Abstract

Introduction

Assessing clinically important measures of disease progression is essential for evaluating therapeutic effects on disease stability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This analysis assessed whether providing additional bronchodilation with the long-acting muscarinic antagonist umeclidinium (UMEC) to patients treated with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) therapy would improve disease stability compared with ICS/LABA therapy alone.

Methods

This integrated post hoc analysis of four 12-week, randomized, double-blind trials (NCT01772134, NCT01772147, NCT01957163, NCT02119286) compared UMEC 62.5 µg with placebo added to open-label ICS/LABA in symptomatic patients with COPD (modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale score ≥ 2). A clinically important deterioration (CID) was defined as: a decrease from baseline of ≥ 100 mL in trough forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), an increase from baseline of ≥ 4 units in St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score, or a moderate/severe exacerbation. Risk of a first CID was evaluated in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population and in patients stratified by Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification, exacerbation history and type of ICS/LABA therapy. Adverse events (AEs) were also assessed.

Results

Overall, 1637 patients included in the ITT population received UMEC + ICS/LABA (n = 819) or placebo + ICS/LABA (n = 818). Additional bronchodilation with UMEC reduced the risk of a first CID by 45–58% in the ITT population and all subgroups analyzed compared with placebo (all p < 0.001). Improvements were observed in reducing FEV1 (69% risk reduction; p < 0.001) and exacerbation (47% risk reduction; p = 0.004) events in the ITT population. No significant reduction in risk of a SGRQ CID was observed. AE incidence was similar between treatment groups.

Conclusion

Symptomatic patients with COPD receiving ICS/LABA experience frequent deteriorations. Additional bronchodilation with UMEC significantly reduced the risk of CID and provided greater short-term stability versus continued ICS/LABA therapy in these patients.

Funding

GlaxoSmithKline (study number: 202067).

Plain Language Summary

Plain language summary available for this article.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-018-0771-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Add-on LAMA, Clinically important deteriorations, COPD, Fluticasone furoate/vilanterol, Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol, Respiratory, Triple therapy, Umeclidinium

Plain Language Summary

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) describes a group of lung conditions characterized by the narrowing of airways, which cause progressive breathing difficulties and persistent symptoms of breathlessness. COPD causes irreversible lung damage; however, numerous treatment options can alleviate symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life. Inhaled long-acting bronchodilators are the mainstay of COPD medication as they open the airways to reduce chronic symptoms. In addition, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) can help reduce airway inflammation, and, in combination with long-acting β2-agonist bronchodilator (LABA) therapy, reduce the added risk of acute exacerbations (acute worsening of symptoms requiring additional medical care). The ICS/LABA combination may be combined with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) bronchodilator in patients with severe COPD.

The benefits of using two bronchodilators with complimentary efficacy in combination with ICS was explored in this study, looking at the incidence of clinically important deterioration (CID). CID is a new exploratory measure of deterioration, which examines different types of significant worsening in lung function, patient health status and exacerbation events. This study assessed whether CID events can be prevented by adding once-daily LAMA umeclidinium (UMEC) to the treatment of patients remaining symptomatic on ICS/LABA combination therapy.

We found that the risk of a first CID event of any type was reduced by approximately half in symptomatic patients receiving UMEC + ICS/LABA compared with placebo + ICS/LABA therapy, with particular benefits in stabilizing the patients’ risk of future lung function deteriorations and reducing acute exacerbations.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a frequently progressive disease characterized by persistent airflow obstruction, represents a major contributor to global morbidity and mortality [1–3]. A high symptom burden in patients with COPD, in particular high levels of dyspnea with or without frequent use of short-acting rescue medication, is associated with poor quality of life (QoL), increased risk of exacerbations, and a substantial increase in the economic burden of the disease [4–8].

The mainstay of pharmacotherapy for COPD is bronchodilation with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA), or a combination of the two [9, 10]. For patients with a high symptom burden and a history of exacerbations, a recommended [1] and relatively common [11–13] therapeutic approach is the co-administration of a LAMA, a LABA, and an ICS as triple therapy. This approach has demonstrated reductions in the risks of hospitalization and all-cause mortality when compared with ICS/LABA combination therapy in large, non-randomized cohort studies [11, 14].

The efficacy of the LAMA and ICS/LABA components of triple therapy versus placebo have been well demonstrated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [15, 16]. Available data from RCTs of triple therapy have demonstrated improvements in lung function and health status and reduced use of rescue medication, with no increased safety concerns, in symptomatic patients receiving additional bronchodilation with a LAMA added to ICS/LABA therapy compared with those continuing ICS/LABA therapy alone [17, 18]. More recently, limited data from RCTs have demonstrated that the addition of a LAMA to ICS/LABA therapy reduces exacerbation incidence [19, 20]. However, the impact of adding additional bronchodilation with a LAMA to symptomatic patients using ICS/LABA therapy to maintain disease stability beyond preventing exacerbations is not well understood.

