Abstract

Introduction

nab-Paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (nab-P + G) and FOLFIRINOX (FFX) are among the most common first-line (1L) therapies for metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (MPAC), but real-world data on their comparative effectiveness are limited.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study compared the efficacy and safety of 1L nab-P + G versus FFX, overall and under specific treatment sequences. Medical records were reviewed by 215 US physicians who provided information on MPAC patients who initiated 1L therapy with nab-P + G or FFX between April 1, 2015 and December 31, 2015. Study outcomes were overall survival (OS) and tolerability. OS was compared using Kaplan–Meier curves and adjusted Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

In total, 654 medical records were reviewed, including those of 337 and 317 patients initiated on nab-P + G and FFX as 1L MPAC therapy, respectively. nab-P + G-initiated patients were older, less likely to have ECOG ≤ 1, and had more comorbidities than FFX-initiated patients. Median OS (mOS) was 12.1 and 13.8 months for nab-P + G- and FFX-initiated patients, respectively (HR = 0.99, P = 0.96). Among patients with ECOG ≤ 1, mOS was 14.1 and 13.7 months, respectively (HR = 1.00, P = 0.99). Among patients with 1L nab-P + G and FFX, 36.1% and 41.3% received 2L therapy and experienced mOS of 16.3 and 16.6 months, respectively (HR = 1.04, P = 0.76). The rates of diarrhea, fatigue, mucositis, and nausea and vomiting were significantly higher in the FFX than nab-P + G cohort.

Conclusion

The real-world survival was similar between patients receiving 1L nab-P + G or FFX both overall and among patients who received active 2L treatments. In addition, nab-P + G was associated with significantly lower rates of common AEs compared with FFX.

Funding

Celgene.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-018-0784-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adverse events, FOLFIRINOX, Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, nab-Paclitaxel, Real-world evidence, Survival analysis

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in both men and women in the USA [1–3]. Despite dramatic therapeutic improvements, the prognosis of PC remains poor [4]. Standard treatments include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, chemoradiation, and targeted therapy [2, 3]. Surgical excision is highly effective, but is not suitable for 80–85% of patients because PC is typically detected after it has spread to lymph nodes or distant organs [2]. About 60% of PC patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, with a median life expectancy of around 1 year with current treatments [5–7].

Current treatment options for metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (MPAC) often involve monotherapy or combination therapies with active agents such as gemcitabine, nab-P, erlotinib, capecitabine, cisplatin, leucovorin, fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin, and irinotecan [3]. Gemcitabine monotherapy was established as a standard of care in 1997 for metastatic PC after demonstrating greater clinical benefit over 5-FU therapy [2, 8]. In 2011, the ACCORD trial showed that the FFX regimen (5-FU + leucovorin + irinotecan + oxaliplatin) was superior to gemcitabine alone in terms of efficacy [median overall survival (OS) of 11.1 (FFX) and 6.8 months (gemcitabine)] although it was also associated with increased toxicity [9]. The combination of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (nab-P + G) was approved for the first-line (1L) treatment of patients with MPAC in 2013 on the basis of results from the MPACT trial [10, 11]. This combination was shown to lengthen survival (median OS of 8.5 months in the nab-P + G group vs. 6.7 months in the gemcitabine alone group) and delay the disease spread.

The choice of 1L chemotherapy for MPAC is influenced by the patient’s overall health [e.g., Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status] and risk of adverse events. Current guidelines recommend nab-P + G for patients with ECOG ≤ 2 [or Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥ 70] and low bilirubin levels, and FFX for patients with ECOG ≤ 1 and low bilirubin levels [2, 3]. Other options for 1L treatment for patients with good performance status include gemcitabine-based combination therapy and fluoropyrimidine/leucovorin/oxaliplatin [3].

When the initial chemotherapy regimen ceases to control cancer growth or if patients experience toxicities, patients may benefit from second-line (2L) chemotherapy. For example, a patient who started treatment with nab-P + G may switch to FFX, or a related regimen, as 2L therapy, and vice versa [3]. In 2015, the FDA approved nanoliposomal irinotecan (nal-IRI) as the first drug specifically indicated for use as 2L treatment for PC [12]. Among patients who had previously received a chemotherapy regimen containing gemcitabine, nal-IRI improved survival when given in combination with 5-FU and leucovorin (patients treated with nal-IRI/5-FU/leucovorin had a median OS of 6.1 months vs. 4.2 months for 5-FU/leucovorin only) [13].

