Abstract

Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV) is a rhabdovirus of the lyssavirus genus capable of causing fatal rabies-like encephalitis in humans. There are two variants of ABLV, one circulating in pteropid fruit bats and another in insectivorous bats. Three fatal human cases of ABLV infection have been reported with the third case in 2013. Importantly, two equine cases also arose in 2013; the first occurrence of ABLV in a species other than bats or humans. We examined the host cell entry of ABLV, characterizing its tropism and exploring its cross-species transmission potential using maxGFP-encoding recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses that express ABLV G glycoproteins. Results indicate that the ABLV receptor(s) is conserved but not ubiquitous among mammalian cell lines and that the two ABLV variants can utilize alternate receptors for entry. Proposed rabies virus receptors were not sufficient to permit ABLV entry into resistant cells, suggesting that ABLV utilizes an unknown alternative receptor(s).

Keywords: rhabdovirus, emerging, zoonosis, Australian bat lyssavirus, rabies virus, encephalitis, tropism, viral entry, receptor, envelope glycoprotein

Introduction

Until the discovery and isolation of Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV) from a black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) in 1996, Australia was considered free of endemic lyssaviruses, a group of globally important zoonotic viral pathogens that continue to threaten human health (Fraser et al., 1996). Capable of causing fatal acute rabies-like encephalitis in humans, ABLV has since been a cause of considerable concern to wildlife, veterinary, and health-care workers. There are two genetically distinct variants of ABLV, one which circulates in frugivorous bats (suborder Megachiroptera, genus Pteropus (ABLVp)) and the other in the insectivorous yellow-bellied sheathtail microbat (suborder Microchiroptera, genus Saccolaimus) (ABLVs)) (Gould et al., 2002). While the prevalence of ABLV in healthy bats is estimated to be less than 1%, in sick or injured bats it may be as high as 20% in flying foxes, depending on the species, and up to 62.5% in the yellow-bellied sheathtail bat (Field, 2005). ABLV has caused three fatal human infections and each manifested as acute encephalitis; however, incubation periods were variable. The first fatal case occurred in November 1996 approximately 5 weeks after a 39-year-old female animal handler was bitten presumably by a yellow-bellied sheathtail bat (Allworth et al., 1996). A second fatal case was reported in November 1998, more than 2 years after a 37-year-old female was bitten by a flying fox (Hanna et al., 2000). The most recent case occurred in an 8-year old boy in February 2013, when he began to suffer convulsions, abdominal pain and fever, followed by progressive brain problems and coma. He died approximately 8 weeks after he was bitten (Anonymous, 2013a).

ABLV is a member of the family Rhabdoviridae, genus Lyssavirus. The Lyssavirus genus is divided into 12 classified species (http://www.ictvonline.org/virusTaxonomy.asp; accessed 02 May 2013) and three recently described bat lyssaviruses not yet classified (Ceballos, 2013); all species are capable of causing fatal neurological disease indistinguishable from clinical rabies in humans and other mammals. Except for Mokola virus, all lyssavirus species have known bat reservoirs, leading to the speculation that lyssaviruses originated in bats (Badrane and Tordo, 2001). Of the lyssavirus species, ABLV is most closely related to classical rabies virus (RABV) (Gould et al., 2002). Lyssaviruses are enveloped, bullet-shaped viruses with a single-stranded, negative sense RNA genome that encodes five viral proteins: nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix (M), glycoprotein (G), and RNA polymerase (L). The G proteins associate into trimers on the virion surface and mediate viral attachment to and fusion with the host cell membrane (Gaudin et al., 1992). Following host cell attachment, lyssaviruses are internalized by means of receptor-mediated endocytosis; the low pH of the endosome triggers G-mediated fusion of the viral and host cell membranes.

Studies aimed at identifying host factors required for lyssavirus entry have thus far been limited to RABV. Lyssaviruses are highly neurotropic in vivo, but can replicate at sites of inoculation such as muscle tissue and epithelial cells (Burrage et al., 1985; Morimoto et al., 1996) and do exhibit a broad in vitro tropism (Tuffereau et al., 1998). For RABV, several host cell molecules have been proposed as receptors, but none have been shown to be essential in vitro. These include protein receptors such as nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) (Hanham et al., 1993; Lentz et al., 1982; Lentz et al., 1984), neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) (Thoulouze et al., 1998), and p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) (Tuffereau et al., 1998), as well as neuraminic acid containing glycolipids (gangliosides) (Conti et al., 1986; Superti et al., 1986). The nAchR, predominantly located in muscle cells, is not required for RABV infection of neurons (McGehee and Role, 1995), but may account for replication of RABV in myotubes at the site of inoculation (Burrage et al., 1985). The p75NTR does not interact with the majority of lyssavirus glycoproteins, including ABLV G (Tuffereau et al., 2001), and is not essential for RABV infection (Tuffereau et al., 2007). Similarly, although NCAM has been shown to be an in vitro receptor for a fixed strain of RABV, NCAM knock-out mice were still susceptible to RABV infection, although the disease was delayed by a few days (Thoulouze et al., 1998). The nature of the ABLV receptor(s) has not been investigated.

In contrast to RABV which has both bat and terrestrial mammal reservoirs, only bats are known reservoirs for ABLV. ABLV has been isolated from five bat species including all four common species of flying fox present in mainland Australia (Pteropus alecto, P. poliocephalus, P. scapulatus and P. conspicullatus) and the insectivorous microbat Saccolaimus flaviventris; however, it is likely that all Australian bats may potentially serve as host reservoirs of the virus (Hooper et al., 1997; McCall et al., 2000). The first ABLV spillover into a terrestrial species other than humans was recently reported in May of 2013, when two ill horses in Queensland tested positive for ABLV infection and were euthanized, and presently the infections are presumably caused by exposure to infected microbats (Anonymous, 2013b). The fatal human and recent equine infections clearly demonstrate that ABLV can infect other non-bat species. Furthermore, molecular evidence suggests that terrestrial RABV evolved from bat lyssaviruses (Badrane and Tordo, 2001). Although the risk of human exposure to ABLV is currently believed to be limited to contact with infected bats, the establishment of ABLV in terrestrial animal populations would significantly increase this risk. To understand the cross-species transmission potential of ABLV, infection tropism should be better defined. Characterization of ABLV tropism will also provide important data for ABLV receptor identification.

In the present study, we developed fluorescent protein-encoding recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses (rVSV) that express ABLV G envelope glycoproteins and have used them to examine ABLV entry and infectivity as a function of G. Target cell lines derived from numerous mammalian species were permissive to ABLV, indicating that the ABLV host cell receptor(s) is broadly conserved. Notably, the two ABLV variants exhibited distinct in vitro tropisms, suggesting that they can utilize alternate host factors for entry. Also, cell lines resistant to ABLV G-mediated infection were identified, and these also expressed proposed RABV receptors, indicating that a receptor(s) required for ABLV host cell entry remains to be identified.

