Abstract

Severe asthma is a subtype of asthma that is difficult to treat and control. By conservative estimates, severe asthma affects approximately 5–10% of patients with asthma worldwide. Severe asthma impairs patients’ health-related quality of life, and patients are at risk of life-threatening asthma attacks. Severe asthma also accounts for the majority of health care expenditures associated with asthma. Guidelines recommend that patients with severe asthma be referred to a specialist respiratory team for correct diagnosis and expert management. This is particularly important to ensure that they have access to newly available biologic treatments. However, many patients with severe asthma can suffer multiple asthma attacks and wait several years before they are referred for specialist care. As global patient advocates, we believe it is essential to raise awareness and understanding for patients, caregivers, health care professionals, and the public about the substantial impact of severe asthma and to create opportunities for improving patient care. Patients should be empowered to live a life free of symptoms and the adverse effects of traditional medications (e.g., oral corticosteroids), reducing hospital visits and emergency care, the loss of school and work days, and the constraints placed on their daily lives. Here we provide a Patient Charter for severe asthma, consisting of six core principles, to mobilize national governments, health care providers, payer policymakers, lung health industry partners, and patients/caregivers to address the unmet need and burden in severe asthma and ultimately work together to deliver meaningful improvements in care.

Funding: AstraZeneca.

Keywords: Health care policy, Patient advocacy, Patient care, Respiratory, Severe asthma

Introduction

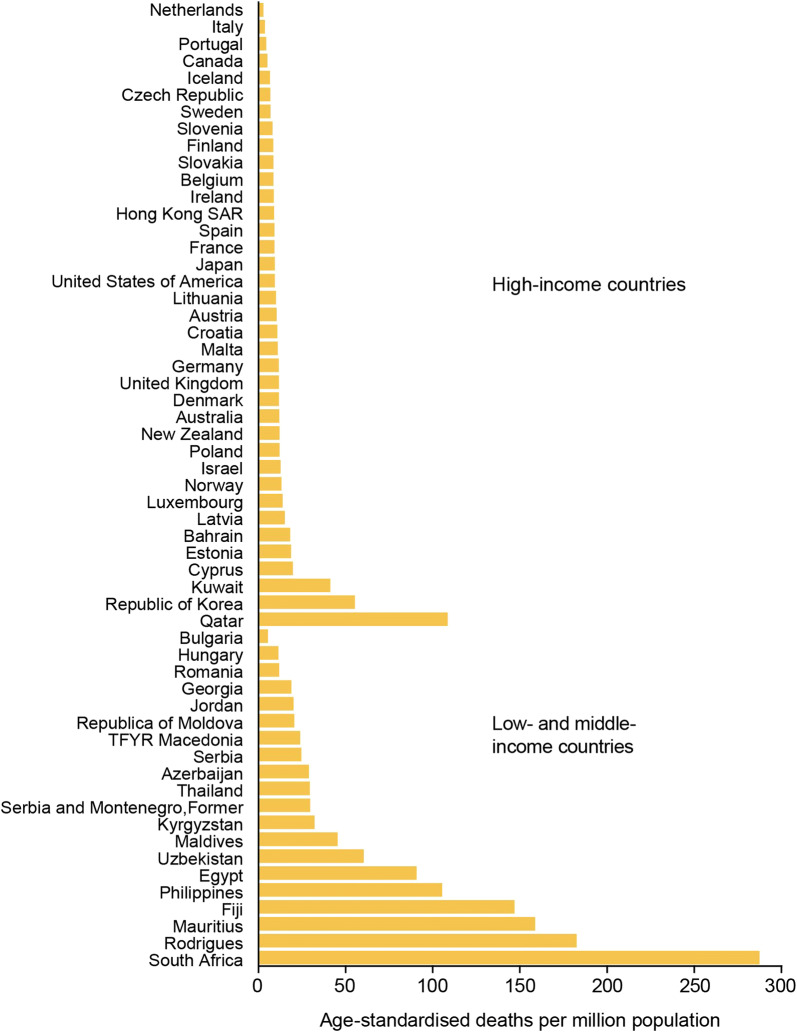

Worldwide, up to 334 million people are estimated to be living with asthma [1]. Patients with asthma experience respiratory symptoms, such as wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, cough, and airway obstruction, that can vary over time [2]. Overall, asthma is often regarded as a controllable condition, but asthma constitutes a significant public health problem across all countries, regardless of development level [3]. Asthma varies between individual patients in its underlying disease mechanisms, the type and intensity of symptoms, and treatment response [2]. Some subtypes, such as severe asthma, do not fully respond to established treatments. In 2010, 345,000 asthma-related deaths were reported worldwide (Fig. 1) [1, 4]. Many of these asthma-associated deaths potentially could have been prevented with improved patient management, more complete implementation of existing recommendations, and increased access to specialist care [5–7].

