Abstract

Approximately 34 million family and friends provided unpaid care to individuals age 50 and older in 2015. It is difficult to place a value on that time, since there is no payment made to the caregiver, and multiplying the caregiving hours by a wage does not account for the value of lost leisure, the implications for future employability and wages, or any intrinsic benefits accrued to the care provider. This study uses a dynamic discrete choice model to estimate a more complete measure of the costs of informal care provided by a daughter to her mother, and compares these cost estimates across four categories of the mother’s functional status: has a doctor-diagnosed memory-related disease, limitations in activities of daily living (ADL), a combination of both, or cannot be left alone for an hour or more. We study adult women aged 40–70 with a living mother at the start of the sample period (N=3,427 women) using data from the Health and Retirement Study (1998–2012). The primary outcome is the monetized change in well-being due to caregiving, what economists call “welfare costs.” We estimate that the median cost to the daughter’s well-being of providing care to an elderly mother range from $144,302 to $201,896 over a two-year period, depending on the mother’s functional status. These estimates suggest that informal care cost $277 billion in 2011, 20 percent higher than estimates that only account for current foregone wages.

Keywords: memory-related disease, ADL limitations, costs of caregiving, informal care

INTRODUCTION

Informal care, unpaid care provided by family and friends, is a cornerstone of the care and support system of the elderly in the US. Over 35 million Americans provided informal care to someone age 50 and older in 20151. Most studies focus on the direct health care costs of aging, ignoring the costs associated with informal care. When the costs of informal care are computed, studies tend to use relatively straightforward methods, primarily relying on replacement cost or forgone wage approaches. Replacement cost methods multiply the hours of informal care provided by the wage that a formal home health care provider would earn. The foregone wage approach uses the caregiver’s own potential market wage to value each hour of informal care provided.

Both of these methods ignore important aspects of the true cost of informal care. Individuals providing informal care are impacted beyond current foregone earnings. For example, all caregivers provide care at the cost of some other activity, either leisure or employment. Foregone wage approaches do not incorporate the value of foregone leisure. For individuals who leave work or decrease their work hours to provide care, future labor market opportunities can be affected, making it difficult to return to work at their previous wage or hours. Finally, people who provide informal care might do so because it gives them some intrinsic benefit, such as fulfilling a familial duty2. Neither the replacement cost nor the foregone wage approaches consider these long-term costs or non-tangible benefits.

Further, these methods do not capture heterogeneity in the costs of care due to the health status of the care recipient. There are three reasons this is important: (1) Providing informal care for someone with a memory-related disease may be a different experience than caring for someone with only ADL limitations; (2) Memory-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), use a disproportionate share of informal care. In 2014, one-third of caregivers providing care to someone age 65 and older reported that their loved one has a memory problem; and (3) Memory-related diseases currently impact over 5 million Americans and their prevalence is predicted to double within the next 30 years3. Studies estimate that informal care increases the cost of ADRD by an additional 50–100 percent over and above the health care costs4–9, but again, use static methods that ignore the dynamic nature of the cost to the caregiver’s well-being1.

This paper estimates a more comprehensive cost of informal care that includes the value of time, the implications for future employability and wages, and any intrinsic benefits accrued for daughters who provide care to their mothers. Economists refer to this collection of costs as “welfare cost.” Using a dynamic discrete choice model, we allow those costs to differ by whether the mother has a memory-related disease, with and without accompanying ADL limitations, allowing us to more directly compare our cost estimates to those that focus on ADRD care using more traditional, static methods.

METHODS

Data

Survey data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a longitudinal survey with information on labor supply, family structure, intergenerational transfers, health, income, and assets were used. Baseline interviews occurred in 1992, with biennial follow-up. We use data from 1998–2012, when questions about parental memory-related diseases were asked. All HRS data used were de-identified, and all respondents provided informed consent under protocols approved by the University of Michigan’s institutional review board.

We focus on daughters at risk for providing informal care to their mothers by limiting the sample to female respondents between the ages of 40 and 70 who have a living mother at the start of the sample period. We do so for two reasons. First, the impact of caregiving on well-being may differ based on the characteristics of both the caregiver and the care recipient, such as gender concordance10. Second, the most prevalent intergenerational caregiving arrangement, both nationwide3 and in survey data11, is daughters providing care to their mothers. The final sample consists of 3,427 women and 14,645 person-wave observations.

