Abstract

Autoimmune diseases are sometimes associated with immune-mediated renal diseases and cryoglobulinemia is one of the causes. Cryoglobulinemia and cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis associated with primary Sjögren’s syndrome are most frequent condition among non-hepatitis C virus-related condition. Its typical renal manifestation shows high amount of proteinuria with microscopic hematuria and renal insufficiency. We describe a case of 72-year-old woman with Hashimoto disease, autoimmune hepatitis, Sjögren’s syndrome, and immune-related pancytopenia complicated by cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Before kidney biopsy, tubulointerstitial nephritis probably due to Sjögren’s syndrome was suspected because of persistent hematuria without significant proteinuria and developing mild renal dysfunction over 6 months. The developing renal dysfunction associated with isolated hematuria is uncommon in glomerular diseases. Kidney biopsy, however, revealed established membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with subendothelial deposits consisting of tubular structures with IgM, IgG, and C3 staining. Corticosteroids plus mycophenolate mofetil therapy successfully normalized renal function. Physician should not overlook cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis, which is potentially poor prognosis, even if urinalysis shows only persistent isolated hematuria in patients with autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Autoimmune disease; Cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis; Isolated hematuria; Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; Mycophenolate mofetil, Sjögren’s syndrome

Introduction

Autoimmune diseases are sometimes associated with a variety of immune-mediated renal disease. Cryoglobulinemia in the presence of chronic immune stimulation from autoimmune diseases is one of the causes. Cryoglobulinemia and cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis (CG) associated with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) are most frequent condition among non-hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related condition [1]. Renal manifestations of non-HCV-related CG are variable and its typical renal manifestation includes high amount of proteinuria with microscopic hematuria and renal insufficiency [1, 2]. Most kidney specimens of CG showed membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) with subendothelial deposits with or without organized structures [1, 3].

It is known that renal involvement in primary SS is common, being up to 42% [4]. Primary SS is also reported to cause various glomerular lesions, such as MPGN with or without CG, membranous nephropathy [5, 6], and even ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis [7]. However, the most frequent renal lesion in primary SS is tubulointerstitial nephritis [1]. Therefore, we may encounter the patients with SS showing a variety of renal pathology with various renal manifestations.

We herein report a patient with MPGN due to CG in the course of Hashimoto disease, autoimmune hepatitis, SS, and immune-related pancytopenia, who presented uncommon renal manifestation of persistent isolated hematuria and mild renal dysfunction by glomerular injury and thus was initially suspected of tubulointerstitial nephritis caused by SS.

Case report

A 72-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital to evaluate isolated hematuria and renal dysfunction. She reported a 30-year history of Hashimoto disease and a 22-year history of SS and autoimmune hepatitis. In addition, she had a history of hypertension and dyslipidemia. She was referred to our hospital 2 months ago because of mild degree of pancytopenia. Bone-marrow aspiration showed normal cell number and morphology. Though she showed no apparent activity of her autoimmune diseases, immune-related pancytopenia was suspected. On the other hand, isolated microscopic hematuria was newly found 6 months ago. With persistent hematuria, serum creatinine was gradually increased from 0.61 to 1.13 mg/dl over 6 months. She had been taking levothyroxine sodium hydrate 100 mg/day for Hashimoto disease, ursodeoxycholic acid 300 mg/day for autoimmune hepatitis, candesartan cilexetil/amlodipine besilate 8 mg/5 mg/day for hypertension, and pitavastatin calcium 2 mg/day for dyslipidemia.

