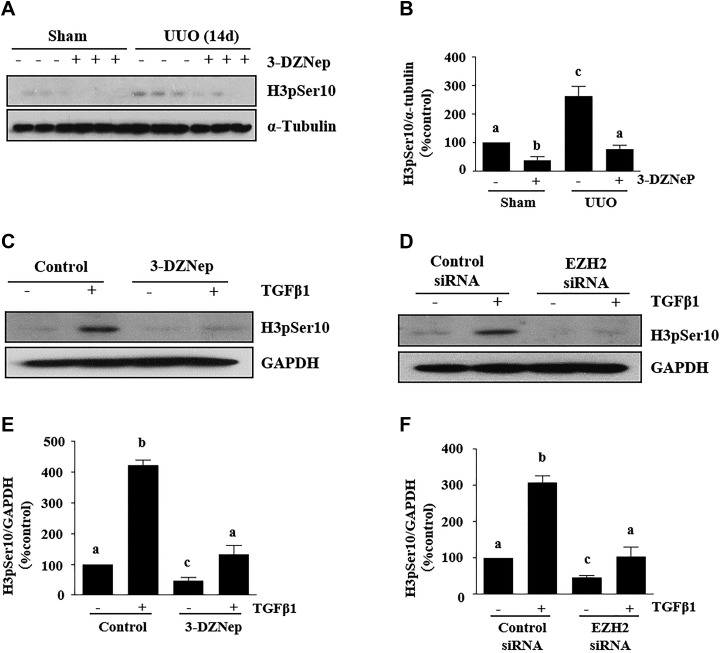

EZH2 inhibition reduces renal cells arrested at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle in mice with obstruction injury and TGF-β1-induced renal TECs

Chronic kidney disease is associated with an interruption of cell cycle progression, whereby fibrotic injury results in epithelial cell arrest in the G2/M, a biologic consequence of EMT (7). To probe whether EZH2 inhibition intervenes in the process of cell arrest, we examined the effect of 3-DZNeP on the expressions of phospho-histone H3 at serine 10 (H3pSer10), a hallmark of cell cycle arrested at the G2/M phase, in a murine model of renal fibrosis induced by UUO. Immunoblot analysis indicated that there was a dramatic increase in the expression of H3pSer10 in the kidney after 14 d of UUO injury (Fig. 4A, B). Administration of 3-DZNeP totally reversed the expression level of H3pSer10.

Figure 4.

EZH2 inhibition suppresses renal epithelial cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase in obstructed kidneys and TGF-β1–treated proximal TECs. A) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against H3pSer10 and α-tubulin. B) Expression levels H3pSer10 and α-tubulin were quantified by densitometry and were normalized with α-tubulin. C, D) TKPT cells were serum starved for 24 h and then treated with 3-DZNeP (10 µM) for 1 h (C) or transfected with EZH2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 24 h (D) followed by exposure of cells to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis with antibodies against H3pSer10 and GAPDH. E, F) All proteins were quantified by densitometry and were normalized to GAPDH. Values are means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

It has been reported that TGF-β1 stimulation of mouse TECs also results in a cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase. To confirm the role of EZH2 in renal cell arrest in the process of renal EMT, we examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on TGF-β1–induced renal TEC arrest at the G2/M phase. TKPT cells were serum starved for 24 h and exposed to 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 in the absence or presence of 3-DZNeP. TGF-β1 treatment of renal proximal tubular cells markedly increased the phosphorylation of H3Ser10, indicating renal epithelial cells arrested at the G2/M phase (Fig. 4C, E). The presence of 3-DZNeP inhibited TGF-β1–induced phosphorylation of H3Ser10. Similar to this observation, silencing of EZH2 with its siRNA reduced TGF-β1–induced phosphorylation of H3Ser10 (Fig. 4D, F). The data illustrate that EZH2 inhibition suppresses renal cell arrest in kidneys with obstruction injury and renal TECs exposed to TGF-β1.

EZH2 inhibition suppresses expression of Snail-1 and Twist in mice with obstruction injury and TGF-β1–induced renal TECs

Snail-1 and Twist are 2 transcription factors that are critically involved in the repression of the epithelial phenotype and activation of the mesenchymal phenotype after fibrotic injury (7). To investigate the mechanism by which EZH2 mediates their involvement in renal EMT, we examined the effect of 3-DZNeP on the expressions of Snail-1 and Twist in a murine model of renal fibrosis induced by UUO. Our immunoblot analysis results showed that UUO injury induced a dramatic increase in the expression of Snail-1 and Twist at d 14. Administration of 3-DZNeP strongly inhibited expression levels of Snail-1 (∼60%) and Twist (∼50%) (Fig. 5A–C). Immunofluorescent staining showed that both Snail-1 and Twist were highly expressed in the nucleus and cytosol of renal TECs and interstitial cells in the injured kidney. Their expression in renal tubules was also demonstrated by costaining with Vimentin (Fig. 5D, E).