Results and Discussion

In vitro tropism of ABLV-G mediated viral entry

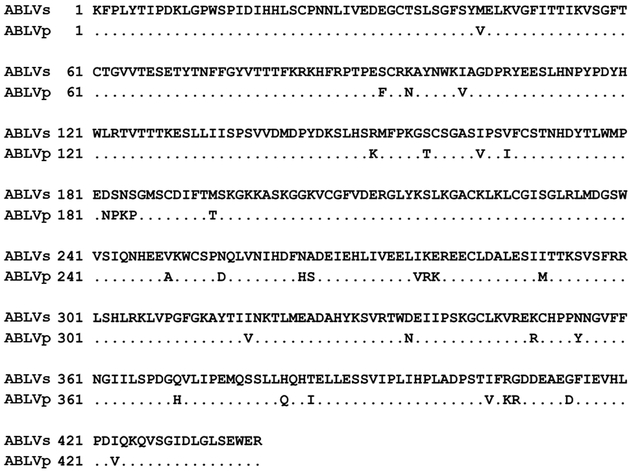

The Saccolaimus and Pteropus ABLV variant G proteins are highly homologous, sharing 92% amino acid identity within the G ectodomain (Fig. 1). However, because a single amino acid change within a viral glycoprotein can alter cellular tropism (Tuffereau et al., 1989; Vahlenkamp et al., 1997), it is very possible that ABLVs and ABLVp, which differ by 33 amino acids within the G ectodomains, exhibit distinct tropisms. The very different incubation periods of human infections caused by the two variants, as well as the lack of overlapping host reservoir species, also point to possible tropism differences between ABLVs and ABLVp. To investigate ABLV tropism we developed and recovered maxGFP-encoding replication competent recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses (rVSV) that express the G proteins from both ABLVs and ABLVp and used them as infection screening tools to examine infectivity and tropism, as a function of ABLV G. This approach has several advantages over using WT ABLV. First, rVSV-ABLV G viruses are safer and easier to manipulate than WT ABLV. Second, the incorporation of GFP into the viral genome eliminates the need for traditional fluorescent antibody staining to detect infected cells. Third, the inclusion of rVSV-VSV G as a positive control in all infection assays enables us to distinguish between actual ABLV G entry blocks and post-entry VSV inhibition. Previous studies that examined in vitro RABV tropism and receptor usage did not control for post-entry inhibition (Thoulouze et al., 1998; Tuffereau et al., 1998). Furthermore, because the viral backbones of the rVSV reporter viruses are identical except for the envelope glycoproteins, the tropism differences exhibited by the different viruses can be attributed directly to differences among the G proteins themselves.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of Saccolaimus and Pteropus ABLV G mature protein ectodomains. Scoring matrix: BLOSUM62.

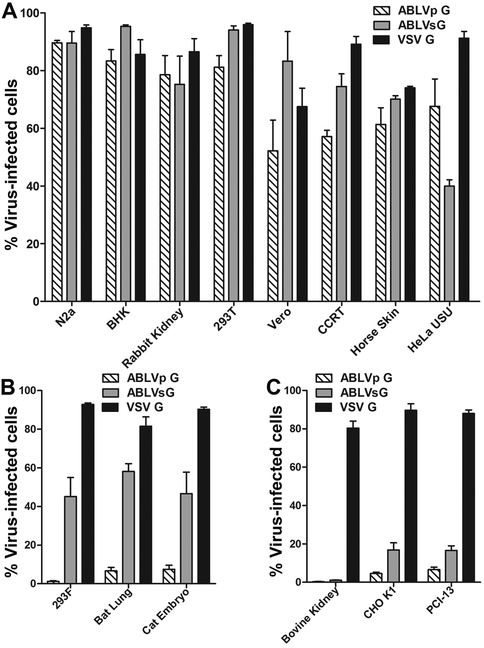

Diverse target cell populations were infected with the rVSV-maxGFP viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 and the percent of maxGFP positive cells, indicative of productive infection, was determined 18–20 hrs post infection. As shown in Fig. 2A, several target cell lines derived from both neuronal and non-neuronal tissues of numerous mammalian species, including multiple species of small rodents, rabbit, human, monkey, and horse, were permissive to viral entry mediated by the G proteins of both ABLV variants. This is in agreement with the broad in vitro tropism reported for RABV (Thoulouze et al., 1998). To date, except for the three human infections and the two recent equine cases, there have been no confirmed reports of ABLV infection in other terrestrial mammals despite known contacts of domestic dogs with infected bats (McCall et al., 2005). Dogs and cats experimentally infected with a laboratory adapted strain of ABLVp exhibited mild behavioral changes and seroconverted within the three month study, but none succumbed to ABLV and no viral antigen was detected at necropsy (McColl et al., 2007). However, this study was only carried out for three months and it is possible that this was not sufficient time for the virus to reach the brain; the single documented human ABLVp infection had an incubation period of more than two years (Hanna et al., 2000). The ability of ABLVs to cause clinical disease in dogs and cats has not been evaluated. Nevertheless, the tropism data described here indicates that the ABLV receptor(s) is highly conserved among mammals and suggests that species other than bats, humans, and horses could potentially be susceptible to ABLV infection.

Fig. 2.

ABLV in vitro entry tropism. (A-C) Target cells infected with recombinant VSV-maxGFP reporter viruses at a MOI=1 were harvested 18–20 hrs post infection and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. GFP expression, indicative of productive infection, was analyzed by flow cytometry. The percent of virus-infected cells was calculated by dividing the number of GFP positive cells by the total number of cells in the parent population. (A) Numerous mammalian cell lines are permissive to ABLV G-mediated host cell entry. (B) Saccolaimus and Pteropus ABLV variants display unique in vitro entry tropisms. (C) Low ABLV infectivity of resistant cell lines is not due to post-entry VSV inhibition. Data are the means from 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Reporter viruses that express VSV G were included as a positive control. N2a, mouse neuroblastoma; BHK, baby hamster kidney; 293T and 293F, human embryonic kidney; Vero, African green monkey kidney; CCRT, cotton rat osteogenic sarcoma; HeLa USU, human cervical adenocarcinoma; CHO K1, Chinese hamster ovary; PCI-13, human head and neck sarcoma.

Interestingly, we also identified three cell lines derived from human (293F), insectivorous bat, and cat embryonic tissues that exhibited a 6–45 fold difference in infectivity mediated by the G proteins of ABLVs and ABLVp (Fig. 2B). All three cell lines were moderately permissive to ABLVs G-mediated (> 45% total cells infected), but resistant to ABLVp G-mediated viral entry (< 10% total cells infected), suggesting that ABLV variants can utilize alternate host factors for entry. It was surprising that the 293F cells, which are a derivative of HEK293 cells that have been adapted for growth in serum-free medium as suspension cells, were resistant to ABLVp (< 5% total cells infected) (Fig. 2B) given that adherent 293T cells are highly permissive to both ABLV variants (Fig. 2A). Dube et al. reported that 293F cells grown as adherent, rather than suspension cultures were significantly more susceptible to Ebola virus envelope glycoprotein GP pseudotyped virus infection (Dube et al., 2008). To determine whether a similar phenomenon may exist for ABLVp G-mediated viral entry, 293F cells were grown in serum-supplemented medium to allow the cells to form adherent monolayers prior to infection with rVSV-ABLV G reporter viruses. As shown in Fig. 3A, although 293F cells grown in suspension were resistant to ABLVp G-mediated infection, cells grown as adherent monolayers were highly permissive to infection; thus, it appeared that cell adhesion promoted ABLVp infection. However, because adherent and suspension cultures of 293F cells were grown in the presence or absence of serum, respectively, it was possible that it was the addition of serum, rather than cell adhesion that promoted ABLVp infection of 293F cells. To address this, 293T cells kept in suspension by continuous rotation in microcentrifuge tubes were infected with rVSV-ABLVp G in the presence or absence of serum in several commercially available media. Reporter virus that expressed VSV G was included as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 3B, suspension cultures of 293T cells were highly permissive to ABLVp infection regardless of whether serum was present (DMEM-10) or not (DMEM-0, Gibco® 293 Freestyle™, OptiMEM®); only cells cultured in Gibco® 293 SFMII medium, the standard culture medium used for 293F cell maintenance, were resistant to ABLVp G-mediated viral infection. VSV G-mediated infection was not inhibited, demonstrating that the antiviral component within 293 SFMII medium blocks ABLVp G-mediated infection at the level of entry.

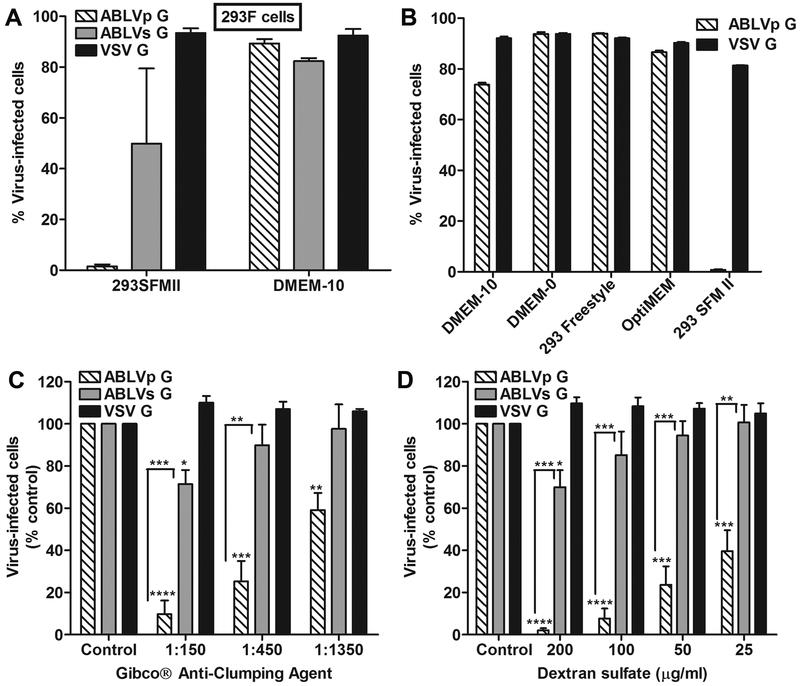

Fig. 3.

Anti-clumping agents are potent inhibitors of entry mediated by Pteropus, but not Saccolaimus ABLV G. (A-D) Cells were infected and analyzed as described in Fig. 2. (A) HEK 293F cells grown in Gibco® 293 SFMII serum-free medium (suspension cells), but not serum supplemented DMEM (adherent cells), are resistant to ABLVp G-mediated infection. (B) Inhibition of ABLVp infection of suspension cultures of 293T is restricted to cells grown in 293 SFMII medium. 293T cells (5×105) in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes were pelleted by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 5 min. Cells were washed once with PBS, pelleted, and then were resuspended in 500 ml of culture medium as designated. (C) Proprietary Gibco® anti-clumping agent in 293 SFMII medium inhibits ABLVp G-mediated entry into 293T cells. (D) Low molecular weight dextran sulfate (5 kDa) is a potent inhibitor of ABLVp G-mediated viral entry into 293T cells. 293T monolayers were washed once with PBS prior to addition of culture medium supplemented with 3-fold dilutions of Gibco® anti-clumping agent beginning at 1:150 (C) or with 2-fold serial dilutions of low molecular weight dextran sulfate (5kDa) beginning with 200 µg/ml (D). Results are expressed as percent virus-infected cells relative to that of untreated controls. Data represent three independent experiments and error bars represent SEM. ****, p< 0.0005; ***, p< 0.005; **, p< 0.01; *, p< 0.05.

Low molecular weight dextran sulfate is a potent inhibitor of viral entry mediated by ABLVp G, but not ABLVs G

The complete formulations of 293 SFMII and OptiMEM® serum-free media, which inhibits and supports ABLVp infection, respectively, are not publicly available. However, the manufacturer acknowledged that 293 SFMII medium contains a proprietary anti-clumping reagent that is not present in OptiMEM®. To determine whether the anti-clumping agent was responsible for the ABLVp G-mediated viral inhibition, 293T cell culture medium was supplemented with Gibco® anti-clumping agent prior to infection with rVSV reporter viruses. As shown in Fig. 3C, the anti-clumping agent significantly inhibited ABLVp G-mediated infection in a dose-dependent manner. Although ABLVs G-mediated infection was significantly reduced at the lowest dilution of anti-clumping agent tested, only 20–30% inhibition was observed compared to >80% inhibition of ABLVp infection relative to untreated controls. As expected, the agent had no effect on VSV G-mediated infection.

Low molecular weight dextran sulfate (5 kDa) is a conventional anti-clumping agent that has been used by the manufacturer of 293 SFMII in past serum-free media formulations (Gorfien, 2004). To determine whether dextran sulfate inhibited ABLVp G-mediated viral infection, culture medium supplemented with 2-fold serial dilutions of 5 kDa molecular weight dextran sulfate was added to 293T cell monolayers prior to infection with rVSV reporter viruses. Results paralleled what was seen with the anti-clumping agent: dextran sulfate reduced ABLVp G-mediated infection by up to 97% in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3D). At the highest dose, ABLVs G-mediated infection was significantly inhibited but the percent of inhibition was significantly lower than that observed for ABLVp at the same dose (20–30% versus 97%, respectively). ABLVs was not inhibited at lower concentrations of dextran sulfate and VSV was not inhibited at the concentrations tested. Dextran sulfate has been reported to have antiviral activity against numerous enveloped RNA and DNA viruses; the mechanism of antiviral action is thought to be mediated by a direct interaction of dextran sulfate with the viral envelope glycoproteins (Witvrouw and De Clercq, 1997). In contrast to previous studies which reported a potent antiviral effect of dextran sulfate on VSV (Baba et al., 1988; Luscher-Mattli et al., 1993; Witvrouw and De Clercq, 1997), in our experiments VSV entry was not inhibited at any concentration of dextran sulfate tested (Fig. 3D). However, the aforementioned studies used higher molecular weight dextran sulfate and different cell lines, which may account for the different experimental outcomes. The potent inhibition of ABLVp G-, but not of ABLVs G-mediated viral entry by dextran sulfate strengthens the argument that the two ABLV variants can exploit alternate receptors to gain entry into host cells.

Low ABLV infectivity of resistant cell lines is not due to post-entry VSV inhibition or lack of host cell attachment

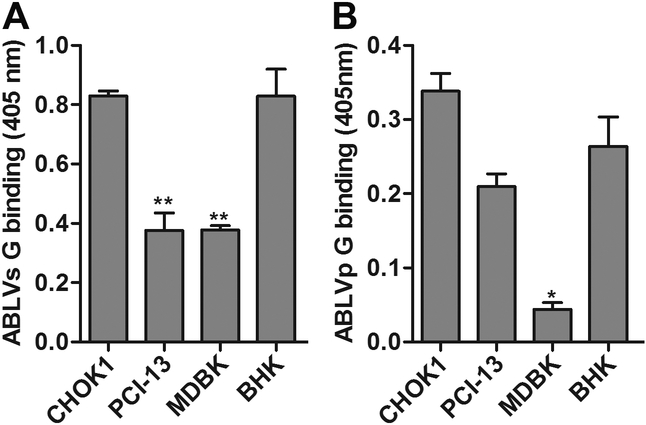

Cell lines that were resistant to ABLV G-mediated infection, with only 1–20% of total cells infected after 20 hrs, were also identified in our in vitro tropism studies (Fig. 2C). These included bovine kidney (MDBK), CHOK1, and a human head and neck sarcoma cell line (PCI-13). VSV G expressing control viruses infected greater than 80% of these cells, indicating that the low ABLV infectivity was not due to post-entry VSV inhibition. To examine whether the lower susceptibilities corresponded to decreased viral binding, paraformaldehyde fixed monolayers of cells were incubated for 1 hr at 37°C with rVSV-ABLV viruses (MOI=20). Bound ABLV virus was detected by cell ELISA with anti-ABLV G sera (see Materials and Methods). BHK cells were included as positive controls for viral binding. Although there was significantly (p< 0.01) less binding of ABLVs G to PCI-13 and MDBK cells than BHK cells, ABLVs G was able to bind to all three resistant cell lines and binding to CHOK1 was similar to permissive BHK cells (Fig. 4A). Likewise, binding of ABLVp G to MDBK cells was significantly (p< 0.03) less than BHK cells; however, ABLVp G bound to CHOK1, PCI-13, and BHK cells equally (Fig. 4B). Thus, with the possible exception of ABLVp G-mediated infection of MDBK cells, the decreased susceptibility of CHOK1, PCI-13, and MDBK cells to ABLV G-mediated viral infection was not due to lack of host cell attachment, suggesting that host cell entry of ABLV may require interaction with two or more co-receptors. Dual- or multi-receptor models have been proposed for a number of viruses (Sieczkarski and Whittaker, 2005) as well as the highly neurotropic botulinum and tetanus toxins (Popoff and Poulain, 2010).

Fig. 4.

ABLV entry block in resistant cells is not due to lack of host cell attachment. (A) ABLVs G binding. (B) ABLVp G binding. Cell monolayers fixed with 2% PFA were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS and incubated with rVSV virus (5×106 IU) for 1 hr at 37°C. For detection of bound virus, cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with either rabbit or mouse anti-ABLVs Gs polyclonal serum (see Materials and Methods), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hr at 37°C. Reactions were developed with ABTS substrate for 30 min at room temperature and absorbance was measured at 405 nm. The average value was calculated from duplicates. Background absorbance, determined by incubation of target cells with primary and secondary antibodies only, was subtracted from plotted data. Data represent the mean of two independent experiments and error bars represent SEM. BHK cells were included as a positive control. **, p<0.01; *, p<0.03.

ABLV and rabies virus require alternate host factors for entry

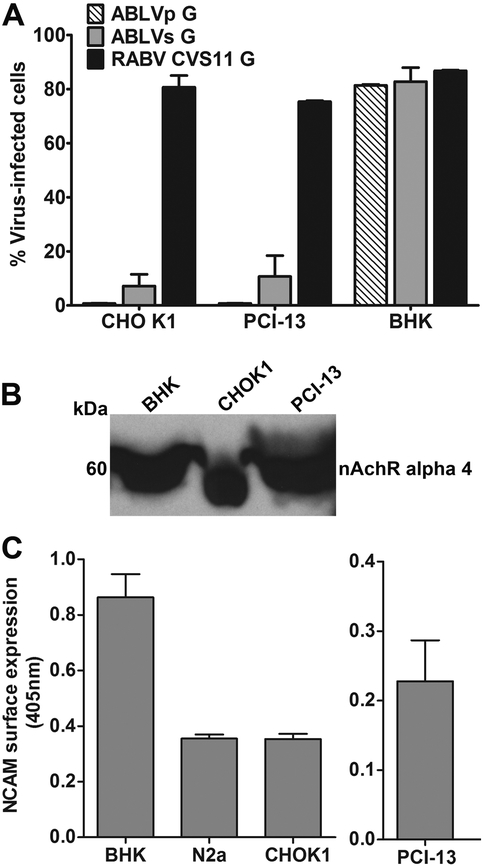

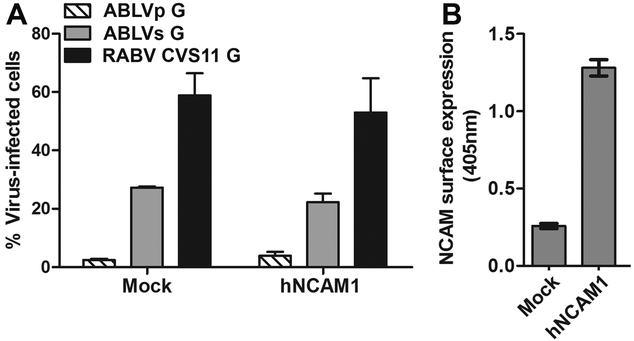

The identification of CHOK1 cells as an ABLV resistant cell line was particularly interesting as these cells have been reported to be highly permissive to the CVS-11 fixed strain of RABV (Thoulouze et al., 1998), suggesting that ABLV and RABV may utilize alternate receptors for host cell entry. To confirm this possible in vitro tropism difference between ABLV and RAeBV, we rescued a recombinant VSV reporter virus that encodes the CVS-11 G protein and tested the ability of this virus to mediate entry into ABLV resistant CHOK1 and PCI-13 cells. BHK cells were included as a positive control. CHOK1 and PCI-13 cells were highly permissive to VSV-RABV CVS11 G infection, with 70–80% of total cells infected after 20 hrs (Fig. 5A). Expression of the proposed RABV protein receptors nAchR (Fig. 5B) and NCAM (Fig. 5C) was confirmed in both cell lines. Although NCAM surface expression on CHOK1 cells was approximately 2-fold less than that on ABLV permissive BHK cells, the CHOK1 NCAM levels were similar to those on mouse neuroblastoma cells (N2a) (Fig. 5C), which are highly permissive to both ABLV (Fig. 2A) and RABV infection (Thoulouze et al., 1998). However, to verify that the low ABLV infectivity of CHOK1 cells was not due to low expression of NCAM, a human NCAM (hNCAM) cDNA clone was transfected into CHOK1 cells. Over-expression of hNCAM was not sufficient to allow ABLV G proteins to mediate viral entry into transfected CHOK1 cells (Fig. 6A). This was not due to lack of hNCAM expression in transfected cells (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, HeLa-USU cells, which do not express NCAM on the cell surface (data not shown), are permissive to ABLV G-mediated infection (Fig. 2A). Taken together, these results indicate that the proposed RABV receptors nAchR and NCAM are not sufficient to allow host cell entry of ABLV. Rather, ABLV appears to utilize a receptor(s) for host cell entry that has yet to be identified.

Fig. 5.

ABLV resistant cells express proposed rabies virus receptors. (A) ABLV resistant cell lines are highly permissive to rabies virus G-mediated viral entry. Cells were infected as described in Fig. 2. GFP positive cells were counted with a Nexcelom Vision automated cell counter with fluorescence detection and the percent of virus-infected cells was calculated by dividing the number of GFP positive cells by the total number of cells counted. Data represent the mean of two independent experiments and error bars represent SEM. (B) Endogenous nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAchR) expression. Cell lysates were prepared in buffer containing Triton X-100, clarified by centrifugation and analyzed by 4–12% BT SDS PAGE. An equivalent of 1×106 cells per well were analyzed as described in the methods. nAchR was detected by Western blotting with rabbit anti-nAchR alpha 4 polyclonal antibody. BHK cells were included as a positive control. (C) Endogenous surface expression of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM). Cell monolayers fixed with 2% PFA were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS and then incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-NCAM mAbs (3 µg/ml) specific for mouse (BHK, N2a and CHOK1) or human (PCI-13) NCAM. Following incubation with HRP conjugated anti-mouse IgG for 1 hr at 37°C, reactions were developed with ABTS substrate for 30 min at room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm and the average value was calculated from duplicates. Incubation of target cells with secondary antibody only was used to determine background absorbance and was subtracted from plotted data. Data represent at least two independent experiments and error bars represent SEM. BHK and N2a cells were included as a positive control.

Fig. 6.

The rabies virus receptor neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) is not a receptor for ABLV. (A) Over-expression of human NCAM1 (hNCAM1) does not render CHOK1 cells permissive to ABLV. CHOK1 cells transfected with an hNCAM1 cDNA clone (see Materials and Methods) were infected 24 hrs post-transfection and analyzed as described in Fig. 5A. Results shown are the mean from 2 independent experiments and error bars represent standard error of the mean. (B) Human NCAM1 surface expression in hNCAM-transfected CHOK1 cells. Mock and hNCAM -transfected cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde 24 hrs post-transfection. A mouse anti-human NCAM mAb was used to detect NCAM expression by cell ELISA as described in Materials and Methods.

Disruption of lipid rafts significantly reduces ABLV G-mediated viral entry into 239T cells

The observation that proposed RABV receptors are not sufficient to allow ABLV G to mediate viral entry into host cells prompted an examination of the nature of the unknown ABLV receptor(s). We treated permissive target cells with increasing doses of neuraminidase or protease (pronase, proteinase K, and trypsin) and in no case was ABLV G-mediated entry inhibited (data not shown). One possible explanation for these results could be that ABLV G interacts with more than one host cell receptor for entry, as is suggested by the ability of rVSV-ABLV G viruses to bind to cells resistant to infection (Fig. 4). If the co-receptors belong to different classes of macromolecules, as is the case for several bacterial neurotoxins which utilize glycolipid and protein co-receptors to enter neurons (Popoff and Poulain, 2010), then treatment with protease or neuraminidase alone would not reduce viral infection; surface bound virions would interact with functional co-receptors as soon as the enzyme cleaved receptors were recycled and replaced by native ones. Thus, protein or sialic acid moieties as the ABLV receptor(s) cannot be ruled out.

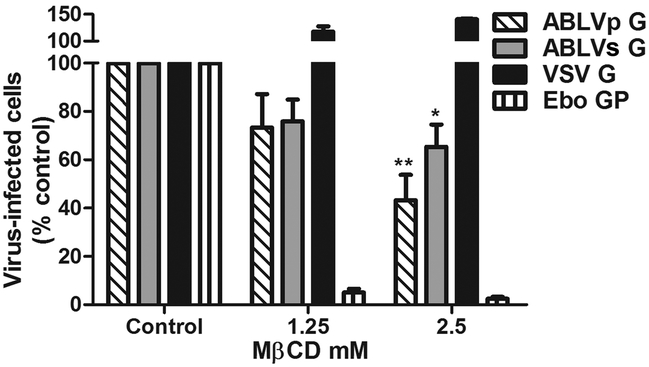

We next examined whether lipid raft integrity was important for ABLV G-mediated viral entry. To disrupt lipid rafts, 293T cell monolayers were pre-treated with the cholesterol-sequestering drug methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) for 1 hr at 37°C. The drug was removed and the cells were washed extensively prior to rVSV infection. Subsequent to depletion of cholesterol with MβCD, culture medium was supplemented with menovalin (4 µg/ml) to prevent de novo cholesterol synthesis. VSV reporter viruses expressing VSV G, and Ebola virus GP (Ebo GP) were included as negative and positive controls, respectively. As previously reported, MβCD treatment caused a drastic reduction of Ebo GP-mediated infection (Saeed et al., 2010) but enhanced VSV G-mediated infection (up to 40%) (Fig. 7) (Shah et al., 2006). ABLV G-mediated infection was significantly reduced (57% and 35% inhibition for ABLVp and ABLVs, respectively) compared to untreated controls (Fig. 7), suggesting that the ABLV receptor(s) is localized or enriched in lipid rafts.

Fig. 7.

Disruption of lipid rafts significantly reduces ABLV G-mediated viral entry into 293T cells. 293T cell monolayers were treated with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) diluted in OptiMEM for 1 hr at 37°C. The drug was removed and the cells were washed three times with PBS to remove the drug. Cells were infected with rVSV (MOI=1) diluted in OptiMEM supplemented with 4 µg/ml mevinolin and analyzed as described in Fig. 5A. rVSV viruses encoding Ebo GP and VSV G were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, to assess MβCD activity. Results are expressed as percent virus-infected cells relative to that of untreated controls and represent three independent experiments; error bars are SEM. **, p<0.01; *, p<0.05.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed replication-competent rVSV maxGFP reporter viruses that encode ABLV G envelope glycoproteins and have used them to characterize ABLV entry tropism as a function of G. The results presented here provide the first in vitro tropism data for a lyssavirus species other than classical RABV and reveal that although ABLV and RABV are closely related and are capable of causing identical fatal neurological disease in humans, they display distinct in vitro tropisms and can utilize alternate host receptors for viral entry. The same is true for Saccolaimus and Pteropus variants of ABLV. The ABLV receptor(s) appears to be highly conserved among mammalian species and may localize to lipid rafts. A major obstacle to identifying specific host cell receptors required for RABV entry has been the ability of fixed strains of RABV to replicate in most continuous cell lines (Thoulouze et al., 1998; Tuffereau et al., 1998); thus, methods that have been successfully used to identify receptors for other viruses could not be used for RABV. Here however, we were able to identify several cell lines resistant to ABLV G-mediated viral entry. ABLV resistant CHOK1 cells in particular, which are easy to transfect with expression plasmids, will be an invaluable tool for future studies aimed at ABLV receptor identification.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The following cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC): N2a (mouse neuroblastoma) (CCL-131); BHK (CCL-10); RK-13 (rabbit) (CCL-37); Equus caballus (horse) (CCL-57); Tadarida brasilliensis (bat) (CCL-88); MDBK (CCL-22); CHO-K1 (CCL-61). 293T cells were provided by Gerald Quinnan (Uniformed Services University). Cat embryo, HeLa-USU, PCI 13, and CCRT cell lines have been described (Blanco et al., 2009; Bonaparte et al., 2005; Bossart et al., 2001). Vero cells were provided by Alison O’Brien (Uniformed Services University). 293F cells were purchased from Invitrogen Corp (Carlsbad, CA). N2a, BHK, MDBK, CHO-K1, 293T, HeLa-USU, Vero, and CCRT cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Quality Biologicals, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum (CCS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 2 mM L-glutamine (DMEM-10). PCI-13 cells were maintained in DMEM-10 supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (Quality Biologicals). Rabbit and horse cells were maintained in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM) (Quality Biologicals) supplemented with10% CCS, 2 mM L-glutamine (EMEM-10) supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Bat cells were maintained in EMEM-10 supplemented with 0.85 g/L sodium bicarbonate. Cat embryo cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Quality Biologicals) supplemented with 10% CCS and 2 mM L-glutamine (RPMI-10). 293F cells were maintained in 293SFMII (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine. All cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Reagents and antibodies

OptiMEM® culture medium, Gibco® Freestyle™ 293 expression medium, and Gibco® anti-clumping agent were purchased from Invitrogen. Dextran sulfate sodium salt (5kDa) methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) and mevinolin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions were prepared in water (dextran sulfate and MβCD) or DMSO (mevinolin) and stored, as per manufacturer’s recommendation. Polyclonal rabbit and mouse anti-sera against ABLV G were produced in mice and rabbits (Spring Valley Laboratories, Sykesville, MD). Goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG (H+L) horse radish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Pierce, Rockford, IL). Mouse MAbs specific for mouse (catalog no. 60211A) and human (catalog no. 559043) neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) were purchased from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA. Rabbit anti-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 polyclonal antibody [N1C1] (catalog no. GTX113653) was purchased from GeneTex Inc., Irvine, CA.

Plasmids

Full-length ABLV G cDNA sequences for both the Pteropus (ABLVp G) (GenBank accession AF426309.1) and Saccolaimus (ABLVs G) (GenBank accession AAN63540.1) variants (Guyatt et al., 2003) were codon optimized and synthesized by Geneart Inc., Germany and then cloned into the mammalian expression vector pCAGGS (Niwa et al., 1991). The Rabies virus strain CVS-11 G sequence (GenBank accession EU352767.1) was synthesized by GenScript USA Inc., Piscataway NJ, and then cloned into a promoter-modified pcDNA3.1 vector. Plasmids that encode the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), and RNA polymerase (L) genes and a full-length anti-genomic VSV Indiana cDNA clone that expresses Ebola Zaire virus glycoprotein GP and the fluorescent mCherry protein were kindly provided by Paul Bates (University of Pennsylvania). Recombinant VSV reporter plasmids that express maxGFP (Lonza Inc., Allendale, NJ) were constructed by replacing the mCherry gene, in the full-length anti-genomic VSV Indiana cDNA clone, with that for maxGFP. To construct full-length VSV-ABLV G- reporter plasmids, standard cloning techniques were used to replace the Ebola GP gene with ABLVs G and ABLVp G genes. VSV-GFP reporter plasmids that express Rabies CVS11 G and native VSV G (Indiana) were similarly constructed. All VSV-GFP reporter plasmids were then used to rescue replication competent recombinant VSV reporter viruses. An open reading frame (ORF) clone of the human neural cell adhesion molecule 1 (phNCAM1), transcript variant 2 (catalog no. RC207890) was purchased from OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD.

Recovery, purification and titration of rVSV

Recombinant reporter viruses were recovered using reverse genetics (Lawson et al., 1995) with some modifications. HEK293T cells grown to 70–80% confluence in 6-well culture plates were transfected with plasmids encoding the recombinant VSV antigenomic RNA (2.5 µg) and the VSV N (2.5 µg), P (2.5 µg), and L (0.5 µg) genes under control of the bacteriophage T7 promoter using the Lipofectamine LTX transfection reagent. After 4–5 hrs, the transfection mix was removed and cells were infected with MVA-T7 (Sutter et al., 1995) at a multiplicity of infection of 1. After 1 hr, the viral inoculum was removed, cells were washed 3 times with PBS, and fresh medium was added to the wells. After 48 hrs incubation at 37°C, cells and supernatants were collected and subjected to three rounds of freeze-thawing (−80°C, 37°C) to release cell-associated virus. Cell debris was pelleted from the lysates by centrifugation for 5 min at 1300 × g. The clarified lysate was slowly filtered through a 0.22 µm filter to remove the MVA-T7. Five hundred microliters of the lysate was then added to ~ 2×106 293T cells on a 6-well plate in 1.5 ml of DMEM-10. After 48 hrs, cells were observed for fluorescent reporter gene expression and CPE by microscopy (10X objective).

To prepare viral stocks, 293T cells in T-162 flasks were infected with the rVSV virus and supernatants were collected 24–48 hrs later. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 2600 rpm for 10 min. Clarified supernatant was layered on top of 20% sucrose in TNE buffer (10 mM Tris, 135 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA) and centrifuged at 27,000 rpm for 2 hrs. Virus pellets were resuspended in 10% sucrose/TNE buffer. Viral titers were determined by adding serial 10-fold dilutions of virus to 293T cells grown on 96-well plates. At 24 hrs post-infection, fluorescent cells were counted under a fluorescent microscope and calculated as infectious units/ml (IU/ml).

Cell infection assays

Target cells were infected with rVSV-GFP virus at a MOI=1. 18–20 hrs post-infection, cells were harvested and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA). GFP expression, indicative of productive infection, was analyzed by either flow cytometry or a Nexcelom Vision cellometer (Nexcelom Bioscience LLC., Lawrence, MA) capable of fluorescence detection. The percent of infected cells was calculated by dividing the number of GFP positive cells by the total number of cells in the parent population and multiplying by 100. To determine the effect of anti-clumping agents on ABLV G-mediated infection, cells were treated with Gibco® anti-clumping agent (3-fold dilutions beginning at 1:150) or low molecular weight dextran sulfate (5kDa) (2-fold dilutions beginning at 200 ug/ml) diluted in OptiMEM serum free medium (Invitrogen). To determine whether cholesterol enriched lipid raft domains are important for ABLV entry, 293T cell monolayers were treated with the cholesterol sequestering drug methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) diluted in OptiMEM for 1 hr at 37°C. Cells were then washed three times with PBS to remove the drug and infected with rVSV (MOI=1) diluted in OptiMEM supplemented with 4 µg/ml mevinolin to prevent de novo synthesis of cholesterol. Pilot experiments indicated that 10 mM MβCD appeared toxic and cells detached from the culture plates; cells treated with 5 mM MβCD initially looked healthy, but cell viability was drastically reduced by the end of the experiment. In the final experiments 2.5 mM MβCD was used. To assess MβCD activity, rVSV viruses encoding Ebo GP and VSV G were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. In all drug treatment experiments, results are expressed as percent virus-infected cells relative to that of untreated controls

Virus binding assay

Target cells (2×105) grown in 8-well chamber slides were washed once with cold PBS, and then fixed with 2% PFA for 30 min at room temperature. Fixed cell monolayers were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS (BSA/PBS) for 1 hr at 37°C and then incubated with rVSV virus (5×106 IU) diluted in 200 µl BSA/PBS for 1 hr at 37°C. After washing with PBS (3X) cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-ABLVs Gs polyclonal serum (1:10,000) to detect bound VSV-ABLVs G virus or with mouse anti-ABLVs Gs polyclonal serum (1:2000) to detect bound VSV-ABLVp G virus. Cells were washed with PBS (3X) and then incubated 1 hr at 37°C with either goat anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugated antibodies (1:10,000) diluted in 200 µl BSA/PBS. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated with 200 µl of ABTS [2,2´-azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)] substrate (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 30 min at room temperature. The developed substrate (100 µl) was transferred to a 96 well plate and absorbance was measured for each well at 405 nm, and the average value was calculated from duplicates. Target cells incubated with primary and secondary antibodies in the absence of virus were used as background controls.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were prepared by treatment with lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1X complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)). 5×106 cells of each population were lysed in 100 µl of lysis buffer and 20 µl of prepared lysate was loaded per well (an equivalent of 1×106 cells/well). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13,200 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and analyzed by 4–12% Bis-Tris SDS PAGE (Invitrogen) under reducing conditions (2% β-mercaptoethanol in NuPAGE sample buffer). Following transfer to nitrocellulose paper, the blot was probed with rabbit anti-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 polyclonal antibody (1:1000), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:20,000).

Cell ELISA to detect NCAM surface expression

Cell monolayers grown in 24-well plates were washed once with cold PBS, and then fixed with 2% PFA for 30 min at room temperature. Fixed cell monolayers were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS (BSA/PBS) for at least 1 hr at 37°C and then incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-NCAM mAbs (3 µg/ml) diluted in 250 µl BSA/PBS. Cells were washed three times with PBS and then incubated 1 hr at 37°C with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000) diluted in 250 µl BSA/PBS. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated with 300 µl of ABTS substrate for 30 min at room temperature. The developed substrate (100 µl) was transferred to a 96 well plate and absorbance was measured for each well at 405 nm, and the average value was calculated from duplicates. Target cells incubated with secondary antibody alone were used as background controls.

Expression of human NCAM1 in CHOK1 cells

CHOK1 cells were grown overnight to 60–80% confluence in 24 well culture plates. Cells were transfected with 0.5 µg of phNCAM1 plasmid or empty vector (mock) (8 wells each) using the Lipofectamine LTX transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Twenty four hours post-transfection, cells were infected in duplicate with rVSV virus and analyzed as described above. Expression of hNCAM1 was assessed 24 hrs post transfection by cell ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was used to evaluate the statistical significance levels of the data, with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ross Lunt at CSIRO Livestock Industries, Australian Animal Health Laboratory for providing the Saccolaimus and Pteropus bat brain tissues used for the initial cloning of Saccolaimus- and Pteropus-derived ABLV G and Dr. Paul Bates at the University of Pennsylvania for kindly providing the VSV full-length and helper plasmids. This work was supported by NIH grant AI057168 to C.C.B.

References

- Allworth A, Murray K, Morgan J, 1996. A human case of encephalitis due to a lyssavirus recently identified in fruit bats. Commun. Dis. Intellig 20, 504. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous, 2013a. Australian bat lyssavirus - Australia (02): Queensland, human fatality. Pro-MED-mail, International Society for Infectious Diseases: March 21, archive no. 20130323.1600266. Available at www.promedmail.org.

- Anonymous, 2013b. Australian Bat Lyssavirus - Australia (05): (Queensland) Equine, Fatal. Pro-MED-mail, International Society for Infectious Diseases: May 20, archive no. 20130520.1724384. Available at www.promedmail.org.

