Abstract

We report a case of distal partial trisomy 1 from q32.1 to 41 that have exhibited proteinuric glomerulopathy. The patient was a 17-year-old adolescent with clinical features of low birth weight, mild mental retardation and mild deafness, from the birth. He exhibited non-nephrotic range proteinuria with the mild obesity since the age of sixteen. Image studies did not reveal morphological abnormalities of the kidneys. Renal biopsy findings showed no definitive evidence of primary glomerular diseases, and were characterized by a very low glomerular density, glomerulomegaly and focal effacement of podocyte foot processes. Therapies with dietary sodium restriction, body weight reduction and the administration of angiotensin receptor blocker markedly reduced his proteinuria. It was likely that mismatch between congenital reduction in the nephron number and catch-up growth of the whole body size played a major role in the development of glomerular hyperperfusion injury. At present, the direct contribution of genetic factors due to this chromosomal disorder to such a substantial reduction in the nephron number remains uncertain.

Keywords: Distal partial trisomy chromosome 1, Low birth weight, Nephron number, Catch-up growth, Proteinuria

Introduction

Distal partial trisomy 1q is a rare disorder, of which the phenotype has not been fully defined because of the heterogeneity of its genotypes. Patients with this chromosome disorder demonstrate a variety of clinical manifestations, such as intrauterine growth retardation, low weight at birth, hydronephrosis, and cardiovascular abnormalities [1–12]. However, there have been no reported cases with renal parenchymal disorders, including proteinuric glomerulopathy, among the patients with this chromosomal disorder.

Recent autopsy studies have identified much greater variability in the number of nephrons among individuals than previously suspected [13]. In humans, kidney development begins during the 9th week of gestation and continues until the 36th week. Importantly, no nephrons are formed after birth [14]. Thus, the intrauterine environment, such as nutrition and maternal factors, may substantially affect the nephron endowment of the fetus. Indeed, intrauterine growth retardation and/or a low weight at birth have been shown to be associated with a low nephron number and may be potential risk factors for chronic kidney disease in later life [15–18]. A low nephron number can lead to compensatory hyperfiltration of glomeruli, which may result in histopathological phenotypes such as glomerular hypertrophy and focal glomerular injuries [19, 20].

A history of low birth weight is sometimes associated with patients with genetic comorbidities. However, the renal complications in such patients have not been fully discussed. We herein report a case with partial trisomy of chromosome 1 presenting with persistent proteinuria and a clinical history of low weight at birth. The pathogenesis potentially involved in the proteinuric glomerulopathy observed in this case is discussed.

