Abstract

Refractory pleural effusion can be a life-threatening complication in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. We report successful treatment of refractory pleural effusion using a Denver® pleuroperitoneal shunt in one such patient. A 54-year-old Japanese man, who had previously undergone left nephrectomy, was admitted urgently to our department because of a high C-reactive protein (CRP) level, right pleural effusion, and right renal abscess. Because antibiotics proved ineffective and his general state was deteriorating, he underwent emergency insertion of a thoracic drainage tube and nephrectomy, and hemodialysis was started. Although his general state improved slowly thereafter, the pleural effusion, which was unilateral and transudative, remained refractory and therefore he needed to be on oxygenation. To control the massive pleural effusion, a pleuroperitoneal shunt was inserted. Thereafter, his respiratory condition became stable without oxygenation and he was discharged. His general condition has since been well. Although pleural effusion is a common complication of maintenance hemodialysis, few reports have documented the use of pleuroperitoneal shunt to control refractory pleural effusion. Pleuroperitoneal shunt has been advocated as an effective and low-morbidity treatment for refractory pleural effusion, and its use for some patients with recurrent pleural effusion has also been reported, without any severe complications. In the present case, pleuroperitoneal shunt improved the patient’s quality of life sufficiently to allow him to be discharged home without oxygenation. Pleuroperitoneal shunt should be considered a useful treatment option for hemodialysis patients with refractory pleural effusion.

Keywords: Refractory pleural effusion, Hemodialysis, Pleuroperitoneal shunt

Background

Pleural effusion is a common complication in hemodialysis patients, developing in approximately 20% of all hospitalized patients receiving hemodialysis [1]. The common etiologies of pleural effusion in this patient group are heart failure, volume overload, parapneumonic effusion, tuberculotic pleuritis, and uremic pleuritis [2]. Although symptomatic pleural effusion has been traditionally treated by repeated thoracentesis and chest tube drainage, reaccumulation of pleural effusion often occurs within a few weeks of the procedure.

Pleuroperitoneal shunt is a relatively non-invasive method for management of refractory pleural effusion by manual pumping of pleural fluid into the peritoneal cavity [3]. Since its introduction in 1979 (Denver Biomedical Colorado, USA), several modifications have been made. Here, we report the usefulness of pleuroperitoneal shunt for treatment of refractory pleural effusion in a patient receiving maintenance hemodialysis.

Case presentation

A 55-year-old Japanese man with a 40-year medical history of pruritus and asthma was admitted to our hospital with a 1-week history of fever, chills and arthralgia. 1 year previously, he had been admitted to our hospital because of sepsis, left renal abscess and subcapsular renal hematoma, necessitating left nephrectomy. 7 and 4 months before this admission, he had been twice admitted to our hospital because of sepsis and urinary infection. On admission, the patient was 166.8 cm tall and weighed 58.0 kg. His temperature was 36.5 °C, pulse 92 beats per minute, blood pressure 131/95 mmHg, and oxygen saturation 96% on ambient air. He appeared mildly unwell and in pain. Left conjunctival haemorrhage and pitting edema in the bilateral lower legs were confirmed, but other physical parameters were within normal limits. He had been treated with 15 mg of prednisolone for severe pruritus and asthma. Laboratory examinations demonstrated anemia, thrombocytopenia, renal dysfunction, coagulation abnormalities, and elevation of the CRP level (Table 1). Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) revealed right pleural effusion, and abdominal CT demonstrated an abscess and free air in the right kidney and right urolithiasis (Fig. 1). Escherichia coli was detected from two sets of blood culture and urine culture. He was diagnosed as having sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation due to right renal abscess, as well as right pleural effusion. Initial therapy with intravenous infusion of meropenem and thrombomodulin was started, along with continuous intravenous infusion of heparin and platelet transfusion. The elevated inflammatory parameters ameliorated gradually after the start of therapy, but the coagulation abnormalities continued. Because the right pleural effusion gradually worsened and oxygen supply was needed, thoracentesis was performed on the fifth day after admission. This aspirated thick yellow fluid, and immediate relief of the dyspnea was obtained. Fluid analysis revealed a cell count of 70, protein 1.0 g/dL, albumin 0.6 g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 89 IU/L, serum protein 4.5 g/dL, albumin 2.2 g/dL, and LDH 444 IU/L, suggesting transudative features. Cytological studies of the fluid and smears for acid-fast bacilli and routine cultures were negative. Pleural fluid amylase and adenosine deaminase levels were normal. 7 days after admission, the patient suddenly developed lower back pain, and abdominal CT suggested right renal rupture. Emergency right nephrectomy was performed by the urology team and maintenance hemodialysis was started using an indwelling catheter inserted into the right internal jugular vein. Intensive care, including hemodialysis therapy, allowed his condition to improve gradually except for right pleural effusion. Because the patient required thoracentesis frequently for recurrent dyspnea, a drainage tube was inserted into the right thorax. Periodic examinations suggested that the pleural effusion was transudative, similar to that at admission. Drainage of more than 500 ml of fluid per day made it difficult to remove the tube, and the patient was kept on oxygenation. Because inadequate dialysis with fluid overload was considered as the most likely cause of the refractory pleural effusion, the hemodialysis regimen was intensified based on his respiratory condition, BNP level and X-ray, but the effusion continued. At 123 days after admission, a pleuroperitoneal shunt was placed under general anesthesia to control the refractory pleural effusion (Denver® Mihama Medical, Inc, Tokyo, Japan). A small incision was made in the right rectus muscle along the ipsilateral anterior axially line at the level of the sixth rib for creation of a small percutaneous pocket to contain the pump apparatus. A tunnel was created above the rib and the peritoneal arm was introduced into the peritoneal cavity. The pleural arm was passed subcutaneously from the rectus muscle incision to the thoracic incision. It was then inserted into the pleural cavity and the incisions were closed. The chamber of the pump body was compressed frequently each day by the patient to transfer the pleural effusion into the peritoneal cavity. Five hundred compressions each day kept his respiratory condition stable without oxygenation. There were no adverse events, including shunt closure, infection and breakage. He was discharged home at 187 days after admission and his general condition has since remained good without shunt failure (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission to our hospital

