Abstract

Aim

To compare the analgesic efficacy of Diclofenac vis-a-vis Ketoprofen transdermal patch, in the management of immediate post-operative pain following orthognathic procedures.

Material and Method

A prospective, double-blinded, randomised controlled study was conducted among 50 subjects, between 2012 and 2015. These patients were diagnosed clinically and cephalometrically as skeletal and dental class II malocclusion and underwent bi-jaw surgical procedure. In total, 25 Diclofenac and 25 Ketoprofen transdermal patches, sealed in envelopes and numbered, were administered to subjects. The patches used, contained 100 mg of either Diclofenac or Ketoprofen and administered by a nurse prior to induction. Duration of analgesia, severity of pain using Visual Analog Scale, necessity of rescue analgesia (spontaneous pain > 5 on a 10-cm scale) and any other adverse effect associated with the drug were evaluated.

Results

Mean duration of analgesia was significantly higher in the Ketoprofen group (20 h), compared to Diclofenac group (13 h) (p = 0.001). Rescue analgesia was required in 12% of subjects who received Diclofenac patch, compared to 4% in Ketoprofen group. None of the subjects showed any allergic reactions.

Conclusion

The study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of transdermal patch in reduction of post-operative pain in subjects undergoing bi-jaw surgeries. Subjects in both groups were comfortable and returned to early function. However, Ketoprofen transdermal patch had an edge over the Diclofenac transdermal patch with respect to analgesic efficacy.

Keywords: Transdermal patch, Bi-jaw surgery, Immediate post-operative pain, Duration of analgesia

Introduction

Injured tissue releases pain-modulating factors also known as prostaglandins. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) reduce the prostaglandin production by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase, thereby achieving analgesia [1]. They can be administered via gel, ointment, cream, paste, oral, parenteral or transdermal route. The oral route is most commonly used but is associated with certain adverse effects like gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcers, hypertension, oedema and renal disease. A medicated adhesive placed on the skin to deliver a sustained release of the drug through the cutaneous route into the bloodstream is known as a skin patch or transdermal delivery system (TDDS) [1].

These drugs when applied topically in the form of a transdermal patch penetrate the skin, subcutaneous fatty tissue, muscle and finally into the blood stream in amounts sufficient to exert therapeutic effects without reaching higher plasma drug concentrations as in the case of parenteral or intramuscular administration. They have the added advantage of avoiding first-pass metabolism as well as reducing the systemic toxicity [2, 3].

Based on this information, we intended to evaluate the comparative analgesic efficacy and side effects of non-invasive drug delivery system using Diclofenac and Ketoprofen in the management of immediate post-operative pain following orthognathic surgery. Active ingredient used for comparison were Diclofenac and Ketoprofen. The hypothesis was that TDDS old reduces requirement of analgesics in immediate post-operative phase.

