Abstract

The Urban Health Equity Assessment Response Tool (Urban HEART) combines statistical evidence and community knowledge to address urban health inequities. This paper describes the process of adopting and implementing this tool for Detroit, Michigan, the first city in the USA to use it. The six steps of Urban HEART were implemented by the Healthy Environments Partnership, a community-based participatory research partnership made up of community-based organizations, health service providers, and researchers based in academic institutions. Local indicators and benchmarks were identified and criteria established to prioritize a response plan. We examine how principles of CBPR influenced this process, including the development of a collaborative and equitable process that offered learning opportunities and capacity building among all partners. For the health equity matrix, 15 indicators were chosen within the Urban HEART five policy domains: physical environment and infrastructure, social and human development, economics, governance, and population health. Partners defined the criteria and ranked them for use in assessing and prioritizing health equity gaps. Subsequently, partners generated a series of potential actions for indicators prioritized in this process. Engagement of community partners contributed to benchmark selection and modification, and provided opportunities for dialog and co-learning throughout the process. Application of a CBPR approach provided a foundation for engagement of partners in the Urban HEART process of identifying health equity gaps. This approach offered multiple opportunities for discussion that shaped interpretation and development of strategies to address identified issues to achieve health equity.

Keywords: Urban health, Health equity, Social determinants of health, Health equity assessment, Detroit

Introduction

In the early 1900s, Detroit ranked among the nation’s largest metropolises with a prosperous motor industry [1]. However, through a combination of events including the closing of industrial factories in the city and racial injustices in housing access and affordability, Detroit experienced depopulation, increased unemployment, and disinvestment starting in the 1960s [2, 3]. Health inequities in Detroit continue to reflect on these historical events and are further perpetuated by physical and social factors such as lack of access to employment and stable housing, healthy foods, health care, and clean environments; all determinants linked to negative health outcomes like asthma, cardiovascular disease, and psychological distress [2, 4–7]. Changes needed to address these issues include, for example, improvements in urban infrastructures, access to jobs, safe places to recreate, and an end to violence, racism, and segregation. Researchers, community-based organizations, and government groups have implemented various strategies and programs to address some of these issues [8, 9]. However, a tool that combines statistical evidence and community knowledge to evaluate and address urban health equity in and across Detroit’s neighborhoods can play an essential role in ongoing efforts to promote health equity in the city and its surrounding areas.

This paper describes the process of adopting and implementing such a tool, the Urban Health Equity Assessment Response Tool (Urban HEART), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), in Detroit, Michigan, the first city in the USA to use it. This is the first paper of its kind to focus on the use of a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to combine the Urban HEART tool with community knowledge, in order to promote health equity in Detroit.

Background

Urban HEART

In response to the Commission on Social Determinants of Health Report [10], the WHO developed the Urban HEART [10]. This tool was designed to provide the required evidence for governments, community-based organizations, and researchers to make more informed decisions to ensure equitable development toward the end of achieving health equity [10]. Urban HEART focuses on five policy domains: physical environment and infrastructure, social and human development, economics, governance, and population health. As part of the implementation, teams identify local indicators within each domain to measure existing disparities among populations in urban environments, recognize gaps and relationships among findings, and establish a foundation for planning to reduce or eliminate inequities [10]. For example, within the economics domain, indicators like household income, employment, or capital wealth can be selected [10].

Urban HEART has been used in over 100 cities worldwide to inform policy change, guide community efforts, and improve existing data. Prasad and colleagues (2015) evaluated the implementation of Urban HEART in 15 Asian and African cities from 2008 to 2010 [11]. Evaluation results indicated that most cities reported that Urban HEART was easy to use and offered important opportunities to incorporate multiple sectors and that the findings were used to support interventions and policy changes. Urban HEART relies primarily on identification of existing data, and some cities expressed difficulties in finding relevant data and in locating high-quality data. Furthermore, financial and political constraints were noted as barriers in implementing the tool [11].

