Abstract

Study Design

Randomized trial with a concurrent observational cohort study

Objective

To compare eight-year outcomes between surgery and nonoperative care and among different fusion techniques for symptomatic lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS).

Summary of Background Data

Surgical treatment of DS has been shown to be more effective than nonoperative treatment out to four years. This study sought to further determine the long-term (8-year) outcomes.

Methods

Surgical candidates with DS from thirteen centers with at least twelve weeks of symptoms and confirmatory imaging were offered enrollment in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational cohort study (OBS). Treatment consisted of standard decompressive laminectomy (with or without fusion) versus standard nonoperative care. Primary outcome measures were the Short Form-36 (SF-36) bodily pain and physical function scores and the modified Oswestry Disability Index at six weeks, three months, six months and yearly up to eight years.

Results

Data were obtained for 69% of the randomized cohort and 57% of the observational cohort at the eight-year follow up. Intent-to-treat analyses of the randomized group were limited by high levels of nonadherence to the randomized treatment. As-treated analyses in the randomized and observational groups showed significantly greater improvement in the surgery group on all primary outcome measures at all time points through eight years. Outcomes were similar among patients treated with uninstrumented posterolateral fusion, instrumented posterolateral fusion, and 360° fusion.

Conclusion

For patients with symptomatic DS, patients who received surgery had significantly greater improvements in pain and function compared to nonoperative treatment through eight years of follow-up. Fusion technique did not affect outcomes.

Keywords: spinal stenosis, degenerative spondylolisthesis, randomized trial, surgery, nonoperative, SPORT, outcomes

Introduction

Degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS) with lumbar stenosis is commonly treated with lumbar decompression and fusion.1 Prior studies have compared outcomes of surgical or nonoperative treatment for spinal stenosis but included mixed groups of patients with and without DS2–5 or were limited by small sample sizes and a lack of validated outcome measures.6–9

SPORT demonstrated that DS patients treated surgically had significantly greater improvements in pain and function compared to those treated nonoperatively through four years of follow-up.9 However, several studies have found that the early advantage of surgery compared to nonoperative treatment narrowed over time.2–12 In this study, we sought to compare surgical and nonoperative outcomes out to eight years for DS patients and also to compare results among different fusion techniques.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

SPORT was conducted at thirteen US medical centers with multidisciplinary spine practices across eleven states. The study included a randomized trial and an observational cohort of patients who declined randomization.13

Patient Population

The population has been described in detail previously.9,14 Briefly, all patients had neurogenic claudication or radicular leg symptoms for at least 12 weeks, cross-sectional imaging demonstrating spinal stenosis, DS on a standing lateral radiograph, and physician confirmation that they were surgical candidates. Patients with adjacent levels of stenosis were eligible, while patients with spondylolysis and isthmic spondylolisthesis were not. Enrollment took place from March 2000 to February 2005.

Study Interventions

The protocol surgery consisted of a standard, posterior decompressive laminectomy with or without fusion using autogenous iliac crest bone-graft. The use of pedicle screw instrumentation or interbody fusion was at the discretion of the treating surgeon.13 Fusion surgeries were classified into the following groups: 1) decompression with posterolateral in situ fusion (PLF); 2) decompression with instrumented posterolateral fusion with pedicle screws (PPS); and 3) decompression with interbody fusion plus instrumented posterolateral fusion with pedicle screws (360°). The nonoperative protocol was individualized by the treating physician, but included, at a minimum, physical therapy, education and counseling with instructions for exercising at home, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents if tolerated by the patients.13,15

Outcome Measures

The primary end points were the Short Form-36 (SF-36) bodily pain and physical function scores16–19 and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons/Modems version)20 measured at six weeks, three months, six months and yearly out to eight years. Secondary outcomes included patient self-assessed global improvement, satisfaction with current symptoms and care,21 the Stenosis Bothersomeness Index,2,22 Low Back Pain Bothersomeness,2 and Leg Pain Bothersomeness.2

SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating more severe symptoms; the ODI ranges from 0–100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms; the Stenosis Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms. Low Back Pain and Leg Pain Bothersomeness ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms. Surgical treatment effect was defined as the mean changes from baseline in the surgical group minus that in the nonoperative group (difference-in-difference).

Statistical Methods

The statistical methods for the analysis of this trial have been reported in detail in previous publications.1,9,12,14,23 Data from the randomized trial was initially analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis. Due to crossover, subsequent analyses were based on treatments actually received, as described previously.11,23

Follow-up times were measured from enrollment for the intent-to-treat analyses and from the beginning of treatment for the as-treated analyses (i.e., the time of surgery for the surgical group and the time of enrollment for the nonoperative group). All changes from baseline before surgery were included in the estimates of the nonoperative treatment effect and all changes after surgery were included in the estimates of the surgical effect.

Repeated measures of outcomes were used as the dependent variables. The treatment received was included as a time-varying covariate. To evaluate the two treatment arms across all time periods, a global significance test was based on the time-weighted average of the outcomes (area under the curve) and compared using a Wald test.24 Kaplan-Meier estimates of reoperation rates at eight years were computed for the observational and randomized cohorts and compared via the log-rank test.

Comparisons among fusion groups were done in a hierarchical fashion and are described in detail in previous publications.9,14 At each assessment interval, the first step was to test for any differences among the three fusion groups. If a difference was detected at p < 0.10, the next step evaluated differences between the three groups based on pair-wise comparisons. For these comparisons Type I error was set at 0.05. Since these comparisons represent the most basic approach for evaluating for treatment differences they were considered planned comparisons and, as such, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

To adjust for potential confounding, baseline variables associated with missing data or treatment received were included as adjusting covariates in longitudinal regression models.24 Computations were performed using SAS software (PROC MIXED for continuous data with normal random effects and PROC GENMOD for binary and non-normal secondary outcomes; SAS software, version 9.1).

