Abstract

Although the glucose lowering effect of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors is well established, several potential serious acute safety concerns have been raised including acute kidney injury, respiratory tract infections, and acute pancreatitis. Using the UK-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), we identified initiators (365-day washout period) of DPP4 inhibitors and relevant comparators including initiators of sulfonylureas, metformin, thiazolidinediones, and insulin between January 2007 and January 2016 to quantify the association between DPP4 inhibitors and three acute health events – acute kidney injury, respiratory tract infections, and acute pancreatitis. The associations between drug and study outcomes were estimated using Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for deciles of high-dimensional propensity scores and number of additional glucose lowering agents. After controlling for potential confounders, the risk was not significantly increased or decreased for initiators of DPP4 inhibitors compared to sulfonylureas (hazard ratio (HR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] for acute kidney injury: 0.81 [0.56–1.18]; HR for respiratory tract infections: 0.93 [0.84–1.04]; HR for acute pancreatitis 1.03 [0.42–2.52], metformin (HR for respiratory tract infection 0.91 [0.65–1.27]), thiazolidinediones (HR for acute kidney injury: 1.12 [0.60–2.10]; HR for respiratory tract infections: 1.02 [0.86–1.21]; HR for acute pancreatitis: 1.21 [0.25–5.72]), or insulin (HR for acute kidney injury: 1.40 [0.77–2.55]; HR for respiratory tract infections: 0.74 [0.60–0.92]; HR for acute pancreatitis: 1.01 [0.24–4.19]). Initiators of DPP4 inhibitors were associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury when compared to metformin initiators (HR [95% CI] for acute kidney injury: 1.85 [1.10–3.12], although this association was attenuated when DPP4 inhibitor monotherapy was compared to metformin monotherapy exposure as a time-dependent variable (HR 1.39 [0.91–2.11]). Initiation of a DPP4 inhibitor was not associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury, respiratory tract infections, or acute pancreatitis compared to sulfonylureas or other glucose-lowering therapies.

Introduction

The glucose-lowering effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors have been well documented since their introduction to the global market in the mid-2000’s. Their utilization for the management of glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes is increasing1–3. Despite beneficial glycemic effects, a low risk of hypoglycemia, and neutral effect on weight, there is a lack of evidence suggesting any mortality or morbidity benefits for patients using DPP4 inhibitors4,5. Moreover, several potential acute effects of DPP4 inhibitors have been generated from pre-marketing and post-marketing data including clinical trials, pharmacovigilance databases, and observational studies. These include health events such as acute kidney injury, respiratory tract infections, and acute pancreatitis.

It is unclear whether DPP4 inhibitors play a role in the development of diabetic kidney disease. DPP4 inhibitors prolong the half-life of glucagon-like-peptide-1 (GLP-1), which in turn improves insulin secretion in response to oral glucose consumption and suppresses glucagon release, ultimately decreasing blood glucose levels. Given that the DPP4 enzyme is present in various components of the endothelial and epithelial kidney tissues (including renal proximal tubular epithelia, podocytes, mesangial cells, and pre-glomerular vascular smooth muscle cells), it has been hypothesized that DPP4 inhibitors will have a protective effect on the kidney by reducing inflammation and fibrosis and improving overall function6,7. However, other mechanisms may be responsible for acute changes in renal function including fluid depletion and volume contraction via vomiting and diarrhea, although evidence exists suggesting a beneficial effect of natriuretic and diuretic properties of DPP4 inhibitors8,9. Findings from observational studies have been inconsistent. A nested case-control study of over 7000 patients in Taiwan found that individuals who had taken a DPP4 inhibitor in the last 365 days were more likely to develop acute kidney injury (OR = 1.2; 95% CI 1.11–1.37)10. Sub-group analysis showed this increased risk was primarily in individuals who had taken a DPP4 inhibitor in the last 30 days. A recent cohort study, also using a Taiwanese database, included 923,936 patients with diabetes, 83,638 of which were users of a DPP4 inhibitor. After an average of 3.6 years of follow-up, DPP4 inhibitors users had a significantly lower risk of acute kidney injury (HR = 0.57; 95% CI 0.53–0.61) and acute kidney injury requiring dialysis (HR = 0.57; 95% CI 0.49–0.66)11. Another cohort study using administrative data sources in the United Kingdom and the United States, included 1,024,124 individuals, 110,740 exposed to the DPP-4 inhibitor saxagliptin. With follow-up time ranging from 5.6–8.1 months, this study found no increased risk of acute kidney injury (HR = 0.99; 95% CI 0.88–1.11)12.

There are several potential mechanisms that may be responsible for immune-related effects of DPP4 inhibitors. Biologically, DPP4 has immune modulatory effects on cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammatory cytokines13. Since the enzyme DPP4 is structurally similar to the lymphocyte protein CD26, there is a concern that DPP4 inhibitors may increase the risk of infections14,15. Spontaneous reporting of infections are two times higher in patients using DPP4 inhibitors compared to metformin, with reports of upper respiratory tract infections at 12 times higher13; however, there are significant limitations with spontaneous reporting and, due to underreporting of events, population-based incidence rates cannot be measured16. Results from pre-marketing clinical trials of DPP4 inhibitors are inconsistent with some drugs showing a potential increased dose-dependent risk of upper respiratory tract infections (e.g., sitagliptin 100 mg 11.4%, 200 mg 14.8%, placebo 7.1%) and other drugs showing no increased risk (e.g., saxagliptin)15. A recently published meta-analysis pooling these trials did not find a difference in the rate of respiratory tract infections between users of DPP4 inhibitors and other agents17; however, the included trials were of short duration and not designed to assess long-term safety. Recent observational studies have also failed to show any relationship between DPP4 inhibitors and community-acquired pneumonia18,19.

