Abstract

Background

With impending marijuana legislation in Canada, a broad understanding of the harms associated with marijuana use is needed to inform the clinical community and public, and to support evidence-informed public policy development. The purpose of the review was to synthesize the evidence on adverse health effects and harms of marijuana use.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Embase, PsycINFO, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and the Health Technology Assessment Database from the inception of each database to May 2018. Given that systematic reviews evaluating one or other specific harm have been published, this is an overview review with the primary objective of assessing a health effect or harm. Data on author, country and year of publication, search strategy and results, and outcomes were extracted. Quality was assessed using the AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) checklist.

Results

The final analysis included 68 reviews. Evidence of harm was reported in 62 reviews for several mental health disorders, brain changes, cognitive outcomes, pregnancy outcomes and testicular cancer. Inconclusive evidence was found for 20 outcomes (some mental health outcomes, other types of cancers and all-cause mortality). No evidence of harm was reported for 6 outcomes.

Interpretation

Harm was associated with most outcomes assessed. These results should be viewed with concern by physicians and policy-makers given the prevalence of use, the persistent reporting of a lack of recognition of marijuana as a possibly harmful substance and the emerging context of legalization for recreational use.

“Marijuana” refers to the dried leaves of the Cannabis sativa plant.1 Internationally, it is the most widely used illicit substance.2 About 2.5% of the world’s population uses marijuana, and it accounts for half of all drug seizures worldwide.2,3 In Canada, the rate of past-month marijuana use is about 10.5%.2 Users report feelings of excitement, euphoria, sensory distortion, sedation or drowsiness from using marijuana,4 which impel usage for similar reasons as alcohol, tobacco and other illicit substances. However, there are negative health effects associated with marijuana use.

Currently, marijuana is legal in 8 US states, Washington and Uruguay, with several other jurisdictions nationally and internationally actively developing legislation. Canada has legalization currently under consideration at the House of Commons, with legalization having already being considered once by the Senate; legalization is likely to occur by fall 2018. A broad understanding of the harms associated with marijuana use is needed to inform the clinical community and public, and to support evidence-informed public policy development. The individual health risks associated with marijuana use are widely reported in several focused systematic reviews.5–7 Syntheses have reported adverse events associated with medical use, the risks associated with use during pregnancy and the association of recreational use with impaired driving.8–11 A recent synthesis from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine included a variety of health effects associated with marijuana, but owing to the heterogeneity of the literature, and time constraints, the report’s breadth was limited to priorities.12 To date, there has been no complete picture of harms and risks published in the peer-reviewed literature.

The objective of this work was to synthesize comprehensively the evidence of the health effects and harms (e.g., mortality, mental health outcomes, respiratory illnesses and cardiovascular diseases) of nonmedical marijuana use within a general population, providing clinicians with a broad and comprehensive overview of possible health impacts. Owing to the broad nature of this review, we build on the robust existing synthesis literature; thus, we included systematic reviews. Any systematic review that reported on nonmedical use of cannabis within a population, included any study designs, and assessed any health effect or harm except a therapeutic outcome was included. This review is intentionally broad on the outcomes included to ensure that we captured the breadth of knowledge available.

Methods

Data sources

We conducted an overview review. Given that systematic reviews evaluating one or other specific harm have been published, this is an overview review with the primary objective of assessing a health effect or harm. Six databases were searched from inception until May 2018: MEDLINE (1947–May 3, 2018), The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005–May 3, 2018), Embase (1970–May 3, 2018), PsycINFO (1967–May 3, 2018), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (1937–May 3, 2018), and the Health Technology Assessment Database (1996–May 3, 2018). The search strategy was developed by 2 research associates (K.A.M. and L.E.D.) with expertise in search strategy design, and reviewed by a library and information specialist. Key terms focused on marijuana and negative health outcomes. Terms for marijuana, such as “cannabis,” “marihuana,” “pot” or “weed” were combined with terms for adverse health effects, such as “adverse event,” “harm,” “reaction,” “change” and “impairment,” and specific outcomes such as “cancer,” “depression” and “mortality.” The search was limited to English or French, systematic reviews or other reviews, and meta-analyses. No search of the grey literature was completed. The MEDLINE search is included in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/6/3/E339/suppl/DC1); the full search strategy for all databases is available from the authors on request.

