Short abstract

Since 2010, RAND has worked with the Kurdistan Regional Government to improve its health care system. This phase focused on a primary care management information system, physician dual practice reform, and patient safety training.

Keywords: Health Care Financing, Health Care Organization and Administration, Health Care Services Capacity, The Kurdistan Region-Iraq, Patient Safety, Physicians, Primary Care

Abstract

Since 2010, the RAND Corporation has worked with the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Planning of the Kurdistan Regional Government to develop and implement initiatives for improving the region's health care system through analysis, planning, and development of analytical tools. This third phase of the project (reflecting work completed in 2013–2015) focused on development and use of a primary care management information system; health financing reform, focusing on policy reform options to solve the problem of physician dual practice, in which physicians practice in both public and private settings; and hospital patient safety training within the context of health quality improvement.

Most main primary health care centers serve too many people, and most sub-centers serve too few people. Staffing by physicians, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists is uneven across the region. The data also identified centers where laboratory, X-ray, and/or other equipment should be repaired or replaced and where users should be trained. Though the required workweek is 35 hours, and all physicians are paid for these 35 hours, most physicians spent only three or four hours per day working in the public sector. The remainder of the time was often spent working in the private sector, where pay is much higher. The vast majority of physicians (over 80 percent) indicated that if pay were higher and public-sector resources were increased, they would prefer to work only in the public sector. To resolve the problems associated with dual practice, the authors recommend full separation between public- and private-sector practice.

Introduction

Since 2010, the RAND Corporation has worked with the Ministry of Health (MOH) of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) to develop and implement options for improving the region's health care system through analysis, planning, and development of analytical tools. Here we report on the activities in three distinct areas related to health and health care selected by the MOH and the Ministry of Planning (MOP) as priority areas. The areas of work are independent, but each contributes to laying the foundation for change through formative data development, policy and organizational reform options, training, and/or technical assistance.

This third phase of the RAND health sector project (reflecting work completed in 2013–2015) focused on:

development and use of a primary care management information system

physician dual practice within the context of health financing reform

hospital quality training.

Earlier reports (Moore et al., 2014; Anthony et al., 2014) described the KRG health care system—including primary care, health financing, and workforce projections—and presented initial analyses of the areas covered in more specificity here.

Primary Care Management Information System

Background

In the first phase of the RAND Health project (2010–2011), we comprehensively examined the KRG's primary health care system and offered nearly 60 specific recommendations, which we classified by degree of importance and feasibility. One of the most important and feasible recommendations was to establish a management information system (MIS) to monitor resources and services at primary health care centers (PHCs). Such a system would help managers monitor the location, staffing, equipment, and services at PHCs across the region and identify problems that require management attention. During the second phase (2012–2013), we developed and helped pilot such a system. During this third phase (2013–2015), we facilitated the collection of more complete data from all PHCs, analyzed those data, and identified a number of problems that warrant management attention related to population coverage, staffing, equipment, and services. This study describes the data collection efforts and focuses on the analyses and their implications.

Results from Most Recent Round of Data Collection

The effort to collect a new round of updated and more complete MIS data for 2013–2014 began in September 2013. Working with Kurdish-speaking MOH counterparts, the RAND team convened a half-day meeting with representatives from the health districts to orient them to the updated dual-language MIS form and made additional revisions to it based on their feedback. The information reflected on the form included basic information about the health center and detailed information on staffing (numbers and types), equipment and supplies, and services, as follows:

-

report information

health center name and identification code

date submitted

name and telephone number of person completing the form

-

basic information about the health center

jurisdiction: governorate, district, sub-district

location: Global Positioning System coordinates (latitude, longitude)

type of center (main PHC, branch or sub-center, family center)

catchment population

number of shifts per day (if two, whether public or consultation clinic)

-

staffing

total number of each type of staff: medical doctor (all), permanent general practice physician, rotating physician, specialist physician (by listed specialty), dentist, pharmacist, nurse (all, and by level of training), traditional birth attendant, midwife, laboratory technician, medical or prevention assistant, dental assistant, pharmacy assistant, service staff

center director (physician, assistant, or other)

-

equipment and supplies

number of beds

computer: number, functional status, trained user, number of users, type of use (statistics, administrative functions, pharmacy, other), Internet connection

laboratory equipment—presence, functional status, and presence of a trained user for each: microscope, centrifuge, autoclave

diagnostic equipment—presence, functional status, and presence of a trained user for each: ultrasound/sonogram, electrocardiogram (ECG), non-dental X-ray, dental X-ray, dental chair, dental tray

ambulance

-

services

medical/nursing—core services: child growth monitoring (and follow-up), vaccination (and follow-up), oral rehydration (packets, on-site administration), antenatal care (and follow-up)

medical/nursing—chronic diseases: hypertension (screening, management), diabetes (screening, management), mental health (screening, management)

medical/nursing—other: labor and delivery, family planning, health education, health visitor

dental: any dental services at center, type of dental service (restorations, simple extractions, procedures [e.g., dentures])

diagnostic: any laboratory service; specified tests from blood, urine, stool

pharmacy: basic essential medications or more than basic medications provided

organized referral system: referral out, referral feedback to primary care center.

