Abstract

Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool (HEART) is a tool developed by the World Health Organization whose objective is to provide evidence on urban health inequalities so as to help to decide the best interventions aimed to promote urban health equity. The aim of this paper is to describe the experience of implementing Urban HEART in Barcelona city, both the adaptation of Urban HEART to the city of Barcelona, its use as a means of identifying and monitoring health inequalities among city neighbourhoods, and the difficulties and barriers encountered throughout the process. Although ASPB public health technicians participated in the Urban HEART Advisory Group, had large experience in health inequalities analysis and research and showed interest in implementing the tool, it was not until 2015, when the city council was governed by a new left-wing party for which reducing health inequalities was a priority that Urban HEART could be used. A provisional matrix was developed, including both health and health determinant indicators, which allowed to show how some neighbourhoods in the city systematically fare worse for most of the indicators while others systematically fare better. It also allowed to identify 18 neighbourhoods—those which fared worse in most indicators—which were considered a priority for intervention, which entered the Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods programme and the Neighbourhoods Plan. This provisional version was reviewed and improved by the Urban HEART Barcelona Working Group. Technicians with experience in public health and/or in indicator and database management were asked to indicate suitability and relevance from a list of potential indicators. The definitive Urban HEART Barcelona version included 15 indicators from the five Urban HEART domains and improved the previous version in several requirements. Several barriers were encountered, such as having to estimate indicators in scarcely populated areas or finding adequate indicators for the physical context domain. In conclusion, the Urban HEART tool allowed to identify urban inequalities in the city of Barcelona and to include health inequalities in the public debate. It also allowed to reinforce the community health programme Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods as well as other city programmes aimed at reducing health inequalities. A strong political will is essential to place health inequalities in the political agenda and implement policies to tackle them.

Keywords: Urban health, Social determinants of health, Public health surveillance, Health status indicators, Health policy, Health inequalities, Small-area analysis

Introduction

Social inequalities are the result of the different opportunities and resources related to health that people have depending on their social class, gender, territory or ethnic group, which results in worse health among less privileged social groups [1, 2]. In order to tackle these inequalities, a public health surveillance system is needed to monitor them across different areas or different time periods [3].

Urban HEART (Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool) is a tool developed by the World Health Organization (the WHO Kobe Centre) whose objective is to provide evidence on urban health inequalities so as to help to decide the best interventions aimed to promote urban health equity. An Urban HEART ad-hoc advisory group made up of 12 members worldwide, including one member from the Public Health Agency of Barcelona (ASPB, for its initials in Catalan), provided expert advice. Its recommendations are included in the Urban HEART Guide and User Manual [4, 5]. The Urban HEART can be used to identify and monitor health inequalities, using the Urban HEART matrix and monitor. However, it should not be exclusively used to generate evidence on health inequalities. The response component of the tool is intended to be included in the local planning and implementation cycle so as to ensure linkage with sectors outside the health sector, inclusion of health equity issues in the political debate and adequate budget allocation. The tool was pilot-tested in 15 cities from 10 low-middle income countries [6–10]. To our knowledge, the only city from a high-income country to have used it previous to Barcelona has been Toronto (Canada) [11].

Barcelona, the second largest Spanish urban area, is located on the Eastern coast and made up of more than 1.6 million inhabitants, of which 21.6% are 65 years and older and 22.3% are foreign-born. Like any large urban area, Barcelona has noteworthy social heterogeneity, with high level of welfare areas coexisting with pockets of poverty and marginalization areas. Since the first democratic elections in 1979 and until 2011, the city of Barcelona has been governed by a coalition of left-wing parties led by the Socialist Party, for which public health was a priority. As an example of this priority, geographical health information systems were established, which progressively focussed in the small areas of the city, the Barcelona Health Survey was implemented in 1983 (the first undertaken in Spain) and the health report of the citizens of Barcelona was annually published. All these advances allowed to identify intra-urban socioeconomic health inequalities [12]. The ASPB has broad experience in the study and monitoring of social health inequalities. During the 1980s, research on social health inequalities focused on the study of mortality indicators across the 10 municipal districts (around 100,000 inhabitants) [13, 14]. Later, in the 1990s and later, inequalities were analysed at smaller areas such as neighbourhoods or basic health areas (around 20,000 inhabitants), and for other health outcomes such as AIDS, tuberculosis, drug consumption or teenage pregnancies [15–24]. With the advance of health information systems and methods of analysis, some research projects (MEDEA and INEQ-CITIES) allowed to perform small-area analysis (census tracts of around 1000 inhabitants) [25–28].

The ASPB has also taken part in implementing several interventions to tackle such health inequalities [29], such as the mother and child health programme in the district of Ciutat Vella aimed to reduce inequalities in infant mortality [30], the tuberculosis control among most disadvantaged populations [31, 32], the drug abuse programmes [33] and the reform of primary health care which started in the poorest areas of the city [34]. Also, the “Neighbourhoods Law” began in 2004, an urban renewal programme focused on the most deprived neighbourhoods [35], which was accompanied by the “Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods” programme, whose objective was to reduce inequalities in health by implementing specific interventions in those neighbourhoods [36]. However, although this programme has been ongoing, it has not been until 2015, when the city was governed by a new left-wing party made up of left-wing parties and social movements such as the 15M that it was relaunched with an important resource increase.

The aim of this paper is to describe the experience of implementing Urban HEART in Barcelona city, both the adaptation of the tool and its use as a means of identifying and monitoring health inequalities among city neighbourhoods, as well as the difficulties and barriers encountered throughout the process.

