Short abstract

RAND researchers review survey methods, sample demographics, key findings, and policy implications from the 2015 Health Related Behaviors Survey of active-duty service members.

Keywords: Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations, Health and Wellness Promotion, Health Risk Behaviors, Health-Related Quality of Life, HIV and AIDS, Mental Health and Illness, Military Force Deployment, Military Personnel, Obesity, Sexual Behavior, Sleep, Substance Use, United States Air Force, United States Army, United States Coast Guard, United States Marine Corps, United States Navy

Abstract

The Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS) is the U.S. Department of Defense's flagship survey for understanding the health, health-related behaviors, and well-being of service members. In 2014, the Defense Health Agency asked the RAND Corporation to review previous iterations of the HRBS, update survey content, administer a revised version of the survey, and analyze data from the resulting 2015 HRBS of active-duty personnel, including those in the U.S. Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard. This study details the methodology, sample demographics, and results from that survey in the following domains: health promotion and disease prevention; substance use; mental and emotional health; physical health and functional limitations; sexual behavior and health; sexual orientation, transgender identity, and health; and deployment experiences and health. The results presented here are intended to supplement data already collected by the Department of Defense and to inform policy initiatives to help improve the readiness, health, and well-being of the force.

The Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS) is the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD)'s flagship survey for understanding the health, health-related behaviors, and well-being of service members. The survey includes content areas—such as alcohol, tobacco, and substance use, as well as mental and physical health, sexual behavior, and postdeployment problems—that may affect force readiness or the ability to meet the demands of military life. The Defense Health Agency asked the RAND Corporation to review previous iterations of the HRBS, update survey content, administer a revised version of the survey, and analyze data from the resulting 2015 HRBS of active-duty personnel in the U.S. Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard.

Total Force Fitness (TFF) is a useful framework for conceptualizing how data from the HRBS can help DoD create and maintain a ready force. TFF is a holistic approach to well-being that focuses on both mind and body in the following eight domains: psychological, spiritual, social, physical, medical and dental, nutritional, environmental, and behavioral. Factors within each domain contribute to a service member's ability to meet the demands of military life. In other words, these factors set the stage for readiness. And by monitoring aggregate levels of key factors, the armed forces can assess how prepared they are to accomplish their missions.

The 2015 HRBS contains factors in all of the eight TFF domains. We highlight some of the key factors in the list below:

psychological: depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide and suicide ideation

spiritual: complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)1

social: marital status, social support

physical: physical activity, functional limitations

medical and dental: chronic conditions, medication use

nutritional: energy drink use, supplement use

environmental: deployment experiences

behavioral: alcohol use, tobacco use, substance use, sexual behavior, sleep.

This study reviews survey methods, sample demographics, key findings, and policy implications. Key health outcomes and health-related behaviors are organized around the following domains: health promotion and disease prevention; substance use; mental and emotional health; physical health and functional limitations; sexual behavior and health; sexual orientation, transgender identity, and health; and deployment experiences and health.

One key limitation of the 2015 HRBS is the low response rate (discussed later). Future versions of the survey will need to address the possible reasons for this, particularly how the sample is selected and the survey is implemented. Based on our experiences, we offer some recommendations in the final section of this summary.

Methodology

Starting from the 2011 and 2014 versions of the HRBS, the RAND team revised and edited the survey (e.g., removed some items; improved skip patterns; aligned scales with existing, validated measures used in civilian research; and added items relevant to current and emerging health issues related to readiness) with help from the sponsor, as well as a group of subject-matter experts across DoD and the U.S. Coast Guard. The final survey was approved by RAND's Institutional Review Board (known as the Human Subjects Protection Committee), ICF International's Institutional Review Board,2 the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness's Research Regulatory Oversight Office, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs and the Defense Health Agency's Human Research Protection Office, the Coast Guard's Institutional Review Board, and the DoD Security Office. All survey materials included the survey report control system license number: DD-HA(BE)2189 (expires February 9, 2019).

The sampling frame of the 2015 HRBS included all active component personnel who were not deployed as of August 31, 2015, and not enrolled as cadets in service academies, senior military colleges, and other Reserve Officers' Training Corps programs.3 Personnel in an active National Guard or reserve program and full-time National Guard members and reservists were classified as members of their reserve-component branch of service and excluded from our population of interest. We used data provided by the Defense Manpower Data Center to construct the sampling frame based on three strata: service branch, pay grade, and gender.

The 2015 HRBS disproportionately sampled from strata. We determined our sample size within each stratum using power calculations based on response rates from the 2011 HRBS. We used a different sampling strategy for the Coast Guard, sampling half of the service members within each stratum defined by pay grade and gender. All stratum-specific sample sizes were capped at 75 percent of the total stratum size. After determining the primary sample strata sizes, we sampled service members within each stratum with equal probability and without replacement.

A total of 1,374,590 service members were in the eligible population, and we invited 201,990 to participate in the survey via letter; we subsequently sent postcard or email reminders. All surveys were completed on the web and were completely anonymous.

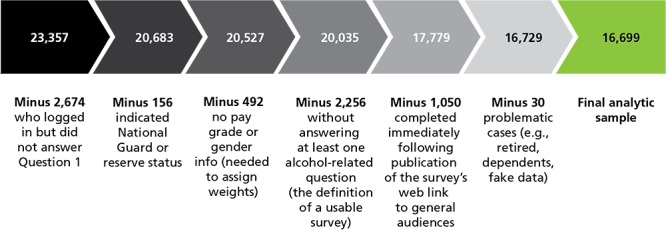

Of the service members invited to participate, 23,357 logged into the survey website. Figure 1 depicts how we got from that number to the final analytic sample of 16,699 surveys. Of the 23,357 individuals who logged in, a little fewer than 2,700 did not proceed through the front material to the first question, and we considered these nonusable surveys. We removed from our sample the 156 respondents who indicated that they were in a reserve or National Guard component and not on active duty. Roughly 500 respondents did not provide enough information to allow a poststratification weight to be computed (e.g., they had missing self-reported data on service branch, pay grade, or gender).4 We dropped an additional 2,256 surveys that did not meet our criterion for a usable survey (that is, a weight could not be computed or the respondent did not provide at least one response to an alcohol-related item; this is the same definition used in the 2011 HRBS). We also removed 1,050 surveys that were completed immediately following the publication of the survey's web link on af.mil, in the Air Force Times, and in Military Times, which could have contaminated our stratified random sampling frame.5 Finally, we removed 30 respondents who said they were currently retired or a dependent or who provided obviously false data (e.g., a pay grade and job title that did not reasonably match).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the 2015 HRBS Final Analytic Sample

The overall response rate was 8.6 percent.6 The response rate was highest among Coast Guard (20.4 percent), followed by Air Force (14.2 percent), Navy (6.7 percent), Marine Corps (6.6 percent), and Army (4.7 percent). Senior officers (O4–O10) had the highest response rate (20.6 percent), and junior enlisted (E1–E4) had the lowest (3.1 percent). The response rate was 7.8 percent for men and 10.2 percent for women.

We tested differences in health outcomes and health-related behaviors by domain across levels of key factors or by subgroups (service branch, pay grade, gender, age group, race/ethnicity, and education level) using a two-stage procedure. First, we used the Rao-Scott chi-square test as an overall test of the relationship between the outcome and the factor. This tests the hypothesis that there is any difference in the outcome across levels of the factor. We used a simple t-test to explore statistically significant relationships between the outcome and the factor, adjusting the p-values for multiple comparisons using the Tukey-Kramer method, which is designed to account for the multiple testing associated with all possible pairwise comparisons across factor levels. We computed confidence intervals for percentages using the Clopper-Pearson method (exact binomial confidence intervals) and confidence intervals for all other data types using a normal approximation.

