Abstract

Daily PrEP is highly effective at preventing HIV-1 acquisition, but risks of long-term tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine (TDF-FTC) include renal decline and bone mineral density decrease in addition to initial gastrointestinal side effects. We investigated the impact of TDF-FTC on the enteric microbiome using rectal swabs collected from healthy MSM before PrEP initiation and after 48 to 72 weeks of adherent PrEP use. The V4 region of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing showed that Streptococcus was significantly reduced from 12.0% to 1.2% (p = 0.036) and Erysipelotrichaceae family was significantly increased from 0.79% to 3.3% (p = 0.028) after 48–72 weeks of daily PrEP. Catenibacterium mitsuokai, Holdemanella biformis and Turicibacter sanguinis were increased within the Erysipelotrichaceae family and Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus mitis were reduced. These changes were not associated with host factors including PrEP duration, age, race, tenofovir diphosphate blood level, any drug use and drug abuse, suggesting that the observed microbiome shifts were likely induced by daily PrEP use. Long-term PrEP resulted in increases of Catenibacterium mitsuokai and Holdemanella biformis, which have been associated with gut microbiome dysbiosis. Our observations can aid in characterizing PrEP’s side effects, which is likely to improve PrEP adherence, and thus HIV-1 prevention.

Introduction

Truvada, a fixed-dose combination of the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) plus emtricitabine (FTC), was approved for daily HIV-1 pre exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in 2012, and by 2015 more than 79,000 people in US are estimated to have started TDF-FTC for PrEP1. Daily PrEP is highly effective at preventing HIV-1 infection, reducing HIV-1 acquisition by over 90% in MSM2. As a key part of the national HIV/AIDS strategy, PrEP use is expected to continue to increase, and thus understanding the side effects of widespread PrEP adoption is an important task.

In randomized studies in long-term PrEP users, kidney function decline3 and bone mineral density decrease4 have been reported, which are in concordance with the observations among TDF-treated HIV-infected individuals5,6. Renal tubular toxicity of TDF has been suggested as a mechanism for kidney abnormalities7. TDF-induced bone mineral density decreases have been explained by osteoblast gene expression changes8 and tubular dysfunction and resulting phosphaturia9. We may gain further insights on these long-term PrEP side effects by profiling the gut microbiome as the human gut microbiota is reported to be correlated with both chronic kidney disease and osteoporosis. Increases in uremic toxins and inflammation among chronic kidney disease patients were in part due to the gut microbiome’s role in the fermentation of short-chain fatty acids10. Several studies reported a significant association between the intestinal microbiota, calcium absorption, and bone health11,12. As suggested from these findings, study of the microbiome profile, in the absence of HIV infection during PrEP, may provide an important correlate for addressing long-term side effects attributable to TDF-FTC use.

A direct interaction between a drug and the enteric microbiome has been demonstrated for different classes of drugs13–15. Other drugs may also have indirect and unintended antimicrobial activities16. Indeed, a recent population-level study found medication to have the greatest influence on gut microbiome composition, compare to other covariates such as gender, diet, and health status17.

In this study, we investigated the impact of PrEP on the enteric microbiome using serial specimens collected from healthy individuals before initiation of PrEP (baseline) and after 48 to 72 weeks of adherent PrEP use in the California Collaborative Treatment Group study 595 (NCT01761643). CCTG 595 was a randomized controlled trial in high risk MSM and transgender women to compare the impact of daily text messaging to standard care on daily TDF-FTC adherence18. We chose study participants with documented adequate adherence to PrEP and these are optimal for investigating the direct impact of daily PrEP on the enteric microbiome profile. By performing next-generation sequencing of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene, we assessed the relative abundance of each family and genus before and after PrEP administration and identified microbiome shifts after long-term PrEP. In addition, we conducted long-read next-generation sequencing of bacterial 16S-23S rRNA to identify which species are impacted by long-term daily PrEP.

Results

We compared the microbiome composition of 8 study participants’ rectal specimens before PrEP administration and after 48 to 72 weeks of adherent PrEP use. Table 1 lists each study participant’s age, race, duration of PrEP use, tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) level measured at 48 weeks post PrEP initiation, and any other drug usage and abuse. The next-generation sequencing reads of the V4 region of the 16s ribosomal RNA gene were obtained and processed as described in Methods. The number of sequencing reads before and after processing are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information of 8 PrEP study participants.

| Participant | PrEP Duration | Age | Race | TFV-DP (fmol/punch) | Any drug use | Any drug abuse | Rectal douching |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WWS | 72 | 39 | Asian | 2059 | Yes | No | No |

| XNT | 72 | 28 | White | 1755 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| WD5 | 72 | 52 | White | 1620 | No | No | Yes |

| WT9 | 72 | 29 | White | 1447 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| XRQ | 72 | 33 | White | 1417 | No | No | Yes |

| 7RJ | 48 | 22 | Multiple | 1163 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7FX | 60 | 38 | Black | 1151 | Yes | No | Yes |

| 7NR | 48 | 37 | Multiple | 996 | Yes | No | Decline* |

*Declined to answer.

PrEP-induced changes in the microbiome composition were assessed with two methods. First, we statistically addressed the impact of PrEP on the microbiome composition using a permutation test. To control for the small sample size, we performed a permutation test in which we randomly permuted all specimens’ PrEP status (pre-PrEP or post-PrEP) to identify any meaningful differences in the microbiome composition at the family and genus levels. An empirical p-value was obtained for each family or genus through 100,000 PrEP status permutations. We also conducted a paired-permutation test by permuting each individual’s PrEP status and evaluating the chance to observe the measured t-statistic, compared to the t-statistic distribution for all possible 28 arrangements. Second, we calculated the log fold change of each family or genus, defined as log2 of the ratio between mean abundances after and before PrEP.

