Abstract

Clonorchiasis, known as the Chinese liver fluke disease, is caused by Clonorchis sinensis infection with food-borne liver fluke, which is transmitted via snails to freshwater fish and then to human beings or other piscivorous mammals. Clonorchis sinensis infection is mainly related to liver and biliary disorders, especially cholangiocarcinoma, and has an increased human-health impact due to the greater consumption of raw freshwater fish. In this article, we propose a deterministic model to describe the spread of clonorchiasis among human-snail-fish populations and use the model to simulate the data on the numbers of inspected and infected individuals of Foshan City, located in Guangdong Province in the southeast of P.R China, from 1980–2010. Mathematical and numerical analyses of the model are carried out to understand the transmission dynamics of clonorchiasis and explore effective control measures for the local outbreaks of the disease. We find that (i) the transmission of clonorchiasis from cercariae to fish plays a more important role than that from eggs to snails and from fish to humans; (ii) As the cycle of infection-treatment-reinfection continues, it is unlikely that treatment with drugs alone can control and eventually eradicate clonorchiasis. These strongly suggest that a more comprehensive approach needs to include environmental modification in order to break the cercariae-fish transmission cycle, to enhance awareness about the disease, and to improve prevention measures.

Introduction

Clonorchiasis or Chinese liver fluke disease is a major food-borne parasitosis and caused by Clonorchis sinensis (C. sinensis) that parasitizes in the human intrahepatic bile duct1,2. It was first reported in 1875 by McConnell3 who observed a new species of liver fluke in the bile ducts of a patient during autopsy4 and the causative agent was identified as C. sinensis. Caused by the ingestion of raw or undercooked freshwater fish contaminated with the parasite C. sinensis, it is a food-borne zoonosis5. It is implicated in a wide spectrum of hepatobiliary diseases ranging from asymptomatic infection to more severe liver diseases including cholangitis or portal hypertension5. Recent evidences suggest that cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is the most severe complication of liver fluke infection and C. sinensis infection is classified as “carcinogenic to humans” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 20096. Meta-analysis and systematic reviews show pooled odds ratios for C. sinensis infection and cholangiocarcinoma ranging between 4.5 and 6.17,8. It was estimated that more than 601 million people were at the risk of C. sinensis infection and at least 35 million cases of clonorchiasis worldwide, contributing to approximately 5600 deaths in 20055,9. The overwhelming majority of clonorchiasis cases occur in endemic areas in eastern Asia, including Korea Peninsula, Japan, China, etc.7,8,10. Particularly, China has the biggest share with an estimated 13 million people infected with clonorchiasis3. Zhou et al.11 reported that the trend of infection risk is increasing from 2005 onwards and resulted in a threat to the public health in epidemic regions12,13. Specially, they estimated that around 14.8 million people in China were infected with C. sinensis in 201011 and there are two major endemic regions in China: provinces in the northeast such as Heilongjiang and Jilin; and provinces in the southeast including Guangdong and Guangxi8,14.

C. sinensis is characterised by an alternation of sexual and asexual reproduction in different hosts15,16, involving three intermediate hosts including freshwater snails (act as the first intermediate hosts), occasionally shrimps and freshwater fish (act as the second intermediate hosts), and humans or carnivorous mammals (act as the definitive hosts)3,5,17. Simply speaking, eggs laid by hermaphroditic adult worms reach the intestine with bile fluids and are eliminated with the faeces18. Subsequently, freshwater snails swallow the eggs19, through asexual reproduction, sporocysts, rediae, and then cercariae are produced. After escaping from the snails, cercariae then infect and adhere to freshwater fish20 and develop into mature metacercariae. When people or other piscivorous mammals eat insufficiently cooked or raw infected fish, they will become the definitive hosts3,9. Patients with low infection intensity are often show only mild symptoms or asymptomatic or even without any performance, whereas patients with high infection intensity often show unspecific symptoms, such as indigestion, asthenia, nausea, vertigo, dizziness, headache, abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain, or diarrhoea, especially in the right upper quadrant3. Typical physical signs of C. sinensis infection are liver tenderness, jaundice and hepatomegaly3.