On admission, her physical examination was unremarkable without skin, joint, and neural findings. Blood pressure was 110/60 mmHg. Laboratory data are listed in Table 1. The patient showed that high-grade glomerular hematuria without significant proteinuria, positive urinary red-blood-cell cast, slightly increase in a marker for proximal tubular damage, anemia, renal dysfunction, and hyperuricemia. Immunological findings showed low complement 4, negative hepatitis B and C serologies, negative anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, positive autoantibodies compatible to SS, and positive cryoglobulins. Since decrease in urine volume was not found and FENa was 1.76, renal dysfunction on admission was considered not to be caused by pre-renal kidney failure. Chest X-ray and chest computed tomography images did not show pulmonary lesions. The patient had sicca symptoms at the time of diagnosis of SS, but she did not complain about them on admission. However, Schirmer tear test and Saxon test were positive. Though we noticed that the patient had cryoglobulinemia and urinary red-blood-cell cast as nephritic urinary cast, tubulointerstitial nephritis probably due to SS was initially suspected because of renal insufficiency with isolated hematuria and increase in urinary N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase and urinary α1-microglobulin.

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission

| Urine | |

| Protein | – |

| Occult blood | 3+ |

| Red-blood cell | 50–99/high power field |

| White blood cell | 1–4/high power field |

| Red-blood-cell cast | Positive |

| Protein | 0.13 g/gCr |

| NAG | 24.5 U/L (0.7–11.2) |

| α1-microglobulin | 13.2 mg/L (< 11.9) |

| Complete blood count | |

| WBC | 4000/µL |

| Hb | 8.8 g/dL |

| MCV | 84.1 fL |

| MCHC | 28.0 pg |

| Platelet | 11.4 × 104/µL |

| Blood chemistry | |

| Total protein | 7.4 g/dL |

| Albumin | 4.1 g/dL |

| Urea nitrogen | 59.5 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.45 mg/dL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 23 IU/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 11 IU/L |

| Total bilirubin | 0.48 mg/dL |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 201 IU/L |

| γglutamyltransferase | 17 IU/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 194 IU/L |

| Na | 131 mEq/L |

| K | 4.7 mEq/L |

| Cl | 94 mEq/L |

| Triglyceride | 88 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol | 146 mg/dL |

| LDL cholesterol | 66 mg/dL |

| Fe | 36 µg/dL |

| TIBC | 245 µg/dL |

| Ferritin | 532.8 ng/mL |

| Free T3 | 1.85 pg/mL |

| Free T4 | 1.35 mg/dL |

| TSH | 1.36 µIU/mL |

| Estimated GFR | 27.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| Immunologic test | |

| IgG | 1130 mg/dL |

| IgA | 302 mg/dL |

| IgM | 42 mg/dL |

| IgE | 8 mg/dL |

| CH50 | 10 U/mL |

| C3 | 86 mg/dL |

| C4 | 2 mg/dL |

| C-reactive protein | 0.58 mg/dL |

| Rheumatoid factor | 23.7 U/mL |

| Antinuclear antibody | × 160 homogeneous and speckled patterns |

| Anti-DNA antibody | 1.0 IU/mL (< 9.0) |

| Anti-SS-A antibody | 240 U/ml (< 6.0) |

| Anti-SS-B antibody | 0.6 U/ml (< 6.0) |

| Anti-RNP antibody | 0.6 U/mL (< 4.0) |

| MPO-ANCA | 1.0 U/mL (< 3.4) |

| PR3-ANCA | 1.0 U/mL (< 3.4) |

| Cryoglobulin | Positive |

| HBs antigen | Negative |

| HCV antibody | Negative |

NAG N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase, TIBC total iron binding capacity, TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone, GFR, glomerular filtration rate, MPO-ANCA, myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, PR3-ANCA, proteinase 3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, HBs, hepatitis B surface antigen, HCV, hepatitis C virus. The values in the parentheses show the normal range