Concerns over an increased risk of acute pancreatitis with the DPP4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists have been raised based on case reports20–22. Some animal and post-mortem human studies suggest that activation of GLP-1 receptor on exocrine pancreatic cells can lead to their proliferation and possibly to inflammation23–25. However, a causal association between exposure to incretin-based medications and pancreatitis has not been established and both the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Association (EMA) have investigated the association thoroughly20,24,26. There is emerging evidence that ductal and pancreatic stellate cells of chronically inflamed pancreas express GLP-1 receptors that are not normally present in the cells of healthy pancreas27. This observation makes it possible for patients with pre-existing undiagnosed asymptomatic chronic pancreatitis to experience acute episodes after initiation of GLP-1 agonist or DPP4 inhibitor contributing to the increased incidence of acute pancreatitis in some studies. The findings from the majority of published observational studies (8 of 10) suggest that incretin-based medications do not increase the risk of acute pancreatitis, although the evidence is not unanimous28–37.

It is important that we continue to investigate the risk of serious acute events with these agents, especially given the susceptibility to impaired kidney function, infection38,39, and acute pancreatitis. Furthermore, there is limited evidence evaluating the association between DPP4 inhibitors and acute outcomes, notably acute kidney injury and respiratory tract infections. Therefore, we conducted a series of population-based cohort studies to estimate the association between DPP4 inhibitors and these important acute outcomes.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) GOLD database was used to conduct a cohort study to estimate the risks of acute kidney injury, respiratory tract infections and acute pancreatitis in new users of DPP4 inhibitors compared to new users of glucose-lowering therapies with type 2 diabetes. The CPRD GOLD database contains longitudinal information from over 650 general practitioner practice sites across the United Kingdom, equating to about 7% of the total population and has been shown to be representative of the broader UK population40. It also contains a wide variety of patient information including sociodemographic data, physiological measures, laboratory data, clinician-assigned diagnoses, and outpatient prescription records. Data from the CPRD is subject to a rigorous quality check prior to being released for research purposes40. The source population for this study was derived based on the February 2016 CPRD GOLD dataset build. Furthermore, a subgroup of our source population (~58%) was linked to 3 additional databases: (a) Hospital Episode Statistics (HES – data available up to March 31, 2014) providing diagnostic and clinical information for hospital visits, (b) the Office of National Statistics (ONS – data available up to April 30, 2014) providing cause of death, and (c) the index of multiple deprivation (2010) providing an indicator for socioeconomic status.

The study population consisted of individuals whom 1) had filled a prescription for a glucose-lowering drug or had a diagnostic record for type 2 diabetes on or after January 1st, 2007 (index date), with no previous glucose-lowering prescription or diagnostic record within the previous 365 days (date of prescription/diagnostic record was set at the study entry date); 2) had up-to-standard medical history for a minimum of 12 months prior to study entry date; and 3) were 18 years of age or older at the study entry date. Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, pregnant women, and those with gestational diabetes were excluded. A series of study cohorts were established to examine the three primary outcomes of interest (herein referred to as the acute kidney injury cohort, respiratory tract infection cohort, and acute pancreatitis cohort). We applied specific exclusion criteria based on pre-existing comorbidities, procedures, and prescription records (Supplemental material, Table S1). Moreover, separate study sub-cohorts were constructed for each exposure contrast of interest.

The study protocol was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC 15_016RARA, August 2017) and the Health Research Ethics Board at Memorial University (HREB #20140717).

Outcome and Exposure Definitions

Our primary outcomes of interest were time to the first diagnosis of either acute kidney injury, acute respiratory tract infection, or acute pancreatitis recorded during the study follow-up period in the respective cohort populations. Secondary outcomes included a breakdown of the types of acute respiratory infections (i.e., upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia and influenza) within the respiratory tract infections cohort. Outcomes were defined based on READ codes contained in the CPRD data and ICD-10 codes in the HES data (see Supplementary Appendix Tables S2–S7 for list of diagnostic codes).

We defined exposure status in a consistent manner across all study sub-cohorts of interest. Sub-cohorts of interest were constructed based on exposure contrasts of interest that were defined a priori including a) DPP4 inhibitor vs. sulfonylurea, b) DPP4 inhibitor vs. metformin, c) DPP4 inhibitor vs. thiazolidinedione, d) DPP 4 inhibitor vs. insulin. Exposure status was defined as initiation (based off first time use with a 365-day washout period) of one of the following medication classes: 1) DPP4 inhibitors, 2) Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, 3) Sulfonylureas, 4) Metformin, 5) Thiazolidinediones, 6) Sodium glucose co-transptor-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, 7) Meglitinides, 8) Acarbose, 9) Insulin, 10) diet/lifestyle management (no anti-diabetic medications). Person-time was accumulated in each of the exposure categories starting on the sub-cohort entry date. Censoring occurred once they discontinued the medication, received a prescription for a comparator medication, left the CPRD participating practice, died or on the last day of documented follow-up, whichever occurred first. To account for potential non-adherence, we applied 50% of the supplied number of days to the end of each prescription.