Materials and Methods

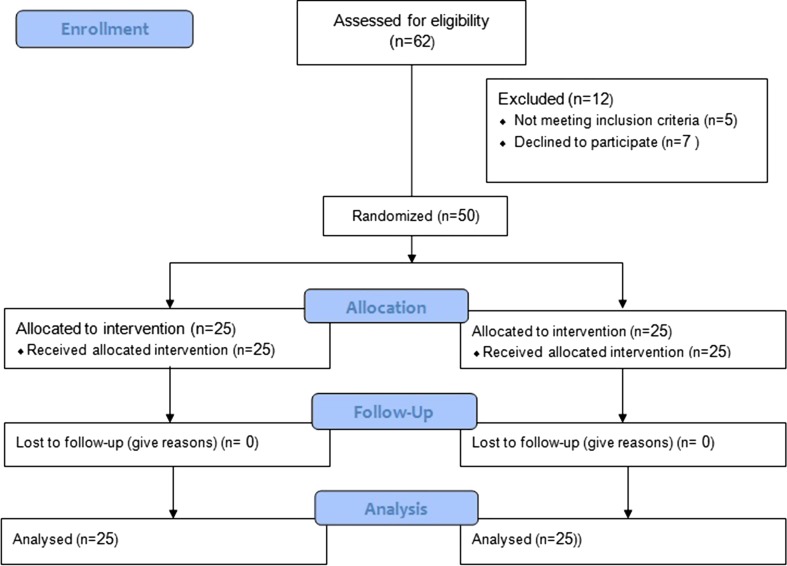

A prospective, double-blinded, concurrent, parallel, randomised controlled trial with an allocation ratio 1:1 was conducted in department of oral and maxillofacial surgery between 2012 and 2015. The study intended to compare the analgesic efficacy of Diclofenac and Ketoprofen TDDS patch in the management of immediate post-operative pain.

A total of 50 subjects in the age group 18–26 years, undergoing bi-jaw surgery for the correction of dentofacial deformities, were included in the study. Subjects with any associated history of bleeding disorder, allergy to NSAIDs, bronchial asthma, peptic ulcers, history of liver or kidney disease, abuse of drugs and alcohol were excluded from the study. The study was approved by institutional ethics committee, and patients were given detailed information about study, following which written informed consent was taken. 25 Diclofenac (100 mg SANDOR DICLO-TOUCH, Control group) and 25 Ketoprofen (100 mg SANDOR ARTHO-TOUCH, Test group) (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Diclofenac patch

Fig. 2.

Ketoprofen patch

A matrix type patch was used, which is simple in design, and skin permeability governs the drug delivery. Drug penetrates to capillary loops of dermis, reaching systemic circulation, thus providing a painless route of administration and hence improving patient compliance [4]. A relatively less hairy region for proper adaption of matrix patch was selected (Fig. 3). All subjects received TDDS just before anaesthetic induction. Standard protocols were followed, with due attention being paid to ensure consistency with anaesthetic drugs.

Fig. 3.

Transdermal patch in deltoid region

Anaesthetic regimen included premedication (injection glycopyrrolate, midazolam, nalbuphine, ondansetron, pantocid and Diclofenac or Ketoprofen TDDS patch) induction (propofol), during intubation (succinylcholine), maintenance (nitrous oxide 50%, sevoflurane and vecuronium bromide) and reversal (neostigmine and glycopyrrolate). None of the subjects were given analgesics in the immediate post-operative phase.

In the immediate post-operative phase, intensity of pain was recorded using VAS of 10 cm, in all the subjects at the time of application of patch and at periods of 2, 6, 12, 24 h. Whenever VAS score was greater than 5, injection tramadol 2 mg/kg was administered intramuscularly as rescue analgesia. The time of rescue analgesia was recorded.

Taking these factors into consideration, a pilot study was conducted in 6 individuals (3 each for Diclofenac patch and Ketoprofen patch), neither randomised nor blinded. Reduced analgesic requirement in all subjects was observed. From the results of the pilot study, taking the mean duration of analgesia into consideration and setting the power of the sample to be 80%, the final sample size was estimated to be 25 in each group.

A nurse not associated with the study placed medicated patches into envelopes, numbered them from 1 to 50 and maintained a record of type of patch present in each envelop (1–50 envelopes). This was done to ensure that the subjects as well as the investigator were unaware of the drug administered to each patient. In total, 100 mg Ketoprofen maintains a plasma concentration lower than oral administration, thereby reducing systemic toxicity [5]. Therefore, 100 mg of Diclofenac and Ketoprofen was chosen for evaluation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Parameters

| S. no. | Group A | Group B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 26.86 | 26.60 | 0.833 NS |

| Sex | 18 Females 7 Males |

20 Females 5 Males |

0.383 NS |

| Duration of surgery | 226.80 | 227.0 | 0.732 NS |

| Duration of analgesia | 814.6 | 1204.2 | <0.001 S |

| Rescue analgesia | 03 | 01 | NS |

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 20.0. Student’s t test was used for analysis of continuous data (age, duration of analgesia, VAS score), and Chi-square test was used for categorical data (gender, need for rescue analgesia).

