Abstract

Aim

Synovial chondromatosis (SC) is a benign condition that is characterized by the formation of cartilaginous nodules within the synovial tissue of a joint that may detach and form loose bodies inside the articular space. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the use of surgical arthroscopy for the treatment of SC of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Materials and Methods

A series of six patients treated with arthroscopy (one patient requiring an open arthrotomy due to the size of the loose bodies) in our centre between 1997 and 2016 is presented and results are discussed. A systematic review of the literature of patients with SC treated with arthroscopy or arthroscopy-assisted open arthrotomy is also carried out.

Results

Pain, which was the main symptom in our patients, and maximum mouth opening both improved significantly after surgical treatment. Three of the patients were diagnosed with primary SC, and the other 3 had a previous diagnosis of internal derangement. None of the patients showed signs of relapse during the follow-up period.

Conclusions

Surgical arthroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure that allows the extraction of loose bodies and even partial synovectomy of the affected membrane with good results and without recurrence of the disease. This technique can be useful in cases of SC with loose bodies measuring less than 3 mm or without extra-articular extension.

Keywords: Synovial chondromatosis, TMJ, Arthroscopy

Introduction

Synovial chondromatosis (SC) is described as a monoarticular benign metaplasia of the synovial membrane, characterized by the formation of cartilaginous nodules within the subsynovial connective tissue that may detach and form loose bodies inside the articular space. This condition mainly affects large joints such as the knee, elbow, wrist and hip, and has been studied well in these locations. Involvement of the TMJ is a rare condition with isolated case reports and small series of patients published in medical literature [1]. This non-neoplastic disorder of the TMJ affects women more frequently than men with a ratio of 4:1, and it is predominantly located in the right side, with a right-to-left ratio also of 4:1 [2]. When it occurs in the TMJ, it is usually confined to the articular space, although extra-articular extension to the infratemporal space, the parotid region or the middle cranial fossa has also been described [3–5].

The aetiology of this condition is still controversial, and both primary and secondary forms have been described [6]. In the primary form, a cartilaginous metaplasia of mesenchymal tissue remnants arises in the synovial membrane. Fibroblasts beneath the membrane surface become metaplasic and deposit chondromucin. Active cellular proliferation occurs and cartilage nodules grow and finally detach inside the joint space. Secondary SC is a more passive process where other causes such as trauma, inflammatory or degenerative arthritis or other joint diseases induce foci of cartilaginous metaplasia in the synovial membrane and nodule formation [6]. This secondary form is more frequent and less aggressive.

Clinical signs and symptoms such as preauricular swelling, unilateral pain, limitation of jaw motion, crepitation and occlusal changes are commonly seen in SC. However, these signs are non-specific and can be mistaken for an internal derangement, delaying treatment [7–9]. Conventional X-rays are usually normal, while computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might identify intraarticular loose bodies or even extra-articular extension [8, 10, 11].

SC is classified histologically in three phases according to the Milgram classification [12]: stage 1 or the early stage is the active phase characterized by an intrasynovial disease without loose bodies; stage 2 or the intermediate stage shows synovitis with osteochondral nodules in the synovial membrane and loose bodies within the joint; and stage 3 or the final stage is characterized by the presence of loose bodies without synovial involvement.

The standard treatment supported by most authors is open arthrotomy of the affected TMJ with removal of loose bodies and synovectomy if necessary. However, TMJ arthroscopy has gained popularity as a diagnostic and therapeutic option in SC [5, 7, 8, 13–15]. SC generally occurs in the superior joint space, which makes arthroscopic management feasible [15].

The objective of this article is to show that TMJ arthroscopy is a valid option of treatment in SC by presenting a series of six patients with no relapse during follow-up. A systematic literature review and analysis are also presented.