Only statistically significantly different subgroup differences (p < 0.05) are described in the text.

Sample Demographics

Table 1 presents the distribution of service branch, pay grade, and gender from the 2015 HRBS weighted respondent sample and from a September 2014 sample of the DoD population of active-duty service members, which can be used as a point of comparison.7 The first column of data includes the Coast Guard portion of the HRBS sample. Because the 2014 DoD comparison population did not include the Coast Guard, the second column in the table uses only respondents from the four DoD services—the Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, and Navy. Finally, Table 1 does not include confidence intervals because the respondent sample was weighted to exactly match the sampling frame on service branch, pay grade, and gender.

Table 1.

Distribution of Service Branch, Pay Grade, and Gender in the 2015 HRBS Weighted Respondent Sample, with 2014 DoD Comparison

| 2015 HRBS Weighted Respondent Sample with Coast Guard (%) | 2015 HRBS Weighted Respondent Sample Without Coast Guard (%) | 2014 DoD Active-Duty Population (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service branch | |||

| Air Force | 22.3 | 23.0 | 23.6 |

| Army | 37.3 | 38.5 | 38.0 |

| Marine Corps | 14.0 | 14.4 | 14.2 |

| Navy | 23.4 | 24.1 | 24.2 |

| Coast Guard | 3.0 | Excluded* | NA** |

| Pay grade | |||

| E1–E4 | 44.2 | 44.5 | 43.2 |

| E5–E6 | 29.1 | 28.9 | 29.1 |

| E6–E9 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 10.0 |

| W1–W5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| O1–O3 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.9 |

| O4–O10 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.4 |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 84.4 | 84.4 | 84.9 |

| Women | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.1 |

SOURCE: The information in the first two columns is from the 2015 HRBS; the third column is from Defense Manpower Data Center, 2014.

NOTE: All HRBS data are weighted.

Coast Guard data were not included in this calculation.

NA = not applicable. DoD does not maintain demographic information about the Coast Guard.

Based on Table 1, the largest portion of the weighted respondent sample was in the Army (38.5 percent), and the largest pay grade group was junior enlisted ranks between E1 and E4 (44.5 percent). The overall distribution of respondents by pay grade mirrors the benchmark active-duty population.

Other demographic characteristics (for all five service branches) include the following:

Among the weighted respondent sample, 84.4 percent were men. More than two-thirds of the sample (70.6 percent) was under age 35.

Most of the weighted respondent sample was non-Hispanic white (58.4 percent), with Hispanics being the largest minority group (16.4 percent). The remaining sample was 11.5 percent non-Hispanic black, 5.1 percent non-Hispanic Asian, and 8.5 percent other (which included Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial respondents).

About one-fifth (20.4 percent) of the weighted respondent sample had a high school diploma, General Educational Development (GED) certification, or less; 48.5 percent had attended some college; and 31.0 percent had at least a bachelor's degree.

Overall, 57.3 percent of the weighted respondent sample was married; 35.2 percent was single; and 7.5 percent was separated, divorced, or widowed. In addition, 40.5 percent of the weighted respondent sample had at least one dependent under age 18 in the home.

Among the weighted respondent sample, 59.5 percent reported living off the installation or base, 23.7 percent lived in dorms or barracks on the installation or base, 15.5 percent lived on an installation or base in privatized housing, and 1.3 percent lived in some “other” housing situation (e.g., with parents or in temporary housing).

Although not included in Table 1, we also examined the pay grade and gender distributions among only the Coast Guard sample. The Coast Guard is evenly split between the E1–E4 and E5–E6 pay grades (34.2 percent in each), with an additional 10.9 percent senior enlisted (E6–E9), 4.2 percent warrant officers (W1–W5), 9.8 percent junior officers (O1–O3), and 6.6 percent mid-grade and senior officers (O4–O10). The gender distribution of the Coast Guard is similar to that of the DoD services: 84.8 percent men and 15.2 percent women.

The following section presents results by key health outcome and health-related behavior domains. Quantitative results generally refer to point estimates from the weighted sample. When interpreting comparisons between the U.S. active-duty military and the general U.S. population, it is important to keep in mind the demographic differences (e.g., gender, age) between the two. These, as well as differences in unobservable characteristics (e.g., personality traits), may make direct comparisons difficult to interpret.

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Within this domain, we examined physical activity, weight, routine medical care, CAM, sleep health, supplement use, and texting while driving. Key findings include the following:

Based on 2015 survey estimates, active-duty service members met or exceeded Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) targets for physical activity.8 Nevertheless, roughly one in four service members (24.4 percent) reported that they exercise as much as they would like, and work commitments were the most frequently cited reason for lack of exercise (38.8 percent). More than three-fourths of service members (80.5 percent) reported that they play electronic games outside of work or school for less than two hours per day; electronic game play is often a sedentary behavior that is not conducive to physical activity.

Survey estimates from the 2015 HRBS show that about one-third (32.5 percent) of active-duty service members aged 20 or older were a healthy (normal) weight, which is slightly below the HP2020 target (33.9 percent) and the percentage reporting normal weight in the 2011 HRBS (34.7 percent).9 In addition, 14.7 percent of service members were obese, which is well within the HP2020 goal of no more than 30.5 percent obese.

However, when looking at individual weight categories—underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese—the majority of active-duty service members (65.7 percent) were overweight or obese. It is important to note that body mass index, which was used to categorize individuals as overweight or obese, is an indirect measure of body fat, and muscular service members may have been misclassified into the overweight or obese categories.

Among active-duty service members, 93.2 percent reported having a routine doctor checkup within the past two years, a practice that may help identify the early onset of chronic disease and ensure appropriate preventive care. DoD regulations require service members to have an annual physical examination.

Nearly half (47.6 percent) of service members used CAM, such as massage therapy, relaxation techniques, exercise or movement therapy, and creative outlets (e.g., art, music, writing therapy). The best current estimates for the U.S. population suggest that 38 percent of the general population has used CAM (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2007), and the 2005 HRBS estimated that 45 percent of active-duty service members used CAM.10

More than half of active-duty service members got less sleep than they need (56.3 percent), and 29.9 percent were moderately or severely bothered by lack of energy due to poor sleep. In addition, 8.6 percent reported using sleep medications every day or almost every day.

Overall, 32.0 percent of service members reported using at least one dietary supplement daily. Daily supplement use ranged from 5.9 percent for herbal supplements to 16.9 percent for protein powder. Current estimates suggest that just more than half (53 percent) of U.S. adults use at least one dietary supplement (Gahche et al., 2011). Use of joint supplements, including fish oil, increases with age; however, use of protein powder and body building supplements decreases with age.

Among active-duty service members, 51.0 percent used caffeine-containing energy drinks (CCEDs) in the past month, 16.8 percent used them weekly, and 7.2 percent used them daily. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that 45 percent of deployed service members consumed CCEDs daily and 15 percent consumed three or more per day (CDC, 2012).

Overall, 12.8 percent of service members frequently (6.1 percent) or regularly (6.7 percent) texted or emailed while driving.

Substance Use

Within this domain, we examined use of alcohol; tobacco; illicit drugs; and prescription drugs, including use as prescribed, misuse (i.e., using a drug without a valid prescription), and overuse (i.e., using more of a drug than prescribed). Key findings include the following:

According to survey estimates, nearly one in three service members (30.0 percent) were current binge drinkers. In the 2011 HRBS, the rate of binge drinking was 33.1 percent, and according to the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the rate among U.S. adults (over age 18) was 24.7 percent (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ], 2015).