Results

Among 50 subjects enrolled in the study, 25 were allocated to group A (Diclofenac) and 25 were allocated to group B (Ketoprofen). Both groups had comparable demographic characters (18 females and 7 males in group A and 20 females and 5 males in group B). The mean age of the individuals in group A and group B was 24.86 years and 23.60 years, respectively (p = 0.833).

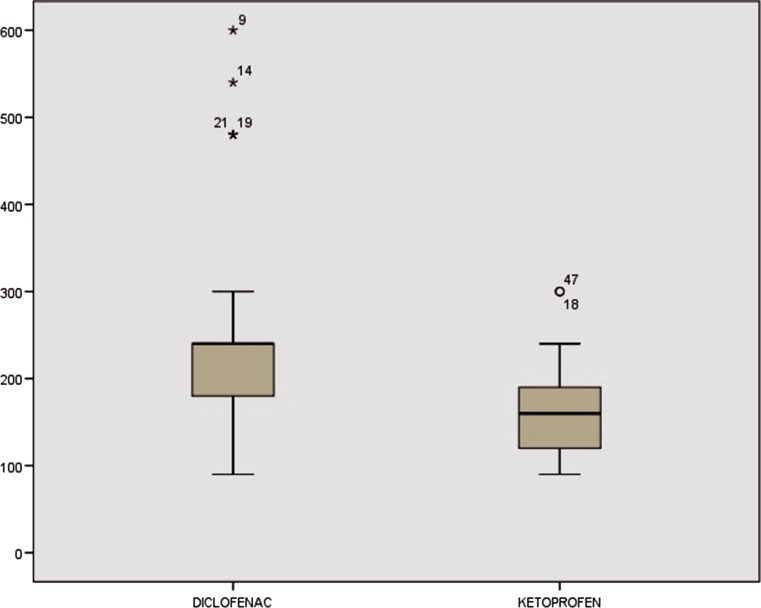

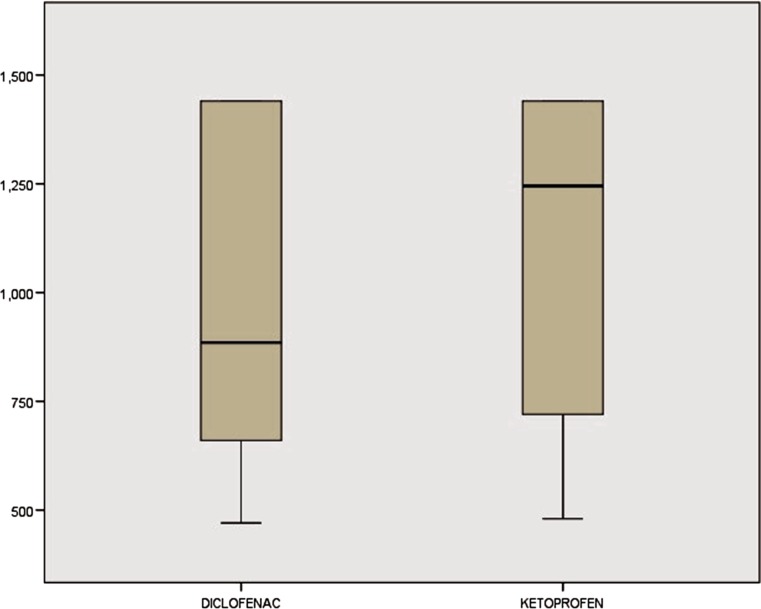

The mean duration of surgery (DOS) was measured from point of induction to point of extubation. DOS was 227.00 and 226.80 min in Diclofenac and Ketoprofen group, respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.732) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Duration of surgery in minutes

Duration of analgesia (DOA) was measured from time of patch application to time where subject complained of pain > 5 on a 10-cm VAS. The mean DOA in group A was 814.6 min (13 h) compared to 1204.2 min (20 h) in group B, and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.001) as shown in Fig. 5. Rescue analgesia was given in 12 and 04% of subjects in group A and group B, respectively. Hemodynamics were stable in both the groups perioperatively. None of the patients in either group developed post-operative nausea, vomiting, head ache, allergy or skin rash.

