Abstract

Aim

Maxillofacial trauma when associated with concomitant injuries has a significant potential for increased morbidity. This study aims to identify the causes of trauma, evaluate the types of associated injuries and to highlight the significance of multi professional collaboration in sequencing of treatment.

Patients and Methods

A total of 300 patients who reported to the casualty of a tertiary Hospital in Karnataka with facial fractures were enrolled.

Results

Associated injuries were sustained by 162 patients. The predominant aetiology was the Road Traffic Accident with maximum number of patients in the age group of 20–29 and a male to female ratio of 10.1:1. The mandible was the most frequently fractured bone. Head injury was the most common associated injury. The mortality rate was 0.66%. The mean ISS and GCS values among the patients who sustained associated injuries along with maxillofacial trauma were higher and lower respectively, as compared to those without associated injuries with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Implementation of strict road safety measures in the rural and interior regions of South India, to prevent morbidity and mortality due to road traffic accidents is essential. Injuries to the facial skeleton must be approached with the knowledge of probable associated injuries that could have been incurred.

Keywords: Maxillofacial trauma, Associated injuries, South India

Introduction

Nowadays, facial injuries have become a quotidian situation in the emergency rooms as the face is highly vulnerable to trauma due to the fact that it is the most exposed region of our body. Injuries can be incurred in situations such as the road traffic accidents, fall from height, inter-personal violence, animal attacks and sports. Facial trauma many a times occur in association with injuries to other organ systems of the body, and in such cases, there is an increase in the morbidity levels, demanding immediate intervention and management. The proficiency, with which a definite assessment is made, is a major factor in the prognosis of the patient. Treatment of the maxillofacial injuries would be complex without a comprehensive perception of the damage incurred by the other systems in the body of the victim. This study, intends to evaluate the individuals with maxillofacial trauma, identify the cause(s) for the trauma and thereby, recommend means to eliminate the cause, determine the incidence of concomitant injuries to other organ systems among those individuals, and to assess the role of the attending maxillofacial surgeon in providing a definitive diagnosis so that unforeseen emergency situations can be avoided.

Patients and Methods

300 patients who were the victims of maxillofacial trauma were included in a prospective study conducted over a period of 2 years between September 2013 to August 2015 and were divided into two groups

Group A—Patients with maxillofacial trauma without associated injuries.

Group B—Patients with maxillofacial trauma and with associated injuries.

The study population comprised of the patients reporting to the emergency department of a Tertiary hospital in Karnataka. The age, gender, etiology of trauma and maxillofacial injuries of the patients were recorded using a standard Performa devised for the study. The maxillofacial fractures were classified based on the location as nasal fracture, maxillary fracture, mandibular fracture, frontal bone fracture, lower orbital rim fracture, zygomatic fracture which were diagnosed by a primary clinical examination supported by a CT scan report.

The patients were also assessed for any associated injury (AI) if any. Injuries to the Brain, spine, chest-wall, extremities, pelvis and abdomen were considered as associated injuries. All the associated injuries were categorized into three main headings. Injuries to the brain were classified under head injuries; injuries to the extremities, chest wall, spine and pelvis were included under the orthopedic injuries while the injuries to the abdomen were included under the abdominal injuries. Injuries to the brain were suspected clinically by Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and confirmed by the CT scan, which was also used to diagnose any spine injuries. A primary clinical examination of the chest for signs of injury was done and a chest X-ray was advised to every patient to diagnose injuries to the Chest-wall. Patients suspected of injuries to the extremities in the clinical examination were advised X-rays of the limbs which provided a definite diagnosis for the limb and pelvis injuries. USG abdomen was used to confirm the presence of abdominal injuries in patients suspected of injury to the abdomen. The Injury Severity Score was used to assess the level of morbidity in patients with poly-trauma.

Injury Severity Score(ISS)

The ISS is the sum of the squares of the highest Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS) in three of the six predetermined regions of the body. The maximum practical ISS is 75 (52 + 52 + 52) [1].

Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS)

Injuries are ranked on a scale of 1–6, with 1 being minor, 5 severe, and 6 a non-survivable injury [2].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for continu-ous variables. Inferential statistics included z-test to check the difference between the groups. P value less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

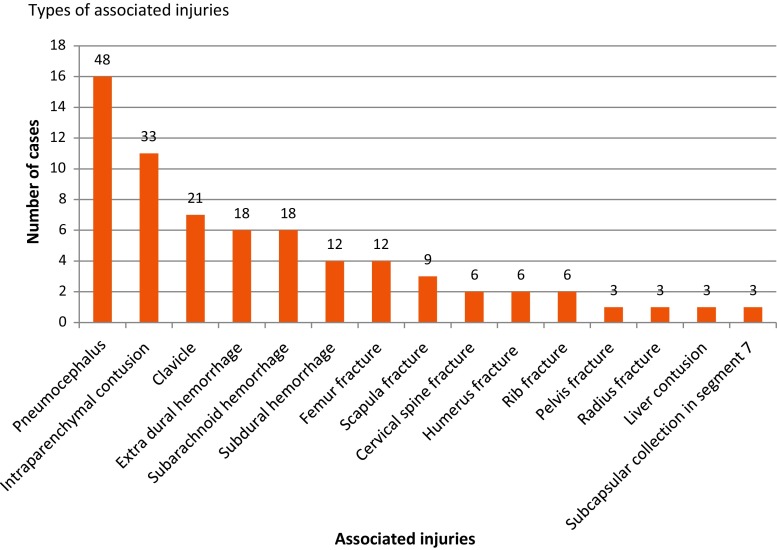

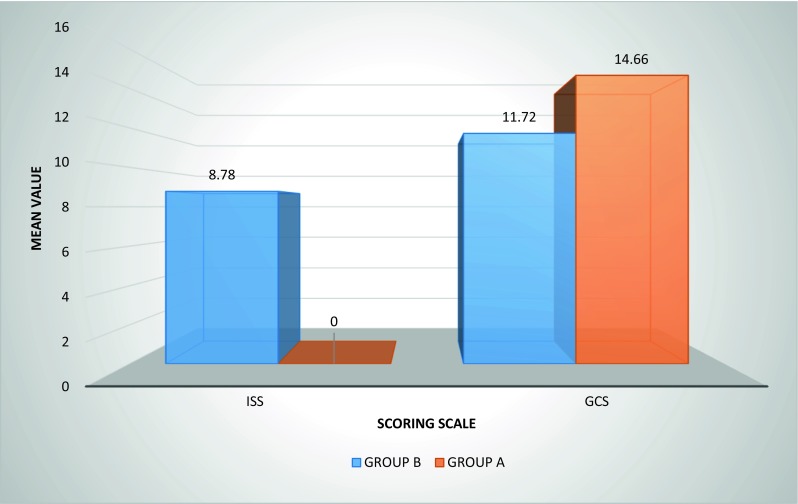

A total of 300 patients of maxillofacial trauma were included in the study, the age range being wide from 1 to 75 years. The mean age of males and females in the study was 31.6 and 32.1 years respectively with the majority of the victims in the age group of 20–29 years. This study observed a male predominance with 273 men (91%) and 27 women (9%). The most frequent cause of poly-trauma noticed was Road traffic accident as seen in 279 cases (93%) followed by self-fall observed in 12 cases (4%) and assault was the cause in 9 cases. (3%). Mandible was the most common bone involved in maxillofacial fractures [135(45%)] followed by zygomatic complex fractures [90(30%)]. 162 patients (54%) sustained concomitant injuries to other organ systems. In the patients with concomitant injuries, 97 patients sustained head injuries (60%), 62 patients had orthopedic injuries (38%) and only 3 patients had injuries to the abdomen (2%). The descriptive details of the patients included in the study are presented in Table 1. Pneumocephalus was the most common head injury observed. Cervical spine fractures which can be a cause of morbidity in head and neck trauma were seen in only six patients. Injuries to the chest wall were seen in six patients which was complicated by a haemothorax (Fig. 1). The mean GCS value in the patients of group A was 14.66 while the patients of Group B had a mean GCS value of 11.72 and a mean ISS value of 8.78 (Fig. 2). Death due to trauma occurred in two patients, both due to concomitant head injury.

Table 1.

