Abstract

Background: The aim of this study was to describe a case of hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) resulting from SPG11 mutations, presenting with a complex phenotype of dopa‐responsive dystonia (DRD), diagnosed using whole exome sequencing (WES). HSP resulting from SPG11 typically presents with spasticity, cognitive impairment, and radiological evidence of thin corpus callosum. Initial presentation with DRD has not been previously reported on. Methods: This 11‐year‐old boy with delay in fine motor skills, presented at 8 years of age with progressive, generalized dystonia with diurnal variation, bradykinesia, and stiff gait. There was marked improvement in dystonia with levodopa, but he soon developed wearing‐off phenomenon and l‐dopa‐induced dyskinesia. Family history was unremarkable. Results: Brain MRI showed thinning of the anterior corpus callosum with periventricular white matter changes. 123I‐ioflupane single‐photon emission coupled tomography showed bilateral severe presynaptic dopamine deficiency. WES identified transheterozygous allelic variants in the SPG11 on chromosome 15, including a truncating STOP mutation (p.E1630X) and a second heterozygous coding variant (p.L2300R). Dystonia improved with globus pallidus internus (GPi) DBS surgery. Conclusions: HSP resulting from SPG11 should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with DRD, parkinsonism, and spasticity. This case expands the HSP genotype and phenotype. GPi DBS may be a therapeutic option in selected patients.

Keywords: SPG11, hereditary spastic paraplegia, thin corpus callosum, dopa‐responsive dystonia, parkinsonism

Hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorder characterized predominantly by progressive weakness and spasticity of the lower limbs.1 HSP can present with spasticity alone (uncomplicated) or spasticity associated with other neurological and non‐neurologic features (complicated or complex). To date, 72 different spastic gait disease loci have been identified, and 55 spastic paraplegia genes have already been cloned, which include autosomal‐dominant, autosomal‐recessive, and X‐linked forms of HSP.2

HSP resulting from SPG11 mutations is a common cause of autosomal recessive HSP, which typically presents clinically with spasticity, cognitive impairment, and peripheral neuropathy. Radiologically it is characterized by thinning of the corpus callosum (TCC) and periventricular white matter changes.3, 4 However, there is increasing recognition that mutations in SPG11 can cause heterogeneous clinical manifestations, including juvenile‐onset parkinsonism3, 5, 6, 7 and, rarely, dystonia (Table 1).3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10 Other HSPs can rarely have dystonia or parkinsonism.2

Table 1.

Summary of reported cases of SPG11 mutation associated with dystonia

| Case | Mutation 1 | Mutation 2 | Age at Evaluation /Sex | Presenting Symptom(s) | Age of Onset | Clinical Features | Brain Imaging | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Features | Parkinsonism | Dystonia | |||||||

|

Vanderver et al.8

Case 4 |

c.4222insA; p.1426X [STOPAA1426] | c.4777delA; p.1606X [STOPAA1606] | 25 F | Impaired balance | 12 | Spastic paraparesis, distal muscular atrophy, weakness of the hands, urinary incontinence, macular flecks involving the macular and perimacular area, mild sensory neuropathy | Rigidity of upper extremities, bradykinesia | Dystonia of toes | TCC and periventricular white matter abnormalities |

|

Yoon et al.9

Case 8 |

c.3664_3665insT (p.Lys1222IlefsX15) | r.4667_4774del | 17 F | Gait abnormality, poor coordination | 6 | Learning disability, bladder dysfunction, falls, speech abnormalities, cognitive decline | Bradykinesia | Dystonia(not specified) | TCC |

|

Stevanin, et al.3

FSP870‐17 |

c.733_734delAT, p.M245VfsX246 | c.733_734delAT, p.M245VfsX246 | 25/M | Stiff legs | 15 | Cognitive impairment, pes cavus, renal lithiasis | None | Facial dystonia | Not available |

|

Stevanin et al.3

FSP870‐20 |

c.733_734delAT, p.M245VfsX246 | c.733_734delAT, p.M245VfsX246 | 28/M | Weakness legs | 17 | Severe weakness, intellectual disability | None | Dystonia of face and tongue | Not available |