Though the aforementioned randomized controlled trials led to the approval of new treatments for MPAC, there has been no head-to-head trial comparing these new treatments to one another. Particularly, there is as yet no head-to-head trial comparing nab-P + G versus FFX in the 1L setting, and there are some important limitations to their comparative evidence in real-world settings. A recent indirect comparison study found that FFX was associated with improved OS compared to nab-P + G, and had a comparable safety profile, suggesting FFX as the more cost-effective option for 1L therapy [14]. A Bayesian mixed treatment comparison similarly found an 83% probability that FFX was the best regimen versus 11% for nab-P + G, with OS hazard ratio (HR) favoring FFX versus nab-P + G (although not statistically significant), and no obvious difference in toxicities [15]. Another recent indirect comparison of the efficacy and safety of these two regimens found, however, that the OS for nab-P + G was larger than that of FFX, although the survival benefit was not statistically significant [16]. Incorporating cost rendered nab-P + G as the economical choice of both regimens. Moreover, two recent retrospective studies concluded that the median OS values in MPAC patients treated with 1L nab-P + G or FFX were not statistically different [17, 18]. With these conflicting results, the indirect comparative evidence for nab-P + G and FFX as 1L therapies for MPAC may be viewed as inconclusive.

With the advent of additional treatment options, such as nal-IRI in the 2L setting following 1L gemcitabine-based regimens, there is an increasing need to understand changes in treatment patterns and real-world comparative effectiveness across all lines of therapy in MPAC. The present study follows a retrospective cohort design and collects recent real-world data from USA medical records to (i) describe treatment patterns for patients who initiated MPAC treatment with 1L nab-P + G or FFX and potentially sequenced to 2L regimens and (ii) compare OS outcomes associated with different treatment sequences.

Methods

Study Design

This study used a retrospective cohort design, with data collected from medical records, to represent clinical practice, i.e., care was not driven by a study protocol.

Physician Recruitment

Oncologists were recruited from a nationwide panel of physicians with verified credentials who had pre-registered to be invited for participation in retrospective chart reviews. This address-based panel was maintained by Schlesinger Associates. To support the objectivity of patient sampling and data entry, participating physicians were not informed of the research objectives or the identity of the study sponsor. Physicians were instructed to identify all charts meeting the selection criteria and to randomly select up to five of those charts for data extraction. Physicians were characterized in terms of their geographic location, medical specialty, and practice setting.

Patient Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: diagnosed with MPAC; initiated on any 1L regimen for MPAC among nab-P + G and FFX from April 1, 2015 to December 31, 2015 (i.e., the index window); aged at least 18 years at 1L therapy initiation; under the care of a participating physician for MPAC treatment at 1L therapy initiation; medical records were available for review from the initiation of 1L therapy until the most recent follow-up visit with the physician or death. Exclusion criteria included the use of other chemotherapy regimens for PC tumor control on the date of 1L treatment initiation (aside from nab-P + G or FFX; bone-targeted agents, treatments to manage symptoms and/or adverse events were allowed), and enrollment in a protocol-driven clinical study at the time of first-line therapy initiation. The index window was designed to ensure (1) patients had a minimum follow-up time of 9 months (based on the median OS of 1L nab-P + G) after initiation of 1L treatment, (2) patients had the opportunity to receive nal-IRI in the 2L setting after its FDA approval, and (3) timely data collection and reporting.

Data for included patients were extracted by the participating physicians and entered into a secure electronic case report form (eCRF). The eCRF was designed by all study authors and included extensive real-time error checking for the ranges of collected variables and temporal sequences of events. Responses of “unknown/missing” were allowed. The eCRF was pilot tested with two oncologists to ensure patient selection criteria and requested data elements were clearly described. Data collected in the eCRF were personally non-identifiable. The eCRF and study synopsis were reviewed by the New England Institutional Review Board, which granted exemption from a full review for this retrospective and non-interventional study of non-identifiable data.

Sample Selection

Patients were categorized into two study cohorts: (1) patients who initiated nab-P + G as 1L therapy, (2) patients who initiated FFX as 1L therapy. This study employed a sequential approach to data collection, with two waves of patients obtained from two waves of invitations sent to non-overlapping sets of physicians. Patients in wave 1 (34.1% of the entire sample) were used to estimate the real-world frequencies of different treatment sequences, including nab-P + G or FFX followed by an active 2L treatment, hospice and supportive care only, or no 2L treatment. All patients in wave 2, however, received an active 2L treatment in order to increase the sample size of patients with an active 2L treatment and better assess the types of therapy and associated survival outcome in patients who received more than one line of chemotherapy. The proportions of patients following different treatment sequences in wave 1 were used to construct sampling weights to adjust for the oversampling of patients with an active 2L treatment imposed in wave 2. Statistical analyses incorporated these weights to estimate the true real-world distribution of treatment sequences and outcomes.