Despite these challenges, Urban HEART offers a mechanism for identifying measurable indicators for health equity. Its purpose is to highlight areas of concern and needing attention across a city rather than to rank neighborhoods by order. The information gathered through this process serves as a resource for discussion and generation of potential actions that address areas of concern identified through the analysis [10]. In this paper, we describe the adaptation and implementation of Urban HEART Detroit, the first US city in which it has been used. Furthermore, while other Urban HEART cities have mentioned the importance of working in inclusive teams with various stakeholders, this is the first paper of its kind to detail the specific process of incorporating multiple constituents in the Urban HEART tool through a CBPR process.

Methods

The Urban HEART tool involves six steps: (1) building an inclusive team; (2) defining local indicators and benchmarks indicative of social determinants of health equity; (3) assembling relevant and valid data with which to assess those indicators; (4) generating evidence; (5) assessing and prioritizing health equity gaps and gradients; and (6) identifying the best response to health equity issues identified in the previous steps. The evidence generated is in the form of a matrix that allows assessment of indicators at the relevant geographic units, using the data collected. The application of the tool is provided in a user-friendly manual that expands on each of these steps by providing guidance and tips on implementation [10].

While Urban HEART encourages a collaborative process, the Detroit team implemented the tool using a CBPR approach that emphasizes equity within a partnership that supports engagement of all partners to contribute their expertise and share in the decision-making process [9, 12]. Table 1 presents nine guiding principles for the CBPR identified and are described in greater detail by Israel and colleagues [13] (column 1), with the corresponding six steps of the Urban HEART process shown in column 2.

Table 1.

CBPR principles and corresponding Urban HEART steps

| Community-based participatory research principles [8] (1) |

Urban HEART steps [5] (2) |

|---|---|

| 1. CBPR acknowledges community as a unit of identity. | Step 1: Build an inclusive team |

| 2. CBPR builds on strengths and resources within the community. | |

| 3. CBPR facilitates a collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of research, involving an empowering and power-sharing process that attends to social inequalities. | Step 2: Defining local indicators and benchmarks |

| 4. CBPR fosters co-learning and capacity building among all partners. | Step 3: Assembling data and generating evidence |

| 5. CBPR integrates and achieves a balance between knowledge generation and intervention for the mutual benefit of all partners. | Step 4: Generating evidence |

| 6. CBPR focuses on the local relevance of public health problems and on ecological perspectives that attend to the multiple determinants of health. | Step 5: Prioritizing health equity gaps and gradients |

| 7. CBPR involves systems development using a cyclical and iterative process. | Step 6: Developing a response plan |

| 8. CBPR disseminates results to all partners and involves them in the wider dissemination of results. | |

| 9. CBPR involves a long-term process and commitment to sustainability. | Future steps |

Urban HEART Detroit was adapted and implemented from November 2015 to August 2016, by the Healthy Environments Partnership (HEP), a long-standing CBPR partnership that focuses on social determinants of health equity in Detroit (see description under Step 1 “Step 1: Building an Inclusive Team”). Drawing on notes from monthly meetings of the governing Steering Committee, and products developed throughout the implementation of the tool, in the following section, we describe the approach taken in each of the Urban HEART steps while explaining how the CBPR principles were integrated.

Results: Urban Heart DETROIT Process

For each step of implementing the Urban HEART tool, we discuss the process through which it was implemented and consider the challenges, tensions, and/or contributions that arose through that process.

Step 1: Building an Inclusive Team

Urban HEART depends on building a team around [10] health equity within a city. The Urban HEART manual recommends the inclusion of intersectoral stakeholders, intergovernmental representatives, and community members who can dedicate time to complete each of the steps proposed [10]. In the case of Urban HEART Detroit, it was critical to engage Detroit-based individuals and groups who were equipped to provide insight on issues within the city.

Central to a CBPR approach is a focus on the community as a unit of identity (CBPR principle P1) (Table 1) as well as a focus on strengths and resources within the community (CBPR P2) [10]. One resource in Detroit is the long-standing HEP, a CBPR partnership made up of community-based organizations, health service providers, and researchers based in academic institutions (www.hepdetroit.org), which has been working toward solutions for achieving health equity in Detroit. HEP includes the Chandler Park Conservancy, Detroit Health Department, Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, Eastside Community Network, Friends of Parkside, Henry Ford Health System, University of Michigan School of Public Health, and community members-at-large. This group has been working together since 2000 to understand and address environmental contributors to health inequities in Detroit, using CBPR principles that emphasize inclusiveness and equity [5, 6].