| Paisan‐Ruiz, et al.7 |

Frameshift p.His235ArgfsX12 |

p.His235ArgfsX12 | 27 M | Postural and writing tremor | 14 | Walking difficulties with imbalance, speech problems, and slowness, progressively stiff and he complained of leg weakness and falls, brisk reflexes, ankle clonus | Facial hypomimia, writing tremor, axial rigidity and bradykinesia | Laryngeal dystonia, hand dystonia | MRI brain generalized atrophy with a TCC. DaT‐SPECT decreased bilateral putaminal and caudate uptake |

| Guidubaldi et al.5 | c.3664insT (p.K1222IfsX13) | c.6331insG (p.E2111GfsX36) | 32 F | Abnormal gait and progressive rigidity | 14 | Dysarthria, postural instability, severe spastic paraparesis, generalized brisk reflexes, and bilateral pes cavus with extensor plantar response, mild cerebellar signs, mild dysphagia, and urinary urgency, memory and executive functions | Wearing‐off phenomenon and “peak‐dose” dyskinesias, featuring facial, bilateral resting tremor, and mild bradykinesia | OFF dystonia. No further description | Pronounced TCC, diffuse cortical cerebral and mild cerebellar atrophy, and hyperintense T2‐weighted lesions in periventricular regions. DaT‐SPECT was consistent with severe, bilateral symmetrical nigrostriatal loss |

|

Paisan‐Ruiz et al.10

Family 4 |

Sequence variant p.A59V of unknown significance. Identified as a heterozygote in one control | 24 F | Walking difficulty | 13 | Axonal neuropathy, cognitive impairment, brisk reflexes, extensor plantar, severe ataxia | None | Severe dystonia in the limbs and torticollis, spastic dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, hypometric saccades, slow tongue | Borderline TCC and cerebellar atrophy | |

Dopa‐responsive dystonia (DRD) is characterized by childhood‐onset dystonia, diurnal fluctuation of symptoms, and a dramatic response to levodopa therapy.11 Parkinsonian features may appear later in the course of the disease and in adult family members. A minority of patients may have hyperactive deep tendon reflexes and an apparent extensor plantar response.12 The majority of reported cases of DRD have been a result of mutations in genes that encode enzymes involved in the endogenous dopamine biosynthesis pathway, such as GTP cyclohydrolase (GCH‐1) deficiency, as well as tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and sepiapterin reductase deficiency.13 There are other rare causes of the DRD phenotype, which include 6‐pyruvoyl‐tetrahydropterin synthase deficiency,14 PARK2,15 SCA3,16 and ATM.17

Here, we describe a unique case of HSP associated with SPG11 mutations, diagnosed by whole exome sequencing (WES), that presented with a phenotype of dopa‐responsive dystonia, spasticity, and parkinsonism.

Case Report

An 11‐year‐old boy was initially evaluated at our clinic because of abnormal posturing of the limbs. He was born full term, but his birth was complicated by fetal distress and bilateral pneumothorax, followed by chronic interstitial pulmonary dysfunction, which improved over the next few years. He had some delay in motor milestones, but with intensive physical therapy, he was able to run and walk well, although he continued to have mild impairment in fine motor function.

At 8 years of age, he started to drag his left leg while walking and developed similar symptoms in the right leg a few weeks later. He had abnormal posturing of the left arm characterized by abduction of the shoulder as well as flexion at the elbow with the arm behind the head. Subsequently, he developed abnormal posturing of the right arm. Jerky tremor was also noticed bilaterally in the hands while reaching to grab objects. Over time, he also developed bilateral upper‐extremity rest tremor. His gait became stiff and he developed postural instability and near falling. At the beginning the patient's parents noticed marked diurnal variation in his symptoms: He was generally well upon awakening and became progressively worse by the end of the day. His symptoms also improved after a nap. Within 1 year, his condition progressed such that he became increasingly dependent on a wheelchair. He also developed urinary incontinence. In addition to progressive motor and autonomic symptoms, he exhibited attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive‐compulsive disorder, and anxiety. In 2011, at the age of 9 years, he was suspected to have DRD and was given a trial of carbidopa/l‐dopa (25/100 mg three times a day) resulting in marked improvement in all motor symptoms. However, within a few months, he experienced wearing off, requiring increased frequency of l‐dopa doses to four times daily.

