Abstract

The Lancet’s 1998 publication of “Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children” by Andrew Wakefield, et. al., positing a causal relationship between MMR vaccine and autism in children, set off a media storm and galvanized the anti-vaccine movement. In this paper, centuries-old fears of vaccination and the history of autism as a medical diagnosis are considered, and an affective, family-centered approach to dealing with parental fears by physicians is proposed.

Introduction

A three-month-old girl was admitted onto the pediatric clinic medicine service of a university-affiliated children’s hospital in the winter of 2008 with a three to four day history of worsening cough and fever leading to decreased oral intake. She had been brought to the emergency room by her parents and was observed to have paroxysms of cough and had a SpO2 on room air which would drop into the 70s during these episodes. Family history was significant for a teenage brother who had suffered a recent persistent cough for a few weeks but had experienced no fever. Despite her age, the baby had not received any immunizations on the advice of the family’s chiropractor. The family also said that they had “read some stuff on the Internet about shots and autism,” and they felt the baby would be better off not getting immunizations than “taking a chance” that vaccines might harm her. The baby’s nasopharyngeal swab was positive for pertussis, as was her follow-up culture. She required oxygen by nasal cannula for five days and was sent home after she was weaned to room air. The parents were counseled that the baby would likely still have a cough for many weeks to come.

This was one of three pertussis cases seen by the clinic medicine attending during one month on inpatient service, the first time in his career that he had seen more than one patient admitted for pertussis within a month.

On the Rise

He was not alone. In 2008, in the state of Missouri, there were 561 cases of pertussis reported to the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. Pertussis had been on the decline for the previous two years (308 cases in 2006, and 118 in 2007). The 561 Missouri pertussis cases represented an 82% increase over the five-year median of 308 cases. In addition, the number of reported pertussis outbreaks in Missouri also increased in 2008, from two reported in 2007 to 11 in 2008.1

Elsewhere, things have been even worse. In 2010, 9,120 cases of pertussis were reported to the California Department of Public Health for a state rate of 23.3 cases/100,000. This is the most cases reported in California in 63 years, when 9,394 cases were reported in 1947, and the highest incidence in 52 years, when a rate of 26.0 cases/100,000 was reported in 1958. Of the 9,120 cases, 804 (9%) were hospitalized. Four hundred and forty-two (55%) of hospitalized cases were infants <3 months of age, and 581 (72%) were infants <6 months of age. Ten deaths were reported. Nine fatalities were infants <2 months of age at time of disease onset who had not received any doses of pertussis-containing vaccine. The tenth infant was an ex-28-week preemie who was two months of age and had received the first dose of DTaP only 15 days prior to disease onset (California DOPH website).

Unfortunately, pertussis is not the only vaccine-preventable disease to be enjoying a resurgence. Nationally, the reported incidence of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease has more than doubled from 0.48 cases/100,000 to 0.99/100,000 between 1999 and 2009, and the number of reported cases (all ages, serotypes) rose from 1,174 to 1,597 cases between 1994 and 2001.2

