Pramipexole, a dopamine agonist drug, is prescribed for Parkinson's disease (PD). Recently, three studies showed a possible link between this drug and heart failure (HF).1, 2, 3 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, in September 2012, warned of a possible increased risk of HF with pramipexole treatment.4 We report on the case of one particular patient who developed reversible HF most likely related to pramipexole.

Case Study

A 62‐year‐old man with a 10‐year history of PD was given pramipexole. His medical history was unremarkable. There was no history of diabetes. The patient did not smoke and did not have other coronary artery disease (CAD) risk factors. He did not use any drugs; in particular, he never used cocaine. The patient reported a history of atrial fibrillation, but during electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring, no atrial fibrillation or any other rhythm disturbance could be observed. The diagnosis of PD was confirmed in 2000. The patient was treated with pergolide (0.15 mg/day) for 3 weeks, but stopped this drug because of nausea. Ropinirole (3 mg/day) was then taken for 5 months and stopped because of the absence of clinical efficacy. The patient was then treated only with levodopa and entacapone. Rasagiline was added in 2008. In 2010, because of severe motor fluctuations, pramipexole (2.1 mg/day) was added. After 1 year of taking pramipexole, the patient was hospitalized because of significant lower‐limb edemas. He did not complain of any heart issues, but during the systematic checkup, the cardiac catheterization showed HF with a capillary wedge pressure of 23 mmHg (normal value: <12 mmHg). The echocardiograph showed a mild mitral insufficiency and a dilatation of the inferior vena cava and both atria. At that point, his treatment consisted of l‐dopa (600 mg daily), rasagiline (1 mg daily), and pramipexole (2.1 mg/day). Because of the leg edemas, the dose of pramipexole was reduced by half. The patient was administered 40 mg twice‐daily of furosemide. The limb edemas were resolved, and cardiac function recovered.

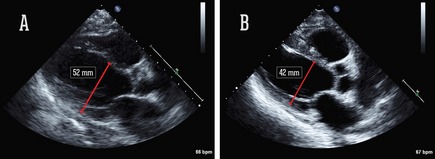

Two months later, the patient was hospitalized for asthenia and edemas. At that time, he was taking pramipexole (0.35 mg three times daily [TID]). The next day, he experienced shock resulting from severe bradycardia (30/min) that led to 5 minutes of reanimation, intubation, and admission to intensive care. The diagnosis of HF was confirmed using echocardiography, which showed severely impaired left ventricular (LV) function and a mild mitral insufficiency (Fig. 1). The coronary angiography was normal. His blood sample was characterized by elevated troponin‐I (1.93 mg/mL, Nl <0.08) and CPK‐MB (4.1 μg/L, Nl <3.5). The ECG revealed a modification in the repolarization of the precordial leads without signs of necrosis or ischemia. Pramipexole and rasagiline were stopped immediately, while l‐dopa was maintained at 100 mg six times daily. This resulted in a quick heart function recovery and no relapse, confirmed using a cardiac MRI, which showed no late enhancement, necrosis, fibrosis, or inflammation. The ejected fraction was estimated to be 59%.

Figure 1.

Echocardiograph findings: parasternal long axis view, with diastolic LV dimension at the baseline (A) and after functional recovery (17 days later) (B).

Two years later, his echocardiograph showed normal LV function with a mild mitral insufficiency.

Discussion

This case reveals a probable link between pramipexole, a nonergot dopamine agonist, and a reversible HF. None of the HF causes described in the European Society of Cardiology5 could explain this dysfunction. One of the main causes of HF is CAD, which was ruled out by the normal coronary angiogram. Significant valvular heart disease was also excluded through echocardiography, and the valvular lesion (trivial mitral regurgitation) did not justify HF. After the initial bradycardia, the ECG did not show any arrhythmia susceptible to inducing HF. Apart from pramipexole, there were no other noncardiovascular precipitating factors (infection, major surgery, asthma, alcohol abuse, endocrine disease, and so on).

The patient had been taking pramipexole for 1 year at a regular dose (0.7 mg TID) when he was hospitalized for significant lower‐limb edema. These edemas disappeared when the dose of pramipexole was reduced by half (0.35 mg TID). Although the full dose of pramipexole was not rechallenged, 2 months later, while taking a half dose, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for HF. The decision was made to stop pramipexole definitively. His heart function recovered completely, and 2 years later, no sequelae could be found.

The hypothesis that arises from this case study is that HF may be caused by pramipexole and is reversible once the drug is stopped.

Three different case‐control studies show that pramipexole increases the risk of HF. Mokhles et al.1 found that this increased risk is especially high during the first months of treatment in PD patients over the age of 80. Ergot and other nonergot dopamine agonists were not associated with HF. Renoux et al.2 also highlighted a higher risk with pramipexole, compared to the other dopamine agonists used in treating PD and RLS. In a cohort of 26,814 subjects taking dopamine agonists, the incidence rate of HF was increased with the current use of a dopamine agonist, higher for pramipexole and cabergoline, but was not significant for ropinirole or pergolide. The increased risk for pramipexole was, however, not significant, when compared with all dopamine agonists taken collectively. We can therefore conclude that the increased risk of HF is not a class effect and that the increased risk is unrelated to the ergoline structure. Hsieh and Hsiao3 studied this risk among Asian patients. They found an increased, but nonsignificant, risk with pramipexole proportional to the duration of use. In this study, HF was not found in patients with a history of peripheral edema, the mechanism most likely being different. Pergolide, another dopamine agonist, is known to cause HF. This ergot‐derived drug stimulates the 5HT2B receptor, leading to valvular hypertrophy.6 This is not the case here. In addition to a high affinity for the dopamine D2, D3, and D4 receptors, pramipexole is also an alpha‐2‐adrenergic receptors agonist.7, 8 It is thus possible that pramipexole directly activates the α2‐adrenergic autoreceptors, reducing adrenergic tone and myocardial contractility.

Although further studies are warranted, especially to demonstrate the mechanism of cardiac toxicity, clinicians should pay close attention to heart function throughout pramipexole exposure, especially because it can be reversible.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

M.A.: 1B, 1C, 3A

A.P.: 1C

A.J.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: The authors declare that there are no disclosures to report.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Mokhles MM, Trifirio G, Dieleman JP, et al. The risk of new onset heart failure associated with dopamine agonist use in Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Res 2012;65:358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Renoux C, Dell'Aniello S, Borphy JM, Suissa S. Dopamine agonist use and the risk of heart failure. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hsieh PH, Hsiao FY. Risk of heart failure associated with dopamine agonists: a nested case‐control study. Drugs Aging 2013;30:739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . FDA drug safety communication: ongoing safety review of Parkinson's drug Mirapex (Pramipexole) and possible risk of heart failure. US Food and Drug Administration; Available at http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm319779.htm accessed (19 September 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 5. McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. AntoniniA A, Poewe W. Fibrotic heart‐valve reactions to dopamine‐agonist treatment in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:826–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piercy MF, Hoffmann WE, Smith MW, Hyslop DK. Inhibition of dopamine neuron firing by pramipexole, a dopamine D3 receptor‐preferring agonist: comparison to other dopamine receptor agonists. Eur J Pharmacol 1996;312:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chernoloz O, ElMansari M, Blier P. Sustained administration of pramipexole modifies the spontaneous firing of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin neurons in the rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009;34:651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]