The patient was first evaluated at our clinic in 2013 at the age of 11. He was examined 2 hours after the last dose of l‐dopa while in the ON state (see Video 1). There was evidence of irregular jerky movements of the head and trunk at rest, which worsened with movement. He also had irregular jerky movements of both arms on finger‐to‐nose maneuver and in posture holding, suggestive of dystonic tremor. He had dystonia in both arms, worse on the left with flexion of the wrist and fingers, and extension of the fingers on the right. Fine finger movements were slow and deliberate without decrementing amplitude. There was extension of the left leg with eversion and slight extension of the foot, especially at rest. Five and a half hours after the last dose of l‐dopa while in the OFF state (see Video 1), the patient had marked worsening of dystonia with moderate left torticollis and retrocollis at rest. Dystonia was also worse in the extremities, especially in the right leg. He also had mild intermittent opisthotonic extension of the trunk, which limited his gait and resulted in near falls in the absence of support. Dystonic tremors were more pronounced when off medications. Reflexes were brisk, particularly in the lower extremities with 6 to 8 beats of ankle clonus and bilateral extensor plantar response. There was no ataxia or dysmetria.

The patient continued to experience wearing off, and when the l‐dopa dose was further increased, he developed l‐dopa‐induced choreiform peak‐dose dyskinesia involving the face and arms (see Video 1). He had similar dyskinesia while on trihexyphenidyl, which was later discontinued. Ropinirole and amantadine were also tried, but did not provide meaningful benefit. The duration of l‐dopa response became progressively shorter and his OFF periods were characterized by progressively worse generalized dystonia as well as speech difficulty, palpitations, anxiety, and nausea. He denied any sensory symptoms in the legs, and the sensory examination was normal.

A neuropsychology evaluation performed 2 years before the onset of motor symptoms met criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD and impaired verbal IQ. Comprehensive retinal examination by an ophthalmologist was unremarkable. A maternal great grandmother had Parkinson's disease in her 70s, but there was no other family history of dystonia or parkinsonism. The parents, who are of Western European descent, are healthy and there is no known history of consanguinity in the family. He has one younger brother who is healthy.

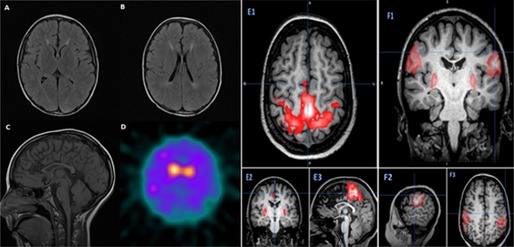

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) neurotransmitter assessment (performed before commencement of dopaminergic medications) revealed low levels of both tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) at 7 nmol/L (9–40 nmol/L) and homovanillic acid (HVA) at 204 nmol/L (218–852 nmol/L), but normal levels of 5‐hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5‐HIAA) 133 nmol/L (range, 66–338), neopterin 16 nmol/L (range, 7–40), and 3‐O‐methyldopa 12 nmol/L (<100 nmol/L). Genetic testing for Friedreich's ataxia was negative. EEG did not show any epileptiform activity. Brain MRI showed periventricular hyperintense T2‐weighted lesions and TCC, especially the anterior half (Fig. 1A–C). He underwent 123I‐ioflupane single‐photon emission coupled tomography (DaT‐SPECT), which showed essentially absent tracer uptake in bilateral putamina with marked reduced uptake in the caudate nuclei, with slightly greater reduction in the left caudate nucleus compared to the right (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

(A and B) Axial T2 fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery showing increased T2 signal in the periventricular white matter. (C) Sagittal T1‐marked thinning of the anterior half of the corpus callosum. (D) DaT‐SPECT showing essentially absent tracer activity in bilateral putamina and reduced uptake in caudate with slightly greater reduction in left caudate nucleus, compared to the right. (E) 1–3: Sedated resting‐state fMRI of motor function was atypical in that bilateral leg network and also includes bilateral hand and putamen. (F) 1–3: Sedated resting‐state fMRI of motor function was atypical in that bilateral sensory‐face area includes the putamen.