The main outcome of interest was OS, defined as the time from initiation of the 1L therapy to death from any cause. Patients’ baseline characteristics, assessed prior to the initiation of 1L therapy, included demographics, comorbidities, metastatic sites, performance status, laboratory measures, and prior PC treatment, with the complete list provided in Table 1. Tolerability outcomes and treatment patterns were also collected.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by first-line therapy group

| Total | 1L therapy | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 654 | nab-P + G | FFX | ||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at 1L therapy initiation (years) | 61.99 ± 9.63 | 64.59 ± 9.02 | 59.03 ± 9.46 | < 0.001* |

| Female | 34.12% | 35.30% | 32.78% | 0.64 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.38 | |||

| Asian | 3.21% | 4.60% | 1.62% | |

| Black or African American | 21.59% | 21.92% | 21.21% | |

| Hispanic | 5.83% | 6.28% | 5.31% | |

| White | 68.26% | 66.65% | 70.10% | |

| Other/unknown | 1.12% | 0.56% | 1.76% | |

| Diagnosis characteristics | ||||

| Metastatic at diagnosis | 92.99% | 93.47% | 92.44% | 0.67 |

| Duration of MPAC at 1L therapy initiation (months) | 1.59 ± 9.20 | 1.49 ± 6.75 | 1.70 ± 11.39 | 0.7 |

| Site of metastases | ||||

| Number of metastatic locations | 2.02 ± 0.98 | 2.02 ± 0.96 | 2.03 ± 1.00 | 0.88 |

| Liver | 75.52% | 75.34% | 75.73% | 0.93 |

| Lymph nodes | 44.96% | 45.07% | 44.84% | 0.97 |

| Lungs | 32.28% | 33.52% | 30.86% | 0.61 |

| Peritoneum | 22.55% | 21.91% | 23.29% | 0.77 |

| Bones | 13.44% | 12.13% | 14.94% | 0.47 |

| Adrenal glands | 12.77% | 12.70% | 12.85% | 0.97 |

| Location of tumor in pancreas | ||||

| Head | 50.85% | 50.46% | 51.30% | 0.88 |

| Center | 26.96% | 27.48% | 26.37% | 0.82 |

| Tail | 23.90% | 24.44% | 23.29% | 0.82 |

| Unknown location | 4.63% | 2.79% | 6.75% | 0.09 |

| Previous therapy for PC prior to MPAC among patients initially diagnosed with non-metastatic diseasea | ||||

| No prior therapy for PC | 74.46% | 65.91% | 82.91% | 0.18 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy for PC | 9.55% | 12.73% | 6.41% | 0.34 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for PC | 4.28% | 2.12% | 6.41% | 0.32 |

| Radiation for PC | 7.45% | 15.00% | 0.00% | 0.17 |

| Surgery for PC | 4.28% | 2.12% | 6.41% | 0.32 |

| Previous therapy for MPAC prior to 1L treatmentb | ||||

| No prior therapy | 93.51% | 91.51% | 95.81% | < 0.05* |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.74% | 0.97% | 0.48% | 0.31 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.30% | 0.42% | 0.16% | 0.4 |

| Radiation | 1.20% | 1.96% | 0.32% | < 0.05* |

| Surgery | 3.51% | 4.33% | 2.58% | 0.36 |

| Other/unknown prior treatment | 1.27% | 0.48% | 1.95% | < 0.05* |

| Performance score at 1L therapy initiation | ||||

| ECOG | < 0.001* | |||

| Score 0 | 16.37% | 7.09% | 26.98% | |

| Score 1 | 63.80% | 63.20% | 64.48% | |

| Score 2 | 18.73% | 27.91% | 8.21% | |

| Score 3–4 | 1.11% | 1.80% | 0.32% | |

| Number of comorbiditiesc | 1.50 ± 1.62 | 1.22 ± 1.48 | 1.74 ± 1.69 | < 0.01* |

FFX FOLFIRINOX, nab-P + G nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel/gemcitabine, 1L first-line