Case report

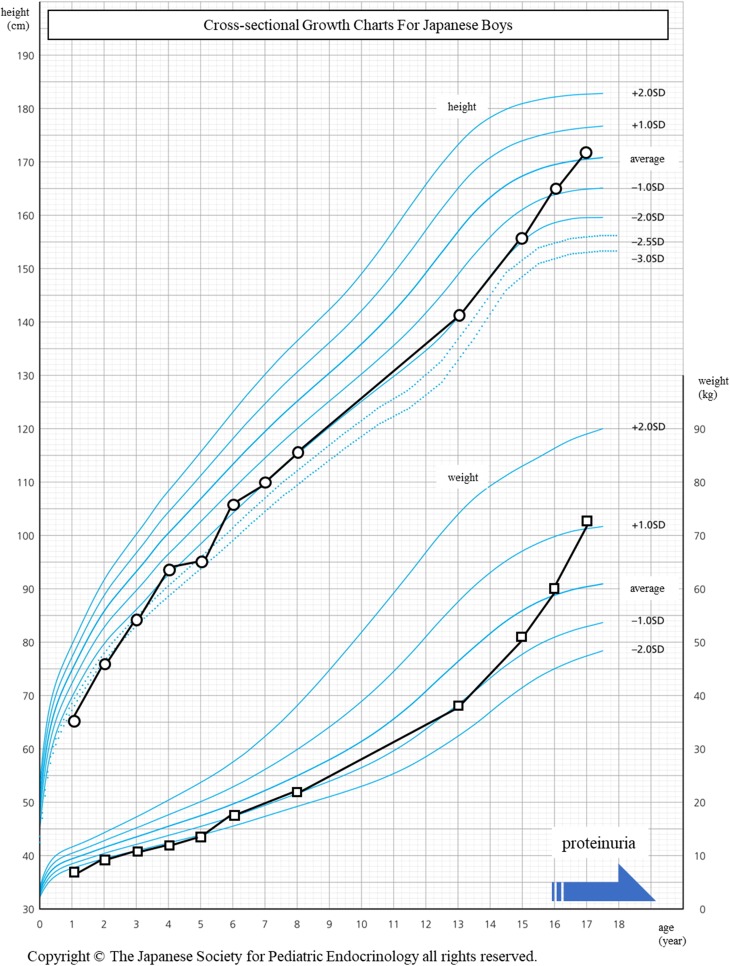

The patient was a 17-year-old adolescent with clinical features of a low birth weight, mild mental retardation, and mild deafness. His birth weight had been 1550 g at 35 weeks of gestation. He did not receive intensive care during the perinatal period. His childhood growth of height and weight was around the mean minus two standard deviations compared to the average Japanese population (Fig. 1) [21]. At 13 years of age, he had been diagnosed with partial trisomy of chromosome 1 using a chromosomal test. The CGH microarray revealed arr 1q32.1-q41(204, 637, 883–221, 374, 742) × 3. He was ultimately diagnosed with partial trisomy of chromosome 1 from 1q32.1-q41. He had no apparent episodes of urinary infection, which are often found in patients with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT). His height and weight had caught up to the mean value among the Japanese population by 16 and 17 years of age, respectively. He had shown persistent proteinuria since 16 years of age and underwent medical checkups at our hospital.

Fig. 1.

The growth history of this case plotted on a growth chart of average values for Japanese boys. The increase in height and weight were around the mean minus two standard deviations compared to the average values of the Japanese population. Proteinuria first emerged at 16 years of age, when his weight caught up to the average value. The black and gray solid lines indicate the increase in the height and weight, respectively

A physical examination showed that his height, weight, body mass index, and blood pressure were 171 cm, 74.3 kg, 25.4 kg/m2, and 118/65 mmHg, respectively. No edema was noted. He did not present with low-set ears or proportion and limb shortening, although some patients with trisomy of chromosome 1 do show such findings. Blood tests showed that the serum creatinine was 0.69 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen was 12.0 mg/dL, total protein was 7.3 mg/dL, albumin was 4.4 mg/dL, uric acid was 5.0 mg/dL, fasting blood sugar was 99 mg/dL, and hemoglobin A1c was 4.9%. The serum levels of hepatobiliary enzyme, electrolytes, and lipids were within the normal ranges, and there were no abnormalities in a blood cell count examination. The serum levels of immunoglobulins were within the normal range, and anti-nuclear antibody and anti-streptolysin O were negative. In a 24-h urine collection test, the urinary protein excretion was 1.16 g, and the creatinine clearance rate was 98.6 ml/min. His estimated protein intake was 63.6 g/day, and salt excretion was 6.9 g/day in the urine. Hematuria was not detected in the urinary sediments. Computed tomography and abdominal ultrasonography detected no morphological abnormalities of the kidneys. The maximum lengths of the right and left kidneys were 9.9 and 10.2 cm, respectively.

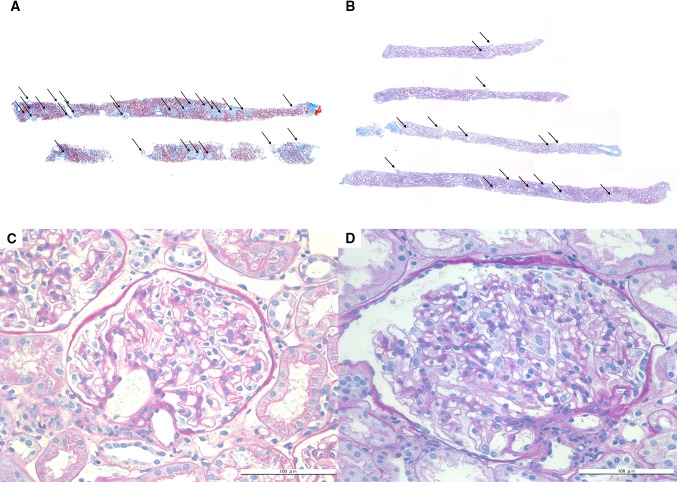

A renal biopsy was performed to evaluate the cause of the patient’s persistent proteinuria. Figure 2 shows the renal biopsy findings. In this case, the percentage of tubulointerstitial injury was approximately 5% of the total cortical area involved. Although 4 pieces of the biopsy specimen contained a sufficient amount of cortex area, only 15 glomeruli were identified. No globally or focally sclerotic glomeruli were detected in the specimen. The glomerular density, defined as the number of glomeruli per observed cortical area, was 0.8/mm2, which was markedly lower than the value in the biopsy specimens of healthy Japanese adult subjects (approximately 2.2–3.2/mm2 on average) [22, 23].