The revised form was transmitted to the District Managers in early November 2013 to begin data collection. In December 2013, RAND met with the Directors-General for Health in Duhok, Erbil, and Sulaimaniya (commonly known as Suli) to ask for their assistance in completing the data collection process in a timely manner. Data collection took several months, and final data were received by early October 2014.

This study reflects MIS data submitted for 605 centers, including 127 centers in Duhok, 180 in Erbil, and 298 in Suli. About one-third of the centers are main PHCs, and two-thirds are sub-centers. Mapping data were available for 532 (88 percent) of the 605 centers.

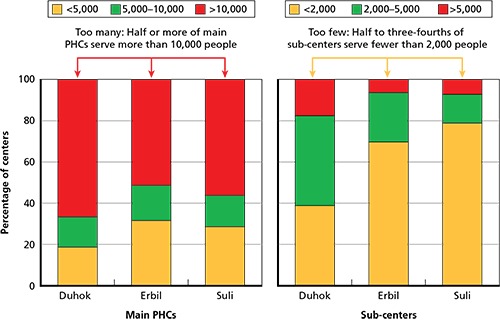

Population coverage. Based on World Health Organization (WHO) recommended standards of two or three centers per 10,000 population, most of the KRG's main PHCs serve too many people (more than 10,000), and most sub-centers serve too few (fewer than 2,000), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Catchment Population Size for Main PHCs and Sub-Centers

Staffing. Most main PHCs have at least one physician (100 percent of centers in Duhok and more than 80 percent in Erbil and Suli), typically more than one; but very few sub-centers (fewer than 20 percent in each governorate) have a physician, typically. About half of the main PHCs that have a physician also have a rotating general practitioner (GP). Main PHCs also have more nurses than sub-centers (an average of 13.0, with a range of 7.1 to 17.2, compared with an average of 2.5 nurses per sub-center, with a range of 2.4 to 2.8). The training level of nurses differs across the three governorates. In general, nurses in Erbil's main PHCs and sub-centers are better trained than their counterparts in Duhok or Suli—a higher proportion of Erbil nurses have formal nursing school training. In addition to nursing staff, about one-fourth of main PHCs have a midwife or trained birth attendant—2 percent of main PHCs in Duhok and 29 percent each in Erbil and Suli.

Compared with nearly universal physician staffing at main PHCs, only about one-half to two-thirds of main PHCs across the three governorates have a dentist. Of greater concern is the significant mismatch between dental staffing and dental X-ray equipment, especially in Duhok, and the indication that some centers in Erbil and Suli have dental X-ray equipment that is not functional and/or has no trained user. Mapping of individual centers indicates those with such mismatches. These maps can help district and governorate health authorities identify and remedy operational problems. Finally, relatively few main PHCs have a pharmacist. Only in Erbil do most main PHCs have a pharmacist (about 80 percent), compared with about 30 percent in Suli and about 10 percent in Duhok. Nonetheless, most main PHCs provide just basic medications, and some provide more than basic medications. PHCs without pharmacists draw on pharmacy assistants or other personnel to dispense medications.

Equipment. Nearly all main PHCs have a computer, and nearly all computers are functional. However, a significant number of centers that have a functional computer do not have a trained user, presumably rendering the equipment less than fully useful. This gap is especially true in Erbil. Nearly all main PHCs also have basic laboratory equipment: microscope, centrifuge, and autoclave. In main PHCs, most laboratory equipment is functional and has a trained user, with the exception of PHCs in Erbil. Most main PHCs also have ECG equipment, but far fewer have sonogram equipment. Most of this equipment is functional and has a trained user. Fewer main PHCs have X-ray equipment, but most X-ray equipment is functional and has a trained user.

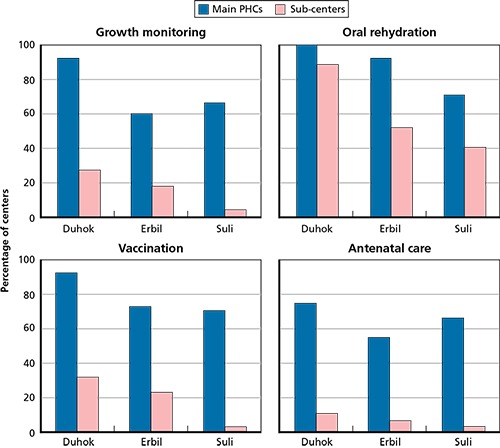

Core primary care services. Most main PHCs and some sub-centers provide some—but not all—of the four core primary care services of child growth monitoring (GM), oral rehydration salt (ORS) packets and on-site treatment, vaccination (VAX), and antenatal care (ANC), as well as basic health education (Figure 2). All main PHCs and sub-centers should be able to provide at least GM, VAX, ORS, and health education. Of these core services, ORS is the one most commonly available at sub-centers.

