Abstract

During ribosome biogenesis, ribosomal RNAs acquire various chemical modifications that ensure the fidelity of translation, and dysregulation of the modification processes can cause proteome changes as observed in cancer and inherited human disorders. Here, we report the complete chemical modifications of all RNAs of the human 80S ribosome as determined with quantitative mass spectrometry. We assigned 228 sites with 14 different post-transcriptional modifications, most of which are located in functional regions of the ribosome. All modifications detected are typical of eukaryotic ribosomal RNAs, and no human-specific modifications were observed, in contrast to a recently reported cryo-electron microscopy analysis. While human ribosomal RNAs appeared to have little polymorphism regarding the post-transcriptional modifications, we found that pseudouridylation at two specific sites in 28S ribosomal RNA are significantly reduced in ribosomes of patients with familial dyskeratosis congenita, a genetic disease caused by a point mutation in the pseudouridine synthase gene DKC1. The landscape of the entire epitranscriptomic ribosomal RNA modifications provides a firm basis for understanding ribosome function and dysfunction associated with human disease.

INTRODUCTION

Human ribosomes are comprised of two ribonucleoprotein subunits: the small subunit (40S) containing one ribosomal RNA (rRNA; 18S) and 33 ribosomal proteins, and the large subunit (60S) containing three rRNAs (5S, 5.8S, 28S) and 47 ribosomal proteins (1). In each subunit, rRNAs form the catalytic core for translation, and ribosomal proteins appear to stabilize and fine-tune ribosomal structure and function (2,3). Human ribosomes harbor numerous post-transcriptional modifications (PTMs), such as methylation or acetylation of the nucleotide base or the 2′-hydroxyl group of the ribose moiety, or conversion of uridine to pseudouridine (Ψ) (4–6). These PTMs are fundamental to global ribosome topology and functions (decoding, peptidyl transfer, translocation) and stabilize the structure either by influencing the local charge environment or increasing the hydrogen-bonding capability (7–10). In addition, the PTMs optimize the interaction of ribosomes with tRNAs, mRNAs and translation factors (9,11). Therefore, any alteration of rRNA PTMs can negatively impact both translation rate and accuracy (12–14) and impair responses to metabolites and antibiotics (15). Moreover, certain PTMs are associated with altered translation in various diseases, such as cancer and infectious diseases (16–18). Therefore, the complete identification of the PTMs and their sites in human ribosomes would constitute a major advance for understanding ribosome-associated cellular physiology and pathology.

Recently, using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), >130 individual rRNA modifications were visualized on the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the human 80S ribosome, and many of these PTMs were posited to be human-specific modifications (19). A large proportion of these PTMs, however, is inconsistent with those reported previously (4,5,20,21 and reference therein) in terms of both the types of chemical groups and sites of modification in human rRNA. Using a method for quantitative RNA analysis based on mass spectrometry (MS) technology termed SILNAS (stable isotope–labeled ribonucleic acid as an internal standard), we, for the first time, mapped all PTMs of the 80S ribosome from two eukaryotes, namely the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (22) and the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (23). Then, as a part of a cryo-EM analysis, we determined the PTMs in the Leishmania ribosome that are involved in binding the aminoglycoside paromomycin (24). We, therefore, took advantage of this technology to determine all PTMs in the entire rRNAs of the human 80S ribosome. We further investigated how human disease might alter the landscape of rRNA PTMs by assessing the PTMs of rRNAs of the 80S ribosome from patients with familial dyskeratosis congenita (DC) caused by mutations in the gene DKC1, the product of which converts uridine to Ψ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Standard laboratory chemicals were obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries. Sodium guanosine-13C10 5′-triphosphate (98 atom% 13C) and RNase A were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium cytidine-13C9 5′-triphosphate and sodium uridine-13C9 5′-triphosphate (98 atom% 13C) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. 5,6-D2-uridine was obtained from C/D/N Isotopes. RNase T1 was purchased from Worthington and further purified by reversed-phase LC before use. Triethylammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.0) was purchased from Glen Research. Chemically synthesized oligonucleotides were obtained from JBioS (the oligonucleotide sequences are given in Supplementary Table S1).

Cells and culture conditions

TK6 cell (human lymphoblast cell from spleen, Epstein-Barr virus transformed) and HeLa cell (human epithelial cell from cervix, adenocarcinoma) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. TK6 and HeLa cells were cultured at 37°C as described (25,26). Media used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S2. To obtain U/C-5,6-D2-labeled rRNAs, TK6 cells deficient in UMPS were cultured in the U/C-5,6-D2 labeling medium containing 330 μM 5,6-D2-uridine instead of uridine with natural isotope distribution.

DC fibroblasts, lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL), and control cells were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories (GM01774, GM01786, GM01787, AG04645, GM03194, GM03195, GM03650 and AG03738, https://www.coriell.org/) or the repositories of the National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition (KURB1983, http://cellbank.nibiohn.go.jp/). Cells were maintained in DMEM with 20% fetal bovine serum or RPMI 1640 with 2 mM l-glutamine and 15% fetal bovine serum. Information concerning the pathology associated with these cells is summarized in Supplementary Table S3.

Generation of UMPS deficient TK6 cells

To confirm the site of pseudouridylation, TK6 cells deficient in uridine monophosphate synthetase were generated to block de novo synthesis of uridine and grown in culture medium containing 5,6-D2-uridine (Supplementary Table S2) to differentiate the molecular mass of uridine from that of Ψ. The method used was CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology (27) targeting human UMPS gene (Gene ID: 7372, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/7372), and proper gene-targeting events with UMPS were confirmed by PCR using the genome DNA as a template. The details will be described elsewhere.

Preparation of cellular RNA

Total RNA (20 μg) was prepared from 10 ml TK6 cell culture (∼1.0 × 106 cell/ml) using Sepasol-RNA I Super G (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). rRNAs were purified from the total cellular RNA (∼15 μg) by reversed-phase LC on a PLRP-S 300Å column (2.1 × 100 mm, 3 μm, Agilent Technologies) or 4000 Å column (4.6 × 150 mm, 10 μm, Agilent Technologies) (28). A rRNA preparation of >95% purity was used for this study.