The Political Prioritization of Health Inequalities in Barcelona

After Urban HEART was launched in 2010, the WHO Kobe Centre was interested in having a European country implementing it. At that moment, Barcelona was governed by a coalition of three left-wing parties, which allowed to use Urban HEART but only as a diagnosis tool, without assigning any specific budget aimed at implementing interventions focused on reducing health inequalities more than that assigned to those already ongoing. Since several inequalities diagnosis tools had already been used through the years at the ASPB, the department in charge of developing the Urban HEART decided to postpone its implementation until the response phase was also prioritized and budgeted. In 2011, a nationalist right-wing party won the elections and governed until 2015. During this period, health inequalities were not a political priority and Urban HEART was not an option. Finally, in 2015, a new left-wing coalition party won the elections, prioritized reducing health inequalities in the city [37] and required the ASPB to immediately publish the Urban HEART so as to implement interventions in the most deprived neighbourhoods. The new city council considered the Urban HEART as an adequate tool to decide those neighbourhoods in most need for intervention based on the evidence on health and health determinant inequalities provided by the tool.

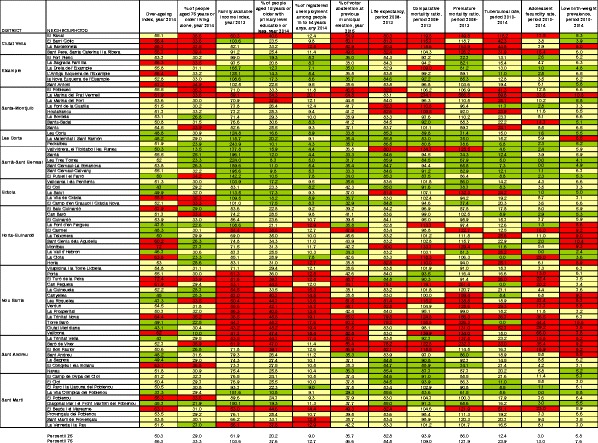

The political opportunity to publish Urban HEART Barcelona and a tight time schedule to include it in the forthcoming Barcelona Health Report, one of the ASPB reports with higher mass media impact, resulted in the development of a provisional Urban HEART matrix for which the selection of indicators was based only on readily available data sources and without an in-depth analysis of the indicator requirements indicated in the Urban HEART guidelines. This provisional version included 12 indicators (6 health and 6 health determinant indicators) (see Table 1) for the 73 city neighbourhoods (ranging 550 to 57,000 inhabitants; mean = 22,000) and used percentiles 25 and 75 as objective and standard of comparison for all indicators. All health indicators were calculated for 5-year periods so as to reduce variability of point estimations at the neighbourhood level. The provisional matrix (Fig. 1) allowed to show how some neighbourhoods in the city fare worse (red in the matrix) for most of the indicators, mainly those in the North, North-East, South and South-East of the city (the lower income neighbourhoods in the city), while others fare better (green in the matrix), mainly those in the West of the city (the higher income neighbourhoods). Those neighbourhoods with worse socioeconomic indicators also showed worse health indicators.

Table 1.

Indicators included in the provisional and final versions of Urban HEART Barcelona

| Urban HEART domains | Provisional version | Final version |

|---|---|---|

| Health | Life expectancy | Premature mortality rate |

| Comparative mortality ratio | Tuberculosis rate | |

| Comparative premature mortality ratio | Gonococcal rate | |

| Tuberculosis rate | Teenage fecundity rate | |

| Teenage fecundity rate | Problematic drug consumption indexc | |

| Low birth-weight prevalence | ||

| Physical environment and infrastructure | – | Neighbourhood area allocated to urban parks and gardens (%) |

| Vegetation index (NDVI)d | ||

| Vehicle-km travelled | ||

| Social and human development | People aged 15 years or older with primary level education or less (%) | Ratio % of housing with > 4 residents per housing mean area |

| Over-ageing indexa | Rate of people assisted by Social Services excluding those attributable to the Dependency Law | |

| People aged 75 years or older living alone (%) | Rate of people aged 17 years and younger assisted by the Child and Teenage Assistance Team | |

| People 16 to 29 years old with primary level education or less (%) | ||

| Economics | Family available income indexb | Family available income indexb |

| Registered unemployment among people aged 16 to 64 years (%) | Registered unemployment among people aged 16 to 64 years (%) | |

| Governance | Voter abstention in the previous municipal elections (%) | Voter abstention in the previous municipal elections (%) |

aProportion of people aged 75 years or older over the number of people aged 65 years or older

bCompound index that reflects the distribution of the neighbourhood mean family income compared to the city mean and that includes 5 indicators (people aged 25 years or more with university level education (%), registered unemployment among people aged 16 to 64 year (%), number of cars per inhabitant, new cars (less than 2 years) with more than 16 hp (%) and second-hand housing prices)

cCompound index that includes 4 indicators related to drug consumption (rate of new treatments due to drug consumption, mortality rate due to drug overdose, rate of emergency visits among drug consumers, number of syringes found on the street)

dNormalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), indicator that reflects the amount of vegetation by assessing the amount of green observed from a satellite picture

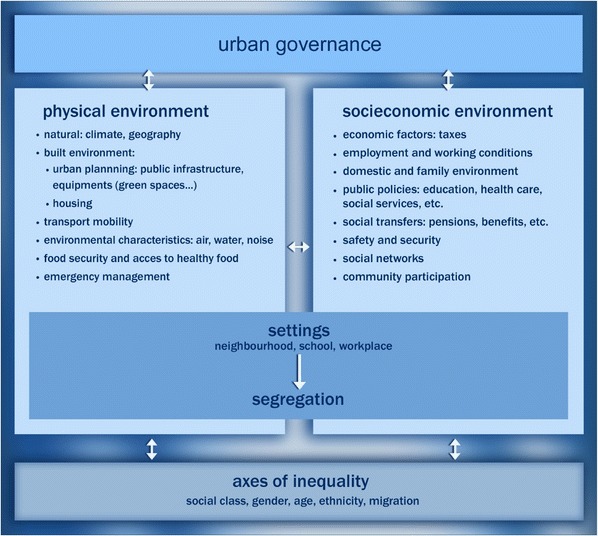

Fig. 2.