*P < 0.05

aRefers to the treatments received before diagnosis of MPAC

bRefers to the treatments received after diagnosis of MPAC but before 1L treatment initiation

cThe comorbidities considered in this study were cerebrovascular diseases, peripheral neuropathy, anemia, hematologic diseases, neutropenia, bile duct stent, biliary obstruction, chronic pancreatitis, gastrointestinal disorder, ulcer disease, cardiovascular disorder, hepatic disorder, pulmonary disease, renal disorder, other malignancies, diabetes mellitus, prediabetes or glucose intolerance, obesity, and current or former smoker

Statistical Analyses

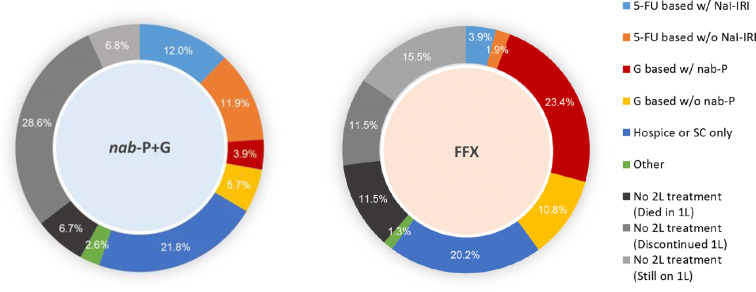

A chart describing the percentages of patients following each possible two-line treatment sequence was presented, which incorporated sampling weights derived from wave 1 and the sampling scheme imposed in wave 2 to recover the true real-world distribution of treatment sequences.

Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables; counts and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Baseline characteristics were compared between study cohorts using weighted ANOVA for continuous variables and weighted chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Unadjusted comparisons of time-to-event outcomes between study cohorts were summarized using survival curves, with times to event censored at last contact. Analyses were stratified using groups defined by treatments received in 1L and treatment sequence settings, consistent with the groups used to stratify summaries of baseline characteristics. The survival curves corresponding to the 1L therapy and by treatment sequence were based on weighted Nelson–Aalen estimator and Kaplan–Meier estimator, respectively (because all patients in the sequencing analyses received an active 2L therapy, the outcomes associated with these sequences did not need to be adjusted with the sampling weights). Statistical comparisons were based on log-rank tests. Adjusted comparisons were based on multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, with adjustment for baseline characteristics, including age at 1L therapy initiation, gender, number of comorbidities, number of metastatic locations, duration of MPAC at 1L therapy initiation, and ECOG score, which have been identified as important prognostic factors for outcomes in MPAC [19, 20]. A subgroup analysis of OS was conducted among patients with active 2L treatment. Patients with missing baseline values were excluded from analyses. The proportional hazards assumption was tested for these models. All analyses were conducted using R Version 3.3. A two-tailed α level of 0.05 was used to assess statistical significance.

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. We would also like to thank the participants of the study.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 215 physicians contributed chart data, representing the Mid-West (20.5%), North-East (26.5%), South (30.2%), and West (22.8%) of the USA. The majority (69.3%) were in community practice as opposed to academic practice.

Charts were reviewed for 654 patients receiving either nab-P + G or FFX as 1L therapy for MPAC. Patient baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The average age was 62 years with an average follow-up time of 10.7 months. On average, patients who started on 1L nab-P + G were older and less healthy than patients started on 1L FFX, with nab-P + G patients presenting worse performance status, higher bilirubin levels, larger number of comorbidities, and higher proportions of diabetes, ulcers, cerebrovascular, and pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases.

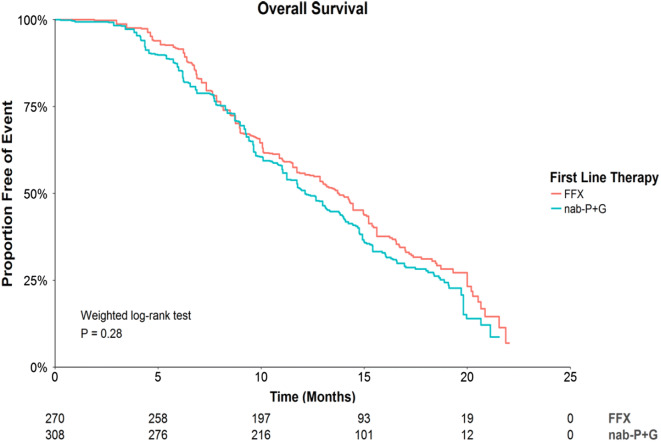

Overall Survival in First-Line Treatment

During the follow-up period, death occurred in 58.5% and 51.8% of patients who used nab-P + G and FFX, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, there were no statistically significant OS differences among treatment groups (Fig. 1), with an HR of 0.86, P = 0.28 for FFX versus nab-P + G. This result was supported by adjusted analyses (HR = 0.99, P = 0.96) presented in Table 2. Median durations of OS were 12.1 and 13.8 months following initiation of 1L nab-P + G and FFX.