Rates of hazardous drinking, as measured by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) for Consumption (AUDIT-C), were also high (35.3 percent). The 2008 HRBS, using the AUDIT, found that 33.1 percent of active-duty service members met the criteria for hazardous drinking.11

One in 12 service members (8.2 percent) experienced serious consequences (e.g., “I hit my spouse/significant other after having too much to drink”) from drinking in the past year.

Among active-duty service members, 68.2 percent perceived the military culture as supportive of drinking, and 42.4 percent indicated that their supervisor does not discourage alcohol use. These perceptions were more common among younger and junior enlisted personnel, who were the most likely to binge drink. Service members were as likely to report purchasing alcohol mainly on base as they were to report purchasing it mostly off base.

According to our survey, 13.9 percent of service members currently smoked and 7.4 percent smoked daily. Nevertheless, cigarette smoking was less common among the military than the general population (where 16.8 percent were current cigarette smokers and 12.9 percent were daily smokers) (CDC, 2015), and it has decreased among service members by nearly half since 2011.

Among active-duty service members, 16.9 percent reported past-week exposure to secondhand smoke at work.

Smokeless tobacco use remains relatively high in the military compared with civilians: Among service members in our survey, 12.7 percent currently used smokeless tobacco, while 3.4 percent of the general U.S. population did in a 2015 study (CBHSQ, 2015).

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use is increasing, as 35.7 percent of service members reported ever having tried it (a nearly eight-fold increase since 2011), and 11.1 percent reported being daily e-cigarette smokers (a three-fold increase since 2011). In 2014, 12.6 percent of the general population had ever tried e-cigarettes and 3.7 percent were current users (used some days or every day) (Schoenborn and Gindi, 2015).

More than three-fourths of service members (80.7 percent) reported buying cigarettes on base. About one-fourth (25.6 percent) felt that tobacco use is strongly discouraged by their supervisor.

Rates of illicit drug use were substantially lower among service members than among the general U.S. population. For example, current and past-year marijuana users made up 8.5 percent and 13.3 percent, respectively, of U.S. adults in 2014. In the same year, 10.3 percent of U.S. adults were current and 16.6 percent were past-year users of any illicit drug (CBHSQ, 2015). In 2015, use of any illicit drug in the past year, including marijuana or synthetic cannabis, was reported by 0.7 percent of service members.

Among service members, 21.0 percent reported use of opioid pain relievers in the past year, more than twice the percentage who used sedatives, stimulants, or anabolic steroids in the same time frame. Opioids were also more likely to be misused (2.4 percent used them without a prescription) and overused (0.7 percent used more than prescribed). However, the percentage of service members currently using opioid pain relievers was 6.2 percent in 2015, compared with 10.4 percent in 2011.

Mental and Emotional Health

We examined mental health indicators (i.e., probable depression, anxiety, and PTSD); social and emotional factors associated with mental health (i.e., anger and aggression, high impulsivity); unwanted sexual contact and physical abuse history; self-harm, including suicide ideation and suicide attempts; and mental health service utilization and how it is affected by stigma. Key findings include the following:

Among active-duty service members, 17.9 percent experienced at least one of three mental health problems—probable depression (9.4 percent), probable generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (14.2 percent), or probable PTSD (8.5 percent)—and 9.7 percent suffered from two or more disorders. Although the prevalence of probable depression in service members was comparable to that in the general population (where it was 6 percent in the past year) (CBHSQ, 2015), the prevalence of probable GAD and probable PTSD in the past year may be higher than that in the general population (where it was 3 percent and 4 percent, respectively) (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005).

Among active-duty service members, 47.0 percent reported aggressive behavior in the past month, and 8.4 percent reported at least five episodes of such behavior; 12.7 percent met the criteria for high impulsivity.

Lifetime unwanted sexual contact was reported by 16.9 percent of service members and was reported far more often by women (46.1 percent) than men (11.7 percent). The 2011 HRBS estimated that 14.3 percent of service members reported any history of unwanted sexual contact in their lifetime. The majority of 2015 HRBS respondents (72.2 percent) reported that these events occurred while not on active duty, and 38.2 percent reported an event that occurred on active duty; 10.4 percent reported an unwanted sexual contact event both when on active duty and when not on active duty.

Lifetime physical abuse was reported by 13.0 percent of service members; this percentage was 17.1 percent in the 2011 HRBS. The data indicate that although relatively few military personnel have experienced physical abuse while on active duty (23.2 percent), a larger percentage of personnel experienced physical abuse while not on active duty (79.3 percent). In addition, 2.4 percent reported a physical abuse both when on active duty and when not on active duty.

Lifetime non-suicidal self-injury was reported by 11.3 percent of service members, and 5.1 percent reported that this behavior occurred since joining the military. These figures are comparable to the 2011 HRBS.

Almost one-fifth (18.1 percent) of service members reported thinking about trying to kill themselves at some point in their lives (12.3 percent since joining the military and 6.3 percent in the past 12 months), which is well above the roughly 4 percent reported from 2008 to 2014 in the general population (Lipari et al., 2015).

Overall, 5.1 percent of service members reported that they attempted to kill themselves at some point in their lives (2.6 percent since joining the military and 1.4 percent in the past 12 months). The past-year rate of suicide attempts is three times higher than reported in the 2011 HRBS (0.5 percent) and again higher than observed in the general population, where the rate has been roughly 0.5 percent of adults 18 and older from 2008 to 2014 (Lipari et al., 2015).

Among active-duty service members, 29.7 percent reported a self-perceived need for mental health services in the past 12 months, while 17.5 percent reported that others perceived that they should seek treatment. Self-assessed need for treatment in the 2011 HRBS was similar at 25.6 percent.

About one in four service members (26.2 percent) reported using mental health services in the past year. The HRBS percentage of service members reporting that they use mental health services has increased over time (2002: 12.2 percent;12 2005: 14.6 percent; 2008: 19.9 percent; 2011: 24.9 percent), possibly in part because of the addition of survey items assessing self-help support group visits (starting in 2005) and visits to some “other source of counseling, therapy or treatment” (2015).

Service members were more likely to report receiving mental health services from a specialist (e.g., psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker) (18.8 percent) than from a general medical doctor (9.9 percent) or from a civilian clergyperson or military chaplain (8.0 percent).

The average active-duty service member reported 4.5 mental health visits in the past year. Of these, 0.8 were to a civilian provider (e.g., paid out of pocket, by TRICARE, or by other private insurance), 2.5 were to a military provider, and 1.1 were to a self-help group or other provider.

Among service members who said they needed care in the past year but did not receive it (36.1 percent), the most frequently endorsed reasons for not receiving mental health treatment were a desire to handle one's own problem (61.5 percent), belief it would harm one's career (34.5 percent), belief that treatment would not help (33.5 percent), fear that the supervisor would have a negative opinion of the service member (31.5 percent), and concerns about confidentiality (30.1 percent).

Among active-duty service members, regardless of need for or actual receipt of care, 35.0 percent indicated that seeking mental health treatment is damaging to one's military career. Although a downward trend was observed in the early 2000s, since the 2008 HRBS, the decline in perceived stigma has essentially leveled off (2002: 48.1 percent; 2005: 44.1 percent; 2008: 36.1 percent; 2011: 37.7 percent).

Physical Health and Functional Limitations

We examined chronic conditions, physical symptoms, and health-related functional limitations. Key findings include the following:

About two in five service members (38.6 percent) reported at least one diagnosed chronic physical health condition in their lifetime, and 6.2 percent reported three or more conditions. The most common provider-diagnosed conditions were high blood pressure (17.7 percent), high cholesterol (13.3 percent), and arthritis (12.3 percent). The prevalence of most chronic conditions (i.e., high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, arthritis) was lower among active-duty service members than the general U.S. population; however, demographic differences (i.e., distribution of age, gender, employment status) between the military and general population make direct comparisons difficult.