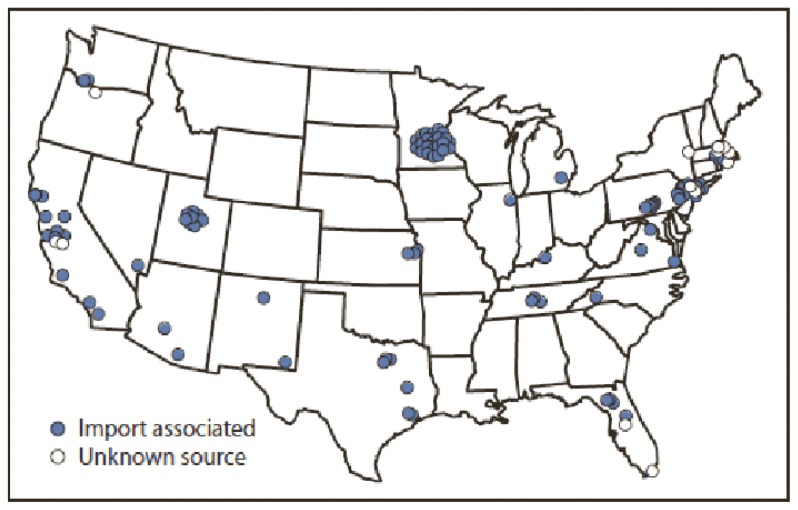

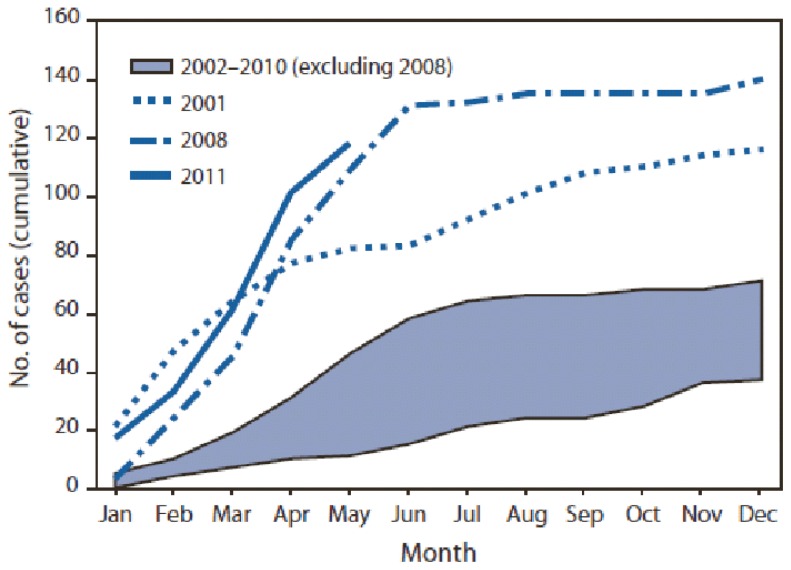

Furthermore, measles, which had been eliminated (defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as the absence of endemic transmission) in the United States in the late 1990s and likely in the rest of the Americas since the early 2000s, had 118 cases reported in the United States during the first 19 weeks of 2011, the highest number of reported measles cases for this period since 1996. (During 2001–2008, a median of 56 measles cases were reported to the CDC annually.) Of the 118 cases, 105 (89%) were associated with importation from other countries, and 105 (89%) patients were unvaccinated. Forty-seven (40%) patients were hospitalized, and nine had pneumonia. The largest outbreak occurred among 21 persons in a Minnesota population in which many children were unvaccinated because of parental concerns about the safety of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. That outbreak resulted in exposure to many persons and infection of at least seven infants too young to receive MMR vaccine.3 (See Figures 1 and 2.)

Figure 1.

Distribution and origin of reported measles cases (N = 118) --- United States, January 1--May 20, 2011, The figure above shows the distribution and origin of reported measles cases (N = 118) in the United States during January 1-May 20, 2011.

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines

Figure 2.

Cumulative number of measles cases reported, by month of rash onset --- United States, 2001--2011, The figure above shows the cumulative number of measles cases reported, by month of rash onset, in the United States during 2001–2011. During January 1-May 20, 2011, a total of 118 cases were reported, the highest number reported for the same period since 1996.

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines

In August 2005, a five-year-old boy with autism died in a physician’s office while receiving IV chelation therapy with Na2EDTA instead of CaNa2EDTA. The medical examiner report listed the cause of death as “diffuse, acute cerebral hypoxic-ischemic injury, secondary to diffuse subendocardial necrosis” likely due to the severe hypocalcemia. The case was investigated by the Pennsylvania State Board of Medicine (MMWR March 3, 2006), and it was clear that the hypocalcemia resulted from the inappropriate use of Na2EDTA.4

So what is going on? Why is childhood vaccination, which has reduced morbidity and mortality by margins unimaginable a century ago, being rejected by so many parents, and how have physicians and public health professionals failed to make the case for immunization? The purpose of this paper is to examine some of these issues around vaccination and how we, as medical and public health professionals, can more effectively and compassionately respond to parental concerns, both in the public sphere and in our one-to-one office encounters.

The Unnatural Act of Vaccination

While it is easy to view Andrew Wakefield’s 1998 paper, “Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children,” in The Lancet5 as the cause of the modern anti-vaccine movement, it may more accurately be viewed as giving already skeptical parents a “scientific” excuse to indulge in popular and centuries-old misgivings about the very idea of vaccination in the public mind.