Results

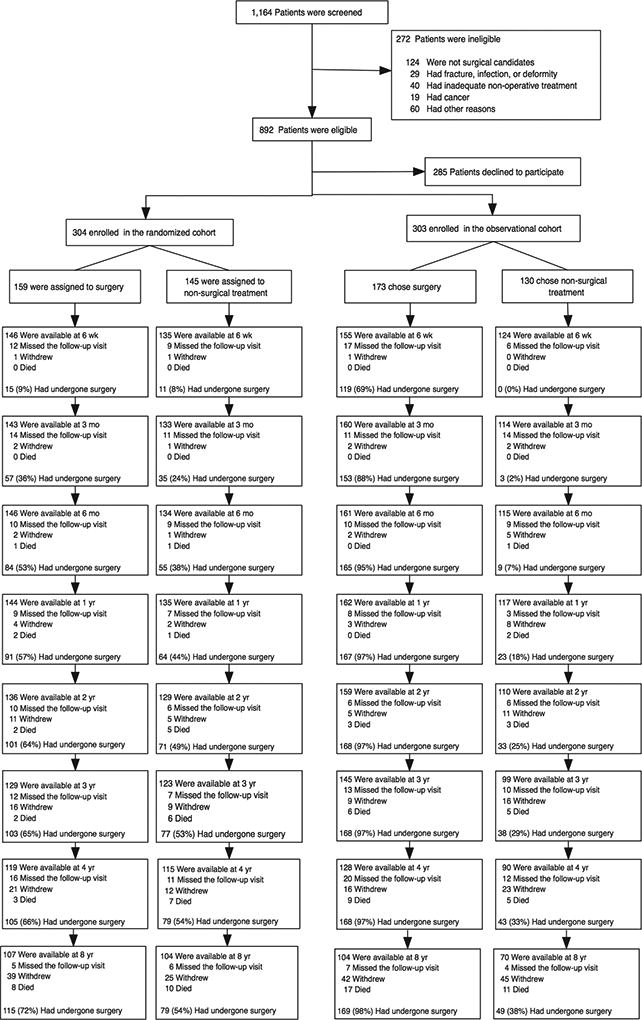

A total of 607 participants out of 892 eligible participants (304 in the randomized trial and 303 in the observational cohort) with DS were enrolled. In the randomized cohort, 159 patients were assigned to surgery, and 145 patients were assigned to nonoperative treatment. Of those 159 assigned to the surgical cohort, 64% (101) underwent surgery by two years, 66% (105) by four years, and 72% (115) by eight years. Of those 145 assigned to nonoperative care, 49% (71) underwent surgery by two years and 54% (79) by four years, but no additional patients underwent surgery between four and eight years (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Exclusion, Enrollment, Randomization and Follow-up of Trial Participants. The values for surgery, withdrawal, and death are cumulative over eight years. For example, a total of 8 patients died during the follow-up period. [Data set 09/03/13]

Of the 303 patients enrolled in the observational cohort, 173 initially chose surgical treatment, and 130 chose nonoperative treatment. In the surgery group, 97% (168) underwent surgery by two years, and one additional patient underwent surgery between four and eight years. Of those 130 patients in the observational cohort initially in the nonoperative group, 25% (33) underwent surgery by two years and 38% (49) underwent surgery by eight years.

A total of 601 patients out of 607 enrolled (99%) had at least one follow-up visit and were included in the analysis. In the combined cohort, 412 of 607 (68%) patients had undergone surgery by eight years, with 84% of these (345) being within the first year (Figure 1).

Patient Characteristics

In the combined as-treated cohort, the surgery patients were younger and more likely to be receiving compensation (Table 1). The surgery group also reported SF-36 BP (31.6 vs 36.9, P = 0.001) and PF (32 vs 39.3, P <0.001), ODI (43.9 vs 36.5, P<0.001), stenosis bothersomeness (15.3 vs 13.3, P <0.001), and leg pain bothersomeness (4.6 vs 4.3, p = 0.05) scores indicative of significantly more severe baseline symptoms compared to the nonoperative group.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures according to diagnosis and treatment received*

| Surgery (n=409) |

Non- Operative (n=192) |

p-value |

PLF (n=84) |

PPS (n=222) |

360° (n=70) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 64.6 (10.1) | 69 (10.2) | <0.001 | 67.3 (9.9) | 64.8 (9.4) | 60.2 (10.3) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Female - no. (%) | 278 (68%) | 134 (70%) | 0.72 | 53 (63%) | 147 (66%) | 56 (80%) | 0.053 |

|

| |||||||

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic - no. (%)† | 400 (98%) | 187 (97%) | 0.99 | 84 (100%) | 213 (96%) | 70 (100%) | 0.041 |

|

| |||||||

| Race - White - no. (%) | 352 (86%) | 154 (80%) | 0.086 | 80 (95%) | 183 (82%) | 61 (87%) | 0.015 |

|

| |||||||

| Education - At least some college - no. (%) | 278 (68%) | 122 (64%) | 0.33 | 54 (64%) | 157 (71%) | 40 (57%) | 0.095 |

|

| |||||||

| Marital Status - Married - no. (%) | 277 (68%) | 119 (62%) | 0.2 | 59 (70%) | 150 (68%) | 45 (64%) | 0.73 |