Figure 2.

Core Primary Care Services Provided at Main PHCs and Sub-Centers

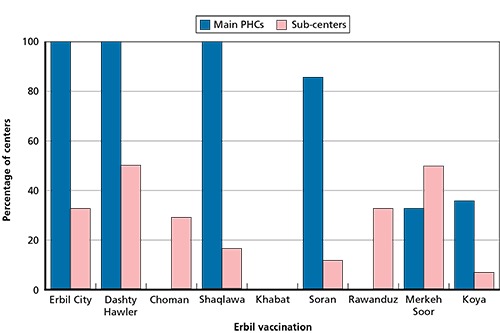

Governorate-level information provides a general picture but may not be directly actionable. Figure 3 shows the proportion of Erbil centers that provide vaccination services at both the governorate and district levels. Departments of Health (DOHs) can use district-level information, as well as information on specific centers (presented in map format), to help target improvements at individual centers. Using vaccination coverage as an example, the Erbil DOH could look at district-level information and may wish to focus on improving these services at main PHCs in the Merkeh Soor and Koya districts in particular, as well as in sub-centers throughout the governorate. The Director General of Health could look at center-level information (in either map or table form) to identify specific centers that warrant management attention.

Figure 3.

Vaccination Services Provided at Main PHCs and Sub-Centers in Erbil, by District

Other primary care services. Most main PHCs provide screening and management of hypertension (HT) and screening for diabetes (DIAB). Many main PHCs also provide DIAB management. Some, especially in Duhok, also provide mental health (MH) screening and management. About half of the sub-centers in Erbil and Suli, but fewer in Duhok, provide HT screening and/or management; fewer provide DIAB screening or management; and virtually none provides MH screening or management. MH services are relevant to addressing past trauma (experienced by torture survivors in the region) and current stressors, including the needs of the refugees and other displaced persons, whose numbers grew significantly during 2013–2014.

Operations. About half of the main PHCs in Duhok and Suli operate one shift per day. The other half operate two or three shifts per day. Nearly all sub-centers operate just one shift per day. Many centers have an ambulance; MIS maps can help inform the optimal distribution of current and new ambulances. Finally, referral systems are a critical component of effective primary care systems. Centers must be able to track patients referred out for testing or specialized services and receive feedback at the center. Many main centers have a system for referring patients out, but not for receiving information back. Even more concerning is that most sub-centers do not have any referral system. The shortfall in patient referral systems warrants management attention.

Conclusions

The MIS data offer important insights about the location and status of PHCs, staffing, equipment, services, and operations across the Kurdistan Region—Iraq (KRI). They are useful for monitoring progress, identifying opportunities for improvement, and tracking improvements made. Although the geographic information system (GIS) data were also fairly robust, the maps suggest that reporting was incomplete from several districts in the Erbil and Suli governorates. While listings of characteristics for individual centers can be presented as tables, the maps may be more visually appealing and readily grasped; therefore, we believe that capture of GIS data for all centers is warranted to enable presentation of data in map format.

Most main PHCs may serve too many people, though the centers serving larger numbers of people have, on average, more doctors and nurses than those serving smaller populations. Most sub-centers serve too few people, based on international standards. This information regarding supply and demand at main PHCs and sub-centers can be used to plan for additional staffing, new centers, and/or upgrading of sub-centers to main centers in areas where centers serve too many people and, potentially, to consolidate sub-centers that serve too few people.

Staffing by physicians, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists is uneven across the KRI. Health leaders should consider feasible opportunities to improve staffing patterns, including, for example, upgrading nursing skills, better use of nurses, more assistants to help enhance the efficiency of doctors, and/or other viable solutions. It will also be important to correct mismatches between dental staffing and dental equipment so that dentists at centers have the equipment they need to provide services. The MIS data also identified centers where laboratory, X-ray, and/or other equipment should be repaired or replaced and where users should be trained.

KRI primary care main centers and sub-centers serve as a foundation for providing world-class core primary care services, as well as some chronic disease screening and management. The MIS data have identified areas of success at all centers, as well as opportunities to fill gaps in services provided. Filling such gaps seems feasible. Also important is the potential for the MIS to help inform emergency preparedness and response planning and to track services provided in areas where large numbers of refugees and other displaced persons have arrived. Effective referral systems and appropriate distribution of available ambulances will further strengthen the KRI's primary care services and are a cost-effective means to achieve better health outcomes for all persons served.

Finally, it will be important to institutionalize the MIS within the KRG so that it becomes a tool used by managers at all levels to monitor PHCs, staffing, services, equipment, and operations throughout the KRI. This includes primary health care programs carried out in collaboration with various partners, such as WHO, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the World Bank. We recommend outsourcing the development of an online system that can be accessed by all appropriate officials, including the DOHs in the three governorates, the central MOH and MOP in Erbil, and relevant primary care partners. The system should be user friendly. It should be easy to access so that all appropriate users are able to enter updated data and generate tables, graphs, and maps. As such, it promises to be a simple yet powerful tool to help manage a foundational component of the KRG's overall health system.