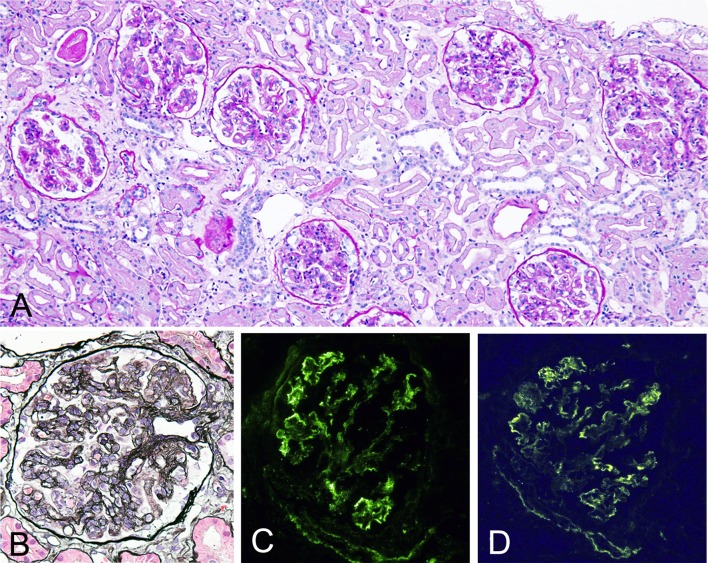

Kidney biopsy revealed global sclerosis in 11 out of 36 glomeruli. Rest of the glomeruli showed lobulation, diffuse endocapillary proliferation with infiltration of mononuclear and polymorph nuclear cells, mesangial proliferation, and glomerular capillary thickening with double contour (Fig. 1a, b). Mild degree of infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells in interstitial areas without tubulitis and vasculitis were observed (Fig. 1a). There were also mild-to-moderate patchy interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy and mild degree of atherosclerosis and arteriolar hyalinosis.

Fig. 1.

Light micrographs of renal tissues. a Glomeruli show lobulation, diffuse endocapillary proliferation, and mesangial proliferation. Mild degree of lymphocytes and plasma cell infiltrations in interstitial areas without vasculitis are seen. [periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining], original magnification ×200. b Glomerulus shows glomerular capillary wall thickening with double contour. (PAM-HE staining), original magnification ×400. c, d Immunofluorescence study shows positive IgM (c) and C3 (d) along glomerular capillary walls

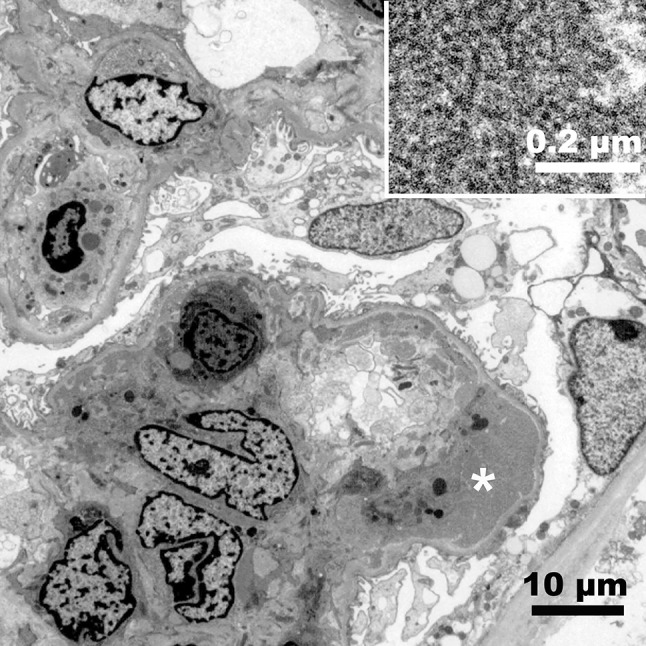

Immunofluorescence study showed strongly positive IgM, weakly positive IgG, weakly positive C3, strongly positive κ, and weakly positive λ along the glomerular capillary walls (Fig. 1c, d). C1q and IgA were negative. Electron microscopy showed large subendothelial deposits with tubular structures, small amount of mesangial deposits, and macrophages infiltration within glomerular capillary lumen (Fig. 2). There was only partial glomerular epithelial effacement despite large amount of subendothelial deposits (Fig. 2). MPGN due to CG and nephrosclerosis probably due to hypertension and/or hyperlipidemia was diagnosed.