|

| |||||||

| Work Status - no. (%) | 0.81 | 0.022 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Full or part time | 151 (37%) | 67 (35%) | 31 (37%) | 72 (32%) | 38 (54%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Disabled | 37 (9%) | 14 (7%) | 7 (8%) | 23 (10%) | 5 (7%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Retired | 171 (42%) | 86 (45%) | 40 (48%) | 94 (42%) | 19 (27%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Other | 50 (12%) | 25 (13%) | 6 (7%) | 33 (15%) | 8 (11%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Compensation - Any - no. (%)‡ | 36 (9%) | 5 (3%) | 0.008 | 5 (6%) | 23 (10%) | 6 (9%) | 0.48 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD)§ | 29.3 (6.4) | 28.8 (5.8) | 0.37 | 30.2 (8.6) | 29.2 (5.4) | 29.7 (6.4) | 0.44 |

|

| |||||||

| Smoker - no. (%) | 35 (9%) | 16 (8%) | 0.95 | 6 (7%) | 19 (9%) | 8 (11%) | 0.64 |

|

| |||||||

| Comorbidities - no. (%) | |||||||

| Diabetes | 53 (13%) | 27 (14%) | 0.81 | 10 (12%) | 33 (15%) | 6 (9%) | 0.37 |

|

| |||||||

| Osteoporosis | 45 (11%) | 24 (12%) | 0.69 | 12 (14%) | 28 (13%) | 2 (3%) | 0.046 |

|

| |||||||

| Heart Problem | 75 (18%) | 47 (24%) | 0.1 | 19 (23%) | 37 (17%) | 14 (20%) | 0.46 |

|

| |||||||

| Depression | 73 (18%) | 25 (13%) | 0.17 | 22 (26%) | 35 (16%) | 9 (13%) | 0.053 |

|

| |||||||

| Joint Problem | 230 (56%) | 114 (59%) | 0.52 | 42 (50%) | 129 (58%) | 41 (59%) | 0.41 |

| Pseudoclaudication - Any - no. (%) | 352 (86%) | 159 (83%) | 0.36 | 77 (92%) | 187 (84%) | 58 (83%) | 0.19 |

| Pain radiation - any | 319 (78%) | 149 (78%) | 1 | 69 (82%) | 170 (77%) | 52 (74%) | 0.46 |

|

| |||||||

| Any Neurological Deficit | 219 (54%) | 108 (56%) | 0.59 | 55 (65%) | 108 (49%) | 37 (53%) | 0.031 |

|

| |||||||

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 107 (26%) | 43 (22%) | 0.37 | 38 (45%) | 41 (18%) | 20 (29%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 115 (28%) | 54 (28%) | 0.92 | 31 (37%) | 51 (23%) | 21 (30%) | 0.044 |

|

| |||||||

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 95 (23%) | 51 (27%) | 0.43 | 23 (27%) | 52 (23%) | 11 (16%) | 0.22 |

|

| |||||||

| Listhesis Level | 0.42 | 0.58 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| L3–L4 | 42 (10%) | 15 (8%) | 10 (12%) | 18 (8%) | 6 (9%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| L4–L5 | 367 (90%) | 177 (92%) | 74 (88%) | 204 (92%) | 64 (91%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Stenotic Levels (Mod/Severe) | 0.54 | <0.001 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| None | 13 (3%) | 10 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (2%) | 6 (9%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| One | 256 (63%) | 114 (59%) | 47 (56%) | 141 (64%) | 53 (76%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Two | 114 (28%) | 58 (30%) | 29 (35%) | 64 (29%) | 10 (14%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Three+ | 26 (6%) | 10 (5%) | 8 (10%) | 12 (5%) | 1 (1%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Stenosis Locations | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Central | 376 (92%) | 173 (90%) | 0.56 | 84 (100%) | 206 (93%) | 59 (84%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Lateral Recess | 375 (92%) | 171 (89%) | 0.37 | 75 (89%) | 203 (91%) | 66 (94%) | 0.54 |

|

| |||||||

| Neuroforamen | 169 (41%) | 74 (39%) | 0.58 | 32 (38%) | 91 (41%) | 38 (54%) | 0.089 |

|

| |||||||

| Stenosis Severity | 0.44 | 0.009 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Mild | 13 (3%) | 10 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (2%) | 6 (9%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Moderate | 145 (35%) | 70 (36%) | 32 (38%) | 71 (32%) | 28 (40%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Severe | 251 (61%) | 112 (58%) | 52 (62%) | 146 (66%) | 36 (51%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Instability‖ | 37 (9%) | 10 (5%) | 0.14 | 3 (4%) | 27 (12%) | 4 (6%) | 0.036 |

|

| |||||||

| HRQOL Scales¶ | |||||||

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score (SD) | 31.6 (18.9) | 36.9 (19.3) | 0.001 | 33.7 (18) | 30.6 (19.1) | 32.1 (19.3) | 0.43 |

|

| |||||||

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score (SD) | 32 (21.5) | 39.3 (23.5) | <0.001 | 31.9 (17.4) | 31.2 (22.4) | 33.7 (22) | 0.68 |

| Oswestry (ODI) (SD)** | 43.9 (16.9) | 36.5 (18.8) | <0.001 | 41.4 (15.6) | 45 (17) | 44.3 (17.2) | 0.24 |

|

| |||||||

| Stenosis Frequency Index (0–24) (SD)†† | 14.6 (5.5) | 12.6 (5.6) | <0.001 | 14.5 (5.4) | 15 (5.6) | 13.6 (5.7) | 0.2 |

|

| |||||||

| Stenosis Bothersome Index (0–24) (SD)‡‡ | 15.3 (5.5) | 13.3 (5.4) | <0.001 | 15.6 (5.2) | 15.7 (5.7) | 14.3 (5.7) | 0.19 |

|

| |||||||

| Back Pain Bothersomeness (SD)§§ | 4.4 (1.8) | 4.1 (1.8) | 0.081 | 4.5 (1.8) | 4.4 (1.8) | 4.3 (1.7) | 0.72 |

| Leg Pain Bothersomeness (SD)¶¶ | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.3 (1.7) | 0.05 | XX | XX | XX | XX |

Patients in the two cohorts (randomized and observational) combined were classified according to whether they received surgical treatment or only nonsurgical treatment during the first 8 years of enrollment. In total, 84 patients received PLF surgery, 222 patients received PPS surgery, and 71 patients received 360° surgery within 8-year from enrollment (see table 2). One 360° patient did not have follow-up through 8 years, leaving 84 PLF, 222 PPS, and 70 360° patients in the current analysis.