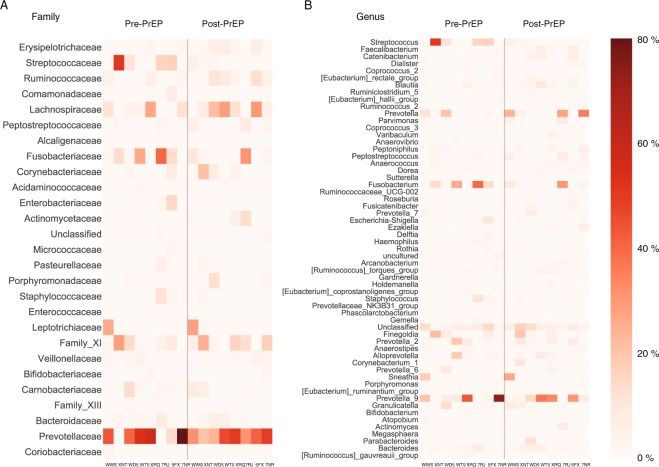

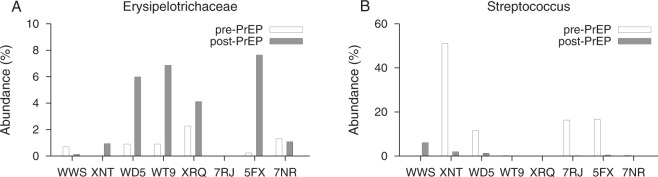

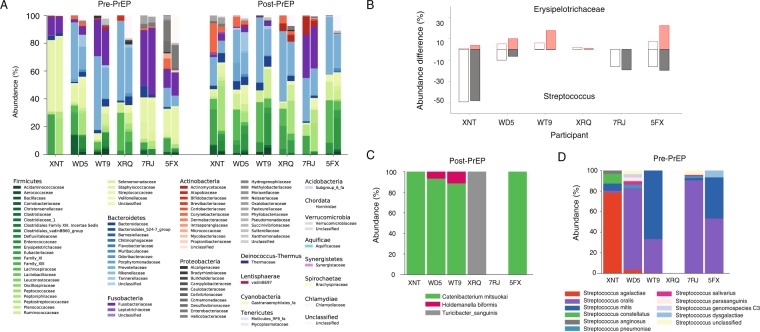

Figure 1 plots the abundance of each family and genus from eight subjects before and after PrEP, sorted by the empiric p-value obtained from the permutation test. At the family level, the permutation test indicated that the abundances of Erysipelotrichaceae and Streptococcaceae were statistically significantly altered with a minimum of 48 weeks PrEP administration (p = 0.028 and p = 0.039, respectively). Erysipelotrichaceae and Streptococcaceae remained significantly different under the paired-permutation test (p = 0.031 and p = 0.039, respectively). Pre-PrEP specimens had 0.79% of Erysipelotrichaceae on average, however, its relative abundance was increased to 3.3% after PrEP, resulting in a mean log2(fold change) of 2.1. As shown in Fig. 2A, six out of eight participants showed Erysipelotrichaceae increase after PrEP. On the contrary, relative abundance of Streptococcaceae was decreased after PrEP with log2 (fold change) of −3.3. Four participants showed a considerable reduction of Streptococcaceae with an over 10 percent decrease.

Figure 1.

Microbial abundance profiles before and after long-term PrEP with TDF-FTC. (A) Each family’s relative abundance within eight CCTG-595 study participants before and after PrEP. The microbiome profile was determined by MiSeq high-throughput sequencing of the V4 region of the 16s ribosomal RNA gene. Families were sorted by the empirical p-value from the permutation test. The level of Erysipelotrichaceae significantly increased with 48–72 weeks PrEP administration (p = 0.028). Streptococcaceae level significantly decreased after PrEP treatment (p = 0.039). (B) Each genus abundance for eight participants before and after PrEP, sorted by the permutation test p-value. The relative abundance of Streptococcus significantly decreased after PrEP treatment (permutation test, p = 0.036).

Figure 2.

Erysipelotrichaceae and Streptococcus abundance changes by TDF-FTC. (A) The Erysipelotrichaceae abundance before and after PrEP for each of eight CCTG 595 study participants who were on daily PrEP for 48–72 weeks. The average abundance of Erysipelotrichaceae was increased from 0.79% to 3.3%, resulting in a mean log2 (fold change) of 2.1. Both permutation and paired-permutation tests indicate a statistically significant increase in the relative abundance of Erysipelotrichaceae after PrEP (p = 0.028 and p =0.031, respectively). (B) The Streptococcus abundance before and after PrEP for each of eight study participants. On average, the relative abundance of Streptocuccus was decreased from 12.0% to 1.2% after a minimum of 48 weeks PrEP treatment (permutation test p = 0.036 and paired-permutation test, p = 0.035). The resulting mean log2 (fold change) was −3.3.

At the genus level, Streptococcus was significantly reduced after PrEP administration (permutation test, p = 0.036 and paired-permutation test, p = 0.035). The average relative abundance of Streptococcus across eight study participants was 12.0% before PrEP initiation. However, after 48–72 weeks of daily TDF-FTC, the average abundance was reduced to 1.2%. Figure 2B compares the Streptococcus abundance before and after PrEP for each of eight study participants. The mean log2(fold change) over eight participants was −3.3 and we observed more than a 10 percent reduction in Streptococcus level in four participants (Fig. 2B). In particular, participant XNT showed a reduction from 51% to 1.9%. Within the Streptococcaceae family, Streptococcus was the dominant genus (>99%) in all eight participants, resulting in significant shifts at both the family and genus levels. Table 2 lists each family’s p-value and fold change.

Table 2.