Fig. 2.

Renal biopsy findings by light microscopy. The representative renal biopsy findings in a 17-year-old male patient with minimal change nephrotic syndrome showing normal glomerular density (3.1/mm2) (a) and in this patient showing a low glomerular density (0.8/mm2) (b) are shown. The arrows indicate non-sclerotic glomeruli (Masson trichrome stain ×50). A glomerulus in a patient with minimal change nephrotic syndrome (c) and the extremely hypertrophied glomerulus (glomerulomegaly) found in this patient (d) (periodic acid-Schiff stain ×400)

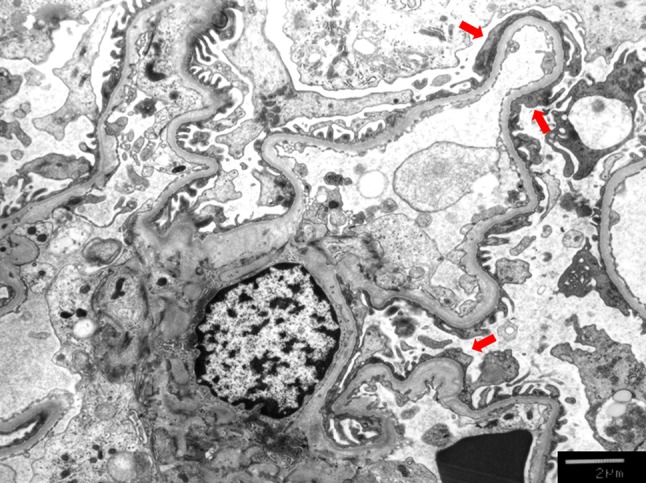

The glomeruli were markedly enlarged, showing a much larger mean maximal glomerular diameter (268 µm) and mean glomerular volume (10.3 × 106 µm3) than the mean glomerular volume of healthy Japanese adult subjects estimated using the same formula (approximately 2.4–2.5 × 106 mm3) [22, 23]. No specific staining patterns were identified by an immunofluorescent study including staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q. Electron microscopy revealed no remarkable abnormalities other than locally identified foot process effacement (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Electron microscopic findings. Focal foot process effacement (red arrow) was observed by an electron microscope. ×3000 original magnification

Therapies with dietary sodium restriction and body weight reduction were instructed, and 25 mg of losartan potassium was administered. His body weight was reduced to 71.1 kg in 3 months after diet therapy. The level of serum creatinine slightly increased to 0.71 mg/dL and urinary protein excretion rate decreased to 0.30 g/day, respectively.

Discussion

This is the first report of a patient with partial trisomy 1q who exhibited persistent proteinuria. The onset of proteinuria was insidious, without any signs of infection symptoms or edema formation, and the serum protein levels remained relatively stable throughout the clinical course. Histopathology of the renal biopsy specimen in this case showed no evidence of immune-mediated glomerular inflammatory changes or injuries. Quite the contrary, the specimen was characterized by a very low density and marked enlargement of the glomeruli. An electron microscopy study revealed that podocyte foot process fusions were only focally observed. Although the biopsy did not show any typical features of focal segmental glomerular sclerosis (FSGS), all of the clinical and histopathological features are consistent with secondary maladaptive glomerular injuries [19, 20]. The very low density and marked enlargement of the glomeruli, representing secondary maladaptive glomerular injuries, are found in the cases with the history of the low birth weight and are known as oligomeganephronia [19, 20]. In our case, combination therapy with body weight reduction and the administration of angiotensin receptor blocker markedly reduced the proteinuria, further supporting this idea.

The birth weight of the present case was not very low compared to that of most patients with oligomeganephronia, whose birth weight is usually very or extremely low. In addition, even though our patient showed only mild obesity, he showed marked glomerulomegaly and proteinuria. In general, only a minority of obese subjects shows apparent proteinuria and renal impairment. This suggests a possible involvement of “renal factors” in the development of glomerulopathy associated with obesity [24, 25]. These observations suggest that the nephron number endowment and obesity status were not severe enough to induce renal injury, implying that the chromosomal abnormality may have additionally influenced the renal involvement of this case.