Statistical Analysis

New initiators of DPP4 inhibitors were compared against sulfonylureas, metformin, thiazolidinediones, and insulin as active comparators within separate sub-cohorts. Sulfonylureas were pre-specified as our primary reference group and other glucose-lowering agents (e.g., SGLT-2 inhibitors) were used too infrequently to conduct any meaningful analysis. Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards regression analysis was used to estimate the independent association between use of a DPP4 inhibitor and the risk of acute kidney injury, respiratory tract infections and acute pancreatitis, after adjusting for several potential confounding variables. We used high-dimensional propensity scores (hdPS) to adjust for potential confounding whereby we selected a set of 40 covariates, for each of the outcomes, from hundreds of potential confounders through an empirical, multi-step process41. Propensity scores for DPP4 inhibitors and comparators (separate models were run for each exposure contrast of interest) were estimated using multivariable logistic regression, whereby 40 covariates were identified through the hdPS procedure and several pre-defined covariates measured within the 365 days prior to the index date. Pre-defined covariates (Supplementary Appendix Table S8) included age, sex, smoking status, socioeconomic status, year of cohort entry, alcohol abuse, body mass index, duration of diabetes, history of cirrhosis, heart failure, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, number of hospitalizations, number of distinct prescription drugs, most recent HbA1c value, as well as outcome specific covariates (e.g. prior use of ACE inhibitors for acute kidney injury; prior use of antibiotics for respiratory tract infection; and prior use of fibrates for acute pancreatitis). Covariates included in the final Cox Proportional Hazards model included deciles of the propensity scores, as well as a categorical variable indicating the number of glucose-lowering agents an individual was exposed to during follow-up (1, 2, or 3+). Models assumptions (i.e. proportional hazards assumption) were tested using standard diagnostics based on weighted residuals42.Our power calculation was based on the method of Schoenfeld, which is designed for censored outcome data. Power calculations were conducted a priori using Stata/MT 13.1 (command stpower cox) with a type 1 error rate of 5% and used feasibility counts from CPRD for number of exposed and unexposed patients. Assuming a 0.1% event rate28 [expected rate of acute pancreatitis which was the least frequent outcome] over a median of 1-year follow-up there was 72% power to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.8 or smaller or 1.2 and greater.

We conducted additional subgroup and sensitivity analyses. First, we repeated the main analysis for acute kidney injury using a sub-group of patients with in-hospital events only. Second, a sub-group analysis based on location of respiratory tract infection was conducted including upper respiratory tract and lower respiratory tract (pneumonia/influenza). Third, we controlled for confounding by repeating the main analysis using a cohort of patients that were matched 1:1 based on their propensity score. A greedy nearest neighbor approach was used, and patients were selected in random order with a matching caliper set to 0.2 times the standard deviation of the natural logarithm of the propensity score. Fourth, we repeated the main analysis using a restricted cohort of patients that could be linked to hospitalization records. Fifth, we repeated our main analysis using alternative definitions of drug exposure including restricting to monotherapy users, add-on to metformin monotherapy users, and categorizing DPP4 inhibitors and comparators as time-dependent variables throughout follow-up. Lastly, we conducted an analysis whereby patients were grouped with others who had identical ordering of exposure to other glucose-lowering medication classes43. All analyses were conducted with R version 3.3.3.

Results

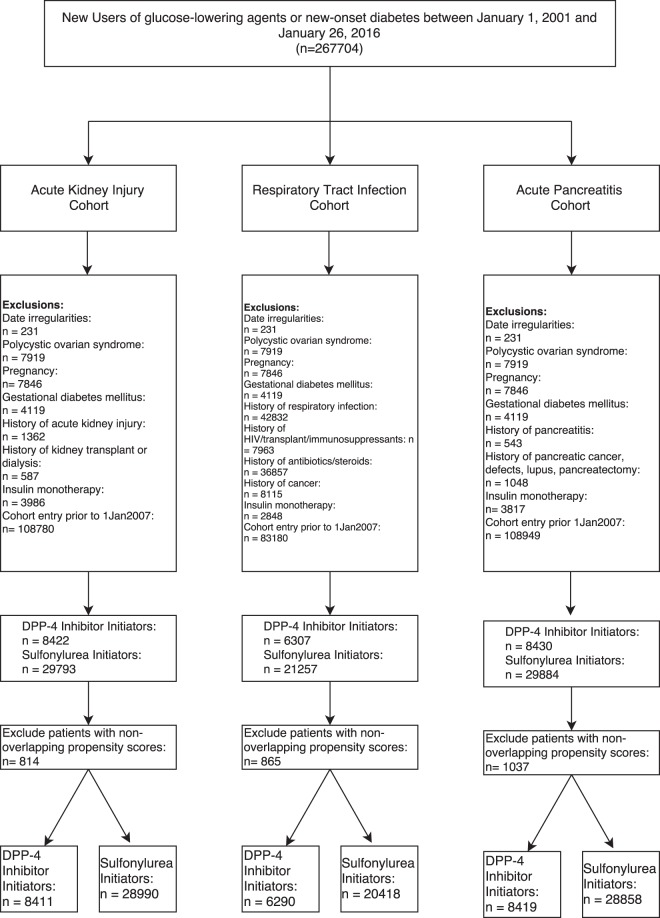

A total of 267,704 patients were included in our source population (Fig. 1). Of these, 139,285 were eligible for the acute kidney cohort, 103,159 were eligible for the acute respiratory tract cohort, and 139,518 were eligible for the acute pancreatitis cohort.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram to identify new-users of DPP4 inhibitors and sulfonylureas for each study cohort.