In his essential 2011 book, The Panic Virus, journalist Seth Mnookin, writes, “it’s remarkable how static the makeup, rhetoric, and tactics of vaccine opponents have remained over the past 150 years. Then, as now, anti-vaccination forces fed on anxiety about the individual’s fate in industrialized societies; then, as now, they appealed to knee-jerk populism by conjuring up an imaginary elite with an insatiable hunger for control; then, as now, they preached the superiority of subjective beliefs over objective proofs, of knowledge acquired by personal experience rather than through scientific rigor.”6

Happily, the fact that vaccines have been spectacularly successful at drastically reducing the incidence of diseases like measles, polio, and pertussis, has meant that generations of parents have grown up without the specter of childhood death due to infectious disease. In the eighteenth century, before Jenner developed the cowpox-based vaccine for smallpox, the deadliest and most feared disease of the time, smallpox inoculation was introduced to Europe, probably from China, and involved lancing open a wound in the skin of an uninfected person and implanting scabs or fresh pus from a smallpox sufferer into these wounds. The inoculated person would usually develop a milder form of the disease and develop lifelong immunity, but death after inoculation was not uncommon. In March 1730, Benjamin Franklin reported in his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, that, of 72 Bostonians recently inoculated with smallpox, only two died while “the rest have recovered perfect health… Of those who had [smallpox] in the common way, ‘tis computed that one in four died.” These inoculation-associated deaths would be acceptable to a populace sadly and intimately familiar with a deadly disease, but in a society where these diseases have become relatively uncommon – and where, in fact, a large percentage of doctors have not even seen actual cases of many vaccine-preventable infectious diseases – parents may reasonably feel that delaying or even refusing vaccination for their children makes sense. Vaccines may very well be victims of their own success.

Yet even when the public does know the ravages of disease, unease about inoculation and vaccination is not uncommon. Because inoculation with smallpox did sometimes lead to death, it was railed against as an affront to the Sixth Commandment, “Thou shalt not kill.” And in 1802, a political cartoon was published showing people developing horns and hooves as a result of receiving Edward Jenner’s cowpox-derived vaccine.

Unfortunately, in the history of immunization – and of medicine in general – there are myriad examples of morbidity and mortality resulting from vaccination and scientific experimentation that have been passed down to parents already uneasy about the idea of subjecting their children to multiple painful injections.

In the fall of 1901, for example, 13 schoolchildren in St. Louis, Missouri, died of tetanus after they were treated with the diphtheria antitoxin. This occurred almost simultaneously with the deaths of nine schoolchildren in Camden, New Jersey, which were associated with a commercial vaccine allegedly tainted with tetanus. These deaths led Congress to enact the Biologics Control Act of 1902, establishing the first federal regulation of the vaccine industry, but the damage had already been done in the public mind.7

In early 1976 the Ford administration spearheaded a crash vaccine program when it was feared that a strain of flu similar to the 1918 pandemic strain would be appearing the following flu season. This became known in the press as Swine Flu, and the government rolled out its vaccine on October 1. While no one became sick with the feared strain of flu, by the end of November over 500 of 40,000,000 vaccine recipients had developed Guillan-Barre Syndrome, a rate seven times greater than expected for the population. Though alarming, these numbers did not reach a level of statistical significance and causality was never established. Nevertheless, in a hail of negative press, the program was halted on December 16, 1976.6

Meanwhile, in the mid-to late-1970s concerns were being raised about pertussis vaccine, particularly about purported neurological problems suffered by children after receiving the vaccine. While doctors were aware that children frequently had high fevers, febrile seizures, and extreme irritability after receiving the diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT) vaccine, there had never been any evidence that the vaccine caused any long-term sequelae. Nevertheless, the press began to pick up on this fear, and a turning point came with the airing of a television special called, “DPT: Vaccine Roulette,” in 1982. The program, originally shown locally in Washington, DC, but picked up by stations throughout the US, became a rallying cry for burgeoning anti-vaccine forces with its heart-wrenching depictions of children suffering from brain damage, seizures, and mental retardation, purportedly as a result of receiving DPT vaccine.

