Abstract

Introduction

The long-term safety of dimethyl fumarate (DMF) in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) has been studied in mainly Caucasian patients. The present interim analysis aimed to evaluate the 72-week safety of DMF in Japanese patients with RRMS.

Methods

Safety data of Japanese subjects enrolled in the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled APEX study (Part I) and its following open-label extension (Part II) were analysed at 72 weeks from the beginning of Part I. In Part I, subjects were randomised to DMF treatment or matching placebo while all subjects received DMF treatment during Part II. Adverse events (AEs) reported throughout the study period were recorded.

Results

Overall, 109 Japanese subjects completed 72 weeks of treatment. The incidence of AEs and serious AEs was 95% and 19%, respectively, in the DMF group compared with 84% and 18%, respectively, in the placebo group at 24 weeks. Common AEs (at least 5%) reported with treatment included nasopharyngitis, flushing, hot flush, gastrointestinal events, pruritus, rash, headache, increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). AEs led to discontinuation of DMF in 5% of patients and included MS relapse, flushing, abdominal pain, liver disorder and increased ALT/AST. After an initial decrease from baseline of 17% in the DMF group at week 24, the mean lymphocyte counts stabilised and were maintained until week 72. No opportunistic/serious infections nor malignancies were reported with DMF treatment. The incidences of AEs, serious AEs, and discontinuation due to AEs were similar between the DMF and the placebo groups.

Conclusion

The 72-week safety profile of DMF in Japanese patients with RRMS was consistent with previous studies that enrolled mostly Caucasian patients, with a lower incidence of flushing and related symptoms and a lower reduction in the lymphocyte count compared with previous reports.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01838668.

Funding

Biogen Japan Ltd.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-018-0788-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: APEX, Dimethyl fumarate, Japanese, Phase 3, Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, Safety

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system [1] and, with an estimated 2.3 million people affected, it is one of the most common neurological disorders worldwide [2].

In MS, autoimmune lymphocytic infiltration of the brain and spinal cord causes demyelination and damages the axons. Early in the course of the disease, these alterations are reversible and manifest as episodes of neurological symptoms (relapses), followed by recovery [1]. Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) accounts for approximately 85% of MS cases at diagnosis [2]. During the latter stages of the disease, widespread microglial activation and oxidative stress lead to extensive neurodegeneration, the extent of recovery is reduced and patients develop secondary progressive MS [2]. Therefore, the objectives of MS therapy include reducing the frequency of relapses and delaying disease progression. The pathophysiology of MS in Caucasian and Asian patients is similar; however, the prevalence and disease activity of primary progressive MS and RRMS are lower in Japan than in Western countries. Furthermore, differences in genetic and environmental factors may have an impact on the efficacy and safety of MS therapeutics [3, 4].

Dimethyl fumarate (DMF) is an oral disease-modifying drug whose mechanism of action includes anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory and neuroprotective/cytoprotective effects [5, 6]. DMF was approved for first-line treatment of relapsing forms of MS in the USA in 2013 and for RRMS in the European Union in 2014 [7]. In Japan, DMF received marketing approval in December 2016 for the prevention of relapses and delaying the progression of disability in patients with MS [7].

In previous phase 3 clinical studies, DMF significantly reduced relapse rates and improved measures of disease progression, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters, such as the number of gadolinium-enhancing (Gd+) and T2-weighted lesions [8–10]. In addition, DMF demonstrated a favourable safety profile and the incidence of adverse events (AEs) was similar to that observed with placebo (PBO) [8–10]. AEs that were most consistently associated with DMF include flushing and gastrointestinal events [8–10].

To date, there are few reports addressing the safety of DMF in Japanese patients with RRMS; in particular, safety data in patients who have been treated for more than 1 year is scarce. APEX was a phase 3 study conducted in patients with RRMS from East Asia (including Japan) and Eastern Europe to evaluate the efficacy and safety of DMF. APEX consisted of two parts: a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, PBO-controlled main study (Part I) and an open-label extension with a follow-up duration of up to 4.5 years (Part II). The initial efficacy analyses of the Japanese patients in Part I of APEX had shown that DMF improved radiological signs and clinical symptoms of MS [11], and these improvements were further confirmed by a subsequent efficacy analysis of the Japanese patients enrolled in Part II of the study [12]. Both of these findings were consistent with those observed in Caucasian patients receiving DMF. This interim report presents safety data collected from the main study baseline up to 72 weeks of treatment in Japanese patients with RRMS enrolled in the trial.

Methods

The APEX study was conducted at 54 sites located in Japan, South Korea, the Czech Republic and Poland. Only Japanese subjects were included in the present interim analysis. Part I began in March 2013 and was competed in April 2016, while Part II began in September 2013 and the cut-off date for this interim analysis was 29 April 2016.

Subjects aged 18–55 years who were diagnosed with RRMS according to the revised McDonald criteria [13], had an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 0.0–5.0 and experienced at least one relapse during the 12 months prior to randomisation or had a Gd+ lesion of the brain on an MRI performed within 6 weeks prior to randomisation were included in Part I. Diagnosis of primary progressive, secondary progressive or progressive relapsing MS, as defined by Lublin and Reingold [14], and diagnosis or history of neuromyelitis optica constituted the main exclusion criteria.