The percentage of service members taking related medications for their diagnosed condition ranged from 3.9 percent among service members with skin cancer to 38.5 percent among those with physician-diagnosed ulcers.

Among active-duty service members, 35.7 percent reported that they were bothered a lot by at least one physical symptom (including headaches) in the past 30 days. One in five service members (21.1 percent) had high physical symptom severity (based on a survey of eight common physical symptoms). About one-third of service members reported that a health problem led to at least moderate impairment at work or school (33.0 percent), in their social life (30.0 percent), or in their family life/home responsibilities (30.5 percent).

Among active-duty service members, 3.0 percent reported missing more than 14 days of service in the past month because of physical or emotional health problems, while 13 percent reported reduced work productivity for more than 14 work days in the past month.

Sexual Behavior and Health

Within this domain, we examined high-risk sexual behavior in the past year, including sex with more than one partner, sex with a new partner without using a condom, experience of a sexually transmitted infection (STI), inconsistent use of birth control during most-recent vaginal sex, and unintended pregnancy. Key findings include the following:

Among active-duty service members, 19.4 percent reported more than one sexual partner in the past year.

More than one-third (36.7 percent) had sex with a new partner in the past year without using a condom.

STI was reported by 1.7 percent of service members, compared with 1.4 percent in 2011.

The HRBS defines high risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection as having sex with more than one partner in the past year, having a past-year STI other than HIV, or being a man who had sex with one or more men in the past year. In the 2015 HRBS, 20.9 percent of service members were at high risk for HIV infection.

Overall, 73.5 percent of service members reported having been tested for HIV in the past year. Among service members at high risk for HIV infection, 79.4 percent were tested in the past year.

Multiplying the 20.6 percent of untested high-risk individuals by the 20.9 percent of personnel at high risk for HIV infection means that 4.3 percent of service members overall were both at high risk for HIV infection and untested in the past year.

Across all services, 22.2 percent of personnel used a condom the most-recent time they had vaginal sex. This percentage was significantly higher among unmarried and noncohabitating service members (34.8 percent) than among married or cohabiting service members (14.2 percent).

Among service members not already expecting a child or trying to conceive, 19.4 percent did not use birth control the most-recent time they had vaginal sex in the past year. Significant differences were found by marital status: Among unmarried (including noncohabiting) service members, this percentage was 12.2 percent; among married and cohabiting service members, it was 24.0 percent.

Unintended pregnancy was experienced or caused by 2.4 percent of military personnel. The percentage of unintended pregnancies reported by military women is about the same as that for women of reproductive age in the general population—4.8 percent for military women compared with 4.5 percent for civilian women (Finer and Zolna, 2016).

Two short-acting methods of contraception—birth control pills and condoms—were by far the most commonly used methods.

Sexual Orientation, Transgender Identity, and Health

The 2015 HRBS provides the first direct estimate of the percentage of service personnel who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT), as well as of their health-related behavior and status. Key findings include the following:

Based on the 2015 HRBS, LGBT personnel made up 6.1 percent of service members. In the U.S. general population in 2011, the percentage of LGBT adults was 3.4 (Gates and Newport, 2012). This is the most-recent estimate available.13

-

In the 2015 HRBS, lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) personnel (excluding transgender) constituted 5.8 percent of service members. With respect to LGB sexual identity, a recent national study of high school students in grades 9 through 12 found that 2.0 percent identified as gay or lesbian, 6.0 percent identified as bisexual, and 3.2 percent were not sure of their sexual identity (Kann et al., 2016). These estimates are somewhat higher than the estimates for adults reported by Ward and colleagues (2014) using the National Health Interview Survey, who found that 1.6 percent of adults between ages 18 and 64 identified as gay or lesbian, 0.7 percent identified as bisexual, and 1.1 percent identified as “something else,” stated “I don't know the answer,” or refused to provide an answer. Given the age profile of the HRBS sample (and the military in general), it is not surprising that our estimates of sexual identity fall somewhere between these two reports but align more closely with the younger population. Key 2015 HRBS findings related to sexual orientation and transgender identity include the following:

Sexual attraction: 2.2 percent of men and 7.6 percent of women reported themselves as mostly or only attracted to members of the same sex.

Sexual activity: 3.3 percent of men and 9.4 percent of women had had sex with one or more members of the same sex in the past 12 months.

Sexual identity: 5.8 percent of active-duty service members identified as LGB (with 0.3 percent not responding to the sexual identity question). If all nonresponders identified as LGB, the LGB percentage would be 6.0 percent.

Transgender identity: 0.6 percent of service members described themselves as transgender. This is the same as the percentage of U.S. adults who describe themselves in this manner (Flores et al., 2016). Less than 1 percent of respondents (0.4 percent) declined to answer the transgender question. If all nonresponders were in fact transgender, the overall transgender percentage would be 1.1 percent.

More women (16.6 percent) identified as LGBT than men (4.2 percent).

Among the service branches, the Navy had the largest percentage of self-identified LGBT service members at 9.1 percent. LGBT identity was highest among junior enlisted and younger (below age 35) service members.

LGBT personnel received routine medical care in percentages similar to non-LGBT personnel, with 81.7 percent reporting a routine checkup in the past 12 months.

LGBT personnel were less likely to be overweight than other service personnel.

-

LGBT personnel were more likely than non-LGBT personnel to have engaged in some risk behaviors, including the following:

binge drinking: 37.6 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 29.3 percent of non-LGBT personnel

current cigarette smoking: 24.8 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 16.0 percent of non-LGBT personnel

unprotected sex with a new partner: 42.4 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 35.6 percent of non-LGBT personnel

more than one sexual partner in the past year: 40.2 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 17.7 percent of non-LGBT personnel

STI in the past year: 7.4 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 1.4 percent of non-LGBT personnel

no birth control during the most-recent vaginal sex: 31.5 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 21.6 percent of non-LGBT personnel.

-

LGBT personnel were more likely to report experiencing mental health issues or a history of abuse, including the following:

moderate depression: 13.2 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 8.5 percent of non-LGBT personnel

severe depression: 13.7 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 8.8 percent of non-LGBT personnel

lifetime history of self-injury: 26.5 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 10.3 percent of non-LGBT personnel

lifetime suicide ideation: 32.7 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 17.1 percent of non-LGBT personnel

lifetime suicide attempt: 13.0 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 4.6 percent of non-LGBT personnel

suicide attempt in the past 12 months: 4.8 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 1.2 percent of non-LGBT personnel

lifetime history of unwanted sexual contact: 39.9 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 15.4 percent of non-LGBT personnel

ever physically abused: 21.4 percent of LGBT personnel compared with 12.4 percent of non-LGBT personnel.

Deployment Experiences and Health

Within this domain, we examined deployment frequency and duration, combat exposure, deployment-related injuries or traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), deployment-related substance use, and deployment-related mental and physical health. Key findings include the following:

-

Among active-duty service members, 61.3 percent reported at least one deployment since joining the military. Among those who deployed,

Four-fifths (80.9 percent) had experienced at least one combat deployment, and 60.1 percent had spent more than 12 months deployed in their military career.

More than one-third (38.4 percent) reported deployment starting in the past three years, and 64.3 percent of those deployments were to combat zones.

Among service members reporting at least one previous deployment, 64.9 percent reported exposure to at least one combat-related event, and 45.8 percent reported at least five such exposures. The most commonly reported lifetime combat exposures included taking fire from small arms, artillery, rockets, or mortars (49.8 percent); being sent outside the wire on patrols (42.1 percent); seeing dead bodies or remains (38.6 percent); firing on the enemy (35.7 percent); and suffering unit casualties (35.6 percent).