Fig. 5.

Duration of analgesia in minutes

Discussion

Surgical correction of dentofacial deformities involves extensive manipulation of hard and soft tissues. Excessive tissue handling increases the release of inflammatory mediators, thereby increasing the possibility of post-operative pain. The efficacy of NSAIDs in reducing the post-operative pain depends on the ability to inhibit cyclooxygenases which are key in prostaglandin synthesis [6]. Diclofenac is arachidonic acid derivative, while Ketoprofen is a propionic acid derivative, and both of them act by non-selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase pathway. Ketoprofen has proved its efficacy in terms of prolonged analgesia in various modes of administration such as intramuscular and oral route over opioids, Diclofenac and ibuprofen in orthopaedic and rheumatic pain [7–9]. TDDS bypasses first-pass metabolism in the liver and overcomes concerns regarding drugs that are poorly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract [10]. This facilitates the use of a sustained released analgesic in a non-invasive form to enhance the comfort levels of the patient (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Consort

Placebo-controlled studies have shown 100 mg Ketoprofen to be effect in pain reduction in treatment of ankle sprain [5]. Use of Diclofenac patches in sports injuries has also shown statistically significant difference in pain relief over a period of 2 weeks in placebo-controlled studies [11]. Ketoprofen in TDDS has been shown to be better absorbed than Diclofenac, which can be attributed to the difference in their molecular weights, i.e. 260 and 325 Da, respectively [12]. TDDS patch provides sustained release of Ketoprofen over 24 h, ensuring better compliance, compared to cream, gel and spray, which often require multiple applications every day [13].

In the study, DOS was measured from start of induction to extubation. All subjects underwent bi-jaw surgery by the same experienced surgeon, so amount of hard and soft tissue manipulation was the same, and DOS was 227.00 and 226.80 min in group A and group B, respectively, which was not significant (p = 0.732).

The DOA measured using VAS score on a 10-cm scale, from the time of patch application and at the end of 2, 6, 12, 24 h. The mean DOA was 13 and 20 h in Diclofenac and Ketoprofen groups, respectively (p = 0.001), which was statistically significant. This difference in duration of analgesia may be attributed to the fact that Ketoprofen has a central component inhibiting the spinal cord nociceptor reflex activity and reducing the central sensitisation in the cord. This central activity achieves an analgesic effect similar to opioids while avoiding the risk of respiratory depression. It is therefore indicated in musculoskeletal and joint disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, periarticular disease [7, 14].

In the present study 12% of subjects in the Diclofenac group required rescue analgesic in the form of tramadol given parentally compared to 4% in Ketoprofen group. Tramadol being an opioid and possessing a higher analgesic efficacy was advocated for reliving pain in these patients.

There was no difference in hemodynamic changes after application of the patch in either group. Blood pressure values were at 110 ± 8 systolic and 84 ± 6 diastolic. These findings are in accordance with previously studies which evaluated parenteral Diclofenac and Ketoprofen [7, 15–17]. Respiratory rate ranged from 14 to 18 cycles per minute, and pulse ranged from 60 to 80 beats per minute when compared to baseline.

Application of a transdermal patch may be associated with itching, rash, erythema or allergic reaction at the anatomical site of application. None of the subjects in the study showed these manifestations. General complication such as nausea and vomiting which may be encountered as stated by Kostamovaara [16] was not encountered in our study.

NSAIDs can cause reversible impairment of glomerular filtration, acute renal failure, oedema, interstitial nephritis, papillary necrosis, chronic renal failure and hyperkalaemia [18]. Use of a minimum adequate dosage of analgesic in the form of transdermal patch minimises systemic complications [19] as seen in the present study. TDDS is comfortable, acceptable and easily available at reasonable cost.

