Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a tumor that usually metastasizes to lung, liver, bone and brain, but rarely to skeletal muscles. We report a case of an elderly man with a history of bilateral metachronous RCC for which he underwent curative bilateral nephrectomies and renal transplantation, was in remission, and presented with a large solitary skeletal muscle metastasis from the initial RCC, 3 years later.

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, Skeletal muscle metastasis

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma is the most common cancer of the kidney and accounts for about 3% of all adult malignancies in the United States [1]. Its incidence in our country is relatively high, reaching 4.3 cases per 100,000 population in men and 1.7 cases per 100,000 population in women [2]. It is known to metastasize to lung, liver, bone and brain, but very rarely to skeletal muscles. Surov et al. [3] found that 2.3% of patients with RCC develop, or are found at presentation, to have skeletal muscle metastasis.

We report a case of solitary metastatic RCC deposited into a skeletal muscle, which occurred 3 years after curative nephrectomy, with review of literature.

Case report

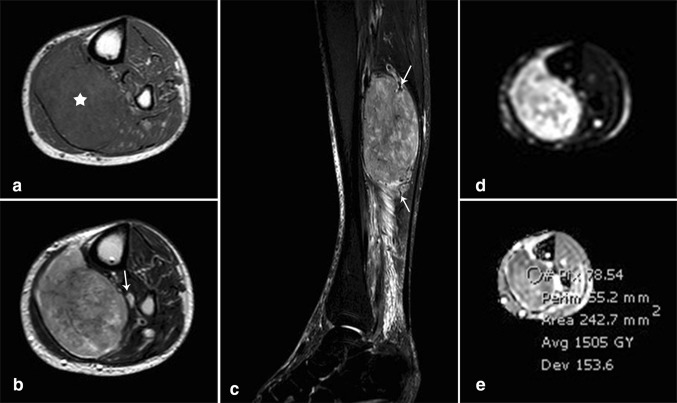

The patient is a 74-year-old man, known to have hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation with prior left pelvic renal transplantation for renal failure. Post transplantation, the patient was maintained on daily cyclosporine, 100 mg orally in the morning and 75 mg orally in the evening, and prednisone 5 mg orally once daily. Thirteen years later, he presented with painless hematuria of 5 months duration and was found to have a renal mass on ultrasound and CT scan located at the upper pole of the left native kidney for which left nephrectomy was performed and revealed renal cell carcinoma on tissue diagnosis. One year later, right native nephrectomy was done after detecting another renal mass at the lower pole of the right kidney during regular CT follow-up. No chemotherapy was administered after both nephrectomies, since both metachronous renal cell carcinoma were localized. Three years later the patient presented with a large palpable posterior left leg mass. Ultrasound showed a 10.6 × 3.9 × 5.7 cm, slightly heterogeneous, hypoechoic mass in the posterolateral aspect of the left calf, located within the medial aspect of the soleus muscle (Fig. 1a). It showed increased vascularity on power Doppler examination (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Grayscale ultrasound image of the left calf (a) showing large lobulated slightly heterogeneous soft tissue mass. Power Doppler exam (b) revealed significant increased flow within the tumor