Abundance difference in given family and genus before and after minimum 48 weeks of PrEP administration.

| Family | log2 (fold change) | p value | Genus | log2 (fold change) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erysipelotrichaceae | 2.08 | 0.028 | Streptococcus | −3.27 | 0.036 |

| Streptococcaceae | −3.27 | 0.039 | Faecalibacterium | 1.77 | 0.054 |

| Ruminococcaceae | 1.43 | 0.058 | Catenibacterium | 2.96 | 0.056 |

| Comamonadaceae | Inf | 0.10 | Roseburia | 1.61 | 0.061 |

| Lachnospiraceae | 0.81 | 0.16 | Dialister | 1.77 | 0.062 |

| Peptostreptococcaceae | 1.16 | 0.17 | Eubacterium_rectale_group | 1.85 | 0.081 |

| Alcaligenaceae | −1.24 | 0.18 | Coprococcus_2 | −7.28 | 0.083 |

| Fusobacteriaceae | −1.02 | 0.18 | Blautia | 1.49 | 0.092 |

| Actinomycetaceae | 3.54 | 0.18 | Ruminiclostridium_5 | 2.97 | 0.096 |

| Acidaminococcaceae | 1.00 | 0.19 | Eubacterium_hallii_group | 1.15 | 0.12 |

| Corynebacteriaceae | 1.51 | 0.20 | Varibaculum | 6.96 | 0.12 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | −3.66 | 0.21 | Ruminococcus_2 | 1.63 | 0.13 |

| Micrococcaceae | Inf | 0.24 | Arcanobacterium | 7.20 | 0.13 |

| Enterococcaceae | −4.59 | 0.27 | Parvimonas | 3.25 | 0.13 |

| Pasteurellaceae | −0.94 | 0.27 | Haemophilus | −3.52 | 0.13 |

| Porphyromonadaceae | 2.33 | 0.28 | Coprococcus_3 | 1.35 | 0.14 |

| Staphylococcaceae | −2.34 | 0.28 | Prevotella | 1.23 | 0.14 |

| Leptotrichiaceae | 0.24 | 0.29 | Peptoniphilus | 1.14 | 0.15 |

| Family_XI | 0.41 | 0.30 | Dorea | 0.78 | 0.16 |

| Veillonellaceae | 0.33 | 0.35 | Peptostreptococcus | 1.31 | 0.16 |

| Bifidobacteriaceae | −0.55 | 0.36 | Anaerovibrio | −3.29 | 0.16 |

| Carnobacteriaceae | −0.40 | 0.39 | Anaerococcus | 1.07 | 0.16 |

| Family_XIII | −1.42 | 0.41 | Corynebacterium_1 | 1.51 | 0.17 |

| Bacteroidaceae | −0.062 | 0.48 | Sutterella | −1.27 | 0.17 |

| Prevotellaceae | 0.022 | 0.48 | Fusobacterium | −1.02 | 0.17 |

| Coriobacteriaceae | −0.48 | 0.50 | Ruminococcaceae_UCG-002 | 1.37 | 0.18 |

The p value from the permutation test is presented.

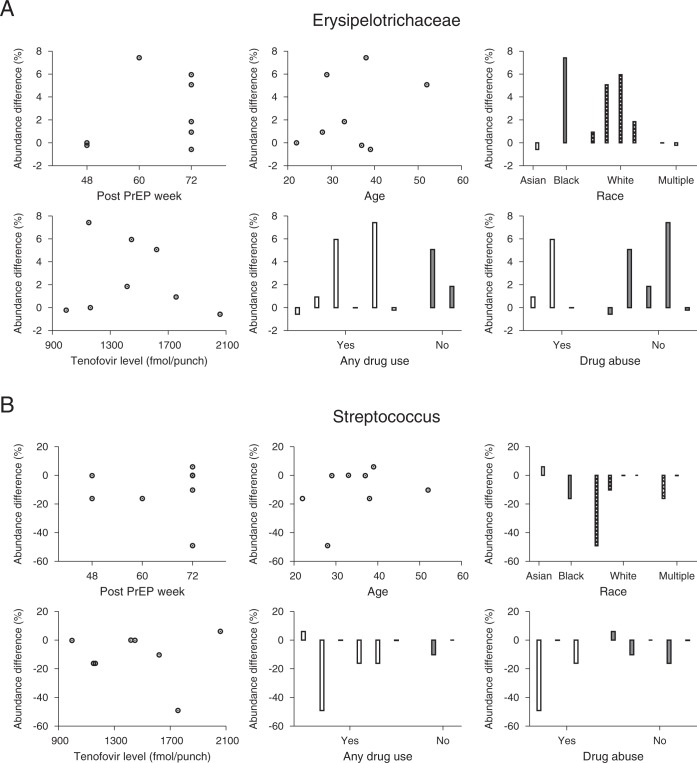

We next examined the associations between host factors and microbiome abundance changes. Figure 3A plots Erysipelotrichaceae abundance difference before and after PrEP as a function of PrEP duration, age, race, TFV-DP level, any drug use status and drug abuse status. The Erysipelotrichaceae change was not dependent on either PrEP duration (Spearman’s correlation ρ = 0.21 and p = 0.62) or age (ρ = 0.071 and p = 0.88). The abundance difference was not correlated with TFV-DP levels at 48 weeks after PrEP (ρ = −0.19 and p = 0.66). The Erysipelotrichaceae abundance difference was not sensitive to race (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.37) and was not affected by any drug use (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 0.51) or drug abuse (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 1.0). Likewise, the Streptococcus change was not correlated with PrEP duration (ρ = 0.33 and p = 0.42). As shown in Fig. 3B, age was not associated with abundance change (ρ = 0.33 and p = 0.43). The abundance change was not sensitive to race (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.11) and was not correlated with TFV-DP levels at 48 weeks after PrEP (ρ = 0.21 and p = 0.62). The Streptococcus abundance difference was not affected by any drug use (p = 0.64) or drug abuse (p = 0.39). This lack of significance of the differences might be due to the small sample size, however, Fig. 3 does not indicate any trends in the associations.

Figure 3.