Patients and Methods

A series of six patients were treated with TMJ arthroscopy due to SC in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery of the University Hospital “La Princesa” (Madrid, Spain) between 1997 and 2016. Age, gender, medical history, previous treatments and possible aetiological factors (TMJ trauma, systemic joint inflammatory disorders, degenerative arthritis, TMJ internal derangements or bruxism) were recorded. Clinical signs (pain, swelling, limitation of mouth opening, lateral joint deviation and joint sounds) were also recorded. Two parameters were used for preoperative and post-operative evaluation of the technique: pain measured by a visual analog scale (VAS; range 0 to 100 mm) and maximum mouth opening (MMO in millimetres) for mandibular function. These two parameters were measured preoperatively and 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery. Panoramic X-rays and an MRI and/or CT scan were taken on each patient before surgery. The institutional review board of our centre approved this study.

Surgical Technique

Patients were surgically treated with a double-puncture TMJ arthroscopy under general anaesthesia and nasotracheal intubation. TMJ arthroscopy is performed with a Striker ® (Stryker Endoscopy, San Jose, CA) 1.9 mm and 30° arthroscope. After entering the upper joint space with a 23-gauge needle, distension of the joint space is obtained with saline solution. Using a sharp-tipped and then a blunt-tipped trocar, a puncture is carefully made in the superior compartment in order to introduce the arthroscope cannula. Continuous lavage with lactated Ringer’s solution is maintained using a 50-mL syringe connected to an irrigation line. After inspection of the upper joint space, a second cannula is inserted by puncture in the anterior recess by a method of triangulation.

Different arthroscopic procedures are performed depending on intraoperative arthroscopic findings: lysis–lavage and an initial diagnosis, electrocautery with the COBLATOR™ II Surgery System in areas of synovitis, motor debridement for irregularities of the articular surface, in addition to the removal of loose bodies that are sent to the Pathological Anatomy Department for evaluation. In cases of disc displacement, the posterior attachments are also electrocauterized with the COBLATOR™ II Surgery System. According to the protocol for TMJ arthroscopy followed in our centre, the procedure is always accompanied by the injection of sodium hyaluronate to ease articular mobilization. Milgram’s classification is used for staging of the patient12. During the first 6 months after the arthroscopy, all patients undergo physiotherapy that involves a programme of jaw exercises, with mandibular manipulation and joint mobilization, to be carried out at home.

In case of abundance and large-sized loose bodies, an open arthrotomy (by classic preauricular incision) is done in order to completely remove loose bodies.

A systematic review of English articles published in medical literature between 2007 and 2017 was carried out, with a search of patients diagnosed with TMJ synovial chondromatosis, and treated with arthroscopy or arthroscopy-assisted open arthrotomy. The search was done through PubMed and MEDLINE databases with the following keywords: [“synovial chondromatosis” or “synovial chondrometaplasia” or “synovial osteochondromatosis”] AND [“TMJ” or “temporomandibular joint”] AND [“arthroscopy” or “surgery”].

Results

Five of the six patients treated of SC were female, and all six of them had a unilateral involvement of the left TMJ. The average age was 42 years (range 33–57 yrs). None of the patients had a history of previous trauma or degenerative arthritis. Three patients were diagnosed with bruxism and were treated with occlusal splits previous to the surgery. They were also treated conservatively with a soft diet, joint rest and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These three patients (cases 1, 2 and 3) had an initial diagnosis of internal derangement and are considered secondary SC. The other three cases (cases 4, 5 and 6) had no previous history of TMJ disorder or previous treatments and are considered primary SC.