Health Financing Reform: Dual Practice

Background

During Phase I (2010–2011), we identified dual practice (DP) as a policy challenge that substantially affects the efficiency and effectiveness of health care delivery. Dual practice refers to situations in which physicians work part of their time in the public sector and part in the private sector. In Phase II (2012–2013), we laid out general financing reform options and analyzed the policy approaches that could be taken to address the DP issue. In this third phase of the project (2013–2015), we conducted focus group discussions and interviewed a wide range of physicians regarding DP. Our goal was to develop specific policy options that would enable the KRG to adopt and begin to implement changes to address DP in the near future, given present data and managerial capacity. Overall, the analysis suggests practical, implementable changes that can improve the efficiency of the government sector while also expanding the amount of services available overall to the public.

Almost all KRI physicians choose to work in the private sector as well as the public sector once they reach consultant status. Most then engage in private-sector work in their own private clinics and/or in the rapidly growing number of private hospitals and surgical centers. Physicians are almost always paid for private-sector services in cash at rates that greatly exceed public-sector fees for comparable services. Because there is almost no private health insurance coverage, these fees are paid directly by the patients and/or their families. However, people who can afford the higher fees have been willing to pay for and receive care in the private sector because they believe that they get care more rapidly and that doctors will see them for more time, pay greater attention to them, and provide better follow-up.

Policymakers have expressed concern about DP. The fact that patients are willing to pay for care in private clinics suggests that access to care in the public sector, which is almost free, is at capacity and/or that the quality of care is worse and waiting times are longer than in private clinics—or, at least, that the population perceives this to be so. We have previously estimated that without reforming DP, within ten years there will not be enough skilled physicians practicing in the public sector for the number of hours that will be required to fulfill the constitutionally guaranteed right to health care (Moore et al., 2014; KRG, MOP, 2013).

Furthermore, the DP situation in the KRI is resulting in the highly inefficient use of limited resources in the public sector. Currently, physicians are supposed to work 35 hours per week in the public sector, but most actually work only a fraction of that. However, they get paid a full salary no matter how many hours they actually work. It is well known that most physicians work far fewer than the required number of hours per day before departing to their private clinics. Physician compensation is adjusted for rank and seniority, but compensation is not related to the amount of time worked, the quality of work, physician specialty, or physician productivity. Physicians receive extra compensation for teaching in a medical school.

KRG health policy leaders recognize that DP is not only unsustainable and inefficient, but also that its existence makes health financing reform, a key KRG policy objective, very difficult to achieve. In Kurdistan Region—Iraq 2020: A Vision for the Future (KRG, MOP, 2013, p. 7), the KRG lists the introduction of “a sound health care financing system” as a key priority. The document goes on to say that to achieve a sound financing system, the KRG needs to “develop and implement a policy that pays for physician services based on the amount and quality of the services they provide” (KRG, MOP, 2013, p. 7).

Policy Challenges and Constraints

KRG decisionmakers seeking to address the DP issue face a number of challenges and constraints specific to dual practice, including:

Data: Very few data are routinely collected or made readily available for decisionmaking. In the public sector, no data are routinely collected on the number of hours that individual physicians spend delivering care, the number of patients seen by physicians or the number of procedures that they perform, or the quality of the care that they deliver. Because the financing system is budget-based, no payment or reimbursement data exist that measure the volume of services provided by a physician.

Regulatory capacity: The regulatory system required to address physician DP reform is considerable. However, the current ability of the MOH to regulate the health care system is limited by the lack of trained staff, resources, and existing regulatory systems.

Hospital management: Hospitals are usually managed by prestigious physicians who are rarely trained in management. Hospital managers have little authority over staffing, budgets, or hiring. They cannot reward or penalize physicians for the amount of time they work or for their performance.

Funding: Effective long-run change almost certainly cannot be achieved without significantly increasing public budget allocations so that physician pay can be raised to a level to be competitive with the private sector and to enable investments in other needed inputs and ancillary services. These investments in additional infrastructure (e.g., examining and operating rooms) and ancillary services are necessary for physicians to be able to work longer hours. Budgetary flexibility is already extremely constrained as the KRG deals with sporadic budget payments from Baghdad along with the demands of defending itself against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) threat, which must take priority.