Mutations in genes encoding proteins related to the podocyte function, such as nephrin and podocin, induce proteinuric renal diseases, including hereditary nephrotic syndrome with histological features of FSGS [26]. Among the more than 30 reported FSGS-causative genes, only NPHS2 (NM_014625), which encodes podocin, is related to chromosome 1. However, the location of NPHS2 on the chromosome is 1q25.2, which is different from that affected in the present case (1q32.1-q41) [27].

A low number of glomeruli can be caused by abnormalities of ureteric bud branching morphogenesis during kidney development [14]. Indeed, in our case, the kidney was smaller than the average population, although a renal biopsy showed that the nephrons were markedly enlarged. This suggests that the nephron number was quite low in our case. However, the low nephron number in our case was unlikely an acquired state, as imaging studies of the morphology showed no evidence of atrophic kidneys. In addition, no globally sclerotic glomeruli were identified, and the degrees of tubular atrophy or interstitial fibrosis were minimal on the biopsy. Chromosomal disorders are often complicated by CAKUT and such patients with CAKUT often develop tubulointerstitial injuries due to repeated episodes of urinary tract infection and urinary afterload due to vesicoureteral reflux and/or ureter obstruction [28]. In the present case, however, no apparent morphological abnormalities of the urinary tracts were detected on imaging studies. In addition, renal biopsy revealed no evidence of tubulointerstitial injuries, suggesting repeated episodes of urinary tract infection. It is, therefore, unlikely that the low number of nephrons is associated with the congenital origin of lower urinary tract abnormalities.

Recent autopsy studies have shown that polymorphisms within the GDNF and RET genes, which are the main genes involved in branching nephrogenesis, are associated with a low number of nephrons [14]. The GDNF and RET genes are located on chromosomes 5 and 10, respectively. This excludes the possibilities that the renal injury in our case occurred in association with the genes encoding GDNF and RET. Thus, the glomerulopathy and related proteinuria observed in our case were not likely to be associated with the major known genes encoding podocyte functions and overseeing nephron endowment. At present, however, we cannot exclude the possible contribution of as-yet-unknown and uncharacterized genes located on chromosome 1q that might have induced podocyte injury and/or glomerulopathy.

Koike et al. observed a low glomerular density and glomerular enlargement with FSGS, which were considered secondary maladaptive injuries, on renal biopsies among school-age children with a history of a low birth weight [29]. The present case was similar to a group of cases reported in that study characterized by a low birth weight history, the appearance of proteinuria at the timing of catch-up growth, and renal biopsy findings of a low glomerular density and glomerulomegaly. In this respect, our case fits well with the “low-nephron-endowment glomerular hyperfiltration hypothesis” [30]. In subjects with a history of a low birth weight, which is often found in patients with genetic comorbidities like the present case, the renal prognosis merits further study. Thus, continuous follow-up is required to detect renal complications and determine the outcomes in this group of chronic kidney disease patients at a high risk of progressing to end-stage renal disease.

In conclusion, we reported a case of proteinuric glomerulopathy in an adolescent with distal partial trisomy of chromosome 1. The clinical course and the characteristic renal biopsy findings observed in this case suggest that the nephron number-body size mismatch due to low nephron endowment and subsequent catch-up growth of the whole body may underlie the pathogenesis. At present, the contribution of genetic factors due to this chromosomal disorder remains uncertain.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this study were presented at the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week 2017, November 2017, New Orleans, LA.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

In this article, studies of human and animal participants are not included.