In recent years, clonorchiasis has been studied from many different perspectives, including epidemiological features3, key clinica, geography, diagnostic, immunology, etc. Qian et al.10 presented comparisons between clonorchiasis and hepatitis B in terms of carcinogenicity, disability and epidemiology, clinical symptoms as well as changing trends. Lai et al.11 carried out Bayesian variable selections to identify the most important predictors of C. sinensis risk and their results provide spatially relevant information for guiding clonorchiasis control interventions in China. Specially, researchers have obtained some protective effects about vaccine, but only in rat models21–23. Though clonorchiasis has been studied for more than 140 years and we have a sound understanding of clonorchiasis, but there has been no study using mathematical modelling approach to assess different tools and strategies for the control of clonorchiasis. However, many researchers have studied vector-borne diseases that have only one main intermediate host24–28. The results in25,26 showed that control strategies that target on the transmission of schistosomiasis from the snail to man will be more effective than those that block the transmission from man to snail. Particularly, Chiyaka et al.25 constructed a deterministic mathematical model of schistosomiasis where the miracidia and cercariae dynamics are incorporated.

To understand the transmission dynamics of clonorchiasis and to explore effective control and prevention measures, in this paper we propose a deterministic model for the human-snail-fish transmission of clonorchiasis. The aim is to use mathematical modeling approach to gain some insights into the transmission dynamics of clonorchiasis in these populations. The model is a system described by ten ordinary differential equations counting for susceptible and infected human, snail, fish subpopulations, recovered people, exposed people, egg and cercaria. We study the basic properties of the model, including the boundedness of solutions, existence and stability of the disease-free equilibrium and the endemic equilibrium. Then, to validate the model, we use the model to simulate the data on the numbers of inspected and infected individuals in Foshan City, Guangdong Province, China, from 1980 to 2010. Specially, it should be pointed out that we regard the number of inspected persons as the number of exposed individuals. Numerical simulations match the data reasonably well. We also give some reasonable predictions for Foshan City for the coming years. Finally, by carrying out sensitivity analysis of the basic reproduction number R0 in terms of model parameters, we try to explore some strategies to prevent and control the local infection of clonorchiasis.

The remaining part of this paper is organized as follows. In section 2, we formulate a mathematical model to describe the spread of clonorchiasis among snail, fish and human populations. We calculate the basic reproductive number of the model, discuss the global stability of the disease-free equilibrium and the endemic equilibrium in Section 3. Data simulations and sensitivity analysis of R0 on model parameters are carried out in Section 4. A brief discussion and various control measures are given in Section 5.

Methods

In this section, we present a mathematical model to study the transmission dynamics of clonorchiasis among human, snail and fish populations. The model is based on a susceptible, exposed, infectious, and recovered (SEIR) structure and explains the transmission process among humans, snails and fish.

The Model

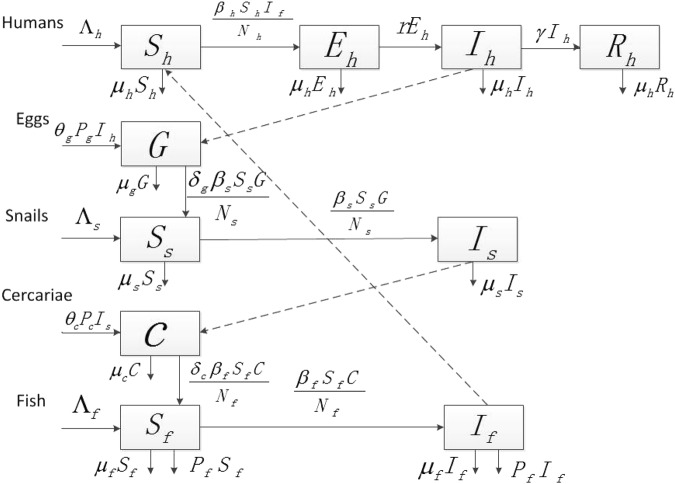

Let Sh(t), Eh(t), Ih(t) and Rh(t) denote the number of susceptible, exposed, infectious, and recovered humans at time t, respectively. Similarly, Ss(t), Is(t), Sf(t) and If(t) represent the number of susceptible and infectious snails/fish at time t, respectively. Let G(t) and C(t) be the population of eggs and cercariae, respectively. Here the total human population is denoted by Nh(t) = Sh(t) + Eh(t) + Ih(t) + Rh(t). Meanwhile, Ns(t) = Ss(t) + Is(t) and Nf(t) = Sf(t) + If(t) are the total numbers of snails and fish. Our assumptions are given in the flowchart (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the clonorchiasis model for the transmission of clonorchiasis among human, snail and fish populations.

