Abstract

Online instruction has become increasingly a commonplace in higher education, broadly and within the field of behavior analysis. Given the increased availability of online instruction, it is important to establish how learning outcomes are influenced by various teaching methods, in order to effectively train the next generation of behavior analysts. This study used a between-group design to evaluate the use of asynchronous online class discussion. Results indicate greater group mean performance on quizzes for students who were required to participate in asynchronous discussion as a component of instruction.

Demonstration of the effectiveness of a typical component of online instruction

Procedures can be used to evaluate instructional methods in behavior analytic coursework

Asynchronous online discussion is a promising component of online coursework

Active learning pedagogy is more effective when compared with passive learning pedagogy

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40617-016-0157-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Teaching behavior analysis, Online learning, Asynchronous discussion, Active learning

Students who seek post-secondary education in behavior analysis can find coursework that is delivered using a variety of methods, including traditional face-to-face lecture series and online and hybrid courses. The traditional classroom is no longer a barrier for those who seek higher education; over 30% of college students take at least one online course during their academic career (Driscoll, Jicha, Hunt, Tichavsky, & Thompson, 2012). The field of behavior analysis seems to be more progressive than the average reported above, meaning that many students of behavior analysis, and those charged with imparting knowledge to them, are studying and delivering instruction using some kind of online platform. According to the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) listing of approved course sequences toward BACB eligibility requirements at the master’s and bachelor’s level, located in the USA, there are a total of 210 university training programs; 71 of the above programs are listed as distance education coursework, and an additional 37 programs are listed as hybrid programs (BACB, 2016). Therefore, approximately 50% of the available coursework in behavior analysis is delivered online. With the number of online learning environments continuing to increase (Driscoll et al., 2012), it is important to establish sound teaching practices that continue to promote the acquisition of knowledge.

A number of risks are associated with sub-par or even status quo educational experiences. Ultimately, the end products of behavior analytic educational programs that produce practitioners are behavioral interventions that aim to improve the lives of clients and their families; educational experiences that do not impart the requisite knowledge for this task can result in diluted services at the expense of the most vulnerable populations (Roll-Pettersson, Ala’i-Rosales, Keenan, & Dillenburger, 2010). Furthermore, limited or inappropriate training within such programs might lead to misinformed graduates who could potentially place the integrity and credibility of the field in jeopardy, due to a lack of appropriate education and experience (Roll-Pettersson et al., 2010). With the additional flexibility and variety of instructional formats available to students and instructors, challenges and opportunities are abounding.

Despite the increase in utilizing online learning practices, there appears to be a relative dearth of empirically based studies with a focus on teaching the next generation of researchers and practitioners, using novel online pedagogy within the field of behavior analysis. The pedagogical literature within behavior analysis includes methods for promoting active learning in the face-to-face classroom, under the rubric of such topics as precision teaching, personalized system of instruction, guided notes, response cards, and interteaching (Austin, 2000; Querol, Rosales, & Soldner, 2015).

While the above methodologies have been proven effective for use within the classroom, further investigation would be beneficial in the online classroom environment. Most traditional classroom instructional methods must be adapted to fit within online platforms. Unlike traditional learning environments, online learning frequently requires asynchronous instruction, i.e., methods that grant students the ability to access course materials anytime, anywhere.

A particularly popular variant of asynchronous learning is the online discussion forum; unfortunately, research within this arena is lacking, particularly within the scope of teaching behavior analysis. Readily available research can be found primarily in journals with a specific focus on online instruction in which the main method of evaluation involves questionnaires delivered to students relating to classroom community and perceived learning or opinion surveys distributed to faculty on their experiences with creating and delivering asynchronous online courses (e.g., Coppola, Hiltz, & Rotter, 2002; Ocker & Yaverbaum, 1999). While it has been shown that asynchronous learning is as effective as traditional classroom environments, objective measures of student performance within this arena seem limited.