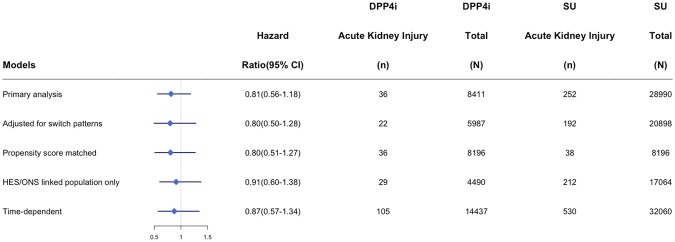

Within the acute kidney injury cohort, there were 8,411 DPP4 inhibitor and 28990 sulfonylurea initiators. Mean follow-up time was 307 days and ranged from 1 to 3300 days. On average, DPP4 inhibitor users had diabetes for a longer duration (2.0 years vs. 1.0 years), had few hospitalizations, were less likely to have a HbA1C above 9%, and were more likely to have been on metformin in the year prior to cohort entry (Table 1). However, after propensity score matching, baseline differences between groups were comparable (Supplementary Appendix Table S9). Within 31,470 years of person-time follow-up this cohort experienced 288 episodes of acute kidney injury among new users of DPP4 inhibitors (n = 36, incidence rate = 4.8 per 1000 person-years) and sulfonylureas (n = 252, incidence rate 10.5 per 1000 person-years) (Table 2). Unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) suggest a decreased risk of acute kidney injury among DPP4 inhibitors users compared to sulfonylurea users (HR = 0.46; 95% CI 0.32–0.65); however, following adjustment for potential confounding variables, the association attenuates to a neutral one (adjusted HR = 0.81; 95% CI 0.56–1.18). No significant associations were observed comparing DPP4 inhibitor initiators with thiazolidinedione initiators (adjusted HR = 1.12; 95% CI 0.60–2.10) or insulin users (adjusted HR = 1.40; 95% CI 0.77–2.55). Similarly, our sensitivity analysis showed no significant increased or decreased risk of acute kidney injury found among users of DPP4 inhibitors (Fig. 2). A significant association was found between DPP4 inhibitor initiation when compared to metformin initiation (adjusted HR = 1.85; 95% CI 1.10–3.12). When metformin was considered as a time-dependent variable, the association was no longer significant (adjusted HR = 1.39, 95% CI 0.91–2.11).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of new-users of DPP-4 inhibitors and sulfonylureas for each study cohort.

| Characteristics | New-user cohort for Acute Kidney Injury | p-value | New-user cohort for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections | p-value | New-user cohort for Acute Pancreatitis | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPP4i (n = 8,411) | SU (n = 28,990) | DPP4i (n = 6,290) | SU (n = 20,409) | DPP4i (n = 8.419) | SU (n = 28,858) | ||||

| Age in yrs (sd) | 57.5 (12.2) | 60.1 (13.7) | <0.01 | 57.1 (12) | 59.1 (13.4) | <0.01 | 57.5 (12.2) | 60.1 (13.7) | <0.01 |

| Female | 41.5% | 41.3% | 0.7 | 38.4% | 37.7% | 0.3 | 41.6% | 41.3% | 0.65 |

| Measure of deprivation | |||||||||

| Least | 9.4% | 10.5% | 9.9% | 10.6% | 9.5% | 10.6% | |||

| Most | 11% | 11.3% | 10.9% | 10.9% | 11% | 11.3% | |||

| Unknown | 46.7% | 40.5% | <0.01 | 46.5% | 40.8% | <0.01 | 46.6% | 40.3% | <0.01 |

| Diabetes duration, yrs (sd) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.5) | <0.01 | 2 (1.8) | 1.1 (1.5) | <0.01 | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.5) | <0.01 |

| Number of drugs in year prior to cohort entry | |||||||||

| 0–4 | 8.9% | 11% | 10.8% | 13.9% | 8.9% | 10.9% | |||

| 5–10 | 45.3% | 41.7% | 51% | 48.7% | 45.2% | 41.6% | |||

| 11+ | 45.8% | 47.3% | <0.01 | 38.2% | 37.4% | <0.01 | 45.8% | 47.5% | <0.01 |

| HbA1c | |||||||||

| <6.5% | 4.0% | 6.3% | 3.8% | 5.7% | 4.0% | 6.4% | |||

| 6.5–7.5% | 18.3% | 15.4% | 18.1% | 14.7% | 18.4% | 15.5% | |||

| 7.5–9% | 44.6% | 32.2% | 45% | 32.4% | 44.5% | 32.3% | |||

| 9%+ | 32.6% | 44.2% | 32.6% | 45.8% | 32.6% | 44% | |||

| Unknown | <1.0% | 1.9% | <0.01 | <1.0% | 1.3% | <0.01 | <1.0% | 1.8% | <0.01 |

| eGFR<60 | 14.2% | 19.5% | <0.01 | 12.9% | 17.4% | <0.01 | 14.3% | 19.9% | <0.01 |

| Diagnoses in year prior to cohort entry | |||||||||

| Heart Failure | 1.1% | 1.7% | <0.01 | <1.0% | 1.1% | 0.15 | 1.1% | 1.8% | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 18% | 20.1% | <0.01 | 17.1% | 19.2% | <0.01 | 17.9% | 20.4% | <0.01 |

| Cirrhosis | <1.0% | <1.0% | <0.01 | <1.0% | <1.0% | 0.17 | <1.0% | <1.0% | <0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3.7% | 5.0% | <0.01 | 3.4% | 4.7% | <0.01 | 3.6% | 5.1% | <0.01 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | <1.0% | <1.0% | <0.01 | <1.0% | <1.0% | 0.03 | <1.0% | <1.0% | <0.01 |

| Medications in year prior to cohort entry | |||||||||

| Metformin | 93.2% | 76% | <0.01 | 94.2% | 79.4% | <0.01 | 93.2% | 76.3% | <0.01 |

| Acarbose | <1.0% | <1.0% | S | <1.0% | <1.0% | S | <1.0% | <1.0% | S |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | <1.0% | <1.0% | <0.01 | <1.0% | <1.0% | 0.016 | <1.0% | <1.0% | 0.01 |

| Meglitinide | <1.0% | <1.0% | <0.01 | <1.0% | <1.0% | <0.01 | <1.0% | <1.0% | <0.01 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 4.3% | 1.9% | <0.01 | 4.4% | 2.1% | <0.01 | 4.3% | 1.9% | <0.01 |

| Insulin | 1.5% | 1.5% | 0.9 | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.6 | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1 |

S = suppressed due to low number of events.