In vitro transcription of internal standard RNAs for SILNAS

To construct the plasmids for in vitro transcription of internal standard RNAs, DNAs encoding human 5S, 5.8S and 18S rRNAs were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA (PCR primers are noted in Supplementary Table S1). The amplified DNAs for 5S and 5.8S rRNAs were inserted into the EcoRI/XhoI sites of plasmid pBluescript II KS(+) (Agilent Technologies). For 18S rRNA, the amplified DNA was inserted into the KpnI/XhoI sites of plasmid pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For 28S rRNA, the 5′-terminal half of the PCR-amplified DNA (HindIII/BglII digest, ∼2.4 kb) and 3′-terminal half of the chemically synthesized DNA (BglII/XhoI digest, ∼2.7 kb, Wako Pure Chemical Industries) were ligated into pcDNA3.1(+) because we failed to amplify the 3′-terminal half of the DNA including the extremely GC-rich region. Before in vitro transcription, the plasmid was linearized with SpeI or XhoI to terminate the product at the end of the rRNA. To synthesize RNA, 2 μg of template DNA was incubated and transcribed using a Megascript T3 or T7 kit (Invitrogen). When RNA was synthesized, guanosine-13C10 5′-triphosphate, cytidine-13C9 5′-triphosphate, or uridine-13C9 5′-triphosphate solution was used instead of the respective 5′-triphosphate reagent that contained carbons with a natural isotope distribution. The RNA was precipitated in ethanol, solubilized in nuclease-free water, and purified further by reversed-phase LC as described above (Supplementary Figure S1).

Direct nanoflow LC-MS and tandem MS (MS/MS) analysis of RNA fragments

Nucleolytic RNA fragments were analyzed with a direct nanoflow LC-MS system as described (29). The LC eluate was sprayed online at –1.3 kV with the aid of a spray-assisting device (30) to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in negative ion mode. Other settings were as described (23,31).

Database search and interpretation of MS/MS RNA spectra

Ariadne (32) was used for database searches and assignment of MS/MS RNA spectra. We used the human genome database as a resource in conjunction with Ariadne (30). The following default search parameters for Ariadne were used: maximum number of missed cleavages, 1; variable modification parameters, two methylations per RNA fragment for any residue; RNA mass tolerance, ±5 ppm and MS/MS tolerance, ±20 ppm. For assignment of Ψ residues using 5,6-D2-uridine labeled RNAs, the mass table and the variable modification parameters were altered from default values to ‘5,6D_CU’ and ‘Ψ’, respectively, because both C and U were labeled with the medium and the pseudouridylation reaction results in the exchange of the position 5 deuterium of 5,6-D2-uridine to the proton of solvent, providing a −1 Da mass shift (33). The Ψ-characteristic signature ion at m/z 207.041 and 208.047 (for rRNAs containing natural and 6-D-labeled Ψ, respectively) was also used for assignment of Ψ (31).

SILNAS-based quantitation of the stoichiometry of PTM

SILNAS-based quantitation was performed as described (23). In brief, RNA (∼100 fmol) from natural sources or cells grown in guanosine with natural isotope distribution was mixed with an equal amount of synthetic RNA transcribed in vitro with 13C-labeled guanosine. The 1:1 RNA mixing was performed based on the measurement of the absorbance at 260 nm and ensured later by a correction factor obtained experimentally by the quantitative analysis of ∼10 labeled and non-labeled RNA fragment pairs with known nucleotide sequences without modifications. The mix was digested with RNase T1 (∼4 ng/μl) in 100 mM triethylammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.0) at 37°C for 60 min. RNase A digested RNA fragments were produced by the same procedure using a reference RNA transcribed in vitro with 13C-labelled cytidine and uridine. The stoichiometry of RNA modification at each site was estimated by Ariadne program designed for SILNAS. In principle, the program first extracts the intensity of MS signals from raw data, assigns all pairs of light and heavy signal of RNA fragments produced by SILNAS, compares quantitatively the signal intensities of each pair, and determines the stoichiometry of modification as the ratio of the difference in signal intensities between the light (unmodified) and heavy (a sum of unmodified and modified) fragments to the signal intensity of the heavy isotope-labeled fragment. Upon calculation, Ariadne program considers the isotopical impurities in commercial rNTPs (∼2%) and corrects the estimate by a correction factor obtained experimentally as described above. Finally, the results were confirmed by manual inspection of the original MS spectrum to examine whether the estimates are based on ‘uncontaminated’ MS signals.

The stoichiometries of modifications in TK6 rRNAs were estimated with the fragments having unique nucleotide sequence to remove redundant sequence derived from multiple rRNA positions. To obtain such fragments that contain modified nucleoside(s) within the unique nucleotide sequence, we designed and performed systematic RNase H cleavage of full-length rRNA in many cases. The stoichiometries of rRNA modifications in DC-related cells, however, were estimated solely by the analysis of RNase T1 fragments without removing the redundancy of fragments. Thus, the modifications in the fragments with redundant nucleotide sequence were estimated with lower stoichiometries than those in the fragments with less redundant or unique nucleotide sequence. To evaluate the estimated stoichiometries of modification at each site, the numbers of redundant sequence are provided in Supplementary Tables S4-1, S4-2 and S4-3.

Other procedures for RNA analysis

Sequence-specific RNase H cleavage of rRNAs was performed as described (22,23). All RNA/DNA sequences used for the cleavage are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The resulting RNase H fragments were separated by reversed-phase LC as described above for further digestion with other RNases. The masses of RNA fragments and a-, c-, w- and y-series ions were calculated with Ariadne (http://ariadne.riken.jp/). For the calculation of the C/U-5D-labeled fragment, 98 atom% deuterium was used. The tertiary structure of each rRNA, as defined by the PDB file, was analyzed with Swiss-Pdb viewer (http://spdbv.vital-it.ch/).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Human rRNAs harbor 14 distinct types of PTMs at 228 internal sites

To determine the PTMs of human rRNAs in TK6 cells, we applied SILNAS (22) to 5S, 5.8S, 18S, and 28S rRNAs that had been purified by reversed-phase liquid chromatography (LC) (28). Each purified rRNA was mixed with an in vitro transcribed G-13C10-labeled (guanosine labeled with 10 13C-atoms) reference RNA having the same sequence as each sample RNA; the mixture was digested with RNase T1 and analyzed with a nanoflow LC-coupled MS system equipped with Ariadne software to identify each RNA fragment and to detect modified oligonucleotides (for details, see Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). To align the RNase T1 fragments and identify all PTMs, we performed a similar analysis for RNase A digests of each rRNA with in vitro transcribed cytidine-13C9- and uridine-13C9-labeled reference RNAs; when the rRNA produced multiple fragments having the same nucleotide sequence, the undigested rRNA was systematically cleaved with RNase H (after annealing with a corresponding complementary DNA) to avoid the production of such fragments and to distinguish the redundant sequences prior to subsequent digestion with RNase T1 or A (Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). Thus, all RNA fragments were detected and quantitated in this study regardless of presence or absence of PTM. We also confirmed all pseudouridylation sites via analysis of rRNAs prepared from the UMPS-deficient TK6 cells that had been genetically modified using the CRISPR/Cas9 technique to block de novo synthesis of uridine and grown in culture medium containing 5,6-D2-uridine to differentiate the molecular mass of uridine from that of Ψ (Taoka et al., manuscript in preparation). Thus, we could unequivocally align all the nucleolytic fragments covering the entire rRNA sequences and construct a complete PTM map of human rRNAs.