Study selection

All abstracts were screened by 2 independent reviewers (K.A.M. and L.E.D.). Inclusion criteria were systematic review design, publication in English or French, focus on human or animal populations, report on nonmedical marijuana usage, and report an adverse health effect or harm. Abstracts were excluded if they failed to meet any of the inclusion criteria above. To ensure all relevant literature was captured, abstracts included by either reviewer proceeded to full-text review. All full texts were reviewed in duplicate by 2 independent reviewers (K.A.M. and L.E.D.). Any discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus. All identified full texts were hand searched for other articles that met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extracted from all studies included author, year and country of publication, search strategy, number of papers included, patient characteristics and key outcomes (data extraction and quality assessment were performed by K.A.M. and L.E.D.). When available, odds ratios, risk ratios and percentages were extracted. Quality was assessed using the AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) checklist. Items covered by AMSTAR include presence of an a priori design, duplicate selection and data extraction, listing of included and excluded studies, whether the status of publication was used as inclusion criteria, quality of included studies, likelihood of publication bias and appropriate mode of combining the studies.13 All studies were given a final quality score out of 11, with a score of 0–4 indicating low quality and a score of 9–11 indicating high quality.

Data synthesis and analysis

Studies were categorized by clinical area, and outcomes extracted included structural, functional or chemical brain changes, cognitive changes, cancer, changes in mental health, effects of prenatal exposure, death and other health effects.

Ethics approval

All data were from published studies so ethics approval was not required.

Results

Description of included reviews

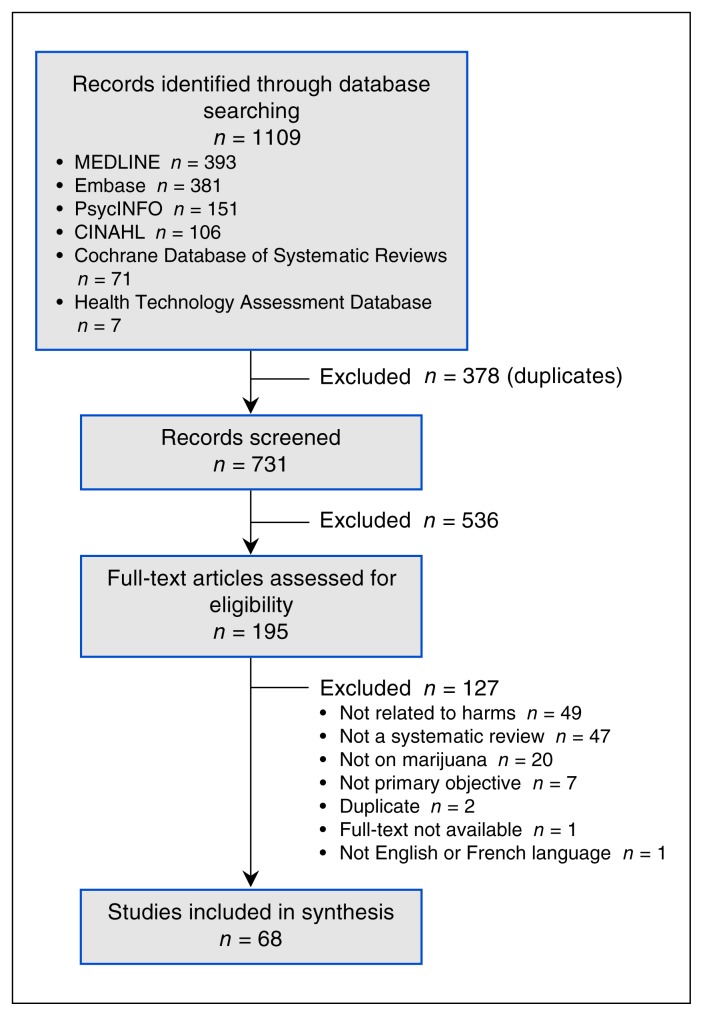

We identified 731 unique abstracts, of which 195 proceeded to full-text review. Sixty-eight systematic reviews were included in the final data set. The most common reason for exclusion was a lack of reporting of a health effect or harm (Figure 1). All were published between 1997 and 2017, and the most recent review was conducted in 2015. The most commonly searched databases were MEDLINE (53 reviews), Embase (39 reviews), PsycINFO (33 reviews) and PubMed (30 reviews) (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/6/3/E339/suppl/DC1). Twenty-two reviews examined mental health outcomes, 15 reported on functional and structural brain changes, 10 examined neurocognitive effects, 4 reported on cancer, 5 reported on prenatal exposure and 12 examined overall health effects (Table 1, Box 1).