The HEP Steering Committee (SC), made up of representatives from each of the organizations listed above, offered an existing and well-functioning team with which to implement the Urban HEART process (CBPR P3). The topic of Urban HEART was introduced to the team at one of its regular monthly meetings to explore the group’s potential interest in working through this process for the city of Detroit. Given its history of examining and addressing social determinants of health in Detroit, following discussion of its synergies with ongoing work, the SC agreed to dedicate a portion of its 2-h monthly meetings for work on Urban HEART. Each of the steps described subsequently was completed with the guidance and active engagement of the SC. Conversations were structured following the steps of Urban HEART, and members of the academic research team worked between these meetings to create visual tools and processes to facilitate active and equitable engagement of all partners (as described subsequently) to allow for a collaborative and co-learning process (CBPR P4). In addition to discussions at monthly SC meetings, three additional meetings were held with the Detroit Health Department staff and leadership to discuss the process and the potential for integration with long-range plans for the institution to incorporate data monitoring and community involvement into their efforts.

Step 2: Defining Local Indicators and Benchmarks

Urban HEART promotes a collaborative partnership in each of its steps. In accordance with CBPR principles, to facilitate such a collaboration with an emphasis on power-sharing and fostering co-learning and capacity building among partners, Step 2 was divided into the following phases that were completed over three meetings with the SC.

Indicators

To develop a list of indicators and benchmarks indicative of social determinants of health in Detroit, the selection of indicators was completed in two phases. In the first phase, the academic researchers used the Urban HEART-recommended list [10] as guidance and searched existing databases for all possible indicators within the five domains, including dates and geographic scale. These findings were used to generate a list as a starting point for the second phase which consisted of a discussion with the SC to select a working list of indicators to include in the assessment. This would allow the addition or elimination of indicators in later phases based on emerging needs. It would also provide the opportunity to continue identifying potential indicators without the limitation of time.

In the initial SC discussions of the indicator list, members commented on the framing of most indicators, raising a concern that these indicators reflected a deficit approach to consideration of communities (e.g., unemployment, less than high school education, living in poverty). Members of the SC pointed to a history in which Detroit has been portrayed negatively in various media [14] and noted that a principle of CBPR is a focus on strengths and resources that exist within communities (CBPR P2). They voiced concerns that a focus on deficits might exacerbate this portrayal. Research has demonstrated the association of resources within communities with long-term health outcomes [15] supporting their potential inclusion in conversations about social determinants of health in urban settings. A recommendation was made by the SC to incorporate indicators that reflect strengths or assets within communities wherever applicable, including the potential for identifying community resources that reflect capacities and strengths within communities.

In response to this recommendation, the final list of indicators reflected more asset-based community indicators, while retaining some in their original form. For example, within the social and human development domain, rather than focusing on the percent with less than high school education (reflecting a potentially vulnerable population), indicators were included reflecting percent with more than a high school education. Within that same domain, percentage of households living below the poverty line was changed with percentage of children living above poverty. In the physical environment and infrastructure domains, green space (parkland area) and non-motorized transportation (non-auto commuters) were added; and for the governance domain, voter turnout. In addition to reflecting the values of the participants in this process, these revisions to the original Urban HEART framework help to identify community resources that may be useful in considering opportunities for addressing health inequities.