The SILNAS technology allows comprehensive quantitative identification of all RNA PTMs exceeding ∼5% in stoichiometry (22). Under the criteria, the human 80S ribosome was found to harbor 14 distinct types of PTMs at 228 internal sites (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S5): 4 in 5.8S (total length, 157 nt), 91 in 18S (1869 nt) and 133 in 28S (5064 nt). No PTMs were found in 5S rRNA (120 nt). Because PTMs of human rRNAs affect the structure, function, and biogenesis of ribosomes and because dysregulation of PTMs has been implicated in cancer and inherited human disorders, the analysis of rRNA PTMs has been the subject of numerous studies over decades. In fact, of the 228 PTM sites identified in this study, 218 were consistent with the results of previous studies (Supplementary Table S6 and references therein); however, we detected unmodified U at position 688 in 18S rRNA and at position 4501 in 28S rRNA instead of Ψ described in the snoRNABase site (4) (https://www-snorna.biotoul.fr/). The latter terminates the argument about the site of pseudouridylation, 4501 (34) or 4502 (35), by proving the sequence U4501-Ψ4502. Likewise, we found unmodified C at position 2279 in 28S rRNA instead of Cm (2′-O-methyl cytosine) described by Incarnato et al. (5) (Supplementary Figure S4). Moreover, we detected 10 additional PTM sites, comprising 3 ribose 2′-O-methylations and 7 pseudouridylations (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S5), most of which are located in the functionally important interior region of the ribosome: Cm621, Ψ897, Ψ1045, Ψ1136, and Ψ1232 in 18S, and Um1760, Ψ1768, Ψ2619, Gm3606 and Ψ4463 in 28S. In particular, Cm621 in 18S is located at the decoding center. To provide the basis for these 2′-O-methylation/pseudouridylation reactions, we presented the candidate guide snoRNA responsible for modification at each site (Supplementary Figure S6), as predicted by Snoscan software (36) (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/snoscan/) or the in-house program (23) using the snoRNA sequences compiled in snoRNA Atlas database (37) (http://snoatlas.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/index.php).

Table 1.

Position, type, and stoichiometry of modified nucleotides found in human rRNAs

| rRNA | Modified nucleotide | Typea | Percent modification | rRNA | Modified nucleotide | Typea | Percent modification | rRNA | Modified nucleotide | Typea | Percent modification | rRNA | Modified nucleotide | Typea | Percent modification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.8S | 14 | Um | 5 | 18S | 1004 | Ψ | 97 | 28S | 1768 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 3866 | Cm | 99 |

| 5.8S | 55 | Ψ | 60 | 18S | 1031 | Am | 97 | 28S | 1769 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 3878 | Gm | 98 |

| 5.8S | 69 | Ψ | 61 | 18S | 1045 | Ψ | 92 | 28S | 1779 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 3899 | Ψ | 100 |

| 5.8S | 75 | Gm | 87 | 18S | 1046 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 1847 | Ψ | 95 | 28S | 3904 | Um | 96 |

| 18S | 1056 | Ψ | 93 | 28S | 1849 | Ψ | 95 | 28S | 3923 | Gm | 80 | ||||

| 18S | 27 | Am | 100 | 18S | 1081 | Ψ | 94 | 28S | 1858 | Am | 96 | 28S | 3938 | Ψ | 93 |

| 18S | 34 | Ψ | 100 | 18S | 1136 | Ψ | 7 | 28S | 1868 | Cm | 35 | 28S | 4020 | Gm | 83 |

| 18S | 36 | Ψ | 82 | 18S | 1174 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 2338 | Cm | 99 | 28S | 4032 | Cm | 100 |

| 18S | 93 | Ψ | 87 | 18S | 1177 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 2350 | Am | 100 | 28S | 4166 | Gm | 98 |

| 18S | 99 | Am | 99 | 18S | 1232 | Ψ | 98 | 28S | 2351 | Gm | 100 | 28S | 4190 | m6A | 100 |

| 18S | 105 | Ψ | 99 | 18S | 1238 | Ψ | 97 | 28S | 2352 | Cm | 90 | 28S | 4197 | Um | 97 |

| 18S | 109 | Ψ | 99 | 18S | 1244 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 2388 | Am | 73 | 28S | 4198 | Gm | 92 |

| 18S | 116 | Um | 98 | 18S | 1248 | m1acp3Ψ | 100 | 28S | 2402 | Um | 87 | 28S | 4263 | Ψ | 98 |

| 18S | 119 | Ψ | 94 | 18S | 1272 | Cm | 47 | 28S | 2409 | Cm | 98 | 28S | 4266 | Ψ | 90 |

| 18S | 121 | Um | 98 | 18S | 1288 | Um | 98 | 28S | 2411 | Gm | 90 | 28S | 4269 | Ψ | 93 |

| 18S | 159 | Am | 96 | 18S | 1326 | Um | 100 | 28S | 2495 | Ψ | 92 | 28S | 4276 | Um | 88 |

| 18S | 166 | Am | 100 | 18S | 1328 | Gm | 100 | 28S | 2619 | Ψ | 90 | 28S | 4282 | Ψ | 83 |

| 18S | 172 | Um | 96 | 18S | 1337 | ac4C | 79 | 28S | 2774 | Am | 84 | 28S | 4323 | Ψ | 95 |

| 18S | 174 | Cm | 92 | 18S | 1347 | Ψ | 98 | 28S | 2791 | Cm | 93 | 28S | 4331 | Ψ | 93 |

| 18S | 210 | Ψ | 83 | 18S | 1367 | Ψ | 98 | 28S | 2802 | Am | 92 | 28S | 4340 | Gm | 99 |

| 18S | 218 | Ψ | 100 | 18S | 1383 | Am | 98 | 28S | 2811 | Cm | 87 | 28S | 4362 | Gm | 97 |

| 18S | 296 | Ψ | 25 | 18S | 1391 | Cm | 95 | 28S | 2824 | Um | 99 | 28S | 4373 | Ψ | 96 |

| 18S | 354 | Um | 20 | 18S | 1442 | Um | 78 | 28S | 2826 | Ψ | 20 | 28S | 4390 | Ψ | 99 |

| 18S | 406 | Ψ | 87 | 18S | 1445 | Ψ | 90 | 28S | 2830 | Ψ | 9 | 28S | 4393 | Ψ | 97 |

| 18S | 428 | Um | 76 | 18S | 1447 | Gm | 34 | 28S | 2848 | Cm | 72 | 28S | 4401 | Ψ | 89 |

| 18S | 436 | Gm | 76 | 18S | 1490 | Gm | 100 | 28S | 2863 | Gm | 49 | 28S | 4412 | Ψ | 100 |