Of those reporting at least one previous deployment, 27.7 percent suffered a combat injury, 11.9 percent screened positive for deployment-related mild TBI (mTBI), and 8.6 percent reported postconcussive symptoms that could be related to a deployment-related injury, a concussion, or a head injury.

Two-thirds of service members who had ever deployed (67.6 percent) reported some substance use during their most-recent deployment, and use of alcohol (36.2 percent), cigarettes (28.0 percent), cigars (23.3 percent), smokeless tobacco (18.9 percent), and prescription drugs (18.9 percent) were far more common than marijuana (0.1 percent) or opiates (0.1 percent).

-

Among service members who were recently deployed (that is, deployed in the past three years), those with high levels of combat exposure were more likely than those with low to moderate exposure to report the following:

deployed use of smokeless tobacco (22.4 percent compared with 16.9 percent) and cigars (28.1 percent compared with 19.5 percent)

use of prescription drugs in the past year (36.2 percent compared with 23.7 percent)—specifically, stimulants (4.4 percent compared with 2.0 percent), sedatives (16.4 percent compared with 7.3 percent), pain relievers (25.8 percent compared with 17.1 percent), and antidepressants (14.0 percent compared with 4.9 percent)

alcohol use (48.6 percent compared with 28.9 percent) during their most-recent deployment

current binge drinking (34.6 percent compared with 28.2 percent).

-

Among service members deployed in the past three years, those with deployment-related probable mTBI (compared with those with no TBI) were

more likely to report using cigarettes (34.4 percent compared with 26.8 percent) and smokeless tobacco (26.8 percent compared with 18.2 percent) during their most-recent deployment

less likely to report using alcohol (29.2 percent compared with 41.6 percent) during their most-recent deployment

more likely to have used prescription medication during their most-recent deployment (32.1 percent compared with 17.6 percent) and more likely to report current use of prescription sedatives (23.9 percent compared with 9.5 percent), pain relievers (32.3 percent compared with 19.2 percent), and antidepressants (18.4 percent compared with 7.5 percent).

Among active-duty service members deployed in the past three years, 10.4 percent met the criteria for probable depression, 15.0 percent met the criteria for probable GAD, and 9.9 percent met the criteria for probable PTSD. Half of those deploying in the past three years (50.6 percent) reported aggressive behavior in the past month, and 8.4 percent reported such behavior at least five times in the past month. In addition, 12.2 percent met the criteria for high impulsivity.

-

Among active-duty service members deployed in the past three years, those with high exposure to combat were more likely than those with low or moderate exposure to report probable GAD (18.8 percent compared with 12.3 percent) and probable PTSD (12.8 percent compared with 7.9 percent). In addition,

Recently deployed service members with probable mTBI were nearly three times more likely to screen positive for probable depression (24.5 percent) than those without TBI (8.8 percent). Similarly, those with probable mTBI were about three times more likely than those without TBI to screen positive for probable GAD (35.3 percent compared with 12.6 percent) and probable PTSD (29.5 percent compared with 7.6 percent).

Recently deployed service members with probable mTBI were also more likely than those deploying but without TBI to report displaying any angry behavior in the past month (71.7 percent compared with 48.2 percent) or doing so at least five times in the past month (20.1 percent compared with 7.1 percent).

Among those deployed in the past three years, 11.7 percent reported lifetime non-suicidal self-injury.

-

With respect to suicide:

Among those deployed in the past three years, 17.7 percent reported lifetime suicide ideation, including 5.7 percent reporting having such thoughts in the past 12 months, 12.0 percent since joining the military, and 5.0 percent during a deployment.

Just under 5 percent (4.6 percent) of those deploying in the past three years reported a lifetime suicide attempt, with 1.3 percent reporting an attempt in the past 12 months, 2.4 percent reporting an attempt since joining the military, 2.6 percent reporting an attempt before joining the military, and 0.6 percent reporting an attempt during a deployment.

Among recently deployed members, those with high exposure to combat were more likely than those with low or moderate exposure to report suicide ideation since joining the military (15.7 percent compared with 9.8 percent) and during a deployment (6.8 percent compared with 3.7 percent).

Suicidal thoughts at any time in the past 12 months, since joining the military, or during a deployment were reported more than twice as often among those with probable mTBI (11.6 percent in the past 12 months, 24.8 percent since joining the military, and 10.6 percent during a deployment) than among those with no TBI (4.9 percent in the past 12 months, 10.5 percent since joining the military, and 4.3 percent during a deployment).

-

Among those deployed in the past three years, 22.8 percent had a high somatic symptom score, and 37.8 percent reported chronic symptoms. In addition,

Among recently deploying members, those with high levels of combat exposure were more likely than those with lower levels of combat exposure to have a high somatic symptom score (28.6 percent compared with 18.8 percent) and chronic symptoms (47 percent compared with 32 percent).

Among recently deployed service members, those with probable mTBI were more likely than those without TBI to have a high somatic symptom score (47.3 percent compared with 19.6 percent) and to report chronic symptoms (62.2 percent compared with 35.0 percent).

Key Subgroup Differences

We tested differences in each outcome by such characteristics as service branch, pay grade, gender, age group, race/ethnicity, and education level. Below, we highlight key findings by subgroup.

Service Branch

Differences across the services are likely tied to the very different demographics of service members in the Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard. Differences are also likely tied to the types of duties and missions conducted within each branch. With this in mind, we note the following findings:

The Army, at 29.8 percent, had the highest percentage of service members with at least 300 minutes of moderate physical activity per week (an HP2020 benchmark), while the Air Force had the lowest, at 20.0 percent.

Both the Air Force (35.3 percent) and the Marine Corps (37.8 percent) exceeded the HP2020 target for healthy weight. The prevalence of obesity ranged from 6.4 percent in the Marine Corps to 18.0 percent in the Army.

Service members in the Army (59.4 percent), Marine Corps (56.9 percent), and Navy (57.5 percent) were most likely to report receiving less sleep than what they need to feel refreshed and perform well. Respondents in the Army (33.2 percent), Marine Corps (32.8 percent), and Navy (32.8 percent) were also most likely to report a lack of energy due to poor sleep.

Daily body-building supplement use ranged from 7.6 percent in the Coast Guard to 17.7 percent in the Marine Corps.

Daily CCED consumption ranged from 3.9 percent in the Coast Guard to 11.8 percent in the Marine Corps.

Binge, heavy, and hazardous drinking varied substantially by service. These rates were lowest in the Air Force and highest in the Marine Corps, where nearly half of Marines engaged in hazardous drinking.

Marines were also most likely to perceive military culture as supportive of drinking and least likely to report that their supervisor strongly discourages alcohol use.

All forms of tobacco use (cigarettes, cigars, smokeless, and e-cigarettes) were more common in the Marine Corps.

The Army had the highest levels of prescription sedative, pain reliever, and antidepressant use, while the Coast Guard had the lowest. Prescription drug misuse was also highest in the Army and lowest in the Coast Guard.

The Army and Marine Corps had the highest levels of probable depression, GAD, and PTSD.

Prevalence of lifetime non-suicidal self-injury and lifetime suicide attempts was higher in the Army, Marine Corps, and Navy than in the Air Force or Coast Guard.

Army respondents (32.1 percent) had the highest use of mental health services, while Coast Guard respondents (17.5 percent) had the lowest.

Prevalence of at least one diagnosed chronic health condition (e.g., high blood pressure, diabetes, asthma) ranged from 31.6 percent in the Air Force to 46.0 percent in the Army.

The prevalence of physical symptoms in the past 30 days was highest in the Army (42.5 percent) and Marine Corps (40.4 percent) and lowest in the Coast Guard (24.3 percent). The Army (25.6 percent) and Marine Corps (25.8 percent) had the highest prevalence of high physical symptom severity on a somatic symptom scale.