Race or ethnic group was self-assessed. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

This category includes patients who were receiving or had applications pending for workers compensation, Social Security compensation, or other compensation.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Spinal instability is defined as a change of more than 10 degrees of angulation or more than 4 mm of translation of the vertebrae between flexion and extension of the spine.

- The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms

- The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

- The Stenosis Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

- The Stenosis Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

- The Low Back Pain Bothersomness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Low Back Pain Bothersomness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Leg Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

At eight years, 264 of 601 patients were lost to follow-up, with 337 (56%) of the original enrollees remaining in the study. Table 2 compares the baseline characteristics of those who remained in the study with those who dropped out of the study. Patients retained in the study were younger, had more formal education, and were more likely to be employed and/or receiving compensation (Workman’s Compensation or Social Security Benefits) at baseline. These same patients were less likely to have diabetes or heart problems. With respect to 2-year outcomes, patients in the surgical group who were subsequently lost to follow-up had significantly worse outcomes except on the ODI, while the results for those in the nonoperative group subsequently lost to follow-up were similar to those retained in the study. As a result, the surgical treatment effect at 2 years was greater among those retained in the study; this difference was statistically significant for BP and stenosis bothersomeness (Table 3).

Table 2.

Additional. Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures according to patient follow-up status as of 09/03/2013 when the DS 8yr data were pulled.

| Patients currently in study (n=337) |

Patients lost to follow-up (n=264) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 63.6 (9.4) | 69.2 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Female - no. (%) | 234 (69%) | 178 (67%) | 0.66 |

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic - no. (%)† | 330 (98%) | 257 (97%) | 0.85 |

| Race - White - no. (%) | 293 (87%) | 213 (81%) | 0.048 |

| Education - At least some college - no. (%) | 238 (71%) | 162 (61%) | 0.021 |

| Marital Status - Married - no. (%) | 230 (68%) | 166 (63%) | 0.2 |

| Work Status - no. (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Full or part time | 145 (43%) | 73 (28%) | |

| Disabled | 31 (9%) | 20 (8%) | |

| Retired | 121 (36%) | 136 (52%) | |

| Other | 40 (12%) | 35 (13%) | |

| Compensation - Any - no. (%)‡ | 31 (9%) | 10 (4%) | 0.014 |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD)§ | 29.2 (5.7) | 29.2 (6.8) | 1 |

| Smoker - no. (%) | 26 (8%) | 25 (9%) | 0.54 |

| Comorbidities - no. (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 36 (11%) | 44 (17%) | 0.043 |

| Osteoporosis | 40 (12%) | 29 (11%) | 0.83 |

| Heart Problem | 54 (16%) | 68 (26%) | 0.004 |

| Depression | 58 (17%) | 40 (15%) | 0.57 |

| Joint Problem | 185 (55%) | 159 (60%) | 0.22 |

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score (SD)‖ | 34.5 (19.7) | 31.7 (18.3) | 0.075 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score (SD) | 35.9 (21.8) | 32.3 (23) | 0.054 |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score (SD) | 50.2 (11.5) | 50 (11.6) | 0.78 |

| Oswestry (ODI) (SD)** | 42.1 (17.8) | 40.9 (17.9) | 0.43 |

| Stenosis Frequency Index (0–24) (SD)†† | 13.9 (5.3) | 14.1 (5.9) | 0.65 |

| Stenosis Bothersome Index (0–24) (SD)‡‡ | 14.7 (5.4) | 14.6 (5.8) | 0.81 |

| Back Pain Bothersomeness (SD)§§ | 4.3 (1.8) | 4.2 (1.8) | 0.81 |

| Leg Pain Bothersomeness (SD)¶¶ | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.5 (1.7) | 0.91 |

| Pseudoclaudication - Any - no. (%) | 289 (86%) | 222 (84%) | 0.65 |

| Dermatomal pain radiation - no. (%) | 261 (77%) | 207 (78%) | 0.86 |

| Any Neurological Deficit - no. (%) | 178 (53%) | 149 (56%) | 0.42 |

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 86 (26%) | 64 (24%) | 0.79 |

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 96 (28%) | 73 (28%) | 0.89 |

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 75 (22%) | 71 (27%) | 0.22 |

| No. moderate or severe stenotic levels - no. (%) | 0.088 | ||

| None | 16 (5%) | 7 (3%) | |

| One | 218 (65%) | 152 (58%) | |

| Two | 85 (25%) | 87 (33%) | |

| Three+ | 18 (5%) | 18 (7%) | |

| Stenosis Locations - no. (%) | |||

| Central | 303 (90%) | 246 (93%) | 0.2 |

| Lateral Recess | 313 (93%) | 233 (88%) | 0.071 |

| Neuroforamen | 151 (45%) | 92 (35%) | 0.017 |

| Stenosis Severity - no. (%) | 0.21 | ||

| Mild | 16 (5%) | 7 (3%) | |

| Moderate | 126 (37%) | 89 (34%) | |

| Severe | 195 (58%) | 168 (64%) | |

| Instability - no. (%)******* | 29 (9%) | 18 (7%) | 0.51 |

| HRQOL Scales ****** | |||

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score (SD)‖ | 34.5 (19.7) | 31.7 (18.3) | 0.075 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score (SD) | 35.9 (21.8) | 32.3 (23) | 0.054 |

| Oswestry (ODI) (SD)** | 42.1 (17.8) | 40.9 (17.9) | 0.43 |

Table 3.