Descriptive details of patients included in the study

| Gender | N | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 273 | 91 |

| Female | 27 | 9 |

| Age group | ||

| 0–9 | 3 | 1 |

| 10–19 | 27 | 9 |

| 20–29 | 117 | 39 |

| 30–39 | 93 | 31 |

| 40–49 | 27 | 9 |

| 50 and above | 33 | 11 |

| Etiology | ||

| Road traffic accident | 279 | 93 |

| Self fall | 12 | 4 |

| Assault | 09 | 3 |

| Facial bone affected | ||

| Mandible | 135 | 31 |

| Zygomaticomaxillary complex | 90 | 21 |

| Maxilla | 57 | 13 |

| Frontal | 51 | 12 |

| Isolated zygomatic bone | 45 | 10 |

| Isolated zygomatic arch | 39 | 9 |

| Nasal | 15 | 3 |

| Associated injuries to other organ system | ||

| Head injuries | 97 | 32 |

| Orthopaedic injuries | 62 | 21 |

| Abdominal injuries | 03 | 1 |

| Absent | 138 | 46 |

Fig. 1.

Types of associated injuries

Fig. 2.

Comparison of mean GCS and ISS values of group A and group B

Discussion

Road traffic accidents was the most common mechanism of injury in our study which is consistent with the findings of several other studies [3–5]. The second most frequent cause of trauma was self-fall followed by inter-personal violence. Scherbaum Eidt et al. also confirmed this finding in their study [6].

Another evident observation is that there is a 91% male preponderance in the study sample. This result can be affirmed by the observations of Kamath et al. [7] The overall male to female ratio observed in this study was as high as 10.1:1. The reason men are more exposed to the trauma, may be due to the fact that men are more frequently involved than women, in the activities of driving vehicles, playing serious sports, and in social events such as parties where consumption of alcohol, leads to a state of inebriation that in many cases, has been the catalyst for road accidents.

This study has showed that the majority of the victims were in the age group of 20–29 as this age group apparently is highly active outdoors. The mean age of males and females in this study is 31.6 and 32.1 years respectively. This average is corroborated by other reports in literature [7].

Excessive consumption of alcohol is strongly associated with facial injuries [8–10]. In this study, 80% of the patients were found to be in an intoxicated condition at the time of accident. Alcohol impairs judgment, brings out aggression, often leads to interpersonal violence, and is also a major factor in motor vehicle accident [11].

A total of 432 fractures of maxillofacial skeleton is observed in this study. The mandible was more frequently involved bone in the maxillofacial skeleton (45%), followed by the zygomatico-maxillary complex (30%). Haug et al. [12] in their survey observed that of 402 patients, 67% suffered mandibular fractures, 21% zygomatic fractures and 11% maxillary fractures. Obuekwe et al. [5] found that the mandible was the most common site of fracture, followed by the middle third of the face which included the zygomatico-maxillary complex. The results of this study therefore correlate with previous literature that fractures of the mandible represent the most common maxillofacial injury. This can be explained by the prominent size and position of the mandible making it more susceptible to injury. In the mandible, the fracture of the para-symphysis was more common. A similar observation has been reported in literature [4, 7, 13].

The associated injuries with maxillofacial trauma were seen in 162 patients (54%). The most frequent associated injury with maxillofacial trauma in this study is observed to be head injury (60%) followed by orthopedic injuries (38%). This finding is in concordance with the observations of several other authors in literature [5, 6]. Contradictory observations in the incidence of associated injuries, with the limb injuries occurring more frequently than the head injuries is observed in literature [14]. This may be due to the differences in the predominant means of transportation in the population [3]. Holmes et al. [15] observed that in patients who sustained maxillofacial fractures, neurologic injuries were the most frequent concomitant injury in the all-terrain vehicle group, whereas orthopedic injuries occurred more often in the motorcycle group.