| Blood count | |

| WBC | 13,960 /ul |

| Neu | 97.0% |

| Ba | 0.1% |

| Eo | 0.0% |

| Ly | 0.7% |

| Mo | 1.4% |

| RBC | 284 × 104 /ul |

| Hb | 8.7 g/dL |

| Ht | 26.2% |

| Plt | 2.1 × 104 /ul |

| Coagulation | |

| APTT | 31.6 s |

| Control | 32.9 s |

| PT | 115 % |

| PT-INR | 0.94 |

| Fibrinogen | 419 mg/dL |

| FDP | 33.5 µg/mL |

| d-dimer | 16.0 µg/mL |

| Urinalysis | |

| Protein | (2+) |

| Occult blood | (2+) |

| WBC | (3+) |

| Urinary sediment | |

| RBC | 1–4 /hpf |

| WBC | > 100 /hpf |

| Serum chemistry | |

| TP | 5.1 g/dL |

| Alb | 2.5 g/dL |

| BUN | 90.7 mg/dL |

| Cr | 8.59 mg/dL |

| UA | 11.7 mg/dL |

| Na | 136 mEq/L |

| K | 5.3 mEq/L |

| Cl | 107 mEq/L |

| Ca | 7.3 mg/dL |

| iP | 7.1 mg/dL |

| Fe | 15 µg/dL |

| Fer | 518.3 ng/mL |

| TB | 0.3 mg/dL |

| AST | 23 IU/L |

| ALT | 18 IU/L |

| LDH | 412 IU/L |

| ALP | 251 IU/L |

| BNP | 352.4 pg/L |

| CRP | 20.01 mg/dL |

| Procalcitonin | 42.92 ng/mL |

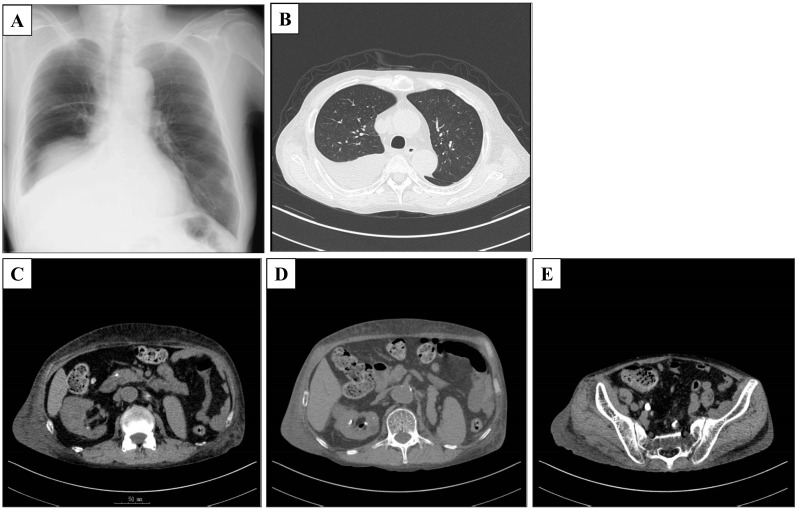

Fig. 1.