The Marine Corps, followed by the Navy, had the highest percentage of members who were at high risk for HIV infection, who reported multiple sex partners in the past year, and who reported causing or experiencing an unintended pregnancy. The Marine Corps, Army, and Navy also had higher percentages than the Air Force and Coast Guard of members reporting sex with a new partner in the past year without using a condom.

Pay Grade

Many of the differences that we observed by pay grade stem from inherent differences in the military experiences, both positive and negative, that senior staff have had compared with their junior colleagues. Differences by pay grade are also likely highly correlated with differences across age and education level. Noteworthy differences we found include the following:

Relative to officers, enlisted service members were more likely to report having less than four hours of sleep during the work week, more likely to report being moderately or severely bothered by lack of energy due to poor sleep, and less likely to report being satisfied with their sleep.

The percentage of respondents reporting receiving routine medical care in the past two years was lowest among junior enlisted (92.6 percent) and highest among mid-grade and senior officers (95.9 percent).

Junior and mid-level enlisted members (E1–E6) tended to be more problematic drinkers than others. Junior enlisted service members (E1–E4) were also most likely to experience serious drinking consequences and productivity loss and to see military culture as supportive of drinking. Nevertheless, the group with the highest percentage of hazardous, possibly disordered, drinkers was junior officers (O1–O3 officers; 39.2 percent), which also had the second-highest percentage of binge drinkers.

One-fifth of junior enlisted service members currently used e-cigarettes, compared with 10.8 percent of mid-level enlisted personnel (E5–E6), 6.1 percent of senior enlisted personnel, 3.4 percent of warrant officers (W1–W5), 2.2 percent of junior officers, and 0.9 percent of mid-grade or senior officers (O4–O10).

Senior enlisted and warrant officers were more likely to use prescription sedatives, pain relievers, and antidepressants than others. Senior enlisted personnel were also most likely to misuse prescription drugs.

Officers reported lower levels of probable depression, GAD, and PTSD than their enlisted and warrant officer peers. Lifetime and past-12-month suicide ideation were lower among mid-grade and senior officers relative to all other pay grades.

Significantly more warrant and junior officers than senior non-commissioned officers (E7–E9) and senior officers endorsed the belief that seeking mental health treatment would damage their military career.

Enlisted service members were more likely to report being bothered “a lot” by at least one physical symptom, with 50.8 percent of senior non-commissioned officers doing so.

Junior enlisted service members were at higher risk than other members in nearly every sexual health category.

Gender

Data collection for the 2015 HRBS coincided with Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter's December 2015 announcement that, as of 2016, all combat jobs would be open to women, essentially ending all gender segregation in the military. Although it is not clear whether this policy change will eliminate gender differences across health and well-being outcomes, it may reduce disparities in exposure (e.g., combat-related trauma). Nonetheless, we did observe some differences across gender in our survey data. It will be important to track these trends going forward as women have the opportunity to expand their roles in the military. We note the following findings:

Men were more likely than women to report playing electronic games outside of work or school (e.g., iPads, laptops, handheld games) for at least two hours daily.

Women (64.2 percent) were more likely than men (44.5 percent) to report CAM use.

Men were more likely to report using supplements for joint health (11.2 percent compared with 9.0 percent for women), fish oil (15.9 percent compared with 13.9 percent), protein powder (17.9 percent compared with 11.2 percent), and supplements for body building (13.0 percent compared with 5.4 percent). Men were less likely to report using herbal supplements (5.5 percent compared with 8.2 percent for women) and weight-loss supplements (6.3 percent compared with 8.6 percent). Women were more likely to report never using CCEDs (66.4 percent compared with 45.8 percent for men).

Men were more likely than women to report binge (31.2 percent compared with 23.0 percent), heavy (6.1 percent compared with 1.3 percent), and hazardous (36.0 percent compared with 31.3 percent) drinking.

Women were more likely than men to report using prescription sedatives (16.8 percent compared with 9.7 percent), pain relievers (27.4 percent compared with 19.8 percent), and antidepressants (15.5 percent compared with 7.6 percent).

Women reported higher levels than men of lifetime unwanted sexual contact (46.1 percent compared with 11.7 percent) and lifetime physical abuse (18.9 percent compared with 11.9 percent).

Women were more likely than men to report being bothered a lot by headaches (19.1 percent compared with 10.5 percent); feeling tired or having low energy (31.7 percent compared with 21.7 percent); and experiencing at least one physical symptom (including headaches) (41.4 percent compared with 34.7 percent).

Age Group

Observed differences across age groups stem at least in part from cumulative exposure. Some differences across age groups are also due to younger individuals, whether in the military or not, engaging in riskier behaviors. Differences we found by age group among military members include the following:

-

Relative to those 45 or older, service members aged 17–24 were more likely to

use CCEDs weekly (21.5 percent compared with 4.8 percent) or daily (7.8 percent compared with 3.4 percent)

text while driving (8.2 percent compared with 2.6 percent)

be binge, heavy, and hazardous drinkers (37.3 percent, 9.5 percent, and 42.5 percent, respectively, compared with 14.8 percent, 2.1 percent, and 22.0 percent).

Service members aged 17–24 were also more likely to see military culture as supportive of drinking and less likely to see their supervisor as strongly discouraging drinking.

Service members aged 17–24 were more likely to meet the threshold for high impulsivity (22.0 percent compared with 10.9 percent for those aged 25–34, 6.6 percent for those aged 35–44, and 6.9 percent for those 45 or older).

Past-year suicide ideation was higher among those aged 17–24 relative to those 35 or older. Lifetime suicide attempts were also higher among younger service members. Younger service members were less likely to receive mental health care than their older peers.

The prevalence of any medical diagnosis for a chronic condition was 18.5 percent among service members aged 17–24 but 75.2 percent among those 45 or older.

Younger age was also consistently related to higher rates of sexual risk behaviors and negative outcomes, with the exception of use of condoms and other contraceptives during the most-recent vaginal sex in the past year; younger service members reported higher rates than older members on those measures.

Race/Ethnicity

Although it is not clear whether one should expect significant differences in health and health-related behaviors across racial or ethnic groups in the armed forces, such differences do exist in the civilian population. Where differences do exist, DoD can leverage this information to improve readiness among specific racial or ethnic groups and target intervention and policy to reduce such disparities. Noteworthy differences we found by race/ethnicity include the following:

Non-Hispanic whites were more likely to be hazardous or disordered drinkers (40.6 percent compared with 19.5 percent among non-Hispanic Asian and 18.8 percent among non-Hispanic black service members).

Non-Hispanic blacks were least likely to smoke cigarettes.

Non-Hispanic blacks and service members of the “other” race/ethnicity group (which includes Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, as well as multi-racial) had higher levels of probable PTSD.

Non-Hispanic whites and those in the “other” race/ethnicity category had higher lifetime suicide ideation rates than non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics.

Non-Hispanic blacks were least likely to report that seeking mental health treatment would damage their military career, while non-Hispanic whites and those of other races/ethnicities were most likely to endorse this belief.

Hispanics were most likely to report having more than one sex partner and having sex with a new partner without a condom; this group also had the largest percentage at high risk for HIV infection. Sex without contraception was less common among non-Hispanic whites and all other races/ethnicities than among non-Hispanic Asian service members.

Education Level

Differences across education level largely correlate with differences observed by pay grade, as officers tend to be more highly educated than their enlisted peers. Noteworthy differences by education level include the following:

Self-reported CAM use increased with education level, ranging from 38.4 percent among service members with no more than a high school education to 53.8 percent among those with a college degree.

