Abstract

Missed clinic visits can lead to poorer treatment outcomes in HIV-infected patients. Suboptimal antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence has been linked to subsequent missed visits. Knowing the determinants of missed visits in Asian patients will allow for appropriate counselling and intervention strategies to ensure continuous engagement in care.

A missed visit was defined as having no assessments within six months. Repeated measures logistic regression was used to analyse factors associated with missed visits.

A total of 7100 patients were included from 12 countries in Asia with 2676 (37.7%) having at least one missed visit. Patients with early suboptimal self-reported adherence <95% were more likely to have a missed visit compared to those with adherence ≥95% (OR=2.55, 95% CI(1.81–3.61)). Other factors associated with having a missed visit were homosexual (OR=1.45, 95%CI(1.27–1.66)) and other modes of HIV exposure (OR=1.48, 95%CI(1.27–1.74)) compared to heterosexual exposure; using PI-based (OR=1.33, 95%CI(1.15–1.53) and other ART combinations (OR=1.79, 95%CI(1.39–2.32)) compared to NRTI+NNRTI combinations; and being hepatitis C co-infected (OR=1.27, 95%CI(1.06–1.52)). Patients aged >30 years (31–40 years OR=0.81, 95%CI(0.73–0.89); 41–50 years OR=0.73, 95%CI(0.64–0.83); and >50 years OR=0.77, 95%CI(0.64–0.93)); female sex (OR=0.81, 95%CI(0.72–0.90)); and being from upper middle (OR=0.78, 95%CI(0.70–0.80)) or high-income countries (OR=0.42, 95%CI(0.35–0.51)), were less likely to have missed visits.

Almost 40% of our patients had a missed clinic visit. Early ART adherence was an indicator of subsequent clinic visits. Intensive counselling and adherence support should be provided at ART initiation in order to optimise long term clinic attendance and maximise treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Asia, adherence, missed visit, HIV

Introduction

Continuous engagement in care after HIV diagnosis often maximises responses to ART and increases viral load (VL) suppression(Mugavero et al., 2012). Missed clinical visits or “no show” have shown to be associated with higher mortality rates in both resource-rich and resource-limited settings(Horberg et al., 2013; Y. Zhang et al., 2012). The risk for mortality also increases with higher frequency of missed visits in patients retained in care(Mugavero et al., 2014). Predictors of missed visits often include female sex, younger age, injecting drug users (IDU), and lower CD4 cell count(Horberg, et al., 2013; Y. Zhang, et al., 2012).

Little is known about missed visits in HIV-infected population in Asia. In loss to follow-up (LTFU) studies, it has been reported that ART adherence levels can be an important predictor of LTFU, in addition to other patient and clinical characteristics(Tran et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2012). Although patients having missed clinical visits would most likely return for further clinical care, early ART adherence levels may be a good indicator of future clinic attendance.

The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD) is a prospective cohort consisting of 20 sites in 12 countries in Asia(TAHOD, 2016; Zhou et al., 2005). Determining the extent of missed visits in this cohort, where ART combinations are often limited, will not only allow for appropriate intervention strategies to be implemented, but will enable health care providers to establish long term treatment plan to ensure that optimal treatment responses can be achieved.

Methods

Study population

Patients enrolled in TAHOD in the September 2015 data capture who had initiated ART were included in the analyses. Countries within TAHOD include Cambodia, China and Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam.

Definitions

ART adherence was obtained from the WHO endorsed(Obermeyer et al., 2009) self-reported 30-day adherence visual analogue scale(Jiamsakul et al., 2014) (VAS). ART adherence used in this study was the assessment recorded in the first six months of ART initiation categorised(Obermeyer, et al., 2009) as (i) <95%, (ii) ≥95%, and (iii) Not done. We chose adherence levels in the first six months as our previous study suggests that suboptimal adherence occurred in highest proportions in the first 6 months of ART, and decreased thereafter(Jiamsakul, et al., 2014).