Fig. 1.

Age-standardized asthma mortality rates for asthma overall for all ages, 2001–2010 [1]. Average number of deaths and average population for each 5-year age group over the period 2001–2010, using all available data for each country (the number of available years over this period ranged from 1 to 10). Reproduced with kind permission from the Global Asthma Network from: Global Asthma Network. The Global Asthma Report 2014. http://www.globalasthmareport.org/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2014.pdf

Severe asthma is hard to control and affects 5–10% of patients with asthma [8]. This may be a conservative estimate. For many patients with severe asthma, symptoms do not improve with the usual standard of care [inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)], even when medicines are taken correctly and other potential causes of symptoms have been ruled out [8]. Therefore, traditional treatments are either less effective for these patients or must be taken in extremely high dosages, exposing patients to associated and substantial adverse effects. Patients with severe asthma also have more frequent life-threatening asthma attacks, which can have a devastating impact on people’s lives [9]. The struggle to breathe can be a day-to-day challenge that overshadows much of the sufferer’s daily activities, potentially resulting in hospital admissions, intensive care, and even death [9, 10].

In addition to the burden on the individual with severe asthma, the disease impacts on health systems and society [11]. The relatively small severe asthma patient population drives a significant percentage of health care cost, estimated in some countries to be 50% of all asthma-related costs [12]. In other health systems, the care required to treat a patient with severe asthma can be up to five times more expensive than the care required for mild asthma ($1579 vs. $298 US dollars, respectively) [11].

Guidelines written by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) in 2014 are recognized as the best clinical guidance for severe asthma diagnosis and treatment [8]. However, understanding of the biology and needs of patients with severe asthma is rapidly evolving, and new treatments (e.g., biologics) are being introduced [13]. Approaches to care must reflect these changes and the increasing treatment options available. In response to these changes, we, as representatives of the academic treating community, patient support groups, and professional organizations, have developed a Patient Charter for the care of patients with severe asthma with six principles for consideration (see Box 1 in Appendix). These principles set out to define what patients should expect for the management of their severe asthma and what should constitute a basic standard of care, in line with the latest science and best practice understanding from existing severe asthma care services.

Principle 1: I Deserve a Timely, Straightforward Referral When My Severe Asthma Cannot Be Managed in Primary Care