Determinants of health inequalities in urban areas [41]

The matrix was also used to identify those neighbourhoods with a high priority for intervention to reduce health inequalities in the city. An index was created by assigning a value to each matrix colour (1.5 points for red, 1 points for yellow and 0.5 points for green cells), following the Hanlon methodology [38], and adding the values of every indicator in each neighbourhood. The index allowed to identify 18 neighbourhoods (those in the worst index quartile) which were considered a priority for intervention. Both the provisional matrix and the neighbourhood prioritization were included in the 2014 Barcelona Health Report [39] and given high visibility. The issue had important repercussion in the media.

The Use of Urban HEART Barcelona as a Response Tool

The prioritized neighbourhoods entered the ASPB programme Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods, in 11 of which the programme was already ongoing and it was reinforced. In the seven remaining neighbourhoods, the programme was implemented. The city council assigned a specific budget for the ASPB programme Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods (300,000 €) as well as for the Neighbourhoods Plan (150 million €) to act upon the most deprived Barcelona neighbourhoods so as to reduce health and social inequalities. The objective of the Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods programme, ongoing since 2007, is to reduce health inequalities between Barcelona neighbourhoods through a community-action strategy and consists in the implementation of public health interventions based on the results of health needs and health assets report. Both quantitative and qualitative data are collected in the report. The local community participates both providing information to the report by means of in-depth interviews and taking part of the neighbourhood steering group. The report is followed by a participatory prioritization of health needs and the specific interventions are decided based on available scientific evidence of their effectiveness, always taking into consideration community priorities and preferences, as indicated in the Urban HEART Manual. The Neighbourhoods Plan also addresses urban infrastructure, economic and employment issues, among others.

Currently, all the prioritized neighbourhoods already had, or are currently working in, a comprehensive participatory diagnosis process, community prioritization of needs and assets, community working groups and community development activities. In 2016, Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods facilitated 25 new community working groups in 15 of the prioritized neighbourhoods, and 16 new programmes were implemented [40]. Additionally, Neighbourhoods Plan has started to implement urban regeneration interventions (urban planning, neighbourhoods’ facilities, housing renewal) and occupational projects.

Revision of Urban HEART Barcelona

The provisional version of Urban HEART Barcelona was reviewed so that it better complied with the requirements specified in the Urban HEART user manual, such as efficiency (the provisional version had three mortality indicators) or actionable indicators (the over-ageing index and people 75 years and over living alone did not comply with this requirement). With this objective, the Urban HEART Barcelona Working Group (UHB Working Group) was created, which was composed of technicians working at different departments of the ASPB, and therefore with in-depth experience on several public health issues, as well as other institutions and organizations in the city working in the areas of social services, statistics (which generate economic and demographic indicators, among others) or environment and urbanism. The selection of Urban HEART Barcelona indicators was carried out in four stages.

Stage 1. Identification of available indicators

Based on the urban health determinants and inequalities framework (Fig. 2) [41] and the Urban HEART policy domains specified in the Urban HEART user manual (health, physical environment and infrastructure, social and human development, economics and governance), available indicators at the neighbourhood level and obtained from routine sources of information were searched for. The UHB Working Group defined a list of potential indicators which had to meet the following criteria: (1) data representative at the neighbourhood level; (2) enough data variability to capture inequalities; (3) data quality and validity; (4) obtained from routine data sources. Indicators were classified according to the Urban HEART domains. Thirty-seven indicators were identified, 11 of which were health status indicators and 26 health determinants indicators (Table 2). Forty-nine percent of these indicators were elaborated in institutions other than the ASPB (social services, education, ecology, among others). In order to guarantee representativeness at the neighbourhood level, the UHB Working Group decided to calculate most health indicators using period-aggregated data instead of yearly data. A 3-year period was chosen instead of a 5-year period (used in the provisional version) to facilitate capturing changes of the indicators in time (responsiveness requirement). Overall rates were chosen instead of sex-, age- or other inequality axis-specific rates.

Stage 2. Indicator selection and scoring

Fig. 1.

Urban HEART Barcelona matrix, provisional version, year 2014

Table 2.

Indicators’ suitability and relevance scores. Results from the online survey

| Suitability | Relevance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | NR/DK | Percent* | Mean (SD) | |

| Health domain | |||||

| Life expectancy | 35 | 2 | 0 | 94.6 | 8.9 (1.1) |

| Comparative mortality rate | 26 | 7 | 4 | 78.8 | 7.5 (1.2) |

| Comparative premature mortality rate | 30 | 5 | 2 | 85.7 | 8.1 (1.0) |

| Tuberculosis rate | 31 | 2 | 4 | 93.9 | 7.7 (1.4) |

| HIV rate | 28 | 5 | 4 | 84.8 | 7.8 (1.4) |

| Gonococcal rate | 22 | 6 | 9 | 78.6 | 7.5 (1.4) |

| Teenage fecundity rate | 33 | 2 | 2 | 94.3 | 7.9 (1.3) |

| Low birth-weight prevalence | 25 | 5 | 7 | 83.3 | 7.1 (1.8) |

| Problematic Drug Consumption Indexa | 33 | 3 | 1 | 91.7 | 8.0 (1.2) |

| Traffic-injured people by vehicle-km travelled ratio | 20 | 10 | 7 | 66.7 | 7.0 (1.5) |

| Traffic-injured people by road length ratio | 16 | 10 | 11 | 61.5 | 6.6 (1.8) |

| Mental disability prevalence | 21 | 10 | 6 | 67.7 | 7.1 (1.3) |

| Physical environment and infrastructure domain | |||||

| Neighbourhood area allocated to urban parks and gardens (%) | 32 | 4 | 1 | 88.9 | 7.5 (1.3) |