Analysis follow-up time began from the latter of ART initiation date or cohort entry date. Follow-up time was divided into six-monthly intervals, up to a maximum of five years. As the TAHOD database does not record scheduled or cumulative clinic visit attendances, a missed visit in this study was defined as having no clinical or laboratory attendance/assessments in each of the six-monthly intervals.

Patients were considered at risk of having a missed after six months from analysis start time as all patients in the study were expected to have a clinic visit in the first six months due to our endpoint definition and inclusion criteria. LTFU patients were categorised as having missed visits for 12 months after their last visit date, after which they were censored from the analysis datasets.

Statistical analyses

Factors associated with missed visits were analysed using repeated measures logistic regression (generalised estimating equations, GEE), using exchangeable correlation structure. Regression models were fitted using backward stepwise procedures. A sensitivity analysis was performed by restricting the study population to patients who had an adherence assessment available in the first six months.

Ethics approvals were obtained from respective local ethics committees of all TAHOD-participating sites, the data management and biostatistical center (UNSW Sydney Ethics Committee), and the coordinating centre (TREAT Asia/amfAR). All data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata software version 14.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Of the 7100 patients included, 2676 (37.7%) had at least one missed visit. Of those who have had a missed visit, 845 (31.6%) patients subsequently became LTFU. Table 1 shows characteristics of the patient group consisting of mostly male patients (70.0%), with an overall median age of 34 years (IQR: 29–41). Adherence in the first six months after ART initiation was reported in 35.8% of patients. The median CD4 cell count prior to ART initiation was 128 cells/¼L (IQR: 41–255), and median VL was 97100 copies/mL (IQR: 28400–280000).

Table 1:

Patient characteristics

| Total patients (%) | Patients with at least one missed visit (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 7100 (100.0) | N = 2676 (37.7) | |

| ART adherence in the first six months | ||

| ≥ 95% | 2383 (33.6) | 478 (17.9) |

| <95% | 158 (2.2) | 50 (1.9) |

| Not done | 4559 (64.2) | 2148 (80.3) |

| Age at ART initiation (years) | Median = 34 (IQR: 29–41) | Median = 33 (IQR: 28–40) |

| ≤30 | 2238 (31.5) | 963 (36.0) |

| 31–40 | 3022 (42.6) | 1116 (41.7) |

| 41–50 | 1308 (18.4) | 428 (16.0) |

| >50 | 532 (7.5) | 169 (6.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 4967 (70.0) | 1978 (73.9) |

| Female | 2133 (30.0) | 698 (26.1) |

| HIV mode of exposure | ||

| Heterosexual contact | 4506 (63.5) | 1598 (59.7) |

| Homosexual contact | 1545 (21.8) | 638 (23.8) |

| Injecting drug use | 531 (7.5) | 202 (7.5) |

| Other/Unknown | 518 (7.3) | 238 (8.9) |

| Pre-ART viral Load (copies/mL) | Median = 97100 (IQR: 28400–280000) | Median = 100000 (IQR: 27968–310000) |

| ≤50000 | 1195 (16.8) | 431 (16.1) |

| 50001–250000 | 1303 (18.4) | 452 (16.9) |

| >250000 | 912 (12.8) | 353 (13.2) |

| Not done | 3690 (52.0) | 1440 (53.8) |

| Pre-ART CD4 (cells/¼L) | Median = 128 (IQR: 41–225) | Median = 145.5 (IQR: 51–233) |