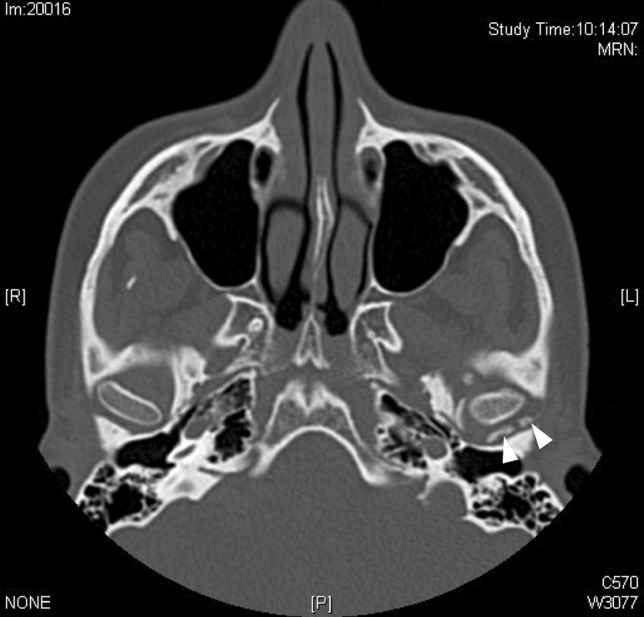

The most common presenting symptoms were preauricular pain and limitation of mandibular range of motion. Two patients presented swelling of the TMJ area. These clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Average preoperative pain was 46.7 mm (SD ± 27.3; VAS), and average preoperative MMO was 32.3 mm (SD ± 9). Cases 1, 4, 5 and 6 reported mild-to-moderate pain and also had a limitation of mouth opening. Case 3 complained severe pain but with no difficulty of mouth opening, and case 2 had mild pain with a normal mouth opening, and the presence of loose bodies was shown in the CT scan (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients, including preoperative pain and range of motion. (LD—lateral deviation, RLM—right lateral movement, LLM—left Lateral Movement, P—protrusion, C—conservative, DDwR—disc displacement with reduction, DDwoR—disc displacement without reduction)

| Sex, Age | Bruxism | Previous trauma | Use of occlusal splint | Duration of use (months) | Side affected | Preoperative pain (VAS) | Preoperative MMO | Clicking sounds | Preauricular swelling | LD | RLM | LLM | P | Previous treatment | Panoramic X-ray | MRI/CT scan findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F, 38 | Yes | No | Yes | 8 | Left | 10 | 20 | Yes | No | Left | 3 | 10 | 3 | C | Normal | |

| 2 | F, 37 | Yes | No | Yes | 21 | Left | 20 | 37 | Yes | No | Left | 7 | 10 | 6 | C | Normal | Perforated disc and 3 free bodies |

| 3 | F, 33 | Yes | No | Yes | 30 | Left | 80 | 46 | Yes | Yes | No | 12 | 12 | 10 | C | Normal | Effusion, synovitis and DDwR |

| 4 | F, 44 | No | No | No | No | Left | 50 | 30 | No | No | No | 4 | 4 | 4 | No | Normal | DDwoR and significant synovitis |

| 5 | M, 43 | No | No | No | No | Left | 70 | 35 | No | Yes | No | 6 | 15 | 8 | C | Normal | Effusion and synovitis |

| 6 | F, 57 | No | No | No | No | Left | 50 | 26 | Yes | No | Left | 3 | 9 | 5 | C | Normal | Effusion and DDwR |

Fig. 1.

CT scan image in which two intraarticular loose bodies (white arrowheads) are observed in the left TMJ