In Part I, subjects were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio to receive DMF 240 mg or matching PBO twice daily over the course of 24 weeks (Fig. S1). Subjects were instructed to take the study treatment orally with food by swallowing it without chewing. Subjects who completed Part I, including those who prematurely discontinued study treatment, but completed all scheduled visits, were eligible to proceed to Part II. Subjects who discontinued Part I because of AEs or for any other reason, except protocol-defined relapse and progression of disability, were excluded. During Part II, all subjects received open-label DMF 240 mg twice daily (Fig. S1).

Safety assessments included collection of AEs, physical and neurological examinations, vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), haematology, blood chemistry, lipid profile and urinalysis. In Part I (weeks 0–24), these assessments were carried out every 4 weeks, except physical and neurological examination and 12-lead ECG, which were carried out every 12 weeks. In Part II (weeks 24–72), safety assessments were carried out every 4 weeks until week 48, except physical examination and haematology, which were carried out every 12 weeks. After that, all assessments were conducted every 12 weeks until week 72 (interim analysis data cut-off). AEs were classified according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 13.1. Lymphocyte counts were categorised using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.0 (Grade 1: < lower limit of normal [LLN, 0.91 × 109 cells/L] and > 0.8 × 109 cells/L; Grade 2: < 0.8 × 109 cells/L and > 0.5 × 109 cells/L; Grade 3: < 0.5 × 109 cells/L and > 0.2 × 109 cells/L; Grade 4: < 0.2 × 109 cells/L).

All subjects who received at least one dose of study treatment were included in the safety analysis. Safety endpoints included the incidence of AEs, serious AEs (SAEs) and changes in laboratory parameters. AEs of special interest included flushing and related symptoms, gastrointestinal events, infections (including potential opportunistic infections), cardiovascular disorders, hepatic and renal disorders, as well as malignancies.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of participating institutions. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with local and international guidelines and regulations. All patients provided written informed consent before any evaluations or procedures were performed.

Results

At the beginning of the study, 115 Japanese patients were randomised to receive DMF 240 mg (n = 56) or matching PBO (n = 58) twice daily, and one subject refused treatment before the first dose was administered (Fig. S2). Baseline characteristics of Japanese subjects were well balanced between treatment groups at the beginning of both Part I and Part II (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Part I | Part II | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBO (n = 58) | DMF (n = 56) | PBO/DMF (n = 53) | DMF/DMF (n = 53) | |

| Age (years) | 36.4 ± 7.24 | 38.4 ± 8.16 | 36.1 ± 7.3 | 38.3 ± 8.2 |

| Female, n (%) | 46 (79) | 44 (79) | 42 (79) | 41 (77) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.5 ± 3.6 | 22.1 ± 3.5 | 21.6 ± 3.7 | 22.2 ± 3.6 |

| Time since first MS symptoms (years) | 7.1 ± 6.4 | 8.1 ± 5.9 | – | – |

| Prior therapy for MS, n | ||||

| Yes | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 |

| No | 27 | 25 | 22 | 23 |

| Relapses in previous 12 months | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | – | – |

| Relapses in previous 3 years | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 2.7 ± 1.9 | – | – |

| Time since last relapse (months) | 7.5 ± 8.4 | 6.0 ± 6.0 | – | – |

| EDSS score | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 1.4 |

| Number of Gd+ lesions | 1.6 ± 3.3 | 1.3 ± 2.6 | 0.7 ± 1.2a | 0.2 ± 0.6b |

| Volume of T2 hyperintense lesions (cm3) | 8.1 ± 8.9 | 5.7 ± 7.3 | 8.3 ± 10.1a | 5.8 ± 7.6b |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, unless specified otherwise

BMI body mass index, DMF dimethyl fumarate, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, Gd+ gadolinium-enhancing, MS multiple sclerosis, PBO placebo

an = 43

bn = 47

During Part I, three subjects (5%; due to liver disorder: n = 1; consent withdrawn: n = 1; confirmed pregnancy: n = 1) in the DMF group and five subjects (9%; due to liver function test abnormal: n = 1; relapse of MS: n = 1; consent withdrawn: n = 3) in the placebo group discontinued treatment prematurely; all remaining subjects entered Part II (DMF/DMF: n = 53; PBO/DMF: n = 53). During Part II, five subjects (9%; due to relapse of MS: n = 1; consent withdrawn: n = 3; stop taking DMF by subject: n = 1) in the DMF/DMF group and 11 subjects (21%; due to abdominal pain: n = 1; ALT increased and AST increased: n = 1; consent withdrawn: n = 6; confirmed pregnancies: n = 3) in the PBO/DMF group discontinued treatment prematurely. Reasons for treatment discontinuation are shown in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. At week 72 (interim analysis data cut-off), 48 subjects (91%) in the DMF/DMF group and 42 subjects (79%) in the PBO/DMF group continued to receive study treatment.

Part I

AEs and SAEs

During Part I, at least one AE was reported by 95% of subjects (n = 53) in the DMF group and 84% of subjects (n = 49) in the PBO group (Table 2). AEs related to study treatment were more common in subjects who received DMF (n = 36; 64%) than in those who received PBO (n = 16; 28%). The proportions of subjects who experienced SAEs were similar between the two groups (DMF: n = 10, 18%; PBO: n = 11, 19%; Table 3). Relapses of MS were more common in the PBO group (47%) than the DMF group (29%).

Table 2.