Microbiome changes after TDF-FTC and host factors. (A) Eight individuals’ Erysipelotrichaceae abundance differences before and after PrEP. The Erysipelotrichaceae abundance difference was not dependent on the duration of PrEP (Spearman’s correlation ρ = 0.21 and p = 0.62). Age did not significantly correlate with the Erysipelotrichaceae abundance change after PrEP (ρ = 0.071 and p = 0.88). The Erysipelotrichaceae abundance change was not sensitive to race (1 Asian vs. 1 Black vs. 4 Whites vs. 2 Multiples, Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.37) and was not correlated with intracellular tenofovir disphosphate level measured at 48 weeks after PrEP initiation (ρ = −0.19 and p = 0.66). The α-diversity abundance change did not differ between participants with and without any other drug use (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 0.51) and between participants with and without drug abuse (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 1.0) (B) The Streptococcus abundance change was not dependent on the duration of PrEP (Spearman’s correlation ρ = 0.33 and p = 0.42). Streptococcus change and age were not statistically correlated in the eight subjects (ρ = 0.33 and p = 0.43). Streptococcus abundance change was not sensitive to race (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.11) and was not correlated with the tenofovir diphosphate level at 48 weeks after PrEP (ρ = 0.21 and p = 0.62). The Streptococcus abundance change was not affected by any drug use (p = 0.64) or drug abuse (p = 0.39).

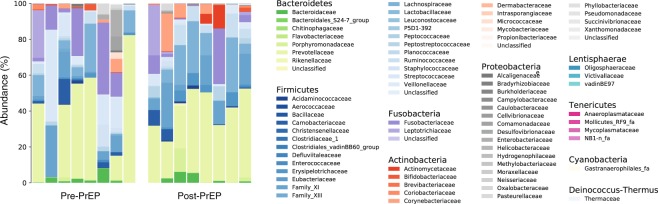

Figure 4 compares the family composition of eight individuals before and after PrEP. Consistent with previous reports on the healthy human gut microbiome profiles19,20, the CCTG 595 cohort was dominated by the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. Prevotellaceae was the most dominant family in all specimens, except three pre-PrEP samples (XNT, 5FX, and 7RJ), with average abundance of 36% across all 16 specimens. Before the initiation of PrEP, the most prevalent family in participant XNT and participant 5FX was Streptococcaceae with relative abundances of 51% and 17%, respectively. The most prevalent family in participant 7RJ prior to PrEP initiation was Fusobacteriaceae with 40% abundance. Across 16 specimens from eight participants, the average abundance of Lachnospiraceae (11%), Fusobacteriaceae (9.1%), Family_XI (8.8%), and Streptococcaceae (6.6%) were observed to be greater than five percent.

Figure 4.

The microbial family composition in eight individuals before and after TDF-FTC PrEP. Subjects are displayed in the pre-PrEP and post-PrEP panels from left to right as follows: WWS, XNT, WD5, WT9, XRQ, 7RJ, 5FX, and 7NR. The phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were dominant in all 16 specimens. Prevotellaceae was the most abundant family in all specimens except three pre-PrEP specimens (XNT, 7FX, and 7RJ), with average abundance of 36%. Streptococcaceae was the most abundant family in pre-PrEP sample of participants XNT (51%) and 5FX (17%) and Fusobacteriaceae was the most abundant family in participant 7RJ’s pre-PrEP specimen (40%). The average relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae (11%), Fusobacteriaceae (9.1%), Family_XI (8.8%), and Streptococcaceae (6.6%) were observed to be greater than five percent across 16 specimens from eight participants.

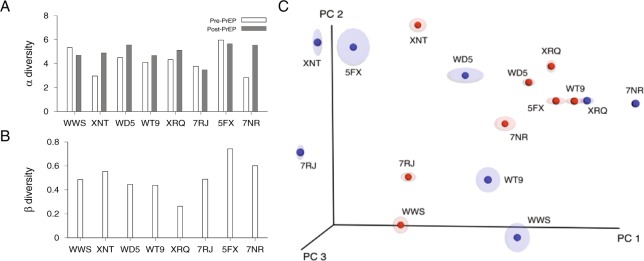

Each participant’s overall microbial diversity was comparable before and after PrEP. Microbiome diversity within a single specimen was assessed by α diversity, Shannon diversity index. The dissimilarity between a pair of specimens was assessed by β diversity which accounts for phylogenetic tree distances of microbial sequences in a pair of specimens. As shown in Fig. 5A, the average α diversity was 4.22 before PrEP and 4.95 after PrEP (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.15). We plotted the β diversity of each participant’s paired specimens in Fig. 5B. Across 8 pairs, The average β diversity across 8 pairs was 0.68 and the paired specimens of the participant XRQ showed the lowest level of β diversity. The β diversity between each participant’s pre and post-PrEP specimens was smaller than the β diversity of pre-PrEP specimen pairs of different individuals (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 0.015). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) demonstrated that the pre-PrEP and post-PrEP specimens did not form distinct clusters (Fig. 5C). The principal coordinate analysis indicates that there is no global shift in the microbiota between the pre and post PrEP specimens. Individual family and genus abundance changes were inquired through permutation tests in this study, observing that Erysipelotrichaceae and Streptococcus levels were significantly shifted by PrEP.

Figure 5.

α diversity and β diversity. (A) Within specimen microbial diversity was measured by α-diversity (Shannon diversity index). Each participant’s pre-PrEP specimen’s α diversity is compared with post-PrEP specimen’s α diversity. The α diversity did not change significantly with PrEP treatment (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.15). (B) Microbial β diversity was measured between each participant’s pre and post specimens (8 pairs). The weighted UniFrac statistics were computed using QIIME43. (C) Microbial community variation was represented by principal coordinate analysis of weighted UniFrac distances among specimens. Specimen dissimilarities were projected onto the first three principal coordinate dimensions where pre-PrEP specimens are colored in blue and post-PrEP specimens are in red.