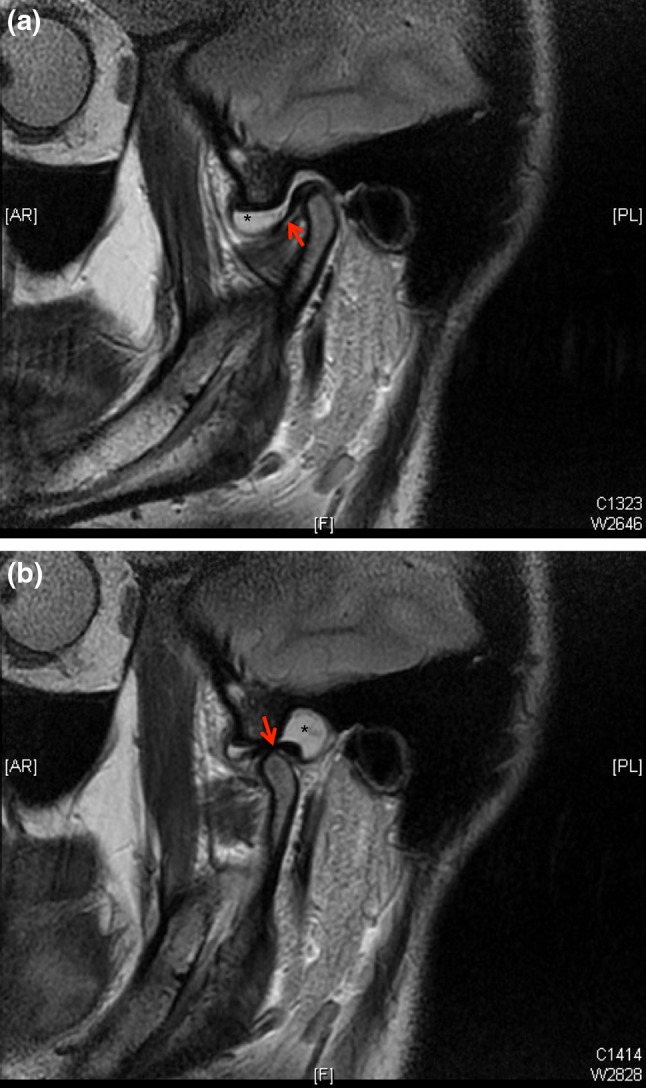

Conventional panoramic X-rays were normal in all six patients. TMJ magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was taken in five patients, with two cases of secondary SC and three cases of primary SC. Synovial effusion was present in 4 cases, 3 of which also had disc displacement (2 with reduction and 1 without) (Fig. 2). Case 1 had long-term TMJ disorder and a diagnostic TMJ arthroscopy was indicated.

Fig. 2.

T2-weighted magnetic resonance image in FSE sequence showing synovial effusion (asterisk) with mouth closed (a) and mouth open (b). Articular disc is marked with red arrows

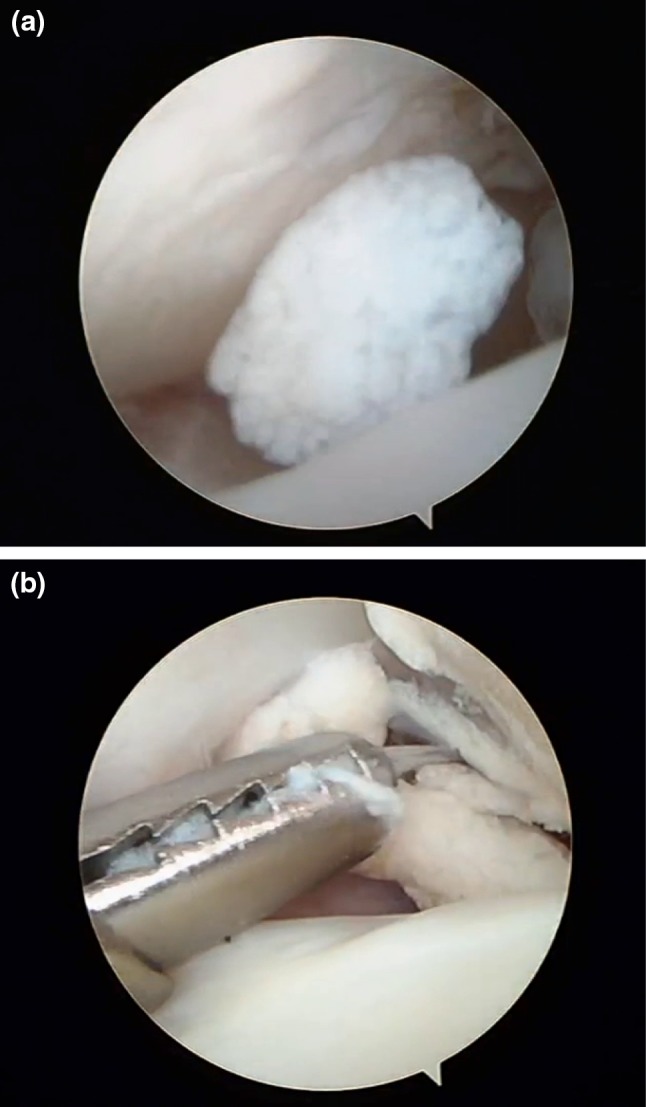

All of the patients were surgically treated with a TMJ arthroscopy under general anaesthesia. SC was identified in every case in the initial diagnostic phase of the procedure. Loose bodies measuring between 0.5 and 3 mm were observed in all six cases and were removed with a forceps from the superior joint space through a second cannula (Fig. 3). Different grades of synovitis and chondromalacia were also observed. Disc displacement was found in two cases, and disc perforation and degenerative changes were observed in another case. Electrocoagulation of areas of synovitis was performed, and the posterior ligament was also coagulated in cases of disc displacement to reposition the disc. A motorized shaver was used for the debridement of areas of chondromalacia if necessary. Arthroscopic findings and treatment manoeuvers are described in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Intra-articular arthroscopic images in which loose body is observed inside the superior joint space (a) and its capture with forceps (a)

Table 2.