Fig. 1.

Survival curves for OS by 1L therapy. nab-P + G, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel/gemcitabine; FFX FOLFIRINOX, 1L first-line

Table 2.

Adjusted analysis for OS in first-line therapy and in treatment sequences

| Effect | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| In 1L therapy | |||

| 1L therapy FFX vs. nab-P + G | 0.99 | (0.74, 1.34) | 0.96 |

| Age at therapy initiation (years) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.02) | 0.57 |

| Gender male vs. female | 1.17 | (0.85, 1.61) | 0.33 |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.16 | (1.06, 1.28) | < 0.01* |

| Number of metastatic locations | 1.23 | (1.04, 1.44) | < 0.05* |

| Duration of MPAC at therapy initiation (months) | 0.99 | (0.99, 1.00) | 0.15 |

| ECOG vs. score 0 | |||

| Score 1 | 1.17 | (0.77, 1.78) | 0.45 |

| Score 2 | 1.44 | (0.87, 2.37) | 0.16 |

| Score 3–4 | 1.19 | (0.51, 2.78) | 0.68 |

| In treatment sequences | |||

| Treatment sequence (active 2L) FFX → active 2L vs. nab-P + G → active 2L | 1.04 | (0.79, 1.37) | 0.76 |

| Age at therapy initiation (years) | 1.02 | (1.00, 1.03) | < 0.01* |

| Gender male vs. female | 1.15 | (0.86, 1.54) | 0.34 |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.97 | (0.88, 1.07) | 0.54 |

| Number of metastatic locations | 1.23 | (1.07, 1.41) | < 0.01* |

| Duration of MPAC at therapy initiation (months) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | 0.97 |

| ECOG vs. score 0 | |||

| Score 1 | 1.39 | (0.93, 2.08) | 0.11 |

| Score 2 | 1.29 | (0.79, 2.12) | 0.31 |

| Score 3–4 | 2.92 | (1.42, 6.00) | < 0.01* |

CI confidence interval, 1L first-line, 2L second-line, nab-P + G nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel/gemcitabine, FFX FOLFIRINOX, MPAC metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

*P < 0.05

Comparing nab-P + G and FFX among the subgroup of patients with ECOG ≤ 1 also revealed no significant differences in OS (unadjusted HR = 1.04, P = 0.81, for FFX vs. nab-P + G), with median durations of OS of 14.1 and 13.7 months following initiation of 1L nab-P + G and FFX, respectively (see Supplementary Material).

Adverse Events

Patients with 1L nab-P + G and FFX have different tolerability profiles in terms of the frequencies of the most common events and conditions recorded in medical records between these two groups (Table 3). For instance, diarrhea, stomatitis, fatigue, mucositis, and nausea and vomiting are significantly more frequent in the FFX than nab-P + G group. The incidence of any-grade adverse events (AEs) was not significantly different among patients who received 1L nab-P + G or FFX (35.0% vs. 33.6%, respectively; P = 0.79; Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of most common adverse events (> 10% of total cases) by first-line therapy group

| Total | 1L therapy | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 654 (%) | nab-P + G (%) | FFX (%) | ||

| Anemia | 45.43 | 45.50 | 45.34 | 0.98 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 12.49 | 9.21 | 16.23 | 0.07 |

| Neutropenia | 32.73 | 33.38 | 31.99 | 0.79 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 24.97 | 27.11 | 22.52 | 0.34 |

| Diarrhea | 29.46 | 20.51 | 39.71 | < 0.001* |

| Stomatitis | 10.10 | 3.62 | 17.52 | < 0.001* |

| Abdominal pain | 19.48 | 21.18 | 17.54 | 0.38 |

| Alopecia | 16.45 | 16.34 | 16.57 | 0.96 |

| Decreased appetite | 27.79 | 25.81 | 30.06 | 0.39 |

| Dehydration | 18.54 | 14.93 | 22.67 | 0.08 |

| Fatigue | 37.28 | 31.80 | 43.56 | < 0.05* |

| Mucositis | 11.37 | 5.16 | 18.48 | < 0.001* |

| Nausea and vomiting | 23.25 | 18.27 | 28.94 | < 0.05* |

FFX FOLFIRINOX, nab-P + G nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel/gemcitabine, 1L first-line