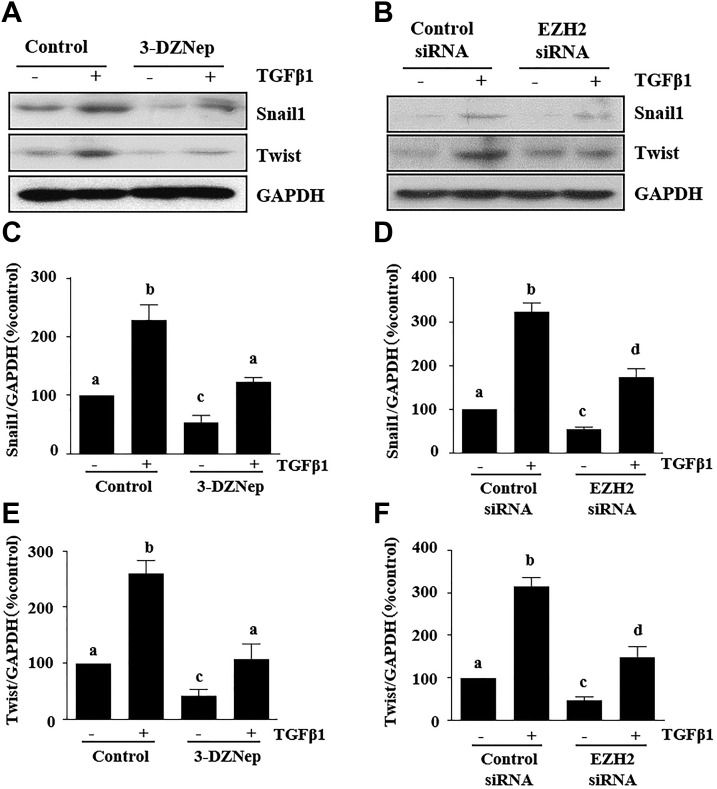

To further evaluate the role of EZH2 in the expression of Snail-1 and Twist, we examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on the expression of Snail-1 and Twist in cultured renal TECs exposed to TGF-β1. Incubation of serum-starved TKPT cells with 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 resulted in increased expression of Snail-1 and Twist. This response was abolished by 3-DZNeP (Fig. 6A, C, E). In addition, silencing of EZH2 with its specific siRNA also completed inhibited TGF-β1–induced expression of both Snail-1 and Twist (Fig. 6B, D, F).

Figure 6.

EZH2 inhibition suppresses the expressions of Snail1 and Twist in TGF-β1–induced proximal TECs. A, B) TKPT cells were serum starved for 24 h and treated with 3-DZNeP (10 µM) for 1 h (A) or transfected with EZH2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 24 h (B) followed by exposure of cells to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis with antibodies against Snail-1, Twist, and GAPDH. C–F) All proteins were quantified by densitometry and were normalized to GAPDH. Data were means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

These data suggest that EZH2 acts as an EMT regulator through activation of Snail-1 and Twist in the fibrotic kidney.

EZH2 inhibition diminishes UUO-induced PTEN down-regulation and AKT phosphorylation in mice with obstruction injury and TGF-β1–induced renal TECs