Measures

In the HRS, respondents are asked whether they or their spouses spent 100 or more hours in the past two years helping their parents with “basic personal needs like dressing, eating, and bathing.” Follow-up questions are asked about who was helped and how many hours of care were separately provided by the respondent and her spouse. Respondents were also asked whether they helped with “household chores, errands, transportation, etc.”, with similar follow-up questions. A woman is defined as a caregiver if she provided either type of care, and the hours she spent providing both types of care are summed to determine the amount of her care provision. We distinguish between light (less than 1,000 hours of care over a two-year period) and intensive (1,000 or more hours of care) caregiving. In the implementation of the model, we assign the median number of hours of care to each group, 200 hours and 1,560 hours of care per period for light and intensive care, respectively.

In the model, women can not work, work part-time, or work full-time. Those who work part-time are assumed to work 2,000 hours per two-year period, and those who work full-time work 4,000 hours per two-year period. Additional covariates include the woman’s education, non-labor income, and information about family structure. In particular, in each wave, the woman reports her marital status, the number of living siblings, and the gender of those siblings.

The HRS asks each respondent about her parent’s health. In particular, the respondent is asked whether her mother needs help with activities of daily living (ADLs), whether she can be left alone for an hour or more, and after 1996, whether the mother has ever been told by a doctor that she has a memory-related disease. We use these measures to define six health states: (1) healthy; (2) has ADL limitations only; (3) has a memory-related disease only; (4) has both ADL limitations and a diagnosed memory-related disease; (5) cannot be left alone for an hour or more; and (6) death. While there are a variety of ailments that could lead to an individual not being able to be left alone, two-thirds of this group are also reported to have a doctor-diagnosed memory-related disease.

Analysis

Discrete choice models describe and predict the choices people make when deciding between two or more alternatives, for example, working or not, or providing informal care or not. Dynamic discrete choice models recognize that these decisions are not static, one-time decisions, but rather decisions that have implications for future periods, particularly future well-being. In this paper we use a dynamic discrete choice model that follows directly from Skira (2015). Details of the model can be found in the online supplemental material. The main point of departure from the earlier model is the more granular classification of maternal health11.

This methodology allows us to perform the following mental exercise. In each two-year period, the adult daughter makes decisions about how to spend her time between leisure, work (no work, part-time, full-time), and informal care (no care, light care, intensive care) to maximize her well-being not just today, but over her lifetime. For example, a daughter who decides to work full- or part-time today knows her expected wage offer will be higher next period due to the returns to experience and human capital formation. If she decides to work part-time today rather than full-time, her hourly wage may be lower if part-time jobs earn less than full-time ones, and her ability to find a full-time job in the future may be lower if there are difficulties moving between full- and part-time employment. Finally, if she opts to not work at all, working in the future may be difficult as she will likely face limited job offers and lower wages due to the loss of human capital.

Informal care can impact individual well-being in the following ways:

Direct utility impact: Caregiving can directly impact well-being – one could like it or dislike it. Caregiving effects on well-being can vary by duration (first time providing care vs. continuing providing care), the health of the parent (ADL limitations, memory-related disease, combination of the two, cannot be left alone), and whether or not there is a sister who could potentially share the responsibility.

Indirect effect through a change in leisure time: Some individuals may value leisure more than others, and this valuation may change with age (for example, after retirement, individuals may value each additional hour of leisure more or less).

Indirect effect through a change in labor market opportunities and earnings: Providing informal care may impact how much one works today, impacting their consumption today, as well as their wages and employability in the future.

The value of these effects is derived by observing a daughter’s decisions about caregiving, work, and leisure as a mother progresses through these health states.

The daughter’s well-being is measured by observing her choices, or what economists refer to as ‘revealed preference’. Individuals choose the options that give them the highest expected lifetime well-being. Variation in choices across individuals and across time identifies the preference parameters (along with functional form assumptions, distributional assumptions, and normalizations), and well-being is quantified using these parameters and observed choices about caregiving, work, and leisure as the mother’s health status and the daughter’s work opportunities change.

We use the estimated model to calculate the well-being of each daughter when she has the choice to provide informal care (e.g., the baseline model). In a separate simulation exercise, for all women ages 55 and 56 with an ill mother, we remove the choice of not providing care and “force” them to provide informal care in that period. When we “force” women to provide care, they still optimize their well-being through their remaining choices regarding time spent working and time spent on leisure. We then compare the daughter’s well-being between the two scenarios. For women who provided care in the baseline scenario, their change in well-being is zero.