Arthroscopic findings and treatment manoeuvers (L—left, Chondrom.—chondromalacia, N—normal, Perfor.—perforated, Electrocaut.—electrocautery, SC—synovial chondromatosis)

| Side | Synovitisa | Retrodiscal tissue | Chondromb | Bone | Roofing (%) | Disc | Adherence | Loose bodies | Lavage (ml) | Electrocaut. | Use of motor | Hyaluronic acid | SC stage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L | IV | Redundant | IV | Visible, coarse | 50 | N | No | Yes | 1550 | Yes | No | No | II |

| 2 | L | I | Degenerated | IV | Visible | Not assess. | Perfor. | Yes | Yes | 1700 | No | Yes | Yes | III |

| 3 | L | IV | Redundant with synovitis | II | Not visible | 100 | N | No | Yes | 700 | Yes | No | Yes | II |

| 4 | L | III | Synovitis | II | Eroded | 25 | Dull | No | Yes | 500 | Yes | No | Yes | II |

| 5 | L | IV | Synovitis | II | N | 50 | N | No | Yes | Surgery ends in open arthrotomy due to abundance of free bodies | II | |||

| 6 | L | I | Normal | II | Not visible | 100 | N | No | Yes | 800 | Yes | No | No | II |

aMcCain JP. Principles and Practice of Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopy. St. Lous: Mosby, pp 42–58,128–65, 1996

bQuinn JH. Pathogenesis of Temporomandibular Joint Chondromalacia and Arthralgia. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 1: 47, 1989

One case (case 2) showed loose bodies with only minimal synovitis (grade I), and so was diagnosed with stage 3 SC; the other five cases were diagnosed with stage 2 SC. Inferior joint space was unaffected in all six cases. Minor complications (extravasation of fluid to soft tissues) occurred in two patients, which resolved within 24–48 h. Open arthrotomy (by classic preauricular incision) after arthroscopy was necessary in one patient (case 5) in order to completely remove loose bodies, due to their abundance.