Fig. 2.

Electron micrograph of a glomerulus. Infiltrating cells in the capillary lumen, mesangial proliferation, and subendothelial electron dense deposits are seen. There is only limited epithelial effacement. Bar = 10 µm. Incest; tubular structures in the subendothelial deposits (*). Bar = 0.2 µm

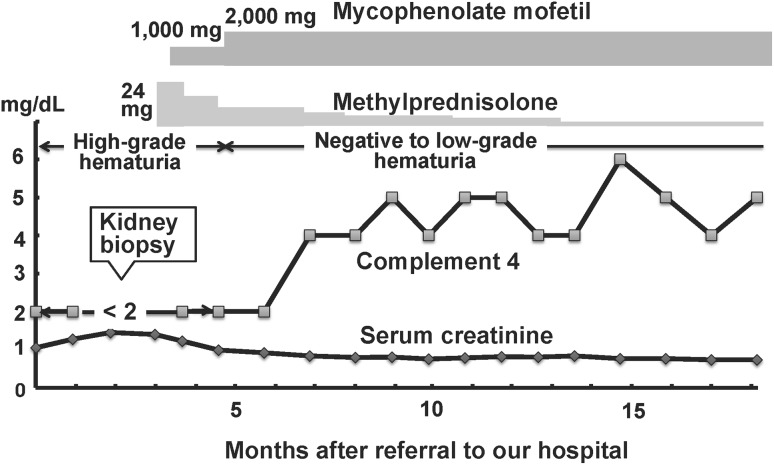

To suppress the production of cryoglobulin probably due to SS, 24 mg/day of oral methylprednisolone and then 1000 mg/day of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) were initiated (Fig. 3). After the treatment, dose of MMF was increased to 2000 mg/day with gradually tapering methylprednisolone. High-grade hematuria became negative to low-grade hematuria in 2 months, complement 4 level was increased from < 2 to 4 mg/dL in 4 months, and renal dysfunction became almost normalized in 8 months after the treatment. Anemia was ameliorated in 3 months, but slight thrombocytopenia was sustained after the treatment. Cryoglobulin was confirmed to become negative 9 months after the treatment.

Fig. 3.

Clinical course of the patient with methylprednisolone and mycophenolate mofetil

Discussion

We reported a patient with secondary MPGN type 1 due to CG in the clinical course of autoimmune diseases. We initially suspected that her renal manifestation was caused by tubulointerstitial nephritis, because in addition to isolated hematuria, markers for proximal tubular damage were increased and tubulointerstitial nephritis is known as the most frequent renal manifestation in primary SS [5]. On the other hand, the patient showed positive urinary red-blood-cell cast, suggesting the existence of glomerular injury. Though anticoagulation-related nephropathy could show acute kidney injury and/or chronic kidney disease with isolated glomerular hematuria and increased markers for proximal tubular damage [8], our patient did not use any anticoagulants. Unexpectedly, kidney biopsy revealed established MPGN due to CG.

Cryoglobulins are generated by clonal expansion of B cells which occurs in lymphoproliferative disorders or in the presence of chronic immune stimulation from autoimmune diseases or infections. The patient did not have infection and lymphoproliferative disorders, but had autoimmune diseases. It is known that CG by the mixed form of cryoglobulinemia (Type II contains monoclonal IgM and polyclonal IgG, while type III contains polyclonal IgM and polyclonal IgG) in patients with primary SS is most frequent among non-HCV condition [1]. It is reported that the frequency of occurrence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is higher in SS patients. In addition, 35% of patients with thyroid disorder showed sicca features, which makes it difficult to determine whether our patient is primary SS or secondary SS associated with autoimmune thyroiditis [9]. Although cryoglobulin typing could not be determined in our case, the depositions of C3 along with IgM and IgG in the glomerular capillary walls and the subendothelial deposits with tubular structures indicated the immune complex formation and presence of mixed cryoglobulinemia [3]. It is possible that staining of strongly positive κ and weakly positive λ in our patient explains type II cryoglobulinemia containing monoclonal IgM and polyclonal IgG.