Considering an infected individual, a portion Pg of eggs leave the infectious body with the faeces or urine and at a rate of θg find their way into the fresh water. The infected snails will then release a second form of free swimming larva called a cercaria, a portion Pc, at a rate θc.

For other parameters, those Λi(i = h, s, f) are the recruitment rates of humans, snails and fish, respectively. βi(i = h, s, f) are the transmission rates of clonorchiasis from fish to humans, eggs to snails, and cercariae to fish. δg and δc refer to as per consumption coefficient of the eggs by snails and those of the cercariae by fish, respectively. γ describes the recovery rate. is the average period of latency. All those labelled μi(i = h, s, f, g, c) are defined as the natural death rates of humans, snails, fish, eggs and cercariae. The predation rate of fish is p.

The number of eggs consumed by snails compared to the number of eggs in the environment is very small. Thus, the deletion by snails from the egg population can be ignored. Similarly, the deletion by fish from the cercaria population can be ignored, too.

Based on the assumptions and the flowchart, our model is consisted of the following equations:

| 1 |

under the initial value conditions Sh(0) ≥ 0, Eh(0) ≥ 0, Ih(0) ≥ 0, Rh(0) ≥ 0, G(0) ≥ 0, Ss(0) ≥ 0, Is(0) ≥ 0, C(0) ≥ 0, Sf(0) ≥ 0, If(0) ≥ 0. All parameters are nonnegative constants with their biological interpretations given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of model parameters (PRM) and their values (unit: year−1).

| PRM | Value | Interpretation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Λh | 5 × 104 | Recruitment rate of susceptible humans | fitting |

| Λs | 3.12 × 106 | Recruitment rate of susceptible snails | fitting |

| Λf | 1 × 103 | Recruitment rate of susceptible fish | fitting |

| β h | 9.69 × 10−2 | Transmission rate from infected fish to human | fitting |

| β s | 5.54 × 10−4 | Transmission rate from egg to snail | fitting |

| β f | 3.59 × 10−3 | Transmission rate from cercaria to fish | fitting |

| μ h | 1.4 × 10−2 | Death rate of human hosts | 26 |

| μ s | 1 | Death rate of snails | 24, 31 |

| μf + p | 0.3031 | Death rate and predation rate of fish | fitting |

| μ g | 3.85 × 10−2 | Death rate of eggs | 3 |

| μ c | 2.614 | Death rate of cercariae | 3 |

| P c | 452 | Number of cercariae in every infected snail | fitting |

| P g | 1.46 × 106 | Number of embryonated eggs passed by each infected human | 3 |

| θ g | 1 × 10−2 | Rate of eggs into the fresh water (snail) | fitting |

| θ c | 0.1564 | Rate of cercariae released from infected snails | fitting |

| γ | 0.73 | Per capita recovery rate of human hosts | 32 |

| r | 0.2405 | Transmission rate from exposed to infectious human | fitting |

Specific parameter values will be given in section 4 when the model is used to fit the data of inspected and infected individuals of Foshan City from29. Notice that the clonorchiasis data reported by29 are annual data. In order to use model (1) to simulate the annual clonorchiasis data from29, we use a percentage per year to describe some parameters so that the time unit is year. For example, μs = 1/year means that the average life of snails is 12 months.

The Basic Reproduction Number

Each of the total subpopulations Nh(t), Ns(t), Nf(t), G(t) and C(t) is assumed to be nonnegative at t = 0. Using standard analysis we know that all solutions to system (1) are nonnegative. The region

is positively invariant for system (1).