Benchmarks

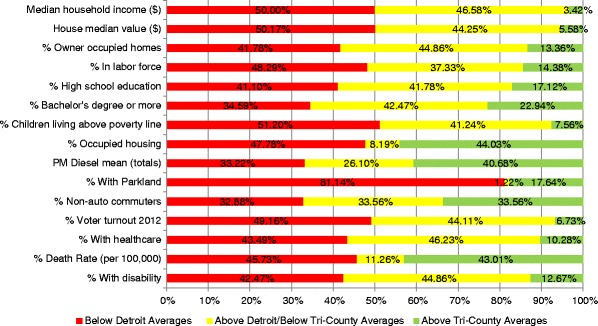

In addition, Step 2 involves identification of relevant benchmarks or areas for improvement within each indicator. Urban HEART Detroit considered both national and local benchmarks as potential indicators, and in this process generated and discussed preliminary data using each of these benchmarks. After some discussion and consideration of different potential benchmarks, the SC decided to use the city of Detroit and the Detroit tri-county area, encompassing Wayne (the county in which Detroit is located), Oakland, and Macomb Counties (the latter two are immediately adjacent counties) as initial benchmarks, leaving open the possibility of shifting to national benchmarks later as relevant. To implement the benchmarking step, each of the 297 census block groups were color coded for each of the 15 indicators using the following metric: indicator level falls below the average level for Detroit city (red); indicator level falls above the average level for Detroit City but below the level for the tri-county area (yellow); and indicator level falls above the tri-county average (green).

Steps 3 and 4: Assembling Data and Generating Evidence

As part of the data collection for each of the indicators, and in keeping with recommendations provided in the Urban HEART Manual [10], publicly available data was identified for each of the indicators, to assure the accessibility of the tool and to facilitate access to data for ongoing monitoring. Most data came from the American Community Survey (ACS), a yearly survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, which is representative of the population [16]. The National Air Toxics Assessment from 2011 was used to attain broad estimates of diesel PM exposures [17]. Average percent of population that died per year from 2009 to 2013 was obtained from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS), using 5-year estimates (2009–2013), the most recent data available [18].

Although it is recommended to include information on infectious diseases like tuberculosis and non-communicable diseases like diabetes, this information was not available at the desired census tract (CT) level at the time the Urban HEART was undertaken. Instead, we used all-cause mortality from MDHHS and disability rates (percentage of individuals aged 18–64 with a physical disability) from the ACS to assess differential distribution of health risks across CTs. Both indicators have been used in similar capacities in previous literature and on the recommended list for Urban HEART by the WHO [10, 19, 20].

Cities implementing Urban HEART have used a variety of geographic scales in creating their matrices, including neighborhood level in Toronto, districts in Tehran, and Medical Office of Health areas in Colombo [10, 21, 22]. Potential scales within Detroit include its 105 designated neighborhoods, 33 zip codes, and 7 City Council districts or CTs or block groups (U.S. Census Bureau 2015). By providing this information and having a discussion as a group, it was agreed to complete the matrix at the CT level, given that most data were available at this finer resolution, and it offered the opportunity to more clearly represent variability across geographic areas. The matrix and analyses completed for Urban HEART Detroit were completed using the 297 CTs within the city of Detroit.

After assembling the data, as described above, the next step was to generate evidence to identify health equity challenges and opportunities. As described in the Urban HEART users’ manual, the purpose of this step is to enable “stakeholders to see evidence of health inequities in cities and use evidence to plan a response.” [10] Using the benchmarking process described in the previous step, a full matrix color coded for each indicator at each census block group was generated. Due to the volume of data represented in the matrix (4455 data points, 15 variables across 297 CTs), and following the guidelines from Urban HEART, the team developed summary graphs and legends to present the material in more readily accessible formats. Urban HEART offers two potential methods for viewing the data: summarized as indicators or summarized as geographical areas. Following discussion, the SC expressed interest in focusing on indicators, both to avoid potentially stigmatizing areas of the city identified as having more “red” indicators (see Step 2) and by offering an opportunity to identify indicators that posed more widespread challenges and opportunities within the city.

Figure 1 shows the percent distribution for Urban HEART indicators for Detroit, using the color-coded benchmarks described above. Based on the SC’s preference for focusing on indicators, this visual offers a summary of how the city is performing in those areas. Multiple versions of the figure were created to enable the SC to view multiple potential perspectives. The figure shown here was settled upon as the most user-friendly and thus primarily used for subsequent steps as the evidence needed to guide both the prioritization and response steps.