| ≤50 | 1729 (24.4) | 511 (19.1) |

| 51–100 | 840 (11.8) | 263 (9.8) |

| 101–200 | 1510 (21.3) | 573 (21.4) |

| >200 | 1863 (26.2) | 701 (26.2) |

| Not done | 1158 (16.3) | 628 (23.5) |

| Initial ART Regimen | ||

| NNRTI-based | 6032 (85.0) | 2214 (82.7) |

| PI-based | 976 (13.7) | 420 (15.7) |

| Other combination | 92 (1.3) | 42 (1.6) |

| Hepatitis B co-infection | ||

| Negative | 4906 (69.1) | 1635 (61.1) |

| Positive | 562 (7.9) | 168 (6.3) |

| Not tested | 1632 (23.0) | 873 (32.6) |

| Hepatitis C co-infection | ||

| Negative | 4309 (60.7) | 1230 (46.0) |

| Positive | 759 (10.7) | 281 (10.5) |

| Not tested | 2032 (28.6) | 1165 (43.5) |

| pre-ART AIDS Diagnosis | ||

| No | 4457 (62.8) | 1673 (62.5) |

| Yes | 2643 (37.2) | 1003 (37.5) |

| Country income | ||

| Low and lower middle | 2975 (41.9) | 1264 (47.2) |

| Upper middle | 2658 (37.9) | 980 (36.6) |

| High | 1467 (20.7) | 432 (16.1) |

Factors associated with missed visit events are presented in Table 2. In multivariate analyses, adjusting for follow-up time, patients reporting suboptimal ART adherence <95% in the first six months were more likely to have subsequent missed visits compared to those with adherence ≥95% (OR=2.55, 95% CI (1.81–3.61), p<0.001). Other clinical characteristics associated with having missed visits were homosexual HIV mode of exposure (OR=1.45, 95% CI (1.27–1.66), p<0.001) and other/unknown (OR=1.48, 95% CI (1.27–1.74), p<0.001), compared to heterosexual mode of exposure; initiating on an nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) plus protease inhibitor (PI) (OR=1.33, 95% CI (1.15–1.53), p<0.001), and other combinations (OR=1.79, 95% CI (1.39–2.32), p<0.001) compared to a non-NRTI (NNRTI) -based regimen; and being hepatitis C co-infected (OR=1.27, 95%CI (1.06–1.52), p=0.011). Factors associated with decreased odds of having missed visits were age >30 years (31–40 years: OR=0.81, 95% CI (0.73–0.89), p<0.001, 41–50 years: OR=0.73, 95% CI (0.64–0.83), p<0.001, and >50 years: OR=0.77, 95% CI (0.64–0.93), p=0.006); female sex (OR=0.81, 95% CI (0.72–0.90), p<0.001); and being from upper middle-income (OR=0.78, 95% CI (0.70–0.86), p<0.001) and high-income countries (OR=0.42, 95% CI (0.35–0.51), p<0.001) compared to low and lower middle-income countries.

Table 2:

Factors associated with missed visits.

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #Total Missed Visits | OR | 95% CI | *p-value | OR | 95% CI | *p-value | |

| ART adherence in the first six months | |||||||

| ≥ 95% | 912 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <95% | 99 | 2.15 | (1.53, 3.01) | <0.001 | 2.55 | (1.81, 3.61) | <0.001 |

| Not done | 5189 | ||||||

| Age at ART initiation | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| ≤30 | 2237 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 31–40 | 2657 | 0.81 | (0.73, 0.89) | <0.001 | 0.81 | (0.73, 0.89) | <0.001 |

| 41–50 | 933 | 0.66 | (0.57, 0.75) | <0.001 | 0.73 | (0.64, 0.83) | <0.001 |

| >50 | 373 | 0.65 | (0.54, 0.79) | <0.001 | 0.77 | (0.64, 0.93) | 0.006 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 4581 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1619 | 0.81 | (0.73, 0.89) | <0.001 | 0.81 | (0.72, 0.90) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis B co-infection | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Heterosexual contact | 3792 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Homosexual contact | 1403 | 1.08 | (0.97, 1.20) | 0.146 | 1.45 | (1.27, 1.66) | <0.001 |

| Injecting drug use | 393 | 1.08 | (0.91, 1.28) | 0.390 | 0.87 | (0.70, 1.08) | 0.197 |

| Other/Unknown | 612 | 1.50 | (1.29, 1.75) | <0.001 | 1.48 | (1.27, 1.74) | <0.001 |

