Abstract

Objective

Susceptibility MRI may capture Parkinson's disease (PD)-related pathology. This study delineated longitudinal changes in different substantia nigra (SN) regions.

Methods

Seventy-two PD patients and 62 Controls were studied at both baseline and 18 months. R2* and quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) values from the pars compacta (SNc) and reticulata (SNr) were calculated. Mixed-effects models compared Controls with PD or PD subgroups having different disease durations: early (<1 year, PDE); middle (<5 years, PDM); and late (>5 years, PDL). Pearson's correlation assessed associations between imaging and clinical measures.

Results

At baseline, R2* and QSM were higher in both the SNc and SNr in all PD patients (group effect, p≤0.003). Longitudinally, SNc R2* showed a faster increase in PD compared to Controls (time×group, p=0.002), whereas QSM did not (p=0.668). SNr R2* and QSM did not differ between PD and Controls (time×group, p≥0.084), although both decreased longitudinally (time effect, p≤0.004). Baseline SNc R2* was higher in all PD subgroups (group, p≤0.006), but showed a significantly faster increase only in PDL (time×group, p<0.0001) that correlated with changes in non-motor symptoms (r=0.746, p=0.002). Baseline SNr QSM was higher in PDM and PDL (group, p≤0.002), but showed a longitudinal decrease (time×group, p=0.004) only in PDL that correlated with changes in motor signs (r=0.837, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Susceptibility MRI revealed distinct patterns of PD progression in the SNc and SNr. The different patterns are particularly clear in later stage patients. These findings may resolve past controversies, and have implications in the pathophysiological processes during PD progression.

Keywords: Substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), Parkinson' Disease, magnetic resonance imaging, quantitative susceptibility mapping

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is marked pathologically by dopamine neuron loss in the substantia nigra (SN) par compacta (SNc) of the basal ganglia.1,2 Increased iron in the SN also has been reported in postmortem studies of PD patients,3 a finding that was confirmed by some,4,5 but not all.6,7 In recent years, both R2* and the newer quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) measures have been used to estimate iron content in brain tissue, with the latter reported to be more sensitive.8,9 Of the two sequences, our companion paper10 confirms that in vivo QSM correlates better with iron content in postmortem brain tissue, whereas R2* may capture also other aspects of PD-related pathology, such as α-synuclein and possibly neuronal cell loss, in addition to tissue iron content. Several cross-sectional studies have demonstrated higher R2* and QSM in the SN of PD patients,11-14 and fueled enthusiasm for using these susceptibility MRI metrics to gauge PD progression. The results of limited longitudinal studies, however, have been inconsistent, with some reporting increased nigral signals,15,16 whereas others failed to detect a change17 or showed lower R2* in later stages of PD.17,18 These inconsistencies have shed doubt on the validity of using susceptibility MRI as a PD biomarker.19,20

It has been believed that neuronal loss and iron accumulation in PD are confined to the SNc rather than including the anatomically adjacent pars reticulata (SNr).1,21 Dopaminergic terminal loss is estimated to be 50-80% at the time of diagnosis and may continue to progress over the next five years, but eventually it “plateaus”,22,23 consistent with a first-order event24 based on radioligand studies following PD progression. A recent study, however, suggested that neuronal cell loss continues beyond five years.25 Clinical symptoms continue to progress over the disease course, especially after the “honeymoon” period (i.e., the first years after diagnosis),26 and include both motor and non-motor symptoms that have devastating consequences for patients. Although free-water diffusion MRI has shown promise as a progression marker in the early stages of disease,27 there currently are no validated biomarkers that can capture the dynamic, progressive nature of the disease in later stages (i.e., beyond five years).

The current study investigated R2* and QSM longitudinal changes in the SN (separated into the SNc and SNr) of a relatively large cohort of PD patients with different disease durations and controls. We tested the following hypotheses: 1) both R2* and QSM in the SNc, but not the SNr, will have PD-related changes; 2) the progression of R2* and QSM may depend on disease duration, particularly after five years. Here, we chose 5 years as a cutoff for later stage disease because putaminal dopaminergic fiber loss is believed to be complete by this time.2 Lastly, we explored the relationship between susceptibility MRI and clinical measurement changes over time.