Physician Focus Group Data

To supplement preliminary discussions with physicians in the fall of 2013, RAND conducted six focus groups with about 150 physicians during the week of December 8, 2013. The focus groups were designed to gather information about physician conduct and preferences related to working in both the public and private sectors. We conducted two focus groups in each of the three main governorates—Suli, Erbil, and Duhok. In each governorate, we sought to talk to senior house officers and consultant physicians. As we anticipated, the younger physicians (senior house officers) generally did not practice in the private sector, while almost all consultants had their own private offices and/or worked in private hospitals. Many consultants were also medical university faculty. The participants spoke candidly and seemed to appreciate being given the opportunity to provide input into the policymaking process. We learned the following from these focus groups:

Required workweek: Like all public employees, physicians are expected to work 35 hours per week. Because most physicians work six days a week, the 35-hour requirement has come to mean working from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. five days per week with additional on-call hours. Most physicians are also on call about three days each month for 24-hour periods. Hours for emergency physicians are quite different.

Time actually worked in the public sector: We asked focus group participants how much time they spend in the public sector before heading either to private practice or to a consultant clinic. Answers varied, but, in general, participants said that they spend about four hours per day in the public sector. When asked the same question, senior house officers, who are relatively new physicians still in training, responded that although there was a range, most consultant doctors who are more experienced and senior than the house officers spend fewer than three hours a day in the hospital before leaving for their own clinics. Indeed, some physicians are reported to spend an hour or less in the public hospitals, and some show up for public-sector duty only occasionally. All focus group physicians agreed that on average the older, more experienced, and better known a physician is, the less time he or she is likely to spend in the public sector. It also appeared that, on average, specialists spend less time in the public hospitals than do their GP colleagues. In short, over half of the salary paid to physicians is for work they never perform, which is a highly inefficient use of resources.

Primary reason for working in the private sector: Almost universally, the first reason participants cited for engaging in DP was the need to make enough money, since public-sector pay is not sufficient to sustain their families. Everyone knew physicians could make many times their public salary in the private sector and/or by working in consultative clinics. We did not try to ascertain this differential in pay, but focus group comments suggest that it varies significantly by specialty and individual physician.

-

Secondary reasons for working in the private sector: Other reasons included the following:

Public facilities and equipment needed to enable longer public-sector hours are inadequate (e.g., inadequate office space, beds, and laboratories).

Public ancillary services are not available all day, making extended practice difficult.

Patient loads per hour are too heavy in the public sector to provide proper care but are much lighter in the private sector.

Public-sector nursing staff are inadequate, poorly trained, and lack motivation and skills.

We asked focus group participants to suggest ways to improve public-sector hospitals. Not surprisingly, their answers mirrored the reasons described for choosing to engage in DP, including better nurses, improved laboratories, reduced patient loads, more hospital beds, more examining rooms, reliable availability of medicine, adoption of an appointment system, creation of job descriptions, better referral systems and records systems, and longer hospital operating hours.

Requiring a public service period before private practice: We elicited participants' views on requiring physicians to work a specific period of time in the public sector before private-sector practice was permitted. Physicians were willing to accept this as a policy change and thought that the policy would result in better trained and able physicians when they were eligible to treat private patients. This was true of both senior staff who would not be affected and house staff who would be affected if the policy were in place today.

Compensation levels: We asked participants in the six focus groups what level of compensation would be necessary to motivate them to work more in the public sector. Answers varied by location, specialty, and seniority. The range of answers was very large, but it always involved a significant increase in compensation. Physicians often played off of each other. For instance, if an internal medicine specialist wanted a salary of $8,000 a month, a surgeon—viewing himself as worth more—would respond with a number like $10,000 a month. Indeed, the physicians from our interviews and focus groups seemed to think that a surgeon's pay should be about $10,000 a month or higher. There was general frustration about the fact that all specialties were paid about the same and that physicians who saw more patients, worked harder, and worked longer hours were not rewarded monetarily.

Most physicians reported that they would prefer to work more than 35 hours per week and earn more pay through the public sector. The vast majority of physicians (over 80 percent) indicated that if pay were higher and resources were available to enable them to do their jobs, they would prefer to work only in the public sector because (1) they viewed public-sector care as being of higher quality in the sense that it offered a full range of services, which is not the case in most private clinics or even in private hospitals, which are usually similar to outpatient surgical centers, and (2) they sought a better work-life balance. This point was made across all focus groups across all three governorates, independent of the seniority of the group.

We looked in some detail at the case of GPs, who represent the largest number of physicians. Present GP salary levels were approximately $1,200 per month, for which they were working approximately 15 hours per week (60 hours per month). We also discovered that incentivizing GPs to work the required 35 hours weekly (144 hours per month) would necessitate paying them $2,000–3,000 per month ($2,500 on average, according to consultants and house officers alike). Many physicians said that they preferred to work longer hours (e.g., 40–50 hours per week) for even higher salaries (e.g., to $4,000–5,000 per month for GPs).

Using the numbers above, we can estimate the supply curve for GP services and calculate on average how much the budget for GPs in the public sector would have to increase to staff hospitals at current levels. If monthly salaries were raised to $2,500, GPs would be willing to work a full 35 hours per week; this is roughly double the amount they are now being paid, for which they would be willing to work roughly double the amount of time they now work in the public sector. If this policy were instituted and all else was constant, public facilities would require only half as many GPs as currently employed, each of whom would work about double the amount of time they currently work. However, the MOH would have to raise GP salaries.

