Abstract

Purpose

To study the landscape of funding in intensive care research and assess whether the reported outcomes of industry-funded randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are more favorable.

Methods

We systematically assembled meta-analyses evaluating any type of intervention in the critical care setting and reporting the source of funding for each included RCT. Furthermore, when the intervention was a drug or biologic, we searched also the original RCT articles, when their funding information was unavailable in the meta-analysis. We then qualitatively summarized the sources of funding. For binary outcomes, separate summary odds ratios were calculated for trials with and without industry funding. We then calculated the ratio of odds ratios (RORs) and the summary ROR (sROR) across topics. ROR < 1 implies that the experimental intervention is relatively more favorable in trials with industry funding compared with trials without industry funding. For RCTs included in the ROR analysis, we also examined the conclusions of their abstract.

Results

Across 67 topics with 568 RCTs, 88 were funded by industry and another 73 had both industry and non-profit funding. Across 33 topics with binary outcomes, the sROR was 1.10 [95% CI (0.96–1.26), I2 = 1%]. Conclusions were not significantly more commonly unfavorable for the experimental arm interventions in industry-funded trials (21.3%) compared with trials without industry funding (18.2%).

Conclusion

Industry-funded RCTs are the minority in intensive care. We found no evidence that industry-funded trials in intensive care yield more favorable results or are less likely to reach unfavorable conclusions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00134-018-5325-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Meta-epidemiology, Industry-funded, Randomized controlled trials, Sponsorship

Introduction

Clinical trials funded by industry and those funded by non-profit institutions may differ in their results and conclusions [1–5]. Several evaluations have compared trials with and without industry funding on reported efficacy, harms, conclusions, and risk of bias [6]. Most of these studies addressed single or few topics and none focused on intensive care. Between 2006 and 2012, 33% of the trials registered on Clinicaltrials.gov were funded by industry [7], but industry overall spends more on clinical research than public funders [8] and has unavoidable financial incentives to get favorable conclusions.

Industry may interfere at all steps of the research pipeline, including production of evidence (both fundamental and clinical research) [9], evidence synthesis (including ghostwriting) [9–11], and decision-making [9]. For randomized controlled trials (RCTs), industry sponsors can influence study outcomes by various means: e.g., choosing inactive or strawman comparators [12] or selectively reporting favorable results with spin [13]. The degree of financial involvement also varies. Industry may be the only funder or one among multiple funders, or it may offer drug/placebo or technical support. However, it often remains unclear in published papers whether industry sponsors have exerted a catalytic, modest, or no influence on the paper. CONSORT requires reporting of funding sources and conflicts of interest [14], but reporting remains suboptimal [15]. There is even less transparency on industry-led ghostwriting of the published reports [16].

Intensive care research is often stated to be underfunded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) compared to the burden of critical illnesses on healthcare in the USA [17, 18] and similar issues exist also in other countries where intensive care is widely employed. Unmet needs raise the stakes for sponsors and manufacturers; yet little is known on the funding landscape of intensive care research. Here, we assessed to what extent critical care research (specifically RCTs) is funded by industry and whether there are clear differences in the results and conclusions of trials by different sponsors. Therefore, we conducted a meta-epidemiological overview of systematic reviews of RCTs conducted in critical care settings.

Methods

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

We searched PubMed (March 1, 2018) for meta-analyses and Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews (CDSRs) using the following keywords in their titles: respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, ventilation, ventilated, critical care, intensive care, septic shock, sepsis, fluid, fluid resuscitation, hydroxyethyl starch, or albumin (Supplementary file). Recent articles published online between 2015 and 2018 were screened; for older reviews published pre-2015, only CDSRs were screened because the source of funding for included trials is rarely reported in meta-analyses published in journals.

After removing duplicates, two reviewers (PJ and IAC) screened titles/abstracts and, if needed, full texts for eligibility. Systematic reviews that included meta-analyses of RCTs evaluating an intervention in the critical care setting were eligible if they also reported funding source(s) for each included RCT. When study-level funding information was unavailable in the systematic review, we perused the full text of each RCT to identify its funding whenever the interventions pertained to drugs or biologics (excluding supplements, fluids, antiseptics, probiotics), since these interventions are likely to have interested sponsors. Reviews of non-randomized studies and those without meta-analysis were excluded.

Data extraction

For each eligible review, we screened all RCTs included in the meta-analyses to determine funding sources: industry funding only; no industry funding; mixed sources of funding (industry and non-profit institutions); intervention supplied by industry; and not reported. If not available or unclear in the systematic review, the information was extracted from the full-text RCT article. For overlapping meta-analyses, we retained the most recent one, or the largest, when publication years were identical.

For meta-analyses including both RCTs with industry funding and RCTs without industry funding and using primary binary outcomes, we extracted information on setting (ICU, surgical ICU, mixed), population (preterm, infant, child, adult), type of the intervention (device, pharmacological, procedure), type of comparator (active, placebo, no intervention), and number of primary outcome events per arm. Whenever multiple primary outcomes existed or no single outcome was clearly identified as such, we selected the primary outcome with the largest number of included studies (in ties, largest sample size; and further ties, largest number of events).

For RCTs funded by industry (fully or mixed source) or supplied by industry, we identified whether interventions involved in the comparison were manufactured by the industry sponsor. Three scenarios were identified: one arm of the comparison contains a sponsor-manufactured intervention (SMI), both arms contain SMIs, and none of the arms contain SMIs. All comparisons were coined so that experimental arms were always an SMI versus a control. When both arms contained SMIs, the SMI considered as the experimental arm was chosen to be the most expensive one, and, when both arms contained equally expensive interventions or this was unclear, the SMI considered the experimental intervention was chosen to be the most recent one (as suggested by the original article). When trials were industry-funded but had no SMI involved in the comparison that we examined, they were excluded from quantitative analysis as they are not informative about sponsor bias.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Sources of funding were summarized across all eligible topics. For topics where trials with or without industry funding could be compared for binary outcomes, we prespecified two large categories in the primary analysis: with industry funding (industry only or mixed) versus without industry funding (non-profit institution and only intervention supplied by industry). RCTs without reported funding were excluded.