Time-weighted average of treatment effects at 2 years (AUC) from adjusted* as-treated randomized and observational cohorts combined primary outcome analysis, according to treatment received and patient follow-up status.

| DS | Patient follow-up status | Surgical | Non- operative |

Treatment Effect† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) (SE)†† | Currently in study | 30.8 (1) | 13.1 (1.2) | 17.7 (15.1, 20.3) |

| Lost to follow-up | 25.1 (1.3) | 14.1 (1.4) | 11.1 (7.8, 14.4) | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.60 | 0.002 | |

|

| ||||

| SF-36 Physical Function (PF) (SE)†† | Currently in study | 24.8 (1) | 10.4 (1.2) | 14.4 (11.9, 16.9) |

| Lost to follow-up | 20.6 (1.3) | 9.7 (1.4) | 10.8 (7.7, 14) | |

| p-value | 0.01 | 0.71 | 0.074 | |

|

| ||||

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (SE)‡ | Currently in study | −22.4 (0.8) | −7.8 (1) | −14.6 (−16.5, −12.6) |

| Lost to follow-up | −20.1 (1) | −7.9 (1.1) | −12.2 (−14.7, −9.7) | |

| p-value | 0.082 | 0.96 | 0.13 | |

|

| ||||

| Stenosis Bothersomeness Index (SE)§ | Currently in study | −8 (0.3) | −2.8 (0.3) | −5.2 (−5.9, −4.5) |

| Lost to follow-up | −6.9 (0.4) | −3.5 (0.4) | −3.4 (−4.3, −2.5) | |

| p-value | 0.008 | 0.19 | 0.002 | |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, work status, depression, BMI, any neurofroamen L or R, joint problem, stomach problem, reflex deficit, number of moderate/severe stenotic levels, other** comorbidity, baseline stenosis bothersomeness, baseline score (for SF-36 and ODI), and center.

Treatment effect is the difference between the surgical and non-operative mean change from baseline.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Bothersomeness index range from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Other comorbidities include: stroke, cancer, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol, drug dependency, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, migraine, anxiety.

The final as-treated models controlled for the following covariates: age, sex, race, work status, body mass index, neuroforaminal stenosis, depression, osteoporosis, joint problems, duration of current symptoms, reflex deficit, number of moderately or severely stenotic levels, treatment preference, other comorbidities (see Table 3 footnote), baseline SF-36 and ODI scores, baseline Stenosis Bothersomeness score, and center.

Randomized Controlled Trial—Intention to Treat Analysis

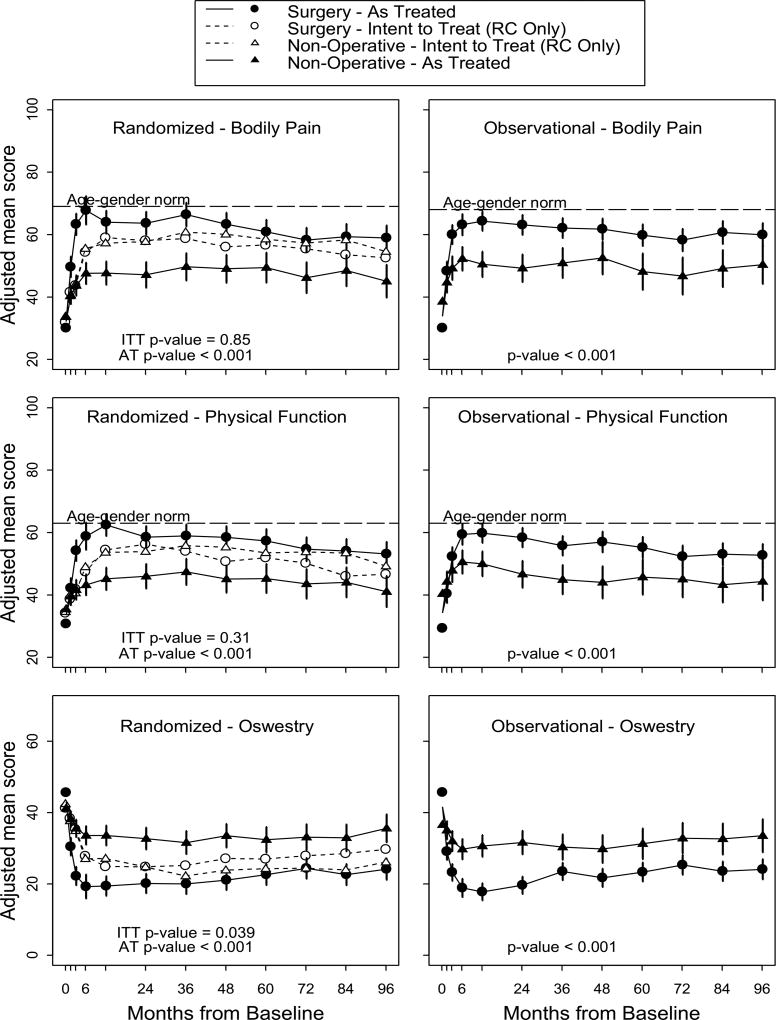

In the ITT analysis, the group randomized to nonoperative care improved significantly more on the ODI than the patients randomized to surgery in years 6, 7, and 8 (Supplemental Table 1). The nonoperative group also improved significantly more on the SF-36 PF at year 7. The magnitude of these differences was relatively low (i.e. approximately 5 points on the ODI and 7 points on the SF-36 PF). The nonoperative group improved significantly more than the surgery group in the global 8 year ITT analysis on the ODI (p=0.039, Figure 2). There were no significant differences in the global 8-year analyses for the other primary outcome measures.