| 18S | 462 | Cm | 100 | 18S | 1625 | Ψ | 79 | 28S | 3606 | Gm | 96 | 28S | 4417 | m5C | 100 |

| 18S | 468 | Am | 99 | 18S | 1639 | m7G | 100 | 28S | 3616 | Ψ | 89 | 28S | 4426 | Cm | 98 |

| 18S | 484 | Am | 97 | 18S | 1643 | Ψ | 96 | 28S | 3618 | Ψ | 95 | 28S | 4427 | Ψ | 98 |

| 18S | 509 | Gm | 98 | 18S | 1668 | Um | 8 | 28S | 3674 | Ψ | 99 | 28S | 4441 | Ψ | 87 |

| 18S | 512 | Am | 83 | 18S | 1678 | Am | 94 | 28S | 3680 | Cm | 100 | 28S | 4463 | Ψ | 17 |

| 18S | 517 | Cm | 100 | 18S | 1692 | Ψ | 98 | 28S | 3694 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 4464 | Gm | 91 |

| 18S | 572 | Ψ | 97 | 18S | 1703 | Cm | 92 | 28S | 3697 | Am | 88 | 28S | 4468 | Um | 100 |

| 18S | 576 | Am | 96 | 18S | 1804 | Um | 86 | 28S | 3703 | Am | 100 | 28S | 4469 | Gm | 100 |

| 18S | 590 | Am | 72 | 18S | 1832 | m6A | 99 | 28S | 3709 | Ψ | 72 | 28S | 4470 | Ψ | 100 |

| 18S | 601 | Gm | 89 | 18S | 1842 | ac4C | 99 | 28S | 3713 | Ψ | 98 | 28S | 4491 | Ψ | 91 |

| 18S | 609 | Ψ | 90 | 18S | 1850 | m62A | 94 | 28S | 3723 | Gm | 83 | 28S | 4493 | Am | 87 |

| 18S | 621 | Cm | 62 | 18S | 1851 | m62A | 94 | 28S | 3737 | Ψ | 85 | 28S | 4500 | m3U | 120 |

| 18S | 627 | Um | 99 | 28S | 3739 | Am | 90 | 28S | 4502 | Ψ | 100 | ||||

| 18S | 644 | Gm | 98 | 28S | 389 | Am | 98 | 28S | 3741 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 4506 | Cm | 100 |

| 18S | 649 | Ψ | 93 | 28S | 391 | Am | 98 | 28S | 3743 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 4522 | Ψ | 98 |

| 18S | 651 | Ψ | 93 | 28S | 1303 | Gm | 71 | 28S | 3747 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 4541 | Am | 43 |

| 18S | 668 | Am | 99 | 28S | 1309 | m1A | 100 | 28S | 3749 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 4546 | Ψ | 100 |

| 18S | 681 | Ψ | 67 | 28S | 1310 | Am | 44 | 28S | 3761 | m5C | 100 | 28S | 4549 | Ψ | 100 |

| 18S | 683 | Gm | 99 | 28S | 1313 | Am | 100 | 28S | 3764 | Am | 96 | 28S | 4560 | Am | 37 |

| 18S | 686 | Ψ | 95 | 28S | 1327 | Cm | 92 | 28S | 3771 | Gm | 100 | 28S | 4588 | Gm | 75 |

| 18S | 797 | Cm | 68 | 28S | 1509 | Gm | 99 | 28S | 3787 | Cm | 80 | 28S | 4590 | Um | 82 |

| 18S | 799 | Um | 98 | 28S | 1511 | Am | 99 | 28S | 3797 | Ψm | 100 | 28S | 4593 | Gm | 100 |

| 18S | 801 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 1521 | Am | 109 | 28S | 3801 | Ψ | 50 | 28S | 4598 | Ψ | 92 |

| 18S | 814 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 1523 | Ψ | 88 | 28S | 3804 | Am | 92 | 28S | 4606 | Ψ | 42 |

| 18S | 815 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 1569 | Ψ | 68 | 28S | 3809 | Am | 100 | 28S | 4607 | Gm | 100 |

| 18S | 822 | Ψ | 99 | 28S | 1612 | Gm | 100 | 28S | 3820 | Cm | 100 | 28S | 4643 | Ψ | 39 |

| 18S | 863 | Ψ | 95 | 28S | 1664 | Ψ | 97 | 28S | 3823 | Ψ | 66 | 28S | 4659 | Ψ | 87 |

| 18S | 866 | Ψ | 88 | 28S | 1670 | Ψ | 96 | 28S | 3830 | Ψ | 92 | 28S | 4937 | Ψ | 81 |

| 18S | 867 | Gm | 28 | 28S | 1731 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 3832 | Ψ | 100 | 28S | 4966 | Ψ | 86 |

| 18S | 897 | Ψ | 23 | 28S | 1747 | Gm | 89 | 28S | 3846 | Am | 43 | 28S | 4975 | Ψ | 72 |

| 18S | 918 | Ψ | 42 | 28S | 1760 | Um | 70 | 28S | 3848 | Cm | 67 | ||||

| 18S | 966 | Ψ | 89 | 28S | 1766 | Ψ | 40 | 28S | 3863 | Ψ | 33 |

aThe abbreviations for nucleotides are as follows: Ψ, pseudouridine; Am, 2′-O-methyladenosine; Cm, 2′-O-methylcytidine; Gm, 2′-O-methylguanosine; Um, 2′-O-methyluridine; Ψm, 2′-O-methylpseudouridine; m1A, 1-methyladenosine; m62A, N6, N6-dimethyladenosine; m5C, 5-methylcytidine; m7G, 7-methylguanosine; m3U, 3-methyluridine; m6A, N6-methyladenosine; ac4C, N4-acetylcytidine; m1acp3Ψ, 1-methyl-3-(3-amino-3-carboxypropyl)pseudouridine.

Underline denotes the modified nucleotides newly identified in this study. The standard deviation of the values described here is expected to be around 2%, deduced from the average value of the standard deviation in previous SILNAS-based PTM quantitation (Taoka M, Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43: e115).

One of the most significant findings of this study is that the rRNA PTMs detected in TK6 cells did not differ significantly from those identified in other human cells, i.e., HeLa cells, where we determined ∼70% of all PTMs in the rRNAs (Supplementary Table S5), and induced pluripotent stem cells (Taoka et al., unpublished results), in terms of PTM types, sites, and the stoichiometry of modification at each site. This suggests that PTMs in human rRNAs have little polymorphism regarding the cell type. It should be also noted that human rRNAs contains many sequence variants (38). In fact, human TK6 cell used in this study contains five sequence variants including the one we used for the reference RNA. Although the variation includes base insertions, deletions and substitutions within ∼0.1% region of the whole sequence, all of the variation-containing RNase T1 fragments have been identified in this study and are found to contain no modified nucleosides (Supplementary Table S7). Thus, the variation in human rRNA sequence does not impact the current analysis.

Apart from the chemical analysis of PTMs of human rRNAs described above, Natchiar et al. recently reported the cryo-EM structure of the human 80S ribosome prepared from HeLa cell at ∼2.5 Å resolution (19). They visualized ∼136 PTMs among the rRNAs and claimed that there are many human-specific modifications that perhaps could inform the design of drugs that could selectively inhibit ribosome function in pathogens. The results of that cryo-EM study, however, are only partly consistent with those reported previously (4,5,20,21 and reference therein) and those we obtained during our MS-based analysis: namely, we estimated that only 78 of ∼136 PTMs (57%) visualized in the cryo-EM analysis of Natchiar et al. are supported by the MS analysis, whereas most others are found to be unmodified (Supplementary Table S8). Thus, the cryo-EM analysis of Natchiar et al. covered 34% of the total PTMs (78 of 228) identified in our MS-based analysis (Supplementary Table S8). Our analysis also revealed that all PTMs found in human rRNAs are typical of eukaryotic rRNAs, i.e., no human-specific PTMs were detected. Given that the results of the SILNAS-based PTM analysis of rRNAs in HeLa cell covering ∼70% of all PTMs showed that the modified nucleosides locate exactly at the same sites as in the TK6 rRNAs as described above (16,39), we suggest that the current single-particle cryo-EM technique needs to be improved for the detailed structural analysis at the ∼0.1 nm level and requires confirmation by a complementary technique such as MS.

According to the SILNAS-based quantitative analysis of the stoichiometry of PTMs at each site of human rRNAs, 172 of the 228 sites were almost fully modified (≥85%), whereas the others were modified to an extent between 5% and 85% (Table 1). Notably, we found that all of the partially modified sites reflect small nucleolar RNA–directed modifications, i.e. pseudouridylation, 2′-O-methylation, and base acetylation at C1337 in 18S rRNA (40). Although the biological relevance of this observation is unclear, indeed each of pseudouridylated and 2′-O-methylated sites of the rRNAs is sensitive to environmental stimuli that promote cellular stress, such as growth temperature in fission yeast (22). Moreover, cytidine acetylation at the corresponding position in fission yeast (C1297) also occurred partially, and yeast cells deficient in the responsible acetyltransferase encoded by Nat10 showed a slow-growth phenotype and were defective in forming 18S rRNA from the precursor rRNA (41,42), suggesting a conserved role for cytidine acetylation in ribosome biogenesis during the evolution of eukaryotes.

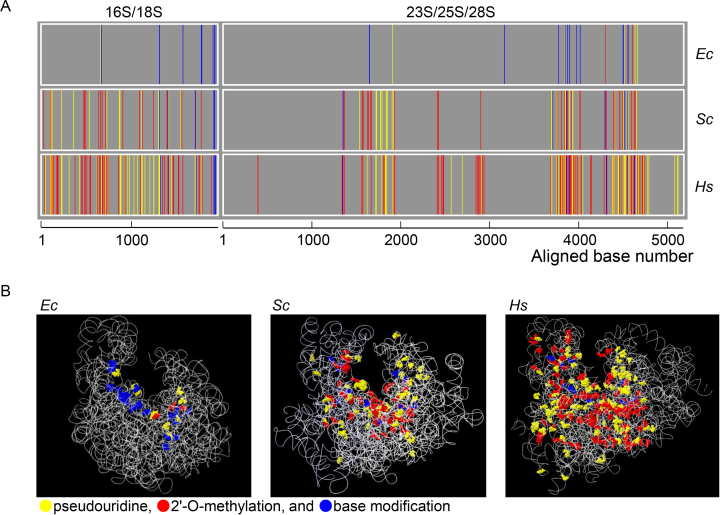

PTM clustering of rRNAs appears to have occurred during evolution

Although most PTMs of human rRNAs are typical of eukaryotic rRNAs and many are conserved in yeast, human rRNAs appear to accumulate much more modification sites (228 sites) than yeast rRNAs, e.g., 112 PTM for S. cerevisiae rRNAs (Supplementary Table S9). Furthermore, yeast rRNAs appear to have accumulated more modification sites than prokaryotic rRNAs, e.g., Escherichia coli has 11 modification sites in 16S rRNA and 25 in 23S rRNA (Figure 1). We found that this relatively greater number of PTMs is mostly attributable to increased pseudouridylation and 2′-O-methylation of the ribose moiety (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S7). In addition, most modification reactions occur in close proximity, forming clusters of modification sites along the rRNA chain as reported earlier by Decatur and Fournier (7); three large clusters (near positions 1600–1900, 3700–4000 and 4400–4700) and three small clusters (near positions 1300, 2400 and 2900) were detected both in the yeast 26S and human 28 rRNA. A similar type of PTM clustering also appears to have occurred in 16S/18S rRNAs during evolution (Figure 1). This appears to correlate with a rich-get-richer process or a power-law distribution (Supplementary Figure S8). For example, in biological networks, including metabolic networks (43–45), protein interactions (46), and phosphorylation (47), the power-law distribution confers functional advantages of robustness to environmental changes and tolerance to random mutations (48). Thus, we anticipate that, in human rRNAs, the clustering of PTMs might have increased the structural and functional stability of ribosomes during evolution. In this context, it should be noted that human 28S rRNA has acquired more PTMs around positions 450, 2500, 4100 and 5100 compared with the yeast counterpart, implying that these PTMs have a specific role in stabilizing the human ribosome and/or enhancing its function. On the other hand, a 3D overview of all modification sites in human rRNAs clearly indicates that most sites are concentrated in functionally important interior regions of the ribosome, including the peptidyl transferase center, the A, P and E sites for tRNA and mRNA binding, the polypeptide exit tunnel, and the interacting surfaces of the small and large subunits (Figures 1 and 2). Clearly, the PTM sites in human rRNAs expand from the interior to the exterior regions as compared with yeast rRNAs (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 1.

(A) One-dimensional PTM maps of the E. coli (Ec), budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Sc) and human (Hs) rRNAs. The PTM sites were plotted against rRNA sequences aligned by the sequence homology (shown in Supplementary Table S9) obtained by using the Clustal Omega software (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The PTM sites are colored yellow (pseudouridine), red (2′-O-methylated nucleoside), and blue (base-modified nucleoside). (B) Three-dimensional PTM maps of the Ec, Sc, and Hs ribosomes. The PTM sites were assigned to the three-dimensional structure of the rRNAs obtained from 4YBB.pdb (for Ec), 3U5B.pdb (Sc) and 4UG0.pdb (Hs). The RNA backbone is shown as a ribbon, and PTM sites are colored as in (A).

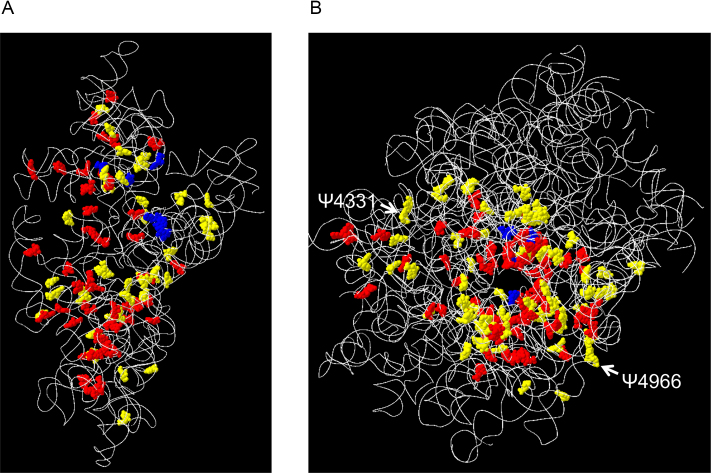

Figure 2.

The 3D PTM map of the small (A) and large (B) subunits of the human 80S ribosome. The PTM sites were assigned to the 3D structure of human rRNAs (4UG0.pdb). The RNA backbones and PTM sites are colored as in Figure 1B. White arrows indicate the positions of Ψ4331 and Ψ4966, which are less stoichiometrically modified in patients with DC.

Pseudouridylation at two specific sites of rRNA are significantly reduced in ribosomes of patients with familial DC

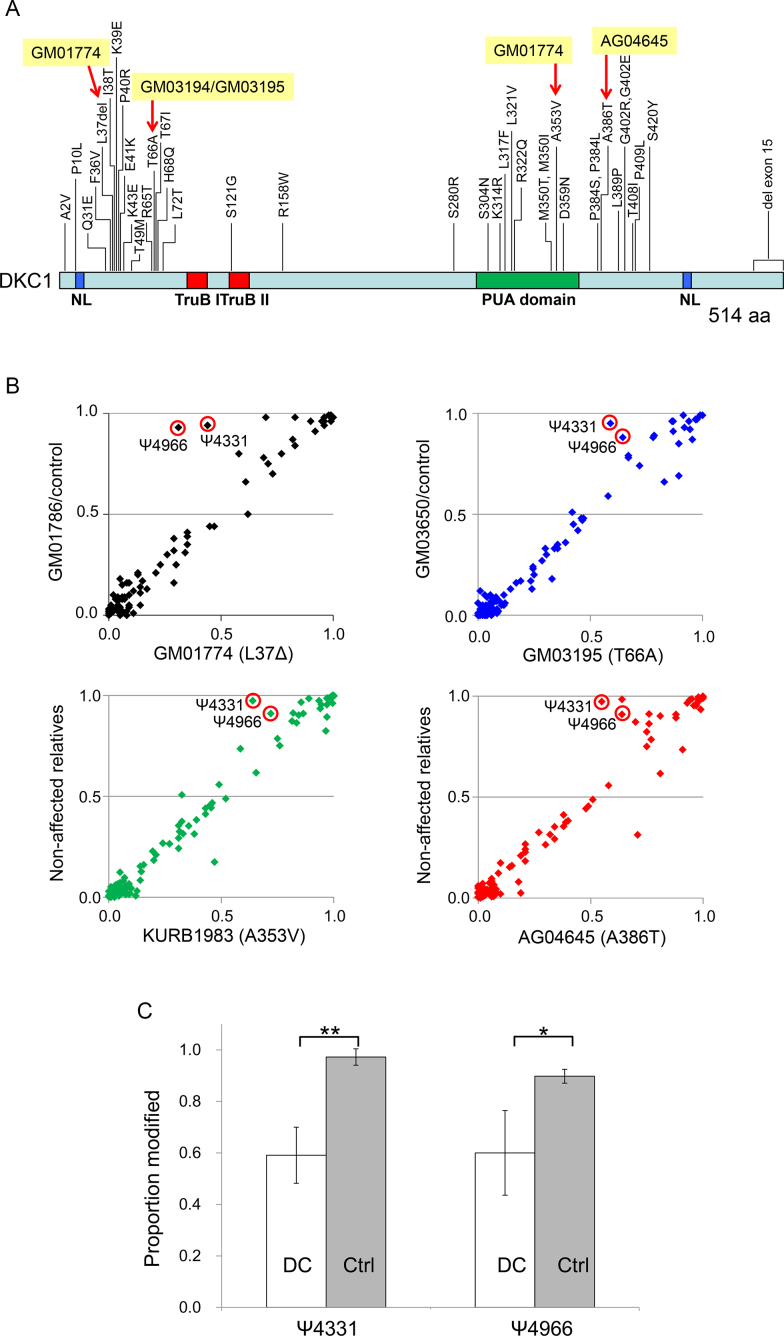

X-linked DC is a rare genetic disease characterized by defective tissue maintenance and cancer predisposition caused by a point mutation in the pseudouridine synthase gene DKC1 (49); because DKC1 is also a telomere maintenance factor, however, it remains unclear which DKC1 activity is primarily responsible for the pathogenesis of DC. The autosomal dominant types of DC are a consequence of mutations in the telomerase RNA TERC (50), implying that this form of the disease is caused by a defect in telomere maintenance, whereas the mutations found in the catalytic domain of DKC1 are associated with a more severe form of DC (51), implying that this form of the disease is caused by a defect in the rRNA pseudouridine synthase activity. To examine whether mutations in DKC1 affect the pseudouridylation of rRNAs, we performed SILNAS-based comprehensive quantification of PTMs in rRNA derived from DC patients. We cultured fibroblasts and B-lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from patients age 7–19 years old harboring four distinct mutations, namely del37L, A353V, T66A and A386T, located in the different domains of DKC1 pseudouridine synthase (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table S3); cells from relatives served as a reference. This approach identified and quantified ∼90% of the PTMs among the 5.8S, 18S and 28S rRNAs, which allowed for quantitative comparison of most rRNA PTMs from DC patients and relatives. Notably, the PTMs from nine individuals were strictly conserved with respect to not only the sites but also the stoichiometry of modification at each site (Supplementary Table S4), underscoring the paucity of PTM polymorphisms in human rRNAs. Thus, we propose that the rRNA PTMs are much more conservative than previously thought (16,39) and are tightly regulated, as noted in the PTM analysis of rRNAs derived from different cell types (Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 3.

SILNAS-based PTM analysis of rRNAs from cells derived from DC patients. (A) The positions of amino acid (aa) substitutions or deletions in DKC1 from DC patient cells. The nuclear localization signals (NL) and TruB and PUA domains of DKC1 are indicated. Red arrows denote mutations in patient rRNAs analyzed in this study. The figure was redrawn based on Vulliamy et al. (56) (http://telomerase.asu.edu/diseases.html). (B) Correlation between the stoichiometry of PTM in 28S rRNA from cells of DC patients and healthy controls. The PTMs in all rRNAs from the cells of five DC patients and four non-affected relatives were assessed with SILNAS (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). The four plots compare the stoichiometry of modification in 28S rRNA derived from four DKC1 mutant cell lines (del37L, A353V, T66A, A386T) vs. control lines, and a significant difference was detected for Ψ4331 and Ψ4966 (red circles). Note that the average stoichiometric value of non-affected relatives was used as the control for Patients KURB1983 and AG4645 because the cells of a relative were not available for Patients KURB1983 and AG4645. (C) Statistical significance of differences in pseudouridylation at positions 4331 and 4966 in 28S rRNA from DC patient cells. Each value represents the mean ± S.D. of five DC patients and four relatives (Ctrl). *P < 0.005, **P < 0.0005 (one-tailed Student's t-test).