| Vegetation index (NDVI)b | 20 | 5 | 12 | 80.0 | 7.5 (1.5) |

| Vehicle-km travelled | 20 | 14 | 3 | 58.8 | 7.3 (1.5) |

| Residents living close to public transportation (%) | 25 | 9 | 3 | 73.5 | 7.4 (1.7) |

| Adequately accessible streets (%)c | 23 | 8 | 6 | 74.2 | 7.4 (1.9) |

| Neighbourhood area allocated to road network (%) | 21 | 12 | 4 | 63.6 | 6.4 (2.3) |

| Ratio of educational equipment for those aged 17 years and younger | 27 | 8 | 2 | 77.1 | 7.4 (1.9) |

| Participation equipment per inhabitant ratio | 26 | 7 | 4 | 78.8 | 6.7 (2.3) |

| Play area equipment per inhabitant ratio | 25 | 5 | 7 | 83.3 | 7.5 (1.5) |

| Social and human development domain | |||||

| Ratio % of housing with > 4 residents per housing mean area | 31 | 4 | 2 | 88.6 | 7.5 (1.4) |

| Rate of people assisted by Social Services | 28 | 5 | 4 | 84.8 | 7.4 (1.5) |

| Rate of new people assisted by Social Services | 29 | 6 | 2 | 82.9 | 7.6 (1.6) |

| Rate of people assisted by Social Services with a community kitchen prescription | 25 | 7 | 5 | 78.1 | 7.8 (1.4) |

| Rate of people aged 17 years and younger assisted by the Child and Teenage Assistance Team | 32 | 3 | 2 | 91.4 | 7.8 (1.5) |

| People 16 to 29 years old with primary level education or less (%) | 37 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 | 8.4 (1.2) |

| People 25 to 34 years old with college education or more (%) | 31 | 6 | 0 | 83.8 | 7.5 (1.2) |

| Over-ageing indexd | 29 | 6 | 2 | 82.9 | 8.1 (1.3) |

| Foreign-born, excluding those from developed countries (%) | 27 | 5 | 5 | 84.4 | 7.8 (1.4) |

| People aged 75 years or older living alone (%) | 35 | 2 | 0 | 94.6 | 8.0 (5.0) |

| Economics | |||||

| Family available income indexe | 34 | 2 | 1 | 94.4 | 8.9 (1.1) |

| Registered unemployment among people aged 16 to 64 years (%) | 37 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 | 8.7 (1.3) |

| Rate of people aged 65 years or older with a non-contributory retirement pension | 32 | 3 | 2 | 91.4 | 7.5 (1.5) |

| People aged 60 years or older with an income < 1IPREM (%) | 28 | 4 | 5 | 87.5 | 8.0 (1.6) |

| Rate of people assisted by Social Services with an economic aid | 28 | 4 | 5 | 87.5 | 7.7 (1.8) |

| Governance | |||||

| Voter abstention in the previous municipal elections (%) | 25 | 6 | 6 | 80.6 | 7.2 (1.5) |

NR/DK no response/do not know, IPREM reference index used as the income threshold to receive different types of assistance

*Calculated excluding NR/DK responses

aCompound index that includes 4 different indicators related to drug consumption

bNormalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), indicator that reflects the amount of vegetation by assessing the amount of green observed from a satellite picture

cDefined as having a sidewalk width of ≥ 2.5 m on one side and of ≥ 1.8 m on the other side and < 6% sidewalk slope

dProportion of people aged 75 years or older over the number of people aged 65 years or older

eCompound index that attempts to reflect the neighbourhood mean family income

Following a similar methodology as that used in Toronto [11], technicians with experience in public health and/or in indicator and database management were invited to participate in an online survey in which they were asked to (1) indicate if suggested indicators met with established requirements (Table 3) and to (2) score them (1 to 10) according to indicator relevance for the city of Barcelona in terms of health and social inequalities. Participants were provided with a brief explanation of the Urban HEART and some instructions on how to answer the survey, as well as a technical datasheet which included, for each indicator, a text description along with a series of statistics, graphs and maps. Thirty-seven technicians participated in the online survey (92.5% response rate). Table 2 shows suitability and relevance of suggested indicators according to respondents. Across all domains, most indicators showed suitability proportions of 80% or more and a relevance score of 7.5 or higher. The physical environment and infrastructure domain was the one with the lowest suitability proportions and relevance scores, as well as traffic-related indicators.

Stage 3. Definitive selection of indicators

Table 3.

List of indicator requirements used for indicator selection and scoring

| Requirement | Description |

|---|---|

| Clear | Easy to understand and interpret |

| Actionable | Sensitive to changes derived from policy interventions |

| Responsive | Can show changes in a timely manner |

| Comparable | Can be compared in time and among areas |

| Analytically sound | Well-grounded in theory and in fact |

| Meaningful for Barcelona | Points to health and health determinant’s issues relevant for the city of Barcelona |

The UHB Working Group decided the definitive list of indicators that would be included in the definitive version of Urban HEART Barcelona based on the survey results and on a working group discussion in which the following aspects were taken into consideration: (1) a limited number of indicators should be selected; (2) efficiency: no redundancies should exist among the indicators; (3) exhaustivity: indicators should measure the different health determinants; (4) indicators should allow inequality monitoring follow-up. The definitive version of Urban HEART Barcelona included 15 indicators (see Table 1). Premature mortality was chosen instead of life expectancy because it better complied with the responsive requirement. The vehicle-km indicator, despite its low suitability according to survey results, was also included in the physical environment and infrastructure domain since the working group considered that it can approximate to pollution, an important health determinant for which no information is available at the neighbourhood level. The over-ageing index, the proportion of foreign-born (excluding those from developed countries) and the proportion of people aged 75 years or older living alone were excluded since they were considered to be descriptive of the neighbourhood population and not actionable. With regard to the voter abstention indicator, the UHB Working Group considered that its ability to capture citizen political participation was rather limited and its availability every 4 years was an important limitation. However, it was finally included since no other indicators were identified in the governance domain. In addition, the working group decided that, for those neighbourhoods with less than 3000 inhabitants (6 out of 73 neighbourhoods), all health indicator estimations (with the exception of the drug consumption index, which was not subject to small number issues) would be replaced with that of neighbourhood of the city district with a similar income index. Finally, it was decided that calculating health indicators for 3- instead of 5-year periods would improve the responsive requirement and would have little impact on the variability of point estimations at the neighbourhood level.