Binge and heavy drinking were more common among those with no more than a high school diploma (38.1 percent and 9.9 percent, respectively) than among those with at least some college (28.9 percent and 5.2 percent, respectively) or at least a bachelor's degree (26.2 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively). Productivity loss due to drinking and serious consequences from drinking were more frequently reported by those with no more than a high school diploma (8.4 percent and 12.9 percent, respectively) than by those with a college degree (4.8 percent and 5.7 percent, respectively). Less-educated respondents were also more likely to report more use of tobacco in all forms studied.

College-degree holders were the least likely to have probable depression, GAD, or PTSD.

Less-educated members were more likely than their more-educated peers to have had multiple sex partners, had sex with a new partner without a condom, been at high risk for HIV infection, or had or caused an unintended pregnancy.

Limitations

Our findings are subject to many limitations common to survey research. First, response rates were lower in 2015 than in prior HRBSs and many other recent military surveys. Potential reasons for the low response rate in the 2015 HRBS include survey fatigue (the 2014 HRBS was still in the field well into 2015), survey length (the survey took roughly 45 minutes to complete), survey content (i.e., sensitive behaviors), and information technology issues (e.g., most calls to the help desk were about problems accessing the survey website). Low response rates do not automatically mean that the results are biased (Groves, 2006), but they do increase the likelihood that service members who did not respond were in some way qualitatively different from those who did respond. However, we have no way to assess how the bias might have affected the results. On the one hand, one could hypothesize that service members with the worst health or the most health problems did not participate when asked. If so, the results may overestimate the health of the force. On the other hand, if some service members were unhappy about the way DoD and the Coast Guard handled some specific aspect of health or health care (e.g., quality of mental health treatment) and wanted a mechanism to provide feedback, the results could possibly underestimate the health of the force. Low response rates also imply higher variances around point estimates; however, this added variance is captured in wider confidence intervals.

Second, because we made edits to prior HRBS content, largely to shorten the survey, responses may not be strictly comparable to those of prior versions. This is not true of every survey item, as many are directly comparable to prior surveys (e.g., tobacco and alcohol use, self-harm and suicide, mental health service utilization, stigma).

Third, comparison to civilian populations may also be problematic because, in addition to demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, race/ethnicity, education level) for which we might control in statistical analysis, there may be other, unknown differences between civilian and military populations that may influence outcomes for health, health-related behavior, and well-being.

Fourth, as with any self-reported survey, responses may reflect social desirability. That is, respondents may feel pressure to answer survey questions that make them appear healthier or confirm that they conform to social norms. This could be especially problematic in a survey like the HRBS, which asks about many sensitive behaviors.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

We offer two sets of policy implications. The first addresses ways in which DoD and the Coast Guard can improve the readiness, health, and well-being of the force. The second offers suggestions for future iterations of the HRBS.

Force Readiness, Health, and Well-Being

At the time this study was conducted, DoD had already experienced downsizing (since roughly 2012), and it was expected to face more cuts in manpower and other resources. Thus, it is more important than ever to understand how to strategically maximize force health and readiness. The results from the 2015 HRBS can help identify areas and subgroups where readiness may be at risk now or in the future. Therefore, we offer several observations to help DoD and the Coast Guard identify immediate and future threats to the readiness, health, and well-being of the force, and we outline relevant policy implications derived from those observations. We discuss these threats in order of magnitude, as determined by the research team.

Although DoD and the Coast Guard are doing well in several areas, a few health outcomes and health-related behaviors warrant immediate policy attention given their clinical importance. These outcomes and behaviors include the following:

Binge and hazardous drinking: Roughly one-third of service personnel met criteria indicative of hazardous drinking and possible alcohol use disorder. Nearly one-third of service members reported binge drinking in the past month. Problematic drinking could be addressed by shifting the culture and climate surrounding alcohol use (e.g., communicating disapproval of heavy drinking and changing on-base alcohol prices and sales policies).

Smoking and e-cigarette use: Cigarette smoking is a major health hazard. The health consequences of e-cigarette use are not yet established, but the dramatic increase in e-cigarette use, especially among younger service members, is worth attention now and continued tracking in the future.

Overweight or obesity: The large percentage of the population that continues to meet the criteria for being overweight or obese is cause for concern. Overweight or obese personnel reduce overall force fitness and readiness and pose policy issues for military recruitment, retention, and the standards used to qualify or disqualify individuals from service. In addition to directly affecting readiness, overweight or obese status is associated with morbidities (i.e., diabetes, asthma, hypertension, joint pain) that adversely affect readiness and health care utilization and costs. If the large percentage of overweight service members is indeed correlated with physical fitness (i.e., body mass index may be higher among those with more muscle mass), then this may be less of a concern. Unfortunately, the 2015 HRBS data do not allow us to determine if this is the case.

Inconsistent use of contraception: Inconsistent use of contraception increases the risk for unintended pregnancy and presents a possible threat to readiness (because pregnancies reduce personnel availability). Continued monitoring of use, as well as efforts to increase use of long-acting methods of contraception (e.g., oral contraceptives, intrauterine devices), are warranted.

High risk for HIV infection: High risk for HIV infection was defined as having sex with more than one partner in the past year, having a past-year STI other than HIV, or being a man who had sex with one or more men in the past year. Current attention should focus on unmarried (noncohabiting) service members, of whom more than 40 percent were in the high-risk category. Revisions to policy could mandate increased HIV testing frequency for all those at high risk for HIV infection and could implement interventions to increase use of condoms with new partners. High-risk behaviors should also be monitored into the future.

Sleep: More than half of service members reported getting less sleep than they need, and one-third were bothered by lack of energy due to poor sleep. Insufficient sleep is associated with adverse health outcomes and has the potential to impair military readiness.

Energy drinks: More than half of service members reported using energy drinks in the past month. CCEDs are associated with emergency room visits and other adverse health-related behaviors.

High absenteeism and presenteeism due to health conditions: Absenteeism refers to lost work days because of a health condition, and presenteeism refers to days present on duty but the usual level of performance is compromised because of a health condition. Overall, 13 percent of service members reported reduced productivity because of health conditions for at least two weeks in the past month. This has significant implications for productivity and suggests that there is a need to address this issue immediately through policy or programs that target the underlying health conditions (e.g., chronic disease, physical symptoms, functional impairment) that lead to reduced or limited productivity.

DoD and the Coast Guard should consider heightened scrutiny and continued monitoring of several health outcomes and health-related behaviors, especially those related to mental health treatment and suicide. Our findings include the following:

In the 2015 HRBS, more than one-third of respondents who stated they had a need for mental health counseling reported not receiving counseling from any source. Efforts should be made to characterize the population reach of existing mental health services and to identify when certain types of individuals (e.g., based on demographic or military factors) are not receiving needed care. Programs with the greatest reach should be identified, evaluated, and monitored for quality and effectiveness. Existing mechanisms, such as the Periodic Health Assessment, may be one way to identify service members in need of treatment.

Stigma associated with mental health treatment remains a concern. HRBS indicators suggest that modest decreases in perceived stigma occurred from 2002 to 2008. Since then, however, stigma levels have remained largely unchanged, even as DoD has experienced persistent pressure to better define, operationalize, track, and reduce it. Efforts are needed to develop, test, and implement consistent, military-relevant surveillance indices of mental health stigma, and research is needed to understand how and why stigma remains a barrier to care for many service members, despite DoD mitigation efforts.

Further, the findings presented here suggest that roughly half of mental health services were delivered by nonspecialists. Efforts should be made to better identify, improve, and evaluate the sources, quality, and outcomes of those nonspecialty mental health services in the military.

We also found that a significant minority of service members received mental health care in a civilian setting; future research should better determine the reasons that service members seek treatment options outside the military health system and the impact of these services on continuity of mental health care. Insufficient access to high-quality services and lack of continuity of care across the military and civilian systems may pose a real risk to service member well-being and to force health and readiness.