Model (1) has a disease-free equilibrium given by

Following the methods and results in Diekmann et al.18 and van den Driessche and Watmough30, we define the basic reproduction number as

| 2 |

Moreover, if R0 < 1 the disease-free equilibrium E0 of system (1) is locally asymptotically stable; if R0 > 1 then E0 is unstable and a positive endemic equilibrium

exists, where

Furthermore, if R0 > 1 the endemic equilibrium E* of system (1) is locally asymptotically stable in the region Ω. The statements and proofs of these results are given in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

Results

Data from Foshan City

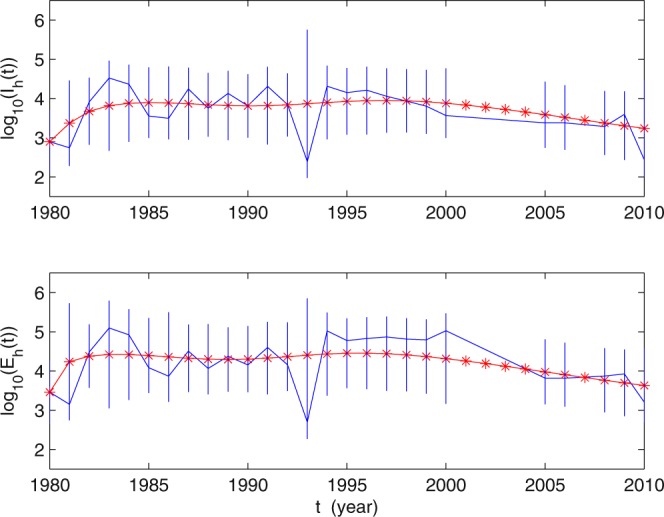

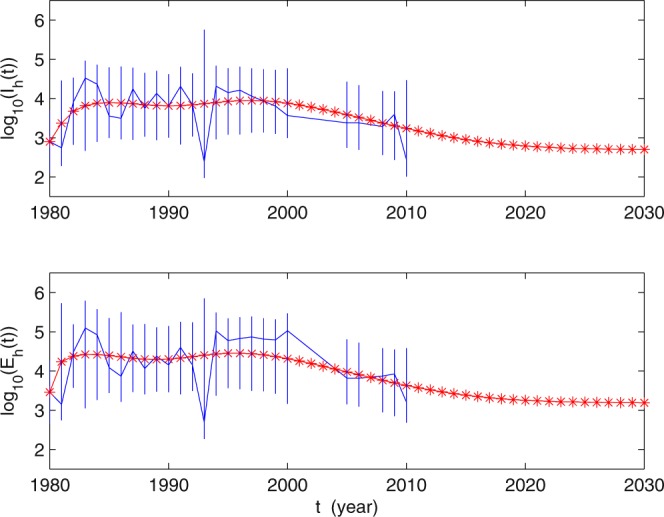

Foshan City in Guangdong Province, China, was selected as the simulating area, based on the following reasons. First, Guangdong Province, extending from the Pearl and Han rivers, has the highest prevalence of C. sinensis9. Second, Foshan City ranks among the top infection areas in Guangdong due to the special diet habits of local people29. Third, some villages of Foshan City (Shibo in Shunde district) have not yet received mass drug administration22. In this section, we first use model (1) to simulate the data on the numbers of inspected and infected humans of Foshan City from 1980 to 2010 provided by29. The numbers of inspected and infected individuals are of the order of magnitude of 1 × 102 to 1 × 106, which is uneasy to do numerical fitting. So we turn the data into a base 10 logarithm. In other words, we substitute log10 (Eh(t)) and log10 (Ih(t)) for the numbers of inspected and infectious of humans. From 1980–2010, the values of log10 (Eh(t)) and log10 (Ih(t)) are shown in Table 2, where ‘−’ means that there is no survey data in that year. Numerical simulations of log10 (Eh(t)) and log10 (Ih(t)) are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

The values of log10 (E(t)) and log10 (I(t)).

| Year | log10 (E(t)) | log10 (I(t)) | Year | log10 (E(t)) | log10 (I(t)) | Year | log10 (E(t)) | log10 (I(t)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 3.4597 | 2.8976 | 1991 | 4.5999 | 4.3089 | 2002 | — | — |