Next we performed full-length 16S-23S rRNA long read sequencing to identify which species in Erysipelotrichaceae family and Streptococcus genus were affected by long-term PrEP. Figure 2 showed that participants XNT, WD5, WT9, XRQ, 7RJ, 5FX had changes in the abundance of either Erysipelotrichaceae or Streptococcus and from these participants, we obtained a total of 3363 reads of the 16S-23S rRNA region for species identification (Supplementary Table S2). Figure 6A compares the family composition of pre-PrEP and post-PrEP specimens for both v4–16S short read sequencing and 16S-23S long read sequencing. The overall family profiles were similar; the family composition root-mean-square-error between v4-16S and 16S-23S sequencings ranged from 0.016 to 0.051 across each of 12 specimens from participants XNT, WD5, WT9, XRQ, 7RJ, 5FX. Observable differences in the microbiome profiles for the two sequencing methods were also present (Fig. 6A). We compared abundance changes in Erysipelotrichaceae and Streptococcus measured by v4-16S sequencing and 16S-23S long read sequencings (Fig. 6B). Post-PrEP Erysipelotrichaceae increase measured by 16S-23S sequencing was more prominent than that by v4-16S sequencing. Streptococcus decrease measured by 16S-23S sequencing was consistent with that measured by v4-16S sequencing. Erysipelotrichaceae increase after PrEP was mainly driven by the species Catenibacterium mitsuokai. Holdemanella biformis and Turicibacter sanguinis were also detected within this family (Fig. 6C). Before PrEP initiation, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus mitis were the dominant species in the Streptococcus genus (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Species identification using full-length 16S-23S sequencing. (A) Microbiome Family compositions measured by v4 region of 16s rRNA sequencing (left) and 16S-23S rRNA sequencing (right) for participants, XNT, WD5, WT9, XRQ, 7RJ, and 5FX at pre-PrEP and post-PrEP. (B) Abundance differences between pre-PrEP and post-PrEP specimens for Erysipelotrichaceae (red) and Streptococcus (grey) for study participants, XNT, WD5, WT9, XRQ, 7RJ, and 5FX. The abundance difference of Erysipelotrichaceae measured by 16S-23S sequencing (filled red boxes) was increased in four individuals, compared to the abundance difference obtained from v4-16s sequencing (empty red boxes). The abundance difference of Streptococcus measured by 16S-23S sequencing (filled grey boxes) was consistent with that measured by v4-16s sequencing (empty grey boxes). (C) Species composition of Erysipelotrichaceae family measured from participants XNT, WD5, WT9, XRQ, 7RJ, and 5FX after a minimum of 48 weeks PrEP. Within subjects XNT, WD5, WT9, and 5FX, Catenibacterium mitsuokai was the most dominant species in Erysipelotrichaceae family. Turicibacter sanguinis was detected in participant XRQ and Holdemanella biformis was detected in WD5 and WT9. (D) Species composition of Streptococcus genus measured from the above study participants before PrEP initiation. Streptococcus agalactiae (red) was most abundant in participant XNT, Streptococcus oralis (purple) was dominant in WD5, 7RJ and 5FX, and Streptococcus mitis (blue) was dominant in WT9.

Discussion

PrEP use has increased substantially since 2012 and characterizing its long-term side effects is the first step to improve PrEP regimen and adherence1. Two well-known side effects of TDF are kidney function decline and bone mineral density decrease5,6. Recent studies reported that long-term PrEP users showed impaired kidney function3 and a decrease in bone mineral density4. The human gut microbiota is known to be correlated with both chronic kidney disease and osteoporosis. Increases in uremic toxins and inflammation among chronic kidney disease patients were in part due to the gut microbiome’s role in the fermentation of short-chain fatty acids, which have an anti-inflammatory impact21. Intestinal bacterial overgrowth was associated with changes in essential metabolites for bone processes such as calcium, vitamin K, and vitamin B12. During a state of gut microbiome dysbiosis, gut microbiota can affect the absorption of calcium and vitamin D, which can lead to osteoporosis22. Our study profiled microbiome structures before and after long-term PrEP to identify microbiota signatures altered by TDF-FTC daily use, which have the potential to affect the kidney and bone health.

We observed that Streptococcus was significantly reduced from 12.0% to 1.2% and the Erysipelotrichaceae was significantly increased from 0.79% to 3.3% after a minimum of 48 weeks of daily PrEP among CCTG-595 study participants. This cohort is at high risk of HIV-1 infection and has extensive demographic and clinical details including PrEP adherence data. Both Streptococcus and Erysipelotrichaceae abundance changes were not associated with host factors including PrEP duration, age, race, TFV-DP level, any drug use status and drug abuse status, suggesting that the observed microbiome shifts were potentially induced by daily TDF-FTC use.

Both commensal and pathogenic species of Streptococcus have been found to coexist in the healthy human gut microbiome23. Members of the Streptococcus genus have gut-protective influences. Streptococcus lactis, Streptococcus cremoris, and Streptococcus thermophilus are commonly found in both natural and commensal probiotics24,25. Our 16S–23S long read sequencing revealed that Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus mitis were the closest species significantly greater in pre-PrEP specimens compared to post-PrEP specimens. Streptococcus agalactiae has been reported to be a harmless commensal bacterium, colonized in the intestine26. Streptococcus oralis and Streptococcus mitis are both commensal bacterial which predominately reside in the oral cavity27 but these species were also found in fecal samples28.

A common enteric side effect associated with TDF-FTC PrEP is a frequently cited reason for poor adherence to PrEP schedules29. However, this adverse effect, termed “PrEP start up syndrome”, is usually observed within the first month of TDF-FTC PrEP and resolves spontaneously by 3 months of treatment30,31. However, our post-PrEP specimens were collected 48–72 weeks after PrEP initiation. Therefore, a direct association between the enteric side effects and Streptococcus reduction should be further investigated at the time of PrEP start up syndrome. Additionally, the observed microbiota differences found using rectal swab specimens may not be comparable to those from other specimen types, collected from different gastrointestinal sites using mucosal biopsies32,33.

TDF-FTC also appeared to significantly increase the level of Erysipelotrichaceae, a family of bacteria that many species are considered opportunistic pathogens. Erysipelotrichaceae has been studied in conjunction with colorectal cancer and metabolic disorders34. Erysipelotrichaceae was significantly enriched in patients with colorectal cancer, compared to healthy controls35. Similarly, an increase in Erysipelotrichaceae abundance was reported in colorectal tumor-bearing mice36. Additionally, Erysipelotrichaceae was increased in obese individuals37. Our long read sequencing showed that Catenibacterium mitsuokai, Holdemanella biformis and Turicibacter sanguinis were bacterial species increased after long-term PrEP within Erysipelotrichaceae family. Both Catenibacterium mitsuokai and Holdemanella biformis were associated with gut microbiome dysbiosis caused by high fat and high sugar diet38 and an unhealthy fasting lipid profile39. Collectively, we speculate that the observed increase in Erysipelotrichaceae in the long-term PrEP treated cohort has a potential to contribute to an increased the risk of colorectal cancer and metabolic disorders, while this increase was due to other factors including dietary factors. This speculation is worth further investigation with long-term follow-up of PrEP treated individuals.

