Abstract

Background

Presence of head injuries in patients with maxillofacial trauma is a lifethreatening condition. Prompt determination of head injury in these patients is crucial for improving patient survival and recovery. Hence, the need to know about the incidence of head injuries associated with maxillofacial trauma becomes an important aspect.

Materials and Methods

A total of 100 patients were included in the study. Patient with head injuries associated with maxillofacial fractures was accounted to determine the incidence and pattern of head injuries accompanying maxillofacial trauma. They were evaluated for epidemiological demographic and clinical characteristics.

Results

The present study had 91% predominance of male patients with age ranging from 1 to 75 years. 91% cases were as a result of RTA. The most frequent maxillofacial injury represented was the fractured mandible. The incidence of head injuries associated with maxillofacial trauma was 67 %. Among all the patterns of head injuries, concussion was the most common head injury associated with maxillofacial trauma.

Conclusion

In our study, the risk of head injury increased significantly as the Glasgow Coma Scale score decreased and with increase in the number of facial fractures. There was association between head injury and maxillofacial trauma.

Keywords: Facial fractures, Incidence, Head injury

Introduction

Maxillofacial injuries may be limited to superficial lacerations, abrasions over the face and also may be associated with multiple injuries to the head, chest, abdomen, cervical spine or extremities [1–3].

The closeness of maxillofacial bones to the cranium would suggest that there are chances of cranial injuries occurring simultaneously [4–6]. Historically, the facial architecture has been perceived to be a cushion against impact, protecting the neurocranium from severe injury [2, 7]. However, some recent investigations have suggested that the face may actually transmit forces directly to the neurocranium, resulting in more serious brain injuries [8–12].

In view of this, it is essential that the practicing surgeon be aware of the consequences of the associated head injuries and also their management. This study therefore evaluates the individuals with traumatic injuries to the maxillofacial skeleton from different mechanisms to calculate the incidence of head injury associated with it, the type of head injury and the role of the maxillofacial surgeon in identifying this comorbid condition.

The aim of the present study was to determine the incidence and pattern of head injuries accompanying maxillofacial trauma as assessed by oral and maxillofacial surgeon in patients who sustained maxillofacial fractures, with the objective to assess the lifethreatening conditions in cases of head injury accompanying maxillofacial fractures under neurological service, to document the incidence and features of associated head injuries with maxillofacial trauma and to evaluate the pattern of head injuries in patients with maxillofacial trauma and relationship between them.

Patients and Methods

A total of 100 patients who were the victims of maxillofacial trauma reporting to the emergency department of Basaveshwar Teaching and General Hospital (Tertiary hospital), Kalaburagi, Karnataka, were included in our prospective study conducted over a period of 1 year between September 2012 to August 2013

The age, gender, etiology of trauma and maxillofacial injuries of the patients were recorded using a standard proforma devised for the study. The maxillofacial fractures were classified based on the location such as nasal fracture, maxillary fracture, mandibular fracture, frontal bone fracture, lower orbital rim fracture and zygomatic fracture which were diagnosed by a primary clinical examination supported by a CT scan.

Patient with head injuries associated with maxillofacial fractures was also accounted to determine the incidence and pattern of head injuries accompanying maxillofacial trauma.

The patients were also assessed for any associated head injury if any. Injuries to the brain were suspected clinically by Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and confirmed by the CT scan, which was also used to diagnose any spine injuries.

Results

A total of 100 patients who reported to the emergency unit (casualty) at Basaveshwar Teaching and General Hospital, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, with a varied history of trauma ranging from simple fall to road traffic accident (RTA) were examined.

Patients of maxillofacial fractures with associated head injuries were further categorized into four groups:

Cases which return to normal conscious level within 6 h were classified as concussion injury and cerebral edema.

Intracranial hematoma group: Cases with subarachnoid hematoma, subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma and intracerebral hemorrhage.

Skull fracture group: Cases with pneumocephalus and skull base fractures.

Cerebral contusion group: Cases with cerebral contusion and laceration.