Informed consent

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Morris ML, Baroneza JE, Teixeira P, et al. Partial 1q duplications and associated phenotype. Mol Syndromol. 2016;6:297–303. doi: 10.1159/000443599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian M, Barber JC, Collinson MN, et al. Inverted duplication of 1q32.1 to 1q44 characterized by array CGH and review of distal 1q partial trisomy. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:793–797. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartsch C, Aslan M, Köhler J, et al. Duplication dup(1)(q32q44) detected by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH): further delineation of trisomies 1q. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2001;16:265–273. doi: 10.1159/000053926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark BK, Lowther GW, Lee WR. Congenital ocular defects associated with an abnormality of the human chromosome 1: trisomy 1q32- qter. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1994;31:41–45. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19940101-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duba HC, Erdel M, Löffler J, et al. Detection of a de novo duplication of 1q32-qter by fluorescence in situ hybridisation in a boy with multiple malformations: further delineation of the trisomy 1q syndrome. J Med Genet. 1997;34:309–313. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.4.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flatz S, Fonatsch C. Partial trisomy 1q due to tandem duplication. Clin Genet. 1979;15:541–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1979.tb00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimya Y, Yakut T, Egeli U, Ozerkan K. Prenatal diagnosis of a fetus with pure partial trisomy 1q32–44 due to a familial balanced rearrangement. Prenat Diagn. 1979;22:957–961. doi: 10.1002/pd.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowaczyk MJM, Bayani J, Freeman V, Watts J, Squire J, Xu J. De novo 1q32q44 duplication and distal 1q trisomy syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;120A:229–233. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polityko A, Starke H, Rumyantseva N, Claussen U, Liehr T, Raskin S. Three cases with rare interstitial rearrangements of chromosome 1 characterized by multicolor banding. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111:171–174. doi: 10.1159/000086388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steffensen DM, Chu EHY, Speert DP, Wall PM, Meilinger K, Kelch RP. Partial trisomy of the long arm of human chromosome 1 as demonstrated by in situ hybridization with 5S ribosomal RNA. Hum Genet. 1977;36:25–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00390432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Utine GE, Aktas D, Alanay Y, et al. Distal partial trisomy 1q: report of two cases and review of the literature. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27:865–871. doi: 10.1002/pd.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe S, Shimizu K, Ohashi H, et al. Detailed analysis of 26 cases of 1q partial duplication/triplication syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A:908–917. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoy WE, Bertram JF, Denton RD, et al. Nephron number, glomerular volume, renal disease and hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:258–265. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282f9b1a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland MR, Gubhaju L, Moore L, et al. Accelerated maturation and abnormal morphology in the preterm neonatal kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1365–1374. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverwood RJ, Pierce M, Hardy R, et al. Low birth weight, later renal function, and the roles of adulthood blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity in a British birth cohort. Kidney Int. 2013;84:1262–1270. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwinta P, Klimek M, Drozdz D, et al. Assessment of long-term renal complications in extremely low birth weight children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1095–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1840-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White SL, Perkovic V, Cass A, et al. Is low birth weight an antecedent of CKD in later life? A systematic review of observational studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:248–261. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berglund D, MacDonald D, Jackson S, et al. Low birthweight and risk of albuminuria in living kidney donors. Clin Transplant. 2014;28:361–367. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fetterman GH, Habib R, Fabrizio NS, Studnicki FM. Congenital bilateral oligonephronic renal hypoplasia with hypertrophy of nephrons: studies by microdissection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1969;52:199–207. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/52.2.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez MM, Gomez A, Abitbol C, Chandar J, Montané B, Zilleruelo G. Comparative renal histomorphometry: a case study of oligonephropathy of prematurity. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:945–949. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1800-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isojima T, Kato N, Ito Y, Kanzaki S, Murata M. Growth standard charts for Japanese children with mean and standard deviation (SD) values based on the year 2000 national survey. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2016;25:71–76. doi: 10.1297/cpe.25.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi A, Yamamoto I, Katsumata H, et al. Change in glomerular volume and its clinicopathological impact after kidney transplantation. Nephrology (Carlton) 2015;20(Suppl 2):31–35. doi: 10.1111/nep.12463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haruhara K, Tsuboi N, Kanzaki G, et al. Glomerular density in biopsy-proven hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:1164–1171. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuboi N, Utsunomiya Y, Kanzaki G, et al. Low glomerular density with glomerulomegaly in obesity-related glomerulopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:735–741. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07270711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okabayashi Y, Tsuboi N, Sasaki T, et al. Glomerulopathy associated with moderate obesity. Kidney Int Rep. 2016;1:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bierzynska A, Mccarthy H, Soderquest K. et. al. Genomic and clinical profiling of a national nephrotic syndrome cohort advocates a precision medicine approach to disease management. Kidney Int. 2017;91:937–947. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuchshuber A, Jean G, Gribouval O, et al. Mapping a gene (SRN1) to chromosome 1q25–q31 in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome confirms a distinct entity of autosomal recessive nephrosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2155–2158. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters C, Rushton HG. Vesicoureteral reflux associated renal damage: congenital reflux nephropathy and acquired renal scarring. J Urol. 2010;184:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koike K, Ikezumi Y, Tsuboi N, et al. Glomerular density and volume in renal biopsy specimens of children with proteinuria relative to preterm birth and gestational age. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:585–590. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05650516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luyckx VA, Bertram JF, Brenner BM, Fall C, Hoy WE, Ozanne SE, Vikse BE. Effect of fetal and child health on kidney development and long-term risk of hypertension and kidney disease. Lancet. 2013;382:273–283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]