We calculate the costs of informal care among those women whose caregiving behavior changed from not providing care in the baseline scenario to providing it in the simulation. We report the median costs to well-being, which is the lump-sum amount of money the median woman would have to receive to be just as well off in the two scenarios. We calculate foregone labor earnings due to caregiving by limiting the sample to those women who change their caregiving behavior and change their work decisions when we remove the option to not provide care.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for our (unweighted) sample of women based on their current caregiving status (those with a mother no longer alive, non-caregivers (with a mother alive), light caregivers, and intensive caregivers). Not surprisingly, caregiving experiences a positive age gradient. There is also a positive relationship between not working and caregiving intensity, which suggests difficulty in combining work with caregiving responsibilities. However, there is little relationship between education and these categories. Caregiving frequency and intensity increase as mothers’ health declines. The percent married varies across these categories, likely reflecting both an increase in widowhood as women age as well as differential time/availability to provide care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women by Caregiving Status

| Mother No Longer Alive | Non-Caregiver | Light Caregiver | Intensive Caregiver | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment | ||||

| % Not working | 55.3 | 37.1 | 38.1 | 52.6 |

| % Working part-time | 17.4 | 18.2 | 21.1 | 19.4 |

| % Working full-time | 27.3 | 44.7 | 40.8 | 28.0 |

| Mother’s Health | ||||

| % Healthy | 76.9 | 64.9 | 37.2 | |

| % ADL problems (only) | 6.9 | 12.7 | 18.4 | |

| % Memory-related disease (only) | 2.6 | 5.6 | 5.1 | |

| % ADL and memory-related disease (can be left alone) | 2.5 | 5.6 | 11.6 | |

| % Cannot be left alone | 11.1 | 11.2 | 27.8 | |

| Demographics and Family Structure | ||||

| Mean age | 62.1 | 56.9 | 58.4 | 59.5 |

| % Married | 77.5 | 82.5 | 81.1 | 75.0 |

| % Has sister | 72.0 | 75.9 | 72.8 | 66.5 |

| % Less than high school | 16.4 | 14.7 | 9.7 | 9.1 |

| % High school education | 36.3 | 34.8 | 37.6 | 36.3 |

| % Some college | 47.2 | 50.5 | 52.7 | 54.6 |

| Mean years of work experience | 28.3 | 26.0 | 28.2 | 27.7 |

| N | 5,610 | 5,640 | 2,714 | 681 |

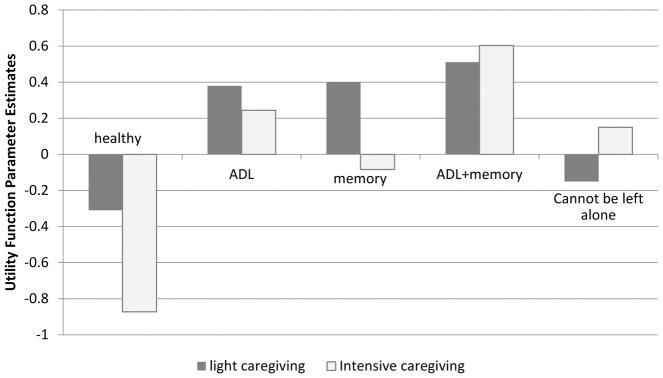

In Figure 1, we present estimates of the direct utility effects of care provision by the health state of the mother and the intensity of care provision. (Main model parameter estimates are available in the Appendix.) Providing informal care to a mother who has neither ADL limitations nor memory-related disease decreases the well-being of the daughter, no matter how many hours of care are provided. Light caregiving shows a concave relationship with well-being across the health states, positively affecting the well-being of the daughter across all health states except the healthiest and the sickest.

Figure 1. Direct Utility Impact of Caregiving on Well-being, by Health of Mother.

ADL = Activities of Daily Living

Light Caregiving = Women who provide less than 1,000 hours of care over a two-year period.

Intensive Caregiving = Women who provide 1,000 or more hours of care over a two-year period.

Intensive caregiving does not exhibit the same concave pattern. The most noteworthy difference is between ADL limitations (only) and memory-related disease (only). Intensive caregiving for mothers with memory-related disease decreases well-being, whereas caregiving for mothers with ADL limitations increases well-being. Only when memory-impairment is combined with ADL limitations does intensive caregiving yield positive direct effects on well-being.