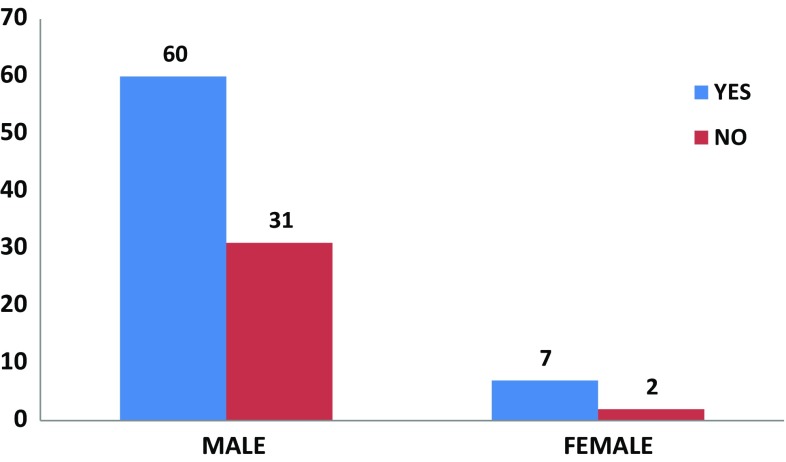

The demographic profile revealed the distribution of head injury according to sex showing 91 male patients and 9 female patients. Out of these patients, 60 males and 7 female patients had concomitant head injury (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of head injuries according to sex

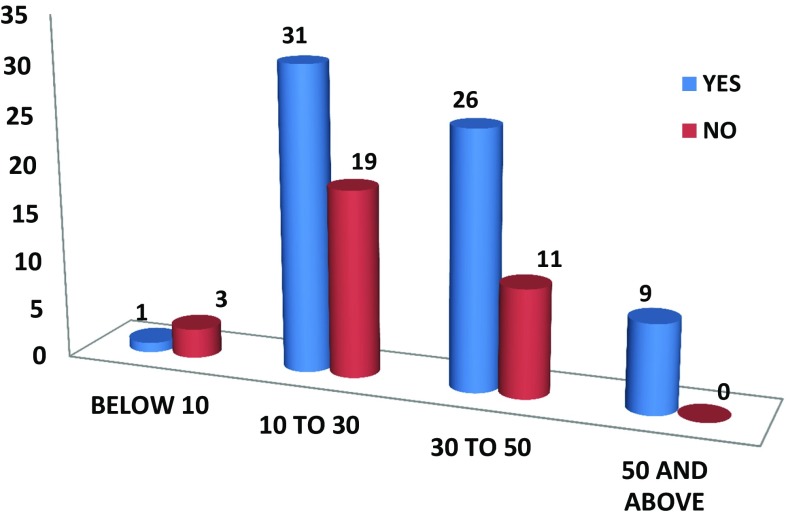

The age of the patients ranges from 1 to 75 years, with mean age 31.14 years. Patients were divided into four age groups: group I: below 10 years, group II: 10–30 years, group III: 30–50 years and group IV: 50 years and above. Majority of the patients were in the age group of 10–30 years accounting for 50 patients out of which 31 patients had concomitant head injury. Only 1 out of 4 patients in the age group of below 10 years, 26 out of 37 patients in the age group of 30–50 years and all the 9 patients in the 50 years and above age group had concomitant head injury (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of head injuries according to age

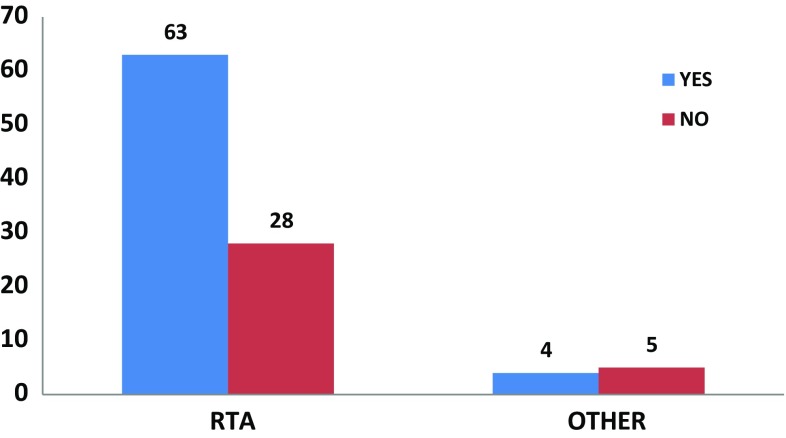

RTA is the leading cause for all maxillofacial traumas. There were 91 patients who allegedly met in RTA out of which 63 patients had concomitant head injury. The other causes of maxillofacial trauma such as self fall, assault, pressure cooker blast, bullock cart hit accounted for only 9 patients out of which 4 had concomitant head injury (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of head injuries according to etiology