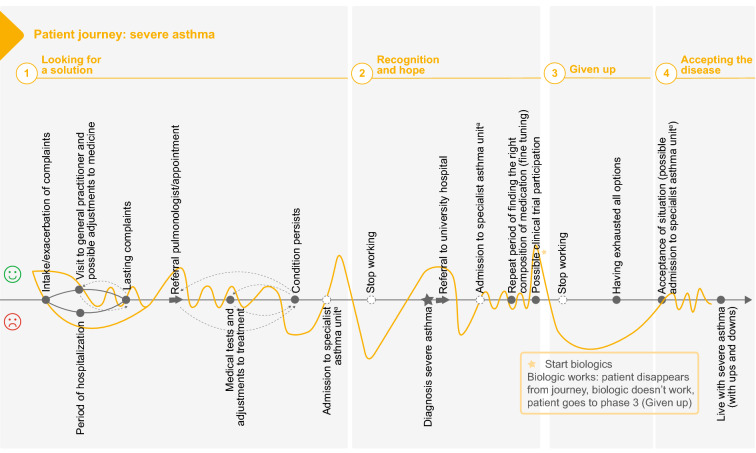

Internationally recognized guidelines for the management of asthma state that severe asthma is a complex condition that requires input from experts to confirm the diagnosis and for appropriate management [6, 8]. However, people with severe asthma often experience several asthma attacks (also known as exacerbations) and admission to emergency departments before they are referred for specialist care [6, 7]. Some patients spend up to 7 years experimenting with different treatments and suffering from associated debilitating treatment adverse effects before being referred to a respiratory specialist [6, 9, 14]. Four patient journey phases were identified from semistructured in-depth interviews with a small sample of patients from The Netherlands diagnosed with severe asthma: “looking for a solution,” “recognition and hope,” “given up,” and “accepting the disease” (Fig. 2) [15]. During this lengthy journey, severe asthma was reported to dominate patients’ lives, making it difficult for them to live the lives they imagined [15]. Shortening the patient journey is key to improving the health-related quality of life for patients with severe asthma. However, it appears that many health care professionals do not recognize severe asthma as a distinct form of asthma. They perhaps presume that people with regularly uncontrolled symptoms have poorly controlled mild/moderate asthma caused by poor treatment adherence.

Fig. 2.

Patient perspective on severe asthma: four phases of the patient journey [15]. Results based on semistructured in-depth interviews with patients (and their relatives) in their own homes that lasted ~ 2 h. All patients were diagnosed with severe asthma by a pulmonologist (six patients were diagnosed with severe allergic disease). No patients had a diagnosed comorbidity with symptoms similar to asthma. aAdmission to Heideheuvel/Davos. Reproduced with kind permission from Beautiful Lives, Hilversum, The Netherlands

Patients who present to their general practitioner with difficult-to-manage asthma should be adequately assessed using a structured methodology, such as the “SIMPLES” approach, before severe asthma is considered and the patient is referred to a severe asthma specialist clinic [16]. The “SIMPLES” approach, aligned with cooperation between primary and specialist care, can avoid inappropriate escalation of treatment, streamline clinical assessment and management, and optimize patient referrals [16]. Patients and health care professionals should also have access to a simple, understandable set of criteria for identifying severe asthma based on best practice guidance, such as the ATS/ERS and Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines [2, 8]. In general, patients experiencing any of the following should be referred to an expert respiratory physician: oral corticosteroid (OCS) use for > 3 months, more than two rounds of OCS treatment in the past 12 months, hospitalization for asthma in the past 12 months, or impaired lung function despite optimized standard therapy.

Education within the health care and patient communities on these referral criteria would facilitate rapid referral, and systems already in place in many health authorities could be used to automate this process. Studies have reported that patients under the care of an asthma specialist have a reduced risk of being hospitalized for an asthma attack compared with those being managed by a nonspecialist [6].

Principle 2: I Deserve a Timely, Formal Diagnosis of My Severe Asthma By an Expert Team

An accurate diagnosis is the foundation of effective asthma care [2, 6]. An initial diagnosis of asthma usually occurs in primary care, based on objective testing over a period of time. However, a formal diagnosis of severe asthma requires a more complex assessment following referral to a respiratory specialist [6]. Part of the reason why a diagnosis of severe asthma is complex is the lack of a clear and consistently used definition of severe asthma. Definitions of severe asthma have historically been based on the degree of symptoms, but newer guidance considers the treatment required to attain control. According to international guidelines, asthma is considered severe if, despite the elimination of modifiable factors (e.g., poor inhaler technique/adherence, persistent environmental exposure to disease triggers), it requires high-dosage ICS plus a second controller with or without oral OCS to prevent it from becoming uncontrolled or if it remains uncontrolled despite this treatment [2].

It is recommended that a diagnosis of severe asthma should be completed by a specialist multidisciplinary team (MDT) with access to the appropriate resources [6, 7, 17]. However, prior to referral, patients presenting with uncontrolled asthma in primary care initially should be assessed to ensure that their symptoms do not remain uncontrolled because of factors other than severe disease [2]. It should first be determined if patients are taking their prescribed medication properly, with good inhaler technique. The presence of uncontrolled comorbid conditions that may reduce the effectiveness of asthma medications (e.g., chronic sinusitis, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease) should also be investigated [2]. Measures to improve the accuracy of diagnosis for patients with mild and moderate asthma and persistent symptoms caused by poor medication adherence or triggers other than asthma would also help to ensure appropriate use of specialist care [6].