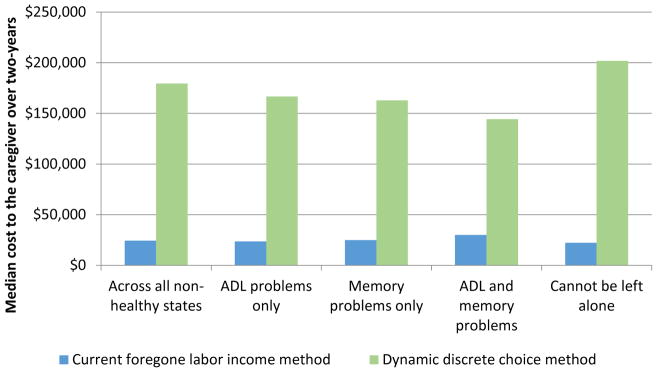

Figure 2 presents two estimates of the cost of care provision by the health state of the mother: median current foregone earnings and the median cost to well-being. The first methodology leads to an estimate of $24,500 over a two-year period over all health states, with relatively little variation over the health states. These estimates align with those found in the literature, which range from $21,220–$26,043 (in 2008 dollars)11–14.

Figure 2.

Cost Estimates of Informal Care (Over a Two-Year Period)

ADL = Activities of Daily Living

The estimate of the median cost to well-being, over all health states, is approximately $180,000 over a two-year period, about seven times the cost estimate using the current foregone wage approach. In addition, there is more variation in the cost to well-being across health states. The costs to a daughter’s well-being of caring for someone with memory-related disease varies considerably, depending if ADL limitations are also present. For example, caring for someone with memory-related disease but no ADL limitations costs approximately $163,000; very similar to the costs of providing care for a mother who only has ADL limitations ($167,000). However, when memory issues are paired with ADL limitations, the costs of caregiving actually decrease to $144,000. The costs are driven down due to the direct positive utility impact of caregiving for mothers with both memory–related disease and ADL limitations, illustrated in Figure 1. When the mother cannot be left alone for more than one hour, the costs again rise to over $200,000 over a two-year period.

DISCUSSION

Focusing on the most prevalent caregiving dyad, we estimate the effects of caregiving on the well-being of the informal care provider. We compare foregone wages due to caregiving to a more comprehensive measure of cost that accounts for the dynamic nature of caregiving, the long-term impact on earnings and work, the impact on leisure, and the direct impact of caregiving on well-being. Our preferred method suggests the median cost to well-being is approximately $180,000, seven times the foregone wage estimate. To put these costs into perspective, the average cost of a semi-private bed in a nursing home was $85,775 in 2017, implying a two-year cost of nursing home care of $171,55015. Our results suggest the costs of informal care to a daughter’s well-being are in the same ballpark as full-time institutional care. The cost comparability suggests that further work is needed in assessing the benefits of these two very different types of care. The BrightFocus Foundation’s recent recommendations include making home the nexis of dementia care, but recognizes the need to put in place numerous community-based interventions to maximize quality of life16.

This work highlights that there is important heterogeneity in the costs of informal care to the daughter’s well-being based on the health of the mother receiving care. There are a variety of plausible mechanisms that could explain the non-linear relationship between the direct utility effects of caregiving and the mother’s health. The direct utility effects reflect both utility gains from care provision, which may be derived from reciprocity, responsibility norms, or altruism, as well as the utility losses from care provision, which may stem from caregiving being stressful and burdensome. Providing care may lead to larger net benefits to the caregiver as the care recipient gets sicker, but when health impairments become severe, caregiving may become particularly burdensome. Intensive caregiving to someone with memory issues provides lower direct utility to the caregiver than providing care to someone with ADL limitations. This difference could be driven by more clear understanding, by the caregiver and other support systems, of what is needed to provide care for someone with an ADL limitation as opposed to a memory problem. While caring for someone with memory issues seems to have the same implications for well-being as caring for someone with only ADL limitations, combining the two types of health problems makes a big difference in terms of cost.

In order to gauge the economic importance of caregiving, we do a back-of-the-envelope calculation. There were an estimated 14.7 million family and unpaid caregivers in 2011, approximately half of which were children providing care to parents, and approximately half of the care recipients had dementia17. Using the most conservative estimates of the median costs to the daughter’s well-being related to memory-related disease and assuming they are a lower bound for other caregiving dyads, the cost of informal care was at least $277 billion in 2011, twenty percent higher than the current estimate of $230.1 billion3.