Figure 2.

Main outcomes surgery vs. non-operative combined cohort

As Treated Analyses

The as-treated analysis demonstrated that patients treated surgically improved significantly more than those treated nonoperatively in the randomized, observational, and combined groups on all outcome measures at years 6, 7, and 8. In the combined analysis, the surgical group showed little degradation in outcomes from years 5 through 8 (Supplemental Table 1). At 8 years, the treatment effects of surgery were 11.8 (95% confidence interval (CI), 7.2 to 16.4) for SF-36 BP; 10.3 (95% CI, 5.9 to 14.7) for SF-36 PF; and −10.3 (95% CI, −13.6 to −6.9) for the ODI. The surgery group improved significantly more than the nonoperative group in the global 8-year as-treated analysis on all outcome measures (Figure 2).

Surgical Treatment and Complications

Among surgery patients with complete surgical data (n=406), 7% (n = 29) underwent decompression alone, 21% (n = 84) had PLF, 55% (n = 222) had PPS, and 17% (n = 71) had 360° fusion. The 8-year reoperation rate was 22% (91/406), with recurrent stenosis/progressive listhesis being the most common indication for re-operation.

At eight years, there were 33 deaths in the surgical group, compared with 53 expected deaths and 17 compared to 37 expected deaths in the nonoperative group based on age and sex-specific mortality data.25 The hazard ratio based on a proportional-hazards model adjusted for age was 1.2 (95% confidence interval, 0.63 to 2.1; p = 0.64). Of the 50 deaths observed in both groups, 2 were considered probably related to treatment: one patient died of respiratory distress 32 days after surgery, and the other died of sepsis 82 days after surgery.

Fusion Technique

Baseline characteristics of the three fusion groups are also summarized in Table 1. Comparison between the PLF and 360° treatment groups revealed the most pronounced differences. The 360° patients were younger, more likely to be employed and had less severe stenosis, with moderate/severe stenosis more likely to be localized to one stenotic level. The PLF patients reported more severe baseline neurologic deficits and were more likely to have multiple levels of moderate/severe central stenosis. A greater percentage of PPS patients had radiographic instability (greater than 10 degrees of rotation of 4 mm of translation on flexion-extension radiographs).

The mean operation time was shortest for PLF (157.6 minutes), in contrast to PPS (212 minutes) and 360° (273.7 minutes) (Table 4). Mean estimated blood loss was highest for PPS and lowest for PLF (654 mL vs. 507 mL). Patients undergoing 360° fusion had the lowest rate of dural tear (PLF = 11%; PPS = 11%; 360° = 1%; P=0.039). There were no significant differences between the groups in post-operative complications. Eight-year reoperation rate was 24% for PLF, 20% for PPS, and 24% for 360° (p=0.61).

Table 4.

Operative treatments, complications and events for DS 8yr fusion.

| PLF (n=84) |

PPS (n=222) |

360° (n=71) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-level fusion - no. (%) | 16 (19%) | 53 (24%) | 28 (39%) | 0.009 |

| Decompression level - no. (%) | ||||

| L2–L3 | 17 (20%) | 25 (11%) | 2 (3%) | 0.006 |

| L3–L4 | 51 (61%) | 113 (52%) | 17 (26%) | <0.001 |

| L4–L5 | 81 (96%) | 216 (97%) | 65 (96%) | 0.77 |

| L5-S1 | 31 (37%) | 60 (27%) | 19 (29%) | 0.25 |

| No. of levels decompresssed - no. of patients (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 27 (32%) | 87 (39%) | 42 (62%) | |

| 2 | 28 (33%) | 89 (40%) | 17 (25%) | |

| 3+ | 29 (35%) | 46 (21%) | 9 (13%) | |

| Operation time, minutes (SD) | 157.6 (58.7) | 212 (73.9) | 273.7 (89.4) | <0.001 |

| Blood loss, cc (SD) | 506.5 (390.7) | 654 (514.1) | 563.5 (397.4) | 0.037 |

| Blood replacement - no. (%) | ||||

| Intraoperative replacement | 22 (27%) | 83 (38%) | 28 (40%) | 0.13 |

| Post-operative transfusion | 12 (14%) | 55 (25%) | 13 (19%) | 0.11 |

| Length of hospital stay, days (SD) | 4.3 (3.4) | 4.8 (2.7) | 5.5 (3.6) | 0.038 |

| Postoperative immobilization: Brace/Corset - no. (%) | 44 (54%) | 101 (47%) | 50 (72%) | <0.001 |

| Intraoperative complications - no. (%)‡ | ||||

| Dural tear or cerebrospinal fluid leak | 9 (11%) | 25 (11%) | 1 (1%) | 0.039 |

| Vascular injury | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.70 |

| Other | 3 (4%) | 4 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0.57 |

| None | 72 (86%) | 193 (87%) | 69 (97%) | 0.039 |

| Postoperative complications and events - no. (%)§ | ||||

| Nerve root injury | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.71 |

| Wound dehiscence | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0.11 |

| Wound hematoma | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0.11 |

| Wound Infection | 5 (6%) | 5 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0.16 |