Driscoll et al. (2012) and Jorczak and Dupuis (2014) evaluated the impact of an online learning arrangement, which included asynchronous discussion as a component of instruction on one and two testing occasions, respectively. The results of the above studies were inconsistent, with findings of either slightly improved performance in face-to-face instruction relative to asynchronous online discussion (although any differences were likely due to a sampling effect) (Driscoll et al., 2012) or the converse (Jorczak and Dupuis, 2014). While these studies provide some insight to the utility of asynchronous learning, repeated measures and replication of performance effects would add to the validity of the findings. Additionally, the primary purpose of both of the above studies was to compare an online learning arrangement with traditional classroom instructional delivery; although the efficacy of asynchronous discussion was evaluated relative to in-person, synchronous discussion, the above studies did not evaluate whether the inclusion of discussion alone had an impact on student performance.

The purpose of the current study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the inclusion of asynchronous online discussion, within an online master’s level course in single-subject research methods, on students’ performance on quizzes and responding to a social validity questionnaire, when compared to a treatment-as-usual online classroom structure.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from two sections of a master’s level online course on single-subjects research design. All participants were female students who attended a mid-western university; all participants were professionally employed and over the age of 18. Participants were recruited via email, in order to obtain consent for the use of their data within this study. Consent was obtained from a total of 25 out of 35 students enrolled in two sections of the course. Participants were assigned to both the experimental (n = 12) and control groups (n = 11), strictly based on the section in which they were enrolled. Participants were distributed into one of two sections based on the order of registration by an administrative staff; the administrative staff assigned the first half of students registered to one section and the second half to a second section, in order to obtain a nearly equal number of students per section. The experimenters arbitrarily chose the first section as the experimental group. Participants were given extra credit for taking part in the study and for providing feedback via a social validity questionnaire. Participants’ data were included in the study if consent was obtained and if they met the criteria of participating in the course as designed. Participants’ data were excluded from the study given the following criteria: (1) two or more quizzes were completed at a time other than the regularly scheduled time, (2) two or more quizzes were not completed, or (3) the student did not participate in two or more required asynchronous discussion forums. As a result of the exclusionary criteria, two students’ data were removed from this analysis.

Setting and Materials

The study was conducted within the Southern Illinois University’s Behavior Analysis and Therapy, online master’s program. The same instructor and teaching assistant delivered both sections of the course. The course spanned an 18-week period, in which all coursework was delivered using the Desire 2 Learn (D2L) teaching and learning online platform. D2L was used for all instructional delivery and communication with students including quizzes, posted readings, study questions, pre-recorded lectures, and a general discussion forum for the purpose of posting announcements, updates, reminders, and comments pertaining to the course. Additionally, the experimental group was given access to, and required to participate in, an asynchronous online discussion forum.

Variables, Response Measurement, and Reliability

The primary dependent variable was the overall mean quiz score per participant. Quiz scores were obtained from the D2L platform, which was set to “auto grade” all quizzes. Measures of social validity were collected using a 14-question survey (Appendix 1) delivered at the conclusion of the course. The independent variable was the required participation in online asynchronous discussion. Again, D2L was used in order to obtain an accurate measurement of participation (the response requirement to receive full grades is described below).

Procedures

This study utilized a between-group design involving students enrolled in two sections of the same course. Participation in the study varied along a single component. One section was required to participate in asynchronous online class discussion (experimental group) while the other section was not required to engage in asynchronous discussion (control group). The above variation between sections occurred regardless of consent to participate in this study; however, only data gathered from students who did consent to participate was used for comparison.

Teaching methods were consistent across both the experimental and control groups. Instruction for both groups consisted of the following: (1) pre-recorded instructor lectures, (2) optional study questions for each assigned reading (responses were not submitted to instructors), and (3) group assignments in the form of written projects and recorded presentations of two hypothetical research studies.

Performance within the course was measured using quiz scores. A total of ten quizzes were delivered throughout the semester to coincide with each of the ten units of instruction. The study made use of the data from nine quizzes; one quiz was eliminated from the analysis due to an error in programming that provided one group extra time to complete the quiz. Quizzes were completed simultaneously by all participants at a pre-determined time on a weekly basis and were 30 min in duration. Quizzes contained 20 multiple-choice questions, five fill-in-the-blank questions, and five true-or-false questions. The “random section” function of D2L was used in the delivery of all quiz questions, which ensured that each participant received questions that were randomly chosen from a bank of questions created by the first author, based on required readings and lectures.