| Pre-ART viral Load (copies/mL) | 0.633 | ||||||

| ≤50000 | 983 | 1 | |||||

| 50001–250000 | 1058 | 0.95 | (0.82, 1.11) | 0.548 | |||

| >250000 | 791 | 1.03 | (0.88, 1.21) | 0.719 | |||

| Not done | 3368 | ||||||

| Pre-ART CD4 (cells/¼L) | 0.001 | ||||||

| ≤50 | 1186 | 1 | |||||

| 51–100 | 614 | 1.10 | (0.93, 1.31) | 0.277 | |||

| 101–200 | 1368 | 1.34 | (1.17, 1.54) | <0.001 | |||

| >200 | 1601 | 1.29 | (1.13, 1.47) | <0.001 | |||

| Not done | 1431 | ||||||

| Initial ART Regimen | 0.008 | <0.001 | |||||

| NNRTI-based | 5097 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| PI-based | 985 | 1.04 | (0.92, 1.17) | 0.509 | 1.33 | (1.15, 1.53) | <0.001 |

| Other combination | 118 | 1.63 | (1.19, 2.23) | 0.002 | 1.79 | (1.39, 2.32) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis B co-infection | |||||||

| Negative | 3513 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 383 | 0.92 | (0.76, 1.11) | 0.379 | |||

| Not tested | 2304 | ||||||

| Hepatitis C co-infection | |||||||

| Negative | 2469 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 544 | 1.49 | (1.28, 1.73) | <0.001 | 1.27 | (1.06, 1.52) | 0.011 |

| Not tested | 3187 | ||||||

| pre-ART AIDS Diagnosis | |||||||

| No | 3869 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 2331 | 1.03 | (0.94, 1.13) | 0.556 | |||

| Country income | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Low and lower middle | 3097 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Upper middle | 2212 | 0.77 | (0.70, 0.85) | <0.001 | 0.78 | (0.70, 0.86) | <0.001 |

| High | 891 | 0.50 | (0.44, 0.56) | <0.001 | 0.42 | (0.35, 0.51) | <0.001 |

Total missed visits include all repeated missed visits. A patient can have more than one missed visit during follow-up.

Global p-values are test for heterogeneity excluding missing values.

Multivariate model is adjusted for follow-up time.

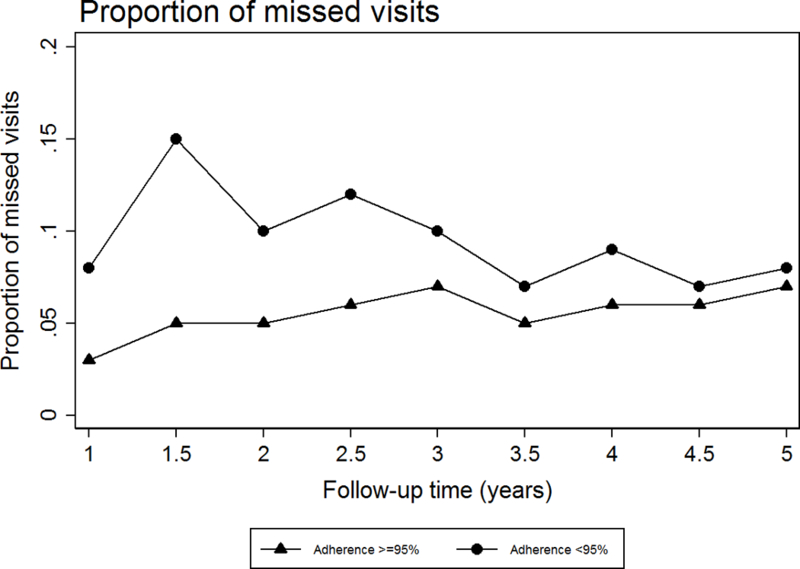

The differences in ART adherence levels and their association with missed visits are illustrated in Figure 1. Proportion of patients with missed visits over five years were consistently higher for those who reported adherence <95% in the first six months. Missed visits in those with adherence ≥95% slightly increased over time from 3% to 7%, while the proportions fluctuated between 8% and 15% in the suboptimal adherence group.