Table 2.

Measures of frequency and association for acute outcomes of interest among new-users of DPP-4 Inhibitors (DPP4i) vs. sulfonylureas (SU), metformin, thiazolidinediones (TZD), or insulin.

| New-user cohort for Acute Kidney Injury | New-user cohort for Acute Respiratory Infections | New-user cohort for Acute Pancreatitis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPARATOR: SU | ||||||

| DPP4i | SU | DPP4i | SU | DPP4i | SU | |

| Number of patients | 8411 | 28990 | 6290 | 20409 | 8419 | 28858 |

| Person-years of follow-up, yrs | 7539 | 23931 | 5187 | 15587 | 7561 | 23959 |

| Number of Events | 36 | 252 | 537 | 1694 | 7 | 34 |

| Incidence per 1000 person-years (95%CI) | 4.8 (3.5–6.6) | 10.5 (9.3–11.9) | 103.5 (95.1–112.7) | 108.7 (103.6–114) | 0.9 (0.5–1.9) | 1.4 (1–2) |

| Crude HR (95%CI) | 0.46 (0.32–0.65) | -ref- | 0.94 (0.86–1.04) | -ref- | 0.63 (0.28–1.43) | -ref- |

| Adjusted HR (95%CI) | 0.81 (0.56–1.18) | -ref- | 0.93 (0.84–1.04) | -ref- | 1.03 (0.42–2.52) | -ref- |

| COMPARATOR: METFORMIN | ||||||

| DPP4i | Metformin | DPP4i | Metformin | DPP4i | Metformin | |

| Number of patients | 728 | 74249 | 470 | 53475 | 774 | 77817 |

| Person-years of follow-up, yrs | 546 | 64795 | 331 | 43006 | 7561 | 23959 |

| Number of Events | 16 | 365 | 36 | 4395 | S | 34 |

| Incidence per 1000 person-years (95%CI) | 29.3 (18.1–47.6) | 5.6 (5.1–6.2) | 108.7 (78.6–150.4) | 102.2 (99.3–105.3) | S | 1.4 (1–2) |

| Crude HR (95%CI) | 5.17 (3.13–8.54) | -ref- | 1.03 (0.74–1.43) | -ref- | S | -ref- |

| Adjusted HR (95%CI) | 1.85 (1.10–3.12) | -ref- | 0.91 (0.65–1.27) | -ref- | S | -ref- |

| COMPARATOR: TZD | ||||||

| DPP4i | TZD | DPP4i | TZD | DPP4i | TZD | |

| Number of patients | 13347 | 3347 | 9898 | 2563 | 13371 | 3347 |

| Person-years of follow-up | 12802 | 3617 | 8752 | 2517 | 12823 | 3630 |

| Number of Events | 63 | 17 | 891 | 245 | 12 | S |

| Incidence per 1000 person-years (95%CI) | 4.9 (3.9–6.3) | 4.7 (2.9–7.5) | 101.8 (95.3–108.7) | 97.3 (85.9–110.3) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | S |

| Crude HR (95%CI) | 1.02 (0.59–1.74) | -ref- | 1.01 (0.87–1.16) | -ref- | S | -ref- |

| Adjusted HR (95%CI) | 1.12 (0.60–2.10) | -ref- | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) | -ref- | 1.21 (0.25–5.72) | -ref- |

| COMPARATOR: INSULIN | ||||||

| DPP4i | Insulin | DPP4i | Insulin | DPP4i | Insulin | |

| Number of patients | 13881 | 4918 | 10205 | 3286 | 13991 | 4884 |

| Person-years of follow-up | 13433 | 1693 | 9177 | 1085 | 13511 | 1710 |

| Number of Events | 64 | 26 | 922 | 161 | 14 | 5 |

| Incidence per 1000 person-years (95%CI) | 4.8 (3.7–6.1) | 15.4 (10.5–22.5) | 100.5 (94.2–107.2) | 148.4 (127.2–173.2) | 1 (0.6–1.7) | 2.9 (1.3–6.8) |

| Crude HR (95%CI) | 0.39 (0.24–0.63) | -ref- | 0.72 (0.60–0.85) | -ref- | 0.42 (0.15–1.22) | -ref- |

| Adjusted HR (95%CI) | 1.40 (0.77–2.55) | -ref- | 0.74 (0.60–0.92) | -ref- | 1.01 (0.24–4.19) | -ref- |

S = suppressed due to low number of events.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analyses for the association between DPP4 Inhibitors (DPP4i) and Sulfonylurea (SU) users for acute kidney injury.