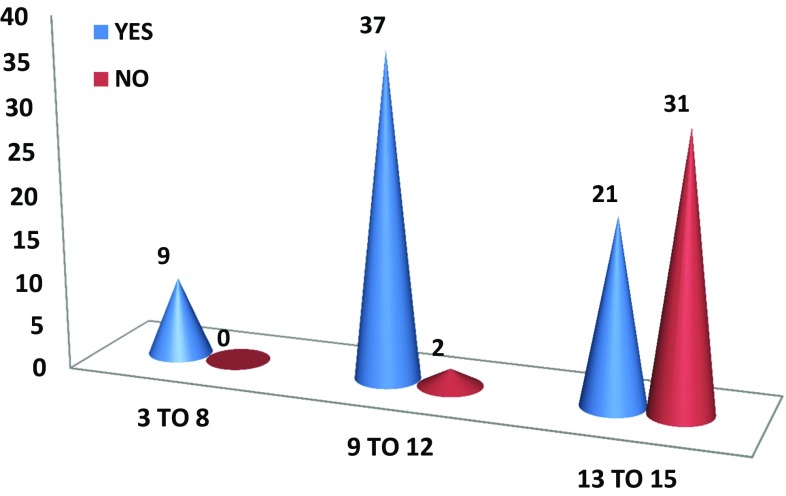

Based on Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scoring, the patients were categorized into three groups: group I: 3–8 score, severe head injury; group II: 9–12 score, moderate head injury; and group III: 13–15 score, mild head injury. Based on these scoring, severe head injury was detected among 9 patients, moderate head injury in 37 out of 39 patients and mild head injury in 21 out of 52 patients. The risk of head injury increased significantly as the GCS score decreased (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of head injuries according to GCS

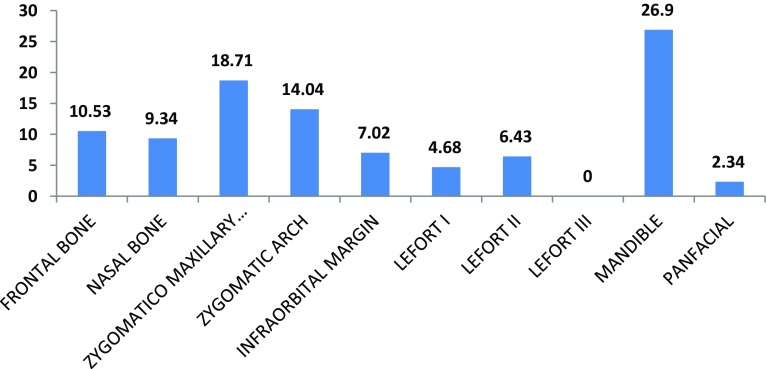

A total of 171 fractures of maxillofacial skeleton were reported. The most frequent maxillofacial injury represented was the fractured mandible 46 (26.90%) followed by fractured zygomatico-maxillary complex 32 (18.71%), zygomatic arch 24 (14.04%) and frontal bone 18 (10.53%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Different types of maxillofacial injuries (in %)

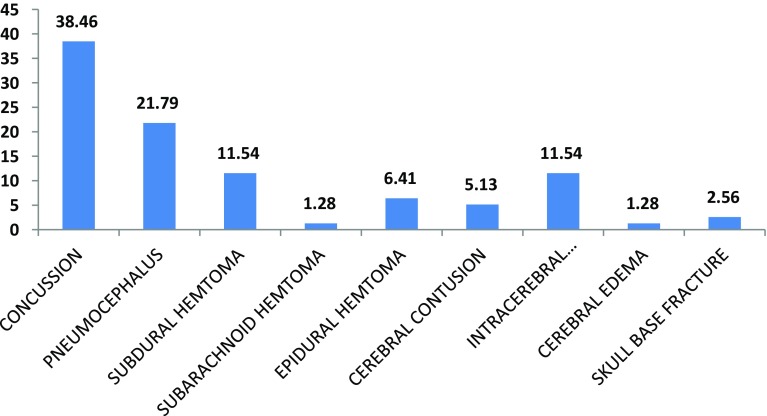

Among all the patterns of head injuries, concussion accounting for 38.46% was the most common head injury associated with maxillofacial trauma followed by pneumocephalus 21.79%, subdural hematoma and intracerebral hemorrhage 11.54% each (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Different types of head injuries (in %)