The number of patients who sustained head injuries in this study was greatly observed to be associated with the fractures of the upper and middle third of the face as compared to the lower third of the face. Of the 97 patients with head injury, 67 cases were seen in patients with isolated mid-face fractures, 21 cases were seen with frontal bone fracture and only 9 cases of isolated mandible fracture were associated with head injuries. This observation concurs with the findings of several other authors in literature [16–18]. Udeabor et al. [17] attributed this to the proximity of the mid-face to the contents of the cranium. Hampson [19] reported that the tolerance of the mid-facial bone to force is lower than that of the frontal and mandibular bones thereby allowing the transmission of force to the base of the skull and cranium. It has been observed that the multiple mid-facial fractures were associated with 1.6-fold risk of traumatic head injuries [20]. Therefore, all the patients of maxillofacial trauma, especially involving the middle and upper third of the face should be considered a potential head injury patient until otherwise proven by CT scan. A repeat CT scanning of the brain should also be performed whenever remediable intracranial injury (secondary brain injury) is suspected based on clinical signs and symptoms exhibited by the patient [21]. Severe head injury was detected in two of the patients with GCS score of 3–5 with both the patients having sustained multiple intra-parenchymal contusions. Moderate head injury was detected in patients with a GCS score of 9–12. No head injury was observed in patients with a GCS score above 12. This finding concurs with other reports in literature [22]. But, it has been suggested that even with a GCS of 15 and no clinical findings indicating head injury, head injury maybe suspected in patients with multiple facial fractures [23].

In the orthopedic injuries recorded, the clavicle fracture was the most common (33%) followed by the fracture of the femur (19%). This observation although concurs with the findings in literature [6] differs from the observations of other authors who found the fracture of lower limb to predominate [3, 13, 14]. Brasileiro et al. [23] observed prevalence for injuries to the upper limbs followed by the lower limbs. This difference may be because of the mechanism of the fall and the site of the body which received the maximum impact.

In our study, Injury to the spine was recorded in 3.7% of cases with associated injuries, all of them at the cervical level. This finding is similar to the observations of other authors in literature [24–27]. Akama et al. [14] reported an incidence of 9.2% and stated that this type of fracture is critical as it can lead to serious consequences if neglected during the primary survey. In this study, the cervical spine injury was seen in patients who figured in road traffic accidents. It is observed to occur in association with a mandibular fracture in all the cases and the spine injury involved the region of C1, C2 in two cases and the region of C7 in four cases. This finding is supported by the observations of Ardekian et al. [28]. In our study, the patients were not given cervical spine immobilization during transit of the patient from the site of accident to the hospital due to lack of facilities in the ambulance and/or due to ignorant paramedical staff. Though, this did not lead to any grave consequences in the cases, it is important to note that the cervical spine trauma can be missed, especially when pain from other parts of the body dominates [29]. Cervical spine immobilization should never be removed until cervical spine injury has been excluded using a CT scan/lateral X-ray of cervical spine and extreme caution should be taken in maneuvering the unconscious, sedated or non-alert patients who are suspect of cervical spine injury [21].

Rib fractures with hemo-thorax was observed in only 2% in this study, which is similar to the findings of other authors in literature [5, 6, 9]. The ribs were fractured between the 4th–8th ribs in this study. Fractures of upper ribs indicate major trauma and should arouse suspicion of damage to adjacent structures such as lungs, subclavian vessels and brachial plexus [30].

The frequency of abdominal injuries in this study is 2%. The cause of the injury was a road traffic accident in which the patient had sustained injuries to the chest wall and upper extremity as well. This finding coincides with the observations of Gad et al. [31] who found that the Vehicle accidents are a common cause of blunt abdominal trauma usually associated with an injury was to an extremity. Bowley et al. [32] observed that in the lateral impact of collisions in road traffic accidents, the victim is accelerated away from the side of the vehicle which may result in, intra-abdominal solid organ injury and diaphragmatic rupture. The assessment for probable abdominal injury is not to be missed during the primary evaluation of a patient of trauma as this might be the reason for fatality. Most of the abdominal injuries are blunt injuries which are not obviously seen and this recommends the need to make the Ultrasound of abdomen a routine investigation in trauma patient.

Z-test results in this study show that there is a highly significant statistical difference in the mean ISS and GCS values between the patients who sustained associated injuries along with maxillofacial trauma and those without associated injuries (p < 0.001), with the values being higher and lower respectively in patients with associated injuries, indicating that the morbidity of the patients with associated injuries is higher as compared to those patients with facial trauma alone. This observation is in concordance with other reports in literature [15].