To better understand the budget effects, we varied the salary needed to induce a GP to work a full 35 hours ($2,500 to $2,750) and calculated MOH budget increases needed for GP services to staff facilities at current levels. At a $2,500 monthly salary, the overall budget for GP services would need to rise by only a modest 4 percent; in contrast, the GP services budget would need to rise by 14 percent if salaries were raised to $2,750.

This exercise illustrates the following:

The increase in budgets needed to achieve efficiency is much less than currently thought, since inefficiency is eliminated as the number of GPs employed is reduced.

The needed budget increases are very sensitive to the amount of increase in GP salaries.

A larger and more formal survey of physician preferences is needed for precise calculations.

We note that the salary increases needed to achieve 35 hours of work from GPs are much smaller than those for specialty groups like surgeons, who demanded much higher pay than GPs. Today, surgeons are, on average, working fewer hours than GPs. Thus raising GP salaries would also necessitate an even larger percentage increase in the budget for surgeons and other specialists.

We also learned from the focus groups that presently there are not enough examining rooms, hospital beds, or ancillary services to enable physicians, including GPs, to work the 35 hours they are supposed to work. The lack of resources varies by facility.

In sum: Physicians reported that they would prefer to work exclusively in the public sector if they could receive a higher salary and if resources necessary to do their jobs were available, despite the fact that the higher public-sector salary would still be lower than the salary they could earn in the private sector. It seems clear that the MOH could match its present manpower hours worked with fewer physicians each working longer hours, and end up with a more efficient system. In implementing these changes, policymakers will need to coordinate changes in hospital resources necessary for physicians to work longer hours, such as beds, ancillary facilities, and other services necessary.

Policy Options

Decision criteria: Before exploring the best policy options open to the KRG, we developed decision criteria against which to judge options, whether in isolation or in combination with other policies. Key criteria should include the degree to which the policy helps achieve KRG's national health care objectives—that is, the policy

is easily implemented

minimizes regulatory complexity (i.e., increases feasibility)

ensures equity (e.g., does not promote a two-tiered health care system)

is efficient

minimizes public budget outlays

ensures adequate supply of high-quality physician services in the public sector

promotes improvements in the quality of care.

Options: We used these criteria and developed four feasible policy options (see Table 1). All of the options also include a policy that requires physicians to work a certain number of years (e.g., three to five years) in the public sector before private sector work is allowed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Policy Options

| Option 1: Let the Market Evolve | Option 2: Link Time Worked to Compensation to Incentivize Physician Behavior | Option 3: Separate Daytime Practice but Allow Evening Private Practice | Option 4: Separate Public and Private Practice Completely | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three to five years of public service required before work in the private sector is allowed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Decisionmaker in control | Physician | Physician | MOH* | MOH* |

| MOH controls number of physicians working in the public sector | No | No | Yes* | Yes* |

| Physicians working required hours set by MOH receive bonus during phase-in period | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Work in private sector allowed after completion of daytime public service | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Locks physicians who choose public service in this choice for a significant time (e.g., three to five years) | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| To work the option would require MOH to raise the standard workweek to approximately 40–50 hours | No | No | No | Yes |

| Easy to implement and administer | Yes | No | Mostly | Yes |

| Captures wasted resources in the present system | No | Some | Yes | Yes |

| Would reduce public pension payouts for time not worked | No | Requires policy change | Yes | Yes |

| Would likely result in two-tier care | Yes | Yes | Less so | Less so |

Physicians choose whether to work in the public or private sector and are locked in for a number of years. The MOH is the actual decisionmaker because it sets the number of physicians it allows to work in the public sector even if more physicians desire to do so.

Option 1: Let the market evolve. This approach would allow the market to evolve as it is today without direct policy intervention.

Option 2: Link time worked to compensation to incentivize physician behavior. This option introduces incentives to get physicians to choose to work the full 35 hours required (or some other number of hours, as determined by the MOH) but leaves the decision on whether to work in the private or public sector to the physician. There is no clear separation between the public and private sectors, and physicians are not locked into either one. In this option, after a phase-in period of three to four years in which physicians would receive increasing bonus amounts if they worked the full weekly number of hours required by the MOH, the bonus would be included in physician base pay rates only for those physicians who worked the full standard number of hours set by the MOH. Bonus and pay rates would be calculated by specialty.

Option 3: Separate public and private practice during the day but allow evening private practice. In this option, physicians choose to work either in the public sector or the private sector during the day. Physicians who choose the public sector are locked into that choice for a number of years (e.g., three to five years) but can choose to have a private practice in the evening after a full public-sector workday. Once each year, physicians who choose the private sector will be offered an opportunity to join the public sector if they wish. Such a policy will simplify administration and will also enable the MOH to better plan and budget for the future. Salary rates would be set separately by specialty, and the standard number of hours of work per week would be set by the MOH. The number of physicians hired in the public sector and the hours they would be required to work would be specified by the MOH.