Given the unusual and complex phenotype in this case, the number of potentially contributory genetic syndromes, as well as the remote possibility of a novel underlying condition, blood was sent for WES, rather than targeted genetic testing. WES was performed by the Medical Genetics Laboratories (MGL) at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM; Houston, TX), which is certified by the College of American Pathologists and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Discovered variants are interpreted in accordance with guidelines from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). The analysis pipeline and interpretation of WES by the BCM‐MGL for use in clinical practice has been previously reported on in detail and validated in a large, clinical case series.18

Genetic analysis

WES of our patient revealed a mutation, c.4888G>T (p.E1630X), in the SPG11 gene on chromosome 15:4881468, predicted to introduce a premature STOP within exon 28, and consistent with a pathogenic allele based on established guidelines.19 A second heterozygous variant in SPG11 c.6899T>G (rs371334506, chromosome 15: 44858152) was also discovered. This is a rare missense variant within exon 38, predicted to result in a leucine to arginine change at position 2300. Based on publicly available exome data (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), this variant has previously been observed only once in 8,596 control chromosomes from individuals of European‐American ancestry (minor allele frequency: ~0.01%). Both variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing in our patient. In addition, targeted SPG11 sequencing of both parents demonstrated unambiguously that the p.E1630X and p.L2300R alleles were inherited from the father and mother, respectively, establishing these variants in the transheterozygous configuration in our patient. Although the p.L2300R change is classified as a variant of unknown clinical significance (VUS) based on ACMG guidelines, it is predicted to be damaging by the sorting intolerant from tolerant technique20 and probably damaging by PolyPhen‐2,21 two validated algorithms for predicting the consequences of protein amino acid substitutions.19 WES did not identify a GCH‐1 mutation.

Notably, another heterozygous variant of unknown clinical significance, in the MTPAP gene c.410A>T(p.Q137L), was also discovered in our patient, which is a novel variant, based on public databases. Defects in this gene cause autosomal‐recessive spastic ataxia 4 (p.SPAX4) MIM:613672. A second candidate variant or mutation was not discovered, consistent with the recessive nature of this condition, although the presence of a deletion or duplication cannot be definitively ruled out based on the WES results. Furthermore, our patient did not demonstrate ataxia, a core clinical feature of this rare genetic disorder, described to date only in a single large Amish family.22

Our patient continued to have progressively shorter response to l‐dopa over time and additionally developed intermittent episodes of generalized dystonia associated with speech difficulty, diaphoresis, and severe anxiety. These periods occurred during medication wearing off, which were very disabling for the patient and affected his overall quality of life. On the other hand, bothersome l‐dopa‐induced choreiform dyskinesia (see Video 1) limited the frequent dosing of l‐dopa. Although previous experience is lacking, DBS surgery was considered a potential treatment option for management of generalized dystonia.

The response to DBS was assessed using the Burke‐Fahn‐Marsden Dystonia Rating Scale (BFMDRS).23 BFMDRS score before surgery in the OFF‐state was 24.5 and in the ON‐state was 13.5. The patient's performance on neuropsychology testing was limited by worsening of dystonia at first and then by development of dyskinesia during the testing period. Before surgery, he underwent fluorodeoxyglucose PET, which was normal, and resting‐state functional MRI (fMRI) showed evidence of cortical‐basal ganglia overconnectivity (Fig. 1E1–3 and F1–3).

He underwent bilateral globus pallidus internus (GPi) DBS surgery in June 2014 with microelectrode recordings for target localization. Two months after implantation of the DBS and after completing 2 programming sessions, he showed a moderate reduction in the number and severity of dystonic episodes related to the wearing‐off periods. The BFMDRS off medications with the DBS turned on was 9.