In late 1998 and into 1999, a provision of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Modernization Act of 1997 which required a federal report on levels of mercury in drugs and food was approaching the end of its two-year reporting timeframe. Thiomerosal, an ethylmercury compound that had been approved for use as an anticontaminant in vaccines in the 1940s, came under scrutiny. From a toxicology perspective mercury has long held a position of prominence as a heavy metal toxicant. The environmental disaster of Minamata Bay, Japan, in the 1950s, resulted from the release of highly toxic methyl mercury into Minamata Bay in Kumamato Prefecture, and images of neurodevastated children in Life magazine loomed large in the public imagination for decades. (See Sidebar, page 14).

Beyond general misgivings about vaccination, specific populations also feel they have reason to mistrust the medical profession. In particular, the notorious Tuskegee syphilis experiments stand out in the consciousness of the African-American and contributed to some mothers’ worries about vaccine safety. According to one mother: “[Tuskegee] always sticks in my mind. That you really don’t know what’s happening and here these people were guinea pigs and just don’t want my children to be part of that.”9

Autism, Parents, the DSM, and Doctors

Though child psychiatrist Leo Kanner first coined the term “Autism” in his 1943 paper “Autistic disturbances of affective conduct,” in which he described children with an inability to form normal human attachments, an extreme lack of empathy, and a tendency to get unnaturally absorbed in routine tasks, it wasn’t until his 1949 paper, “Problems of nosology and psychodynamics in early childhood autism,” that he discussed his observations of the parents of autistic children. He observed that “aside from the indisputably high level of intelligence, the vast majority of the parents of the autistic children have features in common which it would be impossible to disregard… Most of the parents declare outright that they are not comfortable in the company of people...” Furthermore, “The parents’ behaviour toward the children must be seen to be believed. Maternal lack of genuine warmth is often conspicuous in the first visit to the clinic.” Kanner concludes that the parents “themselves had been reared sternly in emotional refrigerators.”9

In the 1950s Bruno Bettelhiem, whose “status as a pioneering medical doctor, his academic bona fides, and his media savvy gave his opinions more weight than those of Kanner,”6 took this observation a step further, from Kanner’s non-judgmental descriptions which did not imply an etiology for autism, to the dreaded “refrigerator mothers,” harridans who emotionally isolated their children and cut them off from nurturing human contact.11 According to his biographer, Richard Pollak, “No prominent psychotherapist of this time was more antagonistic to mothers—in private and in public—as [Bettelheim] was, insisting that they caused autism by rejecting their infants and comparing them to devouring witches and the SS guards in the concentration camps.”12 As ludicrous as this seems from today’s perspective, “[t]he readiness with which Bettleheim’s theories were embraced illustrates how what are thought of as indisputable, evidence-based conclusions are influenced by prevailing social and cultural norms.”6

For decades then, parents, devastated by their child’s descent into a non-verbal state of repetitive self-stimulatory activity, desperately seeking answers, causes, and hope would be met by physicians who, with the best of intentions, would tell them, “Well, we don’t know what causes autism, but we think it was something you did.”

In 1952 the American Psychiatric Association published the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a compendium of standard criteria for the classification of mental disorders. In this first iteration, autism is not mentioned as a separate diagnosis or syndrome but as a descriptor under “schizophrenic reaction, childhood type,” which included “psychotic reactions in children, manifesting primarily as autism” as one of its symptoms. The DSM-II, published in 1968, still included autism only as a symptom under childhood schizophrenia. “Infantile autism” did not become a free-standing diagnosis until the publication of the DSM-III in 1980. The definition was expanded in the 1987 DSM-IV, which changed the diagnosis to “autistic disorder.” In 1994 the larger class of “pervasive developmental disorders” was introduced to include autistic disorder, along with Rett’s disorder, Asperger’s disorder, childhood developmental disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified, (PDD-NOS), and all of which are considered autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Over the years, as diagnostic criteria for ASDs have been both broadened and refined, physicians and parents have each become more aware of the signs and symptoms of autistic disorder and related disorders which have steadily encompassed greater numbers of children. In 2007 the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that pediatricians observe for signs of autism at every well child visit, and that they perform screening with the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) at the 18-month and 24-month well child visits.13