The mortality rate in the study is 0.66% with both the patients sustaining middle and upper third fractures of the maxillofacial skeleton with associated head injuries and having lower GCS and higher ISS values. This is similar to the observations of Plaisier et al. [16] who observed a lower GCS and higher ISS values in non-surviving patients who exhibited a dramatic predilection for mid- and upper facial fracture patterns.

Through this study, it is observed that the major cause of poly trauma is the road traffic accident (RTA). This leads to the inference that there is the need for implementation of stringent road safety measures which include speed limitation, ordinance on mandatory donning of helmet and seat belt apart from providing geometrically designed roads of improved quality.

Two major conclusions may be drawn from this study. Firstly, this study stresses on the need for the adherence to traffic rules and regulations, planning of scientifically and geometrically designed, good quality roads of high standards. Despite the existing traffic rules, the people and concerned authority don’t comply and strictly adhere to the traffic rules, leading to high rate of RTA.

Further, the role of the paramedical staff that transfers the patients from the site of accident to the hospital cannot be underestimated. It is imperative that the trauma victim be transferred to the definite emergency care of a hospital as soon as possible. The primary care provided during the transit period is of utmost importance, which mandates that the paramedical staff be cognizant of the primary care protocol. In the present scenario, especially in developed countries where the management of RTA patients has reached a new level, the emphasis is not just on the survival of accident victims but on maintaining quality of life post RTA. In developing nations like, India, the prevention of mortality of an RTA patient is the prime concern not taking into consideration the quality of life post RTA. That’s why the need for a swift emergency team response with deft paramedical staff cannot be overemphasized. Any delay in the emergency team arriving at the accident zone only aggravates the mortality and morbidity rate. The emergency control facilities provided in rural areas of north Karnataka need improvisation with more infusion of qualified paramedical team. Every trauma patient must be considered as a victim of potential cervical spine fracture and be managed accordingly to prevent debilitating complications. All these measures if undertaken, may aid in reducing the rate of morbidity and mortality due to Road Traffic Accident’s to less than half or even lower levels.

Secondly, this study suggests that it is incorrect to view the fractures to the facial skeleton as an isolated one, because, it is, as evidentially established in this study, associated with more grave, and sometimes fatal injuries that require thorough evaluation for multisystem trauma at the time of presentation. Surgical management of multiple traumatized patients with head and neck trauma is highly individualized and depends on a number of factors including etiology, concomitant injuries, age of the patient, and the possibility of an interdisciplinary procedure. This study facilitates a conclusion that knowledge of the associated injuries ensures proper care and faster recovery. Only a multidisciplinary and coordinated approach can vouch for optimum success in the treatment of patients with facial fractures with associated injuries.

Conflict of interest

All the above mentioned authors declare that, he/she do not have any conflict of interest. All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Down KE, Boot DA, Gorman DF. Maxillofacial and associated injuries in severely traumatized patients: implications of a regional survey. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;24:409–412. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Association For Automotive Medicine (1985) The Abbreviated Injury Scale. Arlington Heights. American Association for Automotive Medicine, Arlington Heights, IL, USA