Option 4: Separate public and private practice completely. This option requires a physician to choose to work exclusively in either the public or private sector and, if he or she chooses the public sector, to lock himself or herself into that choice for a significant length of time (e.g., three to five years). Pay rates would be set separately by specialty, and the standard number of hours of work per week would be set by the MOH. The number of physicians hired in the public sector and the hours they would be required to work would be specified by the MOH.

No matter what policy option is chosen, we recommend phasing in the changes to achieve maximum impact and minimal disruption to care. We have laid out the phased introduction for each option in detail. The two preparatory phases envisioned are summarized below:

Phase 1 (Year 1): Prepare for Policy Change. Phase I would involve agreeing on the details of policy change; working with affected groups, such as doctors, to gain support; and beginning to collect the data necessary to manage the selected policy option(s).

Phase II (Years 2–4): Reform Policy. The details of Phase II vary depending on which option is selected, but in all cases this phase would involve raising physician salaries in steps over time as bonuses that would be paid only if physicians worked the required hours decided on by the MOH. During this phase, increases in capacity in terms of beds, ancillary services, and other requirements would be made in coordination with changes in physician hours.

Conclusions and Recommendations

We believe that all the options described above, with the exception of Option 1, would improve the financing system and efficiency of the KRG health system. Option 2 would lead to minimal improvements and would retain considerable inefficiencies in planning and budget. After evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of all options, we recommend Option 4, which implements a full separation between the public and private sectors. In this option, physicians choose to work in only the public or private sector, with no private practice allowed in the evening for those who choose public service. This option will eliminate waste, is easier to implement than the other reform options, and is flexible and adaptable to changing needs over time. Option 3, in which private practice is also allowed in addition to public service, runs the risk of doctors not complying and working more in the private sector, as well as continuing the abuse of referring public-sector patients to their own private practices.

We strongly caution that any plan should be phased in and coordinated so that the necessary inputs (facilities, medicines, and ancillary services) are available for physicians to do their work. Appropriate government funding and a willingness to enforce compliance will be required.

Creating a Sustainable Health Quality Infrastructure

Background

The KRG MOH and MOP are committed to modernizing the KRG health care system and to moving KRG health care in the direction of a world-recognized health care delivery system. To that end, one specific long-standing objective has been to begin building a quality infrastructure to support residents' health care expectations.

During the third phase of its support to the MOH, RAND provided training and support to advance the quality and patient safety agenda. This training was envisioned as a starting point for building the quality infrastructure throughout the region. Further, program trainees, armed with the appropriate skills and motivation, provide a workable and sustainable strategy for promulgating the quality agenda, sharing successes, and training teams from other facilities to advance quality improvement throughout the region.

RAND explored several different approaches to quality assessment and improvement to use as a framework for the training program. We considered the following dimensions when selecting the approach:

comprehensiveness with respect to the breadth of health care activities in the KRI

the general acceptability of the approach in other settings in which it was applied

the use of a similar approach in nearby countries and by respected facilities in those countries

the availability of expertise to train and mentor Kurdistan colleagues on aspects of the approach

evidence that the approach was achievable and sustainable.

RAND selected the approach to quality used by Joint Commission International (JCI) as the basis for our training. JCI's approach has been implemented in a number of nearby quality health care facilities (e.g., in Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar). Further, a number of respected consultants with Middle East experience work with or have worked with JCI. JCI standards are recognized worldwide as a standard for hospital and health system quality. Importantly, it would be possible to use JCI standards as a framework for teaching quality and planning a stepwise approach that has the potential to ultimately lead to accreditation.

RAND was sensitive to issues and challenges faced by the KRG health care system. The region has many talented and dedicated people and a long history of excellence in education and health care. Devastated by the prolonged political Iraqi conflict over the previous decade, the region's advancement had been arrested, and facilities have decayed. Professionals were unable to advance their knowledge and careers. However, they retained their passion for returning the KRI to its place among the world's great peoples, an institutional memory of what was, and a strong vision for what the region and its medical system could again become. It was important, therefore, to select a system that could be modified so as to make stepwise progress toward meeting (or exceeding) all international standards, rewarding participants for incremental success in what would become a continual pursuit of excellence in health care.

Adopting the JCI framework for quality carried the potential for individual facilities to achieve internationally recognized accreditation as an affirmation of their commitment to quality without establishing the expectation that all facilities would meet those standards within a very short time frame. That is, stepwise progression toward meeting all standards should be rewarded, and those undertaking that effort must not be considered to have failed by not immediately meeting all standards.

The Initial Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Education Program

The goal of the initial quality endeavor was to create enthusiasm for advancing quality of care in KRI hospitals and to identify a group of quality leaders with the skills and demeanor necessary to propagate the quality agenda. To that end, it was important to identify individuals with sufficient authority and respect within their organizations such that there would be local traction for programs developed and deployed.