Stage 4. Selection of indicators’ objective and standard of comparison

A search of the literature was carried out to identify national, regional or local objectives for each of the indicators, although no clear cut-off values were identified. Also, different alternatives using internal Barcelona data (statistics such as percentiles, mean, and others) were taken into consideration. After trying different cut-off points, the UHB Working Group decided to use the 25 and 75 percentiles of each indicator, as had been done in the provisional version.

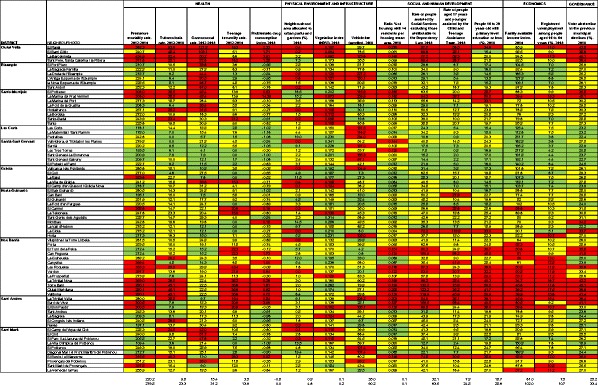

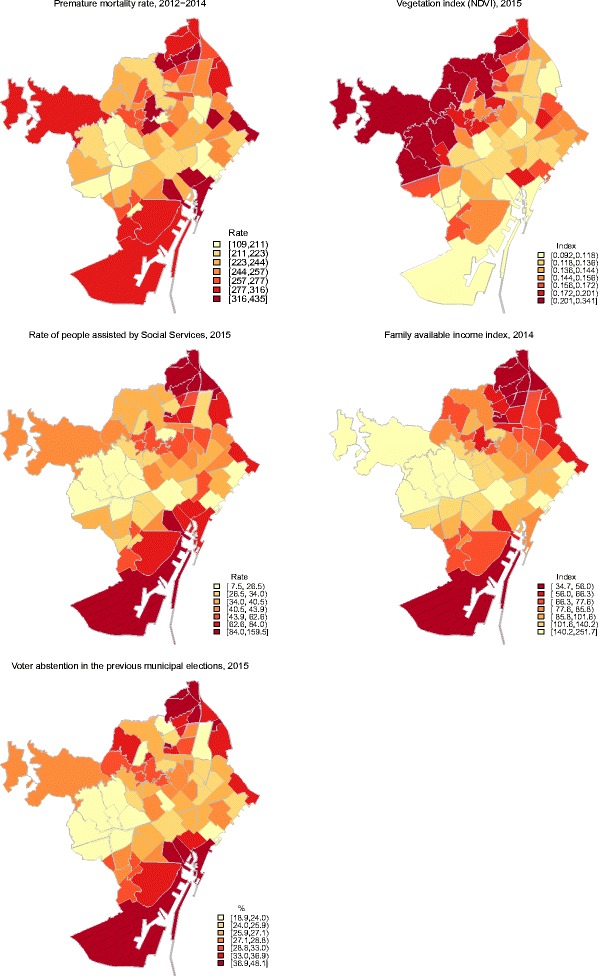

The definitive version of the Urban HEART Barcelona matrix is shown in Fig. 3, and one indicator from each domain has been mapped (Fig. 4). Although more than half of the indicators had changed in the new matrix, results were similarly to those observed with the provisional version (i.e., the neighbourhoods which fared worse and better were the same). However, four indicators showed a different behaviour. Red cells for gonococcal rates were concentrated mainly in the South-East and in the centre of the city, neighbourhoods with a larger proportion of men that have sex with men. All three physical environment and infrastructure domain indicators also showed a different pattern, being red cells distributed more heterogeneously, and some of which even concentrated in better performing neighbourhoods, as in the case of the vehicle-km travelled indicator. The distribution of these indicators seems to reflect differences in the urban compactness level and in mobility patterns across the city neighbourhoods more than differences in socioeconomic characteristics.

Fig. 3.

Urban HEART Barcelona matrix, definitive version, year 2015

Fig. 4.

Neighbourhood distribution of five of the Urban HEART matrix indicators

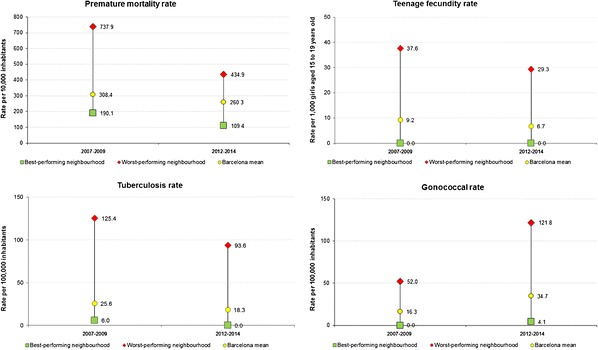

The definitive version of Urban HEART Barcelona was used to attempt to analyse inequalities trend. The Urban HEART Monitor was applied to those indicators from the health domain for which information was available 5 years previously (Fig. 5). Premature mortality rate, teenage fecundity rate and tuberculosis rate indicators showed a reduction of inequalities as well as an improvement of the indicator at the city level. On the contrary, the gonococcal rate indicator showed an inequality increase as well as a worsening of the indicator at the city level.