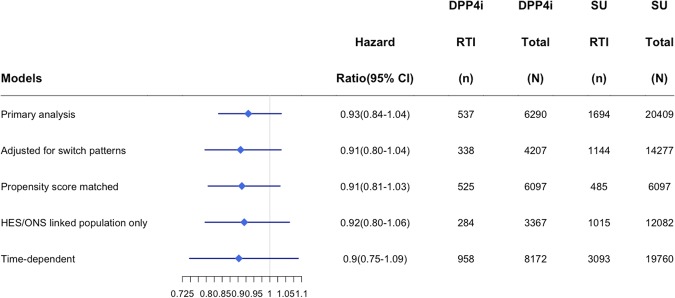

Within the acute respiratory tract infection cohort, there were 6,290 initiators of a DPP4 inhibitor and 20,409 initiators of a sulfonylurea (Fig. 1). Mean follow-up time was 284 days and ranged from 1 to 3023 days. Differences in populations prior to being matched by high-density propensity scores were similar to those in the acute kidney injury cohort (DPP4 users had longer duration of diabetes, fewer hospitalizations, fewer baseline HbA1C above 9%, and greater use of metformin in the past), and balanced out after matching (Table 2 and Supplementary Appendix Table S9). After 20,774 years of person-time follow-up this cohort experienced 2231 episodes of an incident acute respiratory tract infection among new users of DPP-4 inhibitors (n = 537, incidence rate 104 per 1000 person-years) and sulfonylureas (n = 1,694, incidence rate 109 per 1000 person-years) (Table 2). Both unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazard models suggest DPP4 inhibitors are not associated with a significant increase or decrease in respiratory tract infection risk (HR = 0.94; 95% CI 0.86–1.04; adjusted HR = 0.93; 95% CI 0.84–1.04). Comparisons of DPP4 inhibitors with metformin (adjusted HR = 0.91, 95% CI 0.65–1.27) or thiazolidinediones (adjusted HR = 1.02; 95% CI 0.86–1.21) also did not demonstrate an increased risk; however, comparisons with insulin showed DPP4 inhibitors were associated with a decreased risk of an acute respiratory tract infection (adjusted HR = 0.74; 95% CI 0.60–0.92). In sensitivity analysis findings remained consistent with the primary analysis showing no significant increased or decreased risk of respiratory tract infections among users of DPP-4 inhibitors (Fig. 3). In a sub-group analysis, DPP4 inhibitors were not associated with an increased risk of an upper respiratory tract infection (adjusted HR = 0.94; 95% CI 0.84–1.05); however, when examining pneumonia and influenza specifically, DPP4 inhibitors were found to have a protective effect over sulfonylureas (adjusted HR = 0.63; 95% CI 0.44–0.90).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analyses for the association between DPP4 Inhibitors (DPP4i) and Sulfonylurea (SU) users for respiratory tract infection (RTI).

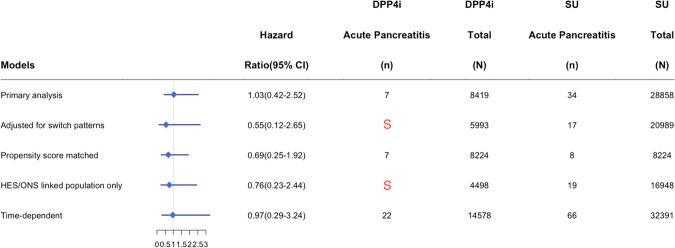

Within the acute pancreatitis cohort, there were 8,419 initiators of a DPP4 inhibitor and 28,858 initiators of a sulfonylureas (Fig. 1). Mean follow-up time was 308 days and ranged from 1 to 3300 days. Differences in baseline characteristics among groups prior to being matched by high-density propensity scores were similar to those in the acute kidney injury and respiratory tract infection cohorts and balanced out after matching (Table 2). After 31,520 years of person-time follow-up this cohort experienced 41 episodes of acute pancreatitis among new users of DPP4 inhibitors (n = 7, incidence rate = 0.9 per 1000 person-years) and sulfonylureas (n = 34, incidence rate 1.4 per 1000 person-years) (Table 2). Neither crude nor adjusted hazard ratios demonstrate a significant difference (HR = 0.63; 95% CI 0.28–1.43; adjusted HR = 1.03; 95% CI 0.42–2.52). Comparisons with thiazolidinediones (adjusted HR = 1.21; 95% CI 0.25–5.72) and insulin (adjusted HR = 1.01; 95% CI 0.24–4.19) did not demonstrate an increased risk. There were too few events to compare DPP4 inhibitor initiators to metformin initiators; however, when DPP4 inhibitor use was not associated with an increased or decreased risk of acute pancreatitis when compared to metformin in a time-varying model (adjusted HR = 1.51; 95% CI 0.48–4.75). Due to a small number of events, we were limited in the number of sensitivity analyses that we could conduct on this relationship (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analyses for the association between DPP4 Inhibitors (DPP4i) and Sulfonylurea (SU) users for acute pancreatitis. S = suppressed due to low number of events.

Discussion

Across a series of new-user cohorts consisting of patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK, we found that the incidence of acute kidney injury, respiratory tract infections, and acute pancreatitis were 4.8, 104, and 0.9 per 1,000 patient-years, respectively, among initiators of a DPP4 inhibitor. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, there was no statistically significant increased risk for either outcome when compared to new initiators of a sulfonylurea. These findings were robust and held in most secondary and sensitivity analyses.

Consistent with findings from randomized controlled trials and prior observational research10,44–46, our study suggests that DPP4 inhibitors do not increase the risk of acute kidney injury. Although our findings are comparable to observational studies evaluating the safety of saxagliptin12, two other observational studies have published inconsistent findings10,11. These discordant results may be potentially explained by chance or possible bias due to exposure definitions and time-related bias. For example, Shih et al., used the prescription termination date of DPP4 inhibitor to classify patients into current, recent, and past exposure categories; however, it is unclear if the current user category for which they observed the increased risk of an acute kidney injury was over-represented10. The risk of acute kidney injury was higher for current DPP4 inhibitor users, but not for recent or past users. The findings reported by Chao et al., appear to be susceptible to time-related bias as short-term DPP4 inhibitor users (<90 days duration) were excluded from the analysis, whereas no such exclusion criteria were applied to the control group11. Although we found an increased risk of acute kidney injury when comparing DPP4 inhibitor and metformin initiators, this comparison is highly susceptible to confounding by indication given metformin’s place in therapy and contraindication in patients with renal dysfunction. It is reasonable to suspect that there are unmeasured confounders at play that were considered during the prescribing process. Moreover, the substantial decrease in effect size between the crude (HR = 5.17) and adjusted (HR = 1.85) hazard ratios, as well as the lack of association within a time-dependent model suggest that a strong degree of confounding is present.