About 20% of patients with cryoglobulinaemia present with nephropathy at diagnosis and 30% have renal complications during the disease course and renal features are indolent in nearly half the patients, with proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, red-blood-cell casts, and varying degrees of renal failure [10]. According to the French CryoVas survey, it was reported that hematuria, proteinuria ≥ 1 g/day, hypertension, and renal failure were observed in 97.4, 84.8, 85.3, and 82.3% of 80 patients with biopsy-proven CG at presentation, respectively [2]. Proteinuria ≥ 1.0 g/day or hematuria was found in 100 or 93.8% of 18 CG cases due to primary SS, respectively [2]. Thus, our patient’s renal manifestation showing persistent microscopic hematuria without significant proteinuria with renal dysfunction is rare. In general, the developing renal dysfunction associated with isolated glomerular hematuria is uncommon. Though it is conceivable that severe endocapillary proliferation can explain the reduced glomerular filtration areas, resulting in the reduced GFR, it remains unknown why proteinuria was not observed in our patient.

It is reported that noninfectious mixed CG shows variety of clinical course after the treatment and has a poor long-term outcome with severe infection as a main cause of death [2]. The treatment of CG has not established. If possible, the underlying cause should be treated or removed. Though the significant symptoms of SS were not observed, SS is most relevant cause of CG in our patient. Since primary SS is reported to be associated with pancytopenia [11], it might be possible that SS was active at the onset of cryoglobulinemia in our patient. Patients with SS and concomitant cryoglobulinemia should be treated early due to the high risk of adverse outcome, particularly vasculitis, B-cell lymphoma, and death [12]. Current treatments of CG involve immunosuppression or selective depletion of B cells. It is reported that combinations of steroids with either cyclophosphamide or rituximab should be preferred to steroids alone as first-line therapy in noninfectious CG [2]. Therefore, we determined to use combination therapy. However, the best combinations of steroids with immunosuppressants are not known. Mycophenolate sodium was reported to be effective to treat primary SS [13] and mycophenolic acid-containing compounds such as MMF was also effective for primary SS-associated interstitial nephritis and Sjögren Sensory Neuronopathy [14, 15]. MMF was reported to be effective for reducing the formation of new antibodies in patients with CG even due to hepatitis C [16]. The optimal dose of MMF to use for SS and CG is unknown. In addition to methylprednisolone, we used MMF to our patient and all parameters such as hematuria, renal dysfunction, low C4 and cryoglobulin became improved at 2000 mg/day of MMF. The long-term efficacy of treatment for CG remains uncertain in patients with SS.

Our case emphasizes that it is possible that even established CG could show isolated persistent hematuria with developing renal dysfunction. Physicians should keep in mind the possible presence of CG in patients with autoimmune diseases in particular including SS who show newly appeared hematuria and renal dysfunction to allow to make an early diagnosis and treatment of CG that is potentially poor prognosis [17].

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Hiromi Yamaguchi for her technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