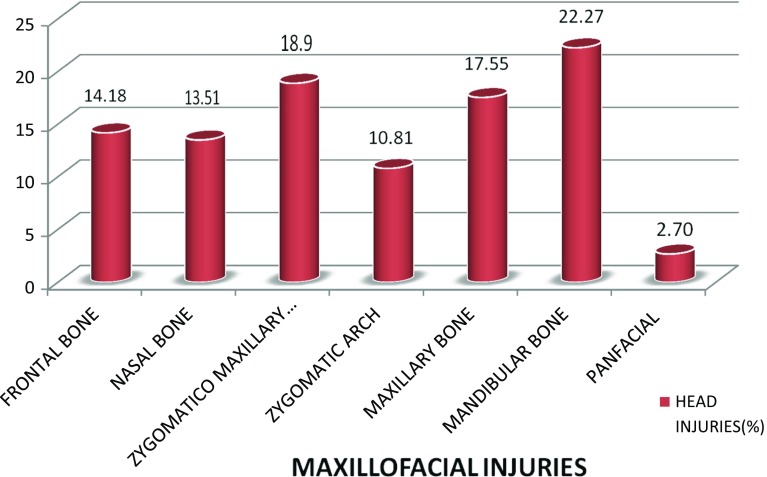

Among all patterns of maxillofacial fractures, mandible fracture was associated with 22.27% head injury, followed by fractures of zygomatico-maxillary complex (ZMC) fracture 18.9%, maxilla 17.55% and frontal bone 14.18% (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Distribution of head injuries associated with maxillofacial injuries

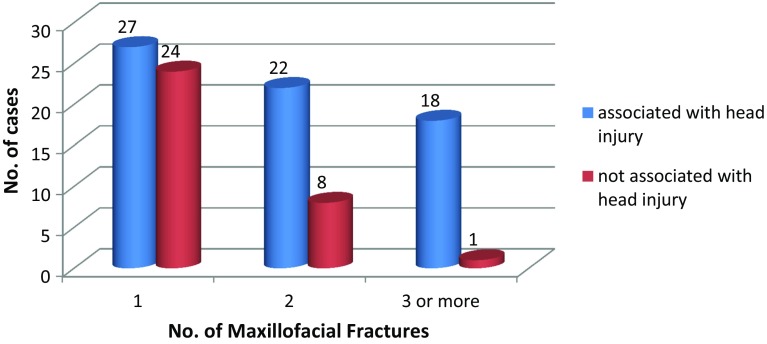

In our study, 27 out of 51 patients (54%) had head injuries associated with only one maxillofacial fracture. A total of 22 out of 30 patients (73.33%) had head injuries associated with two maxillofacial fractures. Eighteen out of 19 patients (94.73%) had head injuries were associated with three and more maxillofacial fractures. The risk and severity of head injury increased as the number of facial fractures increased. There is significant association of head injuries with maxillofacial trauma (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Association between maxillofacial injuries and head injuries

Discussion

Global mobilization and urbanization has led to the emergence of trauma as one of the leading health problems, with maxillofacial trauma being no exception. Nowadays, facial injuries have become a quotidian situation in the emergency rooms as the face is highly vulnerable to trauma due to the fact that it is the most exposed region of our body. Injuries can be incurred in situations such as the road traffic accidents, fall from height, interpersonal violence, animal attacks and sports. Facial trauma many a times occur in association with injuries to other organ systems of the body, and in such cases, there is an increase in the morbidity levels, demanding immediate intervention and management.

The spectrum of maxillofacial injuries presenting in the trauma unit ranges from dento-alveolar fractures, nasal bone fractures, mandibular fractures, maxillary fractures, frontal bone fractures, naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures, panfacial fractures to penetrating injuries. Patients with maxillofacial fractures may have concomitant intracranial, pulmonary, intra-abdominal or extremity injuries [3–5].

While nature has protected the brain with a complete helmet of thick bone of great strength, the bony areas of the face (concerned with vision, taste, smell, mastication and cosmetics) are more fragile [4]. It has been proposed that the face may protect the brain from injury the way an airbag protects the chest in a motor vehicle crash. In many countries, cranial injury have been found to be the most common accompanying organ injury in patients with maxillofacial trauma which includes head traumas, intracranial hemorrhages, closed head traumas (brain contusion or laceration) and skull fracture [5, 6]. A close relationship between maxillofacial fracture and intracranial injury has also been reported in the literature [4–6, 13, 15].