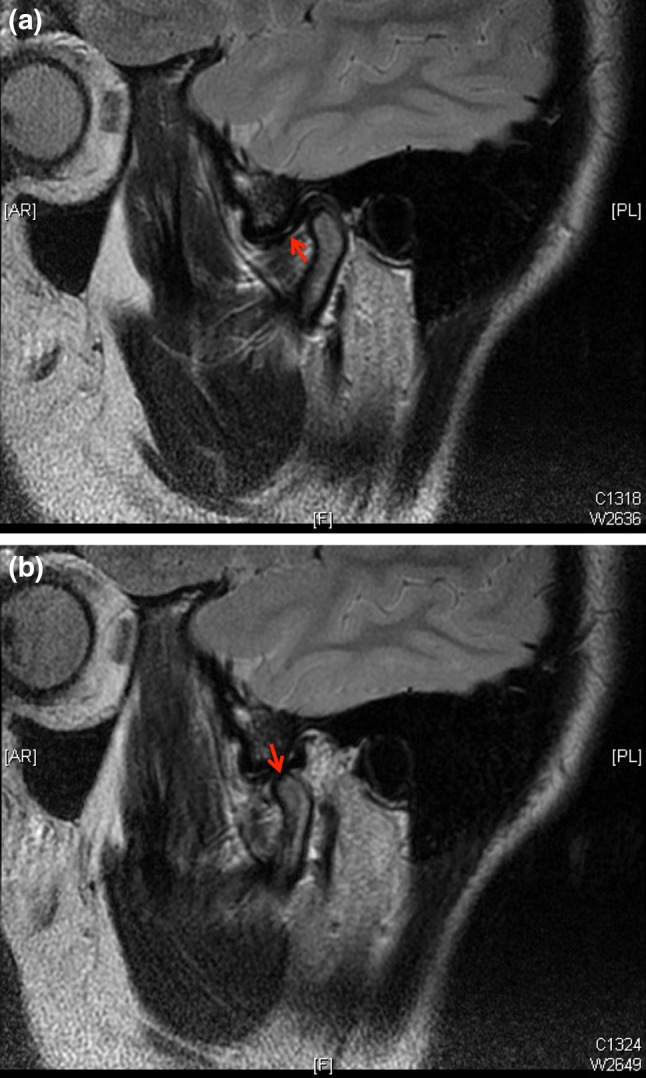

During the follow-up period, pain improved significantly in the cases that presented significant pain (cases 3 and 4). MMO after surgery was normal in three cases. The average pain observed at 3, 6 and 12 months post-operatively were 6 mm (SD ± 6.5), 6.6 mm (SD ± 5.1) and 3 mm (SD ± 4.4), respectively. The average MMO observed at 3, 6 and 12 months post-operatively was 35.2 mm (SD ± 13.4), 38.8 mm (SD ± 12.1) and 43 mm (SD ± 11.2), respectively. None of the patients showed signs of relapse during the follow-up period. A follow-up MRI was taken in 4 out of the 6 patients. Two of the patients showed disc displacement, but none of them showed signs of chondromatosis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Follow-up T2-weighted magnetic resonance image in FSE sequence 1 year after surgery showing a normal joint, with no signs of synovial effusion or synovial chondromatosis. Articular disc is marked with red arrows in a (mouth closed) and in b (mouth open)

A review of the literature revealed a total of 10 articles [5, 15–23] published between 2007 and 2017, with a total of 79 cases (59 female and 20 male patients) (Table 3). The average age at diagnosis was 44.8 years (range 21–74 yrs). The left joint was affected in 39 cases and the right joint in 40 cases. Treatment exclusively with arthroscopy was used in 38 patients (48.1%), and arthroscopy-assisted open surgery was used in 41 patients. A summary of the literature review analysis is given in Table 4.

Table 3.

Systemic review of patients diagnosed with TMJ synovial chondromatosis and treated with open arthrotomy or arthroscopy

| References | Year of publication | Journal | Number of cases | Age (mean) | Gender (F/M) | Joint (R/L) | Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [16] | 2007 | Dentomaxillofac Radiol | 1 | 32 | F | R | Open plus arthroscopy (arthroscopy first) |

| 2 | [5] | 2008 | J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 3 | 37–56 (46) | 2/1 | 2 R, 1L | Arthroscopy |

| 3 | [17] | 2008 | Dentomaxillofac Radiol | 1 | 35 | F | R | Arthroscopy |

| 4 | [18] | 2008 | Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 1 | 28 | F | R | Open plus arthroscopy (arthroscopy first) |

| 5 | [19] | 2010 | Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 1 | 74 | F | L | Open plus arthroscopy |

| 6 | [20] | 2010 | Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod | 1 | 44 | F | R | Arthroscopy |

| 7 | [21] | 2011 | J Craniomaxillofac Surg | 1 | 50 | M | L | Arthroscopy |

| 8 | [15] | 2012 | J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 33 | 21–62 (43) | 26/7 | 18 R, 15 L | 32 arthroscopy, 1 + open |

| 9 | [22] | 2013 | Dentomaxillofac Radiol | 1 | 34 | F | R | Open plus arthroscopy (arthroscopy first) |

| 10 | [23] | 2017 | Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg | 36 | 29–65 (48.1) | 25/11 | 14 R, 22 L | Open plus arthroscopy |

Table 4.