Methods

Subjects

Seventy-two PD patients were recruited from a tertiary movement disorders clinic, and 62 controls were recruited from spouses and from the local community as part of a longitudinal study sponsored by the NINDS PD Biomarker Program. PD diagnosis was confirmed based on the UK Brain Bank diagnosis criteria.28 A follow-up study visit occurred 18.8 ± 0.8 months after the baseline visit. All participants were free of major medical issues or neurologic conditions other than PD. Demographic and clinical characteristics, the Movement Disorder Society Unified PD Rating Scales part I, II, and III (MDS-UPDRS-I, -II, -III); levodopa equivalent daily dosage (LEDD); the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA); the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS); and the PD Questionnaire (PDQ-39) were obtained from all participants at each visit, while patients were on optimized antiparkinsonian medications (ON state). PD subgroups [early stage PD (PDE), <1 year; middle stage PD (PDM), <5 years; and later stage PD (PDL), >5 years] were created based on time after first documented Parkinson's disease diagnosis as done previously.29 Detailed demographic data (for PD subgroups at the baseline and follow-up visits) are provided in Supplementary Table 1. All participants gave written informed consent that was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Penn State Hershey Institutional Review Board.

MRI image acquisition and analysis

At each visit, T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and multi-gradient-echo MR images were acquired on a 3T Siemens scanner. A magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo sequence was used to obtain T1-weighted images with repetition time/echo time=1,540/2.34 ms, field of view=256 × 256, slice thickness=1 mm (with no gap), and slice number=176. A fast spin echo sequence was used to obtain T2-weighted images with repetition time/echo time=2,500/316 ms and the same spatial resolution settings as T1-weighted images. T2*-weighed images were acquired by using a multi-gradient-echo sequence with 8 echoes (echo times ranging from 6.2 to 49.6 ms), and repetition time=55 ms, flip angle=15°, field of view=240 × 240, matrix=256 × 256, slice thickness=2 mm, slice number=64, and voxel size=0.9 × 0.9 × 2 mm3. All T1-weighted and T2-weighted images were inspected offline and deemed free of severe motion artifacts or any major structural abnormalities. R2* images were generated by nonlinear curve fitting of a mono-exponential equation (S(TE) = S0e−R2*TE), using the Levenberg-Marquardt approach. QSM images were generated using the morphology-enabled dipole inversion (MEDI) method with a nonlinear formulation of the magnetic field to source.30

Segmentation of midbrain structures

Three midbrain structures, the SNc, SNr, and red nucleus (RN), were segmented using an automatic atlas-based parcellation followed by manual correction (see Supplementary Figure 1). This semi-automatic approach was designed to improve the accuracy and repeatability of the segmentation, and consisted of four steps. Step 1: T1- and T2-weighted images from 20 randomly selected controls were used to construct an age-appropriate template using an unbiased atlas construction algorithm in the Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTS) package.31 The SNc, SNr, and RN were defined manually on the constructed T2-weighted template according to previous reports.11,13 Briefly, the RN was defined by six slices of the hyperintense circular region in the midbrain. The SNc was defined using six slices from superior to inferior, starting from the middle of the red nucleus, as a 4 × 10 mm kidney-shaped region between the RN and hypointense band. The SNr was defined as the hyperintense region lateral to the SNc and medial to the cerebral peduncle. Supplemental Figure 1 shows the location of these three structures. Step 2: an atlas-based segmentation pipeline (AutoSeg v3.0, University of North Carolina Neuro Image Analysis Laboratory) generated the segmentations in individual space based on the T2-weighted contrast. Step 3: automatic segmentation results from all subjects were inspected visually and corrected manually by a rater blinded to group information. In total, 17% of the automatic segmentation results were corrected manually (42 of 252 segmentations). Step 4: an affine registration algorithm was used to bring the ROIs in T2-weighted images to the quantitative MR images (R2* and QSM). Finally, means of R2* and QSM values from each ROI (including both sides of each structure) were calculated for individual subjects.

Thirty randomly-selected subjects at baseline were used to assess the inter-rater reliability of the manual correction step in our image segmentation approach. The agreement between two raters for six MRI measures was assessed by inter-class correlation coefficients (ICC) that were high for all measures (>0.91).

Statistical analyses

Demographic data were compared between groups at baseline using the Chi-square exact test for gender and the two-tailed Student's t-test for age and education years. Mixed effects models with a random intercept term were used for all longitudinal MRI measurements. The main variables of interest included Group (with PD as the reference group), Time (baseline or follow-up visit), and their interaction term (Time × Group, namely the PD-related longitudinal effect compared to controls). The covariates adjusted in the mixed effects models were baseline age, sex, and education years. For subgroup analyses, PD subgroups (based on disease duration) were compared to controls using mixed effects models with the same settings to assess potential stage-dependent longitudinal effects for R2* and QSM. In addition, the QSM measure was added as a covariate in the R2* mixed models to assess whether the longitudinal effects in R2* remained. Multiple comparisons were corrected using the Bonferroni procedure with a factor of 6 to account for 3 ROIs and 2 MRI measures (p<0.0083).