Generally, the presence of amnesia, emesis, vomiting, loss of consciousness or a low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score is important findings for suspicion of a cranial injury [14]. However, in patients with maxillofacial trauma, head injuries may be seen without observing these findings [14, 15]. Presence of head injuries in patients with maxillofacial trauma is a lifethreatening condition increasing the mortality [13, 14]. But, according to Fonseca et al. [16], the exact relationships between different types of facial fractures and brain injuries have not been firmly established in studies yet.

Males comprised the majority of patients accounting for 91 %, with females only 9 % in the study. The calculated Chi-square value was 0.12(< 3.84 for p = 0.05) indicating no significant association between sex of the patient and head injuries. This significant gender distribution seems to correlate with other studies reviewed in the literature showing male predominance ranging from 80 to 90 % by various authors. The overall male-to-female ratio was as high as 10.1:1. This correlates with the studies done by Sajjad et al. [18] who reported as 9:1.

The age ranged from 1 to 75 year with the mean age 31.14 years. Majority of the patients in this study were found to be in 10–30 years of age group. The calculated Chi-square value was 8.37(> 7.81 for p = 0.05) indicating significant association between age and head injuries.

This correlates to studies reported in the literature [2, 17], but does not correlate to the studies conducted by Kloss et al. [15] in which they found no significant association between head injuries and age.

The etiology being road traffic accident in our study is consistent with the most of the studies reported [14, 17]. The calculated Chi-square value was 1.29(< 3.84 for p = 0.05) indicating no significant association between etiology and head injuries which correlates with study reported [14] but is in disagreement with studies reported [8, 19] which states that there is a statistical association between etiology and head injury.

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a scale which indicates the prognosis of traumatic patients. This scale is simple and fast in the scoring of traumatic patients in emergencies. GCS ranges from 3 to 15. Lower scores indicate worse prognosis. According to the studies, mortality of the patients with GCS 3–4 is about 90% [24]. Severe head injury was detected in all of the 9 patients with GCS score of 3–8. Moderate head injury was observed in 37 out of 39 (94.87%) patients with GCS score of 9–12 and mild head injury in 21 out of 52 (40.38%) patients with GCS 13–15. The risk of head injury increased significantly as the GCS score decreased in groups. In our study, there was statistical association between GCS and head injury where calculated Chi-square value was 34.79 (> 5.99 for p = 0.05) which correlates with the studies reported by Daphna IŞIK [14].

Head injury has been reported as associated with facial fracture in 5.4–87 % of patients [1, 4, 5]. This wide range is probably due to different selection criteria and methods of detecting brain injury. The incidence of head injuries associated with maxillofacial trauma in our study was 67 %, which is in agreement with the studies [1, 19] but is in contrast to various other studies [20, 21]. These conflicting results may be due to methodological differences between various studies or cultural and habitual differences in various populations being studied [20].

In neurological injuries, various studies show concussion with normal brain study (closed head injury) to be associated more frequently with facial fractures [1, 9, 13, 20, 28] Among all the patterns of head injuries, in the study group also had concussion (38 %) as the most common head injury associated with maxillofacial trauma.

In our study, mandible fracture in association with other maxillofacial fractures was mostly associated with concussion with normal brain study (closed head injury) and with other types of head injury accounting for 22.27 % correlating with studies reported in the literature [17, 22], followed by zygomatico-maxillary complex (ZMC) fracture 18.9 %, maxilla 17.55 % and frontal bone 14.18 %. There was increased risk of head injury with increase in number of fractures p value 16.29 (> 12.59 for p = 0.05). This result correlates with the studies reported [2, 14], but in contrast with study [8] in which they did not find increased risk of head injury with increase in number of fractures. They presumed that there might be a correlation between increased forces and rotational components to the cranial vault with an increased number of fractures to the facial bones.