Adverse events that occurred in at least 5% of study subjects

| AE | Part I | Part II | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBO (n = 58) | DMF (n = 56) | PBO/DMF (n = 53) | DMF/DMF (n = 53) | |

| Any | 49 (84) | 53 (95) | 48 (91) | 48 (91) |

| Pharyngitis | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 22 (38) | 21 (38) | 26 (49) | 24 (45) |

| Sinusitis | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (6) |

| Relapse of MS | 27 (47) | 16 (29) | 12 (23) | 24 (45) |

| Flushinga | 2 (3) | 8 (14) | 10 (19) | 0 |

| Hot flusha | 1 (2) | 6 (11) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) |

| Diarrhoeaa | 5 (9) | 8 (14) | 5 (9) | 4 (8) |

| Nauseaa | 4 (7) | 6 (11) | 6 (11) | 2 (4) |

| Vomitinga | 0 | 3 (5) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) |

| Rasha | 0 | 3 (5) | 2 (4) | 7 (13) |

| Pruritusa | 2 (3) | 6 (11) | 5 (9) | 5 (9) |

| ALT increaseda | 2 (3) | 6 (11) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) |

| AST increaseda | 1 (2) | 4 (7) | 4 (8) | 1 (2) |

| Abdominal paina | 0 | 4 (7) | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain upper | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 7 (13) | 2 (4) |

| Gastroenteritisa | 0 | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Insomniaa | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Dizzinessa | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Back pain | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | 0 | 3 (6) |

| Arthralgia | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 5 (9) |

| Headache | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 6 (11) | 3 (6) |

| Pyrexia | 4 (7) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Influenza | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 6 (11) |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Dry eye | 1 (2) | 0 | 5 (9) | 2 (4) |

Data are presented as n (%)

AE adverse event, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, DMF dimethyl fumarate, MS multiple sclerosis, PBO placebo

aOccurred at an incidence at least 2% higher in the DMF group than the PBO group

Table 3.

Serious adverse events that occurred during Part I

| Serious adverse events | PBO (n = 58) | DMF (n = 56) |

|---|---|---|

| Any | 11 (19) | 10 (18) |

| Pyelonephritis | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Anxiety | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Relapse of MS | 11 (19) | 7 (13) |

| Humerus fracture | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Tibia fracture | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Road traffic accident | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Fallopian tube cancer | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

Data are presented as n (%)

DMF dimethyl fumarate, MS multiple sclerosis, PBO placebo

AEs of Special Interest

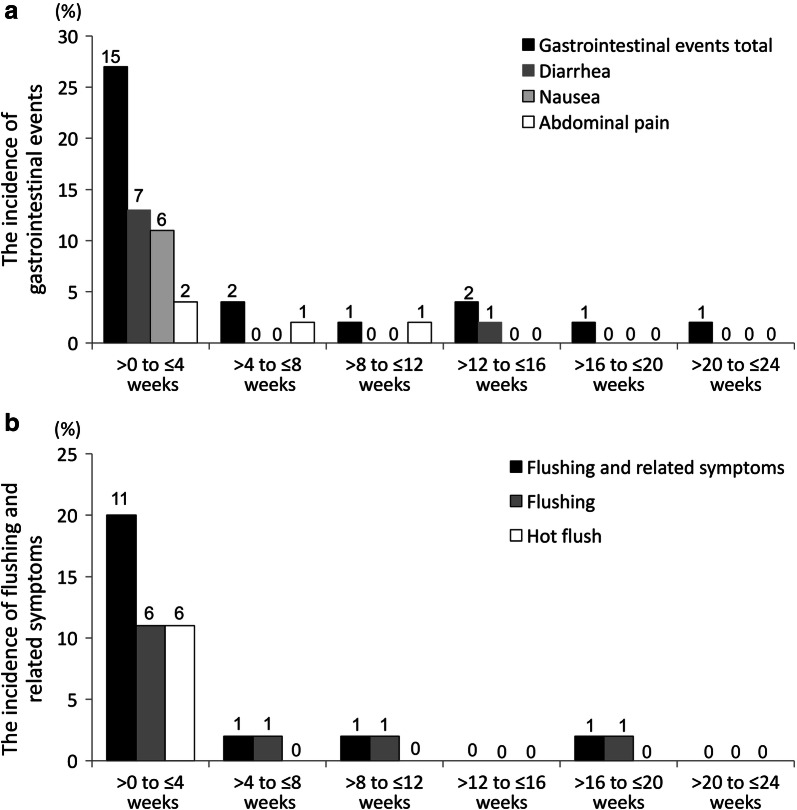

The majority of AEs of special interest were more common in the DMF group than in the PBO group; this included flushing and related events (DMF: n = 14, 25%; PBO: n = 3, 5%), gastrointestinal events (DMF: n = 20, 36%; PBO: n = 11, 19%), infections (DMF: n = 27, 48%; PBO: n = 24, 41%), cardiovascular events (DMF: n = 2, 4%; PBO n = 0) and hepatic events (DMF: n = 9, 16%; PBO: n = 4, 7%). No opportunistic infections were reported. The incidence of urinary events was similar in the two groups (DMF: n = 2, 4%; PBO: n = 3, 5%). One subject in the PBO group was diagnosed with cancer (ovarian neoplasm and fallopian tube cancer), while no malignancies were reported in the DMF group. Among subjects receiving DMF, the incidence of gastrointestinal events and flushing and related events was highest during the first month of treatment, but declined thereafter (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

a Incidence of gastrointestinal events that occurred in patients receiving dimethyl fumarate during Part I. b Incidence of flushing and related events that occurred in subjects receiving dimethyl fumarate during Part I. Data labels indicate the number of patients