Fig. 1.

The percent distribution of CTs for each of the indicators

Here again, discussions among the SC were critical in enabling Urban HEART Detroit to move forward with a strong understanding of the historical, economic, sociopolitical, and geographic context of the city (CBPR P6). As one example, SC members raised questions regarding the interpretation of home ownership as a positive factor, pointing to the economic recession and the mortgage crisis of the early 2010s, which hit Detroit particularly hard [23]. Consequently, home ownership may have become a burden for some, especially low-income families, with general distrust in financial institutions leading to the abandonment of the home ownership ideal among some residents. Although the indicator was included in the final matrix, the SC discussions provided important insight on the Detroit context when interpreting the results and discussing health equity gaps in the city.

Step 5: Prioritizing Health Equity Gaps and Gradients

The goal of Step 5 was to prioritize the identified equity gaps within the city that required action [10]. This step is synergistic with CBPR principle 5, establishing a balance between knowledge generation and action to address public health challenges through the development of solutions and recommendations to benefit the public’s health. To establish a clear, equitable, and mutually agreed upon process for prioritizing the health equity gaps indicated in the data, SC members discussed information that would be helpful or necessary for prioritizing indicators and actions. Suggestions were written on newsprint and displayed for the group to allow members to build on previous comments throughout the discussion. Once the list was generated, SC members were each given four sticky dots and invited to place them next to the newsprint suggestions to identify those that they felt were the most important criteria to be used in the prioritization process. Table 2 presents the list of the top ten ideas generated and the total “votes” each received.

Table 2.

Top ten criteria listed in order of most number of votes

| Votes | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 7 | Seriousness of problem or issue |

| 6 | Timing and opportunity |

| 6 | Fill void or gap and added value |

| 5 | Length of time to resolve |

| 4 | Magnitude of problem and number of people affected |

| 4 | Fundable |

| 3 | Likelihood of success |

| 2 | Feasibility of doing something about issue |

| 2 | Ability to form common agenda to address issue |

| 2 | Ripple effect—if effect one thing, others will follow |

| 2 | Impact on vulnerable population (e.g. children) |

This step and the criteria identified helped the group develop a framework for creating and prioritizing potential solutions to the issues reflected in the matrix as a starting point for establishing an action-based response plan (CBPR P5). To help strengthen the capacity of the team and to promote co-learning (CBPR P4), the research support team also shared with the SC some examples of how Urban HEART had been used in other cities and various other community needs assessments to assist the SC in thinking about potential strategies for prioritizing issues and developing potential solutions [10, 11].

Step 6: Developing a Response Plan

The final step in the Urban HEART process is the development of a response plan on recommendations for governments and community to address the priority health equity gaps identified [10]. From September 2016 to February 2017, Urban HEART Detroit has moved this process forward by generating ideas about specific strategies that might be used to address the health equity gaps identified for each indicator. This process was supported in part by development of a brief background of response plans and related actions undertaken by other cities that have used the Urban HEART tool, to provide examples of the types of responses that might be proposed. Each indicator (e.g., high school education attainment, employment status) was written on a piece of newsprint and posted on the wall. SC members were invited to brainstorm potential solutions or responses to the various indicators (Table 3). Each participant wrote their ideas on a sticky note and placed each on the corresponding newsprint. At the end of the exercise, group members circulated around the room to review each other’s ideas and to discuss the ideas generated. To focus on the local relevance of the proposed solutions, discussions included consideration of groups or organizations within the city, including municipal institutions, which might be interested in taking action on the issue or are already engaged in addressing the issue.

Table 3.