Excessive consumption of alcohol is strongly associated with facial injuries [5, 25–28]. In our study, 80% of the patients were under alcohol influence. The higher consumption of alcohol and substance abuse has further enhanced the statistical record of RTAs in our country. Alcohol impairs judgment, brings out aggression, often leads to interpersonal violence, and is also a major factor in motor vehicle accident. Al Ahmed et al. [29] in a review of 230 cases of maxillofacial injuries in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, reported no cases were associated with alcohol abuse. This discrepancy may be explained by differences between one country and another, in the strictness of laws governing the sale and consumption of alcohol which may be effective in preventing alcohol-related injuries.

In our studies, we reported 4 cases of children, out of which only one had severe head injury with GCS score of 3. Various etiologies were self fall, hit by a bullock cart and RTA. Children are uniquely susceptible to craniofacial trauma because of their greater cranial to body mass ratio [30]. The reasons for the lower incidence of facial fractures in children can be concluded as the face is smaller in relation to the rest of the head, there is a lower proportion of cortical bone to cancellous bone in the children’s faces, poorly developed sinuses make the bones stronger, and fat pads provide protection for the facial bones [31, 32].

In our study, we found statistical association between head injury and maxillofacial trauma, p value 16.29 (> 12.59 for p = 0.05). The risk and severity of head injury increased as the number of facial fractures increased. In our study, facial fractures did not prevent head injuries but were markers for an increased likelihood of head injuries. This is in correlation with studies reported [8–11] but in contrast to studies [2, 23] who suggested that facial bones act as a protective cushion for the brain, explaining the fact that injuries that crush the facial bones frequently cause no apparent brain damage. Chang et al. [23] suggested that the maxilla, together with the neighboring bones, is capable of absorbing considerable impact force, thus protecting the brain from direct collision.

Through this study, it is observed that the major cause of head injury is the road traffic accident (RTA). This leads to the inference that there is the need for implementation of stringent road safety measures which include speed limitation, ordinance on mandatory donning of helmet and seat belt apart from providing geometrically designed roads of improved quality.

Secondly, this study suggests that it is incorrect to view the fractures to the facial skeleton as an isolated one, because, it is, as evidentially established in this study, associated with more grave, and sometimes fatal head injuries require thorough evaluation at the time of presentation. Surgical management of such traumatized patients with head and neck trauma is highly individualized and depends on a number of factors including etiology, concomitant injuries, age of the patient and the possibility of an interdisciplinary procedure. This study facilitates a conclusion that knowledge of the associated injuries ensures proper care and faster recovery. Only a multidisciplinary and coordinated approach can vouch for optimum success in the treatment of patients with facial fractures with associated injuries.

Conclusion

Maxillofacial injuries are one of the common features of road traffic accidents (RTA) and other means of trauma, with the head and face being the first part of the body acting as a secondary missile during ejection from a motor vehicle. In motor vehicle accidents, the head is often subjected to forces in multiples of that of gravity.

Head injuries are more serious consequences usually associated with such incidents which need to be attended earlier. In this prospective study, there was a significant association between head injuries and maxillofacial trauma. The risk of head injury increased as the number of maxillofacial fractures increased and the GCS decreased.

Hence every maxillofacial fracture patient must be carefully evaluated clinically and radiologically to rule out any underlying head injury and to decrease the incidence of mortality rate. Quick diagnosis and early intervention are fundamental to prevention of morbidity as well as mortality especially with regard to prevention of traumatic brain injury (TBI) as even a short duration of hypoxia and edema will lead to significant permanent neurological deficits.