Onset of Noteworthy AEs

During the first 4 weeks of the study, the median (earliest, latest) day of onset of gastrointestinal events was 10 (1, 14) for diarrhoea (n = 7), 10.5 (2, 28) for nausea (n = 6) and 10.5 (9, 12) for abdominal pain (n = 2); while the median (earliest, latest) day of onset of flushing and related symptoms was 1.5 (1, 2) for flushing (n = 6) and 1.0 (1, 1) for hot flush (n = 6), respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Onset of noteworthy adverse events within first 4 weeks during Part I (DMF group; n = 56)

| N | Onset (days) | Number of subjects, n | Median days (earliest, latest) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoea | |||

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 10 (1, 14) |

| 2 | 1 | ||

| 5 | 1 | ||

| 10 | 1 | ||

| 12 | 1 | ||

| 13 | 1 | ||

| 14 | 1 | ||

| Nausea | |||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 10.5 (2, 28) |

| 4 | 1 | ||

| 7 | 1 | ||

| 14 | 1 | ||

| 15 | 1 | ||

| 28 | 1 | ||

| Abdominal pain | |||

| 2 | 9 | 1 | 10.5 (9, 12) |

| 12 | 1 | ||

| Flushing | |||

| 6 | 1 | 3 | 1.5 (1, 2) |

| 2 | 3 | ||

| Hot flush | |||

| 6 | 1 | 6 | 1.0 (1, 1) |

Discontinuation Due to AE

During Part I, one subject in the DMF group discontinued treatment because of an AE (liver disorder), while two subjects in the PBO group discontinued treatment because of AEs (liver function test abnormal: n = 1; MS relapse: n = 1).

Part II

AEs and SAEs

At least one AE was reported by the majority of subjects during Part II (DMF/DMF: n = 48, 91%; PBO/DMF: n = 48, 91%; Table 2). Overall, the incidence of AEs in the PBO/DMF group was similar to that in the DMF group during Part I. SAEs were reported by eight subjects in the PBO/DMF group (15%) and seven subjects in the DMF/DMF group (13%; Table 5). Treatment-related AEs were also more common in the PBO/DMF group (n = 32, 60%) than in the DMF/DMF group (n = 25, 47%). At week 72, 52% of subjects in the PBO/DMF group and 41% of subjects in the DMF/DMF group experienced relapses of MS. The proportion of subjects who experienced at least one AE was higher in the PBO/DMF (79%) group than in the DMF/DMF group (64%) during the first 3 months of Part II; however, the difference declined thereafter (Table 6). The incidence of flushing, gastrointestinal and skin events as well as increases in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was similar in the PBO/DMF and DMF/DMF groups and remained stable throughout the study.

Table 5.

Serious adverse events that occurred during Part II

| Serious adverse events | PBO/DMF (n = 53) | DMF/DMF (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|

| Any | 8 (15) | 7 (13) |

| Appendicitis | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Suicide attempt | 0 | 1 (2) |

| MS relapse | 4 (8) | 5 (9) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Pregnancy | 1 (2) | 0 |

Data are presented as n (%)

DMF dimethyl fumarate, MS multiple sclerosis, PBO placebo

Table 6.

Adverse events that occurred with an incidence of 2% or higher during Part II by month

| Months | PBO/DMF | DMF/DMF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) with AE | N (%) | N (%) with AE | |

| 0–1 | 53 (100) | 36 (68) | 53 (100) | 26 (49) |

| > 1–2 | 53 (100) | 22 (42) | 53 (100) | 13 (25) |

| > 2–3 | 51 (100) | 13 (25) | 53 (100) | 17 (32) |

| > 3–4 | 50 (100) | 22 (44) | 53 (100) | 20 (38) |

| > 4–5 | 48 (100) | 12 (25) | 53 (100) | 18 (34) |

| > 5–6 | 46 (100) | 9 (20) | 53 (100) | 18 (34) |

| > 6–7 | 46 (100) | 11 (24) | 53 (100) | 19 (36) |

| > 7–8 | 45 (100) | 6 (13) | 52 (100) | 11 (21) |

| > 8–9 | 45 (100) | 11 (24) | 51 (100) | 14 (27) |

| > 9–10 | 44 (100) | 8 (18) | 50 (100) | 14 (28) |

| > 10–11 | 44 (100) | 6 (14) | 49 (100) | 11 (22) |

| > 11–12 | 44 (100) | 11 (25) | 49 (100) | 11 (22) |

Data are presented as n (%)

AE adverse event, DMF dimethyl fumarate, PBO placebo

AEs of Special Interest

The incidence of several AEs of special interest was higher in the PBO/DMF group than in the DMF/DMF group, including flushing and related events (26% vs 8%, respectively) and hepatic disorders (21% vs 11%, respectively). The incidences of other AEs of special interest were similar in the PBO/DMF and DMF/DMF groups (gastrointestinal AEs: 30% vs 28%; infections: 62% vs 64%; cardiovascular events: 6% vs 6%; renal disorders: 4% vs 4%; respectively). No opportunistic infections nor malignancies were reported during Part II.

Discontinuation Due to AEs

During Part II, one subject in the DMF/DMF group discontinued treatment because of an AE (MS relapse), while two subjects in the PBO/DMF group discontinued treatment because of AEs (abdominal pain: n = 1; increased ALT and AST: n = 1).