For each topic that included both trials with and without industry funding, separate summary odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the two categories of funding using random-effects model inverse variance weighting. In trials with zero event cells in the 2 × 2 table, a standard 0.5 correction was added [19]. For consistency, intervention and outcome data were coded so that OR < 1 indicates that the experimental SMI-containing intervention is better than the control.

To compare the relative treatment effect of RCTs with versus without industry funding, we calculated the ratio of odds ratios (RORs) for each topic, the summary OR of trials with industry funding divided by the summary OR of trials without industry funding. ROR < 1 implies the experimental intervention is relatively more favorable in trials with industry funding compared with trials without industry funding. We then calculated the summary ROR (sROR) across all topics using fixed effect [20] and random effects [21]. We assessed between-topic heterogeneity using I2 and its 95% confidence interval (CI) and between-topic variance τ2 [22]. We also assessed the magnitude of the difference by checking how often OR estimates with and without industry funding differed by twofold or more (ROR ≥ 2 or ≤ 0.5).

We conducted sensitivity analyses including only mortality outcomes; recoding trials for which the intervention was supplied by industry as “with industry funding”; excluding trials with 0 events in both arms; and retaining only trials with one SMI versus a control (excluding trials supplied by industry and trials with SMIs in both arms).

To explore the influence of trials not reporting their funding, we carried out secondary analyses comparing these trials versus trials with industry funding and trials not reporting their funding versus trials without industry funding. We also compared industry-funded and not reported trials combined together versus trials without industry funding. As previously, for all secondary analyses the sRORs were also calculated using fixed effect and random effects and I2 and τ2 were also assessed.

Conclusions of RCTs

In a further exploratory analysis, we evaluated the conclusions of the abstracts of the trials with industry funding and of those without industry funding for topics that were eligible for ROR analyses. Conclusions were considered as “negative” (unfavorable) if trials concluded that the experimental SMI was less effective, more harmful or not more effective (for superiority trials) without mentioning any potential positive trade-offs [e.g., good safety, lesser cost, possible benefit in subgroups/specific patients, worth studying further (in more long-term and/or larger studies) for potential benefits] or it was squarely stated that it is not recommended. All other scenarios were classified as “positive” conclusions, including those where the experimental SMI was equally effective as an active comparator, those where positive trade-offs were mentioned, and those where it was more effective than comparators.

Results were reported in 2 × 2 tables. We calculated the arcsine difference of having a negative conclusion for each topic and then the summary arcsine (AS) estimate across topics using random effects. The arcsine transformation enables one to obtain a more robust estimate while including 0 cells in the analysis without continuity corrections [23]. AS > 0 implies that conclusions are more favorable in industry-funded trials.

Results

Search results

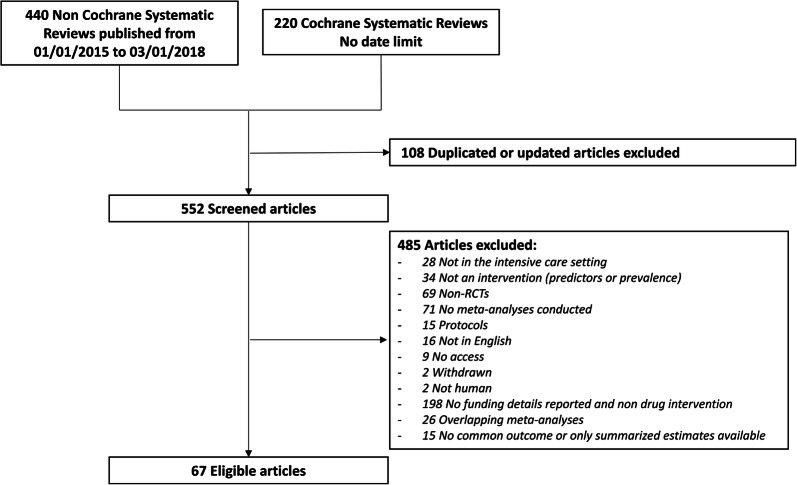

The search on PubMed yielded 220 CDSRs and 440 meta-analyses published in journals in 2015–2018 (Fig. 1). After exclusions, 67 systematic reviews were eligible of which 37 reported the sources of funding of the included RCTs and 30 did not but evaluated a drug intervention and for which we could retrieve sources of funding of each trial by perusing the respective full-text articles of RCTs. Across the 67 topics, there were a total of 568 RCTs. Of those, 88 (15.5%) were funded by industry, 73 (12.9%) were funded by both industry and other funding sources, 167 (29.4%) had only not-for-profit funding, 20 (3.5%) had not-for-profit funding but were supplied by industry, 144 (25.4%) did not report sources of funding, and 76 (13.4%) were excluded because of non-English language or access barrier (Table 1). Nine RCTs stated that they did not receive any funding for their study, and we have included them among the trials with only not-for-profit funding, since unavoidable expenses (e.g., personnel salary and overheads) can be assumed to have been covered by investigators and/or their institutions.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the literature search and screening

Table 1.

General characteristics

| At topic level | All 67 eligible topics | The 33 topics included in the sROR analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N =67 | N =33 | |||

| Type of interventions | ||||

| Drug intervention | 45 | 67.2% | 24 | 72.7% |

| Devices | 12 | 17.9% | 5 | 15.2% |

| Procedure | 10 | 14.9% | 4 | 12.1% |

| Type of comparator | ||||

| Active | 34 | 50.7% | 13 | 39.4% |

| Placebo or no intervention | 31 | 46.3% | 18 | 54.5% |

| Active, placebo or no intervention | 2 | 3% | 2 | 6.1% |

| At RCT level | All 67 eligible topics | The 33 topics included in the sROR analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N =568 | N =363 | |||