X-ray and CT scan on admission. a, b Right pleural effusion. c Right renal abscess. d Free air in the right kidney. e Right urolithiasis

Fig. 2.

Clinical course of the patient after starting hemodialysis. a Indwelling catheter inserted into the right internal jugular vein. b, c Right pleural effusion. A drainage tube was inserted into the right thorax (b). Soon after the tube was removed, right pleural effusion developed (c). d, e Chest and abdominal X-ray on the insertion of the pleuroperitoneal shunt. f On discharge. The right pleural effusion was improved by the pleuroperitoneal shunt

Discussion

Pleural effusions are common in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis and can sometimes be life threatening. Jarratt et al. reported that pleural effusions occurred in 21% of hospitalized patients receiving long-term hemodialysis and resulted from heart failure in 46% and non-heart failure (infection, neoplasm and so-called uremic pleuritis) in 54% [4]. Uremic pleuritis is estimated to develop in 3–10% of patients with advanced renal failure [5]. Pleural effusion generally resolves with continued dialysis over several weeks, although some cases may recur later [6]. The property of the effusion, whether exudative or transudative, is important for differential diagnosis, and Light’s criteria may be of help in this respect [7]. Exudative effusion can result from infection, malignant tumor, collagen disease, and pulmonary embolism, whereas transudative effusion can be due to congestive heart failure (CHF), liver cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, and malnutrition. In general, bilateral effusions are the most common distribution in CHF. But Beck et al. have reported that 36.5% of CHF-associated pleural effusions are asymmetric and right-side effusion is more frequent compared with left-side effusion [8]. In our patient, transudative effusion was demonstrated on the basis of Light’s criteria and his malnutrition and CHF were considered as the most likely cause of refractory pleural effusion. Systemic therapy using antibiotics, thoracentesis, and hemodialysis was unable to relieve his dyspnea, and a pleuroperitoneal shunt was placed in his body to control the refractory pleural effusion and improve his respiratory condition without oxygenation.

A pleuroperitoneal shunt is a specially designed silicone medical device consisting of a pump chamber that can be manually compressed with two catheters and transfers fluid from the pleural cavity to the peritoneal cavity. This pump can overcome the pressure gradient between the pleural and peritoneal cavities by compressing a bulb that houses a one-way valve, forcing flow from the chest to the abdomen. Although repeated thoracentesis and chest tube drainage often reaccumulate pleural effusion by the loss of protein and nutrients in the pleural fluid, a larger size of peritoneum compared with the size of pleura enables reabsorbs the fluid and nutrients from the pleural effusion. It allows the patient to improve mobility and respiration, while maintaining critical protein and nutrients in the pleural fluid [3]. Historically, a surgical approach has been used to treat this condition. However, over the last decade, percutaneous placement has become more common to minimize patient trauma and procedural risk, and Petrou et al. have reported low postoperative morbidity and mortality rates [9]. Ponn et al. described in detail the insertion of a shunt [10]. To our knowledge, however, this has not been reported previously for a hemodialysis patient with refractory pleural effusion.

Compared with the Denver® peritoneal venous shunt for patients with refractory ascites, few reports have documented the use of a pleuroperitoneal shunt for refractory pleural effusion. The usefulness of pleuroperitoneal shunts has been previously documented in patients with symptomatic malignant and benign effusion and chylothorax [11–15]. The majority of patients have been reported to show some symptomatic improvement, and few complications have been associated with its placement or long-term use. Genc et al. estimated that the early and late complication rate was 14.8% for patients treated with a pleuroperitoneal shunt for malignant pleural effusion, including shunt occlusion, infection, and tumor seeding in the peritoneal cavity [16]. Tzeng et al. reported that evaluation of factors including a history of abdominal surgery, performance status, pleural fluid cell counts and differential cell counts, blood biochemistry, and cytology revealed no significant differences between patients who suffered shunt failure and those who retained patent shunts [17]. To prevent infection and tumor seeding, examination of pleural fluid by Gram staining, culture, and cytology should be performed before implanting the pleuroperitoneal shunt [18]. In our patient, examinations gave negative results and percutaneous placement was performed to improve his respiratory condition while retaining nutritional elements, thus allowing safe hemodialysis. Pleuroperitoneal shunt proved to be an effective alternative treatment for this patient.