According to the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report, the goals of the management of COPD are to reduce daily symptoms and to reduce the future risk of poor outcomes [1]. One key component of achieving these goals is to ensure optimal disease management by regular monitoring of patients to assess the adequacy of their current therapy in maintaining lung function stability and symptom control, as well as minimizing the incidence of exacerbations [1]. Clinical trials in COPD usually evaluate improvements in spirometry, symptoms and QoL. However, improvements in these parameters are not always observed, and many patients may not respond to treatment [21] and can experience deterioration of their disease without the occurrence of acute exacerbations. It is therefore important to assess both improvement and deterioration so that levels of disease stability and instability in patients receiving any new treatment can be quantified; this approach is consistent with the management goals set out in the GOLD report [1].

In order to compare the effects of therapies on short-term stability, a novel composite endpoint assessing three dimensions of CID (lung function, health status, and exacerbations) has been described [22]. This composite endpoint has been used to demonstrate improved stability after increasing bronchodilation in symptomatic patients using dual fixed-dose LAMA/LABA combination therapies compared with placebo, ICS/LABA therapy or LAMA or LABA monotherapies [21–23].

To build upon these results, this integrated post hoc analysis of four short-term double-blind efficacy trials of replicate design aimed to assess the impact of providing additional bronchodilation with the LAMA umeclidinium (UMEC) versus placebo in preventing CIDs in patients who remained symptomatic on ICS/LABA therapy. A previous integrated post hoc analysis of the four studies included in this analysis demonstrated improvements in lung function and QoL, and reduced rescue medication use, in patients using ICS/LABA therapy who received additional bronchodilation with UMEC versus placebo [18]. This analysis will assess whether the improvements observed in these outcomes will translate to improved stability and reductions in short-term CIDs.

Methods

Study Design

This was an integrated post hoc analysis (GSK study number: 202067) of four 12-week, Phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trials comparing UMEC + ICS/LABA with placebo + ICS/LABA [24, 25]. Once-daily UMEC (62.5 or 125 µg) or placebo were administered double-blind via the ELLIPTA dry powder inhaler (DPI). The ICS/LABA combinations investigated were twice-daily fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (FP/SAL) 250/50 µg administered via the DISKUS DPI (trials AC4116135 [NCT01772134] and AC4116136 [NCT01772147]) [24] and once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (FF/VI) 100/25 µg administered via the ELLIPTA DPI [trials 200109 (NCT01957163) and 200110 (NCT02119286)] [25]. ELLIPTA and DISKUS are owned by or licensed to the GSK group of companies.

All studies had a replicate design, as previously reported [24, 25], whereby enrolled patients entered a 4-week open-label run-in treatment period with once- or twice-daily ICS/LABA. At the end of this period, patients without a COPD exacerbation, who did not use any prohibited medications, and who were 80–120% compliant with the open-label ICS/LABA were randomized to receive additional bronchodilation with UMEC or matching placebo added to their ICS/LABA treatment for a further 12 weeks. Only the results from the approved dose of UMEC (62.5 µg) [26, 27] are presented here. In the original studies, the two doses of UMEC were shown to have similar efficacy and safety profiles when added to ICS/LABA therapy [24, 25].

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. The study presented was an integrated post hoc analysis of four clinical trials all conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before participation in the studies considered in this analysis.

Patients

Key inclusion criteria for all studies included in this analysis were as follows [24, 25]: patients ≥ 40 years of age with an established clinical history of COPD in accordance with the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society definition [28], classified as Group B or D according to the GOLD 2016 strategy document [29]; a current or former smoker with a smoking history of ≥ 10 pack-years; a predicted post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) of ≤ 70%; a FEV1/forced vital capacity ratio of < 0.70 at first visit; and a score of ≥ 2 on the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale at first visit. Key exclusion criteria included [24, 25]: a diagnosis of asthma or another known clinically relevant respiratory disease (other than COPD); and hospitalization for COPD or pneumonia in the 12 weeks prior to first visit.

Outcomes and Assessments

The primary endpoint for all four studies was trough FEV1 on day 85 in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population. Other endpoints included: St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score; incidence of exacerbations (defined as any acute worsening of COPD symptoms requiring the use of antibiotics, systemic corticosteroids, emergency treatment or hospitalization); and the proportions of patients achieving improvements of ≥ 100 mL in trough FEV1 or ≥ 4 units in SGRQ score, respectively. Adverse events (AEs) after the run-in period were assessed in all studies; AEs of special interest included those associated with the use of LAMAs.

A first CID was defined as any of the following: decrease of ≥ 100 mL from baseline in trough FEV1; increase of ≥ 4 units in SGRQ total score from baseline; or a moderate/severe exacerbation. In this analysis, the risk of a first CID of each type and a first composite CID were evaluated in the ITT population, and in patients stratified by GOLD Group B and D, exacerbation history at screening and type of ICS/LABA therapy. AEs are presented for the pooled ITT populations.