Figure 1: Proportion of missed visits over time by ART adherence levels in the first six months.

*Follow-up time is time from ART initiation or cohort entry.

When we restricted our study population to patients who had an adherence measurement available in the first six months after ART initiation, we found that adherence has maintained its association with missed visits. We found that among the 2541 patients with adherence available, patients who had adherence <95% were at least two times more likely to have a subsequent missed visit during follow-up (OR=2.40, 95%CI (1.65–3.48), p<0.001).

Discussion

Missed visits occurred in almost 40% of our patient group. Patients with suboptimal adherence were more likely to have subsequent missed visits compared to patients with adherence ≥95%. Other factors associated with missed visits included homosexual and other/unknown mode of HIV exposure, PI-based and other ART combination first-line regimen, and being hepatitis-C positive. Factors showing decreasing likelihood of missed visits were older age, female sex, and being from upper middle- and high-income countries.

Our study suggests that ART adherence was an important factor in determining subsequent clinic attendance, which was consistent with findings from other resource-rich settings(Woodward et al., 2015). The significant association between adherence and missed visits in both the main and sensitivity analyses indicate that adherence levels should be carefully monitored, particularly immediately after ART initiation, to ensure that life-long HIV treatment schedules can be maintained and adhered to. Socioeconomic and psychosocial risk factors(Ayer et al., 2016; Wawrzyniak et al., 2015), have been reported to affect clinic attendance. TAHOD, however, does not routinely collect socioeconomic risk factors, but the decreasing odds of missed visits with higher country income levels signal the underlying socioeconomic barriers to continuous engagement in care in our patient group.

There is limited literature investigating the association of other clinical characteristics with missed visits, especially in resource-limited settings. However, our results are comparable to reported studies which showed that younger patients, males, and those with hepatitis C co-infection were more likely to have discontinuous engagement in care(Asiimwe, Kanyesigye, Bwana, Okello, & Muyindike, 2016; Mburu et al., 2016; Megerso et al., 2016; Rachlis et al., 2016; F. Zhang et al., 2014). We also found that PI-based first-line regimen was associated with increased odds of missed visits, which could be due to the toxicities associated with PI drugs(Zhou, et al., 2012). Heterosexual mode of exposure has been shown in different studies to be associated with an increased risk of missed visits or LTFU(McManus et al., 2015; Rachlis, et al., 2016). This is contrast to our findings where the association was seen in homosexual HIV exposure group. This may reflect the stigma and discrimination faced by this population potentially leading to disengagement in care.

A limitation of this study includes the nature of the data collection in TAHOD where scheduled or cumulative visit dates were not captured. We could not ascertain scheduled clinic appointments in each of the six-monthly intervals and therefore the reported missed visits may not represent the true proportion. Another limitation is the high percentage (64.2%) of patients without an adherence assessment in the first six months of ART initiation. This is because adherence information was not routinely collected in TAHOD until 2011. The sensitivity analysis, however, reported a significant association between suboptimal adherence and missed visits, thus indicating the importance of ART adherence in determining future clinic attendance. Lastly, as we did not control for site in the regression analysis due to potential collinearity with country-income level, we were not able to determine the association between site-level effects with missed visits.

Conclusions

This study found that patients with early suboptimal ART adherence were at increased risk of not attending future clinic appointments. Patients with poor adherence should be targeted in order to improve retention in care. Appropriate support should be provided at ART initiation to maximise treatment uptake in the first six months.