Hence this study which intends to analyze the incidence of head injuries is very important and recommended. More research into the mechanism of force transduction, additional risk factors for minor brain injury and long-term functional consequences clearly is needed.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Luce EA, Tubb TD, Moore AM. Review of 1,000 major facial fractures and associated injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:26–30. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee KF, Wagner LK, Lee YE, Suh JH, Lee SR. The impact-absorbing effects of facial fractures in closed-head injuries: An analysis of 210 patients. J Neurosurg. 1987;66(4):542–547. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.4.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Follmar KE, Debruijn M, Baccarani A, Bruno AD, Mukundan S, Erdmann D, Marcus J. Concomitant injuries in patients with panfacial fractures. J Trauma. 2007;63:831–835. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181492f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim LH, Lam LK, Moore MH, Trott JA, David DJ. Associated injuries in facial fractures: review of 839 patients. Br J Plast Surg. 1993;46:635–638. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(93)90191-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvi A, Doherty T, Lewen G. Facial fractures and concomitant injuries in trauma patients. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:102–106. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200301000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulligan RP, Friedman JA, Mahabir RC. A nationwide review of the associations among cervical spine injuries, head injuries, and facial fractures. J Trauma. 2010;68:587–592. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b16bc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigaroudi AK, Saberi BV, Chabok SY. The relationship between mid-face fractures and brain injuries. J Dent Shiraz Univ Med Sci. 2012;13(1):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidoff G, Jakubowski M, Thomas D, Alpert M. The spectrum of closed-head injuries in facial trauma victims: incidence and impact. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:6–9. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(88)80492-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keenan HT, Brundage SI, Thompson DC, Maier RV, Rivara FP. Does the face protect the brain? A case control study of traumatic brain injury and facial fractures. Arch Surg. 1999;134:14–17. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin RC, II, Spain DA, Richardson JD. Do facial fractures protect the brain or are they markers for severe head injury? Am Surg. 2002;68(5):477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraus JF, Rice TM, Peek-Asa C, McArthur DL. Facial trauma and the risk of intracranial injury in motorcycle riders. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:18–26. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajandram RK, Syed Omar SN, Rashdi MF, Jabar A, Nazimi M. Maxillofacial injuries and traumatic brain injury—a pilot study. Dent Traumatol. 2014;30:128–132. doi: 10.1111/edt.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gwyn PP, Carraway JH, Horton CE, Adamson JE, Mladick RA. Facial fractures-associated injuries and complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;47:225–230. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Işik D, Gönüllü H, Karadaş S, KOÇAK ÖF, KESKİN S, Garca MF, EŞEOĞLU M. Presence of accompanying head injury in patients with maxillofacial trauma. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2012;18(3):200–206. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2012.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kloss F, Laimer K, Hohlrieder M, Ulmer H, Hackl W, Benzer A, Schmutzhard E, Gassner R. Traumatic intracranial haemorrhage in conscious patients with facial fractures—a review of 1959 cases. J CranioMaxillofac Surg. 2008;36(7):372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonseca RJ, Walker RV, Norman BJ. Oral and maxillofacial trauma. 3. USA: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haug RH, Savage JD, Likavec MJ, Conforti PJ. A review of 100 closed head injuries associated with facial fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:218–222. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90315-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman SA, Chandrasala S. When to suspect head injury or cervical spine injury in maxillofacial trauma? Dent Res J. 2014;11(3):336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grant AL, Ranger A, Young GB, Yazdani A. Incidence of major and minor brain injuries in facial fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(5):1324–1328. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31825e60ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zandi M, Seyed Hoseini SR. The relationship between head injury and facial trauma: a case–control study. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;17:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s10006-012-0368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pappachan B, Alexender M. Correlating facial fractures and cranial injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(7):1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haug RH, Prather J, Indresano AT. An epidemiologic survey of facial fractures and concomitant injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:926–932. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90004-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang CJ, Chen YR, Noordhoff MS, Chang CN. Maxillary involvement in central craniofacial fractures with associated head injuries. J Trauma. 1994;37:807–811. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199411000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2(7872):81–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telfer MR, Jones GM, Shepherd JP. Trends in the aetiology of maxillofacial fractures in the United Kingdom (1977–1987) Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:250–255. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutchison IL, Magennis P, Shepherd JP, Brown AE. The BAOMS United Kingdom survey of facial injuries part 1: aetiology and the association with alcohol consumption. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(98)90739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchanan J, Colquhoun A, Friedlander L. Maxillofacial fractures at Waikato Hospital, New Zealand: 1989 to 2000. N Z Med J. 2005;118:1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason PN. Facial injuries. In: McCarthy JG, editor. Plastic surgery. Saunders: Philadelphia; 1990. pp. 868–872. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Ahmed HE, Jaber MA, Abu Fana SH, Karas M. The pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: a review of 230 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hassan NA, El Kelany RS, Emara AM, Amer M. Pattern of craniofacial injuries in patients admitted to Tanta University Hospital-Egypt. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010;17(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arabion HR, Tabrizi R, Aliabadi E, Gholami M, Zarei K. A retrospective analysis of maxillofacial trauma in Shiraz, Iran: a 6-year-study of 768 patients (2004–2010) J Dent Shiraz Univ Med Sci. 2014;15(1):15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fasola AO, Nyako EA, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Trends in the characteristics of maxillofacial fractures in Nigeria. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]