Discussion

We discovered a novel, compound heterozygous genotype at the SPG11 gene as the most likely cause of the clinical phenotype in our patient. Of the two SPG11 allelic variants identified, the premature nonsense variant (p.E1630X) is a potentially truncating mutation and is pathogenic based on ACMG guidelines.19 Whereas the p.L2300R variant, by contrast, is formally classified as a VUS, this rare missense change is found to be deleterious based on two independent algorithms. Furthermore, Sanger sequencing of the parents established these alleles to be in the transheterozygous configuration, consistent with the autosomal‐recessive inheritance of SPG11‐associated HSP. Finally, as discussed below, we believe the phenotypic overlap between our case presentation and previous reports establishes HSP resulting from SPG11 mutations as the most likely molecular diagnosis. To date, at least 127 distinct mutations in the SPG11 gene have been reported.24 SPG11 (MIM610844) maps to chromosome 15q13–15 and encodes spatacsin, a protein of unknown function. The protein has been associated with cytoskeleton, endoplasmic reticulum, and vesicles involved in protein trafficking, suggesting a potential role in axonal transport.25, 26 Spatacsin has also been identified as a component of Lewy bodies and glial cytoplasmic inclusions.27 This new compound heterozygous mutation in our patient broadens the potential allelic spectrum in SPG11‐associated HSP.

The mean age at onset of HSP resulting from SPG11 mutations is 12 years (range, 2–23) with initial presentation of difficulty with ambulation (57%), which may be preceded by intellectual disability in up to 19% of patients.25 Our case expands the clinical phenotype associated with SPG11 mutations to include predominantly early dystonia with diurnal fluctuation and robust l‐dopa‐responsive dystonia mimicking a DRD phenotype. Additionally, a rapidly progressive course demonstration of “wearing‐off phenomenon” and the occurrence of l‐dopa‐induced dyskinesia (see Video 1) within a few months of starting l‐dopa therapy were unusual. The DaT‐SPECT imaging was abnormal (Fig. 1D), indicating presynaptic dopamine neuronal dysfunction, which is a hallmark of neurodegenerative parkinsonism. l‐dopa‐induced dyskinesia has been previously reported in a case of juvenile‐onset parkinsonism resulting from SPG11 5 (Table 1), and there are several reported cases of SPG11 mutations5, 6, 7 with parkinsonism having abnormal DaT‐SPECT. However, not all cases of SPG11 deficiency are accompanied by parkinsonism, and it is likely a unique phenotypic variant of this condition. By contrast, DaT‐SPECT is negative in cases of DRD resulting from GCH‐1 and TH deficiency, consistent with preserved striatal dopaminergic presynaptic nerve terminals.28, 29, 30 TCC with periventricular white matter change, as observed on MRI in our patient, is most commonly observed in SPG11 mutations; however, it can be also observed in SPG15 and, rarely, in cases with SPG 21, SPG35, SPG48, and SPG54.31

Previous studies have also found CSF neurotransmitter metabolite abnormalities in SPG11. One study evaluating neurotransmitter metabolites in 4 patients with SPG11 mutations showed low concentration of HVA (3 of 4), which is the main metabolite in the catabolic pathway of dopamine, and low concentration of BH4 (3 of 4) and normal neopterin (all 4), similar to our patient. 5‐HIAA was normal in 3 of 4 patients.8 The mechanism leading to neurotransmitter abnormalities in SPG11 patients is not known and further studies are needed.

WES, which played a key role in our diagnosis of this patient, is finding increasing clinical utility in patients with presumed genetic syndromes.18, 32, 33 Given the unusual, complex clinical presentation, including dystonia and parkinsonism, and the known genetic heterogeneity underlying the suspected diagnosis of DRD, the alternative to WES would have been to pursue piecemeal testing for numerous individual gene mutations and/or testing for large panels of candidate genes causing overlapping syndromes. In retrospect, WES was the most efficient, cost‐effective option for initial genetic testing in such a circumstance. The increasing availability of WES in clinical practice will undoubtedly broaden the known clinical and etiological spectrum of DRD. Our case supports the notion that DRD is a syndrome with multiple etiologies and clinical phenomenologies.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of SPG11 gene mutations treated with GPi‐DBS surgery. Our results show that, in the short term, DBS surgery can be effective in improving generalized dystonia, reducing the wearing‐off periods and thereby reducing the bothersome dystonic episodes. We will continue to follow this patient to establish the long‐term response to DBS surgery.

In conclusion, HSP resulting from SPG11 mutations should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with DRD, parkinsonism, and spasticity. This unusual case expands the clinical phenotypes associated with this form of HSP and further adds to the heterogeneous genetic causes of DRD. DBS surgery may be an option in selected cases.