| Other | 4 (5%) | 26 (12%) | 5 (7%) | 0.14 |

| None* | 64 (77%) | 142 (65%) | 52 (74%) | 0.063 |

| Death within 6 weeks after surgery-no.(%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.17 |

| Death within 3 months after surgery-no.(%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.58 |

| Additional spine surgeries within 1 yr - no. (%)‖ | 5 (6%) | 12 (5%) | 5 (7%) | 0.87 |

| Additional spine surgeries within 2 yr | 12 (14%) | 23 (10%) | 7 (10%) | 0.62 |

| Additional spine surgeries within 3 yr | 14 (17%) | 28 (13%) | 9 (13%) | 0.66 |

| Additional spine surgeries within 4 yr | 15 (18%) | 31 (14%) | 9 (13%) | 0.64 |

| Additional spine surgeries within 5 yr | 16 (19%) | 32 (14%) | 11 (15%) | 0.63 |

| Additional spine surgeries within 6 yr | 18 (21%) | 37 (17%) | 12 (17%) | 0.63 |

| Additional spine surgeries within 7 yr | 19 (23%) | 40 (18%) | 16 (23%) | 0.59 |

| Additional spine surgeries within 8 yr | 20 (24%) | 43 (20%) | 17 (24%) | 0.61 |

| Recurrent stenosis / progressive listhesis | 9 (11%) | 23 (11%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Pseudarthrosis / fusion exploration | 1(NE)** | 3 (1%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Complication | 10 (12%) | 13 (6%) | 8 (11%) | |

| New condition¶ | 5 (6%) | 5 (2%) | 2 (3%) |

None of the following were reported: aspiration, nerve root injury, operation at wrong level.

Any reported complications up to 8 weeks post operation. None of the following were reported: bone graft complication, CSF leak, paralysis, cauda equina injury, pseudarthrosis.

None indicates no complications and no post-operative transfusion.

The post-surgical re-operation rates are Kaplan-Meier estimates.

One new stenosis occurred in the randomized cohort, two herniations and two stenoses occurred in the observational cohort.

Not estimable.

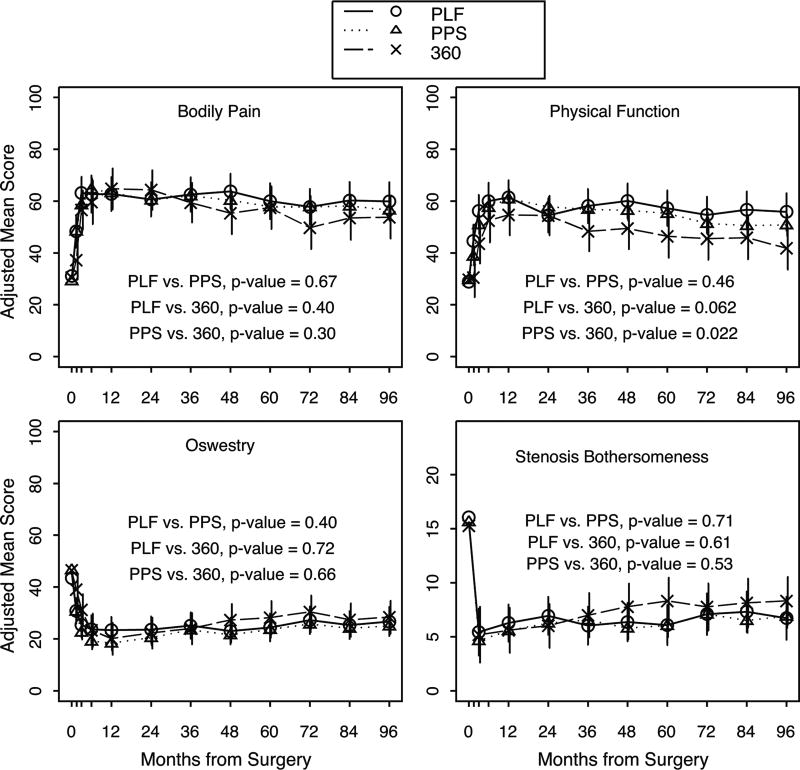

The time-weighted average outcomes from baseline through eight years demonstrated that PPS patients improved significantly more on the SF-36 physical function score compared to the 360° group (PPS = 24.5 [95% CI 21.7 to 27.3]; 360° = 18 [95% CI 11.6 to 24.4]; p = 0.022) (Figure 3). There was a trend towards the PLF group improving more on the SF-36 physical function score compared to the 360° patients, but the difference was not statistically significant (PLF = 26.8 [95% CI 21.6 to 32]; 360° = 18 [95% CI 11.6 to 24.4) p = 0.062].

Figure 3.

Outcomes for different fusion techniques

Discussion

Long-term surgical and non-operative outcomes from 5 to 8 years were similar to earlier outcomes for DS patients, with the as-treated analysis demonstrating significantly better outcomes for surgery compared to non-operative treatment. The ITT analysis showed significantly better outcomes on the ODI and SF-36 PF for the group randomized to nonoperative care at some of the later time points. However, this result is difficult to interpret due to the lack of consistency among outcomes and the high cross-over rates. Given that 54% of the patients randomized to non-operative treatment underwent surgery, while 28% of the patients randomized to surgery never had surgery, the results of the as-treated analysis, which were carefully controlled for potential confounders, may better reflect the comparative effectiveness of surgery.26

There are few studies with long-term outcomes comparable to SPORT. Outcomes were collected at eight and ten years on patients in the Maine Lumbar Spine Study (MLSS).4 For this mixed cohort of spinal stenosis patients with and without DS, the benefit of surgery at 4 years narrowed at 8- and 10-year follow-up. The surgery group maintained a significant advantage on leg pain and disability, but not on back pain or patient satisfaction at the long-term follow-up. Slatis et al. performed an RCT comparing surgery to non-operative treatment for stenosis with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis in 94 patients.27 At 6 years, the benefit of surgery was maintained for the ODI (treatment effect = 9.5) but not for leg and back pain. In contrast, the SPORT as-treated analysis showed a persistent advantage for surgery on all outcome measures out to 8 years. The 10 year 23% reoperation rate in MLSS was consistent with the 8 year 22% reoperation rate in SPORT.