| 1981 | 3.1511 | 2.7412 | 1992 | 4.158 | 3.8479 | 2003 | — | — |

| 1982 | 4.4816 | 3.9132 | 1993 | 2.6972 | 2.3909 | 2004 | — | — |

| 1983 | 5.0955 | 4.5209 | 1994 | 5.0207 | 4.3112 | 2005 | 3.8152 | 3.378 |

| 1984 | 4.9212 | 4.3606 | 1995 | 4.7746 | 4.1487 | 2006 | 3.8152 | 3.378 |

| 1985 | 4.0817 | 3.5541 | 1996 | 4.8266 | 4.2094 | 2007 | — | — |

| 1986 | 3.8653 | 3.4935 | 1997 | 4.8647 | 4.0579 | 2008 | 3.8717 | 3.2851 |

| 1987 | 4.5069 | 4.2427 | 1998 | 4.8128 | 3.9335 | 2009 | 3.9236 | 3.5933 |

| 1988 | 4.0626 | 3.7496 | 1999 | 4.7943 | 3.806 | 2010 | 3.202 | 2.4362 |

| 1989 | 4.3759 | 4.1305 | 2000 | 5.0238 | 3.5641 | |||

| 1990 | 4.1538 | 3.8127 | 2001 | — | — |

Figure 2.

The solid blue curves represent the values of log10 (E(t)) and log10 (I(t)), where the data of E(t) and I(t) are reported in29. The solid red curves are simulated by using the model (1), the vertical segments are shown the 95% confidence intervals of the values of log10 (E(t)) and log10 (I(t)). The values of parameters are given in Table 1. The initial values used in the simulations are given in Table 3.

Estimation of Parameters

In order to carry out the numerical simulations, we need to estimate the model parameters. We obtain these parameter values using two approaches: some parameter values are adapted from literature; and some other parameter values are estimated by the MATLAB tool fminsearch, which is estimated by calculating the minimum sum of square (MSS):

where ni = 1980, 2005, 2008, Ni = 2000, 2006, 2010, i = 1, 2, 3. All parameter values for Foshan City are given in Table 1. Next, we explain the parameter values as follows: (a) we fixed the natural death rates of humans and snails as , , and , respectively, from the assumption that the average life lengths of humans, snails, eggs and cercariae are about 72 years26, 1 year24,31, 26 years3, and 140 days3, respectively. For infected human, the egg-laying capacity is estimated at around 4000 eggs per worm per day3, then we can estimate Pg = 4000 × 365 = 1.46 × 106/year. Per capita recovery rate of human hosts is γ = 0.7332. We obtained Eh(0) = 2882, Ih(0) = 790 from29 and Rh(0) = Ih(0) × γ = 568. (b) Λh, Λs, Λf and other initial values, which are shown in Table 3, were regarded as parameters. The transmission rates βh and βf, the released rate of cercaria from every infected snail θc are obtained by fitting in simulations and the same as r, p + μf, Λh, Λs, Λf. By the parameter values in Table 1, we can estimate that the basic reproduction number of human clonorchiasis is R0 = 2.01.

Table 3.

Initial conditions (INC) of system (1).

Applications to the C. sinensis infections in Foshan City

Using these parameter values, we carry out numerical simulations of our model and obtain a reasonable match in Fig. 2, indicating that our model provides a good match to the reported data. We would like to mention that from 1990–2010, integrated control strategies, including environmental management, repeated examination, education and capacity building through intersectoral collaboration, were advocated in Guangdong Province29. The awareness of the liver fluke disease for people from 1990 has been enhanced gradually, especially from 1994–2000. Particularly, inspection work in Collective-Owned group was carried out in Foshan City from 1997–200029. This may explain why the number of infectious persons decreased and more people were inspected than in the previous years from 1994–2000. The model does not include these measures. While when the number of infectious humans is decreasing, people may not have the consciousness of this disease, so the number of inspected people may decrease again from 2000. This demonstrates further that our model has certain rationality. Figure 3 presents the tendency of clonorchiasis disease epidemics under the current control strategies and of the 95% confidence intervals. The result shows that the number of human clonorchiasis cases will decrease steadily in the future and finally becomes stable. This means that if no further effective prevention and control measures are taken, the disease will be epidemic in Foshan City.

Figure 3.

The tendencies of the values log10 (E(t)) and log10 (I(t)).