*P < 0.05

Sequencing Outcomes

Figure 2 shows the treatment sequences corresponding to patients starting on either nab-P + G or FFX as 1L therapy for MPAC. The corresponding percentages incorporate sampling weights derived from wave 1 and the sampling scheme imposed in wave 2 to recover the true real-world distribution of treatment sequences. Among patients who received 1L nab-P + G, 36.1% received an active 2L therapy (i.e., therapies other than hospice and supportive care only) and 23.9% received a 5-FU-based 2L therapy (with half of these patients receiving 5-FU + nal-IRI). Among those who received 1L FFX, 41.3% received an active 2L therapy and 34.2% received a gemcitabine-based 2L therapy.

Fig. 2.

Treatment sequences. The inner cycle depicts the 1L treatment; the outer cycle depicts the 2L treatment. nab-P + G, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel/gemcitabine; FFX, FOLFIRINOX; 5-FU based w/Nal-IRI, fluorouracil (5-FU) based regimen with nanoliposomal irinotecan; 5-FU based w/o Nal-IRI, fluorouracil (5-FU) based regimen without nanoliposomal irinotecan; G based w/ABR, gemcitabine-based regimen with nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel; G based w/o ABR, gemcitabine-based regimen without nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel; Hospice or SC only, hospice or supportive care only; Other, other drug (active) treatment; 1L, first-line

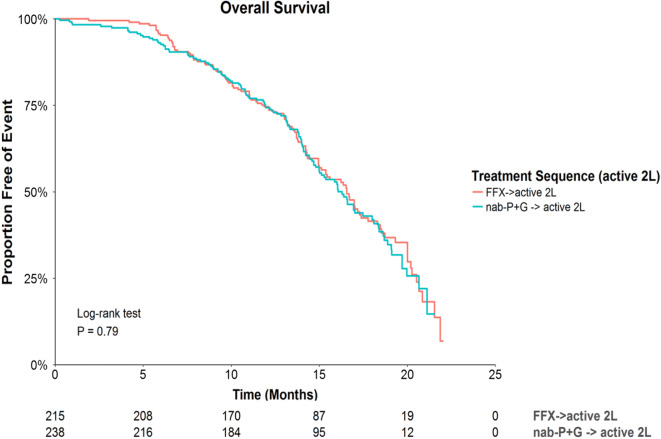

Among those who initiated an active 2L therapy, there were no statistically significant differences in OS based on the unadjusted analyses (HR = 0.97, P = 0.79 for FFX vs. nab-P + G followed by active 2L therapy; Fig. 3). Similarly, the adjusted analyses suggested no significant difference among these groups (HR = 1.04, P = 0.76; Table 2). The median OS was 16.3 and 16.6 months following initiation of 1L nab-P + G and FFX, respectively. The median time to next therapy for patients who received nab-P + G followed by an active therapy was 8.6 months, and 8.0 months for patients who received FFX followed by an active 2L therapy (log-rank P = 0.11).

Fig. 3.

Survival curves for OS by treatment sequence. nab-P + G, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel/gemcitabine; FFX FOLFIRINOX, 2L second-line

Comparing sequencing outcomes of nab-P + G and FFX followed by any active 2L among the subgroup of patients with ECOG ≤ 1 demonstrated no significant differences in OS (HR = 1.13, P = 0.42, for FFX vs. nab-P + G), with median durations of OS of 16.6 and 16.5 months following initiation of 1L nab-P + G and FFX, respectively. Patients who initiated an active 2L therapy were further stratified into four cohorts: (1) nab-P + G followed by 5-FU + nal-IRI (N = 85), (2) nab-P + G followed by another active 2L (N = 153), (3) FFX followed by gemcitabine-based therapy + nab-P (N = 136), and (4) FFX followed by another active 2L (N = 79). The median OS was 16.0, 16.4, 16.6, and 17.00 months for the four cohorts, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in OS among these four cohorts in either the unadjusted or the adjusted analyses.