Fig. 5.

Urban HEART Barcelona monitor for premature mortality rate, teenage fecundity rate, tuberculosis rate and gonococcal rate indicators

Discussion

The implementation of Urban HEART in Barcelona had to overcome several difficulties, most importantly the lack of political will to tackle socioeconomic inequalities in health. Although the ASPB had participated in the Urban HEART Advisory Group and its public health technicians had large experience on health inequalities, implementation of Urban HEART Barcelona was not possible until 2015, when the city was governed by a new left-wing political party based on social movements which had reducing health inequalities as a political priority. The fact that several public health technicians took part in developing the electoral programme and that the city council health commissioner belonged to the political party at government (which was not the case in the left coalition that governed the city prior to 2011) might have helped implementing Urban HEART in Barcelona. Available evidence shows that, although most politicians are aware of health inequalities and their social causes, their inclusion in the political agenda is unusual [42, 43]. These studies and the experience in Barcelona show that strong political will is needed to place socioeconomic health inequalities in the municipal government’s agenda and in city plans.

The provisional version of Urban HEART Barcelona matrix allowed to confirm the presence of inequalities among Barcelona neighbourhoods, results which were also confirmed with the definitive version of the matrix. The tool highlights the presence of inequalities in health and its determinants, which can help including health inequalities in the public debate, and therefore in the political agenda [43]. The fact that the matrix includes not only health indicators but also their social determinants can highlight the need for a Health in All Policies approach to tackle health inequalities [44]. However, in Barcelona, information collected by the tool was considered insufficient to decide the best interventions to tackle inequalities. Instead, a more in-depth analysis of the situation including a larger number of indicators was believed necessary.

Although not included in the Urban HEART User Manual, in Barcelona, an index summarizing Urban HEART matrix was developed to perform neighbourhood prioritization, which was required by the city government to guide the political action in the 2016–2019 period. A similar methodology was used in Toronto with the objective of facilitating the interpretation of the wealth of information included in the matrix [11]. Similarly, the New York City Equality Indicators Project [45] summarizes 96 health and health determinant indicators in a static and a dynamic score across six thematic areas with the purpose of capturing change over time in progress towards equality. If the Urban HEART Advisory Group considered an index calculation as of interest for Urban HEART, it would be desirable to include advice on the recommended methodology in the user manual. In Barcelona, the index allowed to prioritize 18 neighbourhoods in most need, among which the Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods programme and the Neighbourhoods Plan were implemented. Assessment of the reduction of health inequalities following the implemented interventions will be necessary.

The definitive version of Urban HEART Barcelona improved the previous version in several requirements, including efficiency (only one of the three mortality-related indicators included in the provisional version was chosen), exhaustivity (all domains included one or more indicators, including the physical environment and infrastructure domain, in which no indicators had been included in the provisional version) and actionability (non-actionable indicators were removed, such as over-ageing index and people 75 years and over living alone). This version will allow for a better follow-up of health inequalities in the city of Barcelona. In addition, the development of this version allowed to engage with sectors other than health, which can contribute to increase the understanding of health inequalities and their social causes among technicians and officers [42].

Some barriers were encountered during the adaptation of Urban HEART Barcelona. For instance, working at the neighbourhood level implied having to estimate indicators in some areas with a small population. The UHB Working Group decided to overcome this issue by replacing the values of scarcely populated neighbourhoods with that from a similar neighbourhood. Also, 3-year-period indicators were calculated to reduce variability in the estimations while trying to minimize the impact on the responsiveness requirement. Alternative solutions could also be useful, such as estimating indicators using Bayesian methods [46]. Given that this situation is most probably common across many cities, advice from the Urban HEART Advisory Group on this issue would be desirable. Another barrier was the difficulty in finding adequate physical context indicators at the neighbourhood level available periodically. Many relevant indicators, such as air pollution or housing, were not available at the neighbourhood level. Although some adequate quality indicators were identified, most had to be discarded since they were not based on routine data or were census-based, which in Spain is only carried out every 10 years and for which the later edition was sample-based. Others based on routine data, such as air pollution, were only available at the city level. However, changes in time among physical context indicators are expected to be small or negligible, and several follow-up years will be necessary to detect significant changes in this type of indicators. The Urban HEART Advisory Group should reconsider if annual periodicity of physical context indicators is necessary or a larger periodicity could be sufficient. Data availability was also a barrier in other domains, such as the health domain, for which no mental health indicator other than drug consumption was available periodically at the neighbourhood level and none of the healthcare-based data could be considered, since healthcare divisions are not based on neighbourhood but rather on Basic Health Areas (ABS for its initials in Spanish). With respect to indicator selection, the UHB Working Team had doubts regarding what type of inequalities had to be considered when designing the Urban HEART. The user manual only specifies that socioeconomic inequalities have to be taken into account, from which it can be derived that any inequality axis could be considered. The gonococcal rate included in the Barcelona Urban HEART in fact reflects inequalities by sexual option, since half of gonorrhoea cases correspond to men who have sex with men [47]. The group discussed whether or not this indicator should be included, since the remaining indicators are mostly explained by income inequalities, and finally decided its inclusion because adding another inequality axis to the matrix was perceived as an added value.

Regarding health inequalities monitoring, Urban HEART User Manual recommends the use of the Urban HEART Monitor, which depicts the two neighbourhoods with the worst and best values for an indicator, as well as the city mean and the indicator’s benchmark and standard of comparison. However, this methodology has some limitations. Mainly, that it focuses exclusively on two neighbourhoods. First, this does not take into consideration the remaining neighbourhoods when monitoring health inequalities. In addition, changes could be more attributable to the instability of point estimations than to real changes in the indicator at the neighbourhood level, especially among scarcely populated neighbourhoods. It would be advisable that additional inequality measures [48] would be included in the user manual, including both absolute and relative measures. Given that significant changes in the indicators cannot be expected in the short term and the instability in the point estimations at the neighbourhood level, advice on the periodicity with which inequalities should be measured would also be desirable to be included in the user manual.