The duration of analgesia—the evaluation factor—was comparatively high for Ketoprofen TDDS patch. This is the first study of its kind performed on subjects with dentofacial deformities undergoing bi-jaw surgery, evaluating the efficacy of Diclofenac and Ketoprofen transdermal patches, which are easily available, easy to administer and long acting.

Conclusion

Individuals undergoing elective surgical procedures are more demanding in terms of surgical procedure, surgical outcome and post-operative pain management. Use of transdermal patch bypasses first-pass metabolism, avoids needle pricks and reduces systemic toxicity with sustained release of the drug in a non-invasive way. Both Ketoprofen and Diclofenac TDDS patch provided good analgesia in the immediate post-operative phase. However, analgesic efficacy of Ketoprofen was found to be significantly better than Diclofenac.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Anisha and Dr. Sasank for their general support and assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Ng P, Kam CW, Yau HH. A comparison of Ketoprofen and Diclofenac for acute musculoskeletal pain relief: a prospective randomised clinical trial. Hong Kong. J Emerg Med. 2001;8:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhiman S, Gurjeet TS, Rehni AK. Transdermal patch: a recent approach to the new drug delivery system. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2011;3(5):26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar SV, Tarun P, Kumar TA. Transdermal drug delivery system for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a review indo American . J Pharm Res. 2013;3(5):3588–3605. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prausnitz MR, Mitragotri S, Langer R. Current status and future potential of transdermal drug delivery. Nat Rev. 2004;3:115–124. doi: 10.1038/nrd1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazières B, Rouanet S, Velicy J, Scarsi C, Reiner V. Topical Ketoprofen patch (100 mg) for the treatment of ankle sprain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:515–523. doi: 10.1177/0363546504268135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyneman CA, Lawless- Liday C, Wall GC. Oral vs topical NSAIDS in rheumatic diseases: a comparison. Drugs. 2000;60(3):555–574. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prabhakar H, Shrirao SA, Shelgaonkar VC, Ghosh AA. Comparative evaluation of intramuscular Ketoprofen and Diclofenac sodium for postoperative pain relief. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2005;11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna MH, Elliott KM, Stuart-Taylor ME. Comparative study of analgesic efficacy and morphine sparing effect of intramuscular dexketoprofen trometamol with Ketoprofen or placebo after major orthopaedic surgery. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(2):126–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atzeni F, SarziPuttini P, Lanata L, Bagnasco M. Efficacy of Ketoprofen vs ibuprofen and Diclofenac: a systematic review of the literature and meta analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;31(5):731–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishna R, Nataraj MS. Efficacy of a single dose of a transdermal Diclofenac patch as pre-emptive postoperative analgesia: a comparison with intramuscular Diclofenac. S Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2012;18(4):194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elhakim M. A comparison of intravenous Ketoprofen with pethidine for postoperative pain relief following nasal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1991;35:279–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1991.tb03289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adachi H, Ioppolo F, Paloni M, Santilli V. Physical characteristics, pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy of the Ketoprofen patch: a new patch formulation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15:823–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie LD. A clinical evaluation of flurbiprofen LAT and piroxicam gel: a multicentre study in general practice. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF02229701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanida N, Sakurada S. Skin permeability, anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of Ketoprofen-containing tape and loxoprofen sodium containing tape. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2008;36:1123–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galer BS, Rowbotham M, Perander J. Topical Diclofenac patch relieves minor sports injury pain: results of a multicenter controlled clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:287–294. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kostamovaara PA, Hendolin H, Kokki H. Ketorolac, Diclofenac and Ketoprofen are equally efficacious for pain relief after total hip replacement surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:369–372. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rorarius MGE, Suominen P, Baer GA. Diclofenac and Ketoprofen for pain treatment after elective caesarean section. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:293–297. doi: 10.1093/bja/70.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooks PM, Day RO. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs-differences and similarities. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1716–1725. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perttunen K, Kalso E, Heinonen J, Salo J. IV Diclofenac in post thoracotomy pain. Br J Anaesth. 1992;68:474–480. doi: 10.1093/bja/68.5.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]