Discussion

Real-world data on the effectiveness of and treatment patterns associated with nab-P + G versus FFX for 1L MPAC have been limited. The current retrospective cohort study compared the effectiveness of 1L nab-P + G versus FFX overall and under specific treatment sequences for MPAC. Charts were reviewed from a large number of physicians across the USA, representing both community practice and academic-affiliated practice settings. Across multiple comparative analyses, no significant differences were observed in OS between patients who were initiated on nab-P + G versus FFX. Similar results were obtained in subgroup analyses focusing on patients with ECOG ≤ 1. Among those who initiated an active 2L therapy, there were no statistically significant differences in OS between patients who received nab-P + G or FFX as 1L therapy. When stratifying the analyses by the type of 2L therapy, the differences remained insignificant. These results are in line with two recent retrospective studies that found no statistically significant difference in the median OS of MPAC patients treated with 1L nab-P + G or FFX [17, 18]. In addition to conducting subgroup survival analyses among patients with ECOG ≤ 1, in the Supplementary Material we also present several subgroup analyses, including subgroup analyses for patients who did not receive adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy for PC, patients who had metastatic disease at diagnosis, patients who were treated within academic institutions, and patients who were treated in community institutions. In line with the results in the overall population, all of these analyses consistently indicated that OS was similar in the nab-P + G and FFX 1L cohorts.

Taken together, these findings provide evidence of similar real-world effectiveness, in terms of OS, for nab-P + G and FFX as 1L therapies for MPAC. To our knowledge, the present study represents the first real-world comparison of these therapies in a broad and representative sample of oncology practices. Previous studies based on indirect comparisons of clinical trials have also not yielded conclusive evidence of differences in efficacy between these treatments [14–16].

The median OS values for 1L nab-P + G and FFX in this study were larger than the ones observed in the nab-P + G and FFX pivotal trials [9, 11] (by approximately 3.6 and 2.7 months, respectively), and also larger than results from other real-world studies, although to a lesser extent [17, 18, 21, 22]. These longer durations could be due to differences in patient populations between the current study and those in the clinical trials. For example, the racial composition in this study reflects the USA population and is similar to the one in the Von Hoff et al. study [11] but may differ from that in the Conroy et al. study [9] which was conducted in France. Additionally, the inclusion criteria in these trials were more stringent than those in the current study. The Von Hoff et al. study [11] only included patients with ECOG ≤ 2, adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function, and no previous chemotherapy for MPAC, while the Conroy et al. study [9] only included patients younger than 75 years, with ECOG ≤ 1, and adequate platelet count and renal function. These criteria might have resulted in the inclusion of a healthier and more homogenous population of patients in the clinical trials than the one in this study. Moreover, differences in treatment patterns (dosing and frequency) and/or improved supportive care over time in the real-world versus clinical trial settings might also help explain the longer survival times in this study.

Consistent with a recent retrospective study [16] and previous clinical trials [9, 11], the frequencies of the most commonly reported AEs were higher among patients with 1L FFX than those with nab-P + G. The frequency of neutropenia in our study was not statistically different among the two 1L cohorts.

Among patients who received an active 2L therapy, two-thirds of those who were initiated on nab-P + G received a 5-FU-based 2L regimen, whereas a larger majority (82.8%) of those that were initiated on FFX received a gemcitabine-based 2L regimen, with most of the remainder receiving 5-FU + nal-IRI. These sequencing results are roughly in line with NCCN guidelines [3], which recommend 5-FU-based therapy (or radiation therapy) as 2L for those previously treated with gemcitabine-based therapy, whereas, if previously treated with 5-FU-based therapy, the recommended 2L therapies include gemcitabine-based therapy, 5-FU + nal-IRI, or radiation therapy. In contrast with guidelines, however, about one quarter of the patients initiated on nab-P + G received a gemcitabine-based 2L therapy.

The current study design has a number of strengths, including the use of real-world data that complements the evidence from clinical trials, as patients in randomized controlled trials do not always reflect real-world populations. The charts in this study are from a nationally representative sample of physicians from both community and academic practice. Moreover, the current design captured a more diverse study population than clinical trials studying similar therapies because of less restrictive patient selection criteria.

As a retrospective study of non-randomized treatment assignments, this study is subject to important limitations. Firstly, comparisons of outcomes associated with different treatments may be confounded by measured or unmeasured pre-treatment differences between groups. In addition, there may be biases due to retrospective, as opposed to prospective, sampling (e.g., selection bias, recall bias, and non-random missing data). However, we expect that any effects these biases may have on the survival data would affect both 1L treatment cohorts in a similar way, such that the estimated comparative effectiveness (measured by the OS hazard ratios) is in fact valid. Nonetheless, the present study design aimed to mitigate these limitations by adjusting for multiple prognostic factors in the comparative analyses, and by using a randomization algorithm for physicians to sample eligible patients. In this study we did not evaluate information regarding the dosing schedule of the different regimes, which would be an important topic for future analyses. The recording of AEs in charts may be heterogeneous across practices, and less standardized than in a clinical trial setting. However, we think that presenting these data is valuable, as it provides insights into the safety profiles of these regimens in real-world settings, and enables a more balanced view of the comparison between nab-P + G and FFX that considers both efficacy and safety endpoints. Moreover, any bias in the recording of AEs by physicians is likely to impact both cohorts similarly. In addition, the comparative frequencies of the most commonly reported AEs in the current study are consistent with the data reported in the pivotal clinical trials [9, 11].