Laboratory Parameters During Part I and Part II

Lymphocyte Count

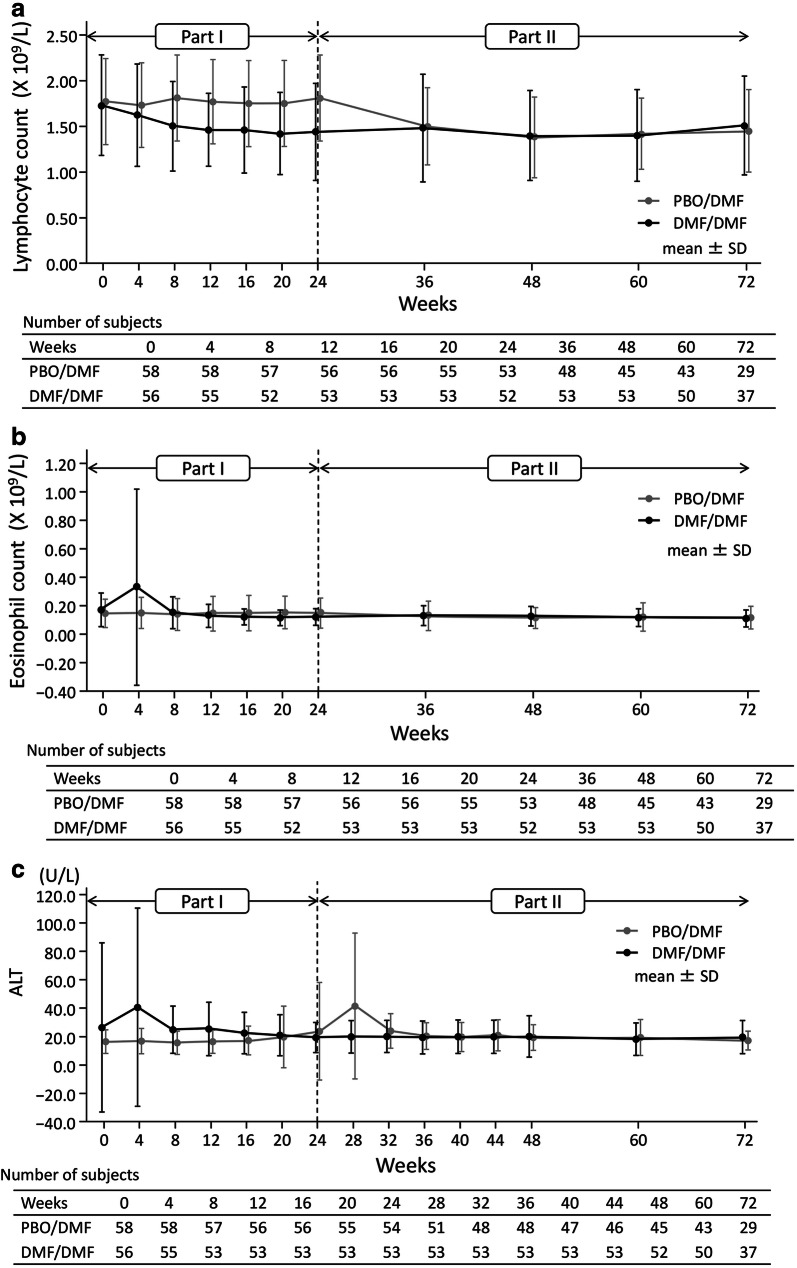

During Part I, mean lymphocyte count decreased in the DMF group by 17%, while it was stable in the PBO group (Fig. 2a). During Part II, mean lymphocyte count in the DMF/DMF group remained stable, while in the PBO/DMF group it declined to approximately the same level as in the DMF group during Part I.