Findings from the 2015 HRBS indicate that suicide ideation, which may be a marker of distress and mental anguish, is a major concern among service members. The military is already devoting large amounts of funding to understand suicide in the military, but more information is needed on early precursors to suicide and how different strategies may be needed for different populations, depending on their levels of risk. Such prevention strategies also need to be evaluated to better understand their effectiveness, accessibility, and acceptability. The military continues to rely heavily on peer models (e.g., gatekeeper trainings) to prevent suicide, in which peers are instructed on how to intervene with service members in crisis. Little is known about whether service members have been witness to or concerned about such situations in the past; whether they have intervened; and if they did intervene, what they did, and if they did not intervene, why not. Understanding these nuances would allow the military to better tailor its prevention efforts and target its resources more effectively and efficiently.

Results from the 2015 HRBS suggest that, based on demographics (e.g., age group), certain groups of service members warrant targeted interventions to prevent multiple negative health outcomes and to improve current health-related behaviors. Cultural tailoring of prevention messages is a recommended public health strategy. For example, messages that resonate with service members who are 20 years old and single may not be as salient with those who are 40 years old and married. Similarly, messages that appeal to the Army or Marine Corps ethos may not work as well in the context of Air Force culture.

It is also worth noting that although targeted interventions may be designed with a specific subgroup of the population in mind, those interventions could benefit all active-duty service members. For example, health disparities between LGBT and non-LGBT service members warrant closer DoD and Coast Guard attention. Although one option is to target the LGBT population with clinical and population efforts, such an approach may stigmatize the target population. Therefore, it may be best to apply these efforts equally across the military, which could lead to broader population benefits. With regard to subgroups that might benefit from targeted interventions, our findings include the following:

Consistently, the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps reported higher levels of mental health problems, suggesting a particular focus on these branches. Service members in the Army and Marine Corps also reported the highest use of CCEDs and the lowest levels of sleep quality. Rates of binge and hazardous drinking were concerning across all service branches, particularly in the Marine Corps. Understanding the reasons for inter-service variation may lead to service-specific programs that more directly address service-specific needs.

Women and service members with lower education levels reported higher levels of mental health problems, including suicide ideation and attempts. Women also reported higher levels of impairment and presenteeism and lower levels of sleep quality. Binge drinking, loss of productivity related to drinking, sexual risk behaviors (e.g., multiple sex partners, sex with a new partner without a condom), and all forms of tobacco use were also greater among less-educated service members. Thus, these are high-risk groups, and efforts may need to be targeted directly to them.

Younger service members, particularly those aged 17–24, were more likely than older service members to use energy drinks regularly and engage in binge, heavy, and hazardous drinking and sexual risk behaviors (except condom use during the most-recent vaginal sex). In addition, a higher percentage of younger service members reported recent suicide ideation than older service members. Furthermore, high impulsivity was also more common among this group than among older service members, which suggests that there is an opportunity for military leaders to target prevention efforts by age group.

LGBT service members reported higher rates of mental health problems (e.g., depression, suicide ideation) and possible precursors to subsequent problems (e.g., history of unwanted sexual contact, history of physical abuse) than their non-LGBT peers. They also reported higher rates of some health-related risk behaviors, including smoking, binge drinking, STI, sex with more than one partner in the past year, and vaginal sex without use of birth control. These differences are not unlike those observed for LGBT people in the civilian population (Institute of Medicine, 2011). These findings suggest that policy and programmatic efforts are needed to target this population and that trends in the health and well-being of this population should continue to be monitored. This will be especially important in the Navy, which has the highest percentage of gay or bisexual men and of LGBT service members overall, and in the Marine Corps, which has the highest percentage of lesbian or bisexual women serving.

Finally, DoD and the Coast Guard should establish population benchmarks of health and health-related behaviors for the military. Some benchmarks currently exist, primarily in the form of requirements to do (or, in some cases, not to do) certain behaviors (e.g., receive an annual health exam, abstain from using illicit drugs). However, in other cases, like overweight and obese status or leader attitudes toward smoking or alcohol use, no clear benchmarks for the military exist. General population benchmarks are available for many health outcomes and health-related behaviors (e.g., HP2020), but it is not clear whether they are truly applicable to the military—a characteristically unique population. Although the ultimate goal for many behaviors may be zero incidence of them, such a goal may not be realistic or attainable, especially in the short term. Thus, it could be very useful for DoD and the Coast Guard to develop population benchmarks designed to move the population averages in the desired direction. Periodic review and updating of these benchmarks would also be needed.

Future Iterations of the HRBS

In this section, we offer suggestions for future iterations of the HRBS, based on several issues that we encountered during implementation of the survey. To provide some background for these recommendations, we offer a brief description of the environment in which we launched the survey. First, shortly before we sent invitation emails, we were alerted to a change in DoD information technology policy that meant that any hyperlinks included in emails sent from a non-DoD account would be identified as possibly hazardous and thus blocked. Further, some email servers were blocking invitation emails despite our attempts to “whitelist” the email address from which the invitations were sent and use the appropriate email certificates. Second, the 2014 HRBS had left the field only a few months prior to the 2015 survey beginning. The near overlap of the 2014 and 2015 HRBSs increased the survey burden on an already highly surveyed population. Third, while the survey assured anonymity, it asked about very sensitive topics, including some that could result in a service member being dismissed from the military, which likely made some respondents reluctant to answer. Together, these events and conditions set the stage for an implementation of the HRBS that was less than optimal. To improve implementation, we offer the following recommendations.

Dramatically shorten the survey and focus content. Originally designed to assess substance use, the HRBS has expanded well beyond that. Some of the data it requests (e.g., on service utilization) can be obtained from existing administrative data sets. By focusing more strictly on content that cannot be obtained elsewhere, the survey could be dramatically shortened. The current length of the survey makes it somewhat inflexible and unable to address new and emerging areas of concern. With the help of an advisory committee, such as the one we used for the 2015 HRBS, survey content could be streamlined. DoD and the Coast Guard could also consider developing official policy about what should, and should not, be included in the survey content.

Send survey invitations from a .mil account to address information technology issues. Given our issues with blocked emails and blocked content within emails (e.g., the web link to the survey), future iterations of the HRBS should explore whether it is possible and advisable to send survey invitations from a .mil email address. Although this seems like an easy fix, it could have implications for how respondents view the security of their personal data. If respondents believe that a survey request for highly sensitive information coming from a military email account will lead to loss of anonymity or confidentiality, response rates and quality may deteriorate. A thoughtful analysis of the costs and benefits for using a military email address should be undertaken prior to the next iteration of the HRBS.

Explore options to contact nonresponders (confidential versus anonymous survey). Switching from an anonymous survey to a confidential one would allow for targeted nonresponse messages. That is, it would be possible for the survey contractor, but not DoD or the Coast Guard, to know who has and has not completed the survey. The 2015 HRBS used up to nine generic email and four postcard reminders. These were often viewed as annoying to participants, especially if they had already completed the survey. Survey-method research has shown that personalized invitations to web-based surveys improve response rates. A confidential survey could also offer DoD and the Coast Guard information on what types of individuals are more or less likely to complete surveys and allow for survey weights to better account for nonresponse among certain subgroups. Future iterations of the HRBS could use both an anonymous and a confidential approach in order to assess which yields the highest response rates and data quality.

Consider offering incentives. A final consideration for future HRBSs is to offer an incentive, either as an enticement before completion (e.g., receiving $2 with an invitation to take a survey) or as payment after completion. Assuming any regulatory issues can be addressed, offering incentives for survey completion may improve response rates. Survey-method research clearly shows that incentives improve response rates. Incentives could also be combined with a confidential survey in order to target nonresponders or demographic groups for which response rates are low.