Prior observational studies examining the risk of DPP4 inhibitors and infections have examined all-cause infections12, upper respiratory tract infections13,or pneumonia18,19,48 as outcomes of interest. Similarly, the majority of meta-analysis pooling results from clinical trials suggest that there is not a significant risk of all-cause infection, upper respiratory tract infections, or pneumonia associated with using a DPP4 inhibitor. Our study expands on these findings using a contemporary follow-up period, multiple reference groups, and both upper and lower acute respiratory infections.

Several previous observational studies have examined the relationship between DPP4 inhibitors and acute pancreatitis. Our findings add to this evidence base suggesting that DPP4 inhibitors do not substantially increase the risk of acute pancreatitis compared to other glucose-lowering agents. However, given the small number of events, our study was limited in power to detect small or modest differences in the incidence of acute pancreatitis between exposure groups.

There are several limitations of this study to consider. As with any observational study, there is a possibility of residual and unmeasured confounding affecting study results. For example, the increased risk of acute kidney injury observed in our study for initiators of DPP4 inhibitors vs. metformin is susceptible to residual and unmeasured confounding given metformin’s contraindication in patients with renal impairment. We took steps to mitigate this risk, such as applying high-dimensional propensity scores to maximize the balance of measured baseline confounders. Second, our study cohorts all had limited follow-up time. Specifically, the mean follow-up times were 307, 284, and 308 days for the acute kidney injury, acute respiratory tract infection and acute pancreatitis cohorts, respectively. Therefore, our study is unable to quantify the long-term risks associated with DPP4 inhibitors. Third, our study, like others relying on secondary data sources, is susceptible to information bias via outcome measurement error. We used diagnostic codes that have been used previously, and which have variable positive predictive values (acute kidney injury ~17%; acute pancreatitis ~42%; respiratory tract infection ~97%)49–51. Finally, prescription data was used to measure exposure to diabetes therapies. It is possible that primary and secondary non-adherence may lead to an overestimation of exposure.

In conclusion, this study suggests that initiation of a DPP4 inhibitor was not associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury, respiratory tract infections, or acute pancreatitis compared to sulfonylureas or other glucose-lowering therapies. Further studies are required to quantify the potential for within-class differences among DPP4 inhibitors, and to explore modifying factors with respect to the association between DPP4 inhibitors and acute kidney injury, acute respiratory tract infections, and acute pancreatitis.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

JMG is supported as a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institute of Health Research and a Clinician Scientist Award from Diabetes Canada. JRD holds a CIHR Fellowship Award in Drug Safety and Effectiveness. This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN173599 – 287647). This study is based in part on data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink obtained under licence from the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. However, the interpretation and conclusions contained in this study are those of the author/s alone.

Author Contributions

J.M.G., E.C., W.K.M., L.K.T. and S.R.M., were involved in the concept and design of the study. J.M.G. and J.R.D. were responsible for drafting the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data. J.M.G., J.R.D., E.C., W.K.M., and L.K.T. provided revisions to the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-33483-y.

References

- 1.Hampp C, Borders-Hemphill V, Moeny DG, Wysowski DK. Use of Antidiabetic Drugs in the U.S., 2003–2012. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1367–1374. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipska KJ, et al. Trends in Drug Utilization, Glycemic Control, and Rates of Severe Hypoglycemia, 2006–2013. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:468–475. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemens KK, et al. Trends in Antihyperglycemic Medication Prescriptions and Hypoglycemia in Older Adults: 2002–2013. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0137596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J, et al. Incretin based treatments and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;357:j2499. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gamble J-M, et al. Incretin-based medications for type 2 diabetes: an overview of reviews. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2015;17:649–658. doi: 10.1111/dom.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haluzík Martin, Frolík Jan, Rychlík Ivan. Renal Effects of DPP-4 Inhibitors: A Focus on Microalbuminuria. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2013;2013:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/895102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marques C, et al. Sitagliptin Prevents Inflammation and Apoptotic Cell Death in the Kidney of Type 2 Diabetic Animals. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2014/538737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Websky K, Reichetzeder C, Hocher B. Physiology and pathophysiology of incretins in the kidney. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2014;23:54–60. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000437542.77175.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mega Cristina, Teixeira-de-Lemos Edite, Fernandes Rosa, Reis Flávio. Renoprotective Effects of the Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor Sitagliptin: A Review in Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2017;2017:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2017/5164292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih C-J, et al. Association Between Use of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors and the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury: A Nested Case-Control Study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016;91:867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao C-T, Wang J, Wu H-Y, Chien K-L, Hung K-Y. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor use is associated with a lower risk of incident acute kidney injury in patients with diabetes. Oncotarget. 2017;8:53028–53040. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo RV, et al. Postauthorization safety study of the DPP-4 inhibitor saxagliptin: a large-scale multinational family of cohort studies of five outcomes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2017;5:e000400. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willemen MJ, et al. Use of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors and the Reporting of Infections: A Disproportionality Analysis in the World Health Organization VigiBase. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:369–374. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell RK. Clarifying the Role of Incretin-Based Therapies in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Clin. Ther. 2011;33:511–527. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Food and Drug Administration Center for drug evaluation and research. Application number: 21–995. Medical review (2006).