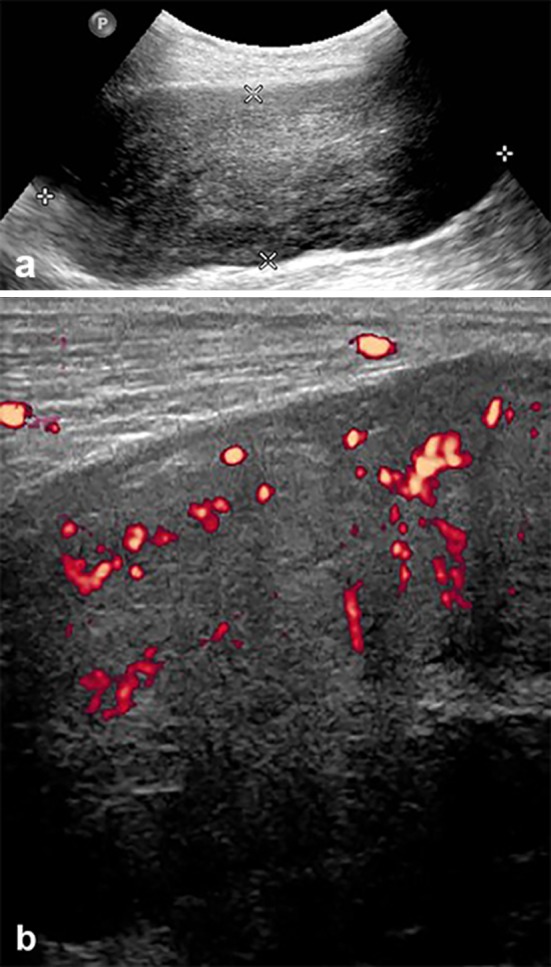

MR imaging (Fig. 2) of the left leg was then performed on 1.5 T magnet (Philips Ingenia, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) and showed a large 12 × 7.3 × 5.8 cm soft tissue lesion within the soleus muscle which had isointense signal on T1-weighted images (Fig. 2a) and appeared heterogeneous on T2-weighted images showing variable signals (Fig. 2b). The mass was compressing the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle and displacing it anteriorly. Sagittal STIR images (Fig. 2c) showed similar signal to that seen on T2-weighted images along with peripheral prominent flow voids. The lesion showed areas of high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted images (Fig. 2d) and low signal intensity on ADC map (Fig. 2e) consistent with impeded diffusion. The mean ADC value was 1.5 and the minimum ADC value was 1.1. Intravenous gadolinium was not administered due to the patient’s kidney status.

Fig. 2.

MR imaging. (a) Axial T1-weighted (TR/TE = 532/20): large tumor (star) involving the soleus muscle at the proximal posterior leg compartment. The tumor is relatively isointense to the surrounding muscles. (b) Axial T2-weighted (TR/TE = 1205/100): heterogeneous tumor with areas of low, intermediate and high signal intensity. The tumor is abutting the posterior tibial neurovascular bundle (arrow). (c) Sagittal short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) (TR/TE = 7380/60): The tumor shows signal intensity similar to that seen on T2-weighted sequence. Multiple flow voids are noted at the periphery of the tumor corresponding to prominent vascularity (arrows). Note the presence of reactive edema in the surrounding muscle fascicles and deep fat planes, distally. (d, e) Axial diffusion-weighted images (d) (b = 900) and corresponding ADC map (e) showing heterogeneous SI of the tumor with mild restriction, mean ADC = 1.5 (range for malignancy: 0.7–1.2)

Ultrasound-guided biopsy was then performed and the pathology specimen showed evidence of tumors cells with positive staining on vimentin and cytokeratin markers, consistent with metastasis from renal cell carcinoma (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Histopathology slides obtained from a percutaneous core biopsy. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×40: sheets of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm are present. The nuclei are variably sized with occasional prominent nucleoli (arrows). (b) Positive staining with mesenchymal marker (vimentin, ×40). (c) Positive staining with epithelial marker (cytokeratin, ×40)

The patient later underwent a wide resection of the tumor with negative margins on pathology and had preserved function of his lower limb. No further treatment was provided.

Discussion

Muscle metastasis from solid tumors is rare. Lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, gastrointestinal tumors and genital tumors were the most commonly reported primary malignancies metastasizing to the skeletal muscles [4].

Renal cell carcinoma rarely metastasizes to skeletal muscle, seen in approximately 2.3% of cases [3]. Less than 100 cases have been reported in the literature. Damron et al. [5] reported that RCC metastases in soft tissues, including skeletal muscle, almost always present as a solitary mass after a variable period of time from the initial diagnosis of RCC. This makes the differentiation between this unusual skeletal metastasis and primary skeletal muscle tumor challenging. The different imaging modalities are not enough to make this distinction and eventually a tissue biopsy is needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

A painful mass is the most common presenting symptom of skeletal muscle metastasis. Primary soft tissue sarcoma typically presents as painless soft tissue mass, making pain a symptom highly suggestive of metastasis rather than primary soft tissue tumor [5].

Surov et al. [6] studied the radiological appearance of muscle metastasis in a large series of 461 patients having variable primary tumors. The authors found five different CT patterns of muscle metastasis. Approximately half of the cases (46.5%) presented as round or oval masses with homogeneous contrast enhancement (type I). In this series, 38 patients with metastatic RCC were included and most of them show type I lesions. In the same series, MRI showed on T1W images 48.3% of these muscle metastases to be homogeneously isointense compared with unaffected muscle tissue. On T2W images, 81.6% of the metastases were hyperintense when compared to normal muscle. In our case, the mass had the same signal characteristics on T1-weighted, but is heterogeneous on T2-weighted images.