References

- 1.Matignon M, Cacoub P, Colombat M, Saadoun D, Brocheriou I, Mougenot B, Roudot-Thoraval F, Vanhille P, Moranne O, Hachulla E, Hatron PY, Fermand JP, Fakhouri F, Ronco P, Plaisier E, Grimbert P. Clinical and morphologic spectrum of renal involvement in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia without evidence of hepatitis C virus infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88:341–348. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181c1750f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaidan M, Terrier B, Pozdzik A, Frouget T, Rioux-Leclercq N, Combe C, Lepreux S, Hummel A, Noël LH, Marie I, Legallicier B, François A, Huart A, Launay D, Kaplanski G, Bridoux F, Vanhille P, Makdassi R, Augusto JF, Rouvier P, Karras A, Jouanneau C, Verpont MC, Callard P, Carrat F, Hermine O, Léger JM, Mariette X, Senet P, Saadoun D, Ronco P, Brochériou I, Cacoub P, Plaisier E. CryoVas study group. Spectrum and prognosis of noninfectious renal mixed cryoglobulinemic GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1213–1224. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand A, Krishna GG, Sibley RK, Kambham N. Sjögren syndrome and cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:532–535. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monti G, Galli M, Invernizzi F, Pioltelli P, Saccardo F, Monteverde A, Pietrogrande M, Renoldi P, Bombardieri S, Bordin G, Candela M, Ferri C, Gabrielli A, Mazzaro C, Migliaresi S, Mussini C, Ossi E, Quintiliani L, Tirri G, Vacca A. Cryoglobulinaemias: a multi-centre study of the early clinical and laboratory manifestations of primary and secondary disease. GISC. Italian Group for the Study of Cryoglobulinaemias. QJM. 1995;88:115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maripuri S, Grande JP, Osborn TG, Fervenza FC, Matteson EL, Donadio JV, Hogan MC. Renal involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1423–1431. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00980209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goules A, Masouridi S, Tzioufas AG, Ioannidis JP, Skopouli FN, Moutsopoulos HM. Clinically significant and biopsy-documented renal involvement in primary Sjögren syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79:241–249. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morimoto C, Fujigaki Y, Tamura Y, Ota T, Shibata S, Asako K, Kikuchi H, Kono H, Kondo F, Yamaguchi Y, Uchida S. Emergence of smoldering ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis during the clinical course of mixed connective tissue disease and Sjögren’s syndrome. Intern Med. 2017 doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.9844-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheeler DS, Giugliano RP, Rangaswami J. Anticoagulation-related nephropathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14:461–467. doi: 10.1111/jth.13229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeher M, Horvath IF, Szanto A, Szodoray P. Autoimmune thyroid diseases in a large group of Hungarian patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Thyroid. 2009;19:39–45. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramos-Casals M, Stone JH, Cid MC, Bosh X. The cryoglobulinaemias. Lancet. 2012;379:348–360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang L, Li XF, Huang CB, Wang GC, Zhang XW, Zhang ZL, Zhang X, Xiao WG, Dai L, Wang YF, Hu SX, Li HB, Gong L, Liu B, Sun LY, Zhang MJ, Zhang X, Li YZ, Du DS, Zhang SH, Sun YY, Zhang FC. Primary Sjögren syndrome in Han Chinese: clinical and immunological characteristics of 483 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e667. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retamozo S, Gheitasi H, Quartuccio L, Kostov B, Corazza L, Bové A, Sisó-Almirall A, Gandía M, Ramos-Casals M, De Vita S, Brito-Zerón P. Cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis at diagnosis predicts mortality in primary Sjögren syndrome: analysis of 515 patients. Rheumatology. 2016;55:1443–1451. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willeke P, Schlüter B, Becker H, Schotte H, Domschke W, Gaubitz M. Mycophenolate sodium treatment in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome: a pilot trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R115. doi: 10.1186/ar2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koratala A, Reeves WH, Segal MS. Tubulointerstitial nephritis in sjögren syndrome treated with mycophenolate mofetil. J Clin Rheumatol. 2017;23:402–403. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira PR, Viala K, Maisonobe T, Haroche J, Mathian A, Hié M, Amoura Z, Cohen Aubart F. Sjögren sensory neuronopathy (Sjögren Ganglionopathy): long-term outcome and treatment response in a series of 13 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3632. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colucci G, Manno C, Grandaliano G, Schena FP. Cryoglobulinemic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: beyond conventional therapy. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75:374–379. doi: 10.5414/CNP75374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorevic PD, Kassab HJ, Levo Y, Kohn R, Meltzer M, Prose P, Franklin EC. Mixed cryoglobulinemia: Clinical aspects and long-term follow-up of 40 patients. Am J Med. 1980;69:287–308. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]