In conclusion we observed that Streptococcus were decreased and Erysipelotrichaceae were increased following daily TDF-FTC for PrEP. Because this study is limited by the small population size, these microbiome shifts should be further examined in a large cohort in conjunction with long-term outcomes. Identifying PrEP microbiota signatures is an important step toward treating and preventing side effects, which is likely to improve PrEP adherence, and thus HIV-1 prevention.

Methods

Study participants

Self-collected rectal swab specimens from eight individuals at baseline (pre-PreP) and after taking TDF-FTC daily for 48 to 72 weeks in the California Collaborative Treatment Group (CCTG) study 595 (NCT01761643) were examined18. Participants were given a tube with a sterile Dacron rectal swab, along with safety precautions and instructions for rectal swab self-collection. The rectal swab was immediately placed in a sterile 15 ml plain conical tube without media, and the screw cap was secured. The tube containing the sample was transported to the laboratory at room temperature and frozen at −80 °C within two hours of collection. CCTG 595 was a randomized controlled trial in high risk MSM and transgender women to compare the impact of daily text messaging to standard care on adherence to daily TDF-FTC18. Regimen adherence was assessed at 48 weeks by testing dried blood spots for tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP). This study included only participants with intracellular TFV-DP levels greater than 719 fmol/punch at week 48 weeks, a level associated with taking four or more doses of TDF a week40.

Alcohol and substance use were assessed using the SCID substance use screening questionnaire, DAST-10, and AUDIT questionnaires. None of the participants reported diarrhea. The participants’ dietary intake information is not available, which can be an important factor for microbial composition. Six of eight participants reported rectal douching at baseline, one participant reported no use of rectal douching, and one participant declined to answer. All participants signed an informed consent document subject to approval at each site’s IRB (University of Southern California, University of California, San Diego, and Harbor-University of California, Los Angeles). All the procedures and experiments were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Microbiome DNA extraction

The previously frozen swabs were placed in a sterile 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube and the excess swab handle was removed using sterile razor blades or scissors. Microbiome DNA was extracted using the Omega Mag-Bind Universal Pathogen DNA Kit (OMEGA bio-tek). Glass beads, 700 µL of SLX-Mlus Buffer were added to the thawed swab specimen. After 1 minute of vortexing, the tube was centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 minutes. 250 µL of the supernatant was collected, 275 µL SLX-Mlus Buffer was added, and heated to 65 °C for 10 minutes and 95 °C for 10 minutes. Specimens were vortexed at maximum speed using a horizontal adapter (Qiagen) for 8 minutes. After the elution, specimens were purified and concentrated using a Clean & Concentrator-5 kit (Zymo Research). The sample concentration was measured using PicoGreen (Invitrogen).

16S ribosomal RNA sequencing

The next-generation sequencing library of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was constructed by the following procedures. The extracted microbiome DNA was amplified using primers 515F-over (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 805R-over (5′- GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) in a reaction volume of 20 µL (5 µL of 0.2 ng/ µL extracted DNA, 13 µL AccuStart II PCR ToughMix, 0.25 µL of 20 µM 515F-over, 0.25 µL of 20 µM 805R-over and 1.5 µL nuclease-free water). The PCR condition was at 94 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 60 °C for 30 seconds, then 70 °C for 90 seconds with a final extension at 70 °C for 10 minutes. The PCR product was purified using Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter). The index PCR was then performed using primers S5xx (5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACxxxxxxxxTCGTCGGCAGCGTC-3′) and N7xx (5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATxxxxxxxxGTCTCGTGGGCTCGG-3′) in a reaction volume of 50 µL (4 µL of purified PCR product, 25 µL AccuStart II PCR ToughMix, 16 µL nuclease-free water, 2.5 µL of 4 µM S5xx and 2.5 µL of 4 µM N7xx). The PCR condition was at 94 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 8 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 45 °C for 30 seconds, 70 °C for 120 seconds and 10 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 60 °C for 30 seconds, 70 °C for 120 seconds with a final extension at 70 °C for 10 minutes. The PCR product was purified using Agencourt AMPure Xp (Beckman Coulter). Each sample concentration was determined using PicoGreen (Invitrogen), normalized and pooled and sent to the University of California, Los Angeles Technology Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics for Illumina MiSeq sequencing.

16S–23S ribosomal RNA sequencing

We performed 16S-23S rRNA long read sequencing on pre-PrEP and post-PrEP specimens from participants XNT, WD5, WT9, XRQ, 7RJ, 5FX. Additionally, a microbiome standard (ATCC, MSA-1001) consisting of 10 control strains was sequenced. Each participant’s extracted microbiome DNA (as described above) was amplified using primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 2409R23 (5′-GACATCGAGGTGCCAAAC-3′), targeting around 4500 base long 16S-23S rRNA region. PCR was performed in a reaction volume of 20 µL (5 µL of 0.2 ng/ µL extracted DNA, 13 µL of 2x AccuStart II PCR ToughMix, 1.5 µL nuclease-free water, 0.25 µL of 20 µM 27 F and 0.25 µL of 20 µM 2409R23). The PCR condition was 94 °C for 3 minutes, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 60 °C for 30 seconds, 70 °C for 5 minutes, and a final extension at 70 °C for 10 minutes. The PCR product was purified with 1.8x Ampure XP Beads, washed twice with 70% ethanol, and eluted in 20 µL of nuclease free water.