In other conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, there are clear referral pathways and set waiting time targets to ensure rapid diagnosis [18, 19]. Establishing similar targets and clear referral pathways for patients with asthma would help patients receive an accurate, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Principle 3: I Deserve Support to Understand My Type of Severe Asthma

Although severe asthma is complex [20], scientific understanding of the disease is progressing rapidly. The existence of disease subtypes and the complexity of the causes of severe asthma, including genetic, allergic, and environmental factors, contribute to the requirement for tailored specialist care [9]. Different subtypes of the disease (known as phenotypes and endotypes) have been characterized based on patients’ underlying disease mechanisms, triggers, and responses to treatment (Table 1). Some biologic markers (substances that can identify disease processes) have also been identified that can accurately characterize the underlying causes of a patient’s disease and how it should be managed [9, 21]. Thus, the treatment of asthma, and particularly severe asthma, has moved away from the established trial-and-error, step-up method of treatment and toward a more personalized approach [22]. This follows the trend toward personalized medicine in other diseases. Patients with cancer, for example, increasingly receive treatment with therapies targeted at the characteristics of their cancer cells, as opposed to traditional chemotherapy, which uses drugs that are toxic to many cells besides cancer cells [23].

Table 1.

Summary of recognized asthma subtypes (endotypes and phenotypes) based on disease characteristics, treatment response, and disease mechanisms

| Description | Markers associated with the disease | Disease onset | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergic asthma | Blood IgE [36] | Early/childhood [37] | Genetic tendency to develop allergies is associated with all asthma types, but prevalence is increased in those with early onset [37] |

| Eosinophilic asthma | Eosinophils (IL-5) [38] | Late/adult [39] |

Blood/sputum eosinophil count is a predictive biomarker for increased severity of asthma attacks [40] Targeting eosinophils may improve asthma control [39] |

| Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease | Eosinophils, also IgE | Late/adult |

Often severe and exhibits sinusitis and nasal polyposis Presents as an NSAID allergy May be genetic [41] |

| Neutrophilic asthma | Neutrophils (IL-8) | Late/adult [42] |

Neutrophils in the airways are associated with reduced lung function and thicker airway walls [42] Typically experienced by patients treated with corticosteroids, limited management options [42] |

| Obesity-associated asthma | Lack of biomarkers [42] | Late/adult |

Poor response to corticosteroid therapy [43] Weight loss may improve symptoms [44] |

| Exercise-induced asthma | Cytokines, leukotrienes | Early |

Presents intermittently with strenuous exercise More common in athletes with a genetic tendency to develop allergies [41] |

Ig immunoglobulin, IL interleukin, NSAID nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug

The published European Charter of Patients’ Rights states, “Each individual has the right to freely choose from among different treatment procedures and providers on the basis of adequate information” [24]. Patients should receive relevant information from his or her health care professional in a simple and clear format to better understand the treatment options available and the consequences of different management approaches. Such provision represents a definite unmet need for patients with severe asthma [22].

Principle 4: I Deserve Care that Reduces the Impact of Severe Asthma on My Daily Life and Improves My Overall Quality of Care

Severe asthma differs from mild and moderate asthma, in part because the patient experience is much worse. Symptoms can affect relationships, careers, parenting, and social lives, and sometimes patients’ abilities to undertake the most basic daily tasks [25]. Patients with severe asthma also have more frequent life-threatening asthma attacks, resulting in hospital admission and potentially death [9]. Furthermore, the adverse effects associated with treatments to manage and prevent such asthma attacks (including OCS, on which patients can become dependent) can also represent a significant burden for people with severe asthma [26].

The goal of asthma management is to achieve disease control. The definition of asthma control is based on symptoms, lung function, sleep disturbance, limitations of daily activity, use of rescue medication, and the overall assessment of patients and physicians [27]. Assessment of asthma control is used to inform changes made to a patient’s asthma management plan and for prompt referral to a specialist for diagnosis of severe asthma [27]. The benefits of good asthma control include reduced health care resource utilization, fewer missed work/school days, and a lesser risk of asthma attacks [28].