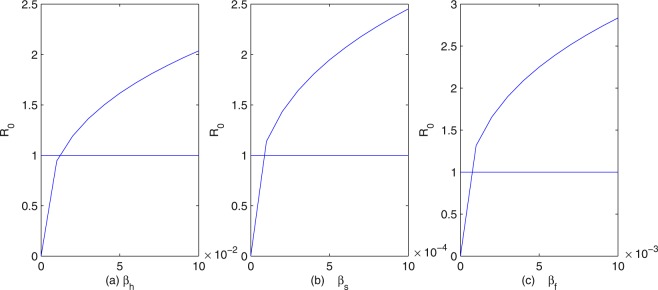

Sensitivity analysis

To provide some effective control measures about clonorchiasis, we perform some sensitivity analysis of the basic reproduction number R0 in terms of our model parameters. From Fig. 4, we can see that the influence of fish on R0 is greater than humans and snails. In fact, if we fix all the parameters except βs, βf, βh, then R0 increases as any of the transmission coefficients increases. However, R0 increases more rapidly as the transmission coefficient from cercariae to fish βf increases than from fish to humans βh and from eggs to snails βs. Thus, we know that the transmission of clonorchiasis from cercariae to fish plays a more important role than that from eggs to snails and from fish to humans. This strongly suggests that a more comprehensive approach needs to include environmental modification in order to break the cercaria-fish transmission cycle. In Fig. 4(a), R0 increases as βh increases. Hence, the practical measure for preventing and controlling human infection is to reduce and stop the consumption of undercooked, freshly pickled or raw fish and shrimp flesh, making a decrease of βh. There is evidence showing that human beings can become infected via the accidental ingestion of C. sinensis metacercariae via their hands, contaminated as a consequence of not washing after catching freshwater fish7, then more attention should be paid to the safety of freshwater fish17. In addition, metacercaria-tainted fish should be barred from markets.

Figure 4.

The dependence of R0 on (a) βh; (b) βs; (c) βf.

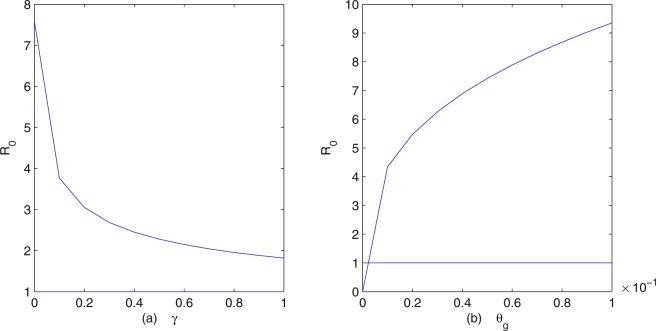

Figure 5(a) shows the dependence of the basic reproduction number R0 on the recovery rate of human hosts γ, indicating that R0 decreases as γ increases. The disease cannot be eliminated even if γ = 1, which indicates that treatment with drugs alone is insufficient to achieve the complete control of clonorchiasis. As a matter of fact, residents in the epidemic areas find it is difficult to change their habit of eating raw fish and they have more opportunities to ingest food containing raw fish. For instance, in south China (for example Guangdong) and parts of east Asia, various species of carp, particularly C. idellus (grass carp), eaten raw as a “yusheng zhou” or as a “sushi”-fish congee, dipped in hot rice soup, are considered delicacies9. The sustainability of achievements in the long run is challenging, as the cycle of infection-treatment-reinfection continues, especially in the older age groups33. From Fig. 5(b) we see that R0 increases as the rate of eggs into the fresh water (snails) θg increases. This means that environmental modification is an important method of controlling clonorchiasis, such as removing unimproved lavatories built adjacent to fish ponds in endemic areas, thus preventing water contamination by faeces9,11. Removing pigsties and toilets from fishpond areas is an important step to decrease the source of eggs17, which is helpful in the field of environmental reconstruction. Furthermore, it is strongly necessary to inform farmers not to use human faeces as fertilizer, this breeding and cultivation practice can increase the risk of clonorchiasis infection because the faeces are highly saturated with C. sinensis eggs1.

Figure 5.

The dependence of R0 on (a) γ; (b) θg.

Discussion

Recognized as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization for decades, clonorchiasis remains prevalent worldwide, although control programmes and some chemotherapy have been implemented over several years in some endemic areas. Clinical and epidemiological research into clonorchiasis over the past 140 years has contributed to a deeper understanding of the parasite, intermediate hosts, and disease3. Many interesting articles have also been published to investigate the prevention and control measures of the diseases, see6,18,19,24,26. Most of these studies focus on the pathology, biology, the discovery of new diagnostic, drug, and vaccine targets. Until now there is no study using mathematical models to assess different tools and strategies for large-scale control of clonorchiasis.