Our study has limitations. Structural models in general, of which dynamic discrete choice models are one, require a detailed specification of the decision-making problem. We must specify the constraints, preferences and determinants of well-being, and choices people face explicitly. While we tested many assumptions and conducted numerous sensitivity analyses to insure the robustness of our estimates, they may be biased if we have misspecified the model. For example, we miss small adjustments in hours worked because of the discrete nature of the choices. We limit our analysis to mother-daughter dyads, the most common intergenerational caregiving relationship observed. Our estimates may not be generalizable to other intergenerational caregiving pairs. Finally, we are limited in our definition of the health of the care recipient due to the survey data; these are self-reported health measures by the daughter and not clinical assessments. Further, we cannot tease apart different conditions distinctly, or identify the presence or severity of behavioral issues which likely complicate the caregiving relationship.

CONCLUSION

As the long-term care service and supports policy continues to discuss “rebalancing,”18 or reducing the bias towards institutionalization in insurance coverage, the costs to the caregiver’s well-being must be kept in mind. Moving someone from full-time institutional care to home, even with the support of formal home health care or community-based care as recommended by the BrightFocus Foundation16, inevitably requires additional support provided by the family19. When only considering forgone earnings due to caregiving, these policy changes may seem to be cost-reducing on a societal level; however, accounting for the cost to the well-being of the caregiver may alter the calculation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table A1: Structural Parameter Estimates

Supplementary Table A2: Estimated Offer Probabilities

Supplementary Text S1. Appendix

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: We would like to acknowledge funding from the National Institute of Health (R01 AG049815) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (SIP 14-005).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Checklist:

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | Norma B. Coe | Meghan M. Skira | Eric B. Larson | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | |||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | |||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | |||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | |||

| Consultant | X | X | X | |||

| Stocks | X | X | X | |||

| Royalties | X | X | X | |||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | |||

| Board Member | X | X | X | |||

| Patents | X | X | X | |||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | |||

Author’s Contributions: Dr. Coe and Dr. Skira made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study, drafting, revising, and final approval of the manuscript. Dr. Skira also made contributions for the acquisition of data, the analysis, and interpretation of data. Dr. Larson made substantial contributions to the drafting, revising, and final approval of the manuscript.

Sponsor’s Role: The funders, the National Institute on Aging and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, had no input on the work presented.

References

- 1.National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP Public Policy Institute. Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuifbergen MC, Van Delden JJM. Filial obligations to elderly parents: a duty to care? Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy. 2011;14(1):63–71. doi: 10.1007/s11019-010-9290-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s A. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(4):459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Torgan R, et al. Clinical characteristics and longitudinal changes of informal cost of Alzheimer’s disease in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1596–1602. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu CW, Torgan R, Scarmeas N, et al. Home health and informal care utilization and costs over time in Alzheimer’s disease. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2008;27(1):1–20. doi: 10.1300/J027v27n01_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Z, Levey A. Gender Differences: A Lifetime Analysis of the Economic Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(5):436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Langa KM. Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(5):489–490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1305541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The Burden of Health Care Costs for Patients With Dementia in the Last 5 Years of Life. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;163(10):729–U175. doi: 10.7326/M15-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rattinger GB, Schwartz S, Mullins CD, et al. Dementia severity and the longitudinal costs of informal care in the Cache County population. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(8):946–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noël-Miller C. Spousal loss, children, and the risk of nursing home admission. The journals of gerontology, Series B. 2010;65B(3):370–380. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skira MM. Dynamic wage and employment effects of elder parent care. International Economic Review. 2015;56(1):63–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson RA, Lo Sasso A. Located at: Working Paper. Washington, DC: The Trade-off between Hours of Paid Employment and Time Assistance to Elderly Parents at Midlife 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinberg LF, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R. Insignts on the Issues. Vol. 51. Washington DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2011. Valuing the Invaluable: 2011 Update: the Grouwing Contributions and Costs of Family Caregiving. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(14):1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organization AECR. How to Pay for Nursing Hoem Care/Convalescent Care. 2017 https://www.payingforseniorcare.com/longtermcare/paying-for-nursing-homes.html.

- 16.Samus QM, Black BS, Bovenkamp D, et al. Home is where the future is: The BrightFocus Foundation consensus panel on dementia care. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2016;14(1):104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff JL, Spillman BC, Freedman VA, Kasper JD. A National Profile of Family and Unpaid Caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(3):372–379. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaye HS. Gradual rebalancing of Medicaid long-term services and supports saves money and serves more people, statistical model shows. Health Aff. 2012;31:1195–1203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konetzka R. The hidden costs of rebalancing long-term care. Health services research. 2014;49(3):771–777. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table A1: Structural Parameter Estimates

Supplementary Table A2: Estimated Offer Probabilities

Supplementary Text S1. Appendix