Conclusion

Using a nationwide sample of MPAC patients, we observed that those receiving either nab-P + G or FFX as 1L therapy exhibited similar real-world outcomes in terms of OS. Similar outcomes following these 1L treatments were also observed within the subpopulation of patients who went on to receive active 2L treatments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by Celgene. Celgene is also funding the journal’s Open Access fee. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Prior Presentation

A synopsis of the content of this study has been presented in poster format at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2018 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium, held from January 18, 2018 to January 20, 2018 in San Francisco, CA, USA.

Disclosures

Sunnie Kim has received consultancy fees from Celgene. John L. Marshall has received consultancy fees from Celgene. James E. Signorovitch is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. Hongbo Yang is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. Oscar Patterson-Lomba is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. Cheryl Q. Xiang is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. Analysis Group, Inc. has received consultancy fees from Celgene. Brian Ung is a Celgene employee. Monika Parisi is a Celgene employee.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.7028858.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2017. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2017.html. Accessed July 2017.

- 2.Ducreux M, Caramella C, Hollebecque A, et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:v56–68. 10.1093/annonc/mdv295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15:1028–61. 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aprile G, Negri FV, Giuliani F, et al. Second-line chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer: which is the best option? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;115:1–12. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CancerWorld. Management of metastatic pancreatic cancer: current strategies and future directions. http://cancerworld.net/e-grandround/management-of-metastatic-pancreatic-cancer-current-strategies-and-future-directions/. Accessed July 2017.

- 6.Sohal DP, Mangu PB, Khorana AA, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2784–96. 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfgang CL, Herman JM, Laheru DA, et al. Recent progress in pancreatic cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:318–48. 10.3322/caac.21190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer.Net. Pancreatic cancer: treatment options. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/pancreatic-cancer/treatment-options. Accessed June 2018.

- 9.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). ABRAXANE prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021660s037lbl.pdf. Accessed November 2017.

- 11.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–703. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ur Rehman SS, Lim K, Wang-Gillam A. Nanoliposomal irinotecan plus fluorouracil and folinic acid: a new treatment option in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16:485–92. 10.1080/14737140.2016.1174581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang-Gillam A, Li C-P, Bodoky G, et al. Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:545–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00986-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollmann S, Alloul K, Attard C, Kavan P. PD-0018 An indirect treatment comparison and cost effectiveness analysis comparing FOLFIRINOX with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:ii11–2 (Abstract). 10.1093/annonc/mdu164.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan K, Shah K, Lien K, et al. A Bayesian meta-analysis of multiple treatment comparisons of systemic regimens for advanced pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108749. 10.1371/journal.pone.0108749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gharaibeh M, McBride A, Bootman JL, Cranmer LD, Abraham I. Economic evaluation for the United States (US) of gemcitabine (GEM), nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (NAB-P+GEM), and FOLFIRINOX as first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC). J Med Econ 2015;33:6605. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cartwright TH, Parisi M, Espirito JL, et al. Treatment outcomes with first-line (1L) nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine (AG) and FOLFIRINOX (FFX) in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (mPAC). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:e18147. 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e18147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braiteh F, Patel MB, Parisi M, et al. Comparative effectiveness and resource utilization of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine for the first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a US community setting. Cancer Manag Res. 2017;9:141. 10.2147/CMAR.S126073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilici A. Prognostic factors related with survival in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10802–12. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tas F, Sen F, Keskin S, Kilic L, Yildiz I. Prognostic factors in metastatic pancreatic cancer: older patients are associated with reduced overall survival. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:788–92. 10.3892/mco.2013.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Chen L, Camateros P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of FOLFIRINOX or nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a population-based analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:6561. 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.6561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel L, Hollmann S, Attard C, Maroun J. Real-world experience with FOLFIRINOX: a review of Canadian and international registries. Oncol Exch. 2014;13:18–23. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited.