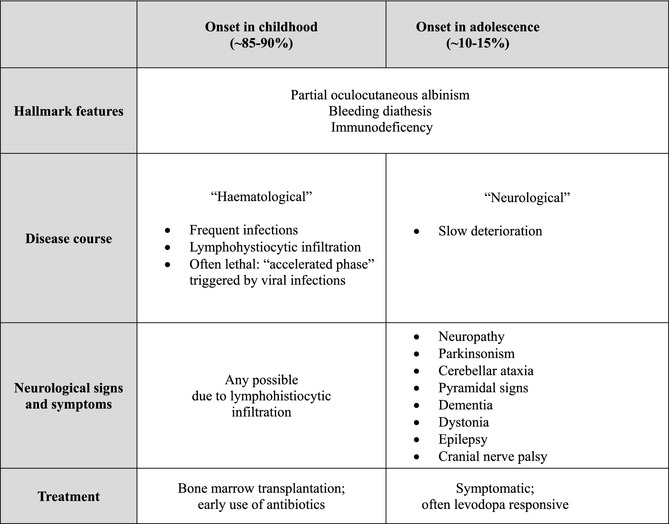

Chediak‐Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder resulting from mutations of the lysosomal trafficking regulator (LYST) gene.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Dysfunction of LYST leads to disruption of transport and fusion of lysosomes and similar organelles. This reflects in the characteristic features of (partial) albinism, if melanin is not transported to the keratinocytes; bleeding diathesis, as a result of impairment of the thrombocytic granula; and immunodeficiency, mainly because of a lack of perforin mediated cytotoxicity. The severity of symptoms varies greatly and depends on the remaining function of LYST (genotype‐phenotype correlation).6 Accordingly, the spectrum of CHS spans from childhood onset and a “mainly hematological,” potentially lethal disease course to the rarer variant of adulthood onset with slowly progressive neurodegeneration and only minor or no hematological disturbances (see Table 1). However, there is an overlap and the majority (~75%) of the cases with the later, neurological presentation do also featue immunodeficiency and/or bleeding diathesis.

Table 1.

Synopsis of the different presentations of CHS

Here, we present a case of CHS with juvenile onset of parkinsonism with video documentation of the typical features and review existing literature of movement disorder presentations of CHS. The review is based on a PubMed search for articles in English, Spanish, or German with the terms Chediak‐Higashi Syndrome, neurological, parkinsonism, tremor, ataxia, dystonia, myoclonus, tics, chorea, and a combination of these. Publications were included if sufficient evidence for a diagnosis of CHS (characteristic blood smear or gene mutation) was present; enough information of neurological status was provided; and when the neurological manifestation was not a result of lymphohistocytic infiltration.

Clinical History and Examination

This patient experienced progressive gait difficulties with falls as well as cognitive decline at age 20 years. It was also noted that he had become slower and quieter.

He had a normal birth, but slightly delayed milestones, and would start walking and talking considerably later than his older brother. He displayed hyperactive behavior and went first to a nursery and later to a school for handicapped children. His past medical history comprised a meningitis at age 7 as well as recurrent otitis media, tonsillitis, and sinusitis. He would bleed excessively after minor trauma. There was no family history.

Clinical examination at the age of 32 (as seen in the Video) reveals akinetic‐rigid parkinsonism with dementia, pyramidal signs, cerebellar ataxia, absent reflexes, and neuropathic foot deformities. Eye movements featured broken pursuit and slight slowing on both the horizontal and the vertical plane. There was but very mild albinism, noticeable only as a translucent iris, which became visible when testing for the pupillary reflexes.

Investigations and Treatment

Brain MRI was normal. Dopamine transporter (DaT) single‐photon emission CT (SPECT) showed decreased uptake bilaterally (reported previously7). Blood examination showed neutropenia and a prolonged bleeding time. In the blood smear, giant, peroxidase‐positive granules were detected within leucocytes. He responded very well to treatment with levodopa and dopamine agonists, but became eventually wheelchair bound and dependent in all activities of daily living during the 12 years since onset of his neurological deterioration.

Discussion and Literature Review

This patient presented with juvenile‐onset parkinsonism with dementia, pyramidal signs, cerebellar ataxia, and neuropathy; he also had a past medical history suggestive of minor immunodeficiency and bleeding diathesis as well as very mild albinism.

In keeping with recent literature, this case highlights that the “red flags” of associated features—albinism, bleeding diathesis, and immunodeficiency—may be mild or even absent in patients with the adult‐onset, “neurological” variant of CHS (nCHS). Hence, nCHS is perhaps underdiagnosed, and this notion is supported by recent evidence for a broadening of the phenotypic spectrum and the range of age at onset. First neurological signs usually occur in the early twenties, but age at onset is now recognized to be from the second up to the fifth decade.

A review of the existing literature of nCHS with focus on movement disorders is summarized in Table 2 and indicates that the two main presentations are that of parkinsonism, or cerebellar ataxia, mostly with additional neurological signs (see Table 2). Parkinsonism itself may be symmetric or asymmetric, akinetic‐rigid, or tremulous. Interestingly, preceding nonmotor features have also been described.8 Thus far, all reported cases had additional neurological findings, most frequently axonal neuropathy, and, to a lesser extent, pyramidal or cerebellar signs, cognitive impairment, and dystonia. Frequent oculogyric crises were reported in one patient and an upward gaze palsy in another (however, without clarification if this was indeed supranuclear).9, 10

Table 2.

Summary of the literature reporting movement disorders in the “neurological variant” of CHS

| Ref. | Age of onset Sex | Parkinsonism | Cerebellar ataxia | Neuropathy/reflex loss | Pyramidal involvement | Dystonia | Dementia | Other | Hypopigmentation/partial albinism (including iris translucency) | Immuno‐deficiency | Bleeding diathesis/thrombocytopenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 |

31 yr ♀ |

Symmetric, akinetic rigidNo response to l‐dopa | + | + | + | − | + | Learning difficulties; attention deficit | + | + | − |

|

Fourth decade ♂ |

Symmetric, tremulousl‐dopa responsive | + | + | − | − | + | Attention deficit | + | − | − | |

|

29 yr ♂ |

Asymmetric, tremulous |

− | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | ||

| 8 |

20 yr ♂ |

Symmetric, mainly akinetic‐rigid, impairment of postural reflexesNonmotor features: pain, fatigue, sleep disorderl‐dopa responsive | (+) | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | |

| 11 |

17 yr ♀ |

Symmetric, akinetic rigidPostural reflex lossl‐dopa responsive | − | + | − | + | + | Learning difficulties, behavioral problems | + | (+) | − |

| 12 |

21 yr ♂ |

Asymmetric, tremulousl‐dopa responsive | + | − | − | + | + | (+) | + | − | |

| 9 |

22 yr ♀ |

Symmetric, tremulousFreezing of gaitInitially l‐dopa responsive | − | + | + | + | + |

Speech difficulties; nystagmus Oculogyric crises |

+ | − | − |

| 7, 25 |

20 yr ♂ |

Symmetric, akinetic‐rigidl‐dopa responsive | + | + | + | − | + | Learning difficulties, hyperactive behavior | + | + | + |

| 17 |

19 yr ♂ |

Akinetic‐rigid with intermittent pill‐rolling tremor postural instabilityInitially l‐dopa responsive | + | + | + | − | − | Low IQ | − | + | − |

| 10 |

31 yr ♂ |

Not mentioned, but patient carried a diagnosis of postencephalitic parkinsonism | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | |

|

17 yr ♂ |

Not mentioned, but symmetric rest > intention tremor UL; tremor tongue, mandible | + | + | + | − |

Upward gaze palsy, CN IX palsy |

+ | nd | nd | ||

|

20 yr ♂ |

Not mentioned, but facial tremor, rest tremor UL |

+ | + | + | − | − | + | nd | nd | ||

| 18 |

Childhood ♂ |

− | + | + | + | − | Developmental delay; low IQ; epilepsy | + | + | + | |

|

Childhood ♀ |

− | + | + | − | − | − | Low IQ | + | + | + | |

| 26 |

Childhood ♂ |

− | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | nd | |

|

Childhood ♂ |

− | + | nd | − | − | − | Low IQ | + | + | nd | |

| 15 |

48 yr ♂ |

− | + | + | + | − | + | − | nd | nd | |

|

58 yr ♂ |

− | + | + | + | − | + | nd | nd | nd | ||

| 25 |

23 yr ♀ |

− | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | nd | |

| 14 |

22 yr ♂ |

− | + | + | − | − | − | Mental retardation | + | + | nd |

|

20 yr ♂ |

(−) (Bilateral hand tremor, unspecified; no parkinsonism mentioned) |

+ | + | − | − | − | + | + | nd | ||

|

24 yr ♀ |

(−) (Unspecified tremor; no parkinsonism mentioned) |

+ | + | − | − | − | Myoclonus | + | + | nd | |

| ∑ | Third decade (childhood–58 yr) | ~41–63% | ~81–86% | ~90–95% | ~59% | ~14% | ~41% | ~86–90% | ~72–78% | ~42% |

Response to l‐dopa was reported to be good in the majority of the cases, but may wear off.8, 9, 11, 12, 13 Other drugs found beneficial were amantadine and, less so, trihexyphenidyl.11, 12, 13 Of note, two parkinsonian patients featuring dystonia experienced a marked worsening of dystonia when treated with l‐dopa, which returned to baseline when stopping the medication.11, 12

MRI may be normal or reveal atrophy of the brain, cerebellum, or the spinal cord.8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 DaT‐SPECT of the patient described here, showing bilaterally decreased tracer uptake, has been reported previously.7

Thus, nCHS adds to the differential diagnosis of young‐onset parkinsonism. Oligosymptomatic nCHS may rarely mimic young‐onset Parkinson's disease related to PARKIN mutations where hyperreflexia, neuropathy, and dystonia may also be present, or dopa‐responsive dystonia.

More frequently, nCHS will feature a more widespread involvement and join the differential diagnosis of disorders with neuronal brain iron accumulation, Kufor Rakeb, Wilson's disease, manganese transporter deficiency, Huntington's disease, spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs), or hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs), and so on. Given that some patients present with a combination of parkinsonism, pyramidal signs, cerebellar ataxia, and dystonia, it could be also considered as a differential diagnosis of MSA; however, the so far reported nCHS patients with parkinsonism were considerably younger at onset than patients with MSA and did not feature autonomic signs. Thus, nCHS could also be included in the list of autosomal‐recessive ataxias or hereditary spastic paraplegias.

Other neurological manifestations include pure motor neuropathy, or neuropathy with pyramidal signs; sensorineuronal deafness; epilepsy, or cranial nerve palsies.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Mental retardation, developmental delay, or behavioral disturbances in early childhood can be part of the picture.13, 14, 20, 21 Ocular albinism itself may manifest as congenital nystagmus, photophobia, reduced visual acuity, color vision impairment, and progressive vision loss.9, 10, 13, 22, 23

Of note, the blood smear of patients with nCHS is diagnostic and will demonstrate peroxidase‐positive giant granules within leukocytes; it is cheaper and more feasible than genetic testing in many places and allows easy screening whenever nCHS is considered. Unfortunately, there is no curative treatment for nCHS to date, and management remains symptomatic.

In conclusion, clinicians should be considering nCHS in anyone with young‐onset parkinsonism and should look out for tell‐tale features such as albinism, bleeding diathesis, or frequent infections.

Even though the exact pathomechanisms remain elusive, impairment of lysosomal trafficking is what nCHS shares with some other genetic causes of parkinsonism, for example, mutations in ATP13A2, LRRK2, SNCA (α‐synuclein), or GBA (glucocerebrosidase).24

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

B.B.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3A, 3B

K.P.B.: 3B

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: B.B. and K.P.B. hold a research grant from the Gossweiler Foundation. B.B. received travel grants from the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) and the EFNS‐ENS. K.P.B. holds grants from the National Institute for Health Research RfPB, a Medical Research Council (MRC) Wellcome Strategic grant (ref. no.: WT089698), and Prakinson's Disease UK (ref. no.: G‐1009). K.P.B. has received honoraria/financial support to speak at/attend meetings from GlaxoSmithKline GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ipsen, Merz, Sun Pharma, Allergan, Teva Lundbeck, and Orion Pharmaceutical companies.

Full Financial Disclosures: K.P.B. has received honoraria/financial support to speak at/attend meetings from GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ipsen, Merz, Sun Pharma, Allergan, Teva Lundbeck and Orion pharmaceutical companies. K.P.B. holds grants from an MRC Wellcome Strategic grant (ref. no.: WT089698) and Parkinson's Disease UK (ref. no.: G‐1009). K.P.B. and B.B. hold a grant from the Gossweiler Foundation. B.B. has received travel grants from the MDS, EFNS, ENS, and AAN.

Supporting information

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video 1. The video shows the 32‐year‐old patient with akinetic‐rigid parkinsonism. Testing the pupillary reflexes reveals translucency of the iris, which is the only clear sign of his mild oculocutaneous albinism. Eye movement examination shows broken pursuit and slight slowing on both horizontal and vertical plane. There is bilateral bradykinesia. On finger tracking, cerebellar ataxia becomes apparent with mild dysmetria and overshoot. The plantar response is extensor on the right and equivocal on the left, whereas deep tendon reflexes are absent and foot deformities (pes cavus) are apparent.

Acknowledgments

B.B. thanks Prof. H.M. Meinck (Heidelberg) for his support and help in taking the videos.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Nagle DL, Karim MA, Woolf EA, et al. Identification and mutation analysis of the complete gene for Chediak‐Higashi syndrome. Nat Genet 1996;14:307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beguez‐Cesar AB. Neutropenia cronica maligna familiar con granulaciones atipicas de los leucocitos. Bol Soc Cubana Pediatr 1943;15:900–922. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steinbrinck W. Uber eine neue Granulationsanomalie der Leukocyten. Dtsch Arch Klin Med 1948;193:577–581. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chediak M. Nouvelle anomalie leukocytaire de caractere constitutionnel et familiel. Rev Hematol 1952;7:362–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Higashi O. Congenital gigantism of peroxidase granules. Tohoku J Exp Med 1954;59:315–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karim MA, Suzuki K, Fukai K, et al. Apparent genotype‐phenotype correlation in childhood, adolescent, and adult Chediak‐Higashi syndrome. Am J Med Genet 2002;108:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jacobi C, Koerner C, Fruehauf S, Rottenburger C, Storch‐Hagenlocher B, Grau AJ. Presynaptic dopaminergic pathology in Chediak‐Higashi syndrome with parkinsonian syndrome. Neurology 2005;64:1814–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhambhani V, Introne WJ, Lungu C, Cullinane A, Toro C. Chediak‐Higashi syndrome presenting as young‐onset levodopa‐responsive parkinsonism. Mov Disord 2013;28:127–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Uyama E, Hirano T, Ito K, et al. Adult Chédiak‐Higashi syndrome presenting as parkinsonism and dementia. Acta Neurol Scand 1994;89:175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sheramata W, Kott HS, Cyr DP. The Chediak‐Higashi‐Steinbrinck syndrome. Presentation of three cases with features resembling spinocerebellar degeneration. Arch Neurol 1971;25:289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Silveira‐Moriyama L, Moriyama TS, Gabbi TV, Ranvaud R, Barbosa ER. Chediak‐Higashi syndrome with parkinsonism. Mov Disord 2004;19:472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hauser RA, Friedlander J, Baker MJ, Thomas J, Zuckerman KS. Adult Chediak‐Higashi parkinsonian syndrome with dystonia. Mov Disord 2000;15:705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weisfeld‐Adams JD, Mehta L, Rucker JC, et al. Atypical Chédiak‐Higashi syndrome with attenuated phenotype: three adult siblings homozygous for a novel LYST deletion and with neurodegenerative disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tardieu M, Lacroix C, Neven B, Bordigoni P, de Saint Basile G, Blanche S, Fischer A. Progressive neurologic dysfunctions 20 years after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for Chediak‐Higashi syndrome. Blood 2005;106:40–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimazaki H, Honda J, Naoi T, et al. Autosomal‐recessive complicated spastic paraplegia with a novel lysosomal trafficking regulator gene mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:1024–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mathis S, Cintas P, de Saint‐Basile G, Magy L, Funalot B, Vallat JM. Motor neuronopathy in Chediak‐Higashi syndrome. J Neurol Sci 2014;344:203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pettit RE, Berdal KG. Chédiak‐Higashi syndrome. Neurologic appearance. Arch Neurol 1984;41:1001–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Misra VP, King RH, Harding AE, Muddle JR, Thomas PK. Peripheral neuropathy in the Chediak‐Higashi syndrome. Acta Neuropathol 1991;81:354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kritzler RA, Terner JY, Lindebaum J, Magidson J, Williams R, Presig R, Phillips GB. Chediak‐Higashi Syndrome. Cytologic and serum lipid observations in a case and family. Am J Med 1964;36:583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blume RS, Wolff SM. The Chediak‐Higashi syndrome: studies in four patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1972;51:247–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manoli I, Golas G, Westbroek W, et al. Chediak‐Higashi syndrome with early developmental delay resulting from paternal heterodisomy of chromosome 1. Am J Med Genet A 2010;152A:1474–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grønskov K, Ek J, Brondum‐Nielsen K. Oculocutaneous albinism. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;2:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sayanagi K, Fujikado T, Onodera T, Tano Y. Chediak‐Higashi syndrome with progressive visual loss. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2003;47:304–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tofaris GK. Lysosome‐dependent pathways as a unifying theme in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2012;27:1364–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wolf J, Jacobi C, Breer H, Grau A. Chediak‐Higashi syndrome. Nervenarzt 2006;77:148, 150–2, 155–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weary PE, Bender AS. Chediak‐Higashi syndrome with severe cutaneous involvement. Occurrence in two brothers 14 and 15 years of age. Arch Intern Med 1967;119:381–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video 1. The video shows the 32‐year‐old patient with akinetic‐rigid parkinsonism. Testing the pupillary reflexes reveals translucency of the iris, which is the only clear sign of his mild oculocutaneous albinism. Eye movement examination shows broken pursuit and slight slowing on both horizontal and vertical plane. There is bilateral bradykinesia. On finger tracking, cerebellar ataxia becomes apparent with mild dysmetria and overshoot. The plantar response is extensor on the right and equivocal on the left, whereas deep tendon reflexes are absent and foot deformities (pes cavus) are apparent.