Statistical Analyses

The time to the first deterioration based on the composite endpoint was taken as the time to the first deterioration event of any component. Hazard ratios (HR), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values for the treatment comparisons of UMEC + ICS/LABA versus placebo + ICS/LABA were calculated based on the time to first event using a Cox proportional hazards model with covariates of treatment, study and smoking status at screening. Kaplan–Meier survivor functions of the proportion of subjects with deterioration over time were obtained separately for each treatment group. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

In total, 1637 patients were randomized to UMEC 62.5 µg + ICS/LABA (n = 819) or placebo + ICS/LABA (n = 818) and received at least one dose of study medication (ITT population). Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were similar across the two treatment groups (Table 1), with mean [standard deviation (SD)] ages of 63.7 (8.3) and 64.1 (8.4) years in the UMEC + ICS/LABA and placebo + ICS/LABA groups, respectively. The majority of patients in both the UMEC + ICS/LABA and placebo + ICS/LABA groups were male (67% and 64%, respectively) and classified as GOLD Group D according to the GOLD 2016 classifications [29] (61% and 58%, respectively). Patient clinical characteristics were also similar across the two treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics (ITT population).

Adapted from: Siler et al. [18]

| Characteristics | UMEC 62.5 µg + ICS/LABA (n = 819) | Placebo + ICS/LABA (n = 818) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.7 (8.3) | 64.1 (8.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 547 (67) | 521 (64) |

| Current smoker at screeninga, n (%) | 376 (46) | 402 (49) |

| Smoking history, pack-yearsb | 47.8 (26.2) | 47.6 (25.6) |

| Baseline pre-bronchodilator FEV1, L | 1.26 (0.47) | 1.27 (0.48)c |

| GOLD B patients | 1.59 (0.42) | 1.60 (0.44) |

| GOLD D patients | 1.05 (0.37) | 1.03 (0.35) |

| Post-albuterol % predicted FEV1 | 45.3 (12.4) | 46.4 (13.0) |

| Reversible patientsd, n (%) | 265 (32)e | 235 (29) |

| GOLD groupf, n (%) | ||

| B | 320 (39) | 344 (42) |

| D | 499 (61) | 474 (58) |

| With FEV1 < 50% predicted, n (%) | 478 (96) | 464 (98) |

| With FEV1 < 30% predicted, n (%) | 94 (19) | 108 (23) |

| With ≥ 1 exacerbationsg, n (%) | 122 (24) | 115 (24) |

| With ≥ 2 exacerbationsg, n (%) | 46 (9) | 32 (7) |

| Moderate exacerbationsg in 12 months prior to screening, n (%) | 160 (20) | 162 (20) |

| Puffs of albuterol per dayh | 2.2 (2.8) | 2.0 (2.5) |

| SGRQ total score | 44.6 (17.2) | 44.6 (17.5) |

| ICS/LABA treatment during run-in, n (%) | ||

| FF/VI | 412 (50) | 412 (50) |

| FP/SAL | 407 (50) | 406 (50) |

Values are reported as mean (SD) unless otherwise stated

FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FF fluticasone furoate, FP fluticasone propionate, GOLD Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, ITT intent-to-treat, LABA long-acting β2-agonist, mMRC modified Medical Research Council, SAL salmeterol, SD standard deviation, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, UMEC umeclidinium, VI vilanterol

aSmoked within 6 months

bSmoking history defined as (number of cigarettes smoked per day/20) × number of years smoked

cn = 815

dReversibility defined as increase in FEV1 of ≥ 12% and ≥ 200 mL following administration of albuterol

en = 818

fClassified by criteria presented in GOLD 2016 update [29] using mMRC ≥ 2 as the criterion for high symptom burden; definition included percent predicted FEV1 as a severity marker (i.e., patients could be included in Group D with an FEV1 < 50% predicted)

gExacerbations defined as those requiring oral/systemic corticosteroids and/or antibiotics, but not involving hospitalization