There are other health inequality monitoring experiences, such as the Health Equity Monitor from the WHO Global Health Observatory [49] or the Health Inequalities Interactive Tool [50] or the Health Profiles online tool published by Public Health England [51]. In the ASPB, which has a long history of analysing intra-city health inequalities, its annual Health Report and other health reports show health indicators stratified by gender, country of origin or educational attainment, among other inequality axes. Small-area level analysis, beyond what has been done in research studies, has been incorporated recently in inequality analysis at the ASPB. As an example, InfoBarris is an online platform which displays 64 health and health determinants indicators for each of the 73 Barcelona city neighbourhoods, through graphics, maps and tables, with the objective of facilitating health surveillance at the neighbourhood level [52]. Similar platforms have been developed abroad, such as that in the King County in the USA [53]. Compared to all these tools, the Urban HEART summarizes health inequalities in only one figure (i.e., the matrix), which shows both health and health determinant inequalities in a simple and easy to interpret way. In the case of Barcelona, Urban HEART Barcelona only focuses on the neighbourhood as the disaggregation variable, without considering other inequality axes. However, the Barcelona Council, in collaboration with the ASPB, is also working in developing a Health Inequalities Observatory, which will take into consideration other inequality axes, as well as health inequalities monitorization.

Conclusions

Implementation of Urban HEART in Barcelona was only possible when the municipal council was governed by a political party for which health inequalities are a priority, and which budgeted interventions to attempt to reduce them. Therefore, tackling health inequalities requires not only being aware of such inequalities but also a strong political will.

The Urban HEART allowed to identify urban inequalities in the city of Barcelona, to prioritize those neighbourhoods in most need, as well as to include health inequalities in the public debate. The way this tool depicts indicators’ results, in a very simple and visual way, facilitates understanding and highlighting health inequalities and its social causes among a non-expert audience. It also allowed to reinforce the community health programme Health in the Barcelona Neighbourhoods as well as other city programmes aimed at reducing health inequalities.

The revision of Urban HEART Barcelona allowed to refine the indicators included to better comply with the established requirements, and it also allowed to widen the number and type of stakeholders involved and familiar with Urban HEART and with health inequalities, which can make health equity interventions easier to implement at the local level.

Acknowledgements

Urban HEART Barcelona Working Group (in alphabetical order): M. Jesús Calvo, Berta Cormenzana, Imma Cortés, Èlia Diez, Cynthia Echave, Albert Espelt, Patrícia G. de Olalla, Josep Gòmez, Ana M. Novoa, Montserrat Pallarès, Glòria Pérez, Maica Rodríguez-Sanz

References

- 1.Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429–445. doi: 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B. State of the art in research on equity in health. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2006;31(1):11–32. doi: 10.1215/03616878-31-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espelt A, Continente X, Domingo-Salvany A, et al. La vigilancia de los determinantes sociales de la salud. Gac Sanit. 2016;30:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Urban HEART: urban health equity assessment and response tool: user manual. Kobe: World Health Organization; 2010.

- 5.World Health Organization. Urban HEART: urban health equity assessment and response tool. Kobe: World Health Organization; 2010.

- 6.Basweti Nyasani I. Kenya’s experience on urban health issues. Final report on the Urban HEART pilot-testing project. http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/measuring/urbanheart/nakuru_urbanheart_city_report.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed 2 Dec 2016.

- 7.Socorro De Los Santos M. Report on documentation and evaluation of Urban HEART pilot in the Philippines. 2013. http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/publications/Philippines.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

- 8.Prasad A, Kano M, Dagg KAM, et al. Prioritizing action on health inequities in cities: an evaluation of Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool (Urban HEART) in 15 cities from Asia and Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad A, Groot AM, et al. Linking evidence to action on social determinants of health using Urban Heart in the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;34(6):407–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asadi-lari M, Vaez-mahdavi MR, Faghihzadeh S, et al. The application of urban health equity assessment and response tool (Urban HEART) in Tehran; concepts and framework. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2010;24(3):175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centre for Research in Inner City Health Toronto. Urban HEART @Toronto: technical report/user guide. Toronto; Centre for Research in Inner City Health Toronto; 2014.