Finally, we explored the relationship between longitudinal changes (Δ) in R2* or QSM and changes in clinical measures using partial Pearson correlations with adjustment for age, sex, and LEDD. Residual scatter plots were used for visualizing the correlation results. Due to the explorative nature, we did not correct these analyses for multiple comparisons (p <0.05). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic information

At baseline, PD and controls were not significantly different in age, gender frequency, or education (Table 1). The drop-out rates for the 18-month visit were 11.1% for PD patients and 12.9% for controls. PD patients had significantly higher MDS-UPDRS-I, -II, and -III subscores, and higher HDRS and PDQ-39 scores at baseline. The MoCA score was similar for PD patients and controls.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical measures.

| Control | PD | Group* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of subjects | 62 | 72 | |

| Sex (males.females) | 33/29 | 35/37 | 0.608 |

| Age at baseline, yr (SD) | 66.2 (10.2) | 66.3 (9.5) | 0.936 |

| Education, yr (SD) | 15.7 (2.8) | 15.0 (3.2) | 0.226 |

| Disease duration (yr, SD) | - | 4.5 (4.5) | - |

| Hoehn and Yahr | - | 1.7 (0.7) | - |

| LEDD | - | 669 (464) | - |

| MDS-UPDRS part I | 2.9 (2.9) | 7.4 (4.8) | <0.0001 |

| MDS-UPDRS part II | 0.4 (1.5) | 7.4 (6.2) | <0.0001 |

| MDS-UPDRS part III | 3.2 (3.2) | 21.5 (14.7) | <0.0001 |

| MoCA | 25.6 (2.4) | 24.5 (3.7) | 0.450 |

| HDRS | 2.7 (2.6) | 5.0 (4.4) | <0.0001 |

| PDQ39 | 2.7 (2.7) | 11.5 (8.4) | <0.0001 |

Parenthetical terms are standard deviations (SD).

P value for sex is the group difference at baseline using the Chi-square test. The p values for age and education years are group differences at baseline using the two-tailed Student t test. P values for UPDRS-I, -II, -III, MoCA, HDRS, and PDQ39 are group difference at baseline using a mixed effects model adjusting for age, sex, and education years.

Abbreviations: HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; LEDD, levodopa equivalent daily dosage; MDS-UPDRS, the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, I = non-motor activities of daily living, II = motor activities of daily living, and III = motor evaluation by a trained rater; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PDQ-39, 39-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire; yr, years.

Bold and italic font indicates significance after Bonferroni correction.

Group analysis of midbrain R2* and QSM

At baseline, both R2* and QSM values in all PD patients were higher in both the SNc and SNr compared to controls (Table 2). Longitudinally, R2* increased faster in PD compared to controls in the SNc (time×group, p=0.002), whereas QSM did not (p=0.668). In the SNr, R2* and QSM in PD did not differ from controls (time×group, p≥0.084), although both decreased over time (time effect, p≤0.004). There were no significant differences in the RN for R2* or QSM, either for PD versus controls or over time.

Table 2. Midbrain region of interest analysis results for R2* and QSM measurements.

| Control | PD | P-values** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Group | Time | Group × Time | |

| R2* | |||||||

| SNc | 25.9 (0.4) | 26.0 (0.4) | 28.0 (0.4) | 30.2 (0.4) | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.002 |

| SNr | 37.3 (1.1) | 37.1 (1.1) | 41.5 (1.0) | 39.7 (1.0) | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.126 |

| RN | 35.5 (0.7) | 35.7 (0.8) | 37.0 (0.7) | 36.9 (0.7) | 0.092 | 0.770 | 0.838 |

| QSM | |||||||

| SNc | 44.8 (3.2) | 45.3 (3.4) | 64.2 (3.0) | 66.3 (3.3) | <0.0001 | 0.598 | 0.668 |

| SNr | 129.9 (5.1) | 119.1 (5.6) | 157.3 (4.7) | 133.1 (5.2) | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.084 |

| RN | 120.5 (5.6) | 123.6 (6.0) | 123.5 (5.3) | 123.4 (5.6) | 0.183 | 0.011 | 0.424 |

Values represent the mean and standard errors of the mean (SEM).

P values are from a mixed effects model adjusting for age, sex, and education years. The p value for Group is the group difference at baseline, the p value for Time is the change in the reference group (PD) over time, and the p value for Group × Time is the difference in changes between PD patients and controls. Bolded italic font indicates that p-values that are significant after Bonferroni correction (p < 0.0083).