Figure 1:

Flow diagram of inclusions and exclusions. CINAHL = Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

Table 1:

Summary of findings from 68 systematic reviews on adverse health effects and harms of marijuana use

| Area | Outcomes assessed | Reviews included | Primary studies included | Reviews that included randomized studies | Mean quality score* (range) | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain changes |

|

15 | 359 | 3 | 4.9 (1–8) | Association

|

| Cancer |

|

4 | 62 | None | 7.5 (5–9) | Association

|

| Mental health |

|

22 | 394 | None | 6.4 (1–10) | Association

|

| Neurocognitive effects |

|

10 | 462 | 1 | 4.9 (3–9) | Association

|

| Prenatal exposure |

|

5 | 69 | None | 5.4 (2–9) | Mother

|

| Overall health effects and harms |

|

12 | 213 | None | 3.8 (2–8) | Association

|

Note: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, GABA = γ-aminobutyric acid, NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

Quality score out of 11 (0–4 indicates low quality and 9–11 indicates high quality).

Box 1: An overview of the health effects and harms associated with marijuana use.

-

No evidence of harm

Overall health effects: arteritis

Cancer: lung, head and neck cancers

-

Inconclusive

Overall health effects: all-cause mortality, atrial fibrilation and bone loss

Mental health: psychosis in high-risk individuals, worsening psychotic symptoms, suicide, depression and anxiety

Cancer: bladder, prostate, penile, cervical and childhood cancers

Brain changes: white matter and blood flow changes

-

Evidence of harm

Overall health effects: driving, stroke, pulmonary function, cross-interaction with drugs and vision

Mental health: psychosis, mania, neurologic soft signs, relapse in patients with psychosis or schizophrenia, and dependence on cannabis

Cancer: testicular cancer

Social effects: impaired driving

Brain changes: decreased glutamate, changes in dopamine, decreased hippocampal volume and poorer global functioning

Neurocognitive changes: reduced memory, anhedonia and decreased efficiency

Harms associated with use during pregnancy: low birth weight, birth complications and long-term effects

Quality of included reviews

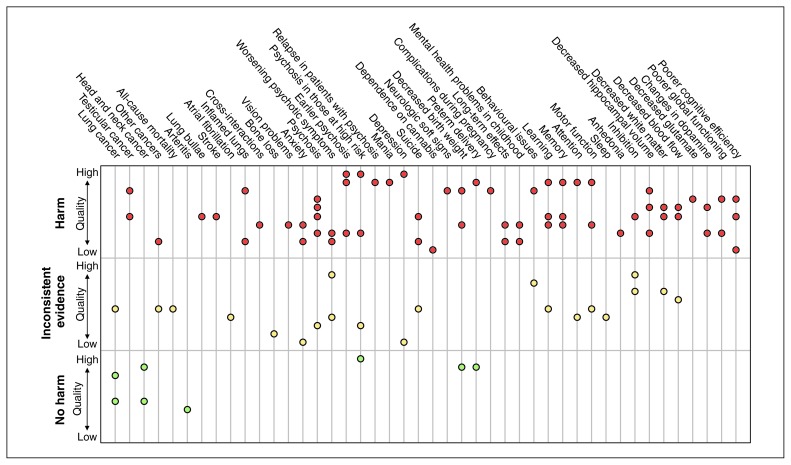

Twenty-eight reviews were of low quality, 29 were of moderate quality and 11 were of high quality. The lowest overall quality was in overall health effects and the highest was in cancer. Brain changes, prenatal exposure and overall health effects had no high-quality reviews (score of 9–11/11). There were 2 reviews with a quality score of 1/11,14,15 one in brain changes and another in mental health effects. Many reviews reported multiple outcomes, and, as such, some reviews concluded both harm and no harm for different outcomes. Overall, 62 of the assessed outcomes were associated with harm, for 20 outcomes there was insufficient evidence and for 6 outcomes there was no evidence of harm (Figure 2). In reviews that concluded harm, 20 were low quality6,14–32 and 9 were high quality.7,33–40 In those that concluded no evidence of harm, 5 were low quality21,23,31,41,42 and 4 were high quality.5,34,37,43 In those that reported inconsistent evidence, 5 were low quality20,44–47 and 1 was high quality.40 Five reviews identified randomized trials.20,48–51

Figure 2:

Summary of evidence. Each dot represents a systematic review. Each third represents the conclusion about harm: the bottom third is no evidence of harm, the middle third is inconsistent evidence and the top third is evidence of harm. Reviews are organized within each third based on quality such that higher quality are near the top of the respective third and lower quality reviews are near the bottom. Some reviews reported on multiple outcomes and are represented accordingly.