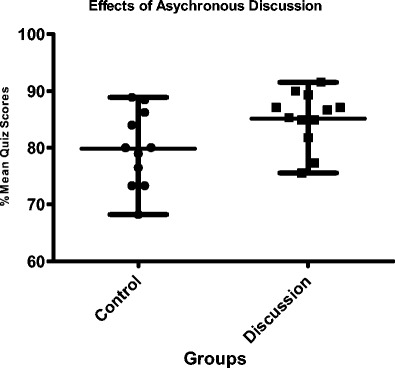

Finally, the experimental group was required to participate in asynchronous class discussions throughout the duration of the course. Four discussion questions were posted for each of the ten modules. The response requirement of asynchronous discussion consisted of student’s responding to each questions posed by the instructor and four posts in response to fellow classmates per module. Participants were required to first respond to instructor posts and then following 48 h, to respond to peers’ responses. Students were awarded grades for discussion (15 points per module, out of 700 total points), based on a minimum criterion of posts containing at least eight sentences, including at least two detailed references to assigned readings (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mean quiz scores per student for both groups of participants

Results and Discussion

An independent sample t test was conducted to determine differences in overall mean quiz scores, per participant, between the control and experimental groups (Table 1). There was homogeneity of variances for overall mean quiz scores, per participant for both groups, as assessed by Levene’s test for equality of variances (p = .26), indicating that there were no outliers in the data. Overall mean participant quiz scores were higher for students in the experimental group (M = 85.13, SD = 4.83) than the control group (M = 79.81, SD = 6.68). A statistically significant difference was found at 95% CI, M = −5.31; t(21) = −2.20, p = 0.039.

Table 1.

Mean quiz scores per student

| M | (SD) | N | t, df | Unpaired t test p value |

Significant (CI = 0.95) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discussion | 85.13 | (4.83) | 12 | t = −2.20 df = 21 | 0.039* | Yes |

| No discussion | 79.81 | (6.68) | 11 |

*p > 0.05

Social validity results indicated that mean responses across 14 questions, between groups, did differ slightly. Responses by students in the experimental group were more favorable (M = 4.195, SD = 0.50) than the control group (M = 4.00, SD = 0.47). The experimental group responded more favorably to the following questions: “I felt like I was a member of a learning community during in this class” (M = 4.54, SD = 0.93), “I felt comfortable participating in this course” (M = 4.90, SD = 0.30), “I was able to express my thoughts and feelings on the subject matter during this class” (M = 4.73, SD = 0.65), “I was able to form distinct individual impressions of my instructors during this class” (M = 3.36, SD = 1.21), “The pre-recorded instructor presentations influenced me to look further into topics that peaked my interest” (M = 4.18, SD = 1.08), “I felt secure in what I needed to know during this class” (M = 4.10, SD = 0.88), “The amount of interaction with instructors during this course was appropriate” (M = 3.55, SD = 1.30), “The amount of interaction with other students in this course was appropriate” (M = 4.09, SD = 1.30), “I was able to develop problem-solving skills throughout this course” (M = 4.45, SD = 0.82), “The material provided in this course allowed me to develop new skills and knowledge” (M = 4.82, SD = 0.60), and “Overall, I am satisfied with this course” (M = 4.54, SD = 0.93). These results indicate that students in the experimental group generally reported feeling part of the learning community and feeling that the online environment was conducive to learning. On the other hand, the control group responded more favorably to the questions, “I was able to comprehend the materials provided” (M = 4.38, SD = 0.74), “I was able to form distinct individual impressions of other classmates during this class” (M = 4.00, SD = 1.07), and “The online learning environment positively influenced the frequency and/or quality of my work” (M = 4.00, SD = 1.07). Due to the requirement of group work assignments for both sections of the course, these responses cannot solely be attributed to the manipulation of the independent variable.