hMean puffs/day during last 7 days of run-in

Incidence of CIDs

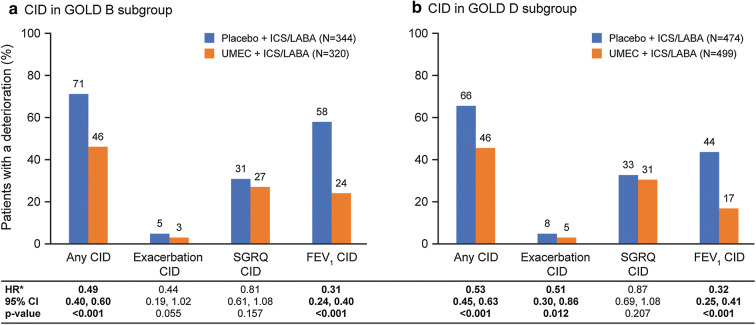

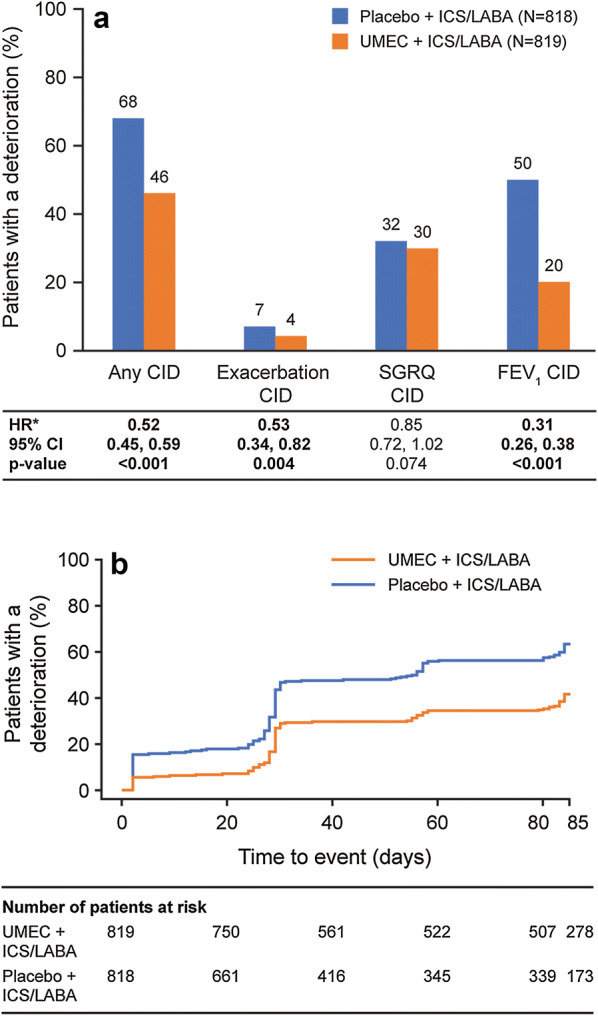

The proportion of patients in the ITT population experiencing any CID was higher in the placebo + ICS/LABA group than in the UMEC + ICS/LABA group (68% vs. 46%; Fig. 1a). For both any CID and risk of first CID event, the most common cause of deterioration in the ITT population and patients stratified by subgroup analyses were FEV1 CID events in the placebo + ICS/LABA group and SGRQ CID events in the UMEC + ICS/LABA group; the least common was exacerbation CID events in both treatment groups (Figs. 1a, 2, 3; Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of CIDs in the ITT population. a Type of deterioration; b Kaplan–Meier plot of time to first composite CID. *HR and 95% CI based on a time to first event analysis using a Cox’s proportional hazards model. CI confidence interval, CID clinically important deterioration, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, HR hazard ratio, ICS/LABA inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, UMEC umeclidinium

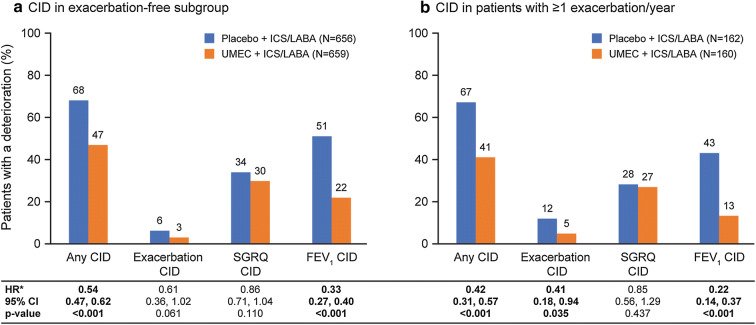

Fig. 2.

Analysis of CIDs stratified by GOLD 2016 groupsa. aClassified by criteria presented in GOLD 2016 update [29]; definition included percent predicted FEV1 as a severity marker (i.e., patients could be included in Group D with an FEV1 < 50% predicted). *HR and 95% CI based on a time to first event analysis using a Cox’s proportional hazards model. CI confidence interval, CID clinically important deterioration, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, HR hazard ratio, ICS/LABA inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, UMEC umeclidinium

Fig. 3.

Analysis of CIDs stratified by exacerbation historya. aExacerbation-free patients were defined as those with no history of exacerbations requiring oral/systemic corticosteroids and/or antibiotics. *HR and 95% CI based on a time to first event analysis using a Cox’s proportional hazards model. CI confidence interval, CID clinically important deterioration, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, HR hazard ratio, ICS/LABA inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist, SGRQ St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, UMEC umeclidinium

Risk of a First CID

ITT Population

At any given time point, the probability of patients experiencing a CID was lower for patients receiving UMEC + ICS/LABA than those receiving placebo + ICS/LABA (Fig. 1b). In the ITT population, the risk of a first CID of any type was reduced by 48% (95% CI 41, 55; p < 0.001) in patients stepping up to UMEC + ICS/LABA compared with placebo + ICS/LABA (Fig. 1a). Significant reductions in the risk of a first CID were observed in patients receiving additional bronchodilation with UMEC for both FEV1 events [69% (95% CI 62, 74) risk reduction; p < 0.001] and exacerbation events [47% (95% CI 18, 66) risk reduction; p = 0.004]. However, the reduction in the risk of a SGRQ CID was not significant [15% (95% CI − 2, 28) risk reduction; p = 0.074].

Patients Stratified by GOLD 2016 Group B and D

Addition of UMEC to ICS/LABA therapy significantly reduced the risk of a composite first CID in patients classified as GOLD Groups B and D according to the classifications in the 2016 guidelines [29] (Fig. 2). The magnitudes of the reductions in risk of experiencing a composite CID or a CID of any component of the composite endpoint were generally similar between the patients in GOLD Groups B and D. Significant reductions in the risk of a first CID were observed in patients receiving additional bronchodilation with UMEC therapy in both GOLD groups for FEV1 events (p < 0.001) and in patients in the GOLD Group D for exacerbation events (p = 0.012); however, no significant reduction in the risk of a SGRQ event was observed in patients in either GOLD group.

Patients Stratified by Exacerbation History

Addition of UMEC to ICS/LABA therapy significantly reduced the risk of a composite first CID in patients with a history of exacerbations and in those with no prior exacerbations in the 12 months prior to screening (Fig. 3). The magnitudes of the reductions in risk of experiencing a composite CID or a CID of any component of the composite endpoint were similar in patients with and without a history of exacerbations. However, the reduction in risk of a first exacerbation CID event with additional bronchodilation with UMEC was only statistically significant in patients with a prior exacerbation history (p = 0.035). Significant reductions in the risk of a first CID with additional UMEC therapy were also observed in patients with and without a history of exacerbations for FEV1 events (p < 0.001); however, no significant reduction in the risk of a SGRQ event was observed in either subgroup.

Patients Stratified by Type of ICS/LABA Therapy

The reductions in the risk of a composite CID, and in the risk of a CID of any type, observed with additional bronchodilation with UMEC therapy were generally consistent between patients receiving once-daily FF/VI and those receiving twice-daily FP/SAL (Supplementary Fig. 1). Significant reductions in the risk of a first CID with UMEC + ICS/LABA versus placebo + ICS/LABA were observed in patients receiving both FF/VI and FP/SAL for FEV1 events (p < 0.001) and in patients receiving FF/VI for exacerbation events (p = 0.033); however, no significant reduction in the risk of a SGRQ event was observed in either ICS/LABA subgroup.

Safety

As previously reported [18], the incidence of any on-treatment AEs in the ITT population was similar between the two treatment groups (UMEC + ICS/LABA: 36%; placebo + ICS/LABA: 38%). Likewise, incidences of serious AEs (SAEs; non-fatal and fatal; any event) were low and similar between the two treatment groups (non-fatal SAEs: 2% vs. 4%; fatal SAEs: < 1% vs. < 1%, for UMEC + ICS/LABA and placebo + ICS/LABA, respectively). The most commonly reported AEs (by ≥ 3% of patients) were nasopharyngitis (UMEC + ICS/LABA: 4%; placebo + ICS/LABA: 6%), headache (UMEC + ICS/LABA: 4%; placebo + ICS/LABA: 4%), and back pain (UMEC + ICS/LABA: 3%; placebo + ICS/LABA: 2%). The incidences of AEs of special interest [pneumonia, lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) excluding pneumonia and cardiovascular events] in patients receiving UMEC were similar to or lower than those in the group receiving placebo (pneumonia: < 1% vs. 1%; LRTI excluding pneumonia: < 1% vs. < 1%; cardiovascular events: 2% vs. 4%, respectively).

Discussion

Escalation of bronchodilator treatment in patients who remain symptomatic on ICS/LABA is a common treatment strategy for COPD [1]. Improvements in lung function and health status with additional bronchodilation with UMEC added to ICS/LABA combination therapy compared with ICS/LABA therapy alone have been previously reported [18]. The results of this complementary integrated retrospective analysis now demonstrate that, compared with placebo, the additional bronchodilation afforded by the addition of UMEC to ICS/LABA combination therapy reduced the short-term risk of clinically important worsening in lung function and exacerbations in patients with persistent symptomatic moderate-to-severe COPD. These improvements in stability were consistent between patients in different GOLD groups (based upon the definition in the 2016 report [29]), patients with and without a history of exacerbations, and patients receiving either the ICS/LABA combination FF/VI once daily or FP/SAL twice daily.

As a full interpretation of the composite CID endpoint requires examination of the individual component events, we examined the impact of treatment on all three components of the CID: loss of lung function, decline in health status, and incidence of exacerbations. Of these components, it was observed that additional bronchodilator therapy with UMEC had the greatest impact on reducing the risk of deteriorations in trough FEV1 in all subgroups of patients (63–78% reduction). Reductions in the risk of a first moderate/severe exacerbation were also observed with UMEC + ICS/LABA therapy versus placebo + ICS/LABA across the overall population and in all subgroups analyzed (39–59% reduction). The magnitude of risk reductions was similar across the subgroups; however, statistical significance was not always observed, for example, in patient subgroups with a low risk of exacerbation and/or FEV1 ≥ 50% predicted normal. No statistically significant impact of additional bronchodilation with UMEC therapy on the reduction in deterioration in health status assessed by SGRQ total score was observed in the overall population or any subgroup over the short assessment period.

A relationship between incidence of short–term deteriorations and poorer long–term outcomes has been demonstrated using data from several long-term studies, including the TORCH (NCT00268216) [16, 30], ECLIPSE (NCT00292552) [31], and UPLIFT (NCT00144339) [15] trials [32, 33]. These post hoc prognostic analyses have consistently shown that patients who experience short-term CID events are at a higher risk of future severe exacerbations and mortality. The enhanced short-term stability reported here may therefore highlight important long-term benefits of providing additional bronchodilation with UMEC + ICS/LABA therapy compared with ICS/LABA alone in symptomatic patients. These benefits also likely explain the improvements in exacerbation outcomes recently reported in 6- to 12-month trials comparing single-inhaler triple therapy with ICS/LABA alone in patients who were symptomatic and at increased risk of future exacerbations or with severe lung function impairment [19, 20].