- 16.Dal Pan, G. & Lindquist, M. K. Postmarketing spontaneous pharmacovigilance reporting systems. In Strom BL, Kimmel SE, Hennessy S, eds. In Pharmacoepidemiology (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012).

- 17.Karagiannis T, Paschos P, Paletas K, Matthews DR, Tsapas A. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the clinical setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e1369–e1369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorricho J, et al. Use of oral antidiabetic agents and risk of community-acquired pneumonia: a nested case–control study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017;83:2034–2044. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faillie J-L, Filion KB, Patenaude V, Ernst P, Azoulay L. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and the risk of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2015;17:379–385. doi: 10.1111/dom.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA investigating reports of possible increased risk of pancreatitis and pre-cancerous findings of the pancreas from incretin mimetic drugs for type 2 diabetes. (2013).

- 21.Elashoff M, Matveyenko AV, Gier B, Elashoff R, Butler PC. Pancreatitis, Pancreatic, and Thyroid Cancer With Glucagon-Like Peptide-1–Based Therapies. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:150–156. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European Medicines Agency. Byetta: European Public Assessment Report - Scientific Discussion. (2006).

- 23.Butler PC, Elashoff M, Elashoff R, Gale EA. A Critical Analysis of the Clinical Use of Incretin-Based Therapies: Are the GLP-1 therapies safe? Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2118–2125. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egan AG, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs - FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:794–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pyke C, et al. GLP-1 Receptor Localization in Monkey and Human Tissue: Novel Distribution Revealed With Extensively Validated Monoclonal Antibody. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1280–1290. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Assessment report for GLP-1 based therapies. (European Medicines Agency, 2013).

- 27.Nakamura, T. et al. PSCs and GLP-1R: occurrence in normal pancreas, acute/chronic pancreatitis and effect of their activation by a GLP-1R agonist. Lab. Invest. (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Dore DD, Seeger JD, Arnold Chan K. Use of a claims-based active drug safety surveillance system to assess the risk of acute pancreatitis with exenatide or sitagliptin compared to metformin or glyburide. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009;25:1019–1027. doi: 10.1185/03007990902820519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg R, Chen W, Pendergrass M. Acute Pancreatitis in Type 2 Diabetes Treated With Exenatide or Sitagliptin: A retrospective observational pharmacy claims analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2349–2354. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dore DD, et al. A cohort study of acute pancreatitis in relation to exenatide use. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011;13:559–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudhakaran C, Kishore U, Anjana RM, Unnikrishnan R, Mohan V. Effectiveness of Sitagliptin in Asian Indian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes—An Indian Tertiary Diabetes Care Center Experience. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2011;13:27–32. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romley JA, Goldman DP, Solomon M, McFadden D, Peters AL. Exenatide Therapy and the Risk of Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer in a Privately Insured Population. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2012;14:904–911. doi: 10.1089/dia.2012.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh S, et al. Glucagonlike Peptide 1–Based Therapies and Risk of Hospitalization for Acute Pancreatitis in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Population-Based Matched Case-Control Study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:534. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giorda CB, et al. Incretin therapies and risk of hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in an unselected population of European patients with type 2 diabetes: a case-control study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:g111–g115. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The French Pharmacovigilance Centers Network et al. Pancreatitis associated with the use of GLP-1 analogs and DPP-4 inhibitors: a case/non-case study from the French Pharmacovigilance Database. Acta Diabetol. 51, 491–497 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Faillie J-L, Azoulay L, Patenaude V, Hillaire-Buys D, Suissa S. Incretin based drugs and risk of acute pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes: cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g2780–g2780. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wenten M, et al. Relative risk of acute pancreatitis in initiators of exenatide twice daily compared with other anti-diabetic medication: a follow-up study: Acute pancreatitis risk. Diabet. Med. 2012;29:1412–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah BR, Hux JE. Quantifying the risk of infectious diseases for people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:510–513. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abu-Ashour W, et al. The association between diabetes mellitus and incident infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2017;5:e000336. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrett E, et al. Data Resource Profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015;44:827–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneeweiss S, et al. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology. 2009;20:512–522. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a663cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gamble J-M, et al. The risk of fragility fractures in new users of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors compared to sulfonylureas and other anti-diabetic drugs: A cohort study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018;136:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai L, Cai Y, Lu ZJ, Zhang Y, Liu P. The efficacy and safety of vildagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials: Meta-analysis for vildagliptin. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2012;37:386–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pendergrass M, Fenton C, Haffner SM, Chen W. Exenatide and sitagliptin are not associated with increased risk of acute renal failure: a retrospective claims analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012;14:596–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper ME, et al. Kidney Disease End Points in a Pooled Analysis of Individual Patient-Level Data From a Large Clinical Trials Program of the Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitor Linagliptin in Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2015;66:441–449. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eurich DT, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes: retrospective population based cohort study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2267–f2267. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zanden RWder, et al. Use of Dipeptidyl-Peptidase-4 Inhibitors and the Risk of Pneumonia: A Population-Based Cohort Study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0139367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Staa TP, Abenhaim L, Cooper C, Zhang B, Leufkens HG. The use of a large pharmacoepidemiological database to study exposure to oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures: validation of study population and results. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2000;9:359–366. doi: 10.1002/1099-1557(200009/10)9:5<359::AID-PDS507>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Staa T-P, Abenhaim L. The quality of information recorded on a UK database of primary care records: A study of hospitalizations due to hypoglycemia and other conditions. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 1994;3:15–21. doi: 10.1002/pds.2630030106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2010;60:e128. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.