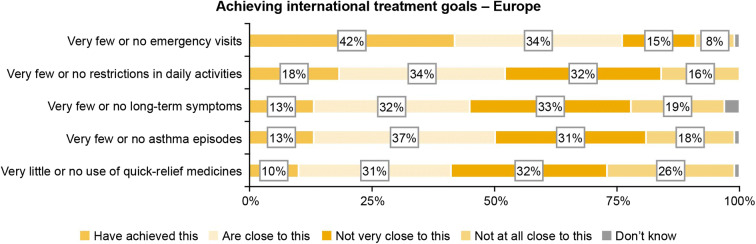

An international study of nonspecialist physicians treating patients with asthma reported that only 10% used validated patient questionnaires to determine if their patients’ asthma was controlled and just 37% of patients had a written asthma action plan [29]. It has been reported that many patients with severe asthma underestimate the severity of their condition and overestimate how well it is controlled [30]. In addition, as many as 70% of patients have become accustomed to compromising their daily activities to accommodate living with severe asthma [10]. GINA guidelines define goals for asthma treatment and expected health outcomes. However, a European study reported that a low percentage of patients with severe asthma are achieving these goals (Fig. 3) [10], highlighting the unmet need for improved treatment and management of patients with severe asthma.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients with severe asthma achieving international treatment goals [10]. Reproduced with kind permission from the European Federation of Allergy and Airways Diseases Patients Association (EFA) from: European Federation of Allergy and Airways Diseases Patients Association (EFA). A European patient perspective on severe asthma: Fighting for breath http://www.efanet.org/images/2012/07/Fighting_For_Breath1.pdf

There is a need to educate patients living with severe asthma to recognize persistent symptoms and know to seek expert treatment to potentially achieve a better health-related quality of life. Frequent patient education on correct inhaler technique is also important to ensure the optimal effect of currently prescribed medications. There should be shared decision-making between patients and their clinicians to ensure that care focuses on limiting the impact of symptoms and the adverse effects of treatment on physical, mental, and emotional health. Each person will be different, so care should be personalized to address what matters most to each individual [22].

Principle 5: I Deserve Not to Be Reliant on Oral Corticosteroids

Compared with patients with milder controlled disease, patients with severe asthma also experience adverse effects from treatments that are used to manage asthma attacks (e.g., OCS). If these treatments are used long term, the resulting adverse effects may include weight gain, diabetes, osteoporosis, glaucoma, anxiety, cardiovascular disease, and impaired immunity [17]. These can be debilitating, with a significant impact on both other conditions that patients may have and overall health-related quality of life [9]. Adverse effects also have a significant impact on the utilization of additional health care services [31, 32]. Asthma UK reports that patients “loathe” these treatments and that the substantial adverse effects are a significant reason they do not comply with their prescribed medications, which puts them at risk of experiencing a future asthma attack [9, 14]. Now that new, targeted treatment options based on increased understanding of the biology of the underlying disease are available, there is a growing call for severe asthma care to be less reliant on the long-term use of OCS to prevent asthma attacks [9].

Principle 6: I Deserve to Access Consistent Quality Care, Regardless of Where I Live or Where I Choose to Access It

Severe asthma requires input from a specialist team to confirm a diagnosis and determine the best treatment/management approach for individual patients [6, 8]. However, management practices and patients’ experiences of asthma care exhibit geographic variation, and there is also inconsistency within countries in how patients are managed [6]. A study in seven European countries reported that management and control of asthma were below the standard defined in the GINA guidelines, with most adults (49.5–73.0%) and many children (38.4–70.6%) only having a follow-up visit for their asthma when they experienced an asthma attack [31, 33]. Furthermore, in our experience, it can take patients an astounding 10–20 years to be referred to a respiratory specialist in many countries.

New care models should be considered for the delivery of severe asthma services to improve efficiency and ensure that patients have access to consistent quality care. Treatment of conditions such as diabetes and stroke has been transformed using networks and technology to deliver efficient but effective specialized care [34]. People with severe asthma should receive a personalized approach throughout their treatment journey based on their own individual needs [22].

Discussion

Severe asthma places a significant burden on health systems and the lives of patients. Despite existing treatment guidelines, the management of patients with severe asthma in practice all too often fails to sufficiently achieve outlined goals. There is, therefore, a need to urgently review the current care provided for patients with asthma and raise the expectations regarding their diagnosis and treatment. Improvements in the quality of care for patients with asthma falls behind that achieved for other diseases. For example, a patient experiencing a heart attack would not be released from the hospital after an initial attack had been controlled without a plan for follow up and treatment to prevent future attacks. Yet this is the experience of many patients hospitalized for an asthma attack, even though these patients are very likely to experience another attack that could be potentially fatal.