- 3.Ajike SO, Adebayo ET, Amanyiewe EU, Ononiwu CN. An epidemiologic survey of maxillofacial fractures and concomitant injuries in Kaduna, Nigeria. Niger J Surg Res. 2005;7(3):251–255. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan M, Din QU, Murad N, Shah SMA. Maxillofacial and associated fractures of the skeleton—a study. Pak Oral Dent J. 2010;30(2):313–316. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obuekwe ON, Etetafia M. Associated injuries in patients with maxillofacial trauma. Analysis of 312 consecutive cases due to road traffic accidents. JMBR Peer Rev J Biomed Sci. 2004;3(1):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherbaum Eidt JM, De Conto F, DeBortoli MM, Engelmann JL, Rocha FD. Associated injuries in patients with maxillofacial trauma at the Hospital São Vicente dePaulo, Passo Fundo, Brazil. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2013;4(3):1–8. doi: 10.5037/jomr.2013.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamath RA, Bharani S, Hammannavar R, Ingle SP, Shah AG. Maxillofacial trauma in Central Karnataka, India: an outcome of 95 cases in a Regional Trauma Care Centre. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2012;5(4):197–204. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1322536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagov L, Rubiev M, Deliverska E. The role of alcohol involvement in maxillofacial trauma. J IMAB Annu Proc Sci Pap. 2012;18(2):147. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leles JLR, Santos ÊJD, Jorge FD, Silva ETD, Leles CR. Risk factors for maxillofacial injuries in a Brazilianemergency hospital sample. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010;18(1):23–29. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572010000100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ascani G, Di Cosimo F, Costa M, Mancini P, Caporale C (2014) Maxillofacial fractures in the province of Pescara, Italy: a retrospective study. ISRN Otolaryngol 2014(Article ID 101370):4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Al Ahmed HE, Jaber MA, Abu Fana SH, Karas M. The pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: a review of 230 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2004;98:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haug RH, Prather J, Indresano AT. An epidemiologic survey of facial fractures and concomitant injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:926–932. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90004-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Punjabi SK, Khan M, Qadeer-ul-Hassan ZUN. Associated injuries with facial trauma—a study. Jlumhs. 2012;11(2):60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akama MK, Chindia ML, Macigo FG, Ghuthua SW. Pattern of maxillofacial and associated injuries in road traffic accidents. East Afr Med J. 2007;84:287–290. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v84i6.9539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes PJ, Koehler J, Jr, McGwin G, Rue LW., III Frequency of maxillofacial injuries in all-terrain vehicle collisions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:697–701. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plaisier BR, Punjabi AP, Super DM, Haug RH. The relationship between facial fracturesand death from neurologic injury. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:708–712. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.7250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Udeabor S, Akinmoladun VI, Olusanya A, Obiechina A. Pattern of midface trauma with associated concomitant injuriesin a Nigerian Referral Centre. Niger J Surg. 2014;20(1):26–29. doi: 10.4103/1117-6806.127105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keenan HT, Brundage SI, Thompson DC, Maier RV, Rivara FP. Does the faceprotect the brain? A case control study of traumatic brain injury and facialfractures. Arch Surg. 1999;134:14–17. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampson D. Facial injury: a review of biomechanical studies and test procedures for facial injury assessment. J Biomech. 1995;28:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H-H, Liu Q, Yang R-T, Li Z, Li Z-B. Traumatic head injuries in patients with maxillofacial fractures: a retrospective case–control study. Dent Traumatol. 2015;31:209–214. doi: 10.1111/edt.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peter ward booth, Stephen A Schendel, Jarg-Erich Hausamen. vol 1, 2nd edn. p 13

- 22.Işik D, Gönüllü H, Karadaş S, Koçak ÖF, Keskin S, Garca MF, Eşeoğlu M. Presence of accompanying head injury in patients with maxillofacial trauma. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2012;18(3):200–206. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2012.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brasileiro BF, Passeri LA. Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures in Brazil: a 5-year prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2006;102:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorén H, Snäll J, Salo J, Suominen-Taipale L, Kormi E, Lindqvist C, Törnwall J. Occurrence and types of associated injuries in patients with fractures of the facial bones. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(4):805–810. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roccia F, Cassarino E, Boccaletti R, et al. Cervical spine fractures associated with maxillofacial trauma: an 11-year review. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1259. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e31814e0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elahi MM, Brar MS, Ahmed N, et al. Cervical spine injury in association with craniomaxillofacial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:201. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000293763.82790.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merritt RM, Williams MF. Cervical spine injury complicating facial trauma: incidence and management. Am J Otolaryngol. 1997;18:235. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(97)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ardekian L, Rosen D, Klein Y, Peled M, Michaelson M, Laufer D. Life-threatening complications and irreversible damage following maxillofacial trauma. Injury. 1998;29(4):253–256. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(98)80200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hackl W, Hausberger K, Sailer R, Ulmer H, Gassner R. Prevalence of cervical spine injuries in patients with facial trauma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2001;92:370–376. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.116894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaiswal A, Tanwar YS, Habib M, Jain V. First rib fractures: not always a hallmark of severetrauma a report of three cases. Chin J Traumatol. 2013;16(4):251–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gad MA, Saber A, Farrag S, Shams ME, Ellabban GM. Incidence, patterns, and factors predicting mortality of abdominal injuries in trauma patients. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4(3):129–134. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.93889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowley D, Boffard K (2002) Pattern of injury in motor vehicle accidents. World Wide Wounds