So in the nearly seven decades since Kanner first described autism, doctors are increasingly able to screen for ASDs earlier and begin to offer parents at least a glimmer of hope with early intervention programs. Still, many parents continued to live with blame, guilt, and isolation, all the while caring for difficult, frustrating children. These parents needed someone to give them hope, both that there might be a way to at least partially restore their children to health and to give them answers for what went wrong in the first place. In 1998, they finally found their savior, and his message was all the more satisfying for taking the burden of guilt for their child’s autism off of their shoulders and placing it on those who had blamed and shamed them for their child’s illness for so long – their doctors.

Enter Andrew Wakefield

“Rubella virus is associated with autism, and the combined measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (rather than the monovalent measles vaccine) has also been implicated.” With that sentence in the discussion section of his paper, “Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children,” in The Lancet,5 Andrew Wakefield and his 11 co-authors set off a furor over vaccination that has yet to abate.

The study purported to be a case series which established a link between the gastrointestinal difficulties and cognitive and behavioral deficits of a series of 12 children in the UK. According to the article, “Onset of behavioural symptoms was associated, by the parents, with measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination in eight of the 12 children, with measles infection in one child, and with otitis media in another… In these eight children [in whom the combination MMR vaccine was implicated] the average onset from exposure to first behavioural symptoms was 6.3 days (range 1–14).”5

Seth Mnookin describes the scene at the London news conference where Wakefield first appeared to discuss his paper. “Knowing that the paper’s findings would be controversial from the beginning, the five experts who addressed the media had agreed beforehand that regardless of their individual interpretations, they’d deliver one overarching message: Further research needed to be done before any conclusions could be drawn, and in the meantime, children should continue to receive the MMR vaccine. Once the tape recorders began to roll, however, Wakefield went dramatically off script. ‘With the debate that has been started, I cannot continue to support the continued use of the three vaccines together… My concerns are that one more case of this is too many and that we put children at no greater risk if we dissociated those vaccines into three…’ “6

The study was immediately and widely criticized, and within months, epidemiological studies were published that failed to find a link between MMR vaccine and autism, some of them in the pages of The Lancet14,15 Eventually, investigative reports by journalist Brian Deer in The Times (of London) in 2004 looking at Wakefield’s conflicts of interest in the 1998 paper led to a retraction by 10 of the 12 co-authors of the paper. According to the retraction, “no causal link was established between MMR vaccine and autism as the data were insufficient.” 16

Deer’s work in 2004 as well as in three subsequent investigative articles in the British Medical Journal 17 showed that:

♦ Wakefield had been hired in February 1996 at £150 an hour by a lawyer named Richard Barr who was working to bring a lawsuit against vaccine manufacturers.

♦ Wakefield filed an application for a patent for a “safer” single measles vaccine in the UK in June 1997.

♦ Patients included in the study were actively recruited from anti-MMR organizations, and the study was commissioned and funded for planned litigation.

♦ A study of the medical records of the 12 children in the study showed that despite the paper’s claim that all 12 children were “previously normal,” at least five had documented pre-existing developmental problems.

♦ In addition some of the children who were portrayed as having their first behavioral concerns within days of MMR vaccination did not in fact begin having symptoms until months later.

♦ Wakefield obtained blood samples for controls at his child’s birthday party, paying each child £5 for participating.

Eventually the UK’s General Medical Council (GMC) engaged in an unprecedented 217-day hearing between July 2007 and May 2010 on Wakefield’s fitness to practice. On May 24, 2010, they concluded, “Dr. Wakefield’s misconduct not only collectively amounts to serious professional misconduct, over a time frame from 1996 to 1999, but also, when considered individually, constitutes multiple separate instances of serious professional misconduct. Accordingly the Panel finds Dr. Wakefield guilty of serious professional misconduct,”18 and Wakefield had his license to practice medicine in the UK revoked.