In this paper, we have proposed a deterministic model to describe the human-snail-fish transmission of clonorchiasis and studied its dynamical behavior. Meanwhile, our model can help in examining the current control and prevention policies. By estimating the parameter values, we obtianed R0 = 2.01, used the model to simulate the human clonorchiasis data from Foshan City reported in29, and predicted the spread of the disease in the city for the near future. We believe that it is the first time the human clonorchiasis data from Foshan City have been systematically simulated by using mathematical models. These numerical simulations indicate that the clonorchiasis disease has not reached its equilibrium yet and will become endemic in the future, which means that current control and prevention strategies cannot guarantee the eradication of the disease.

In order to find out effective control measures to prevent outbreaks of clonorchiasis in Foshan City, we performed various numerical simulations of our model. Figure 4 suggests that, to control and eventually eradicate clonorchiasis, a more comprehensive approach needs to include environmental factors3 in order to break the cercaria-fish transmission cycle. The infection rates and distributions of freshwater fish and snails should be investigated in endemic areas. These control measures include more comprehensive surveillance on fish, early check and vaccination of fish, and snail control by means of environment management. Indeed, an oral vaccine based on B subtilis expressing enolase is under test in freshwater fish34. Biological control, with predator fish that feed on snails, needs further investigation35. Figure 5(a) indicates that only by treatment with drugs cannot control and eventually eradicate C. sinensis. Today, praziquantel is the recommended drug of choice and tribendimidine might be an alternative36. But, cure rates were low, especially in the treatment of heavy infections37 and the cycle of infection-treatment-reinfection continues. Given the indirect economic losses and direct medical issues associated with clonorchiasis infection, there is a need for multifaceted prevention programs in addition to treatment with drugs. However, no commercially produced or effective vaccine is available for the treatment of clonorchiasis infection in humans or other hosts as of yet17. Researchers have obtained some protective actions, but only in rat models21,23.

There are some limitations in our study. Firstly, host heterogeneity was not included in the model, while different human groups may have different transmission patterns and different infection rates38. For example, males certainly have a higher infection rate than females. Secondly, the data we used were limited. Third, piscivorous animals, especially dogs and cats (both reared or wild as guardians or pets), serve as reservoir hosts for C. sinensis, and these animals are widely distributed34,39, but were not considered in this paper.

In conclusion, a combination of control strategies consisted of education, information and communication, treatment, environmental management, and preventive chemotherapy should be advocated for controlling the disease and preventing large local outbreaks.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which lead to a significant improvement of the quality and presentation of the manuscript. This research was partially supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 11771168, No. 11871238, No. 11871235, No. 11471133).

Author Contributions

R.Y., J.H., X.Z. and S.R. designed the study. R.Y. analyzed the model, collected the data and performed the simulations. R.Y., J.H. and S.R. developed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xinan Zhang, Email: xinanzhang@mail.ccnu.edu.cn.

Shigui Ruan, Email: ruan@math.miami.edu.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-33431-w.

References

- 1.Li T, Yang Z, Wang M. Correlation between clonorchiasis incidences and climatic factors in Guangzhou, China. Parasit. Vectors. 2014;7:29. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qian M. Clonorchiasis control: starting from awareness. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2014;3:33. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qian M, Utzinger J, Keiser J, Zhou X. Clonorchiasis. Lancet. 2016;387:800–810. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauss W. Clonorchiasis in San Francisco. JAMA. 1962;179:290. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050040044013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gowda C. Recognizing clonorchiasis: a foodborne illness leading to significant hepatobiliary disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2015;6:44–46. doi: 10.1002/cld.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouvard V, et al. A review of human carcinogens–Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–322. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fürst T, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Global burden of human food-borne trematodiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012;12:210–221. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian M, Chen Y, Song L, Yang G, Zhou X. The global epidemiology of clonorchiasis and its relation with cholangiocarcinoma. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2012;1:4. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lun Z, et al. Clonorchiasis: a key foodborne zoonosis in China. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005;5:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian M, Chen Y, Yan F. Time to tackle clonorchiasis in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2013;2:4. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai Y, Zhou X, Pan Z, Utzinger J, Vounatsou P. Risk mapping of clonorchiasis in the People’s Republic of China: a systematic review and Bayesian geostatistical analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11:e0005239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keiser J, Utzinger J. Emerging foodborne trematodiasis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:1507–1514. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. Working to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases: First WHO Report on Neglected Tropical Diseases (Geneva, Switzerland, WHO, 2010).