Abbreviations: PD, Parkinson's disease; QSM, quantitative susceptibility mapping; RN, red nucleus; SNc, substantia nigra pars compacta; SNr, substantia nigra pars reticulata.

Subgroup analysis of midbrain R2* and QSM

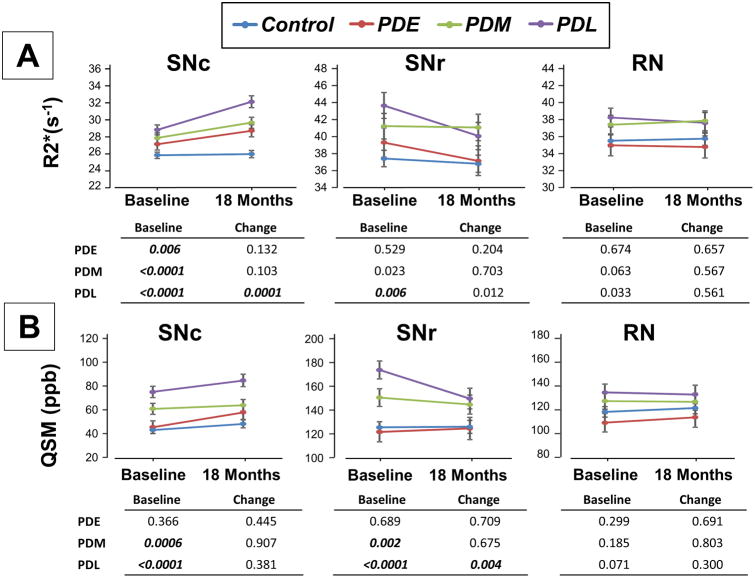

Baseline R2* in the SNc was higher in all PD subgroups (p≤0.006, Figure 1A) compared to controls. Longitudinally, only the PDL subgroup showed a strong time × subgroup interaction effect (p=0.0001), indicating a faster increase compared to controls. Baseline SNr R2* values were higher only in the PDL subgroup (Figure 1A) compared to controls (p=0.006). Longitudinally, there was a trend time × subgroup interaction (p=0.012) for the PDL subgroup, indicating a faster decease, but it did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni correction.

Figure 1.

Subgroup analysis of R2* (A) and QSM (B) in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), pars reticulata (SNr), and red nucleus (RN). PDE represents early stage PD patients (disease duration <1 year); PDM represents middle stage patients (<5 years); and PDL represents later stage patents (>5 years). Values in the tables are p values from mixed models that compared different PD subgroups to controls. Bolded and italicized text indicates significance after multiple comparison correction (p < 0.0083).

Baseline QSM metrics in the SNc and SNr were increased in both PDM (p≤0.002) and PDL (p<0.0001) patients (Figure 1B). There was no significant longitudinal effect for QSM at any disease stage in the SNc. Similar to R2*, QSM in the SNr showed a faster decrease in PDL patients compared to controls (p=0.004). No significant longitudinal R2* or QSM findings were observed in the RN.

Relationship between R2* and QSM

R2* and QSM were strongly correlated in all three structures (r=0.559, p<0.0001 for the SNc; r=0.867, p<0.0001 for the SNr; and r=0.812, p<0.0001 for the RN). To test whether the longitudinal effects of R2* could be modulated by QSM, we included QSM as a covariate for all R2* group and subgroup analyses above. Controlling for QSM did not affect the significance of either the group or time×group interaction effects for the R2* group analysis in the SNc (p=0.009 for group and p=0.0006 time×group interaction). In the subgroup analyses, the R2* time×subgroup effect for PDL patients persisted in the SNc (p<0.0001), but was abolished in the SNr (p=0.784), when QSM was controlled.