The results in this study are similar to those reported in two recent analyses: a post hoc analysis of the TRILOGY study (NCT01917331) [20] which reported reduced risk of a composite CID with the addition of the LAMA glycopyrronium bromide to the ICS/LABA beclomethasone dipropionate/formoterol fumarate [34]; and the first prospective CID analysis in the FULFIL study (NCT02345161) [19], which reported a reduced risk of a composite CID and of all individual components (FEV1, SGRQ, and exacerbation CIDs) over 6 months with FF/UMEC/VI single-inhaler triple therapy compared with the ICS/LABA budesonide/formoterol (communication at the European Respiratory Society International Congress 2017, Naya et al. Poster PA3248). The inconsistency between the observed reduction in SGRQ CID events in the prospective analysis of the FULFIL study and the current analysis suggests that the 3-month CID assessment period in the current analysis may have been too short in duration to fully evaluate this component. Similarly, the recent IMPACT study (NCT02164513) showed a significantly reduced rate of moderate or severe COPD exacerbations, as well as improved lung function and SGRQ scores, following 52 weeks of once-daily FF/UMEC/VI single-inhaler triple therapy compared with the ICS/LABA FF/VI or the LAMA/LABA UMEC/VI in patients with COPD with a history of prior exacerbations [35]. The consistent improved stability observed for additional bronchodilation in all studies suggests a potential long-term benefit from improving lung function with two long-acting bronchodilators in symptomatic patients with COPD. Given that many patients fail to attain meaningful improvement in outcomes despite receiving pharmacological treatment, continued stability may be a useful treatment goal [21].

There has been increasing interest in the use of the CID concept as an additional efficacy endpoint. Indeed, the CID concept has been employed in several studies over the past two years to compare disease stability and freedom from deterioration between different combination therapies [21, 23, 34, 36, 37]. However, as this conceptual framework for assessing stability in COPD has only recently been developed, there is divergent methodology amongst different research groups regarding which components of deterioration should be included. The components included in this study (trough FEV1, SGRQ total score, and incidence of a moderate or severe exacerbation) were those included in the first study employing the CID endpoint [22], and have been widely adopted by other researchers [22, 36, 38]. The components were individually well-validated endpoints and were selected as they have been included in several long-term landmark trials [15, 16, 30, 31], thereby facilitating further analyses of the link between short-term CID assessment and increased future risks of mortality and severe exacerbations [32, 33]. Some follow-on studies have deviated from this CID approach to add a deterioration of ≥ 1 unit in the Transition Dyspnea Index focal score [23], hospitalized exacerbations and death [37, 38], or all components [34]. In some of these analyses, the original three-component CID definition was compared with these divergent definitions with no advantage being identified for the alternates [22, 38]. However, as assessing health status deterioration using the SGRQ component is impractical outside a clinical trial setting, replacing it with a health status deterioration measured using the simpler COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score has been shown to give very similar results [39]. The current set of CID components (lung function, health status [which can be measured by SGRQ or CAT score] and exacerbations) fully align with the aims stated in the GOLD report for short-term monitoring of a patient’s potential for future disease progression and assessing adequacy of current therapy [1]. Inclusion of hospitalizations and death in the CID definition may reduce the CID endpoint usefulness as a monitoring tool to predict these events, an essential aim of the endpoint. Nevertheless, refinement of the CID concept and further research is required to maximize the utility of this endpoint.

While bronchodilator therapy is the mainstay of treatment for symptomatic patients with COPD, the potential for an early short-term increase in the risk of non-fatal cardiovascular events in the first month after initiating any new LAMA or LABA bronchodilator treatment cannot be excluded [40]. In our integrated analysis, SAEs including cardiovascular events were numerically lower in patients receiving UMEC + ICS/LABA therapy than those receiving placebo + ICS/LABA. This highlights a likely favorable benefit:risk profile for additional bronchodilator therapy with UMEC, consistent with previous reports for UMEC therapy [24, 25, 41, 42].

A strength of this analysis is that it was based on four double-blind, placebo-controlled studies with robust replicate designs and high completion rates. In addition, the focus on all CID component events as well as the composite endpoint across multiple patient subgroups provides greater understanding of the utility of the composite CID endpoint overall. Potential limitations include the post hoc nature of the analysis, the fact that the GOLD classification used was based on the 2016 and not the 2018 report, and the short duration (12 weeks) of the trials, which may limit detection of differences between treatments in stability of SGRQ CID event, as previously discussed. In addition, the short duration of the trials prevented any analysis of the linkage between deterioration types. The 12-week treatment period also limited the number of patients likely to demonstrate a first exacerbation in all subgroups, especially as the populations enrolled were not enriched for a repeat exacerbation history on ICS/LABA therapy. Indeed only 7–9% of the 2016 GOLD Group D [29] patient subgroup satisfied this more stringent 2018 GOLD Group D criteria [1] based on exacerbation history only. The GOLD Group D subgroup analysis thereby focused predominantly on symptomatic patients with a FEV1 < 50% predicted. Nevertheless, this analysis detected a high overall incidence of instability in these symptomatic patients with severe COPD on ICS/LABA therapy in a short treatment period. Finally, the results of this analysis cannot contribute to an understanding of the role of add-on ICS therapy in preventing a CID. This is an important issue due to the increasing interest in the use of dual and triple combination therapies in symptomatic patients [36–39, 43, 44].