Effect of interventions

Brain changes

Of the 15 included reviews, 5 assessed structural changes, 3 examined functional changes, 4 assessed both structural and functional changes and 3 examined chemical changes. All papers reported either harm or insufficient evidence. Most (n = 13) examined neuroimaging primary studies, including structural, functional and volumetric magnetic resonance imaging; 18,44,48,49,52–54 diffusion tensor imaging;41,48,52,54,55 positron emission tomography;49 single photon emission tomography;49 magnetic resonance spectroscopy;14 pneumoencephalography; 18 and computed tomography.18

In otherwise healthy users, changes were observed in amygdala,44,48,52 hippocampal,44,48,52 and white and grey matter volume44,48,56 and blood flow,48,49,54,56 but there were no changes to whole brain volume,41,52 intracranial volume52 or the corpus callosum.41 Changes in learning,49 attention,48,54 memory48,49,54 and overall activity18 were observed. Many of the structural changes can help explain the functional changes. In users with schizophrenia or psychosis, white matter deficits55 and decreased global activity57 were observed. Disruptions in glutamate,53 dopamine,50 N-acetylaspartate,14 myo-inositol,14 choline,14 and γ-aminobutyric acid14 were observed in cannabis users.

Mental health

Twenty-one reviews examined marijuana and mental health. Reviews assessed the association between marijuana use and psychosis or schizophrenia (n = 15), anxiety (n = 2), suicide or depression (n = 2), mania (n = 1), neurologic soft signs (n = 1) and marijuana dependence (n = 1). Quality was variable, with 8 high-quality, 7 medium-quality and 7 low-quality reviews, with quality scores ranging from 1/11 to 10/11. None of the reviews included randomized trials. Most reviews compared marijuana users to nonusers, the general population or those at high risk of psychosis. Some reviews33,40 compared users to nonusers among people with schizophrenia. One review compared users with first-episode psychosis with users with long-term chronic psychosis.58

Psychosis and schizophrenia

There was an increased risk of schizophrenia and psychotic symptoms related to heavy (odds ratio [OR] 3.90, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.84–5.34), average (OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.68–2.31),59 ever (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.20–1.65),60 more frequent (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.54–2.84)60 and early use (OR 2.90, 95% CI 2.40–3.60)61 compared with never use. Compared with no use, cannabis use was associated with an earlier onset of psychosis38,43,47 (6.3, standardized mean difference [SMD] 1.56, 95% CI 1.40–1.72, yr).58 Cannabis use or abuse was also associated with transition to psychosis in those at “ultra-high risk” for psychosis (OR 1.75, 95% CI 1.135–2.710)37 relative to never users. Lastly, cannabis use in those with psychosis was related to increased relapse, readmission to hospital and decreased treatment adherence.33,40 Cannabis use was higher in those with first-episode psychosis.47 Any cannabis use was not associated with onset of psychosis in those at high risk or symptom severity compared with no use.37 There was no association with neurologic soft signs, or the neurologic abnormalities in sensory and motor performance that have been associated with schizophrenia during neurodevelopment.62

Mood, anxiety and suicide

Cannabis use, compared with no use, was associated with death by suicide (chronic users: OR 2.56, 95% CI 1.25–5.27),63 suicidal ideation (any use: OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.13–1.83; heavy use: OR 2.53, 95% CI 1.00–6.39),63 suicide attempt (any use: OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.24–4.00; heavy use: OR 3.20, 95% CI 1.72–5.94)63 and depression (any use: OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.05–1.30; heavy use: OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.21–2.16).39 Increased severity and duration of manic phases (OR 2.97, 95% CI 1.80–4.90)7 and higher levels of anxiety were observed.21 Those with anxiety were more likely to use cannabis (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.06–1.45)36 and develop cannabis use disorder (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.23–2.31).36

Dependency

About 10% of users experienced marijuana dependency; dependency increased with frequency of use.15 This review, however, was limited to self-reported surveys rather than formal diagnoses of dependency.15

Cognitive effects

Ten reviews assessed cognitive effects: 5 examined learning and memory, 5 examined executive function, 5 examined motor functioning, 3 examined reaction time, 4 examined attention, 2 examined forgetting/retrieval, 1 examined anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure) and 1 examined sleep. There was evidence of changes to functional and structural integrity,34 memory and learning,20,34 and increased anhedonia.22 There was inconsistent evidence regarding learning,23,64 attention,20,23,34,64 forgetting/retrieval,23,64 executive function, 20,23,34,64,65 motor and perceptual motor function,20,23,34,64,65 and sleep.46 There was no evidence of changes in reaction time,23,64,66 verbal/language skills23,64 or visual spatial function.34 In people with psychosis, cannabis use was not associated with a significant additional decline in general cognitive ability or intelligence,26 attention,26 executive abilities,26 working and learning memory,26,28 retrieval and cognition,26 language26 or visuospatial performance.26,28