Summary of systematic review

| Total number of cases (F/M) | 79 (59/20) |

|---|---|

| Number articles (2007–2017) | 10 |

| Average age (range) | 44.8 yrs (21–74) |

| Side affected | |

| Left joint | 39 |

| Right joint | 40 |

| Surgical options | |

| Arthroscopy | 38 |

| Open + arthroscopy | 41 |

Discussion

Internal derangement is the most common temporomandibular joint disorder, with degenerative osteoarthritis and trauma being other frequent pathologies. Synovial chondromatosis (SC), or synovial chondrometaplasia, of the TMJ is a rare condition, but is the most common neoplastic lesion of this joint [1, 2]. SC has an unspecific clinical presentation that in many cases mimics an internal derangement, since the main clinical characteristics are similar to the ones of internal derangement: pain, swelling and joint dysfunction [24]. Patients receive conservative treatment for this condition and the final diagnosis of SC could be delayed until an invasive diagnostic and/or therapeutic method is indicated [5], which is why arthroscopy frequently discovers a TMJ SC.

However, the development of new imaging modalities such as TMJ-specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan has allowed for early and specific diagnosis of this entity [8, 10, 14, 15]. CT images can identify soft tissue swelling, define the size, shape and location of loose bodies or show possible changes in the articular surface of the temporal bone in addition to extra-articular extension [10]. An MRI can also identify loose bodies in the articular space as well as effusion in the superior and/or inferior articular space and bone erosion [1, 15]. Disc position definition and concomitant TMJ derangement can also be diagnosed by MRI [14]. The MRI is not only useful for the diagnosis of the patient, but it is also useful for follow-up after surgery, which we used in four of our patients, showing no signs of relapse.

In SC, the most frequent arthroscopic findings are loose bodies in the superior joint space (less frequently in the inferior space), synovitis with areas of metaplasia and proliferation and variable grades of chondromalacia. These findings often appear together with signs of disc pathology, such as disc displacement, synovitis of the posterior ligament or disc perforation (cases of secondary SC). Loose bodies can be removed with a forceps inserted in the articular space through a cannula or even by a wider third cannula [5]. Arthroscopy can also show areas of synovitis, which can be coagulated with bipolar or radiofrequency devices; synovial biopsies can also be performed.

The results observed in our series of patients treated by arthroscopy were very good. Pain was the main symptom in our patients, which improved significantly after arthroscopic treatment. The average pain changed from 46.7 mm on a VAS preoperatively to 3 mm 12 months after surgery. This improvement was also stable throughout follow-up. The maximum mouth opening also improved post-operatively, although the patients were not functionally affected initially. The average MMO changed from 32.3 mm preoperatively to 43 mm 12 months after surgery.

Several authors still recommend open surgery for treating SC [1]. However, Fernandez-Sanroman et al. [5] demonstrated in a series of five patients that arthroscopy is the surgical option of choice in SC limited to TMJ space. Cai et al. [15] also demonstrated good results with arthroscopy in a large series of 33 patients (the largest series in medical literature) with SC when it was confined to the joint space. Other authors had also previously described the arthroscopic use in SC [7, 13]. Bai et al. [23] argue that there are dead zones such as the medial groove of the joint capsule that cannot be reached by open surgery. In these cases, they recommend the use of arthroscopy to complete treatment after open surgery. They found the presence of loose bodies in the anterior or posterior recesses in 14 patients that would not have been removed if only open surgery was done. In these patients, arthroscopy was not done from the start due to the size of some of the loose bodies. We also advocate for arthroscopic management in cases of intraarticular SC, especially in cases of associated internal derangement as it also allows for repositioning and preservation of the disc.

Open surgery is the treatment of choice in SC with extra-articular extension and in SC recurrences [5]. Extra-articular extension may occur with affectation of the middle cranial fossa, the infratemporal space or the parotid region [3–5]. Affectation of the cranial fossa can produce neurological symptoms as headaches, sensory or motor defects or decreased acoustic sensibility [3]. When extra-articular SC occurs, open arthrotomy is performed by a preauricular approach [4], with removal of loose bodies and synovectomy, and a careful resection of the entire expansive lesion. A parotidectomy may be necessary if the lesion affects the gland. Involvement of the inferior joint space is extremely rare and it could even affect the condyle. In this situation, a high condylectomy may be necessary [9].

Recurrence is extremely rare in SC, but is more frequent in primary SC and in cases of extra-articular extension with incomplete resection of the lesion [1, 13]. There were no signs of clinical or radiological recurrence during follow-up in the six cases treated by TMJ arthroscopy, a minimally invasive procedure with no post-operative complications.