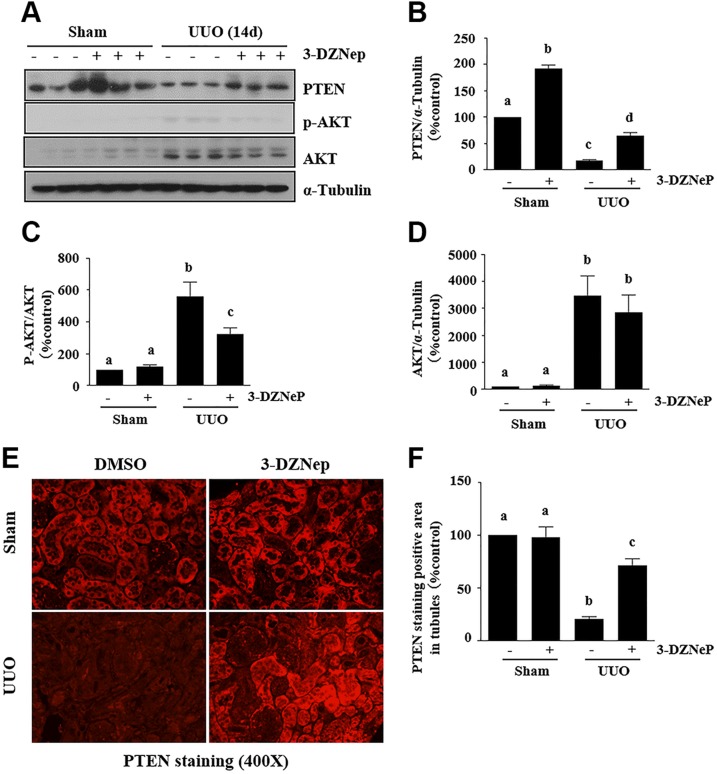

PTEN attenuates activation of downstream signaling molecules of PI3K (29) and negatively regulates EMT through antagonism of the PI3K/AKT pathway (30). We hypothesize that EZH2 also contributes to EMT by modulating expression of PTEN and subsequent inhibition of its downstream signaling pathways. We examined the effect of 3-DZNeP on the expression of renal PTEN and phosphorylation of AKT in the murine model of renal fibrosis induced by UUO and cultured renal proximal tubular cells. UUO injured kidney displayed decreased expression of PTEN and increased phosphorylation of AKT whereas administration of 3-DZNeP limited PTEN expression levels to a certain level (∼60% of total) in the injured kidney, which was accompanied by decreased expression of phosphorylated AKT (Fig. 7A–D). In agreement with the results, immunofluorescent staining also showed that PTEN was abundantly expressed in the cytosol of renal TECs in the control kidneys and diminished in the kidney with ureteral obstruction. 3-DZNeP increased the abundance of PTEN in the control kidney and partially restored its expression in UUO-injured kidneys (Fig. 7E, F).

Figure 7.

EZH2 inhibition reversed the low level of PTEN and phosphorylation of AKT increase in obstructed kidneys. A) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against PTEN, p-AKT, AKT, and α-tubulin. B–D) Expression levels of PTEN, p-AKT, AKT, and α-tubulin were quantified by densitometry, and PTEN (B) and AKT (D) were normalized with α-tubulin, and p-AKT (C) was normalized with AKT. E) Photomicrographs illustrate PTEN staining in the obstructed kidney. F) Photomicrographs illustrate PTEN+ area in the obstructed kidney. The values are means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

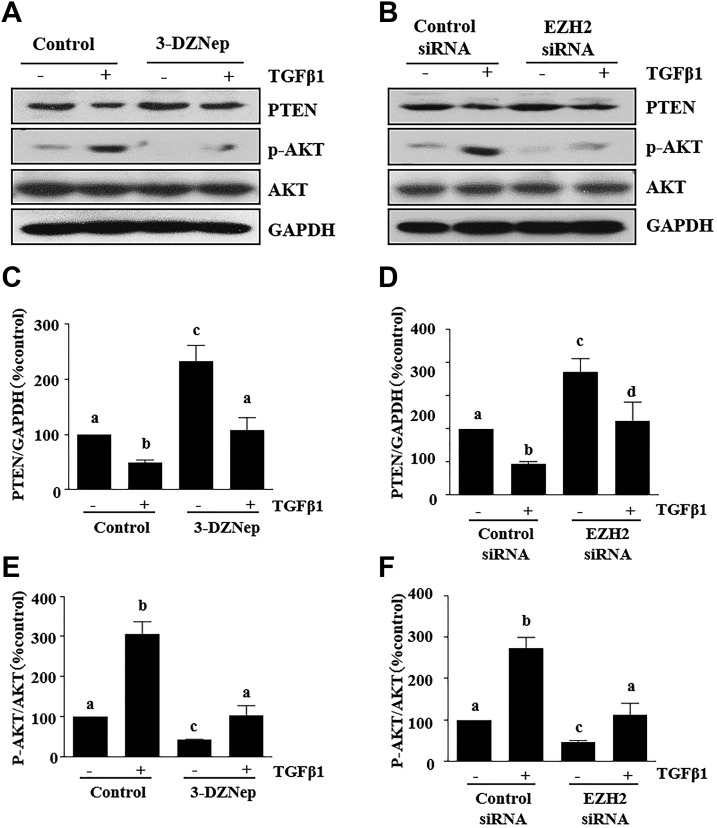

We further examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on PTEN expression and AKT phosphorylation induced by TGF-β1 in cultured renal TECs. For this purpose, TKPT cells were serum starved for 24 h and then exposed to 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 in the absence or presence of 3-DZNeP. TGF-β1 treatment markedly decreased the expressions of PTEN and increased the phosphorylation of AKT, and treatment of TKPT with 3-DZNeP inhibited TGF-β1-induced PTEN loss and AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 8A, C, E). Silencing EZH2 with siRNA also reversed the effect of TGF-β1-stimuated PTEN down-regulation and AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 8B, D, F).

Figure 8.

EZH2 inhibition reversed the low level of PTEN and phosphorylation of AKT in TGF-β1–induced proximal TECs. A, B) TKPT cells were serum starved for 24 h and then treated with 3-DZNeP (10 µM) for 1 h (A) or transfected with EZH2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 24 h (B) followed by exposure of cells to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis with antibodies against PTEN, p-AKT, AKT, and GAPDH. C–F) All proteins were quantified by densitometry, PTEN was normalized to α-tubulin, and p-AKT was normalized to AKT. Values are means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

These data suggest that PTEN mediates EZH2-induced down-regulation and activation of the AKT signaling pathway during the process of renal EMT.