The purified samples were then set up for an index PCR to barcode each sample using primers, 27Fxx (5′-xxxxxxxxxxxxAGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 2409R23xx (5′-xxxxxxxxxxxxGACATCGAGGTGCCAAAC-3′). The index PCR was performed in a 50 µL reaction volume with 5 µL of purified PCR product, 25 µL AccuStart II PCR ToughMix, 17.6 µL nuclease-free water, 1.2 µL of 4 µM 27Fxx and 1.2 µL of 4 µM 2409R23xx. The PCR condition was at 94 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 10 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 63 °C for 20 seconds, 70 °C for 5 minutes, and a final extension at 70 C for 10 minutes. The index PCR condition for specimen pre-PrEP 5FX was modified by increasing primer volumes (2.5 µL), increasing the purified PCR product volume (7 µL), lowering the annealing temperature (60 °C), and increasing annealing time (60 °C for 30 seconds).

A PicoGreen assay was performed to determine the concentration of each sample. Equimolar amounts of each of 13 samples were pooled and shipped overnight on dry ice to RTL genomics for PacBio sequencing. After arrival, the samples were checked for concentration using the dsDNA Broad Range DNA kit on the Qubit Fluorometer 3.0 and quality checked with a Fragment Analyzer by Advanced Analytical Technologies using the High Sensitivity Large Fragment 50KB Analysis kit, which were subject to SMRTbell library preparation for PacBio Sequencing. This process began with a 0.5x Ampure PB Purification A total of 600 ng of DNA was used for creating circularized double stranded DNA templates by ligating hairpin adaptors to each side of templates. Following the overnight ligation, the circular templates were purified with AMPure PB Beads and SMRTbell sequencing primers were annealed to the adaptors. The dsDNA templates were then prepared for loading with a final concentration of 6 pM to initiate SMRTbell template sequencing.

Sequence data analysis

The forward and reverse reads obtained from the MiSeq sequencing run were assembled using the command, make.contigs in MOTHUR41. The obtained fasta file was screened for the presence of ambiguous bases and any reads with such bases were discarded. The reads were then subjected to taxonomy annotation after putative chimeric sequences were removed using chimera.uchime. The Silva full length sequences and taxonomy references, consisting of 190,661 sequences (release 128), were used for taxonomy annotation42. To expedite taxonomy annotation, clustering was performed using pre.cluster by grouping reads that are within one mismatch of each other. Supplementary Table S1 shows the number of total reads and unique reads, prior to processing and post processing for each of the 16 specimens sequenced in this study.

Each read obtained from a 16S-23S rRNA sequencing run was subjected to taxonomy annotation after removing putative chimeric sequences and clustering. BLAST with NCBI nucleotide collection database was used to find the bacterial species with the best match for each read. When the best matched strain showed less than 90% identity or the length of the best matched strain was less than 25% of each read length, the read was labeled as unclassified.

Each specimen’s α diversity with the Shannon diversity index was measured using alpha_diversity.py in QIIME43. To calculate β diversity, all 16 specimens’ fasta files were combined as a single file. Closely related sequences with similarities greater than 97% were grouped as an operational taxonomic unit (OTU) using pick_otus.py in QIIME and each OTU’s representative sequence was picked using pick_rep_set.py. The selected representative sequences were aligned using align_seqs.py with the MUSCLE algorithm. Then the OTU table and phylogenetic tree were obtained using make_otu_table.py and make_phylogeny.py, respectively. Using QIIME jackknifed_beta_diversity.py, jackknife resampling was performed by sampling 1% of the total sequences and repeated 10 times to obtain specimen pair’s β diversity matrices and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots.

Permutation t test

We statistically examined differences in family or genus abundance between pre-PrEP and post-PrEP specimens. The standard t-tests for paired measurements assume independence, normality, and constant variance. With abundance proportions, it is likely that normality and constant variance are not held and the sample size is not large enough to use approximate normality of the mean. Instead, we conducted a permutation test in order to empirically assess the asymptotic p-values. The permutation test has been widely recommended in multiple statistical testing44–46. For each family or genus, a t-statistic was computed on the observed diversity data as follows:

| 1 |

where n is the number of participants, POSTav (PREav) is the average abundance of a given family or genus among post-PrEP (pre-PrEP) specimens, and POSTvar (PREvar) is the abundance variance of a given family or genus among post-PrEP (pre-PrEP) specimens. The PrEP status was then randomly permuted, holding the numbers of pre-PrEP and post-PrEP specimens constant over permutations; a total of 100,000 such permutations were completed. A t-statistic in Eq. (1) was computed for each permutation and the empirical p-value of each family or genus was calculated as the proportion of permutations with a t-test statistic greater than or equal to the t-test statistic derived from the actual data when the original t value was greater than zero. Otherwise, the empiric p-value was determined as the proportion of permutations with a t-test statistic less than or equal to the negative original t value. Based on this empirical p-value, the families or genera with significant differences in abundance between pre-PrEP and post-PrEP were determined. We also performed paired permutation tests for a given family or genus where we permuted each participant’s pre-PrEP and post-PrEP abundance values, yielding a total of 2n permutations. For each permutation, a t-statistic was measured and the empirical p-value was obtained from the proportion of permuted t-statistics that were more extreme than the observed data t-statistic.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI095066 and AI083115 (to HYL) and by EI-11-SD-005 from the California HIV/AIDS Research Program (to SRM). We thank the CCTG 595 study participants. We thank Sharon Chang and Kelli Brooks for providing help in sequencing and William DePaolo, Wendy Mack and Emily Johnson for helpful discussions. We thank the University of California, Los Angeles Technology Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics and RTL genomics.

Author Contributions

M.P.D., S.Y.P., H.R. and H.Y.L. designed the study, performed sequencing and conducted bioinformatics analyses. M.P.D. and S.R.M. chose the study cohort and complied clinical data of the study participants. S.Y.P., H.Y.L. and T.L. performed sequence analysis and statistical testing. All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All microbiome sequence data from this study are available at EBI with accession numbers PRJEB29018 and PRJEB29019.

Competing Interests

M.P.D. has served as a consultant to Gilead Sciences, Astra Zeneca and Theratechnologies, and has received research funding paid to his University from Gilead Sciences, ViiV, and Theratechnologies. All other authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-33524-6.