After intravenous administration of contrast medium, most lesions (87.2%) showed a heterogeneous enhancement.

On ultrasound, 97.5% were hypoechoic, as seen in our patient.

On PET/CT, muscle metastasis manifested as focal hypermetabolic lesion [6].

Magnetic resonance imaging findings of skeletal muscle metastasis from renal cell carcinoma with diffusion sequence have rarely been described in the literature. Pirimoglu et al. [7] described in their case report the characteristics of multiple muscle metastases on magnetic resonance imaging in a man with renal cell carcinoma 4 years after right radical nephrectomy. These lesions had similar appearance to our presented case, except on T1-weighted images, where Pirimoglu et al. [7] reported low signal intensity.

The immunosuppressed status of our patient, related to cyclosporine and prednisone treatment for 13 years, might have played a major role in the development of bilateral metachronous renal cell carcinoma. In fact, Tremblay et al. [8] reported a high incidence of skin and genitourinary cancers in patients who developed malignancies following renal transplantation, and this, since the introduction of cyclosporine as part of new immunosuppression regimens. Agraharkar et al. [9] also reported a higher risk of malignancy in 1739 renal transplant patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs and observed a sevenfold increase in risk for RCC compared to the general population. In both studies, skeletal muscle metastases from RCC were not discussed.

On the other hand, Lim et al. [10] showed decreased risk of cancer in renal transplant patients receiving everolimus instead of cyclosporine, in particular the non-melanoma skin cancer. This emphasizes the need to consider switching from calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine) to sirolimus (everolimus) in this patient population, which might have benefited our patient.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of bilateral renal cell carcinoma with metastasis to skeletal muscle 3 years after curative nephrectomies. We describe the ultrasound and MR findings with histopathologic correlation and literature review. Late onset skeletal metastases should be always considered in patients with RCC, even after cure. We also discussed the development of RCC in relation with the immunosuppressed status of our patient, especially with the use of cyclosporine.

Conflict of interest

All the authors have declared no competing interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Rida Salman, Email: rs160@aub.edu.lb.

Mikhael G. Sebaaly, Email: ms246@aub.edu.lb

Karl Asmar, Email: ka73@aub.edu.lb.

Mohammad Nasserdine, Email: mn103@aub.edu.lb.

Sami Bannoura, Email: sb92@aub.edu.lb.

Nabil J. Khoury, Email: nk01@aub.edu.lb

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(2):106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosn M, Jaloudi M, Larbaoui B. Insights into the epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma in North Africa and the Middle East. Pan Arab J Oncol. 2005;8(2):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surov A, Hainz M, Holzhausen HJ, Arnold D, Katzer M, Schmidt J, et al. Skeletal muscle metastases: primary tumours, prevalence, and radiological features. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(3):649–658. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molina-Garrido MJ, Guillen-Ponce C. Muscle metastasis of carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13(2):98–101. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damron TA, Heiner J. Distant soft tissue metastases: a series of 30 new patients and 91 cases from the literature. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(7):526–534. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surov A, Köhler J, Wienke A, Gufler H, Bach AG, Schramm D, et al. Muscle metastases: comparison of features in different primary tumours. Cancer Imaging. 2014;14(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1470-7330-14-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirimoglu B, Ogul H, Kisaoglu A, Karaca L, Okur A, Kantarci M. Multiple muscle metastases of the renal cell carcinoma after radical nephrectomy. Int Surg. 2015;100(4):761–764. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00197.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tremblay F, Fernandes M, Habbab F, de Edwardes MDB, Loertscher R, Meterissian S. Malignancy after renal transplantation: incidence and role of type of immunosuppression. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(8):785–788. doi: 10.1007/BF02574501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agraharkar ML, Cinclair RD, Kuo YF, Daller JA, Shahinian VB. Risk of malignancy with long-term immunosuppression in renal transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2004;66(1):383–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim WH, Russ GR, Wong G, Pilmore H, Kanellis J, Chadban SJ. The risk of cancer in kidney transplant recipients may be reduced in those maintained on everolimus and reduced cyclosporine. Kidney Int. 2017;91(4):954–963. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]