Prenatal exposure

Five reviews examined marijuana use during pregnancy. Harms were reported for both the mother and the child. Pregnant women who used cannabis were more likely to experience anemia during pregnancy (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.10–1.69).35 Both reductions and increases in birth weight were reported (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.04–3.01, OR adjusted for tobacco use, other drug use, and socioeconomic and demographic factors 1.16, 95% CI 0.98–1.37).35,67 Compared with no use, there was a 48 g reduction in birth weight for those with any use (95% CI 14–83 g),6 131 g reduction for those who used at least 4 times per week (95% CI 52–209 g),6 and a 62 g increase for babies whose mothers used less than once a week (95% CI 8 g reduction to 132 g increase).6 However, women who smoked marijuana only were not at increased risk for preterm delivery compared with those who smoked both tobacco and marijuana (7.1% v. 5.7%; relative risk 1.25, 95% CI 0.63–2.50). Infants of users were more likely to be placed in the neonatal intensive care unit than those of nonusers (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.27–3.21).35

Children prenatally exposed to cannabis were more likely to experience inattention and impulsivity at 10 years. They also had lower IQ scores, increased errors of omission, academic underachievement (especially in spelling and reading), and increased rate of adolescent cannabis and cigarette use.31,32 There was no known association with congenital anomalies.31

Overall health effects and harms

Twelve reviews examined overall health effects assessing several different outcomes. Five examined cardiovascular outcomes. There was an association with stroke,68 atrial fibrillation, 69 bronchodilation,70 respiratory complications70,71 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.71 Some cases of increased lung bullae were identified.71 There was no association with arteritis.42 Cannabis interacts with tricyclic antidepressants, protease inhibitors and warfarin therapy, and the most commonly reported adverse effects of these interactions related to cardiac functioning.25 There were some residual effects on vision.29 Cannabis use was associated with an increased risk of fatal motor vehicle collisions11 (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.35–2.73).16

Five reviews examined cancer. Compared with never users, there was an increased risk of testicular cancer in current (OR 1.62 [95% CI 1.13–2.31]),72 weekly (OR 1.92 [95% CI 1.35–2.72]),72 and chronic users (OR 1.50 [95% CI 1.08–2.09]),72,73 but no increased risk of head and neck (OR 1.02 [95% CI 0.91–1.14])5 cancers. There was mixed evidence on lung cancer, with one review reporting a 2.1–4.1-fold increased risk in some marijuana users71 and another reporting no increased risk.74 One review noted increased pathologic lung changes in non–tobacco-smoking marijuana smokers compared with nonsmokers, but did not compare marijuana smokers and tobacco smokers.74 There was insufficient evidence regarding bladder, prostate, penile, cervical and childhood cancers to draw conclusions about the association between these outcomes and marijuana use.73

Interpretation

The 68 identified reviews reported harm for 62 outcomes, insufficient evidence of harm for 20 outcomes and no evidence of harm for 6 outcomes. Most reviews were of low to moderate quality; however, this is not a comment on the quality of the primary studies included within these reviews but an assessment of how well the systematic reviews reported methods and results. Harm is reported for multiple mental health outcomes, including psychosis, mania and suicide. There is evidence of structural, functional and chemical brain changes that may underlie some of the associated risk for mental illness. There is also evidence for impaired driving, and changes to memory, learning and hedonic value.

This review provides important information regarding the need to consider adverse health effects of recreational or medical marijuana use. This information should be of use to policymakers and health care systems as jurisdictions prepare to address the health effects of increased accessibility of marijuana. Data regarding harms associated with marijuana, including those related to mental health and brain changes should be considered when evaluating the potential impacts of legalizing marijuana, particularly related to the potential for increases in health care costs. As Canada prepares to legalize marijuana, there must be consideration of the impact on psychiatric and primary care practitioners, who are likely to encounter this within their practices. Although overall use is not expected to increase, as Canadians become more aware of the risks with marijuana, the health care system may observe an increase in patients presenting with the outcomes described.

Particular consideration should be given to special populations, namely pregnant women, adolescents, and those with risk for or established mental illness. Several reviews suggest that effects are worse in adolescent users compared with adult users.24,44,51,55,61 All reviews examining prenatal exposure and several reviews examining those with several mental illnesses suggested poorer outcomes for those who use marijuana compared with the general population. Public health campaigns or initiatives to inform these populations about the potential risks of use are required. Policy-makers may consider regulating marijuana from a public health perspective to reduce the harms among the most vulnerable groups. Physicians should also note this differential effect and advise youth, pregnant women and those with mental illnesses against use.