During the past 20 years, the introduction of biologics for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, along with improved care from a MDT, has transformed the experience of patients with this disease. Early diagnosis and effective treatment have resulted in a reduction in the number of surgeries and hospitalizations required for the management of rheumatic disease [35]. Steroid therapy is no longer overused. The same revolution is occurring in the treatment of patients with severe asthma, with new biologic treatments becoming available that have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing future asthma attacks for patients with defined subtypes of severe asthma [13]. However, ensuring that patients with severe asthma who may potentially benefit from these new treatments are identified and seen by specialists is fundamental to achieving these improvements. Early diagnosis is particularly important to facilitate the prescribing of these new biologics or to enable patients to enroll in clinical studies of other novel therapies.

To implement these principles, we recommend the following. Asthma patients should request written asthma treatment action plans from physicians, with specific goals detailed, as a mandatory part of the care they receive. They should also request that both their physicians and pharmacists provide or make available training of inhaler technique to them before they fill new prescriptions. This “double check” can help avoid errors. In addition, patient organizations should reinforce the need for written action plans and frequent checks of inhaler technique. Many patient organizations have programs to detail what should be in a written action plan and why is it useful and often provide instructional recordings demonstrating correct inhaler techniques. Patient organization representatives should screen meeting participants as they demonstrate their inhaler techniques and review written action plans to verify they understand them correctly.

The principles we have set out in the Charter to Improve Patient Care in Severe Asthma demonstrate the core elements of quality care that patients with severe asthma should expect to receive. They are based on the latest understanding of the disease and how care should be structured. These principles should be used to benchmark current service provision. We urge policymakers, those responsible for the delivery of severe asthma care, and advocates for better care to use the principles and action plan we have set out here to build consensus on what severe asthma care should look like in their health system, place people with asthma at the center of care, identify the current gaps and areas for improvement, and implement measures to improve the quality of care and outcomes for people with severe asthma with a view to promoting a life with minimal symptoms.

Acknowledgements

The Patient Charter was initiated by AstraZeneca to inform a discussion about what quality care should look like in the provision of severe asthma services. These principles were debated and refined during a discussion held on 8 September 2017 in Milan, Italy, organized and funded by AstraZeneca. Twelve academic, patient organization, and professional group experts discussed the value of establishing a Patient Charter as a potential starting point for discussions on how to improve severe asthma care.

Funding

Funding for this study, the article processing charges, and the open access charge was provided by AstraZeneca.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. The authors thank Ümit Kaynak and Nella van Rhijn-van Gemert of Beautiful Lives, a human insights research firm in Hilversum, The Netherlands, for providing the sample severe asthma patient journey described in this manuscript and illustrated in Fig. 2. This was funded by AstraZeneca, The Netherlands.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Writing and editing assistance, including preparation of a draft manuscript under the direction and guidance of the authors, incorporating author feedback, and manuscript submission, was provided by Debra Scates, PhD, of JK Associates, Inc., and Michael A. Nissen, ELS, of AstraZeneca. This support and charges related to the publication of this article were funded by AstraZeneca.

Disclosures

Andrew Menzies-Gow has consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca and Vectura; was an advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis, and Teva; received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Teva, and Vectura; has received clinical funding from AstraZeneca; has participated in research that his institution has been remunerated from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Hoffman La Roche; and has attended international conferences sponsored by AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. Jaime Correia de Sousa has been an advisory board member with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis; has received payment for lectures from Boehringer Ingelheim and Mundipharma; and has received payment for development of educational presentations from Boehringer Ingelheim. John W. Upham has received consultancy and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, and Novartis. Antje-Henriette Fink-Wagner has consulted for AstraZeneca, Novartis and Teva on severe asthma. G-Walter Canonica has been an advisory board member with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Mundipharma, Menarini, Chiesi, ALK, Stallergenes, Hal Allergy, Sanofi Regeneron; has received payment for lectures from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Menarini, Chiesi, Stallergenes, Hal Allergy; and has participated in research for his institution supported by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Mundipharma, Menarini, Chiesi. Sanofi Regeneron. Tonya A. Winders has consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca for the PRECISION program.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Appendix