Author Roles

Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

S.W.: 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A

J.M.S.: 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

J.J.‐S.: 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

D.C.: 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C

J.J.: 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: J.J.‐S. has received research grants Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Inc., Sinea Biotech SPA, Phytopharm, Neurosearch Sweden AB, and Schering‐Plough; served in a consulting/advisory capacity with Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Medtronic, Inc, and St. Jude Medical; and has served on the speaker's bureau of Lundbeck, Inc., Medtronic, Inc., Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Allergan, Inc. J.J. has received current research and Center of Excellence grants from Adamas Pharmaecuticals, Inc (amantadine), Allergan, Inc (botulinum toxin), Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Inc (SD809), the CHDI Foundation, GE Healthcare, Great Lakes NeuroTechnologies, the Huntington's Disease Society of America, the Huntington Study Group, Ipsen Limited, Kyowa Haako Kirin Pharma, Inc (istradefylline), Lundbeck Inc (tetrabenazine), Medtronic, Merz Pharmaceuticals, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson Research, the National Institutes of Health, the National Parkinson Foundation, Omeros Corporation (OMS824), the Parkinson Study Group, Pharma Two B, Prothena Biosciences Inc (PRX002), Psyadon Pharmaceuticals (ecopipam), Inc, St. Jude Medical, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, UCB Inc, and University of Rochester, is currently a consultant or an advisory committee member with Allergan, Inc, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., Lundbeck Inc, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., and receives royalties from Cambridge, Elsevier, Future Science Group, Hodder Arnold, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, and Wiley‐Blackwell.