However, none of the above evidence is causal; only associative evidence is available. The study designs available within humans are limited to observational cohorts as sufficiently powered randomized controlled trials would not be feasible or ethical. It is possible that the observed positive associations are due to systematic differences between marijuana users and nonusers in underlying risks, social exposures or environmental factors. Nonetheless, clinicians should be aware that there is a variety of health harms associated with marijuana use and consider additional preventive measures for their patients, such as additional behavioural counselling and more assertive diagnostic approaches if symptoms arise.

Only 1 review examined dependency and was limited to examining only self-reported surveys; however, this review provides important information for physicians.15 This review reported that 10% of users meet criteria for marijuana dependency.15 There were moderate effects of genetics on dependency, and those who also smoked cigarettes, began smoking before the age of 17 and were weekly users were more likely to be dependent.15 Other reviews noted that those who were dependent on marijuana were more likely to develop psychosis, especially in those already at high risk,37 and users with anxiety were more likely to develop marijuana dependency.38 It is important for physicians to provide education to their patients that marijuana is not a harmless, recreational substance, particularly in groups at risk owing to personal or family history.

Our intention was to compile a comprehensive picture of the possible harms associated with marijuana use. With this goal, building on the existing literature, we completed an overview of reviews. Thus, we did not analyze at the level of individual studies. Our analysis is at the level of systematic review. It is possible that systematic reviews included the same individual primary studies. Indeed, it would be expected that systematics reviews would include overlapping literature. However, when multiple systematic reviews draw the same conclusions, this indicates the robustness of the conclusions and the replication of findings. In this work, multiple systematic reviews do report findings of harm in 20 of the outcomes assessed, most of which are mental health and poor pregnancy outcomes. Thus, with this evidence base, there should be particular attention paid to promoting responsible marijuana use, or abstinence, for those at high risk of mental illness and those who are pregnant.

Limitations

This review is limited in the range of potential harms that could be examined, as only topics previously systematically reviewed were included. Some adverse effects may therefore have been missed in this review. One such topic is the toxicity of marijuana compared with other licit and illicit substances. Compared with alcohol and tobacco, 2 legal and often-used substances, marijuana is less toxic at the population-level.75 Further, because of the nature of marijuana function on the brain, death due to overdose is not possible76 and marijuana has therefore been classified as a relatively safe drug, which it is in the short term. The safety profile of marijuana in the short term may have overshadowed some of the longer term health risks that appear to be associated with even moderate use. This review was limited to English and French reviews, which may have excluded some important reviews. Additionally, this review protocol was not registered in PROSPERO.