Proposed solutions for three Urban HEART indicators

| Indicator | Proposed solutions |

|---|---|

| Percent children not living in poverty | • Provide subsidized housing to assure parents with low income can use their money on other things to support their children. • Provide minimum income to households with young children to assure basic needs are met. • Improve parents’ access to job training to improve employment prospects. |

| Percent high school education | • Increase housing stability so kids are not homeless or changing schools all the time. • Provide platform/opportunity to engage students on the fringes of dropping out. • Invest in schools so kids get a high-quality education. • Provide hands-on learning, vocational training, and job training while in school. • Provide college classes/credit opportunities for high school students to get into college. • Incentivize high school completion (e.g., offer tuition support for college). |

| Percent in labor force | • Provide companies better incentives to move to Detroit. • Create policies that ensure that a proportion of all new jobs created in the city should go to local residents. • Provide workforce development training in the community. • Provide support services to enable people to work (e.g., transportation, childcare). |

Proposed solutions reflected ecological perspectives that ranged from community, policy, and physical and social structural change. Table 3 provides examples of proposed solutions for the indicators percent children not living in poverty, percent high school education, and percent in labor force.

Future Steps

The implementation of the Urban HEART tool, although presented as a linear process, and its adaptation and implementation in Detroit were iterative (CBPR P7), reflecting the flexibility needed to respond to the points raised by the SC throughout the different steps. For example, the lack of data available for health at the CT level at the start of the project resulted in a parallel process of finding sources for additional data. Furthermore, while discussing prioritization of health equity gaps (Step 5), the SC suggested including the percent of bachelor degree attainment in addition to the high school education indicator, as a further indicator of community assets as well as challenges and to focus attention on potential solutions to address education gaps in the city.

The results and findings from Urban HEART Detroit have resulted in a series of next steps that include moving forward on emerging research areas and seeking funding to support those actions. Furthermore, the process has resulted in several meetings with the Detroit Health Department to identify synergies while contributing to the forthcoming Social Determinants of Health Strategic Plan for the city. All partners have been involved in the dissemination of this work, through peer-reviewed publications and presentations for different organizations and groups (CBPR P8), and there is a commitment to long-standing engagement of all partners as the process moves forward (CBPR P9). We believe this is an ongoing long-term process which will contribute to the continuing efforts within the city to promote health equity, through identification of relevant data and benchmarks to assess progress.

Discussion

A strong community-academic partnership approach to implementation of the Urban HEART process in Detroit has provided the opportunity to incorporate contextual knowledge and community challenges, resources, and assets and to begin identifying potential feasible and appropriate responses. As the first city in the USA to use Urban HEART, this creates a unique and important opportunity to share our experiences creating a platform for equitable engagement of multiple local groups in this process that may serve as a guide for future cities that are seeking to implement the tool. While other Urban HEART cities have mentioned the importance of working in inclusive teams with various stakeholders, this is the first paper of its kind to detail the specific process of incorporating multiple constituents through a CBPR process.

The Urban HEART tool provides the opportunity to start or continue discussions of upstream solutions to health-related factors affecting a city. The Urban HEART manual provides tips and guidelines on how to facilitate these conversations [10], and in recent years, there have been guiding reports on how to discuss social determinants of health and health equity [24, 25]. However, there has been limited information available regarding the process through which Urban HEART has been implemented with particular attention to the equitable engagement of residents, community-based organizations, governments, and academic institutions as an important mechanism to addressing health equity. In these analyses, we offer an examination of one such process, using a CBPR, which attempted to ensure equitable engagement of multiple constituents in identification of social, economic, and physical environmental determinants of health and their connections to health inequities within a city.

A strength of Urban HEART Detroit was the opportunity to work with the SC, an existing and well-functioning partnership of actively engaged representatives from community-based organizations, health service providers, and academic institutions who have been working together to address health equity in Detroit since 2000. Partners provided a variety of perspectives when planning and discussing the project. While we recognize such qualifications may not always exist, an emphasis on identifying and working with existing assets and resources within the community, and on strengthening partnerships with others in the community, is central to strengthening capacity [13] that will be essential to effective implementation of solutions to health equity concerns within urban contexts.

The expertise of community organizations and residents and their deep knowledge of the history and social and political context of Detroit provided substantial depth as the Urban HEART conversations unfolded. Co-learning opportunities included differing perspectives on the use of home ownership as an indicator of economic status and its links to better health and well-being [26]. These insights from members of the SC are critical, given recent research on the stability housing ownership provides [23] and associations with childhood well-being [27], and resonate with findings suggesting that in recent years, home ownership has become a burden for low-income families, resulting in economic strain and foreclosure [28] linked to negative health outcomes including poor mental health status [23]. This was also reflected in the final step that generated considerable discussion among the SC centered on interventions related to financial institutions including fair lending opportunities and incentives for purchasing homes.

The process described above supports the importance of building on existing community capacity and efforts. A limitation of the Urban HEART tool is the lack of accountability measures related to the process, resulting in a heavy reliance on the team leading the process to ensure that a collaborative and equitable partnership is implemented throughout all phases of Urban HEART. Incorporation of more explicit processes, such as CBPR principles, can provide a guide for others who wish to assure equitable engagement of a wide range of constituents in the process, as well as offering a mechanism for assuring accountability to the process, as described above. Furthermore, incorporation of a partnership evaluation process, to assess the extent to which CBPR principles are being followed, also would address accountability issues [29, 30].

In addition, the process presented here suggests the potential for future Urban HEART teams to discuss and identify other asset-based indicators including community networks and programs. Identifying both problems and assets provides a better understanding of the complexities associated with health inequities within a city and how to begin addressing them [31]. By strengthening a focus on community assets and resources within the context of conversations about strategies for addressing health inequities, solutions that specifically strengthen these assets and resources within communities could also serve as strategies for improving health.

Urban HEART Detroit is an ongoing effort and is unfolding in conjunction with the SC. The team has identified areas for research and action and is working to secure funding to move forward several ideas generated. The analysis conducted through Urban HEART has provided pilot data and a foundation for developing proposals for larger grant funding to continue this work and act on priorities identified in this process. While this was a natural next step for this long-standing partnership that continues to address health inequities in Detroit, Urban HEART can be a facilitator in establishing partnerships similarly dedicated to a long-term process of addressing social determinants of health in other urban settings. Furthermore, the monitoring tool that is part of Urban HEART [10] can be incorporated and used in Detroit in the coming years to continue framing health equity conversations to increase momentum on the gains achieved.

Conclusion

In this article, we have described the adaptation and implementation of Urban HEART Detroit, including the active engagement of an established group of community organizations, residents, academic researchers, and health service providers with a long history of working together to address social determinants of health. Above, we have detailed specific contributions made by community partners throughout the implementation of Urban HEART within the Detroit context. These contributions reflect, and were informed by the CBPR principles that this group uses to guide their efforts, and made substantial unique contributions to Urban HEART Detroit. In addition to shaping and, we believe, strengthening the dialog that unfolded regarding social determinants of health in Detroit, these contributions have implications for others who may wish to implement the tool in other settings. Specifically, they point to the contributions that can be made by creating a space for equitable engagement of a broad range of locally based groups and residents, facilitating contributions informed by a deep understanding of local political, economic, and social histories, as well as existing networks and relationships that can facilitate multi-directional communication on these topics. CBPR principles offer one strategy to further strengthen the effectiveness of the Urban HEART tool by actively engaging broad perspectives from multiple constituencies in dialog toward the end of achieving health equity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the HEP Steering Committee: Chandler Park Conservancy, Detroit Health Department, Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, Eastside Community Network, Friends of Parkside, Henry Ford Health System, Institute for Population Health, University of Michigan School of Public Health, and community members-at-large, for their contributions to the work described here.

Funding

Funding for the study was provided by the World Health Organization Kobe Center in Japan, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24MD001619), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01 ES022616 and P30ES017885), and Fred A. and Barbara M. Erb Family Foundation.

References

- 1.Sugrue TJ. The origins of the urban crisis: race and inequality in postwar Detroit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2014.