The KRG identified a delegation of eight senior leaders from the MOH and representatives from public hospitals from throughout the KRI to participate in a 3.5-day customized education program in Istanbul, Turkey, on February 23–27, 2014. This interactive and experiential program was organized and presented by RAND consultants in collaboration with Acibadem Hospitals Group, a private hospital system based in Turkey. Acibadem was selected as the training site because of its established quality reputation and its interest in knowledge-sharing.

The education program included a combination of didactic presentations, videos, case studies, small-group problem-solving exercises, larger group discussion, and evaluation demonstrations in a variety of patient care units. Acibadem Hospitals Group staff also shared their “quality journey.” Participants received a workbook that included all presentations and a copy of the Joint Commission International Accreditation Standards for Hospitals, 5th Edition (JCI, 2015), which became effective for accreditation surveys beginning April 1, 2014. The participants were very engaged, interested in the material, and eager to translate their learning into actual practice in KRG public hospitals.

On the last day of the education program, the content focused on change management and how the participants could begin to pilot specific quality and safety interventions, such as hand hygiene, in Kurdish public hospitals. The presentation began with a quote from the KRG health leaders themselves, made earlier in the training session: “Change begins with just one step. We must begin.”

Using an established methodology for change management, the group members established the following plan for pilot quality and patient safety improvement at their individual hospitals over the ensuing six months:

Step 1: Creating a Shared Initial Set of Improvement Opportunities

infection control (hand hygiene)

identification of patients

emergency cart standardization

safe surgery protocols

completeness and standardization of medical record.

Step 2: Shaping a Vision

improved health care through adoption of international best practices for quality and safety

Step 3: Mobilizing Commitment

support of Ministries of Health, Education, Planning, and Finance

support of community leaders (e.g., religious leaders, political leaders)

support of the media in recognizing quality efforts by leading centers

support of clinical leaders, junior doctors, ancillary health care personnel, and medical and nursing associations.

Step 4: Making Change Last

Step 5: Monitoring Progress

Progress on Implementation of Improvement Priorities

Since the training program, the KRG has been challenged with pressing health issues related to outbreaks of military conflict and an influx of refugees. Despite these challenges, significant quality and safety improvements have been implemented in at least one of the participating hospitals, West Erbil Emergency Hospital.

The hospital director, Dr. Lawand Hamid Meran, reported that despite the difficulties faced by his and other Kurdish hospitals in the 2014, he and his hospital team focused on:

implementing a system for correct patient identification

implementing available equipment, supplies, and processes for hand hygiene

demonstrating infection control improvement

fostering improved communication between doctors, staff, and patients

instituting monitoring systems for the improvements above through use of trained observers.

Creating Momentum for the Future

The knowledge and attitude of the participants at the training session and the impressive improvements implemented by West Erbil Emergency Hospital and by others following the session confirm that a new, higher-functioning and higher-quality health care system in the KRI is possible. Therefore, RAND recommends that the MOH further build capacity in quality improvement and patient safety throughout the region's public health sector. RAND also recognizes that political conflict since the training has impeded the ability of very dedicated individuals to achieve the successes that are clearly possible. It will be necessary to help initial participating institutions reengage to the extent necessary while simultaneously working to expand regional participation.

One approach to such capacity-building is the development of a regional Quality and Patient Safety Institute based in Erbil that would use a train-the-trainer methodology. Hospital directors who have already demonstrated a commitment to leading quality and safety improvements should serve as co-faculty for future training, ultimately transitioning most if not all training to Institute staff.

Conclusion

RAND has continued to work with the KRG MOH and MOP to improve the KRG health system and help achieve the government's vision for the future. During the third phase of this project (2013–2015), we helped to implement the primary care MIS, presented options for addressing the problem of dual physician practice, and carried out initial training for health care quality and patient safety.

Notes

The research described in this article was sponsored by the Kurdistan Regional Government and conducted by RAND Health.

References

- Anthony C. Ross, Moore Melinda, Hilborne Lee H., Mulcahy Andrew W. Health Sector Reform in the Kurdistan Region—Iraq: Financing Reform, Primary Care, and Patient Safety. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation and Ministry of Planning of the Kurdistan Regional Government; 2014. RR-490-1-KRG. As of January 15, 2017: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR490-1.html. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdistan Regional Government, Ministry of Planning. Kurdistan Region—Iraq 2020: A Vision for the Future. September 2013.

- Moore Melinda, Anthony C. Ross, Lim Yee-Wei, Jones Spencer S., Overton Adrian, Yoong Joanne K. The Future of Health Care in the Kurdistan Region—Iraq: Toward an Effective, High-Quality System with an Emphasis on Primary Care. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation and Ministry of Planning of the Kurdistan Regional Government; 2014. MG-1148-1-KRG. As of January 15, 2017: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG1148-1.html. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]