Acknowledgements

The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database is an initiative of TREAT Asia, a program of amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, with support from the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, as part of the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA; U01AI069907). The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Sydney. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the governments or institutions mentioned above.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

TAHOD study members

PS Ly* and V Khol, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology & STDs, Phnom Penh, Cambodia;

FJ Zhang* ‡, HX Zhao and N Han, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China;

MP Lee*, PCK Li, W Lam and YT Chan, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, China;

N Kumarasamy*, S Saghayam and C Ezhilarasi, Chennai Antiviral Research and Treatment Clinical Research Site (CART CRS), YRGCARE Medical Centre, VHS, Chennai, India;

S Pujari*, K Joshi , S Gaikwad and A Chitalikar, Institute of Infectious Diseases, Pune, India;

TP Merati*, DN Wirawan and F Yuliana, Faculty of Medicine Udayana University & Sanglah Hospital, Bali, Indonesia;

E Yunihastuti*, D Imran and A Widhani, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia - Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia;

J Tanuma*, S Oka and T Nishijima, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan;

JY Choi*, Na S and JM Kim, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea;

BLH Sim*, YM Gani, and R David, Hospital Sungai Buloh, Sungai Buloh, Malaysia;

A Kamarulzaman*, SF Syed Omar, S Ponnampalavanar and I Azwa, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia;

R Ditangco*, E Uy and R Bantique, Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Manila, Philippines;

WW Wong* †, WW Ku and PC Wu, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan;

OT Ng*, PL Lim, LS Lee and PS Ohnmar, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore;

A Avihingsanon*, S Gatechompol, P Phanuphak and C Phadungphon, HIV-NAT/Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand;

S Kiertiburanakul*, S Sungkanuparph, L Chumla and N Sanmeema, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand;

R Chaiwarith*, T Sirisanthana, W Kotarathititum and J Praparattanapan, Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai, Thailand;

P Kantipong* and P Kambua, Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiang Rai, Thailand;

KV Nguyen*, HV Bui, DTH Nguyen and DT Nguyen, National Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Hanoi, Vietnam;

DD Cuong*, NV An and NT Luan, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam;

AH Sohn*, JL Ross* and B Petersen, TREAT Asia, amfAR - The Foundation for AIDS Research, Bangkok, Thailand;

DA Cooper, MG Law*, A Jiamsakul* and DC Boettiger, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, NSW, Australia.