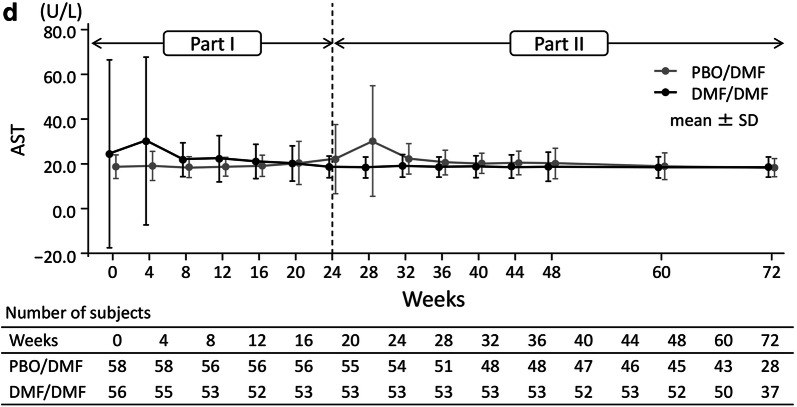

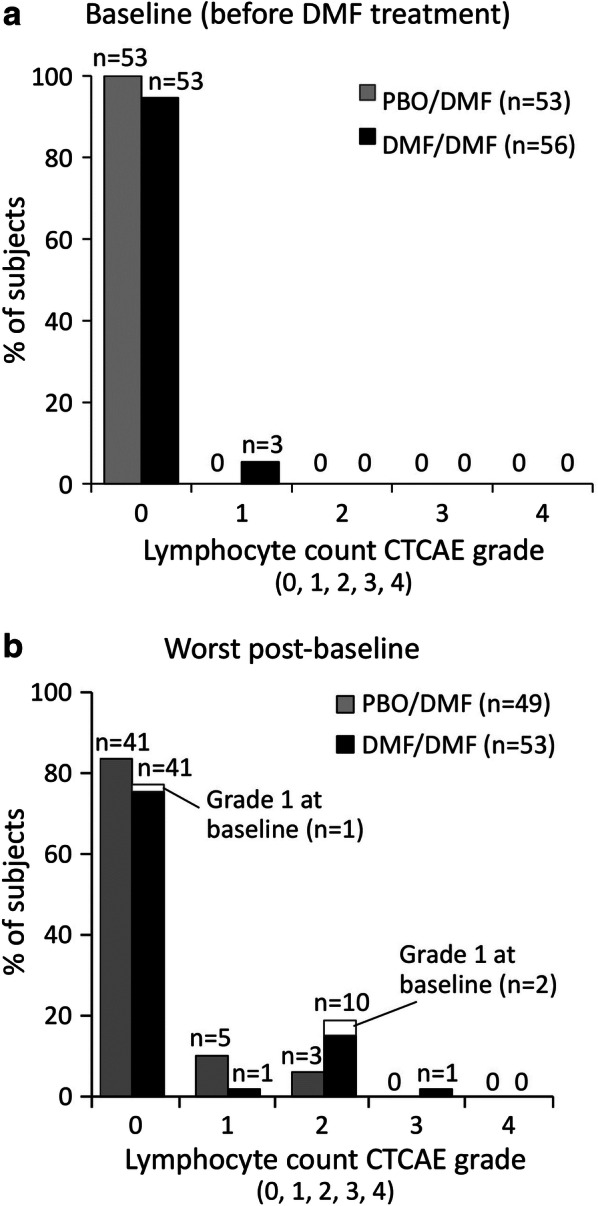

Fig. 2.

a Mean lymphocyte count during Part I and Part II. b Mean eosinophil count during Part I and Part II. c Mean alanine aminotransferase during Part I and Part II. d Mean aspartate aminotransferase during Part I and Part II. ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, DMF dimethyl fumarate, PBO placebo, SD standard deviation

Eosinophil Count

During Part I, a steep increase in eosinophil count was observed in the DMF group at 4 weeks, while no such increase was observed in the PBO group (Fig. 2b). This spike was considered temporary and the eosinophil counts were similar in the two groups for the remainder of the study.

ALT, AST

At week 4, an increase in ALT was observed in the DMF group during Part I, while in the PBO group, ALT levels remained stable (Fig. 2c). A similar increase was observed in the PBO/DMF group at week 28 of Part II. In both instances, ALT values normalised without treatment and no symptoms were observed at the next assessment. A similar pattern was observed for AST values (Fig. 2d).

Worst Post-Baseline Lymphocyte Count by CTCAE Grade

At the beginning of Part I, three subjects in the DMF/DMF group had a Grade 1 decrease in the lymphocyte count, while 53 subjects had normal lymphocyte counts. All subjects in the PBO/DMF group had normal lymphocyte counts at baseline (Fig. 3a). During the study, lymphocyte count never decreased below the lower limit of normal (LLN) in 84% of subjects (41/49) in the PBO/DMF group and 77% of subjects (41/53) in the DMF/DMF group. Of the three subjects in the DMF/DMF group who had Grade 1 decrease in lymphocyte count at the beginning of Part II, two patients developed a Grade 2 decrease in lymphocyte count, while in the other patient, the lymphocyte count did not decrease below the LLN during Part II. Grade 3 decreases in lymphocyte count were recorded in one subject in the DMF/DMF group during Part II (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

a Baseline lymphocyte count by CTCAE grade. Data labels indicate the number of subjects. b Worst post-baseline lymphocyte count by CTCAE grade. Data labels indicate the number of subjects. CTCAE common terminology criteria for adverse events, DMF dimethyl fumarate, PBO placebo, LLN lower limit of normal. Categories by lymphocyte counts (×109 cells/L): 0: LLN (0.91); 1: < LLN to 0.8; 2: < 0.8 to 0.5; 3: < 0.5 to 0.2; 4: < 0.2

Discussion

The present interim analysis of the APEX study is the first report to assess the safety of DMF in Japanese subjects with RRMS over a 72-week period. The results of this analysis indicate that DMF was well tolerated in this subject population. The incidences of AEs and SAEs, as well as the number of subjects who discontinued study treatment because of AEs, were similar between the DMF and PBO groups during Part I and between the DMF/DMF and PBO/DMF groups during Part II. Treatment-related AEs were more common in the DMF group in Part I and in the PBO/DMF group in Part II, reflecting the fact that most such AEs occurred during the first months of DMF therapy. MS relapses were more common in the PBO group during Part I and in the PBO/DMF group during Part II.

The results of this study are consistent with published literature. The overall incidences of AEs in the PBO and the DMF twice daily groups in the DEFINE study were 95% and 96%, respectively [9], and in the CONFIRM study they were 92% and 94%, respectively [8]. In addition, the proportions of patients who experienced an SAE in the PBO and the DMF twice daily groups were 21% and 18%, respectively, in the DEFINE study [9] and 22% and 17%, respectively, in the CONFIRM study [8]. In the present study, 84% of patients in the PBO group and 95% of patients in the DMF group experienced at least one AE during Part I, while 19% of patients in the PBO group and 18% of patients in the DMF group experienced SAEs. Therefore, the results of the present study are in line with those of pivotal studies and indicate that, in subjects with RRMS, the overall incidence of AEs and SAEs with DMF is similar to that with PBO.