Box 1: Charter to improve patient care in severe asthma principles

|

Principle 1: I deserve a timely, straightforward referral when my severe asthma cannot be managed in primary care. Principle 2: I deserve a timely, formal diagnosis of my severe asthma by an expert team. Principle 3: I deserve support to understand my type of severe asthma. Principle 4: I deserve care that reduces the impact of severe asthma on my daily life and improves my overall quality of care. Principle 5: I deserve not to be reliant on oral corticosteroids. Principle 6: I deserve to access consistent quality care, regardless of where I live or where I choose to access it. |

Footnotes

Enhanced digital content

To view enhanced digital content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.6979331.

References

- 1.Global Asthma Network. The Global Asthma Report. 2014. http://www.globalasthmareport.org/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2014.pdf. Accessed June 2018.

- 2.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2018. http://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention. Accessed June 2018.

- 3.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2018. http://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention. Accessed June 2018.

- 4.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Amato G, Vitale C, Molino A, Stanziola A, Sanduzzi A, Vatrella A, et al. Asthma-related deaths. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2016;11:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price D, Bjermer L, Bergin DA, Martinez R. Asthma referrals: a key component of asthma management that needs to be addressed. J Asthma Allergy. 2017;10:209–23. 10.2147/JAA.S134300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills. The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD). 2014. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/868/download?token=JQzyNWUs. Accessed June 2018.

- 8.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343–73. 10.1183/09031936.00202013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asthma UK. Severe asthma: the unmet need and the global challenge. 2017. https://www.asthma.org.uk/get-involved/campaigns/publications/severe-asthma-report. Accessed June 2018.

- 10.European Federation of Allergy and Airways Diseases Patients Association (EFA). A European patient perspective on severe asthma: Fighting for breath 2012. http://www.efanet.org/images/2012/07/Fighting_For_Breath1.pdf. Accessed June 2018.

- 11.Bahadori K, Doyle-Waters MM, Marra C, Lynd L, Alasaly K, Swiston J, et al. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:24. 10.1186/1471-2466-9-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Allergy Organisation. The management of severe asthma: economic analysis of the cost of treatments for severe asthma. 2005. http://www.worldallergy.org/educational_programs/world_allergy_forum/anaheim2005/blaiss.php. Accessed June 2018.

- 13.Quirce S, Phillips-Angles E, Dominguez-Ortega J, Barranco P. Biologics in the treatment of severe asthma. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2017;45(Suppl 1):45–9. 10.1016/j.aller.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asthma Society Canada. Severe asthma: the Canadian patient journey. 2014. https://www.asthma.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/SAstudy.pdf. Accessed June 2018.

- 15.Kaynak U, van Rhijn PC (Beautiful Lives). Patient perspective on severe asthma; insights into the patient journey. The Lung Week. April 9–12, 2018, Ermelo, The Netherlands. Abstract available at: https://www.weekvandelongen.nl/nl/abstracts. Accessed June 2018.

- 16.Ryan D, Murphy A, Stallberg B, Baxter N, Heaney LG. ‘SIMPLES’: a structured primary care approach to adults with difficult asthma. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(3):365–73. 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, Krishnamoorthy P, Mandelcorn ED, Leigh R, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2013;9(1):30. 10.1186/1710-1492-9-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NHS England. Delivering cancer wait times. 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/delivering-cancer-wait-times.pdf. Accessed June 2018.

- 19.National Institute for Health and Care Excellance (NICE). Management of suspected rheumatoid arthritis. 2013. https://cks.nice.org.uk/rheumatoid-arthritis#!scenario. Accessed June 2018.

- 20.Kane B, Cramb S, Hudson V, Fleming L, Murray C, Blakey JD. Specialised commissioning for severe asthma: oxymoron or opportunity? Thorax. 2016;71(2):196. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore WC, Peters SP. Severe asthma: an overview. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(3):487–94. 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canonica GW, Ferrando M, Baiardini I, Puggioni F, Racca F, Passalacqua G, et al. Asthma: personalized and precision medicine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;18(1):51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu SM, Bilen MA, Tannir NM. Personalised cancer care: promises and challenges of targeted therapy. J R Soc Med. 2016;109(3):98–105. 10.1177/0141076816631154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Active Citizenship Network. European Charter of Patient Rights. 2002. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_overview/co_operation/mobility/docs/health_services_co108_en.pdf. Accessed June 2018.