Conclusions

Addition of UMEC to ICS/LABA therapy in patients with COPD with moderate-to-severe breathlessness (mMRC scores ≥ 2) reduced the risk of a first CID of any type by 45–58% compared with continued ICS/LABA therapy. The early benefit of additional bronchodilation with UMEC was observed in all patient types analyzed, and was predominantly driven by stabilizing lung function and reducing exacerbation risk, with no detrimental change in the overall safety profile. These findings provide further rationale for the need to optimize bronchodilator therapy in patients remaining symptomatic on ICS/LABA therapy, and may provide insights on the need for more structured monitoring of disease stability in symptomatic patients with COPD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by GSK (Study Number: 202067). The funders of the study had a role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report and are also funding the article processing charges and open access fee. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance during development of the initial draft, assembling tables and figures, collating authors’ comments, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Elizabeth Jameson, PhD, and Meghan Betts, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript, and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Author Contributions

IPN and LT were involved in the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. DAL and CC were involved in the data analysis and interpretation.

Disclosures

Ian P. Naya is an employee of GSK and holds stocks and shares in GSK. David A. Lipson is an employee of GSK and holds stocks and shares in GSK. Chris Compton is an employee of GSK and holds stocks and shares in GSK. Lee Tombs is a contingent worker on assignment at GSK. ELLIPTA and DISKUS are owned by or licensed to the GSK group of companies.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. The study presented was an integrated post hoc analysis of four clinical trials all conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before participation in the studies considered in this analysis.

Data Availability

Data within this manuscript were presented at the European Respiratory Society International Conference 2015 (abstract: PA1487) and the American Thoracic Society International Conference 2017 (abstract: A3608). Anonymized individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from http://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital content

To view enhanced digital content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.6936044.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Updated 2018. http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf. Accessed Jan 23, 2018.

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) fact sheet. Updated November 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs315/en/. Accessed Nov 16, 2017.

- 3.Lopez-Campos JL, Tan W, Soriano JB. Global burden of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(1):14–23. 10.1111/resp.12660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins CR, Celli B, Anderson JA, et al. Seasonality and determinants of moderate and severe COPD exacerbations in the TORCH study. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(1):38–45. 10.1183/09031936.00194610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenkins CR, Postma DS, Anzueto AR, et al. Reliever salbutamol use as a measure of exacerbation risk in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:97. 10.1186/s12890-015-0077-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Punekar YS, Naya I, Small M, et al. Bronchodilator reliever use and its association with the economic and humanistic burden of COPD: a propensity-matched study. J Med Econ. 2017;20(1):28–36. 10.1080/13696998.2016.1223085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Punekar YS, Mullerova H, Small M, et al. Prevalence and burden of dyspnoea among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five European countries. Pulm Ther. 2016;2(1):59–72. 10.1007/s41030-016-0011-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Punekar YS, Sharma S, Pahwa A, Takyar J, Naya I, Jones PW. Rescue medication use as a patient-reported outcome in COPD: a systematic review and regression analysis. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):86. 10.1186/s12931-017-0566-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tashkin DP, Cooper CB. The role of long-acting bronchodilators in the management of stable COPD. Chest. 2004;125(1):249–59. 10.1378/chest.125.1.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cazzola M, Page C. Long-acting bronchodilators in COPD: where are we now and where are we going? Breathe. 2014;10(2):111–20. 10.1183/20734735.014813 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Short PM, Williamson PA, Elder DHJ, Lipworth SIW, Schembri S, Lipworth BJ. The impact of tiotropium on mortality and exacerbations when added to inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonist therapy in COPD. Chest. 2012;141(1):81–6. 10.1378/chest.11-0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simeone JC, Luthra R, Kaila S, et al. Initiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the US. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:73–83. 10.2147/COPD.S122013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozma CM, Paris AL, Plauschinat CA, Slaton T, Mackowiak JI. Comparison of resource use by COPD patients on inhaled therapies with long-acting bronchodilators: a database study. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:61. 10.1186/1471-2466-11-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee TA, Wilke C, Joo M, et al. Outcomes associated with tiotropium use in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1403–10. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1543–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):775–89. 10.1056/NEJMoa063070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frith PA, Thompson PJ, Ratnavadivel R, et al. Glycopyrronium once-daily significantly improves lung function and health status when combined with salmeterol/fluticasone in patients with COPD: the GLISTEN study, a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2015;70(6):519–27. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siler TM, Kerwin E, Tombs L, Fahy WA, Naya I. Triple therapy of umeclidinium + inhaled corticosteroids/long-acting beta2 agonists for patients with COPD: pooled results of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Pulm Ther. 2016;2:43–58. 10.1007/s41030-016-0012-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipson DA, Barnacle H, Birk R, et al. FULFIL trial: once-daily triple therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(4):438–46. 10.1164/rccm.201703-0449OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh D, Papi A, Corradi M, et al. Single inhaler triple therapy versus inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting beta2-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10048):963–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31354-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anzueto AR, Vogelmeier CF, Kostikas K, et al. The effect of indacaterol/glycopyrronium versus tiotropium or salmeterol/fluticasone on the prevention of clinically important deterioration in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1325–37. 10.2147/COPD.S133307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh D, Maleki-Yazdi MR, Tombs L, Iqbal A, Fahy WA, Naya I. Prevention of clinically important deteriorations in COPD with umeclidinium/vilanterol. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1413–24. 10.2147/COPD.S101612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh D, D’Urzo AD, Chuecos F, Munoz A, Garcia Gil E. Reduction in clinically important deterioration in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with aclidinium/formoterol. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):106. 10.1186/s12931-017-0583-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siler TM, Kerwin E, Singletary K, Brooks J, Church A. Efficacy and safety of umeclidinium added to fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in patients with COPD: results of two randomized, double-blind studies. Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;13(1):1–10. 10.3109/15412555.2015.1034256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siler TM, Kerwin E, Sousa AR, Donald A, Ali R, Church A. Efficacy and safety of umeclidinium added to fluticasone furoate/vilanterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results of two randomized studies. Respir Med. 2015;109(9):1155–63. 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.GSK. Incruse summary of product characteristics. Updated 2017. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/29394. Accessed Feb 2, 2018.