- 12.Borrell C, Bartoll X, García-Altés A, Pasarín MI, Piñeiro M, Villalbí JR. Veinticinco años de informes de salud en Barcelona: una apuesta por la transparencia y un instrumento para la acción. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2011;85(5):449–458. doi: 10.1590/S1135-57272011000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borrell C, Plasència A, Pañella H. Excés de Mortalltat en Una Área Urbana Cèntrica: El Cas de Ciutat Vella a Barcelona. Gac Sanit. 1991;5(27):243–253. doi: 10.1016/S0213-9111(91)71076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso J, Antó J. Desigualdades de Salud en Barcelona. Gac Sanit. 1988;2:4–12. doi: 10.1016/S0213-9111(88)70896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arias A, Rebagliato M, Palumbo MA, et al. Health inequalities in Barcelona and Valencia. Med Clin (Barc) 1993;100(8):281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borrell C, Arias A. Desigualtats de mortalitat en els barris de barcelona, 1983–89. Gac Sanit. 1993;7(38):205–220. doi: 10.1016/S0213-9111(93)71153-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borrell C, Arias A. Socioeconomic factors and mortality in urban settings: the case of Barcelona, Spain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49(5):460–465. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.5.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nebot M, Borrell C, Villalbí JR. Adolescent motherhood and socioeconomic factors. Eur J Pub Health. 1997;7(2):144–148. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/7.2.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasarín MI, Borrell C, Plasència A. ¿Dos patrones de desigualdades sociales en mortalidad en Barcelona? Gac Sanit. 1999;13(6):431–440. doi: 10.1016/S0213-9111(99)71403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brugal MT, Domingo-Salvany A, Maguire A, Caylà JA, Villalbí JR, Hartnoll R. A small area analysis estimating the prevalence of addiction to opioids in Barcelona, 1993. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(8):488–494. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.8.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brugal MT, Borrell C, Díaz-Quijano E, Pasarín MI, García-Olalla P, Villalbí JR. Deprivation and AIDS in a southern European city: different patterns across transmission group. Eur J Pub Health. 2003;13(3):259–261. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasarin MI, Borrell C, Brugal MT, Díaz-Quijano E. Weighing social and economic determinants related to inequalities in mortality. J Urban Heal Bull New York Acad Med. 2004;81(3):349–362. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marí-Dell’Olmo M, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Garcia-Olalla P, et al. Individual and community-level effects in the socioeconomic inequalities of AIDS-related mortality in an urban area of southern Europe. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(3):232–240. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.048017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Subirats I, Pérez G, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Muñoz DR, Salvador J, Salvador J. Neighborhood inequalities in adverse pregnancy outcomes in an urban setting in Spain: a multilevel approach. J Urban Health. 2012;89(3):447–463. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9648-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotsens M, Marí-Dell’Olmo M, Pérez K, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in injury mortality in small areas of 15 European cities. Health Place. 2013;24:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borrell C, Mari-Dell’olmo M, Palencia L, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality in 16 European cities. Scand J Public Health. 2014;42(3):245–254. doi: 10.1177/1403494814522556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marí-Dell’olmo M, Gotsens M, Borrell C, et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in ischemic heart disease mortality in small areas of nine Spanish cities from 1996 to 2007 using smoothed ANOVA. J Urban Health. 2014;91(1):46–61. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9799-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marí-Dell’Olmo M, Gotsens M, Palència L, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific mortality in 15 European cities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(5):432–441. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borrell C, Villalbí J, Díez E, Brugal M, Benach J. Municipal policies. The example of Barcelona. In: e, Bakker M, eds. Reducing inequalities in health: a European perspective. Ed. Outledge; 2002.

- 30.Díez E, Villalbí JR, Benaque A, Nebot M. Inequalities in maternal-child health: impact of an intervention. Gac Sanit. 1995;9(49):224–231. doi: 10.1016/S0213-9111(95)71241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Díez E, Clavería J, Serra T, et al. Evaluation of a social health intervention among homeless tuberculosis patients. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996;77(5):420–424. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8479(96)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ospina JE, Orcau À, Millet J-P, Sánchez F, Casals M, Caylà JA. Community health workers improve contact tracing among immigrants with tuberculosis in Barcelona. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manzanera R, Torralba L, Brugal M, Armengol R, Solanes P, Villalbí JR. Coping with the toll of heroin: 10 years of the Barcelona Action Plan on Drugs, Spain. Gac Sanit. 2000;14(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/S0213-9111(00)71429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villalbí JR, Guarga A, Pasarín MI, Gil M, Borrell C. Correction of social inequalities in health: reform of primary health care as a strategy. Aten Primaria. 1998;21(1):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehdipanah R, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Malmusi D, et al. The effects of an urban renewal project on health and health inequalities: a quasi-experimental study in Barcelona. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(9):811–817. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuertes C, Pasarín MI, Borrell C, Artazcoz L, Díez E, Group of Health in the Neighbourhoods Feasibility of a community action model oriented to reduce inequalities in health. Health Policy. 2012;107(2–3):289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ajuntament de Barcelona . Mesura de Govern d’Acció Conjunta per La Reducció de Les Desigualtats Socials En Salut. Ajuntament de Barcelona: Barcelona; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanlon J, Pickett G. Public health administration and practice. 8. St. Louis: Mirror/Moshy College Publishing; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona. La Salut a Barcelona 2014. Barcelona: Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona; 2015.

- 40.Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona. Barcelona Salut Als Barris. Programa d’intervencions comunitàries per reduir les desigualtats en Salut. memòria d’Activitat 2016. Barcelona: Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona; 2017.

- 41.Borrell C, Pons-Vigués M, Morrison J, Díez È. Factors and processes influencing health inequalities in urban areas. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(5):389–391. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-202014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrison J, Pons-Vigués M, Bécares L, et al. Health inequalities in European cities: perceptions and beliefs among local policymakers. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004454. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison J, Pons-Vigués M, Díez E, Pasarin MI, Salas-Nicás S, Borrell C. Perceptions and beliefs of public policymakers in a southern European city. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0143-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan American Health Organization. Road Map for the Plan of Action on Health in All Policies. Washington DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2016.

- 45.Institute for State and Local Governance. Equality indicators. http://equalityindicators.org/ (2015). Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

- 46.Besag J, York J, Mollié A. Bayesian image restoration, with two applications in spatial statistics. Ann Inst Stat Math. 1991;43(1):1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00116466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martí-Pastor M, García de Olalla P, Barberá M-J, et al. Epidemiology of infections by HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea and lymphogranuloma venereum in Barcelona City: a population-based incidence study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1015. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2344-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization. Handbook on health inequality monitoring: with a special focus on low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- 49.Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Schlotheuber A, Victora C, Boerma T, Barros AJD. Data resource profile: WHO Health Equity Monitor (HEM) Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(5):1404–1405e. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health inequalities interactive tool. 1996–2016. https://www.cihi.ca/en/factors-influencing-health/socio-economic/health-inequalities-interactive-tool. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

- 51.Public Health England. Health profiles. http://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/health-profiles. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

- 52.Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona. InfoBarris BCN. www.aspb.cat/infobarris. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.

- 53.Communities Count. Social and health indicators across King County. 2012. http://www.communitiescount.org/. Accessed 9 Nov 2016.