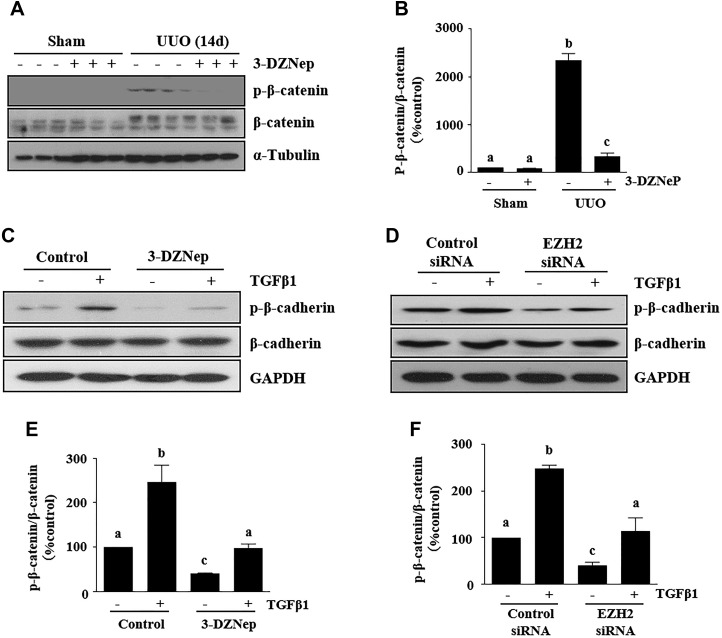

EZH2 inhibition suppresses β-catenin signaling in mice with UUO injury and TGF-β1–induced renal TECs

Activation of β-catenin plays an important role in the induction of EMT and inhibition of it attenuates renal fibrosis (31). To understand whether EZH2 regulates the β-catenin signaling pathway, we examined the effect of 3-DZNeP on the phosphorylation of β-catenin at serine 33, 37, or 41 in a murine model of renal fibrosis induced by UUO and cultured renal epithelial cells. Total β-catenin, but not its phosphorylated form, was detected in the sham-operation kidney; UUO injury increased expression of total β-catenin and induced phosphorylation of β-catenin, whereas administration of 3-DZNeP abolished β-catenin phosphorylation without affecting expression of total β-catenin levels (Fig. 9A, B). In cultured renal epithelial cells, total β-catenin was highly expressed, and a basal level of phosphorylated β-catenin was also detected. Presence of 3-DZNeP resulted in decreased expression of phosphorylated β-catenin, but expression of total β-catenin was not affected. We observed similar results in renal epithelial cells transfected with EZH2 siRNA (Fig. 9C–F). These data indicate that β-catenin signaling is also subject to regulation by EZH2 and suggest that EZH2 may also induce EMT through activation of β-catenin signaling.

Figure 9.

EZH2 inhibition suppresses β-catenin signaling in obstructed kidneys and TGF-β1–induced proximal TECs. A) Kidney tissue lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies against p-β-catenin, β-catenin, and α-tubulin. B) Expression levels of p-β-catenin and β-catenin were quantified by densitometry and were normalized with β-catenin. C, D) TKPT cells were serum starved for 24 h and treated with 3-DZNeP (10 µM) for 1 h (C) or transfected with EZH2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA for 24 h (D) followed by exposure of cells to TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) for an additional 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis with antibodies against p-β-catenin, β-catenin, and GAPDH. p-β-Catenin and β-catenin were quantified by densitometry and normalized to β-catenin (E, F). Values are means ± sd (n = 6). Different letters (a–d) indicate significantly different results. P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Although numerous studies have pointed to the importance of injured TECs in the development and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD), the contribution of an EMT undergone by renal epithelial cells during kidney fibrosis is still debated (9, 27, 32). Recent studies have demonstrated that kidney tubular cells undergo partial EMT after injury and rest at G2/M phase of cell cycles, a profibrotic phenotype that overproduces the profibrotic factors and cytokines to stimulate activation of renal interstitial fibroblasts and interstitial fibrosis (7, 9). Although this finding provides interesting insight into the mechanism of renal fibrosis after injury, the regulatory mechanism responsible for partial EMT in the kidney remains obscure. In this study, we demonstrated that pharmacological blockage of EZH2 with 3-DZNeP inhibits partial EMT and G2/M arrest of renal epithelial cells in a murine model of renal fibrosis induced by UUO. 3-DZNeP treatment or siRNA-mediated silencing of EZH2 also suppresses those events in cultured renal tubule epithelial cells exposed to TGF-β1. Moreover, EZH2 inhibition suppressed expressions of Snail-1 and Twist and reduced activation of AKT and β-actin signaling pathways associated with renal EMT. Thus, we have identified EZH2 as an important epigenetic regulator of renal EMT and suggested that it could be a novel target for therapeutic interference in renal fibrosis.

An early event in EMT involves down-regulation of E-cadherin, a major component of adherens junctions (33). The cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin forms a complex with β-catenin and other proteins at the plasma membrane. Proteolytic shedding of the E-cadherin ectodomain results in the release of β-catenin followed by its translocation from the plasma membrane to the nucleus, whereas β-catenin induces Slug, repressing transcription of E-cadherin and inducing EMT (34). Vimentin is another marker for EMT, which is not expressed in mature and polarized renal tubular cells, but is re-expressed in injured tubular cells (35–37). In this study, we observed that UUO injury to the kidney reduced E-cadherin expression and increased vimentin expression, whereas treatment with the EZH2 inhibitor preserved E-cadherin expression and decreased expression of Vimentin in the kidney, suggesting that EZH2 is an important regulator of renal EMT after fibrotic injury. In support of this hypothesis, we further demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of EZH2 blocks TGF-β1-stimualted E-cadherin down-regulation and Vimentin up-regulation in cultured renal epithelial cells and inhibits their morphologic changes. It appears that EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 directly binds to E-cadherin and inhibits its expression, given that H3K27me3 forms a repressive chromatin structure, leading to suppressed rather increased gene expression (20, 21).