- Baba M, Snoeck R, Pauwels R, de Clercq E, 1988. Sulfated polysaccharides are potent and selective inhibitors of various enveloped viruses, including herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 32, 1742–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrane H, Tordo N, 2001. Host switching in Lyssavirus history from the Chiroptera to the Carnivora orders. J Virol 75, 8096–8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco JC, Pletneva LM, Wieczorek L, Khetawat D, Stantchev TS, Broder CC, Polonis VR, Prince GA, 2009. Expression of Human CD4 and chemokine receptors in cotton rat cells confers permissiveness for productive HIV infection. Virol J 6, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaparte MI, Dimitrov AS, Bossart KN, Crameri G, Mungall BA, Bishop KA, Choudhry V, Dimitrov DS, Wang LF, Eaton BT, Broder CC, 2005. Ephrin-B2 ligand is a functional receptor for Hendra virus and Nipah virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 10652–10657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossart KN, Wang LF, Eaton BT, Broder CC, 2001. Functional expression and membrane fusion tropism of the envelope glycoproteins of Hendra virus. Virology 290, 121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrage TG, Tignor GH, Smith AL, 1985. Rabies virus binding at neuromuscular junctions. Virus Res 2, 273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos NA, Moron SV, Berciano JM, Nicolas O, Lopez CA, Juste J, Nevado CR, Setien AA, and Echevarria JE, 2013. Novel Lyssavirus in Bat, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis 19, 793–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti C, Superti F, Tsiang H, 1986. Membrane carbohydrate requirement for rabies virus binding to chicken embryo related cells. Intervirology 26, 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube D, Schornberg KL, Stantchev TS, Bonaparte MI, Delos SE, Bouton AH, Broder CC, White JM, 2008. Cell adhesion promotes Ebola virus envelope glycoprotein-mediated binding and infection. J Virol 82, 7238–7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field HE, 2005. Australian bat lyssavirus, School of Veterinary Science. University of Queensland. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser GC, Hooper PT, Lunt RA, Gould AR, Gleeson LJ, Hyatt AD, Russell GM, Kattenbelt JA, 1996. Encephalitis caused by a Lyssavirus in fruit bats in Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 2, 327–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudin Y, Ruigrok RW, Tuffereau C, Knossow M, Flamand A, 1992. Rabies virus glycoprotein is a trimer. Virology 187, 627–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorfien SFU, Fike Richard M. (US), Dzimian Joyce L. (US), Godwin Glenn P. (US), Price Paul J. (US), Epstein David A. (US), Gruber Dale (US), Mcclure Don (US), 2004. Serum-free mammalian cell culture medium, and uses thereof. INVITROGEN CORP (US: ). [Google Scholar]

- Gould AR, Kattenbelt JA, Gumley SG, Lunt RA, 2002. Characterisation of an Australian bat lyssavirus variant isolated from an insectivorous bat. Virus Res 89, 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt KJ, Twin J, Davis P, Holmes EC, Smith GA, Smith IL, Mackenzie JS, Young PL, 2003. A molecular epidemiological study of Australian bat lyssavirus. J Gen Virol 84, 485–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanham CA, Zhao F, Tignor GH, 1993. Evidence from the anti-idiotypic network that the acetylcholine receptor is a rabies virus receptor. J Virol 67, 530–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna JN, Carney IK, Smith GA, Tannenberg AE, Deverill JE, Botha JA, Serafin IL, Harrower BJ, Fitzpatrick PF, Searle JW, 2000. Australian bat lyssavirus infection: a second human case, with a long incubation period. Med. J. Aust 172, 597–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper PT, Lunt RA, Gould AR, Samaratunga H, Hyatt AD, Gleeson LJ, Rodwell BJ, Rupprecht CE, Smith JS, Murray PK, 1997. A new lyssavirus: the first endemic rabies-related virus recognized in Australia. Bull. Inst. Pasteur 95, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson ND, Stillman EA, Whitt MA, Rose JK, 1995. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses from DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92, 4477–4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz TL, Burrage TG, Smith AL, Crick J, Tignor GH, 1982. Is the acetylcholine receptor a rabies virus receptor? Science 215, 182–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz TL, Wilson PT, Hawrot E, Speicher DW, 1984. Amino acid sequence similarity between rabies virus glycoprotein and snake venom curaremimetic neurotoxins. Science 226, 847–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher-Mattli M, Gluck R, Kempf C, Zanoni-Grassi M, 1993. A comparative study of the effect of dextran sulfate on the fusion and the in vitro replication of influenza A and B, Semliki Forest, vesicular stomatitis, rabies, Sendai, and mumps virus. Arch Virol 130, 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall BJ, Epstein JH, Neill AS, Heel K, Field H, Barrett J, Smith GA, Selvey LA, Rodwell B, Lunt R, 2000. Potential exposure to Australian bat lyssavirus, Queensland, 1996–1999. Emerg Infect Dis 6, 259–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall BJ, Field HE, Smith GA, Storie GJ, Harrower BJ, 2005. Defining the risk of human exposure to Australian bat lyssavirus through potential non-bat animal infection. Commun Dis Intell 29, 202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl KA, Chamberlain T, Lunt RA, Newberry KM, Westbury HA, 2007. Susceptibility of domestic dogs and cats to Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV). Vet Microbiol 123, 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Role LW, 1995. Physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by vertebrate neurons. Annu Rev Physiol 57, 521–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto K, Patel M, Corisdeo S, Hooper DC, Fu ZF, Rupprecht CE, Koprowski H, Dietzschold B, 1996. Characterization of a unique variant of bat rabies virus responsible for newly emerging human cases in North America. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 5653–5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J, 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108, 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoff MR, Poulain B, 2010. Bacterial toxins and the nervous system: neurotoxins and multipotential toxins interacting with neuronal cells. Toxins (Basel) 2, 683–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed MF, Kolokoltsov AA, Albrecht T, Davey RA, 2010. Cellular entry of ebola virus involves uptake by a macropinocytosis-like mechanism and subsequent trafficking through early and late endosomes. PLoS Pathog 6, e1001110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah WA, Peng H, Carbonetto S, 2006. Role of non-raft cholesterol in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection via alpha-dystroglycan. J Gen Virol 87, 673–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR, 2005. Viral entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 285, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Superti F, Hauttecoeur B, Morelec MJ, Goldoni P, Bizzini B, Tsiang H, 1986. Involvement of gangliosides in rabies virus infection. J Gen Virol 67 (Pt 1), 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter G, Ohlmann M, Erfle V, 1995. Non-replicating vaccinia vector efficiently expresses bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. FEBS Lett 371, 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoulouze MI, Lafage M, Schachner M, Hartmann U, Cremer H, Lafon M, 1998. The neural cell adhesion molecule is a receptor for rabies virus. J Virol 72, 7181–7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuffereau C, Benejean J, Blondel D, Kieffer B, Flamand A, 1998. Low-affinity nerve-growth factor receptor (P75NTR) can serve as a receptor for rabies virus. EMBO J 17, 7250–7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuffereau C, Desmezieres E, Benejean J, Jallet C, Flamand A, Tordo N, Perrin P, 2001. Interaction of lyssaviruses with the low-affinity nerve-growth factor receptor p75NTR. J Gen Virol 82, 2861–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuffereau C, Leblois H, Benejean J, Coulon P, Lafay F, Flamand A, 1989. Arginine or lysine in position 333 of ERA and CVS glycoprotein is necessary for rabies virulence in adult mice. Virology 172, 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuffereau C, Schmidt K, Langevin C, Lafay F, Dechant G, Koltzenburg M, 2007. The rabies virus glycoprotein receptor p75NTR is not essential for rabies virus infection. J Virol 81, 13622–13630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahlenkamp TW, Verschoor EJ, Schuurman NN, van Vliet AL, Horzinek MC, Egberink HF, de Ronde A, 1997. A single amino acid substitution in the transmembrane envelope glycoprotein of feline immunodeficiency virus alters cellular tropism. J Virol 71, 7132–7135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witvrouw M, De Clercq E, 1997. Sulfated polysaccharides extracted from sea algae as potential antiviral drugs. Gen Pharmacol 29, 497–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]