- 25.Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, HMRI, Asthma Australia. A qualitative study of the lived experience of Australians with severe asthma, Executive Summary and Final Report. 2016. https://toolkit.severeasthma.org.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/Living-with-Severe-Asthma-Executive-Summary-FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 2018.

- 26.Hyland ME, Whalley B, Jones RC, Masoli M. A qualitative study of the impact of severe asthma and its treatment showing that treatment burden is neglected in existing asthma assessment scales. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(3):631–9. 10.1007/s11136-014-0801-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li JT, Oppenheimer J, Bernstein IL, Nicklas RA, Khan DA, Blessing-Moore J, et al. Attaining optimal asthma control: a practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(5):S3–11. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Byrne PM, Pedersen S, Schatz M, Thoren A, Ekholm E, Carlsson LG, et al. The poorly explored impact of uncontrolled asthma. Chest. 2013;143(2):511–23. 10.1378/chest.12-0412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman KR, Hinds D, Piazza P, Raherison C, Gibbs M, Greulich T, et al. Physician perspectives on the burden and management of asthma in six countries: the Global Asthma Physician Survey (GAPS). BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):153. 10.1186/s12890-017-0492-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lurie A, Marsala C, Hartley S, Bouchon-Meunier B, Dusser D. Patients’ perception of asthma severity. Respir Med. 2007;101(10):2145–52. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manson SC, Brown RE, Cerulli A, Vidaurre CF. The cumulative burden of oral corticosteroid side effects and the economic implications of steroid use. Respir Med. 2009;103(7):975–94. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lefebvre P, Duh MS, Lafeuille MH, Gozalo L, Desai U, Robitaille MN, et al. Acute and chronic systemic corticosteroid-related complications in patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(6):1488–95. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vermeire PA, Rabe KF, Soriano JB, Maier WC. Asthma control and differences in management practices across seven European countries. Respir Med. 2002;96(3):142–9. 10.1053/rmed.2001.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liddell A, Adshead S, Burgess E (The Kings Fund). Technology in the NHS: Transforming the patient’s experience of care. Report no: 978 1 8571 75745. 2008. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Technology-in-the-NHS-Transforming-patients-experience-of-care-Liddell-Adshead-and-Burgess-Kings-Fund-October-2008_0.pdf. Accessed June 2018.

- 35.Mallory GW, Halasz SR, Clarke MJ. Advances in the treatment of cervical rheumatoid: less surgery and less morbidity. World J Orthop. 2014;5(3):292–303. 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim HY, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. The many paths to asthma: phenotype shaped by innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(7):577–84. 10.1038/ni.1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore WC, Fitzpatrick AM, Li X, Hastie AT, Li H, Meyers DA, et al. Clinical heterogeneity in the severe asthma research program. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(Suppl):S118–24. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201309-307AW [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coumou H, Bel EH. Improving the diagnosis of eosinophilic asthma. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10(10):1093–103. 10.1080/17476348.2017.1236688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Groot JC, Ten Brinke A, Bel EH. Management of the patient with eosinophilic asthma: a new era begins. ERJ Open Res. 2015;1(1):24. 10.1183/23120541.00024-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Louis R, Lau LCK, Bron AO, Roldaan AC, Radermecker M, Djukanovic R. The relationship between airways inflammation and asthma severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):9–16. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9802048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desai M, Oppenheimer J. Elucidating asthma phenotypes and endotypes: progress towards personalized medicine. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116(5):394–401. 10.1016/j.anai.2015.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wenzel SE. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat Med. 2012;18:716. 10.1038/nm.2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boulet LP, Franssen E. Influence of obesity on response to fluticasone with or without salmeterol in moderate asthma. Respir Med. 2007;101(11):2240–7. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dixon AE, Pratley RE, Forgione PM, Kaminsky DA, Whittaker-Leclair LA, Griffes LA, et al. Effects of obesity and bariatric surgery on airway hyperresponsiveness, asthma control, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3):508–15. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.