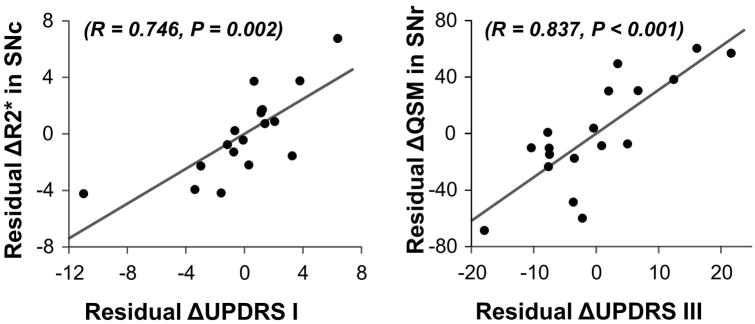

Correlation analyses with clinical measurements

Correlations between imaging and clinical measures were explored only where group and subgroup analyses demonstrated significant longitudinal effects (Supplementary Table 2) and the strongest correlations were plotted (Figure 2). As shown in Supplementary Table 2, ΔSNc R2* was correlated modestly with ΔUPDRS-I subscore in the overall PD group (r=0.337, p=0.016). Considering the PDL subgroup alone, ΔSNc R2* correlated with ΔUPDRS-I subscore (r=0.746, p=0.002) and less strongly with ΔUPDRS-II subscore (r=0.565, p=0.035) (Supplementary Table 2 and Figure 2), whereas ΔQSM in the SNr was correlated with ΔUPDRS-III subscore (r=0.837, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Correlation between ΔR2* and ΔUPDRS-I subscores over 18 months for later-stage PD patients (A), as well as ΔQSM and ΔUPDRS-III subscores (B). The scatter plots are residual values after regressing out age, sex, and LEDD.

Discussion

The current results support the hypothesis that susceptibility MRI may capture PD-related progression in the SN. More importantly, our study demonstrated for the first time a distinct pattern of PD progression in the SNc and SNr. Consistent with our initial hypothesis, R2*increased with PD progression in the SNc, the region of key PD pathology. When sub-grouped by disease duration, the analysis revealed that the longitudinal change was statistically significant only in later-stages of disease (>5 years) where it strongly correlated with non-motor progression. Intriguingly, we discovered significant R2* and QSM decreases in the SNr in later-stage PD patients that were correlated with motor progression. Together, these results suggest that susceptibility MRI can mark Parkinson's progression, and that R2* and QSM in the SNc and SNr may reflect different aspects of PD-related pathology and follow different patterns of progression. The findings also may resolve discrepant results from some prior longitudinal studies,15,17,18,32 and suggest that the pathophysiological processes of PD progression can be region-specific and non-monotonic.

Defining substantia nigra subregions

We investigated the SNc and SNr separately because cell death in PD occurs primarily in the SNc, but not in the SNr.1,21 Earlier, Ulla et al.32 defined the SNr and SNc by placing a circular ROI in the anterior and posterior regions of the SN, respectively, and demonstrated longitudinal R2* increases in both regions. Martin et al.11 identified the medial and lateral aspects of the SN as the SNc and SNr, respectively, and found significant cross-sectional R2* increases in the SNc, but not the SNr. Consistent with the latter study, our previous work identified the medial SN as having the most robust change in PD using a voxel-based approach.13 Thus, we utilized an anatomical definition for the SN similar to Martin et al.11 for the current study.

SNc R2* increases during PD progression and its practical implications

Our findings of greater rates of increases in SNc R2* in PD patients overall are in agreement with those reported by Ulla32 and Hopes et al.15 In a study of PD patients (N=19) early in their disease course (untreated at the beginning of the study), Wieler et al.17 did not observe longitudinal effects. Consistent with their finding, our subgroup analysis in early- to mid-stage PD patients also did not reach statistical significance.

Most studies, like Martin et al., have focused on early-stage PD patients in which neuroprotective therapies are thought to have the greatest impact.22,23 Many PD patients currently live >15 years after diagnosis,33 and their symptoms continue to progress throughout the disease course in the absence of disease-modifying therapy. Thus, it is imperative to find biomarkers that capture progression in later-stage PD. The current study provides the first evidence of an SNc R2* increase that is particularly clear in later-stage PD patients.

The finding that R2* in the SNc may be a later-stage PD biomarker is important because it suggests that there is ongoing PD pathological progression at the SNc even after the nigrostriatal tract has largely degenerated.22,23 SNc R2* progression was correlated strongly with non-motor symptoms that are the more prominent and disabling features in later disease stages. Previously, several groups have reported striatal changes that affect olfaction,34 working memory,35 and sleep.36 The current results add further evidence that pathological processes in the SNc are related to non-motor functions and their progression in later-stage patients.

SNc R2* may capture PD-related pathological processes beyond iron

The R2* contrast consists of both susceptibility and the transverse relaxation rate that may be influenced by local myelin and cellular structural properties,37,38 whereas QSM captures more iron-specific susceptibility changes.9,38 Previous studies supported that QSM may be a better marker than R2*for iron in brain tissue.8,9 We found QSM is higher in the SN only in middle- and later-stage patients, consistent with reports that increased iron is observed in advanced-stage PD patients.4,5,39 Our study, however, did not detect significant longitudinal changes in QSM, possibly because QSM is less stable than R2*40 despite having a better signal for iron.9 The fact that R2* changes in the SNc persisted even after adjusting for QSM suggests that R2* may capture, besides iron, the complex microstructural changes occurring during PD progression. Consistent with this, our companion study 10 demonstrated that R2* also may reflect α-synuclein and possibly neuronal cell loss in the SN.