In conclusion, TMJ SC can be mistaken for an internal derangement or it can also appear associated with disc displacement, so a correct diagnosis is fundamental. Arthroscopic management is an excellent option for a complete diagnosis and treatment of intraarticular SC, with no severe post-operative complications, a subsequent clinical improvement and no clinical or radiological recurrence of the disease. Open arthrotomy should only be reserved for cases of extra-articular SC or the presence of loose bodies measuring more than 3 mm.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study

References

- 1.Ardekian L, Faquin W, Troulis MJ, Kaban LB, August M. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: report and analysis of eleven cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:941–947. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koyama J, Ito J, Hayashi T, Kobayashi F. Synovial chondromatosis in the temporomandibular joint complicated by displacement and calcification of the articular disc: report of two cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1203–1206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu MH, Ma XC, Guo CB, Yi B, Bao SD. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with middle cranial fossa extension. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gil-Salu JL, Lazaro R, Aldasoro J, Gonzalez-Darder JM. Giant solitary synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint with intracranial extension. Skull Base Surg. 1998;8:99–104. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1058583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez-Sanroman J, Costas-Lopez A, Badiola IA, Fernandez-Ferro M, Lopez de Sanchez A. Indications of arthroscopy in the treatment of synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: report of 5 new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1694–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petito AR, Bennett J, Assael LA, Carlotti AE. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: varying presentation in 4 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:758–764. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.107533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendoza-Caridad JJ, Schwartz HC. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:624–625. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyamoto H, Sakashiya H, Wilson DF, Goss AN. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38:205–208. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1999.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Lindern JJ, Theuerkauf I, Nierderhagen B, Berge S, Appel T, Reich RH. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: clinical, diagnostic and histomorphologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:31–38. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.123498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu Q, Yang J, Wang P, Shi H, Luo J. Ct features of synovial chondromatosis in the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:524–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmlund AB, Eriksson L, Reinholt FP. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. Clinical, surgical and histological aspects. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:143–147. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milgram JW. Synovial chondromatosis: a histopathologic study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg. 1977;59:792–801. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197759060-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyamoto H, Sakashita H, Miyata M. Kurita kK. Arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular joint synovial chondromatosis: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:629–631. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(96)90648-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin-Granizo R, Sanchez JJ, Jorquera M, Ortega L. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: a clinical, radiological and histological study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai XY, Yang C, Chen MJ, Jiang B, Zhou Q, Jin JM, Yu B, Chen ZZ. Arthroscopic management for synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: a retrospective review of 33 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:2106–2113. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li B, Long X, Cheng Y, Yang X, Li X, Cai H. Ultrasonographic and arthrographic diagnoses of synovial chondromatosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2007;36:175–179. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/32238405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honda K, Hamada Y, Ejima K, Tsukimura N, Kino K. Interventional radiology of synovial chondromatosis in the temporomandibular joint using a thin arthroscope. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37:232–235. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/24806371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sembronio S, Albiero AM, Toro C, Robiony M, et al. Arthroscopy with open surgery for treatment of synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:582–584. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato J, Notani KI, Goto J, Shindoh M, Kitagawa Y. Synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint accompanied by loose bodies in both the superior and inferior joint compartments: case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:86–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng J, Guo C, Yi B, Zhao Y, et al. Clinical and radiologic findings of synovial Chondromatosis affecting the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen MJ, Yang C, Zhang XH, Qiu YT. Synovial chondromatosis originally arising in the lower compartment of temporomandibular joint: a case report and literature review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;39:459–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto K, Sato T, Iwanari S, Kameoka S, Oki H, Komiyama K, et al. The use of arthrography in the diagnosis of temporomandibular joint synovial chondromatosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2013;42(1):15388284. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/15388284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai G, Yang C, Qiu Y, Chen M. Open surgery assisted with arthroscopy to treat synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Huang Z, Wangyong Zhu W, Liang P, Tao O. Clinical and Imaging Findings of Temporomandibular Joint Synovial Chondromatosis: an Analysis of 10 Cases and Literature Review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:2159–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]