- 2.Schulz AJ, Mentz GB, Sampson N, et al. Race and the distribution of social and physical environmental risk. Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2016;13(2):285–304. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X16000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farley R. The bankruptcy of Detroit: what role did race play?: the bankruptcy of Detroit. City Community. 2015;14(2):118–137. doi: 10.1111/cico.12106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsen L, Sherman LS, Cole LB, Karwat D, Badiane K, Coseo P. Social justice and sustainability in poor neighborhoods learning and living in Southwest Detroit. J Plan Educ Res. 2014;34(1):5–18. doi: 10.1177/0739456X13516498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(4):660–667. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz AJ, Kannan S, Dvonch JT, et al. Social and physical environments and disparities in risk for cardiovascular disease: the healthy environments partnership conceptual model. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(12):1817–1825. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz AJ, Williams D, Israel BA, et al. Unfair treatment, neighborhood effects, and mental health in the Detroit metropolitan area. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(3):314. doi: 10.2307/2676323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle urban research centers. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Urban HEART Manual. http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/publications/urban_heart_manual.pdf?ua=1. Published 2010. Accessed 18 Dec 2016.

- 11.Prasad A, Kano M, Dagg KA-M, et al. Prioritizing action on health inequities in cities: an evaluation of Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool (Urban HEART) in 15 cities from Asia and Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Chapter 1: introduction to methods for cbpr for health. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research For Health. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2013. p. 3–38.

- 14.Abbey-Lambertz K. 11 stereotypes Detroiters are tired of hearing | The Huffington Post. The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/05/detroit-stereoptypes-misconceptions-blank-slate_n_6800606.html. Published March 5, 2015. Accessed 18 Dec 2016.

- 15.Sahn DE, Stifel D. Exploring alternative measures of welfare in the absence of expenditure data. Rev Income Wealth. 2003;49(4):463–489. doi: 10.1111/j.0034-6586.2003.00100.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bureau UC. American Community Survey (ACS). https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed 22 Dec 2016.

- 17.US EPA O. 2011 NATA: assessment results. https://www.epa.gov/national-air-toxics-assessment/2011-nata-assessment-results. Accessed 22 Dec 2016.

- 18.Veinot TC, Okullo D. Data Driven Detroit. Neighborhood effects: health outcomes dataset. Ann Arbor, MI: Deep Blue Data; 2016.

- 19.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski J, Williams DR, Mero R, Chen J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9624022?dopt=Abstract. Published 1998. Accessed 19 Dec 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asadi-Lari M, Vaez-Mahdavi M, Faghihzadeh S, et al. The application of urban health equity assessment and response tool (Urban HEART) in Tehran; concepts and frameworks. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2010;24(3):175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centre for Research in Inner City Health. Urban HEART @ Toronto: Technical report/user guide. Centre for Research in Inner City Health. 2014. http://www.torontohealthprofiles.ca/urbanheartattoronto/UrbanHeart_TechnicalReport_v1.pdf. Accessed 22 Dec 2016.

- 23.Burgard SA, Seefeldt KS, Zelner S. Housing instability and health: findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2215–2224. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2020: social determinants of health. 2014. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed on December 8, 2016.

- 25.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. A new way to talk about the social determinants of health. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/rwjf63023. Published 2010. Accessed 22 Dec 2016.

- 26.Rohe WM, Zandt SV, McCarthy G. Home ownership and access to opportunity. Hous Stud. 2002;17(1):51–61. doi: 10.1080/02673030120105884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziol-Guest KM, McKenna CC. Early childhood housing instability and school readiness. Child Dev. 2014;85(1):103–113. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannuscio CC, Alley DE, Pagán JA, et al. Housing strain, mortgage foreclosure, and health. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(3):134–142.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Israel BA, Lantz PM, McGranaghan RJ, Guzman RJ, Lichtenstein R, Rowe Z. Chapter 13: documentation and evaluation of CBPR partnerships: the use of in-depth interviews and closed-ended questionnaires. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research For Health. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2013. p. 369–98.

- 30.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Lantz PM. Chapter 24: Assessing and strengthening characteristics of effective groups in community based participatory research partnerships. In: Garvin CD, Gutierrez LM, Galinsky MJ, editors. Handbook of Social Work with Groups. New York City: Guilford Press; 2017. p. 433–53.

- 31.Lasker RD. Broadening participation in community problem solving: a multidisciplinary model to support collaborative practice and research. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2003;80(1):14–60. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]