Supporting information

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video 1. The first part of the video, taken during the ON state, shows minimal hand dystonia and spastic gait. The second segment, recorded during the OFF state, showed prominent generalized dystonia with moderate left torticollis, retrocollis at rest, bilateral arm and right leg dystonia, dystonic tremor, and bradykinesia. The third segment shows generalized, predominantly choreic, l‐dopa‐induced dyskinesia.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the Caroline Weiss Law Fund for Research in Molecular Medicine and a Burroughs Welcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Fink JK. Hereditary spastic paraplegia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2006;6:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lo Giudice T, Lombardi F, Santorelli FM, Kawarai T, Orlacchio A. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinical‐genetic characteristics and evolving molecular mechanisms. Exp Neurol 2014;261C:518–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stevanin G, Azzedine H, Denora P, et al. Mutations in SPG11 are frequent in autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum, cognitive decline and lower motor neuron degeneration. Brain 2008;131:772–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siri L, Battaglia FM, Tessa A, et al. Cognitive profile in spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum and mutations in SPG11. Neuropediatrics 2010;41:35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guidubaldi A, Piano C, Santorelli FM, et al. Novel mutations in SPG11 cause hereditary spastic paraplegia associated with early‐onset levodopa‐responsive parkinsonism. Mov Disord 2011;26:553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anheim M, Lagier‐Tourenne C, Stevanin G, et al. SPG11 spastic paraplegia. A new cause of juvenile parkinsonism. J Neurol 2009;256:104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paisan‐Ruiz C, Guevara R, Federoff M, et al. Early‐onset L‐dopa‐responsive parkinsonism with pyramidal signs due to ATP13A2, PLA2G6, FBXO7 and spatacsin mutations. Mov Disord 2010;25:1791–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vanderver A, Tonduti D, Auerbach S, et al. Neurotransmitter abnormalities and response to supplementation in SPG11. Mol Genet Metab 2012;107:229–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoon G, Baskin B, Tarnopolsky M, et al. Autosomal recessive hereditary spastic paraplegia‐clinical and genetic characteristics of a well‐defined cohort. Neurogenetics 2013;14:181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paisan‐Ruiz C, Nath P, Wood NW, Singleton A, Houlden H. Clinical heterogeneity and genotype‐phenotype correlations in hereditary spastic paraplegia because of Spatacsin mutations (SPG11). Eur J Neurol 2008;15:1065–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Segawa M, Hosaka A, Miyagawa F, Nomura Y, Imai H. Hereditary progressive dystonia with marked diurnal fluctuation. Adv Neurol 1976;14:215–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Asmus F, Gasser T. Dystonia‐plus syndromes. Eur J Neurol 2010;17(Suppl. 1):37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clot F, Grabli D, Cazeneuve C, et al. Exhaustive analysis of BH4 and dopamine biosynthesis genes in patients with Dopa‐responsive dystonia. Brain 2009;132:1753–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hanihara T, Inoue K, Kawanishi C, et al. 6‐Pyruvoyl‐tetrahydropterin synthase deficiency with generalized dystonia and diurnal fluctuation of symptoms: a clinical and molecular study. Mov Disord 1997;12:408–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khan NL, Graham E, Critchley P, et al. Parkin disease: a phenotypic study of a large case series. Brain 2003;126:1279–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilder‐Smith E, Tan EK, Law HY, Zhao Y, Ng I, Wong MC. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 presenting as an L‐DOPA responsive dystonia phenotype in a Chinese family. J Neurol Sci 2003;213:25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Charlesworth G, Mohire MD, Schneider SA, Stamelou M, Wood NW, Bhatia KP. Ataxia telangiectasia presenting as dopa‐responsive cervical dystonia. Neurology 2013;81:1148–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang Y, Muzny DM, Reid JG, et al. Clinical whole‐exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1502–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Richards CS, Bale S, Bellissimo DB, et al. ACMG recommendations for standards for interpretation and reporting of sequence variations: revisions 2007. Genet Med 2008;10:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31:3812–3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non‐synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res 2002;30:3894–3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crosby AH, Patel H, Chioza BA, et al. Defective mitochondrial mRNA maturation is associated with spastic ataxia. Am J Hum Genet 2010;87:655–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burke RE, Fahn S, Marsden CD, Bressman SB, Moskowitz C, Friedman J. Validity and reliability of a rating scale for the primary torsion dystonias. Neurology 1985;35:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao W, Zhu QY, Zhang JT, et al. Exome sequencing identifies novel compound heterozygous mutations in SPG11 that cause autosomal recessive hereditary spastic paraplegia. J Neurol Sci 2013;335:112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stevanin G, Santorelli FM, Azzedine H, et al. Mutations in SPG11, encoding spatacsin, are a major cause of spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum. Nat Genet 2007;39:366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murmu RP, Martin E, Rastetter A, et al. Cellular distribution and subcellular localization of spatacsin and spastizin, two proteins involved in hereditary spastic paraplegia. Mol Cell Neurosci 2011;47:191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuru S, Yoshida M, Tatsumi S, Mimuro M. Immunohistochemical localization of spatacsin in alpha‐synucleinopathies. Neuropathology 2013;34:135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rajput AH, Gibb WR, Zhong XH, et al. Dopa‐responsive dystonia: pathological and biochemical observations in a case. Ann Neurol 1994;35:396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jeon BS, Jeong JM, Park SS, et al. Dopamine transporter density measured by [123I]beta‐CIT single‐photon emission computed tomography is normal in dopa‐responsive dystonia. Ann Neurol 1998;43:792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Naumann M, Pirker W, Reiners K, Lange K, Becker G, Brucke T. [123I]beta‐CIT single‐photon emission tomography in DOPA‐responsive dystonia. Mov Disord 1997;12:448–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pensato V, Castellotti B, Gellera C, et al. Overlapping phenotypes in complex spastic paraplegias SPG11, SPG15, SPG35 and SPG48. Brain 2014;137:1907–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bettencourt C, Lopez‐Sendon J, Garcia‐Caldentey J, et al. Exome sequencing is a useful diagnostic tool for complicated forms of hereditary spastic paraplegia. Clin Genet 2013;85:154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bainbridge MN, Wiszniewski W, Murdock DR, et al. Whole‐genome sequencing for optimized patient management. Sci Transl Med 2011;3:87re83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video 1. The first part of the video, taken during the ON state, shows minimal hand dystonia and spastic gait. The second segment, recorded during the OFF state, showed prominent generalized dystonia with moderate left torticollis, retrocollis at rest, bilateral arm and right leg dystonia, dystonic tremor, and bradykinesia. The third segment shows generalized, predominantly choreic, l‐dopa‐induced dyskinesia.