The functional consequence of renal EMT after severe injury is the arrest of cell cycle at the G2/M phase (4, 7). This population of epithelial cells represents a profibrotic phenotype that undergoes maladaptive repair and acquires the ability to produce a large amount of growth factors and cytokines that stimulate renal fibroblast activation and accumulation of ECM proteins. In line with our demonstration that EZH2 inhibition suppressed the EMT program, 3-DZNep was also effective in inhibiting the arrest of renal tubular cells at the G2/M phase in the kidney injured by UUO and TECs exposed to TGF-β1. It has been reported that epithelial cells arrested at the G2/M phase are also able to activate some signaling pathways, such as JNK, that increase profibrotic cytokine production. Further studies are needed to address the role of EZH2 in the regulation of this and other signaling pathways.

The reactivation of Snail-1 and Twist in mouse renal epithelial cells has been shown to be essential for the development of fibrosis in the kidney (38, 39). Snail-1 is reactivated in mice that have been subjected to UUO (40, 41) and in fibrotic lesions obtained from patients who have undergone nephrectomy (42), suggesting that these transcription factors are key drivers of renal fibrogenesis after injury. On this basis, we examined the effect of EZH2 inhibition on the expression of Snail-1 and Twist in the kidneys after UUO injury and in cultured TECs stimulated with TGF-β1. Our results showed that pharmacological inhibition of EZH2 reduced expression of Snail-1 and Twist to the basal levels in both in vivo and in vitro models. Currently, the mechanism by which blocking EZH2 inhibits these 2 transcription factors is not clear. Since phosphorylation of Snail-1 and Twist can lead to their degradation by the proteasome (43, 44), it is likely that EZH2 regulates their expression through modulation of the components in the signaling pathways that leads to their phosphorylation. In this regard, Snail-l phosphorylation may be induced by the Wnt/β-catenin and AKT signaling pathways (45).

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is important to EMT regulation and has been suggested as a potential therapeutic target for fibrosis (46). Activation of β-catenin signaling is indispensable for proper nephron formation and kidney development (47, 48). Although it is relatively silent in the adult kidney, β-catenin signaling is clearly reactivated in a wide variety of fibrotic injuries leading to CKD such as obstructive nephropathy, diabetic nephropathy, doxorubicin nephropathy, polycystic kidney disease, and chronic allograft nephropathy (49–51). Our current results indicate that EZH2 activity is necessary for activation of β-catenin, which we demonstrated by showing that pharmacological inhibition or silencing of EZH2 with siRNA suppressed β-catenin phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo. The reduction of β-catenin phosphorylation upon EZH2 inhibition may also contribute to EMT inhibition, given that β-catenin functions as a component of adherens junctions and links E-cadherin to the cytoskeleton. Phosphorylation of β-catenin can promote its ubiquitination and degradation, resulting in loss of β-catenin/E-cadherin association and initiation of EMT program (52). In addition, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling leads to an increased level of Snail-1, which represses E-cadherin and promotes EMT. Thus, EZH2 inhibition-elicited Snail-1 down-regulation may be, at least in part, related to inhibition of β-catenin phosphorylation.

β-Catenin phosphorylation is regulated by the PI3K/Akt pathway. One the one hand, activated Akt phosphorylates serine at residue 552 in β-catenin, leading to an increase in its transcriptional activity (53). On the other hand, Akt can induce the phosphorylation of its substrate, glycogen synthase kinase-3β at the ninth residue, which facilitates the ubiquitination and degradation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β and subsequently increases intracellular β-catenin levels (54). Because PTEN is a major negative regulator of the PI3K/Akt signal pathway and blocking EZH2 with 3-DZNeP leads to increased expression of PTEN (23), EZH2 inhibition mediated up-regulation PTEN should suppress activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling. Indeed, we found that UUO injury to the kidney resulted in down-regulation of PTEN, whereas administration of 3-DZNeP restored PTEN expression, which was accompanied by decreased expression levels of phospho-AKT. Similarly, we observed that 3-DZNep treatment preserved PTEN levels and inhibited AKT phosphorylation in cultured renal epithelial cells undergoing EMT after TGF-β1 exposure. Thus, we suggest that EZH2-mediated down-regulation of PTEN plays a necessary role in renal EMT though inhibition of AKT. However, preservation of PTEN expression may not be the sole mechanism by which AKT is inactivated in the fibrotic kidney or renal epithelial cells undergoing EMT. A recent study showed that PI3K interacting protein-1, another negative regulator of PI3K (55), is also a direct substrate of EZH2 (56). EZH2 inhibition can up-regulate PI3K interacting protein-1 and contribute to cell death by inhibiting PI3K/AKT signaling in AT-rich interaction domain 1A (a chromatin remodeler)–mutated cells (56).