Non-linear SNr changes during PD progression

Previous susceptibility MRI studies in the SNr have been inconsistent. Two studies observed higher R2* values in the SNr of PD patients,12,32 whereas one did not.11 Consistent with the former studies, our study found higher R2* in the SNr at baseline. Because adjusting for QSM abolishes SNr R2* changes, the SNr R2* finding likely is dominated by iron changes in this structure. A postmortem study suggests no neuronal loss in the SNr of PD patients.21 Thus, SNr iron changes may be a secondary or compensatory process relative to the primary PD pathology in the SNc. It is not surprising then that SNr R2* and QSM seemed to have different patterns of change compared to the SNc.

Ulla et al.32 found that R2* in the SNr increased over a 36 months epoch. Contrary to this, we did not detect significant PD longitudinal changes compared to controls in our group analyses. The different SNr definition and longer time period used by Ulla et al.32 may contribute to disparate results of the two studies. In our subgroup analyses (the first study of its type), we found significant decreases in R2* and QSM in the SNr in later-stage PD patients that suggests there may be an inflection point for iron accumulation in the SNr during PD progression. The timing of this point (ca. 5 y after diagnosis), corresponds to the end of the “honeymoon period” in PD.26 Interestingly, decreasing SNr R2* and QSM correlated strongly with less PD motor deterioration in PD patients with disease duration >5 years. Thus, this shift in SNr R2* may reflect a change in the brain compensatory processes relating (or responding) to motor disability.

The current study demonstrated an intriguing shift in the SNr from higher iron status at the beginning of PD to a dynamic decrease as disease advances. Postmortem studies of PD patients generally involve those at more advanced disease stages, and thus may not capture this non-linear pattern of iron accumulation in the SNr. Our finding underscores the importance of using iron-sensitive MRI sequences to delineate the time-course of in vivo iron changes in a stage- and region-specific manner. This may provide a better understanding regarding the role of iron in the pathophysiology of PD progression, as well as an excellent biomarker for therapies that engage iron.

Together, these data suggested dynamical, shifting roles of iron in PD progression. In the early part of the PD process, iron accumulation in the SNr may play a compensatory role to “absorb” the consequences of active neurodegenerative processes occurring in the SNc, whereas with disease progression, iron accumulated in the SNr may be mobilized and redistributed. Indeed, the faster loss of iron from the SNr seems to occur in later-stage PD patients, and is related to slower UPDRS-III progression. Because of the hypothesis that iron may play an etiological role in PD, there are ongoing efforts towards using iron chelating agents41 to modify disease progression.42 If iron accumulation indeed provides compensation in early-stage PD patients, this effort might be counter-productive. Our data suggested that facilitating iron mobilization out of the SNr, however, might be beneficial in later-stage patients and chelating the redistributed iron may thus be something to consider. As such, clinical trials may be improved by monitoring a combination of R2* in the SNc and QSM in the SNr.

Limitations

There are several limitations for our study. First, there is a lack of robust measures for clinical progression. Although the UPDRS-III is a standard tool used to assess PD motor deficits, it is an insensitive longitudinal marker for PD progression43 because ongoing symptomatic treatments are targeted to diminish those changes. In addition, UPDRS-III is subjective, has low inter-rater reliability,44 and motor symptoms can vary depending on the time of day, subject activity level, and/or mood among other factors. We intended to minimize this by using UPDRS-II data to capture motor-related symptoms experienced in the previous week, by completing the UPDRS-III exams at approximately the same time for each subject (morning), and by standardizing study visit protocols. Promisingly, we did find a strong correlation between ΔQSM in the SNr and ΔUPDRS-III, and a moderate correlation between SNc ΔR2* and UPDRS-II, in later stage PD patients, that coincides with the onset of decreasing SNr values. Second, our MRI and clinical data were captured in the on-drug state and thus R2* and QSM measures may be confounded by PD medications. R2* and QSM studies in drug naïve PD patients and its progression may help address this issue, but it is both difficult and impractical to determine the medication effect in later-stage PD patients. In particular, medication has a substantial impact on UPDRS-III scores that make it less sensitive to the actual severity of disease in patients. The measured UPDRS-III scores more likely reflect symptoms that are less responsive to levodopa treatment. This may account for the lack of a correlation between SNc R2* values and UPDRS-III scores. Future studies to investigate the effects of PD medications on susceptibility MRI are warranted.