- 14.Fang Y, Cheng Y, Wu, Zhang JQ, Ruan C. Current prevalence of Clonorchis sinensis infection in endemic areas of China. Chinese J. Parasitol. Parasit. Dis. 2008;26:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keiser J, Utzinger J. Food-borne trematodiases. Clin. MicrobioL. Rev. 2009;22:466–483. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00012-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Intapan P, Maleewong W, Brindley P. Food-borne trematodiases in Southeast Asia: epidemiology, pathology, clinical manifestation and control. Adv. Parasitol. 2010;72:305–350. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(10)72011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang Z, Huang Y, Yu X. Current status and perspectives of Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, omics, prevention and control. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2016;5:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0099-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek J, Metz J. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio & in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 1990;28:365–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00178324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsü H, Li S. Studies on certain problems of Clonorchis sinensis IX. The migration route of its early larval stages in the snail, Bithynia fuchsiana. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 1940;3:244–254. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang C, et al. Experimental establishment of life cycle of Clonorchis sinensis. Chin. J. Parasitol. Parasit. Dis. 2009;27:148–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen T, et al. Advanced enzymology, expression profile and immune response of Clonorchis sinensis hexokinase show its application potential for prevention and control of clonorchiasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0003641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian M, et al. Disability weight of Clonorchis sinensis infection: captured from community study and model simulation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011;5:e1377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, et al. Surface display of Clonorchis sinensis, enolase on bacillus subtilis, spores potentializes an oral vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2014;32:1338–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, Zou L, Zhang W, Shen D, Ruan S. Mathematical modelling and control of schistosomiasis in Hubei Province, China. Acta Trop. 2010;115:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiyaka E, Garira W. Mathematical analysis of the transmission dynamfics of schistosomiasis in the human-snail hosts. J. Biol. Syst. 2009;17:397–423. doi: 10.1142/S0218339009002910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao S, Liu Y, Luo Y, Xie D. Control problems of a mathematical model for schistosomiasis transmission dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 2011;63:503–512. doi: 10.1007/s11071-010-9818-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang S, et al. Environmental effects on parasitic disease teansmission exemplified by schistosomiasis in western China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7110–7115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701878104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.May R. Togetherness among schistosomes: its effects on the dynamics of the infection. Math. Biosci. 1977;35:301–343. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(77)90030-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guan Q, Huang Z. The liver fluke disease infection status and the analysis of epidemiological characteristics of Foshan from 1980–2010. South China J. Prev. Med. 2015;41:276–279. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Den Driessche P, Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002;180:29–48. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spear R, Hubbard A, Liang S, Seto E. Disease transmission models for public health decision making: toward an approach for designing intervention strategies for schistosomiasis japonica. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110:907–915. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng Z, Fang Y. Epidemic situation and prevention and control strategy of clonorchiasis in Guangdong Province, China. Chin. J. Schisto. Control. 2016;28:229–233. doi: 10.16250/j.32.1374.2016081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziegler AD, Andrews RH, Grundy-Warr C, Sithithaworn P, Petney TN. Fighting liverflukes with food safety education. Science. 2011;331:282–283. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6015.282-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen T, et al. Prevalence and risks for fishborne zoonotic trematode infections in domestic animals in a highly endemic area of North Vietnam. Acta Trop. 2009;112:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hung N, Duc N, Stauffer JR, Jr., Madsen H. Use of black carp (mylopharyngodon piceus) in biological control of intermediate host snails of fish-borne zoonotic trematodes in nursery ponds in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Parasit. Vectors. 2013;6:142. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO. Sustaining the Drive to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases: Second WHO Report on Neglected Tropical Diseases (Geneva, Switzerland, WHO, 2013).

- 37.Qian M, et al. Efficacy and safety of tribendimidine against Clonorchis sinensis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;56:e76–e82. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang W, Wu N, Liao Z, Liang ZM. Analysis of Clonorchiasis Sinensis in Foshan in different age and sex groups distribution. J. Med. Pest Control. 2010;26:48–49. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin R, et al. Prevalence of Clonorchis sinensis infection in dogs and cats in subtropical southern China. Parasit. Vectors. 2011;4:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.