ENDORSE is a long-term extension study that combines the patient cohorts of DEFINE and CONFIRM studies [10]. At 5 years of follow-up, the incidences of AEs and SAEs in patients who were randomised to DMF twice daily during one of the main studies and then continued to receive DMF twice daily during ENDORSE were 91% and 22%, respectively, while in patients who were initially randomised to PBO and then switched to DMF twice daily, they were 95% and 24%, respectively [10]. In the current APEX interim analysis, the duration of follow-up was shorter than in ENDORSE, but the incidences of AEs (PBO/DMF: 91%; DMF/DMF: 91%) and SAEs (PBO/DMF: 15%; DMF/DMF: 13%) were broadly similar and continued the trend towards fewer SAEs with DMF compared with PBO that was observed in short-term studies. A more adequate comparison will be performed once the final data from the APEX study (4.5 years) are available.

AEs that had an incidence of 2% higher in the DMF group than the PBO group during Part I of the present study include flushing (14% vs 3%) and gastrointestinal events such as diarrhoea (14% vs 9%), nausea (11% vs 7%), vomiting (5% vs 0%), abdominal pain (7% vs 0%) and gastroenteritis (5% vs 0%). These findings are also consistent with the results of pivotal trials, where flushing and gastrointestinal events were identified as the most common AEs associated with DMF therapy [8, 9].

At week 72, 52% of subjects in the PBO/DMF group and 41% of subjects in the DMF/DMF group had relapses of MS. These results may seem higher than in previous studies with DMF [8, 9], but this was most likely due to the differences in baseline disease activity of subjects. For example, in the integrated analysis of DEFINE and CONFIRM in Caucasian subjects at 2 years, MS relapse occurred in 47% and 44% of patients in the two studies’ placebo groups, and in 29% and 28% of patients in the DMF groups, respectively [15]. At the end of the 24-week placebo-controlled period of APEX, the proportion of subjects with a relapse of MS was 47% in the placebo group and 29% in the DMF group, which are similar to 2-year results of the DEFINE and CONFIRM studies [15]. However, this does not imply lower efficacy of DMF in a Japanese population, since DMF reduced the annualised rate of relapse (ARR) by 48% at 24 weeks in APEX, comparable to the 49% reduction in ARR at 2 years in DEFINE and CONFIRM [15].

The difference between the APEX findings and the DEFINE/CONFIRM findings cannot be attributed to pharmacokinetic differences between Japanese and Caucasian patients, because data suggest that the pharmacokinetics of DMF are similar in Japanese and non-Japanese patients. A phase 1 study found no significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of monomethyl fumarate, a metabolite of DMF, among Japanese, Chinese and Caucasian participants (unpublished data).

Most AEs of special interest occurred during the first weeks of treatment with DMF and resolved without intervention. The incidence of flushing, as well as gastrointestinal events, was lower during Part I of the present study (14%) compared with patients who received DMF twice daily in the DEFINE (38%) [9] and CONFIRM (31%) studies [8]. However, it should be noted that the duration of these pivotal studies was 2 years while the duration of Part I of the present study was 24 weeks, which could have affected the frequency of these AEs. Other possible explanations include administration of DMF with food in the APEX study. Because flushing develops on the same or the next day after administration, it is thought to result from an acute inflammatory reaction that is, at least in part, prostaglandin-mediated [16]. It may be that Japanese patients have a relatively lower propensity for this response. Furthermore, it might be more difficult to identify flushing in some Japanese patients compared with Caucasians because of the fairer skin of the latter. In addition, mean eosinophil count and the levels of ALT and AST at week 4 after DMF initiation increased in the DMF group during Part I and in the PBO/DMF group during Part II. These increases were transient and asymptomatic in both instances and resolved without any intervention. Furthermore, the magnitude of the decreases in lymphocyte count observed in the present study (17%) were lower than in an integrated analysis that included a Phase IIb study, as well as DEFINE, CONFIRM and ENDORSE (approx. 30%) [17]. This lymphocyte count decrease did not lead to discontinuation of DMF in the present study. Currently available data indicate that flushing, gastrointestinal events, reduction of lymphocyte count and increased ALT and AST levels are commonly associated with DMF therapy. Close monitoring of these events is essential: flushing and gastrointestinal events should be monitored during the first 3 months of treatment, lymphocyte count and complete blood count should be monitored at baseline followed by at least every 3 months, and liver and renal function tests at baseline and regularly throughout the treatment period [18]. In addition, recommendations for the management of gastrointestinal events associated with DMF therapy in RRMS patients have been developed by a panel of investigators from the DEFINE and CONFIRM studies and a Delphi panel of US clinicians [19]. These recommendations include educating patients about the adverse events associated with DMF therapy before treatment initiation, administering DMF with food, slow titration and dose reduction, as well as symptomatic treatment. A study conducted in German patients with MS reported improved adherence to DMF therapy with individualised patient counselling programs [20].

The main limitation of the present interim analysis was the relatively low number of patients. This may have prevented detection of rare AEs. This shortcoming may be addressed in an ongoing all-case surveillance program currently being conducted under real-world conditions in Japan.