These results were consistent with Jorczak and Dupuis (2014), who found that student performance on exams was higher in a group assigned to asynchronous online discussion. Additionally, the current study extended the results of Jorczak and Dupuis (2014) by incorporating graduate students enrolled in behavior analysis coursework as well as including objective and repeated measures of performance in the form of quiz scores. Furthermore, the finding that quiz scores were improved due to the implementation of active learning pedagogy when compared with passive learning pedagogy (e.g., lecture) is consistent with the findings of previous behavior analytic research conducted in traditional classroom settings (e.g., Williams, Weil, & Porter, 2012). The requirement of generating responses to questions based on concepts in assigned readings and generating novel and critical responses to peers may aide in abstracting concepts and, consequently, may have influenced the participant’s ability to obtain greater quiz scores. However, it could be argued that the requirement of making extra contact with any subject matter should logically result in greater performance when tested on that content. Controlling for time spent engaging with course material may be necessary to demonstrate that asynchronous discussion as a method of instructional delivery, rather than simply extra contact with material, is a moderator for increased scores. Future studies may control the above factor by making instructional materials only available within an online learning platform that is capable of tracking students’ time spent actively logged in.

An additional limitation of the current study is that the data was gleaned from only a single sample. The potential that groups were not evenly distributed was not ruled out. The differences found in student performance may have been influenced by a sample bias, given that students who registered for the course earlier were placed in the experimental group. Both pre-tests of competency with the subject matter and replication would strengthen the internal and external validity of the findings. In the event that a between-group design is not feasible, researchers may consider the use of the alternating treatment design in order to demonstrate within-subject effects, similar to Williams et al. (2012), who were convincingly able to establish the benefits of using guided notes in the classroom. Additionally, given the number of hybrid course offerings cited above, it may be beneficial to evaluate the effectiveness of asynchronous online discussion as an additional component within traditional classroom delivery. Future research may also consider the evaluation of other typical components of online teaching methods using a similar research design; potential areas of study may include varying instructor presence, online chats, and asynchronous lectures.

Advances and adoption of technology in the delivery of behavior analytic coursework may provide instructors with an exciting opportunity to deliver content to students using novel pedagogy. However, the field would benefit greatly from a critical evaluation of the efficacy of emerging teaching practices, as well as passive and synchronous teaching methods that mimic traditional lecture formats. It is of the upmost importance to our field that researchers advance the state of knowledge and that instructors practice in accordance with best practices, based on a body of evidence. Ultimately, the benefactors of advances in instructional delivery are the individuals who behavior analysts serve.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 21 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

This study received no funding of any kind.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Austin JL. Behavioral approaches to college teaching. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. In: Austin J, Carr J, editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. Reno: New Harbinger Publications; 2000. pp. 449–472. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2016). Approved University Training. http://info.bacb.com/o.php?page=100358. Accessed 16 July 2016.

- Coppola NW, Hiltz SR, Rotter NG. Becoming a virtual professor: pedagogical roles and asynchronous learning networks. Journal of Management Information Systems. 2002;18(4):169–189. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2002.11045703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll A, Jicha K, Hunt A, Tichavsky L, Thompson G. Can online courses deliver in class results? A comparison of student performance and satisfaction in an online versus a face-to face introductory sociology course. Teaching Sociology. 2012;40:312–331. doi: 10.1177/0092055X12446624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorczak RL, Dupuis DN. Differences in classroom versus online exam performance due to asynchronous discussion. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2014;18(2):n2. [Google Scholar]

- Ocker RJ, Yaverbaum GJ. Asynchronous computer-mediated communication versus face-to-face collaboration: results on student learning, quality and satisfaction. Group Decision and Negotiation. 1999;8(5):427–440. doi: 10.1023/A:1008621827601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Querol BID, Rosales R, Soldner JL. A comprehensive review of interteaching and its impact on student learning and satisfaction. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. 2015;1(4):390–411. doi: 10.1037/stl0000048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roll-Pettersson L, Ala’i-Rosales S, Keenan M, Dillenburger K. Teaching and learning technologies in higher education: applied behaviour analysis and autism; “necessity is the mother of invention”. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2010;11(2):247–259. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2010.11434349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams WL, Weil TM, Porter JC. The relative effects of traditional lectures and guided notes lectures on university student test scores. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2012;13(1):12–16. doi: 10.1037/h0100713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 21 kb)