| Number of RCTs by sponsors | ||||

| Industry | 88 | 15.5% | 61 | 16.8% |

| Industry and non-profit organization | 73 | 12.9% | 52 | 14.3% |

| Non-profit organization | 167a | 29.4% | 100b | 27.5% |

| Supplied by industry | 20 | 3.5% | 13 | 3.6% |

| NR | 144 | 25.4% | 104 | 28.7% |

| NA | 76 | 13.4% | 33 | 9.1% |

| Population included in RCTs | ||||

| Adults | 464 | 81.7% | 286 | 78.8% |

| Children | 16 | 2.8% | 9 | 2.5% |

| Neonates | 29 | 5.1% | 21 | 5.8% |

| Preterm | 17 | 3% | 17 | 4.7% |

| NR | 42 | 7.4% | 30 | 8.3% |

| Number of subjects included | ||||

| Median (interquartile range) | 63 (40–133) | 71 (41–172) | ||

| Total included | 92,034 | 71,283 | ||

| Industry | 29,029 | 23,047 | ||

| Industry and non-profit organization | 15,038 | 14,068 | ||

| Non-profit organization | 26,783 | 18,497 | ||

| Supplied by industry | 3393 | 2821 | ||

| NR | 11,555 | 9125 | ||

| NA | 6236 | 3725 | ||

NR not reported, NA original article not accessible or not in English

aNine of which reported that they did not receive any funding to conduct their trial

bSix of which reported that they did not receive any funding to conduct their trial

Topics that did not have both trials with and without industry funding

Twenty-five otherwise eligible topics could not be assessed for a comparison of trials with versus without industry funding because they only included trials with the same source of declared funding (Table 2). For 17 topics none of the trials had industry funding, for one topic all the trials had industry funding, and for another one all trials were funded both by industry and not-for-profit sources. The 25 topics include a total of 113 RCTs of which 20.3% (23/113) did not report their source of funding.

Table 2.

Topics reporting the same source of funding across all randomized controlled trials with declared funding

| Author | Year | Indication | Outcome | Funding type | Total trials included in meta-analysis | Trials with no reported funding | Trials with access barrier | Total sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monro-Somerville | 2017 | Effect of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy on mortality and intubation rate in acute respiratory failure | Hospital mortality | Industry | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1932 |

| Stephens | 2018 | Early sedation depth in mechanically ventilated patients | Mortality | Industry and non-profit | 2 | 0 | 0 | 97 |

| Shah | 2017 | Inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in ventilated very low birth weight preterm neonates | BPD at 36 weeks | Supplied by industry | 3 | 0 | 0 | 429 |

| Afshari | 2017 | Aerosolized prostacyclins for acute respiratory distress syndrome | Overall mortality | Non-profit | 2 | 0 | 0 | 81 |

| Alarcon | 2017 | Elevation of the head in people with severe traumatic brain injury | Mortality at the end of study follow-up | Non-profit | 3 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Avni | 2015 | Vasopressors for the treatment of septic shock | 28-day mortality | Non-profit | 11 | 2 | 6 | 1718 |

| Borthwick | 2017 | High-volume hemofiltration for sepsis | Mortality | Non-profit | 2 | 0 | 0 | 156 |

| Bradt | 2014 | Music interventions for mechanically ventilated patients | State anxiety | Non-profit | 5 | 2 | 0 | 288 |

| Chacko | 2015 | Pressure-controlled versus volume-controlled ventilation for acute respiratory failure due to acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome | Mortality in hospital | Non-profit | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1089 |

| Dervan | 2017 | Methadone to facilitate opioid weaning in pediatric critical care patients | Proportion developing withdrawal | Non-profit | 2 | 1 | 0 | 115 |

| Hu | 2015 | Non-pharmacological interventions for sleep promotion | Total sleep time | Non-profit | 2 | 1 | 0 | 116 |

| Huang | 2017 | Dexmedetomidine for one-lung ventilation in adults undergoing thoracic surgery | Intraoperative oxygenation index | Non-profit | 7 | 0 | 4 | 269 |

| Korang | 2016 | Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for acute asthma in children | Serious adverse events | Non-profit | 2 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| Morag | 2016 | Cycled light for preterm and low birth weight infants | Daily weight gain during neonatal care | Non-profit | 2 | 0 | 0 | 128 |

| Pandor | 2015 | Pre-hospital noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure | Mortality | Non-profit | 10 | 2 | 0 | 800 |

| Rose | 2017 | Cough augmentation techniques for extubation or weaning | Extubation success | Non-profit | 2 | 1 | 0 | 95 |

| Stuani | 2017 | Underfeeding versus full enteral feeding in critically ill patients with acute respiratory failure | Overall mortality | Non-profit | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1532 |

| Wu | 2015 | Albuterol in the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome | Mortality | Non-profit | 3 | 0 | 0 | 646 |

| Yang | 2017 | Early application of low-dose glucocorticoid improves acute respiratory distress syndrome | Mortality | Non-profit | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1218 |

| Faria | 2015 | Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for acute respiratory failure following upper abdominal surgery | Rate of tracheal intubation | NR | 2 | 2 | 0 | 269 |

| Peng | 2017 | Delirium risk of dexmedetomidine and midazolam | Incidence of delirium | NR | 6a | 1 | 5 | 356 |

| Suresh | 2001 | Superoxide dismutase for preventing chronic lung disease in mechanically ventilated preterm infants | Death before discharge | NR | 2 | 2 | 0 | 78 |

| Wang | 2015 | Mannitol for acute severe traumatic brain injury | Mortality | NR | 2 | 2 | 0 | 53 |

| Liu | 2016 | Thymosin alpha1 for sepsis | 28-day mortality | NA | 10a | 0 | 10 | 530 |

| Zheng | 2018 | Xuebijing combined with ulinastatin for patients with sepsis | Mortality | NA | 11a | 0 | 11 | 741 |

References of the reviews are available in the supplementary information

NA original article not accessible or not in English

aAll included trials in the reviews were in Chinese

Topics where the industry sponsor did not manufacture any of the compared interventions

In another two topics, both trials with and without industry funding were available, but the industry funder did not manufacture any of the interventions for the comparison that we assessed. In one case, we were interested in the comparison of midazolam versus placebo, but an AstraZeneca-funded trial included a third arm of morphine (manufactured by the company) (eTable 1). Four other trials in other topics did not have SMIs in the two compared arms, but for their topics there existed also other industry-funded RCTs involving SMIs in the comparisons (eTable 1).

Topics using a continuous outcome

An additional seven topics were excluded from the ROR analysis because they only had primary continuous outcomes, covering 79 RCTs of which 35 were with industry funding (fully and mixed sources) and 22 were without industry funding (non-profit and supplied by industry) (eTable 2). The outcomes assessed were ventilation duration and other related outcomes such as weaning time or ICU length-of-stay and biological measurement such as cytokine levels.

Trials included in the ROR analyses

Thirty-three topics covering 363 RCTs were included in the comparison of the relative treatment effect of trials with versus those without industry funding. Their summary characteristics appear in Table 1 and detailed topic-specific results appear in Table 3. Out of the 126 RCTs with a connection with industry (fully funded, mixed source, or supplied by industry), 113 had only one SMI in the comparison and 13 had both arms with SMIs (in 5/13 trials the comparison involved a combination of two drugs versus a single drug by the same sponsor; in 5/13 trials the comparison addressed strategies of ventilation, tracheostomy, antibiotics, or sedation and the sponsor manufactured ventilators, tracheostomy equipment, antibiotics, and sedatives, respectively; in 2/13 trials the sponsor manufactured the fluids compared head-to-head; in the remaining trial, two companies sponsored the trial comparing their products head-to-head) (eTable 1).

Table 3.

Individual ROR and OR with and without industry funding for each topic

| Author | Year | Indication | SMI | Control | Outcome | Trials with industry funding | Trials without industry funding | ROR p value | ROR | OR with industry funding | OR without industry funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aitken | 2015 | Mechanical ventilated | Protocol-directed sedation | Non-protocol-directed sedation | Hospital mortality | 1 | 1 | 0.21 | 1.56 (0.78; 3.15) | 1.21 (0.72; 2.04) | 0.78 (0.49; 1.24) |

| Andriolo | 2017 | Sepsis | Procalcitonin-guided algorithm | No intervention | Mortality at longest FU | 3 | 1 | 0.69 | 1.21 (0.47; 3.09) | 1.03 (0.65; 1.65) | 0.86 (0.38; 1.94) |

| Barrington | 2017 | Respiratory failure neonates | Nitric oxide | Placebo or no intervention | Death before hospital discharge | 3 | 6 | 0.96 | 1.02 (0.44; 2.38) | 0.97 (0.49; 1.94) | 0.95 (0.58; 1.55) |

| Barrington | 2017 | Respiratory failure preterm | Nitric oxide | Placebo or no intervention | Death before hospital discharge | 9 | 4 | 0.50 | 1.2 (0.71; 2.04) | 1.05 (0.82; 1.36) | 0.88 (0.55; 1.4) |

| Bednarczyk | 2017 | Fluid resuscitation | Dynamic assessment | No intervention | Mortality | 5 | 7 | 0.66 | 1.24 (0.47; 3.26) | 0.66 (0.28; 1.58) | 0.53 (0.35; 0.82) |

| Beitland | 2015 | Adult ICU patients | Low molecular heparin | Unfractionated heparin | Any deep vein thrombosis | 2 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.9 (0.37; 2.17) | 0.76 (0.33; 1.77) | 0.85 (0.67; 1.07) |

| Bellu | 2008 | Mechanically ventilated infants | Opioids | Placebo or no intervention | Neonatal mortality | 1 | 3 | 0.21 | 0.13 (0.01; 3.03) | 0.16 (0.01; 3.51) | 1.19 (0.81; 1.73) |

| Busani | 2016 | Septic shock | Polyclonal intravenous immunoglobulin | Fluids or no intervention | Mortality | 6 | 2 | 0.29 | 3.8 (0.32; 45.2) | 0.91 (0.65; 1.27) | 0.24 (0.02; 2.77) |

| Fujii | 2018 | Sepsis and septic shock | Polymyxin B-immobilized hemoperfusion | No intervention | 28-day mortality | 4 | 1 | 0.56 | 1.93 (0.21; 17.34) | 1.07 (0.68; 1.7) | 0.56 (0.06; 4.76) |

| Gebistorf | 2016 | ARDS child and adult | Nitric oxide | Placebo or no intervention | Overall mortality | 5 | 5 | 1.00 | 1 (0.6; 1.67) | 1.06 (0.77; 1.45) | 1.06 (0.71; 1.58) |

| Gillies | 2017 | Mechanically ventilated adults | Heated humidifiers | Heat and moisture exchangers | Artificial airway occlusion | 5 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.28 (0.01; 7.79) | 2.04 (0.48; 8.72) | 7.15 (0.37; 139.77) |

| Guay | 2015 | Intraoperative acute lung injury in adults | Low tidal volume ventilation | High tidal volume ventilation | Mortality within 30 days after the surgery | 1 | 7 | 0.62 | 2.82 (0.05; 159.58) | 1.9 (0.04; 100.63) | 0.68 (0.32; 1.42) |

| Kuriyama | 2015 | Mechanically ventilated adults | Closed tracheal suctioning systems | Open tracheal suctioning systems | Incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia | 2 | 3 | 0.29 | 2.69 (0.43; 16.72) | 0.64 (0.34; 1.19) | 0.24 (0.04; 1.31) |

| Liberati | 2009 | Adult ICU patients | Antibiotics | No prophylaxis | Mortality | 9 | 2 | 0.51 | 0.73 (0.29; 1.83) | 0.83 (0.69; 1) | 1.13 (0.46; 2.78) |

| Liu | 2017 | Sepsis | Ulinastatin combined with thymosin alpha2 | Placebo or no intervention | 28-day mortality | 1 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.69 (0.17; 2.85) | 0.31 (0.09; 1.02) | 0.45 (0.21; 0.95) |

| Lu | 2017 | Sepsis | Omega-3 | Placebo | Mortality | 6 | 3 | 0.72 | 1.25 (0.39; 3.99) | 0.87 (0.52; 1.48) | 0.7 (0.25; 1.98) |

| Moeller | 2016 | Resuscitation | Gelatin-containing plasma expanders | Crystalloids or albumin | Mortality | 4 | 5 | 0.86 | 1.06 (0.56; 1.98) | 1.4 (0.83; 2.37) | 1.32 (0.94; 1.87) |

| Nagendran | 2017 | ARDS | Statins | Placebo | 28-day mortality | 1 | 4 | 0.91 | 1.04 (0.58; 1.84) | 1.11 (0.79; 1.56) | 1.07 (0.67; 1.71) |

| Osadnik | 2017 | Acute hypercapnic respiratory failure COPD adults | Noninvasive ventilation | No intervention | Endotracheal intubation | 1 | 9 | 0.16 | 0.17 (0.02; 1.96) | 0.05 (0; 0.54) | 0.29 (0.19; 0.43) |

| Porhomayon | 2015 | ICU survivors | Light sedation | Heavy or standard sedation | Delirium | 2 | 5 | 0.75 | 1.26 (0.32; 4.99) | 1.02 (0.33; 3.18) | 0.81 (0.37; 1.77) |

| Putzu | 2017 | ARD and sepsis in adults | Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration | No intervention | Mortality at longest follow-up | 2 | 2 | 0.95 | 0.87 (0.02; 42.85) | 0.27 (0.01; 11.97) | 0.31 (0.13; 0.76) |

| Serpa | 2017 | Resuscitation in adults | Balanced saline | Isotonic saline | In-hospital mortality | 2 | 2 | 0.88 | 0.84 (0.08; 8.52) | 0.87 (0.65; 1.17) | 1.03 (0.1; 10.26) |

| Shah | 2017 | Chronic lung disorders in infants | Corticosteroids | Placebo or no intervention | Chronic lung disease at 36 weeks post-menstrual age (among survivors) | 2 | 2 | 0.39 | 0.74 (0.38; 1.46) | 0.62 (0.46; 0.85) | 0.83 (0.46; 1.53) |

| Siempos | 2015 | Mechanical ventilated | Early trachesotomy | Late tracheostomy | Mortality | 1 | 6 | 0.01 | 0.35 (0.15; 0.81) | 0.29 (0.14; 0.61) | 0.82 (0.58; 1.16) |

| Sjovall | 2017 | Sepsis | Combination of antibiotics | One antibiotic | All-cause mortality | 7 | 1 | 0.92 | 1.02 (0.66; 1.58) | 1.18 (0.92; 1.52) | 1.16 (0.81; 1.66) |

| Sole-Lleonart | 2017 | Mechanical ventilated | Nebulized antibiotics | Intravenous antibiotics | Nephrotoxicity | 1 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.05 (0; 1.21) | 0.06 (0; 1.24) | 1.18 (0.47; 2.97) |

| Sud | 2016 | ARDS | High frequency oscillatory ventilation | Conventional or pressure controlled ventilation | Hospital or 30-day mortality | 4 | 3 | 0.21 | 2.48 (0.61; 10.19) | 1.03 (0.55; 1.94) | 0.41 (0.12; 1.46) |

| Umemura | 2016 | Sepsis | Anticoagulants | Placebo or no intervention | Mortality | 9 | 7 | 0.87 | 1.03 (0.75; 1.41) | 0.96 (0.87; 1.07) | 0.94 (0.7; 1.26) |

| Volbeda | 2015 | Sepsis | Corticosteroids | Placebo or no intervention | Mortality | 8 | 10 | 0.04 | 1.49 (1.02; 2.17) | 1.12 (0.86; 1.46) | 0.75 (0.57; 0.99) |

| Wang | 2017 | Septic shock | Levosimendan | Dobutamine, placebo or no intervention | Mortality | 1 | 4 | 0.04 | 2.54 (1.06; 6.07) | 1.23 (0.86; 1.77) | 0.49 (0.22; 1.07) |

| Zhang | 2015 | Sepsis | Antipyretic therapy | Placebo or no intervention | Mortality | 2 | 2 | 0.75 | 1.45 (0.15; 14.47) | 0.96 (0.11; 8.64) | 0.66 (0.34; 1.3) |

| Zhang | 2017 | ARDS | N-Acetylcysteine | Placebo | Short-term mortality | 3 | 1 | 0.10 | 4.82 (0.76; 30.69) | 0.8 (0.38; 1.71) | 0.17 (0.03; 0.9) |

References of the reviews are available in the supplementary information

ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, FU follow-up, ICU intensive care unit

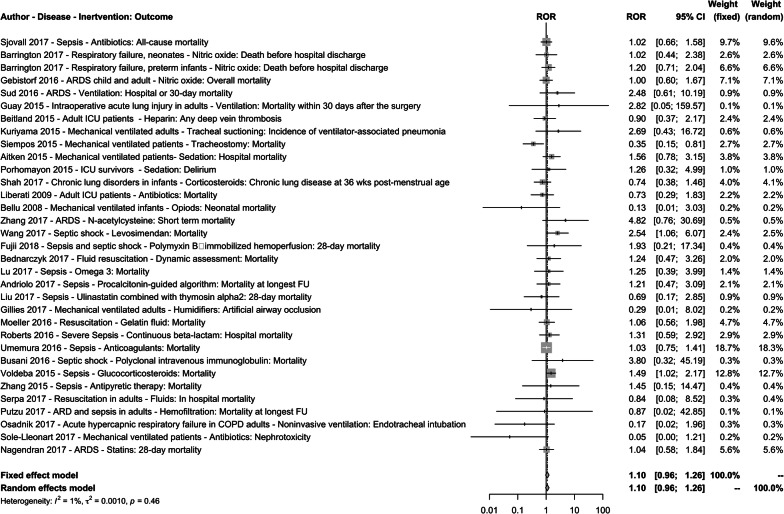

Primary analysis

The sROR across the 33 topics was 1.10 [95% CI (0.96; 1.26)] with no strong evidence of heterogeneity [I2 = 1%, 95% CI (0–40%), τ2 = 0.001, p value = 0.46] (Table 4 and Fig. 2). Within single topics, the 95% CIs of ROR excluded 1.00 in three topics [24–26]. Early tracheotomy significantly reduced mortality in a trial funded by a manufacturer of tracheotomy equipment [OR 0.29; 95% CI (0.14–0.61)] while there was a non-significant reduction in trials without industry funding [OR 0.82; 95% CI (0.58–1.16)] [24]. Conversely, corticosteroids [26] and levosimendan [25] for sepsis and septic shock reduced mortality in trials without industry funding [OR 0.49; 95% CI (0.22–1.07) and OR 0.75; 95% (0.57–0.99), respectively] while there was a non-significant increase in deaths in trials with industry funding [OR 1.23; 95% CI (0.86–1.77) and OR 1.12; 95% (0.86–1.46), respectively].

Table 4.

Summary RORs for all analysis

| Topics | N trials with industry funding | N trials without industry funding | sROR random effects | I2 (%; 95% CI) | τ2 | sROR fixed effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis | 33 | 113 | 113 | 1.10 (0.96; 1.26) | 1% (0%; 40%) | 0.001 | 1.10 (0.96; 1.26) |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||||||

| Mortality outcomes only | 26 | 100 | 90 | 1.14 (0.98; 1.31) | 0% (0%; 38%) | 0 | 1.14 (0.98; 1.31) |

| Supplied by industry merged with industry-funded trials | 32 | 118 | 100 | 1.12 (0.9; 1.4) | 36% (1%; 58%) | 0.109 | 1.17 (1.01; 1.36) |

| Without 0 events in both arms | 32 | 106 | 101 | 1.10 (0.95; 1.27) | 2% (0%; 41%) | 0.0035 | 1.10 (0.96; 1.26) |

| Without trials supplied by industry and without trials with SMI in both arms | 28 | 102 | 85 | 1.22 (1.02; 1.45) | 3% (0%; 44%) | 0.0065 | 1.22 (1.03; 1.44) |

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the comparison of with versus without industry funding. ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, FU follow-up, ICU intensive care unit

For seven topics, the point estimates of the ROR indicated a relative difference between with and without industry funding trials of at least twofold. Five topics had an ROR ≤ 0.5 [24, 27–30] while six topics had an ROR ≥ 2 [25, 31–35]. Uncertainty in the ROR estimates was typically substantial.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analysis excluding trials supplied by industry and trials with an SMI in both arms of the comparison resulted in sROR = 1.22 [95% CI (1.02–1.45)] with significantly more favorable outcomes in trials without industry funding compared with trials with industry finding. There was no evidence of heterogeneity [I2 = 3%, 95% CI (0–44%), τ2 = 0.0065, p value = 0.42]. The other sensitivity analyses did not substantially change the results observed in the primary analysis (Table 4, eFig. 3 and eTable 3).

Secondary analyses

Trials that did not report their source of funding had an sROR of 0.88 [95% CI (0.71–1.07); I2 = 0%, 95% CI (0–30%)] versus trials without industry funding. Trials that did not report their source of funding also had an sROR of 0.88 [95% CI (0.74–1.04); I2 = 15%, 95% CI (0–48%)] versus trials with industry funding.

For trials that did not report their source of funding or had industry funding versus those without industry funding, the sROR was 0.98 [95% CI (0.85–1.13); I2 = 1%, 95% CI (0–45%)]. Results of secondary analyses are available in eTable 4 and eFig. 4.

Conclusions in abstracts

Excluding seven trials without abstracts and one that did not conclude on the SMI, 23 among 108 RCTs with industry funding (21.3%), as opposed to 20 among 110 RCTs (18.2%) without industry funding had negative conclusions (as defined in the “Methods” section). The AS estimate of having negative conclusion with versus without industry funding was 0.04, 95% CI (− 0.09 to 0.17).

Discussion

Randomized controlled trials in the intensive care setting seem to be led primarily by public and non-profit institutions while a sizeable minority has been funded by industry. Evidence on several clinically important topics includes no RCTs sponsored by industry. Topics such as assessing head elevation for severe brain injury [36], music to calm mechanically ventilated patients [37], cycled lights in neonatal intensive care units [38], or cough augmentation techniques for extubation [39] are procedures where the lack of industry funding is easily explained. Such procedures do not necessarily involve equipment or products manufactured by the biopharmaceutical, biotechnology, or other health-related industry. However, in cases such as low-dose corticosteroids for acute respiratory distress syndromes we cannot exclude the possibility that the trials not reporting their source of funding were potentially funded by industry, but this had not been disclosed [40]. We found only one topic where all the available published trials with reported funding disclosed industry support, the evaluation of high-flow nasal cannula in adult acute respiratory failure [41]. In the RCTs funded by industry, the typical pattern was comparison of an SMI versus a control. However, we also observed some variations, e.g., where companies sponsored trials in which both arms included their sponsored products, either as part of the comparison of interest or as backbone treatment given to all patients. As shown before, these trial designs promote the interests of the sponsor regardless of the results [12]. Head-to-head comparisons of products by different sponsors co-sponsoring the same trial are very rare [12, 42].

On average, our primary analysis did not show more favorable treatment effects for the primary outcome in trials with versus without industry funding. One sensitivity analysis even showed significantly less favorable results for trials with industry funding. The large CIs for many of the RORs at the topic level and the twofold difference in effect sizes for 11 topics highlight substantial remaining uncertainty. Those results have to be interpreted cautiously, because most trials had a small sample size (median of 71 participants). This fact, combined with the small number of events in our included RCTs, could explain the absence of notable statistical heterogeneity in our results; lack of power to detect heterogeneity may have resulted in low I2 estimates [43]. The preponderance of small trials is very common across diverse medical fields [44]. Small trials leave large uncertainty and it is quite easy to manipulate their results (based on diverse analytical choices adding degrees of freedom on aspects that are not fully covered by study registration and prespecified, publically available protocols) [45] and, even more, their conclusions.

Only a small minority of the evaluated trials reached clearly unfavorable conclusions for the experimental intervention. This suggests that investigators and sponsors are unwilling to deliver a clear “negative” message, even though the majority of tested interventions in intensive care settings fail to deliver [46]. Many trials find no benefits for the primary outcome, but may still report favorable trends for secondary outcomes, subgroups or specific patients, or may conclude that further perusal of the intervention may eventually identify benefits. The proportion of trials with negative conclusions was similar in industry-funded trials and those without industry funding.

Multiple other evaluations have tried to assess whether industry-funded trials yield more favorable efficacy results and conclusions [6]. None of them have focused on intensive care, and most have used smaller samples of trials than our evaluation. The few assessments that addressed larger numbers of trials than we did used a qualitative categorization of favorable efficacy rather than a comparison of detailed effect size estimates within the same topic and outcome. Evaluations not accounting for topic and outcome run the risk of confounding if industry trials are performed in topics and outcomes that are more likely to show larger effect sizes and favorable results. Across 25 assessments with 2923 trials, trials funded by industry were more likely to have favorable efficacy results [relative risk (RR) 1.27, 95% CI (1.17–1.37)] [6]. Thus, the results that we observed in the intensive care trials seem substantially different than for trials in other fields. Moreover, across 29 assessments with 4583 trials, trials funded by industry were more likely to have favorable conclusions (RR 1.34, 95% CI (1.19–1.51)] [6]. Definitions of “favorable” have varied across evaluations, but the average rate of favorable conclusions in previous assessments in other fields for industry-funded trials (86.6%) seems higher than what we observed for RCTs in intensive care. The average rate of favorable conclusions in trials without industry funding was 64.4%, which seems lower than what we observed in not-for-profit-funded intensive care research.

Overall, contrary to previous evaluations in other fields, in intensive care we found no evidence for more favorable results and conclusions in industry-funded trials; if anything, the opposite trend was observed. The difference may still be due to chance. Alternatively, it could be that for several interventions in intensive care where industry-funded trials yielded unfavorable results (e.g., corticosteroids, N-acetylcysteine, and levosimendan), treatments were inexpensive and thus there was no strong financial bias. Or, industry-funded trials may have been better done and more protected from bias. Nevertheless, it is of note that in the previous empirical evaluations, even when adjusting results for the quality of the study and its risk of bias, trials with industry funding remained associated with more positive conclusions, suggesting that whatever differences were not easily explained with standard risk of bias tools [11].

A recent study conducted in intensive care research found that more than half its trials were funded by non-profit organization, a quarter by industry, and the rest by mixed sources of funding across a total of 391 assessed RCTs [47]. The modestly higher rate of industry funding observed in that evaluation may be due to differences in eligibility criteria (e.g., sample size greater than 100, trials published in 1990–2012). The authors found that the evidence in intensive care is increasingly being shaped by academic investigators with a decline in the number of studies with industry funding over time, and an increase in trials with non-profit funding [47]. One potential reason for the lack of interest from industry could be the specific setting of intensive care research where patients are more at risk of dying and where the complex logistics might make it more difficult to conduct a clinical trial. One proposed solution is to follow the investigator-led research model [47], by which consortia of independent investigators could help improve intensive care research and develop new mechanisms of private–public collaborations to fund it. Developing an agenda of large-scale trials with relevant clinical outcomes, publicly transparent and prespecified protocols, and protection from sponsor bias may help make major progress in intensive care research.

A substantial proportion of RCTs in intensive care do not report any information on funding. Nine trials stated that they had received no funding and, given the logistics of running an RCT, it is difficult to envision an RCT in the intensive care setting that was done without any financial support, including overheads, but it is unlikely that these trials were industry-funded. A much larger number of RCTs simply make no comment on funding. The funding, if any, of these trials remains a black box. Perhaps these trials could also have been covertly funded by industry. Alternatively, these trials could also have been funded by non-profit organizations or may have had no specific support whatsoever. However, it has been shown that articles from clinical medicine journals compared with other fields are almost twice as likely to not include information on the funder and yet to have funding from industry [48]. There is a need to increase the enforcement of the reporting of funding source as required by the CONSORT statement [14] at the trial level but also at the systematic review level. Without such information it is difficult to apprehend the full extent of the industry involvement in clinical trials research and even to determine the needs in funding from public institutions to cover unmet needs.

Our overview has several limitations. First, we only considered trials already included in meta-analyses and this would exclude trials that have not been subjected to meta-analysis. Moreover, information on funding of RCTs is not commonly reported in journal-published meta-analyses, and despite our effort to scrutinize drug and biologic trials in their original publications, several other topics could not be assessed. Second, for consistency we only focused on binary outcomes for the ROR analysis. However, binary outcomes represent the majority of the evidence with only seven reviews excluded on this basis. Third, we did not assess the quality of the trials or compare the quality between with and without industry-funded trials. Evidence from other fields suggests that while in the past industry trials may have had quality deficits, more recent trials funded by industry do well or better in quality checklists than non-industry-funded trials [2, 49, 50]. Moreover, as we stated above, standard risk of bias tools do not seem to explain differences in favorable results and conclusions in trials with versus without industry funding [6]. Fourth, before 2015 we only covered the Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, because journal meta-analyses rarely report the funding source of the RCTs and old meta-analyses may also not be very up-to-date about the status of the evidence. Fifth, our assessment included relatively few trials on medical devices. Medical devices are evolving rapidly owing to the development of new technologies and are less regulated compared to drug interventions [51]. Whether industry-funded trials on devices might present more favorable outcomes requires further investigation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

METRICS is supported by a grant from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. The work of JPA Ioannidis is supported by an unrestricted gift from Sue and Bob O’Donnell. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study. PJ and IAC extracted data and all authors analyzed the data and interpreted the results. PJ wrote the first draft and all authors contributed to the writing of the paper and approved the final version

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Data

All the data collected for this study are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:454–465. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326:1167–1170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patsopoulos NA, Ioannidis JPA, Analatos AA. Origin and funding of the most frequently cited papers in medicine: database analysis. BMJ. 2006;332:1061–1064. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38768.420139.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bero L, Oostvogel F, Bacchetti P, Lee K. Factors associated with findings of published trials of drug-drug comparisons: why some statins appear more efficacious than others. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ioannidis JPA, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383:166–175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, et al. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:MR000033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.mr000033.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drain PK, Parker RA, Robine M, Holmes KK. Global migration of clinical research during the era of trial registration. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moses H, Matheson DHM, Cairns-Smith S, et al. The anatomy of medical research: US and international comparisons. JAMA. 2015;313:174–189. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamatakis E, Weiler R, Ioannidis JPA. Undue industry influences that distort healthcare research, strategy, expenditure and practice: a review. Eur J Clin Investig. 2013;43:469–475. doi: 10.1111/eci.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jørgensen AW, Hilden J, Gøtzsche PC. Cochrane reviews compared with industry supported meta-analyses and other meta-analyses of the same drugs: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;333:782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38973.444699.0B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yank V, Rennie D, Bero LA. Financial ties and concordance between results and conclusions in meta-analyses: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335:1202–1205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39376.447211.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lathyris DN, Patsopoulos NA, Salanti G, Ioannidis JPA. Industry sponsorship and selection of comparators in randomized clinical trials. Eur J Clin Investig. 2010;40:172–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lexchin J. Those who have the gold make the evidence: how the pharmaceutical industry biases the outcomes of clinical trials of medications. Sci Eng Ethics. 2012;18:247–261. doi: 10.1007/s11948-011-9265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:726–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakoum MB, Jouni N, Abou-Jaoude EA, et al. Characteristics of funding of clinical trials: cross-sectional survey and proposed guidance. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015997. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen HK, et al. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coopersmith CM, Wunsch H, Fink MP, et al. A comparison of critical care research funding and the financial burden of critical illness in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1072–1079. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823c8d03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitka M. NIH signals intent to boost funding of emergency care research and training. JAMA. 2012;308:1193–1194. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedrich JO, Adhikari NKJ, Beyene J. Inclusion of zero total event trials in meta-analyses maintains analytic consistency and incorporates all available data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ioannidis JPA, Patsopoulos NA, Rothstein HR. Reasons or excuses for avoiding meta-analysis in forest plots. BMJ. 2008;336:1413–1415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter J, Olkin I. Why add anything to nothing? The arcsine difference as a measure of treatment effect in meta-analysis with zero cells. Stat Med. 2009;28:721–738. doi: 10.1002/sim.3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siempos II, Ntaidou TK, Filippidis FT, Choi AMK. Effect of early versus late or no tracheostomy on mortality and pneumonia of critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:150–158. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang B, Chen R, Guo X, et al. Effects of levosimendan on mortality in patients with septic shock: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:100524–100532. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volbeda M, Wetterslev J, Gluud C, et al. Glucocorticosteroids for sepsis: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1220–1234. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3899-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osadnik CR, Tee VS, Carson-Chahhoud KV, et al. Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD004104. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004104.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillies D, Todd DA, Foster JP, Batuwitage BT. Heat and moisture exchangers versus heated humidifiers for mechanically ventilated adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD004711. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004711.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solé-Lleonart C, Rouby J-J, Blot S, et al. Nebulization of antiinfective agents in invasively mechanically ventilated adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:890–908. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellù R, de Waal KA, Zanini R. Opioids for neonates receiving mechanical ventilation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004212. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004212.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guay J, Ochroch EA. Intraoperative use of low volume ventilation to decrease postoperative mortality, mechanical ventilation, lengths of stay and lung injury in patients without acute lung injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd011151.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuriyama A, Umakoshi N, Fujinaga J, Takada T. Impact of closed versus open tracheal suctioning systems for mechanically ventilated adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:402–411. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sud S, Sud M, Friedrich JO, et al. High-frequency oscillatory ventilation versus conventional ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD004085. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004085.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Ding S, Li C, et al. Effects of N-acetylcysteine treatment in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:2863–2868. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Busani S, Damiani E, Cavazzuti I, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in septic shock: review of the mechanisms of action and meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016;82:559–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alarcon JD, Rubiano AM, Okonkwo DO, et al. Elevation of the head during intensive care management in people with severe traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD009986. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd009986.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradt J, Dileo C. Music interventions for mechanically ventilated patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd006902.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morag I, Ohlsson A. Cycled light in the intensive care unit for preterm and low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd006982.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose L, Adhikari NK, Leasa D, et al. Cough augmentation techniques for extubation or weaning critically ill patients from mechanical ventilation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:CD011833. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd011833.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu R, Lin S-Y, Zhao H-M. Albuterol in the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Emerg Med. 2015;6:165–171. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monro-Somerville T, Sim M, Ruddy J, et al. The effect of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy on mortality and intubation rate in acute respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e449–e456. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flacco ME, Manzoli L, Boccia S, et al. Head-to-head randomized trials are mostly industry sponsored and almost always favor the industry sponsor. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thorlund K, Imberger G, Johnston BC, et al. Evolution of heterogeneity (I2) estimates and their 95% confidence intervals in large meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan A-W, Altman DG. Epidemiology and reporting of randomised trials published in PubMed journals. Lancet. 2005;365:1159–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71879-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ioannidis JP, Caplan AL, Dal-Ré R. Outcome reporting bias in clinical trials: why monitoring matters. BMJ. 2017;356:j408. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tonelli AR, Zein J, Adams J, Ioannidis JPA. Effects of interventions on survival in acute respiratory distress syndrome: an umbrella review of 159 published randomized trials and 29 meta-analyses. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:769–787. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3272-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall JC, Kwong W, Kommaraju K, Burns KEA. Determinants of citation impact in large clinical trials in critical care: the role of investigator-led clinical trials groups. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:663–670. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iqbal SA, Wallach JD, Khoury MJ, et al. Reproducible research practices and transparency across the biomedical literature. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rios LP, Odueyungbo A, Moitri MO, et al. Quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials in general endocrinology literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3810–3816. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pengel LHM, Barcena L, Morris PJ. The quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials in solid organ transplantation. Transpl Int. 2009;22:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kesselheim AS, Rajan PV. Regulating incremental innovation in medical devices. BMJ. 2014;349:g5303. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.