References

- 1.Rawlings, K. M. S. In International AIDS Conference (Durban, South Africa, 2016).

- 2.Grant RM, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gandhi M, et al. Association of age, baseline kidney function, and medication exposure with declines in creatinine clearance on pre-exposure prophylaxis: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e521–e528. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulligan K, et al. Effects of Emtricitabine/Tenofovir on Bone Mineral Density in HIV-Negative Persons in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:572–580. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tourret J, Deray G, Isnard-Bagnis C. Tenofovir Effect on the Kidneys of HIV-Infected Patients: A Double-Edged Sword? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1519–1527. doi: 10.1681/Asn.2012080857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stellbrink HJ, et al. Comparison of changes in bone density and turnover with abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine in HIV-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:963–972. doi: 10.1086/656417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohler JJ, et al. Tenofovir renal proximal tubular toxicity is regulated by OAT1 and MRP4 transporters. Lab Invest. 2011;91:852–858. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grigsby IF, et al. Tenofovir treatment of primary osteoblasts alters gene expression profiles: implications for bone mineral density loss. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;394:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casado JL, et al. Bone mineral density decline according to renal tubular dysfunction and phosphaturia in tenofovir-exposed HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2016;30:1423–1431. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong J, et al. Expansion of urease- and uricase-containing, indole- and p-cresol-forming and contraction of short-chain fatty acid-producing intestinal microbiota in ESRD. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39:230–237. doi: 10.1159/000360010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan J, et al. Gut microbiota induce IGF-1 and promote bone formation and growth. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E7554–E7563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607235113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YC, Greenbaum J, Shen H, Deng HW. Association Between Gut Microbiota and Bone Health: Potential Mechanisms and Prospective. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2017;102:3635–3646. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yocum RR, Rasmussen JR, Strominger JL. The mechanism of action of penicillin. Penicillin acylates the active site of Bacillus stearothermophilus D-alanine carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:3977–3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smieja M. Current indications for the use of clindamycin: A critical review. Can J Infect Dis. 1998;9:22–28. doi: 10.1155/1998/538090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tenson T, Lovmar M, Ehrenberg M. The mechanism of action of macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin B reveals the nascent peptide exit path in the ribosome. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;330:1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Waaij D. The ecology of the human intestine and its consequences for overgrowth by pathogens such as Clostridium difficile. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1989;43:69–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.43.100189.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falony G, et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science. 2016;352:560–564. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore, D. J. et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Daily Text Messages To Support Adherence to PrEP In At-Risk for HIV Individuals: The TAPIR Study. Clin Infect Dis 66, 1566–1572 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Huttenhower C, et al. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollister EB, Gao CX, Versalovic J. Compositional and Functional Features of the Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Their Effects on Human Health. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1449–1458. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armani RG, et al. Gut Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:29. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0727-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Xin, Jia Xiaoyue, Mo Longyi, Liu Chengcheng, Zheng Liwei, Yuan Quan, Zhou Xuedong. Intestinal microbiota: a potential target for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone Research. 2017;5:17046. doi: 10.1038/boneres.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook, L. C., LaSarre, B. & Federle, M. J. Interspecies Communication among Commensal and Pathogenic Streptococci. Mbio4, e00382–13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kaci G, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of Streptococcus salivarius, a commensal bacterium of the oral cavity and digestive tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:928–934. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03133-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Roos NM, Katan MB. Effects of probiotic bacteria on diarrhea, lipid metabolism, and carcinogenesis: a review of papers published between 1988 and 1998. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:405–411. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan, K. J. et al. Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. 286–8 (2004).

- 27.Reichmann P, et al. Genome of Streptococcus oralis strain Uo5. Journal of bacteriology. 2011;193:2888–2889. doi: 10.1128/JB.00321-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinumaki A, et al. Characterization of the gut microbiota of Kawasaki disease patients by metagenomic analysis. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:824. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van der Elst EM, et al. High Acceptability of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis but Challenges in Adherence and Use: Qualitative Insights from a Phase I Trial of Intermittent and Daily PrEP in At-Risk Populations in Kenya. Aids and Behavior. 2013;17:2162–2172. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0317-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mugwanya KK, Baeten JM. Safety of oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-based pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:265–273. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2016.1128412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glidden DV, et al. Symptoms, Side Effects and Adherence in the iPrEx Open-Label Extension. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1172–1177. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Araujo-Perez F, et al. Differences in microbial signatures between rectal mucosal biopsies and rectal swabs. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:530–535. doi: 10.4161/gmic.22157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanshew AS, Jette ME, Tadayon S, Thibeault SL. A comparison of sampling methods for examining the laryngeal microbiome. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaakoush, N. O. Insights into the Role of Erysipelotrichaceae in the Human Host. Front Cell Infect Micro5, 84 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Chen Weiguang, Liu Fanlong, Ling Zongxin, Tong Xiaojuan, Xiang Charlie. Human Intestinal Lumen and Mucosa-Associated Microbiota in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zackular, J. P. et al. The Gut Microbiome Modulates Colon Tumorigenesis. Mbio4, e00692–13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Zhang H, et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2365–2370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duda-Chodak A, Tarko T, Satora P, Sroka P. Interaction of dietary compounds, especially polyphenols, with the intestinal microbiota: a review. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:325–341. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0852-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brahe LK, et al. Specific gut microbiota features and metabolic markers in postmenopausal women with obesity. Nutr Diabetes. 2015;5:e159. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2015.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castillo-Mancilla JR, et al. Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:384–390. doi: 10.1089/AID.2012.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schloss PD, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quast C, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camargo A, Azuaje F, Wang H, Zheng H. Permutation - based statistical tests for multiple hypotheses. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dudoit S, Shaffer JP, Boldrick JC. Multiple hypothesis testing in microarray experiments. Stat Sci. 2003;18:71–103. doi: 10.1214/ss/1056397487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakagawa S. A farewell to Bonferroni: the problems of low statistical power and publication bias. Behav Ecol. 2004;15:1044–1045. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arh107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All microbiome sequence data from this study are available at EBI with accession numbers PRJEB29018 and PRJEB29019.