Based on a detailed comparison of the stoichiometry of modification at each site, however, we detected relatively less pseudouridylation at positions 4331 and 4966 in 28S rRNA derived from DC patients (Figure 3B and Supplementary Table S4). The difference in each case (∼40%) appears to be statistically significant (Figure 3C) and evident in DC patients regardless of the mutation site in DKC1. According to the 3D structure of the ribosome, both Ψ4331 and Ψ4966 are located at the periphery of the large subunit rather than the interior, and thereby have potential roles in stabilizing the ribosome structure via interactions with ribosomal proteins (Figure 2). This raises a possibility that Ψ4331 and Ψ4966 alter internal ribosomal entry site-dependent RNA translation and translational fidelity (52), and the resulting fluctuations in protein synthesis may impair the function of hematopoietic stem cells (53) and cause DC symptoms (54). Whether the reduced pseudouridylation at those sites of rRNA has a role in DC pathogenesis remains unknown, but Ψ4331 and Ψ4966 may in fact serve as novel biochemical markers for early diagnosis of DC that complements the currently available indicators, e.g., a telomere length (55). Apparently, further studies on more DC cases are required to verify the results and possibilities described above. Nevertheless, the complete survey of rRNA PTMs provided by this study will serve as a resource for exploring the functional roles of rRNA PTMs and yield the most complete atomic model of human ribosome.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms C. Fujita for technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant for Core Research for Evolutionary Science and Technology (CREST) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Japan Science and Technology Agency for Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology [13415564]. Funding for open access charge: Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST); Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Khatter H., Myasnikov A.G., Natchiar S.K., Klaholz B.P.. Structure of the human 80S ribosome. Nature. 2015; 520:640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anger A.M., Armache J.P., Berninghausen O., Habeck M., Subklewe M., Wilson D.N., Beckmann R.. Structures of the human and Drosophila 80S ribosome. Nature. 2013; 497:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quade N., Boehringer D., Leibundgut M., van den Heuvel J., Ban N.. Cryo-EM structure of Hepatitis C virus IRES bound to the human ribosome at 3.9-A resolution. Nat. Commun. 2015; 6:7646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lestrade L., Weber M.J.. snoRNA-LBME-db, a comprehensive database of human H/ACA and C/D box snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006; 34:D158–D162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Incarnato D., Anselmi F., Morandi E., Neri F., Maldotti M., Rapelli S., Parlato C., Basile G., Oliviero S.. High-throughput single-base resolution mapping of RNA 2-O-methylated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:1433–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Machnicka M.A., Milanowska K., Osman Oglou O., Purta E., Kurkowska M., Olchowik A., Januszewski W., Kalinowski S., Dunin-Horkawicz S., Rother K.M.. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways–2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:D262–D267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Decatur W.A., Fournier M.J.. rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002; 27:344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noeske J., Wasserman M.R., Terry D.S., Altman R.B., Blanchard S.C., Cate J.H.. High-resolution structure of the Escherichia coli ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015; 22:336–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polikanov Y.S., Melnikov S.V., Soll D., Steitz T.A.. Structural insights into the role of rRNA modifications in protein synthesis and ribosome assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015; 22:342–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharma S., Lafontaine D.L.. ‘View from a Bridge’: A new perspective on eukaryotic rRNA base modification. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015; 40:560–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burakovsky D.E., Prokhorova I.V., Sergiev P.V., Milon P., Sergeeva O.V., Bogdanov A.A., Rodnina M.V., Dontsova O.A.. Impact of methylations of m2G966/m5C967 in 16S rRNA on bacterial fitness and translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:7885–7895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liang X.H., Liu Q., Fournier M.J.. rRNA modifications in an intersubunit bridge of the ribosome strongly affect both ribosome biogenesis and activity. Mol. Cell. 2007; 28:965–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baudin-Baillieu A., Fabret C., Liang X.H., Piekna-Przybylska D., Fournier M.J., Rousset J.P.. Nucleotide modifications in three functionally important regions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ribosome affect translation accuracy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:7665–7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kimura S., Suzuki T.. Fine-tuning of the ribosomal decoding center by conserved methyl-modifications in the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:1341–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Motorin Y., Helm M.. RNA nucleotide methylation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2011; 2:611–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McMahon M., Contreras A., Ruggero D.. Small RNAs with big implications: new insights into H/ACA snoRNA function and their role in human disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2015; 6:173–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sloan K.E., Warda A.S., Sharma S., Entian K.D., Lafontaine D.L.J., Bohnsack M.T.. Tuning the ribosome: The influence of rRNA modification on eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis and function. RNA Biol. 2017; 14:1138–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sergiev P.V., Aleksashin N.A., Chugunova A.A., Polikanov Y.S., Dontsova O.A.. Structural and evolutionary insights into ribosomal RNA methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018; 14:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Natchiar S.K., Myasnikov A.G., Kratzat H., Hazemann I., Klaholz B.P.. Visualization of chemical modifications in the human 80S ribosome structure. Nature. 2017; 551:472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krogh N., Jansson M.D., Hafner S.J., Tehler D., Birkedal U., Christensen-Dalsgaard M., Lund A.H., Nielsen H.. Profiling of 2′-O-Me in human rRNA reveals a subset of fractionally modified positions and provides evidence for ribosome heterogeneity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:7884–7895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carlile T.M., Rojas-Duran M.F., Zinshteyn B., Shin H., Bartoli K.M., Gilbert W.V.. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature. 2014; 515:143–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taoka M., Nobe Y., Hori M., Takeuchi A., Masaki S., Yamauchi Y., Nakayama H., Takahashi N., Isobe T.. A mass spectrometry-based method for comprehensive quantitative determination of post-transcriptional RNA modifications: the complete chemical structure of Schizosaccharomyces pombe ribosomal RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taoka M., Nobe Y., Yamaki Y., Yamauchi Y., Ishikawa H., Takahashi N., Nakayama H., Isobe T.. The complete chemical structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae rRNA: partial pseudouridylation of U2345 in 25S rRNA by snoRNA snR9. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:8951–8961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shalev-Benami M., Zhang Y., Rozenberg H., Nobe Y., Taoka M., Matzov D., Zimmerman E., Bashan A., Isobe T., Jaffe C.L.. Atomic resolution snapshot of Leishmania ribosome inhibition by the aminoglycoside paromomycin. Nat. Commun. 2017; 8:1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takashima Y., Sakuraba M., Koizumi T., Sakamoto H., Hayashi M., Honma M.. Dependence of DNA double strand break repair pathways on cell cycle phase in human lymphoblastoid cells. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2009; 50:815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ishikawa H., Yoshikawa H., Izumikawa K., Miura Y., Taoka M., Nobe Y., Yamauchi Y., Nakayama H., Simpson R.J., Isobe T.. Poly(A)-specific ribonuclease regulates the processing of small-subunit rRNAs in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:3437–3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Keka I.S., Mohiuddin, Maede Y., Rahman M.M., Sakuma T., Honma M., Yamamoto T., Takeda S., Sasanuma H.. Smarcal1 promotes double-strand-break repair by nonhomologous end-joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:6359–6372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yamauchi Y., Taoka M., Nobe Y., Izumikawa K., Takahashi N., Nakayama H., Isobe T.. Denaturing reversed phase liquid chromatographic separation of non-coding ribonucleic acids on macro-porous polystyrene-divinylbenzene resins. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013; 1312:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taoka M., Yamauchi Y., Nobe Y., Masaki S., Nakayama H., Ishikawa H., Takahashi N., Isobe T.. An analytical platform for mass spectrometry-based identification and chemical analysis of RNA in ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:e140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nakayama H., Yamauchi Y., Taoka M., Isobe T.. Direct identification of human cellular microRNAs by nanoflow liquid chromatography-high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry and database searching. Anal. Chem. 2015; 87:2884–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamauchi Y., Nobe Y., Izumikawa K., Higo D., Yamagishi Y., Takahashi N., Nakayama H., Isobe T., Taoka M.. A mass spectrometry-based method for direct determination of pseudouridine in RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 44:e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nakayama H., Akiyama M., Taoka M., Yamauchi Y., Nobe Y., Ishikawa H., Takahashi N., Isobe T.. Ariadne: a database search engine for identification and chemical analysis of RNA using tandem mass spectrometry data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Popova A.M., Williamson J.R.. Quantitative analysis of rRNA modifications using stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014; 136:2058–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ofengand J., Bakin A.. Mapping to nucleotide resolution of pseudouridine residues in large subunit ribosomal RNAs from representative eukaryotes, prokaryotes, archaebacteria, mitochondria and chloroplasts. J. Mol. Biol. 1997; 266:246–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maden B.E., Salim M.. The methylated nucleotide sequences in HELA cell ribosomal RNA and its precursors. J. Mol. Biol. 1974; 88:133–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lowe T.M., Eddy S.R.. A computational screen for methylation guide snoRNAs in yeast. Science. 1999; 283:1168–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jorjani H., Kehr S., Jedlinski D.J., Gumienny R., Hertel J., Stadler P.F., Zavolan M., Gruber A.R.. An updated human snoRNAome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:5068–5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Parks M.M., Kurylo C.M., Dass R.A., Bojmar L., Lyden D., Vincent C.T., Blanchard S.C.. Variant ribosomal RNA alleles are conserved and exhibit tissue-specific expression. Sci. Adv. 2018; 4:eaao0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xue S., Barna M.. Specialized ribosomes: a new frontier in gene regulation and organismal biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012; 13:355–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharma S., Yang J., van Nues R., Watzinger P., Kotter P., Lafontaine D.L.J., Granneman S., Entian K.D.. Specialized box C/D snoRNPs act as antisense guides to target RNA base acetylation. PLos Genet. 2017; 13:e1006804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li Z., Lee I., Moradi E., Hung N.J., Johnson A.W., Marcotte E.M.. Rational extension of the ribosome biogenesis pathway using network-guided genetics. PLoS Biol. 2009; 7:e1000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taoka M., Ishikawa D., Nobe Y., Ishikawa H., Yamauchi Y., Terukina G., Nakayama H., Hirota K., Takahashi N., Isobe T.. RNA cytidine acetyltransferase of small-subunit ribosomal RNA: identification of acetylation sites and the responsible acetyltransferase in fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e112156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fell D.A., Wagner A.. The small world of metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000; 18:1121–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jeong H., Tombor B., Albert R., Oltvai Z.N., Barabasi A.L.. The large-scale organization of metabolic networks. Nature. 2000; 407:651–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ravasz E., Somera A.L., Mongru D.A., Oltvai Z.N., Barabasi A.L.. Hierarchical organization of modularity in metabolic networks. Science. 2002; 297:1551–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jeong H., Mason S.P., Barabasi A.L., Oltvai Z.N.. Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature. 2001; 411:41–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yachie N., Saito R., Sugahara J., Tomita M., Ishihama Y.. In silico analysis of phosphoproteome data suggests a rich-get-richer process of phosphosite accumulation over evolution. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2009; 8:1061–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Przulj N. Protein-protein interactions: making sense of networks via graph-theoretic modeling. Bioessays. 2011; 33:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Calado R.T., Young N.S.. Telomere maintenance and human bone marrow failure. Blood. 2008; 111:4446–4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vulliamy T., Marrone A., Goldman F., Dearlove A., Bessler M., Mason P.J., Dokal I.. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 2001; 413:432–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita in all its forms. Br. J. Haematol. 2000; 110:768–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Penzo M., Rocchi L., Brugiere S., Carnicelli D., Onofrillo C., Coute Y., Brigotti M., Montanaro L.. Human ribosomes from cells with reduced dyskerin levels are intrinsically altered in translation. FASEB J. 2015; 29:3472–3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Signer R.A., Magee J.A., Salic A., Morrison S.J.. Haematopoietic stem cells require a highly regulated protein synthesis rate. Nature. 2014; 509:49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yu Y.T., Meier U.T.. RNA-guided isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine–pseudouridylation. RNA Biol. 2015; 11:1483–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Townsley D.M., Dumitriu B., Young N.S.. Bone marrow failure and the telomeropathies. Blood. 2014; 124:2775–2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vulliamy T.J., Marrone A., Knight S.W., Walne A., Mason P.J., Dokal I.. Mutations in dyskeratosis congenita: their impact on telomere length and the diversity of clinical presentation. Blood. 2006; 107:2680–2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.