Conclusion

We have reported an experience of successful treatment of refractory pleural effusion using a pleuroperitoneal shunt in a patient receiving hemodialysis. Although pleural effusion is a common complication in the maintenance of hemodialysis patients, few reports have documented the use of a pleuroperitoneal shunt to control refractory pleural effusion. The advantage of a peritoneal shunt is to remove pleural effusion while maintaining critical protein and nutrients without any severe complications. In the present case, the pleuroperitoneal shunt improved the patient’s quality of life sufficiently to allow him to be discharged home without oxygenation. Pleuroperitoneal shunt should be considered a useful treatment option for hemodialysis patients with refractory pleural effusion.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the medical staff who managed this patient at our Division of Clinical Nephrology and Rheumatology.

Author contributions

MH, TI, YY, KM, SM, DK, and HK were involved in the clinical care of the patient, managed the literature searches, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IN helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Availability of data and material

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article was included within the article and its additional file.

Contributor Information

Masato Habuka, Phone: +81-25-281-5151, Email: lucky_palace1010@yahoo.co.jp.

Toru Ito, Email: itotoru.gt@gmail.com.

Yuta Yoshizawa, Email: callofduty4438@gmail.com.

Koji Matsuo, Email: ko.matsu.notre@gmail.com.

Shuichi Murakami, Email: rxm00337@nifty.com.

Daisuke Kondo, Email: disk@pastel.ocn.ne.jp.

Hiroshi Kanazawa, Email: kanazawa@niigataminami-hp.com.

Ichiei Narita, Email: naritai@med.niigata-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Bakirci T, Sasak G, Ozturk S, Akcay S, Sezer S, Haberal M. Pleural effusion in long-term hemodialysis patients. Transpl Proc. 2007;39(4):889–91. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rashid-Farokhi F, Pourdowlat G, Nikoonia MR, Behzadnia N, Kahkouee S, Nassiri AA, Masjedi MR. Uremic pleuritis in chronic hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2013;17(1):94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2012.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.© 2011 CareFusion Corporation or one of its subsidiaries. All rights reserved. Denver and Silique are trademarks or registered trademarks of CareFusion Corporation or one of its subsidiaries. LIT12007en-ED01. https://www.bd.com/Documents/international/brochures/interventionalspecialties/IS_Denver-ascites-shunts_BR_EN.pdf

- 4.Jarratt MJ, Sahn SA. Pleural effusions in hospitalized patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Chest. 1995;108(2):470–474. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.2.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher JF. Uremic pleuritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10(1):19–22. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(87)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Harby A, Al-Furayh O, Al-Dayel F, Al-Mobeireek A. Pleural effusion in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Ann Saudi Med. 2006;26(2):145–146. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2006.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, Ball WC., Jr Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77(4):507–513. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Straus SE. Does this patient have a pleural effusion? JAMA. 2009;301(3):309–317. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrou M, Kaplan D, Goldstraw P. Management of recurrent malignant pleural effusions. The complementary role talc pleurodesis and pleuroperitoneal shunting. Cancer. 1995;75(3):801–805. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950201)75:3<801::AID-CNCR2820750309>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponn RB, Blancaflor J, D’Agostino RS, Kiernan ME, Toole AL, Stern H, et al. Pleuroperitoneal shunting for intractable pleural effusions. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51(4):605–609. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)90319-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Little AG, Ferguson MK, Golomb HM, Hoffman PC, Vogelzang NJ, Skinner DB, et al. Pleuroperitoneal shunting for malignant pleural effusions. Cancer. 1986;58(12):2740–2743. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861215)58:12<2740::AID-CNCR2820581231>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cimochowski GE, Joyner LR, Fardin R, Sarama R, Maran A. Pleuroperitoneal shunting for recalcitrant pleural effusions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986;92(5):866–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little AG1, Kadowaki MH, Ferguson MK, Staszek VM, Skinner DB. Pleuro-peritoneal shunting. Alternative therapy for pleural effusions. Ann Surg. 1988;208(4):443–450. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198810000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy MC1, Newman BM, Rodgers BM. Pleuroperitoneal shunts in the management of persistent chylothorax. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48(2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milsom JW, Kron IL, Rheuban KS, Rodgers BM. Chylothorax: an assessment of current surgical management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;89(2):221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genc O, Petrou M, Ladas G, Goldstraw P. The long-term morbidity of pleuroperitoneal shunts in the management of recurrent malignant effusions. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18(2):143–146. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(00)00422-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzeng E, Ferguson MK. Predicting failure following shunting of pleural effusions. Chest. 1990;98(4):890–893. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aydin Y, Turkyilmaz A, Intepe YS, Eroglu A. Malignant pleural effusions: appropriate treatment approaches. Eurasian J Med. 2009;41(3):186–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]