Increasing evidence indicates the importance of EZH2 in mediating tissue and organ fibrosis. EZH2 levels are elevated in the fibrotic liver, and genetic or pharmacologic disruption of this molecule can attenuate liver fibrogenesis by inhibiting fibrotic characteristics of myofibroblasts (57). EZH2-mediated histone hypermethylation has also been found to be involved in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (58). Although EZH2 is abundantly expressed in the developing kidney, its expression level is quickly decreased after birth. A dramatic increase in the expression of EZH2 was found in the injured kidney of mice after UUO. Given that the functional consequence of increased EZH2 correlates with metastasis and increased aggressiveness of most cancers (59), and a high level of EZH2 expression in the injured kidney and renal proximal TECs exposed to TGF-β1 is associated with EMT and renal fibroblast activation, targeting EZH2 may be a promising approach in the treatment of CKD.

In summary, this is the first study to demonstrate that EZH2 is a pivotal regulator of renal EMT in the fibrotic kidney. The anti-EMT actions of EZH2 blockade are associated with preservation of E-cadherin expression, inhibition of transcription factor activation, and inactivation of the PTEN/AKT and β-catenin signaling pathways. Because renal EMT and subsequent G2/M arrest are pivotal processes associated with overproduction of profibrotic cytokines and induction of renal fibrosis, EZH2 inhibitors would have therapeutic potential for treatment of renal fibrosis. Currently, several compounds for inhibition of EZH2 have been developed and are widely used in preclinical and in vitro studies to investigate the function of EZH2 in cancers and other diseases (60), and our data suggest a possible benefit from a clinical trial of treatment of renal fibrosis by EZH2 inhibition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Yingjie Guan (Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University) for critically reading and editing the article. This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants 5R01DK085065 and 1R01DK113256-01A1 (to S.Z.), and National Nature Science Foundation of China Grants 81270778 and 81470920 (to S.Z.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- 3-DZNeP

3-deazaneplanocin A

- AKT

protein kinase B

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- EZH2

enhancer of zeste homolog-2

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- H3K27me3

histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation

- H3pSer10

phospho-histone H3 at serine 10

- PAS

periodic acid Schiff

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- Snail-1

Snail family transcriptional repressor 1

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TEC

tubular epithelial cell

- TKPT

mouse kidney proximal tubular

- Twist-1

Twist family basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor 1

- UUO

unilateral ureteral obstruction

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X. Zhou, C. Xiong, and E. Tolbert performed the experiments and prepared the figures; T. C. Zhao helped to design and discuss the experiments; X. Zhou, G. Bayliss, and S. Zhuang prepared the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. (2013) Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis, 1: common and organ-specific mechanisms associated with tissue fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 304, C216–C225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.François H., Chatziantoniou C. (2017) Renal fibrosis: Recent translational aspects. [E-pub ahead of print] Matrix Biol.10.1016/j.matbio.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meng X. M., Nikolic-Paterson D. J., Lan H. Y. (2016) TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 12, 325–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang L., Besschetnova T. Y., Brooks C. R., Shah J. V., Bonventre J. V. (2010) Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat. Med. 16, 535–543, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canaud G., Bonventre J. V. (2015) Cell cycle arrest and the evolution of chronic kidney disease from acute kidney injury. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 30, 575–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grande M. T., Sánchez-Laorden B., López-Blau C., De Frutos C. A., Boutet A., Arévalo M., Rowe R. G., Weiss S. J., López-Novoa J. M., Nieto M. A. (2015) Snail1-induced partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition drives renal fibrosis in mice and can be targeted to reverse established disease. Nat. Med. 21, 989–997[correction Nat. Med. 22, 217] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovisa S., LeBleu V. S., Tampe B., Sugimoto H., Vadnagara K., Carstens J. L., Wu C. C., Hagos Y., Burckhardt B. C., Pentcheva-Hoang T., Nischal H., Allison J. P., Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. (2015) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition induces cell cycle arrest and parenchymal damage in renal fibrosis. Nat. Med. 21, 998–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBleu V. S., Taduri G., O’Connell J., Teng Y., Cooke V. G., Woda C., Sugimoto H., Kalluri R. (2013) Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nat. Med. 19, 1047–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovisa S., Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. (2016) Partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and other new mechanisms of kidney fibrosis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 681–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphreys B. D., Lin S. L., Kobayashi A., Hudson T. E., Nowlin B. T., Bonventre J. V., Valerius M. T., McMahon A. P., Duffield J. S. (2010) Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 85–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu W., Yang Z., Lu N. (2015) A new role for the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Adhes. Migr. 9, 317–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan A., Du J. (2015) Potential role of Akt signaling in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 30, 385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan R. J., Zhou D., Zhou L., Liu Y. (2014) Wnt/β-catenin signaling and kidney fibrosis. Kidney Int. Suppl. (2011) 4, 84–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tampe B., Zeisberg M. (2014) Evidence for the involvement of epigenetics in the progression of renal fibrogenesis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 29(Suppl 1), i1–i8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wing M. R., Ramezani A., Gill H. S., Devaney J. M., Raj D. S. (2013) Epigenetics of progression of chronic kidney disease: fact or fantasy? Semin. Nephrol. 33, 363–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu S., Zhang Y., Zhong S., Gao F., Chen Y., Li W., Zheng F., Shi G. (2017) N-n-butyl haloperidol iodide protects against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells by regulating the ROS/MAPK/Egr-1 pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 7, 520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wanner N., Bechtel-Walz W. (2017) Epigenetics of kidney disease. Cell Tissue Res. 369, 75–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewitson T. D., Holt S. G., Smith E. R. (2017) Progression of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and the chronic kidney disease phenotype: role of risk factors and epigenetics. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morey L., Helin K. (2010) Polycomb group protein-mediated repression of transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen H., Laird P. W. (2013) Interplay between the cancer genome and epigenome. Cell 153, 38–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagener N., Macher-Goeppinger S., Pritsch M., Hüsing J., Hoppe-Seyler K., Schirmacher P., Pfitzenmaier J., Haferkamp A., Hoppe-Seyler F., Hohenfellner M. (2010) Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) expression is an independent prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 10, 524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao R., Zhang Y. (2004) The functions of E(Z)/EZH2-mediated methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou X., Zang X., Ponnusamy M., Masucci M. V., Tolbert E., Gong R., Zhao T. C., Liu N., Bayliss G., Dworkin L. D., Zhuang S. (2016) Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 inhibition attenuates renal fibrosis by maintaining Smad7 and phosphatase and tensin homolog expression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 2092–2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pang M., Kothapally J., Mao H., Tolbert E., Ponnusamy M., Chin Y. E., Zhuang S. (2009) Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity attenuates renal fibroblast activation and interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 297, F996–F1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pang M., Ma L., Gong R., Tolbert E., Mao H., Ponnusamy M., Chin Y. E., Yan H., Dworkin L. D., Zhuang S. (2010) A novel STAT3 inhibitor, S3I-201, attenuates renal interstitial fibroblast activation and interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 78, 257–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krämer M., Dees C., Huang J., Schlottmann I., Palumbo-Zerr K., Zerr P., Gelse K., Beyer C., Distler A., Marquez V. E., Distler O., Schett G., Distler J. H. (2013) Inhibition of H3K27 histone trimethylation activates fibroblasts and induces fibrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 614–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carew R. M., Wang B., Kantharidis P. (2012) The role of EMT in renal fibrosis. Cell Tissue Res. 347, 103–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin X. L., Liu M., Liu Y., Hu H., Pan Y., Zou W., Fan X., Hu X. (2018) Transforming growth factor β1 promotes migration and invasion in HepG2 cells: Epithelial‑to‑mesenchymal transition via JAK/STAT3 signaling. Int. J. Mol. Med. 41, 129–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosivatz E. (2007) Inhibiting PTEN. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 257–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao Y., Wei H., Liu L., Liu L., Bai S., Li C., Luo Y., Zeng R., Han M., Ge S., Xu G. (2011) Upregulated DJ-1 promotes renal tubular EMT by suppressing cytoplasmic PTEN expression and Akt activation. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog. Med. Sci. 31, 469–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin W., Chung A. C., Huang X. R., Meng X. M., Hui D. S., Yu C. M., Sung J. J., Lan H. Y. (2011) TGF-β/Smad3 signaling promotes renal fibrosis by inhibiting miR-29. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 1462–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galichon P., Finianos S., Hertig A. (2013) EMT-MET in renal disease: should we curb our enthusiasm? Cancer Lett. 341, 24–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peinado H., Quintanilla M., Cano A. (2003) Transforming growth factor beta-1 induces snail transcription factor in epithelial cell lines: mechanisms for epithelial mesenchymal transitions. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21113–21123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng G., Lyons J. G., Tan T. K., Wang Y., Hsu T. T., Min D., Succar L., Rangan G. K., Hu M., Henderson B. R., Alexander S. I., Harris D. C. (2009) Disruption of E-cadherin by matrix metalloproteinase directly mediates epithelial-mesenchymal transition downstream of transforming growth factor-beta1 in renal tubular epithelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 175, 580–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Hir M., Hegyi I., Cueni-Loffing D., Loffing J., Kaissling B. (2005) Characterization of renal interstitial fibroblast-specific protein 1/S100A4-positive cells in healthy and inflamed rodent kidneys. Histochem. Cell Biol. 123, 335–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witzgall R., Brown D., Schwarz C., Bonventre J. V. (1994) Localization of proliferating cell nuclear antigen, vimentin, c-Fos, and clusterin in the postischemic kidney: evidence for a heterogenous genetic response among nephron segments, and a large pool of mitotically active and dedifferentiated cells. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 2175–2188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu M. Q., De Broe M. E., Nouwen E. J. (1996) Vimentin expression and distal tubular damage in the rat kidney. Exp. Nephrol. 4, 172–183 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamouille S., Xu J., Derynck R. (2014) Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 178–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poesen R., Viaene L., Verbeke K., Claes K., Bammens B., Sprangers B., Naesens M., Vanrenterghem Y., Kuypers D., Evenepoel P., Meijers B. (2013) Renal clearance and intestinal generation of p-cresyl sulfate and indoxyl sulfate in CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8, 1508–1514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato M., Muragaki Y., Saika S., Roberts A. B., Ooshima A. (2003) Targeted disruption of TGF-beta1/Smad3 signaling protects against renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1486–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grande M. T., Fuentes-Calvo I., Arévalo M., Heredia F., Santos E., Martínez-Salgado C., Rodríguez-Puyol D., Nieto M. A., López-Novoa J. M. (2010) Deletion of H-Ras decreases renal fibrosis and myofibroblast activation following ureteral obstruction in mice. Kidney Int. 77, 509–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boutet A., De Frutos C. A., Maxwell P. H., Mayol M. J., Romero J., Nieto M. A. (2006) Snail activation disrupts tissue homeostasis and induces fibrosis in the adult kidney. EMBO J. 25, 5603–5613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang H., Massi D., Hemmings B. A., Mandalà M., Hu Z., Wicki A., Xue G. (2016) AKT-ions with a TWIST between EMT and MET. Oncotarget 7, 62767–62777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serrano-Gomez S. J., Maziveyi M., Alahari S. K. (2016) Regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition through epigenetic and post-translational modifications. Mol. Cancer 15, 18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong K. O., Kim J. H., Hong J. S., Yoon H. J., Lee J. I., Hong S. P., Hong S. D. (2009) Inhibition of Akt activity induces the mesenchymal-to-epithelial reverting transition with restoring E-cadherin expression in KB and KOSCC-25B oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y. (2010) New insights into epithelial-mesenchymal transition in kidney fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 212–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt-Ott K. M., Barasch J. (2008) WNT/beta-catenin signaling in nephron progenitors and their epithelial progeny. Kidney Int. 74, 1004–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iglesias D. M., Hueber P. A., Chu L., Campbell R., Patenaude A. M., Dziarmaga A. J., Quinlan J., Mohamed O., Dufort D., Goodyer P. R. (2007) Canonical WNT signaling during kidney development. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 293, F494–F500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He W., Kang Y. S., Dai C., Liu Y. (2011) Blockade of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by paricalcitol ameliorates proteinuria and kidney injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 90–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dai C., Stolz D. B., Kiss L. P., Monga S. P., Holzman L. B., Liu Y. (2009) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling promotes podocyte dysfunction and albuminuria. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 1997–2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Surendran K., Schiavi S., Hruska K. A. (2005) Wnt-dependent beta-catenin signaling is activated after unilateral ureteral obstruction, and recombinant secreted frizzled-related protein 4 alters the progression of renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 2373–2384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vu T., Datta P. K. (2017) Regulation of EMT in colorectal cancer: a culprit in metastasis. Cancers (Basel) 9, 171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chowdhury M. K., Montgomery M. K., Morris M. J., Cognard E., Shepherd P. R., Smith G. C. (2015) Glucagon phosphorylates serine 552 of β-catenin leading to increased expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc in the isolated rat liver. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 121, 88–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qiao M., Sheng S., Pardee A. B. (2008) Metastasis and AKT activation. Cell Cycle 7, 2991–2996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He X., Zhu Z., Johnson C., Stoops J., Eaker A. E., Bowen W., DeFrances M. C. (2008) PIK3IP1, a negative regulator of PI3K, suppresses the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 68, 5591–5598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bitler B. G., Aird K. M., Garipov A., Li H., Amatangelo M., Kossenkov A. V., Schultz D. C., Liu Q., Shih IeM., Conejo-Garcia J. R., Speicher D. W., Zhang R. (2015) Synthetic lethality by targeting EZH2 methyltransferase activity in ARID1A-mutated cancers. Nat. Med. 21, 231–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Atta H., El-Rehany M., Hammam O., Abdel-Ghany H., Ramzy M., Roderfeld M., Roeb E., Al-Hendy A., Raheim S. A., Allam H., Marey H. (2014) Mutant MMP-9 and HGF gene transfer enhance resolution of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats: role of ASH1 and EZH2 methyltransferases repression. PLoS One 9, e112384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coward W. R., Feghali-Bostwick C. A., Jenkins G., Knox A. J., Pang L. (2014) A central role for G9a and EZH2 in the epigenetic silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. FASEB J. 28, 3183–3196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deb G., Singh A. K., Gupta S. (2014) EZH2: not EZHY (easy) to deal. Mol. Cancer Res. 12, 639–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hibino S., Saito Y., Muramatsu T., Otani A., Kasai Y., Kimura M., Saito H. (2014) Inhibitors of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) activate tumor-suppressor microRNAs in human cancer cells. Oncogenesis 3, e104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]