Conclusion

Though there is inconsistent evidence of variable quality, the general conclusion is that marijuana is associated with negative effects on several aspects of mental and physical health. With legalization impending in Canada, it is important to understand the likely impact of increased accessibility on health and health services, particularly in youth, pregnant woman and people living with mental illness. Better understanding of both the short- and long-term health effects of marijuana use is essential to inform public and clinical policy, as well as to adapt clinical services to anticipate changing clinical need.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: Eldon Spackman reports grants from Alberta Health Technology Decision Process. Tom Noseworthy reports a grant from the University of Calgary. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: K. Ally Memedovich, Laura Dowsett and Fiona Clement designed the study; K. Ally Memedovich and Laura Dowsett collected and managed the data; K. Ally Memedovich, Laura Dowsett and Fiona Clement analyzed the data; and all of the authors interpreted the data. K. Ally Memedovich, Laura Dowsett and Fiona Clement drafted the manuscript, which all of the authors reviewed. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/6/3/E339/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Leggett T United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. A review of the world cannabis situation. Bull Narc. 2006;58:1–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotermann M, Langlois K. Prevalence and correlates of marijuana use in Canada, 2012. Health Rep. 2015;26:10–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schauer GL, King BA, Bunnell RE, et al. Toking, vaping, and eating for health or fun: marijuana use patterns in adults, U.S., 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wachtel SR, ElSohly MA, Ross SA, et al. Comparison of the subjective effects of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and marijuana in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;161:331–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Carvalho MF, Dourado MR, Fernandes IB, et al. Head and neck cancer among marijuana users: a meta-analysis of matched case-control studies. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60:1750–5. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.English DR, Hulse GK, Milne E, et al. Maternal cannabis use and birth weight: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 1997;92:1553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbs M, Winsper C, Marwaha S, et al. Cannabis use and mania symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill KP. Medical marijuana for treatment of chronic pain and other medical and psychiatric problems: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313:2474–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volkow ND, Compton WM, Wargo EM. The risks of marijuana use during pregnancy. JAMA. 2017;317:129–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.18612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabria B, Degenhardt L, Hall W, et al. Does cannabis use increase the risk of death? Systematic review of epidemiological evidence on adverse effects of cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:318–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Wehmann RE, et al. Measuring early pregnancy loss: laboratory and field methods. Fertil Steril. 1985;44:366–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sneider JT, Mashhoon Y, Silveri MM. A review of magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies in marijuana using adolescents and adults. J Addict Res Ther. 2013;(Suppl 4) doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.S4-010. pii: 010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rey JM, Martin A, Krabman P. Is the party over? Cannabis and juvenile psychiatric disorder: the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1194–205. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000135623.12843.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asbridge M, Hayden JA, Cartwright JL. Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk: systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e536. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malchow B, Hasan A, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Cannabis abuse and brain morphology in schizophrenia: a review of the available evidence. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;263:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s00406-012-0346-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quickfall J, Crockford D. Brain neuroimaging in cannabis use: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:318–32. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben Amar M, Potvin S. Cannabis and psychosis: What is the link? J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:131–42. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broyd SJ, van Hell HH, Beale C, et al. Acute and chronic effects of cannabinoids on human cognition — a systematic review. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:557–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Martin-Santos R, et al. Cannabis and anxiety: a critical review of the evidence. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:515–23. doi: 10.1002/hup.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garfield JB, Lubman DI, Yücel M. Anhedonia in substance use disorders: a systematic review of its nature, course and clinical correlates. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48:36–51. doi: 10.1177/0004867413508455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant I, Gonzalez R, Carey CL, et al. Non-acute (residual) neurocognitive effects of cannabis use: a meta-analytic study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9:679–89. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703950016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Bec PY, Fatséas M, Denis C, et al. Cannabis and psychosis: search of a causal link through a critical and systematic review [article in French] Encephale. 2009;35:377–85. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindsey WT, Stewart D, Childress D. Drug interactions between common illicit drugs and prescription therapies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:334–43. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabin RA, Zakzanis KK, George TP. The effects of cannabis use on neurocognition in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2011;128:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reece AS. Chronic toxicology of cannabis. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47:517–24. doi: 10.1080/15563650903074507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoeler T, Kambeitz J, Behlke I, et al. The effects of cannabis on memory function in users with and without a psychotic disorder: findings from a combined meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2016;46:177–88. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwitzer T, Schwan R, Angioi-Duprez K, et al. The cannabinoid system and visual processing: a review on experimental findings and clinical presumptions. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:100–12. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szoke A, Galliot AM, Richard JR, et al. Association between cannabis use and schizotypal dimensions — a meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viteri OA, Soto EE, Bahado-Singh RO, et al. Fetal anomalies and long-term effects associated with substance abuse in pregnancy: a literature review. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32:405–16. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams JH, Ross L. Consequences of prenatal toxin exposure for mental health in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16:243–53. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoeler T, Monk A, Sami MB, et al. Continued versus discontinued cannabis use in patients with psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:215–25. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganzer F, Broning S, Kraft S, et al. Weighing the evidence: a systematic review on long-term neurocognitive effects of cannabis use in abstinent adolescents and adults. Neuropsychol Rev. 2016;26:186–222. doi: 10.1007/s11065-016-9316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunn JK, Rosales CB, Center KE, et al. Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009986. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kedzior KK, Laeber LT. A positive association between anxiety disorders and cannabis use or cannabis use disorders in the general population — a meta-analysis of 31 studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraan T, Velthorst E, Koenders L, et al. Cannabis use and transition to psychosis in individuals at ultra-high risk: review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2016;46:673–81. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Large M, Sharma S, Compton MT, et al. Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:555–61. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lev-Ran S, Roerecke M, Le Foll B, et al. The association between cannabis use and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2014;44:797–810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zammit S, Moore TH, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Effects of cannabis use on outcomes of psychotic disorders: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:357–63. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnone D, Abou-Saleh MT, Barrick TR. Diffusion tensor imaging of the corpus callosum in addiction. Neuropsychobiology. 2006;54:107–13. doi: 10.1159/000096992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grotenhermen F. Cannabis-associated arteritis. Vasa. 2010;39:43–53. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myles N, Newall H, Nielssen O, et al. The association between cannabis use and earlier age at onset of schizophrenia and other psychoses: meta-analysis of possible confounding factors. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:5055–69. doi: 10.2174/138161212802884816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorenzetti V, Lubman DI, Whittle S, et al. Structural MRI findings in long-term cannabis users: What do we know? Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:1787–808. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Meer FJ, Velthorst E, Meijer CJ, et al. Cannabis use in patients at clinical high risk of psychosis: impact on prodromal symptoms and transition to psychosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:5036–44. doi: 10.2174/138161212802884762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gates PJ, Albertella L, Copeland J. The effects of cannabinoid administration on sleep: a systematic review of human studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:477–87. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alharbi FF, El-Guebaly N. Cannabis and amphetamine-type stimulant-induced psychoses: a systematic overview. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2016;15:190–200. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Batalla A, Bhattacharyya S, Yücel M, et al. Structural and functional imaging studies in chronic cannabis users: a systematic review of adolescent and adult findings. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batalla A, Crippa JA, Busatto GF, et al. Neuroimaging studies of acute effects of THC and CBD in humans and animals: a systematic review. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:2168–85. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sami MB, Rabiner EA, Bhattacharyya S. Does cannabis affect dopaminergic signaling in the human brain? A systematic review of evidence to date. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:1201–24. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.James A, James C, Thwaites T. The brain effects of cannabis in healthy adolescents and in adolescents with schizophrenia: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2013;214:181–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rocchetti M, Crescini A, Borgwardt S, et al. Is cannabis neurotoxic for the healthy brain? A meta-analytical review of structural brain alterations in non-psychotic users. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:483–92. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colizzi M, McGuire P, Pertwee RG, et al. Effect of cannabis on glutamate signalling in the brain: a systematic review of human and animal evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;64:359–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martín-Santos R, Fagundo AB, Crippa JA, et al. Neuroimaging in cannabis use: a systematic review of the literature. Psychol Med. 2010;40:383–98. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cookey J, Bernier D, Tibbo PG. White matter changes in early phase schizophrenia and cannabis use: an update and systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies. Schizophr Res. 2014;156:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wrege J, Schmidt A, Walter A, et al. Effects of cannabis on impulsivity: a systematic review of neuroimaging findings. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:2126–37. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rapp C, Bugra H, Riecher-Rössler A, et al. Effects of cannabis use on human brain structure in psychosis: a systematic review combining in vivo structural neuroimaging and post mortem studies. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:5070–80. doi: 10.2174/138161212802884861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Myles H, Myles N, Large M. Cannabis use in first episode psychosis: meta-analysis of prevalence, and the time course of initiation and continued use. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:208–19. doi: 10.1177/0004867415599846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marconi A, Di Forti M, Lewis CM, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between the level of cannabis use and risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:1262–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19:187–94. doi: 10.1177/0269881105049040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruiz-Veguilla M, Callado LF, Ferrin M. Neurological soft signs in patients with psychosis and cannabis abuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paradox. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:5156–64. doi: 10.2174/138161212802884753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Borges G, Bagge CL, Orozco R. A literature review and meta-analyses of cannabis use and suicidality. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schreiner AM, Dunn ME. Residual effects of cannabis use on neurocognitive performance after prolonged abstinence: a meta-analysis. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20:420–9. doi: 10.1037/a0029117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gonzalez R, Carey C, Grant I. Nonacute (residual) neuropsychological effects of cannabis use: a qualitative analysis and systematic review. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42(Suppl 1):48S–57S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith JL, Mattick RP, Jamadar SD, et al. Deficits in behavioural inhibition in substance abuse and addiction: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:1–33. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Conner SN, Bedell V, Lipsey K, et al. Maternal marijuana use and adverse neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:713–23. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hackam DG. Cannabis and stroke: systematic appraisal of case reports. Stroke. 2015;46:852–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Korantzopoulos P, Liu T, Papaioannides D, et al. Atrial fibrillation and marijuana smoking. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:308–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tetrault JM, Crothers K, Moore BA, et al. Effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:221–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martinasek MP, McGrogan JB, Maysonet A. A systematic review of the respiratory effects of inhalational marijuana. Respir Care. 2016;61:1543–51. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gurney J, Shaw C, Stanley J, et al. Cannabis exposure and risk of testicular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:897. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1905-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang YH, Zhang ZF, Tashkin DP, et al. An epidemiologic review of marijuana and cancer: an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:15–31. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mehra R, Moore BA, Crothers K, et al. The association between marijuana smoking and lung cancer: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1359–67. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.13.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lachenmeier DW, Rehm J. Comparative risk assessment of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis and other illicit drugs using the margin of exposure approach. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8126. doi: 10.1038/srep08126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marijuana. Bethesda (MD): National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); [accessed 2018 May 1]. (updated June 2018). Available: www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.