Three months earlier, on February 2, 2010, The Lancet had quietly retracted Wakefield’s 1998 paper. 19

Case closed. One would think. But if anything, Wakefield’s decredentialing by the scientific and medical communities has turned him into a martyr, someone who is willing to give up everything for what he knows is right, a loner who refuses to be destroyed by those in power. Soon after the censures by the GMC, J. B. Handley, co-founder of Generation Rescue, a group that disputes vaccine safety, said, “To our community, Andrew Wakefield is Nelson Mandela and Jesus Christ rolled up into one… He’s a symbol of how all of us feel.”20

How did this happen, and why has the medical community let it happen?

The Power of Narrative

In the fall of 2009 as the CDC and the World Health Organization were warning of a pandemic caused by a new H1N1 flu strain, physicians were being asked, not just by patients but by the media, for their advice about vaccinating children. Unfortunately, in early news reports this new flu strain had been referred to as Swine Flu, and the rapid production of an H1N1 vaccine brought back uncomfortable associations with Gerald Ford’s ill-starred vaccination effort of 1976. The media sought out physicians to discuss the pros and cons of vaccination. In St. Louis, a weekly paper called the Ladue News, interviewed a local pediatrician for his opinion on vaccination. He was quoted as saying, “I tell parents that there is absolutely no data to support [a vaccine-autism link, and failure to vaccinate children is] foolish and dangerous. Immunization is safe and effective with minimal minor side effects. There is a small but real chance of complications, including fatal complications, with both the chicken pox vaccine, which can lead to pneumonia, encephalitis and hepatitis, and the influenza vaccine, which can develop into pneumonia or other secondary bacterial infections.”21

And Dr. Paul Offit, an infectious disease specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and one of the developers of a rotavirus vaccine, begins his book Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All with, “There’s a war going on out there… On one side are parents… On the other side are doctors… Caught in the middle are children.” 22

On the other hand, Wakefield says, “What happens to me doesn’t matter. What happens to these children does matter.”20 And Jenny McCarthy, actress, anti-vaccination stalwart, and president of Generation Rescue, writes on their website’s home page, “In profound solidarity with all the families still struggling, I decided to speak up. I wanted to give voice to options too often unspoken, and share hope for victories within reach. My family was given gifts that I wanted to share. Whether you’re in need at 3:00 p.m. or 3:00 a.m., you have come to the right place. We are here for you, together resolving our heartaches and celebrating our victories.”23

We in the medical community must acknowledge that, for parents, the idea of allowing their child to be injected with an agent that might cause harm and will definitely cause pain is, at the very least, unsettling to even the most educated, most rational parent. The genius of the anti-vaccine forces is that they are passionately empathetic toward parents who want only to protect their kids – and they are not shy about the sacrifices that they have personally made in standing up to uncaring physicians and greedy pharmaceutical companies.

And how do we respond? Often with a well-reasoned, evidence-based argument that dismisses vaccination concerns as unfounded and uninformed.

If we do express emotion about vaccination, it often comes across as either as anger at parents who just do not care enough to do what is best for their children or annoyance on our part for having to waste our time with such nonsense.

If You Were a Parent, Who Would You Trust?

As physicians, we do have our own stories and narratives, and we can use them to counter the fear-mongering of the vaccine deniers. We can tell of the sweat on our brow as we intubated a kid just seconds before her windpipe was sealed shut by hemophilus infection, or of the dread in our heart as we saw milky spinal fluid drip out of a lumbar puncture needle in a baby with pneumococcal infection, or of the mother who said she would never forgive herself if her child did not live because she listened to her chiropractor and did not have her baby immunized.

The science is clearly, unequivocally, powerfully on our side when it comes to the safety and effectiveness of vaccination, and we must share this information which is at the core of our efforts to prevent disease in children. But we have to remember that parents make decisions about their kids, not from the head, but from the heart.

In 1710 Jonathan Swift wrote,”Falsehood flies and the truth comes limping after; so that when men come to be undeceived, it is too late: the jest is over and the tale has had its effect.”

As such, we cannot be reticent to use our stories to let parents know that we do this work, that we vaccinate children because, as Andrew Wakefield himself said, “one more case of this is too many.” But in our case, “this” refers not to a self-serving fiction, but to pertussis, epiglottitis, and meningitis, to kids being devastated or killed by diseases that are completely preventable, to parents facing their fears with us beside them to give their children a better future.