- 27.GSK. Highlights of prescribing information. Updated 2017. https://www.gsksource.com/pharma/content/dam/GlaxoSmithKline/US/en/Prescribing_Information/Incruse_Ellipta/pdf/INCRUSE-ELLIPTA-PI-PIL.PDF. Accessed Feb 2, 2018.

- 28.Celli BR, MacNee W, Force AET. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–46. 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Updated 2016. http://goldcopd.org/global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd-2016/. Accessed Nov 17, 2017.

- 30.Vestbo J. The TORCH (towards a revolution in COPD health) survival study protocol. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(2):206–10. 10.1183/09031936.04.00120603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vestbo J, Anderson W, Coxson HO, et al. Evaluation of COPD longitudinally to identify predictive surrogate end-points (ECLIPSE). Eur Respir J. 2008;31(4):869–73. 10.1183/09031936.00111707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naya I, Tombs L, Mullerova H, Compton C, Jones P. Long-term outcome following first clinically important deterioration in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(Suppl 60):PA304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabe KF, Halpin D, Martinez F, et al. Predicting long-term outcomes and future deterioration in COPD with a composite endpoint: post hoc analysis of the UPLIFT study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A2717. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh D, Papi A, Vezzoli S, et al. CHF5993 pMDI (extrafine Beclometasone Dipropionate:BDP, Formoterol Fumarate:FF, Glycopyrronium Bromide:GB) reduces clinically important deteriorations (CID) in COPD: post hoc analysis of TRILOGY study. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(Suppl 61):PA533. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N, et al. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1671–80. 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anzueto AR, Kostikas K, Shen S, et al. Indacaterol/glycopyrronium reduces the risk of clinically important deterioration versus salmeterol/fluticasone: the FLAME study. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(Suppl 61):PA3255. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh D, Papi A, Vezzoli S, et al. Effect of CHF5993 pMDI (extrafine Beclometasone Dipropionate:BDP, Formoterol Fumarate:FF, Glycopyrronium Bromide:GB) on clinically important deteriorations (CID) in COPD: post hoc analysis of TRINITY study. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(Suppl 61):PA3949. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buhl R, McGarvey L, Korn S, et al. Benefits of tiotropium + olodaterol over tiotropium at delaying clinically significant events in patients with COPD classified as GOLD B. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A6779. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naya I, Barnacle H, Birk R, et al. Clinically important deterioration in advanced COPD patients using single inhaler triple therapy: results from the FULFIL study. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(Suppl 61):PA3248. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang MT, Liou JT, Lin CW, et al. Association of cardiovascular risk with inhaled long-acting bronchodilators in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a nested case-control study. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):229–38. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feldman G, Maltais F, Khindri S, et al. A randomized, blinded study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of umeclidinium 62.5 mug compared with tiotropium 18 mug in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:719–30. 10.2147/COPD.S102494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manickam R, Asija A, Aronow WS. Umeclidinium for treating COPD: an evaluation of pharmacologic properties, safety and clinical use. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(11):1555–61. 10.1517/14740338.2014.968550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sion KYJ, Huisman EL, Punekar YS, Naya I, Ismaila A. A network meta-analysis of long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) and long-acting b2-agonist (LABA) combinations in COPD. Pulm Ther. 2017;3(2):297–316. 10.1007/s41030-017-0048-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papi A, Vestbo J, Fabbri L, et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1076–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30206-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data within this manuscript were presented at the European Respiratory Society International Conference 2015 (abstract: PA1487) and the American Thoracic Society International Conference 2017 (abstract: A3608). Anonymized individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from http://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.