Conclusion

Different neuroimaging modalities have been studied in recent decades with the goal of detecting PD-related pathological changes. The current study, coupled with our companion report10, offers new perspectives that are important to integrate into prior findings. Specifically, dopamine deficits (PET and SPECT)25 and volume loss (morphometric MRI) in the striatum29 are most pronounced in early-stage PD patients and “plateau” after five years. Conversely, extra-nigral changes (such as cortical volume and gyrification) persist to later disease stages. The current study, by following susceptibility MRI changes longitudinally in PD patients at different disease stages, demonstrated a longitudinal increase in SNc R2*, the location of primary neuronal cell loss in the SN. Most intriguingly, our data suggested a non-linear pattern of R2* and QSM changes in the SNr of PD patients. Our findings, in concert with previous neuroimaging studies, offer a picture that integrates stage-, location-, biological-dependencies of different neuroimaging measures, and provides a strawman for possibly reconciling apparently contradictory findings in biomarker research, as well as helping to understand the pathophysiology of PD progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express gratitude to all of the participants who volunteered for this study and study personnel who contributed to its success. This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (NS060722 to XH) and Parkinson's Disease Biomarker Program (NS082151 to XH), the Hershey Medical Center General Clinical Research Center (National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR033184 that is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant UL1 TR000127), and the PA Department of Health Tobacco CURE Funds. All analyses, interpretations, and conclusions are those of the authors and not the research sponsors.

Study funding: National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (NS060722 and NS082151 to XH), the Hershey Medical Center General Clinical Research Center (National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR033184 that is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant UL1 TR000127), and the PA Department of Health Tobacco CURE Funds.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: the authors have no financial disclosures/conflicts to report.

- Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution;

- Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique;

- Manuscript: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique;

Guangwei Du: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A.

Mechelle Lewis: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B.

Christopher Sica: 1C, 3B.

Lu He: 1C, 2B

James R Connor: 1A, 3B

Lan Kong: 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B.

Richard Mailman: 1A, 3B.

Xuemei Huang: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B.