Healing is about more than prescribing and instructing. It is also about listening, about saying that physicians were wrong to blame parents when we had no other explanation for autism, and sometimes just sitting in silence as we let parents know that it is okay if they are afraid and that we will walk through that fear with them.

Conclusion

As they were getting ready to go home from the hospital after five sleepless, nerve-wracking nights, the mother of the three-month-old girl with pertussis told the clinic med attending that, if he wanted to tell people about how sick her daughter was and what she and their entire family went through to help convince other parents to vaccinate their kids on time, it might give some meaning to their ordeal.

“Dr. Haller,” she said, “I don’t ever want any other family to have to suffer what we went through.”

Biography

Kenneth Haller, MD, FAAP, MSMA member since 2004, is Associate Professor of Pediatrics. Anthony J. Scalzo, MD, FAAP, FACMT, FAACT, is Professor of Pediatrics, Director, Division of Toxicology and Medical Director, Missouri Poison Center. Both are at Saint Louis University School of Medicine/SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center.

Contact: hallerka@slu.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.p. 34. http://health.mo.gov/living/healthcondiseases/communicable/communicabledisease/annual08/Annual08.pdf.

- 2.Summary of Notifiable Diseases - United States, 2009. Weekly. 2011 May 13;58(53):1–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Measles - United States, January-May 20, 2011. Weekly. 2011 May 27;60(20):666–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deaths Associated with Hypocalcemia from Chelation Therapy - Texas, Pennsylvania, and Oregon, 2003–2005. MMWR. 2006 Mar 3;55:204–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, Linnell J, Casson DM, Malik M, Berelowitz M, Dhillon AP, Thomson MA, Harvey P, Valentine A, Davies SE, Walker-Smith JA. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 1998 Feb 28;351(9103):637–41. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mnookin S. The Panic Virus: A True Story of Medicine, Science, and Fear. Simon & Schuster; Jan, 2011. p. 429. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willrich M. The New York Times. Jan 21, 2011. Why Parents Fear the Needle. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shui I, Kennedy A, Wooten K, Schwartz B, Gust D. Factors influencing African-American mothers’ concerns about immunization safety: a summary of focus group findings. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 May;97(5):657–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanner L. Problems of nosology and psychodynamics in early childhood autism. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1949;19(3):416–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1949.tb05441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badcock C. Kanner’s Curse: tarred with Bettelheim’s brush. The Imprinted Brain: Psychology Today blog. 2010 May 13; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollak R. The Creation of Dr. B: A Biography of Bruno Bettelheim. Simon & Schuster; 1997. pp. 21–22.pp. 478 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson Chris Plauché, MD, MEd, Myers Scott M, MD and the Council on Children With Disabilities. Identification and Evaluation of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. PEDIATRICS. 2007 Nov;120(5):1183–1215. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeStefano F, Chen RT. Negative association between MMR and autism. Lancet. 1999;353:1987–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor B, Miller E, Farrington CP, Petropoulos MC, Favot-Mayaud I, Li J, et al. Autism and measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine: No epidemiologic evidence for a causal association. Lancet. 1999;353:2026–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murch SH, Anthony A, Casson DH, Malik M, Berelowitz M, Dhillon AP, et al. Retraction of an interpretation. Lancet. 2004;363:750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15715-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deer B. How the case against the MMR vaccine was fixed. BMJ. 2011 Jan 5;342:c5347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Deer B. Secrets of the MMR scare: How the vaccine crisis was meant to make money. BMJ. 2011 Jan 11;342:c5258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Deer B. Secrets of the MMR scare. The Lancet’s two days to bury bad news. BMJ. 2011 Jan 18;342:c7001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GMC. Andrew Wakefield: determination on serious professional misconduct and sanction. May 24, 2010. www.gmc-uk.org/Wakefield_SPM_and_SANCTION.pdf_32595267.pdf.

- 19.Anonymous. Retraction-Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, nonspecific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet. 2010;375:445. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dominus S. The New York Times Magazine. Apr 20, 2011. The Crash and Burn of an Autism Guru. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ladue News, Vaccine Update: Shot or Not. Oct 29, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Offit P. Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All. Basic Books; 2011. p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- 23.http://www.generationrescue.org/home/profiles/jenny-mccarthy/