Conclusions

The results of the present interim analysis of the randomised, placebo-controlled APEX study and its open-label extension demonstrate that DMF has a favourable safety profile in Japanese patients with RRMS, with fewer patients developing flushing and related symptoms and a lower reduction in lymphocyte count compared with previous studies conducted in mostly Caucasian patients with RRMS.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to all physicians who were involved in the APEX studies, and sincerely thank the patients who participated in this study and acknowledge their contributions.

Funding

The study, medical writing of the manuscript, article processing charges and open access fee was funded by Biogen Japan Ltd. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

The authors thank Georgii Filatov, of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, for writing the first and second drafts of this manuscript. This medical writing assistance was funded by Biogen Japan Ltd.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

HO contributed to patient recruitment and data collection, analysis and interpretation. MN contributed to patient recruitment, and data collection and interpretation. YO, KH, MH contributed to data analysis and interpretation. MA and ST contributed to data interpretation. JY is the lead statistician for this study and performed statistical analyses to provide all data included in this manuscript, and contributed to the interpretation of these data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Disclosures

Hirofumi Ochi is a scientific advisory board member of Biogen Japan Ltd. and has received honoraria from Bayer Yakuhin Ltd., Novartis Pharma K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp., Asahi Kasei Medical Co., Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Masaaki Niino has received honoraria from Bayer Yakuhin Ltd., Biogen Japan Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Fujifilm RI Pharma Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp, Novartis Pharma K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Terumo Corp. Yasuhiro Onizuka is an employee of Biogen Japan Ltd. and a stockholder of Biogen Inc. Katsutoshi Hiramatsu is an employee of Biogen Japan Ltd. and a stockholder of Biogen Inc. Shinichi Torii is an employee of Biogen Japan Ltd. and a stockholder of Biogen Inc. Masakazu Hase was an employee of Biogen Japan Ltd. and a stockholder of Biogen Inc. at the time of this study conducted, but is now affiliated with Gtheranostics Co., Ltd. Jang Yun was an employee of Biogen Inc. and a stockholder of Biogen Inc. at the time of this study conducted but is now affiliated with Theravance Biopharma Inc. André Matta is an employee and a stockholder of Biogen Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by ethics committees at all sites and conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before any evaluations or procedures were performed.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Biogen Data Request Portal repository, https://biogen-dt-external.pharmacm.com/DT/Home/Index/.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital content

To view enhanced digital content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7028819.

References

- 1.Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1502–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas of MS 2013: mapping multiple sclerosis around the World. http://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Atlas-of-MS.pdf. Accessed 17 Apr 18.

- 3.Ochi H, Fujihara K. Demyelinating diseases in Asia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016;29(3):222–8. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SH, Kim HJ. Central nervous system neuroinflammatory disorders in Asian/Pacific regions. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016;29(3):372–80. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linker RA, Haghikia A. Dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis: latest developments, evidence and place in therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7(4):198–207. 10.1177/2040622316653307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onizuka Y, Hiramatsu K, Hase M, et al. Review of dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®) Part 2: safety in patients with multiple sclerosis. [in Japanese]. Med Consult New Remedies. 2017;54(9):883–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.AdisInsight. Dimethyl fumarate—Biogen [last updated 12 January 2018]. http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800019706. Accessed 23 Jan 2018.

- 8.Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1087–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa1206328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1098–107. 10.1056/NEJMoa1114287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold R, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, et al. Long-term effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis: interim analysis of ENDORSE, a randomized extension study. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2):253–65. 10.1177/1352458516649037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saida T, Yamamura T, Kondo T, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis from Asia-Pacific and other countries. Mult Scler J. 2016;22(3_suppl):P607. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saida T, Yamamura T, Kondo T, et al. Safety and efficacy of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis from East Asia and other countries: interim analysis of the APEX extension study. Neurology. 2017;88(16 Suppl):363. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald criteria”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(6):840–6. 10.1002/ana.20703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46(4):907–11. 10.1212/WNL.46.4.907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viglietta V, Miller D, Bar-Or A, et al. Efficacy of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: integrated analysis of the phase 3 trials. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2(2):103–18. 10.1002/acn3.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikh SI, Nestorov I, Russell H, et al. Tolerability and pharmacokinetics of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate administered with and without aspirin in healthy volunteers. Clin Ther. 2013;35(10):1582 e9–1594 e9. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox RJ, Chan A, Gold R, et al. Characterizing absolute lymphocyte count profiles in dimethyl fumarate-treated patients with MS: patient management considerations. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6(3):220–9. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biogen. TECFIDERA®(dimethyl fumarate) delayed-release capsules, for oral use. Highlights of prescribing information. https://www.tecfidera.com/content/dam/commercial/multiple-sclerosis/tecfidera/pat/en_us/pdf/full-prescribing-info.pdf. Accessed 17 Apr 18.

- 19.Phillips JT, Erwin AA, Agrella S, et al. Consensus management of gastrointestinal events associated with delayed-release dimethyl fumarate: a Delphi study. Neurol Ther. 2015;4(2):137–46. 10.1007/s40120-015-0037-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mäurer M, Voltz R, Begus-Nahrmann Y, et al. Adherence project with German MS-patients: can an approach of individualized patient counseling improve adherence? Mult Scler J. 2014;20(1_suppl):P305. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Biogen Data Request Portal repository, https://biogen-dt-external.pharmacm.com/DT/Home/Index/.