References

- 1.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kordower JH, Olanow CW, Dodiya HB, et al. Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 8):2419–2431. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sofic E, Riederer P, Heinsen H, et al. Increased iron (III) and total iron content in post mortem substantia nigra of parkinsonian brain. J Neural Transm. 1988;74(3):199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF01244786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dexter DT, Wells FR, Lees AJ, et al. Increased nigral iron content and alterations in other metal ions occurring in brain in Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 1989;52(6):1830–1836. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch EC, Brandel JP, Galle P, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y. Iron and aluminum increase in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease: an X-ray microanalysis. J Neurochem. 1991;56(2):446–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galazka-Friedman J, Bauminger ER, Friedman A, Barcikowska M, Hechel D, Nowik I. Iron in parkinsonian and control substantia nigra--a Mossbauer spectroscopy study. Mov Disord. 1996;11(1):8–16. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman A, Bauminger ER, Galazka-Friedman J, et al. Is iron involved in pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease--Mossbauer spectroscopy study of substantia nigra in control and disease brains. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 1996;30(Suppl 2):95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh AJ, Wilman AH. Susceptibility phase imaging with comparison to R2 mapping of iron-rich deep grey matter. Neuroimage. 2011;57(2):452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Liu T. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM): Decoding MRI data for a tissue magnetic biomarker. Magn Reson Med. 2014;73(1):82–101. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis MM, Du G, Baccon J, et al. Susceptibility MRI captures nigral pathology in patients with parkinsonian syndromes. Mov Disord. 2018;XX(XX):XXX–XXX. doi: 10.1002/mds.27381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin WR, Wieler M, Gee M. Midbrain iron content in early Parkinson disease: a potential biomarker of disease status. Neurology. 2008;70(16 Pt 2):1411–1417. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000286384.31050.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du G, Lewis MM, Sen S, et al. Imaging nigral pathology and clinical progression in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27(13):1636–1643. doi: 10.1002/mds.25182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du G, Liu T, Lewis MM, et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping of the midbrain in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31(3):317–324. doi: 10.1002/mds.26417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peran P, Cherubini A, Assogna F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging markers of Parkinson's disease nigrostriatal signature. Brain. 2010;133(11):3423–3433. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopes L, Grolez G, Moreau C, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Features of the Nigrostriatal System: Biomarkers of Parkinson's Disease Stages? PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0147947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulla M, Bonny JM, Ouchchane L, Rieu I, Claise B, Durif F. Is R2* a new MRI biomarker for the progression of Parkinson's disease? A longitudinal follow-up. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wieler M, Gee M, Martin WR. Longitudinal midbrain changes in early Parkinson's disease: iron content estimated from R2*/MRI. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(3):179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi ME, Ruottinen H, Saunamaki T, Elovaara I, Dastidar P. Imaging brain iron and diffusion patterns: a follow-up study of Parkinson's disease in the initial stages. Acad Radiol. 2014;21(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehericy S, Vaillancourt DE, Seppi K, et al. The role of high-field magnetic resonance imaging in parkinsonian disorders: Pushing the boundaries forward. Mov Disord. 2017;32(4):510–525. doi: 10.1002/mds.26968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuite P. Magnetic resonance imaging as a potential biomarker for Parkinson's disease. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2016;175:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardman CD, McRitchie DA, Halliday GM, Cartwright HR, Morris JG. Substantia nigra pars reticulata neurons in Parkinson's disease. Neurodegeneration. 1996;5(1):49–55. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrish PK, Sawle GV, Brooks DJ. The rate of progression of Parkinson's disease. A longitudinal [18F]DOPA PET study. Adv Neurol. 1996;69:427–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nurmi E, Ruottinen HM, Bergman J, et al. Rate of progression in Parkinson's disease: a 6-[18F]fluoro-L-dopa PET study. Mov Disord. 2001;16(4):608–615. doi: 10.1002/mds.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarz J, Storch A, Koch W, Pogarell O, Radau PE, Tatsch K. Loss of dopamine transporter binding in Parkinson's disease follows a single exponential rather than linear decline. J Nucl Med. 2004;45(10):1694–1697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perlmutter JS, Norris SA. Neuroimaging biomarkers for Parkinson disease: facts and fantasy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(6):769–783. doi: 10.1002/ana.24291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rascol O, Payoux P, Ory F, Ferreira JJ, Brefel-Courbon C, Montastruc JL. Limitations of current Parkinson's disease therapy. Ann Neurol. 2003;53(Suppl 3):S3–12. doi: 10.1002/ana.10513. discussion S12-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burciu RG, Ofori E, Archer DB, et al. Progression marker of Parkinson's disease: a 4-year multi-site imaging study. Brain. 2017;140(8):2183–2192. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(3):181–184. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis MM, Du G, Lee EY, et al. The pattern of gray matter atrophy in Parkinson's disease differs in cortical and subcortical regions. J Neurol. 2016;263(1):68–75. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7929-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu R, Guo X, Park Y, et al. Caffeine intake, smoking, and risk of Parkinson disease in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(11):1200–1207. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2033–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulla M, Bonny JM, Ouchchane L, Rieu I, Claise B, Durif F. Is R2* a New MRI Biomarker for the Progression of Parkinson's Disease? A Longitudinal Follow-Up. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cilia R, Cereda E, Klersy C, et al. Parkinson's disease beyond 20 years. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(8):849–855. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siderowf A, Newberg A, Chou KL, et al. [99mTc]TRODAT-1 SPECT imaging correlates with odor identification in early Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;64(10):1716–1720. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000161874.52302.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis SJ, Dove A, Robbins TW, Barker RA, Owen AM. Cognitive impairments in early Parkinson's disease are accompanied by reductions in activity in frontostriatal neural circuitry. J Neurosci. 2003;23(15):6351–6356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06351.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iranzo A, Lomena F, Stockner H, et al. Decreased striatal dopamine transporter uptake and substantia nigra hyperechogenicity as risk markers of synucleinopathy in patients with idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder: a prospective study [corrected] Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1070–1077. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duyn JH, Schenck J. Contributions to magnetic susceptibility of brain tissue. NMR Biomed. 2017;30(4) doi: 10.1002/nbm.3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haacke EM, Cheng NY, House MJ, et al. Imaging iron stores in the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;23(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gotz ME, Double K, Gerlach M, Youdim MB, Riederer P. The relevance of iron in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1012:193–208. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang R, Xie G, Zhai M, et al. Stability of R2* and quantitative susceptibility mapping of the brain tissue in a large scale multi-center study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45261. doi: 10.1038/srep45261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devos D, Moreau C, Devedjian JC, et al. Targeting chelatable iron as a therapeutic modality in Parkinson's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(2):195–210. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grolez G, Moreau C, Sablonniere B, et al. Ceruloplasmin activity and iron chelation treatment of patients with Parkinson's disease. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:74. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0331-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ofori E, Pasternak O, Planetta PJ, et al. Longitudinal changes in free-water within the substantia nigra of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2015 doi: 10.1093/brain/awv136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer JL, Coats MA, Roe CM, Hanko SM, Xiong C, Morris JC. Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale-Motor Exam: inter-rater reliability of advanced practice nurse and neurologist assessments. Journal of advanced nursing. 2010;66(6):1382–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.