In SPORT, surgical technique had minimal effect on clinical outcomes or reoperation rates. These findings at 8 years were similar to the findings at 4 years.28 To date, few other studies have focused on fusion techniques specific to patients with DS. Fischgrund et al. randomized DS patients to decompression and fusion with or without pedicle screw instrumentation and found no difference in two-year clinical outcomes between the two fusion groups, though there was a higher pseudoarthrosis rate in the uninstrumented group.7 Campbell et al.’s systematic review compared interbody fusion plus posterolateral instrumented fusion to posterolateral instrumented fusion alone for DS using the ODI and visual analog scale as the primary outcomes.29 No statistically significant differences were found between techniques. Although these studies do not provide direct comparison to our study, they suggest no advantage to more complex approaches to fusion in DS patients.

Two recent randomized controlled trials comparing decompression alone to decompression with posterolateral instrumented fusion reported conflicting results. Ghogawala et al. found better patient reported outcomes and a lower re-operation rate for patients treated with decompression and fusion.30 In contrast, Forsth et al. found no differences in patient reported outcomes or reoperation rates between the two surgical techniques.31 The decompression only group in SPORT was too small to allow for statistically robust comparison to fusion, so no direct comparison to these studies is possible.

Limitations

Non-adherence to the randomized treatment group is a major limitation of this study, reducing the power of the intent-to-treat analysis to demonstrate a treatment effect. Although the as-treated analysis was subject to confounding due to baseline differences between the groups, rigorous analyses controlled for these differences and yielded results similar to prior studies.2,8,14 However, confounding by unmeasured variables is not possible to control and could have affected the results. Patients who were lost to follow-up were older, less-well educated, sicker and had worse surgical outcomes over the first 2 years. Loss to follow-up of patients in the surgery group with worse short-term outcomes than those lost to follow-up in the nonoperative group raises concerns for overestimation of the surgical treatment effect. Additionally, the fusion types in the SPORT were not randomly assigned and selection bias may have affected these results.

Conclusion

This trial demonstrated a long-term advantage of surgical treatment for DS patients who presented with neurogenic claudication or radiculopathy consistent with imaging demonstrating spinal stenosis at the level of the listhesis. Fusion technique did not affect long term outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s).

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U01-AR45444) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funds were received in support of this work. The Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center in Musculoskeletal Diseases is funded by NIAMS (P60 AR062799)

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: grants.

References

- 1.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, et al. United States' trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992–2003. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:2707–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, Keller RB, et al. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study, Part III. 1-year outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1996;21:1787–94. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608010-00012. discussion 94-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Robson D, et al. Surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: four-year outcomes from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:556–62. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200003010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, et al. Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: 8 to 10 year results from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:936–43. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158953.57966.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malmivaara A, Slatis P, Heliovaara M, et al. Surgical or nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis? A randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000251014.81875.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridwell KH, Sedgewick TA, O'Brien MF, et al. The role of fusion and instrumentation in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:461–72. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199306060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischgrund JS, Mackay M, Herkowitz HN, et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective, randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. 1997 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies. Spine. 1997;22:2807–12. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199712150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herkowitz HN, Kurz LT. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. A prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:802–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1295–304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Chang LC, et al. Seven- to 10-year outcome of decompressive surgery for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1996;21:92–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199601010-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Tosteson A, et al. Long-term Outcomes of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Eight-Year Results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:63–76. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:794–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birkmeyer NJ, Weinstein JN, Tosteson AN, et al. Design of the Spine Patient outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2002;27:1361–72. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2257–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummins J, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Descriptive epidemiology and prior healthcare utilization of patients in The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial's (SPORT) three observational cohorts: disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2006;31:806–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000207473.09030.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, et al. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Jama. 1989;262:907–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware J, Sherbourne D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JJ. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: Nimrod Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daltroy LH, Cats-Baril WL, Katz JN, et al. The North American spine society lumbar spine outcome assessment Instrument: reliability and validity tests. Spine. 1996;21:741–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Patient satisfaction with medical care for low-back pain. Spine. 1986;11:28–30. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine. 1995;20:1899–908. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011. discussion 909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis four-year results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1329–38. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e0f04d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzmaurice G, Laird N, Ware J. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Philadelphia, PA: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deyo RA, Ciol MA, Cherkin DC, et al. Lumbar spinal fusion. A cohort study of complications, reoperations, and resource use in the Medicare population. Spine. 1993;18:1463–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1887–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slatis P, Malmivaara A, Heliovaara M, et al. Long-term results of surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomised controlled trial. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2011;20:1174–81. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1652-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdu WA, Lurie JD, Spratt KF, et al. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: does fusion method influence outcome? Four-year results of the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2351–60. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b8a829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell RC, Mobbs RJ, Lu VM, et al. Posterolateral Fusion Versus Interbody Fusion for Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Global Spine J. 2017;7:482–90. doi: 10.1177/2192568217701103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghogawala Z, Dziura J, Butler WE, et al. Laminectomy plus Fusion versus Laminectomy Alone for Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1424–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forsth P, Olafsson G, Carlsson T, et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Fusion Surgery for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1413–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.