* TAHOD Steering Committee member; † Steering Committee Chair; ‡ co-Chair

References

- Asiimwe SB, Kanyesigye M, Bwana B, Okello S, & Muyindike W. (2016). Predictors of dropout from care among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy at a public sector HIV treatment clinic in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Infect Dis, 16, p 43. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1392-7 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26832737https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4736127/pdf/12879_2016_Article_1392.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayer R, Kikuchi K, Ghimire M, Shibanuma A, Pant MR, Poudel KC, & Jimba M. (2016). Clinic Attendance for Antiretroviral Pills Pick-Up among HIV-Positive People in Nepal: Roles of Perceived Family Support and Associated Factors. PLoS One, 11(7), p e0159382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159382 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27438024https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4954679/pdf/pone.0159382.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Silverberg MJ, Klein DB, Quesenberry CP, & Mugavero MJ (2013). Missed office visits and risk of mortality among HIV-infected subjects in a large healthcare system in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 27(8), pp. 442–449. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0073 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23869466http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1089/apc.2013.0073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiamsakul A, Kumarasamy N, Ditangco R, Li PC, Phanuphak P, Sirisanthana T, … Study, T. A. S. t. E. R. M. (2014). Factors associated with suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Asia. J Int AIDS Soc, 17(1), p 18911. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18911 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24836775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mburu G, Paing AZ, Myint NN, Di W, Thu KH, Ram M, … Naing S. (2016). Retention and mortality outcomes from a community-supported public-private HIV treatment programme in Myanmar. J Int AIDS Soc, 19(1), p 20926. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20926 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27784509https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5081489/pdf/JIAS-19-20926.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus H, Petoumenos K, Brown K, Baker D, Russell D, Read T, … Australian, H. I. V. O. D. (2015). Loss to follow-up in the Australian HIV Observational Database. Antivir Ther, 20(7), pp. 731–741. doi: 10.3851/IMP2916 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25377928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megerso A, Garoma S, Eticha T, Workineh T, Daba S, Tarekegn M, & Habtamu Z. (2016). Predictors of loss to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment for adult patients in the Oromia region, Ethiopia. HIV AIDS (Auckl), 8, pp. 83–92. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S98137 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27175095https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=30054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Westfall AO, Crane HM, Zinski A, Willig JH, … Saag MS. (2012). Early retention in HIV care and viral load suppression: implications for a test and treat approach to HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 59(1), pp. 86–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318236f7d2 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21937921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Cole SR, Geng EH, Crane HM, Kitahata MM, … for the Centers for, A. R. N. o. I. C. S. (2014). Beyond Core Indicators of Retention in HIV Care: Missed Clinic Visits Are Independently Associated With All-Cause Mortality. Clin Infect Disdoi: 10.1093/cid/ciu603 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25091306http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/08/28/cid.ciu603.full.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer CM, Bott S, Carrieri P, Parsons M, Pulerwitz J, Rutenberg N, & Sarna A. (2009). HIV testing, treatment and prevention: generic tools for operational research. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlis B, Burchell AN, Gardner S, Light L, Raboud J, Antoniou T, … Ontario, H. I. V. T. N. C. S. (2016). Social determinants of health and retention in HIV care in a clinical cohort in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Care, pp. 1–10. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1271389 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28027668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAHOD. (2016). A Decade of Combination Antiretroviral Treatment in Asia: The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database Cohort. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 32(8), pp. 772–781. doi: 10.1089/AID.2015.0294 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27030657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran DA, Ngo AD, Shakeshaft A, Wilson DP, Doran C, & Zhang L. (2013). Trends in and determinants of loss to follow up and early mortality in a rapid expansion of the antiretroviral treatment program in Vietnam: findings from 13 outpatient clinics. PLoS One, 8(9), p e73181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073181 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24066035http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3774724/pdf/pone.0073181.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawrzyniak AJ, Rodriguez AE, Falcon AE, Chakrabarti A, Parra A, Park J, … Metsch LR (2015). Association of individual and systemic barriers to optimal medical care in people living with HIV/AIDS in Miami-Dade County. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 69 Suppl 1, pp. S63–72. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000572 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25867780https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4560198/pdf/nihms661264.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward B, Person A, Rebeiro P, Kheshti A, Raffanti S, & Pettit A (2015). Risk Prediction Tool for Medical Appointment Attendance Among HIV-Infected Persons with Unsuppressed Viremia. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 29(5), pp. 240–247. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0334 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25746288http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1089/apc.2014.0334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Zhu H, Wu Y, Dou Z, Zhang Y, Kleinman N, … Shang H. (2014). HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus co-infection in patients in the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program, 2010–12: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis, 14(11), pp. 1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70946-6 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25303841http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1473309914709466/1-s2.0-S1473309914709466-main.pdf?_tid=9ebc860a-dc4a-11e6-ae81-00000aacb360&acdnat=1484612553_e59e82320f3ed2cbadaa1213c617f83c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Dou Z, Sun K, Ma Y, Chen RY, Bulterys M, … Zhang F. (2012). Association between missed early visits and mortality among patients of china national free antiretroviral treatment cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 60(1), pp. 59–67. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824c3d9f Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22517414http://graphics.tx.ovid.com/ovftpdfs/FPDDNCJCHGLBFE00/fs047/ovft/live/gv024/00126334/00126334-201205010-00009.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Kumarasamy N, Ditangco R, Kamarulzaman A, Lee CK, Li PC, … Database, T. A. H. O. (2005). The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database: baseline and retrospective data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 38(2), pp. 174–179. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15671802http://graphics.tx.ovid.com/ovftpdfs/FPDDNCLBLGOOLA00/fs047/ovft/live/gv024/00126334/00126334-200502010-00008.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Tanuma J, Chaiwarith R, Lee CK, Law MG, Kumarasamy N, … Lim PL. (2012). Loss to Followup in HIV-Infected Patients from Asia-Pacific Region: Results from TAHOD. AIDS Res Treat, 2012, p 375217. doi: 10.1155/2012/375217 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22461979http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3296146/pdf/ART2012-375217.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]