Summary

While in vitro liver tissue engineering has been increasingly studied during the last several years, presently engineered liver tissues lack the bile duct system. The lack of bile drainage not only hinders essential digestive functions of the liver, but also leads to accumulation of bile that is toxic to hepatocytes and known to cause liver cirrhosis. Clearly, bile duct tissue generation is essential for engineering functional and healthy liver. Differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to bile duct tissue requires long and/or complex culture conditions, and has been inefficient so far. Towards generating a fully functional liver containing biliary system, we have developed defined and controlled conditions for efficient 2D and 3D bile duct epithelial tissue generation. A marker for multipotent liver progenitor in both adult human liver and ductal plate in human fetal liver, EpCAM, is highly expressed in hepatic spheroids generated from human iPSCs. The EpCAM high hepatic spheroids can, not only efficiently generate a monolayer of biliary epithelial cells, in a 2D differentiation condition, but also form functional ductal structures in a 3D condition. Importantly, this EpCAM high spheroid based biliary tissue generation is significantly faster than other existing methods and does not require cell sorting. In addition, we show that a knock-in CK7 reporter human iPSC line generated by CRIPSR/Cas9 genome editing technology greatly facilitates the analysis of biliary differentiation. This new ductal differentiation method will provide a more efficient method of obtaining bile duct cells and tissues, which may facilitate engineering of complete and functional liver tissue in the future.

Keywords: Induced pluripotent stem cells, ductal differentiation, liver progenitor, 3D tissue engineering, spheroids

1. Introduction

Cholangiocytes are the ductal epithelial cells coating bile duct system in liver, which collect and deliver bile to the gallbladder or small intestine [1]. During liver development and in post-natal livers, ductal epithelial cells have been believed to be differentiated from hepatoblasts or bi-potent liver progenitor cells, which give rise to both hepatocytes and ductal cells [2,3]. These bi-potent progenitors have been reported to express some cholangiocytes markers [4,5]. Even though cholangiocytes comprise only a small proportion (3 to 5%) of liver cells [6], they play vital roles in a variety of liver diseases, including primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, liver cancer and alcoholic liver disease[7]. Over the recent several years, there has been significant improvement in generation of functional hepatocytes from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [8–10], to establish highly human relevant liver disease models. However, it is still challenging to efficiently generate biliary epithelial cells/tissues from human stem cells, preventing human iPSC based disease modeling and pathogenesis study of many biliary diseases. Here, we report efficient generation of biliary cells and structures in a controlled manner from human pluripotent stem cells. A bipotent liver progenitor marker, EpCAM [11–13], is highly expressed in hepatic spheroids derived from human iPSCs (Fig 1, 2, and 4). The EpCAM high hepatic spheroids could efficiently generate a monolayer of biliary epithelial cells, in a 2D differentiation condition (Fig 2, 4), and could form functional ductal structures in a 3D differentiation condition (Fig 3, 4). Importantly, this biliary tissue generation can be performed not only in a simple and controlled manner, but also with a high efficiency and speed compared to other existing methods [14–16]. This human stem cell based biliary differentiation method will provide a better resource for biliary/liver disease modeling and allow more complete and functional liver tissue engineering in the future.

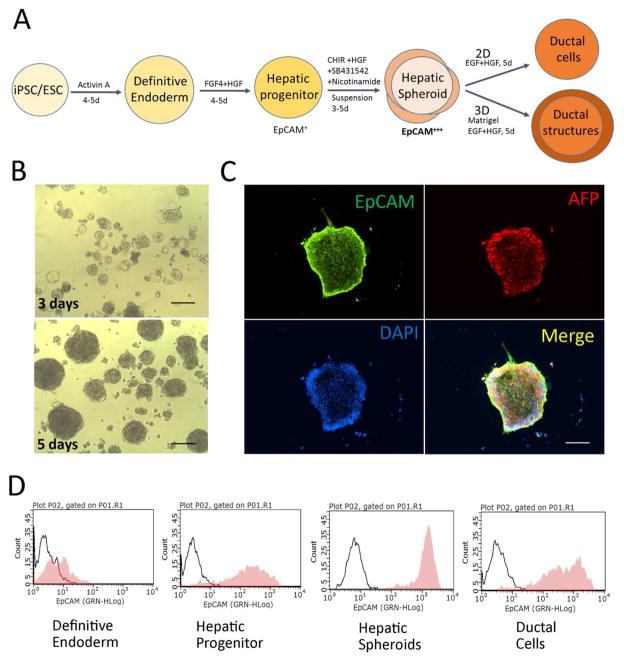

Figure 1. Generation of EpCAMhigh hepatic spheroids from human PSCs.

(A) A schematic diagram of ductal differentiation procedure. (B) Human iPSC derived hepatic spheroids. The human iPSC were differentiated into definitive endoderm (DE) and hepatic progenitor (HP) stage cells, and were subsequently cultured in a low-attachment culture dish for 3 to 5 days with CHIR99021, SB431542 and nicotinamide to support hepatic spheroid formation. (C, D) These hepatic spheroids expressed significantly higher levels of EpCAM, a bipotent liver progenitor marker, compared to other differentiation stages, by both protein and gene analyses (see Fig 2). The hepatic spheroids also expressed AFP, a hepatoblast marker. (D) Flow cytometric analysis shows the hepatic spheroids are enriched with exclusively EpCAM high cells. Scale Bar, 100μm

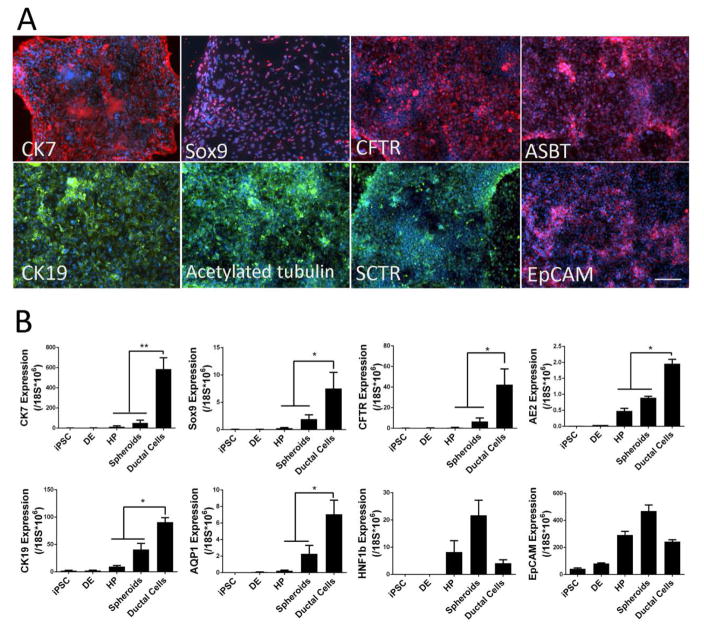

Figure 2. Generation of ductal epithelial cells in a 2D culture condition.

(A) Immunofluorescence analyses of bile duct epithelial cells in a 2D differentiation culture of human iPSC-derived hepatic spheroids. When the hepatic spheroids were further attached to a regular cell culture dish for 5 or more days in EGF containing media, they were induced into monolayers of biliary epithelial cells with high (over 90%) efficiency. These cells expressed multiple bile duct cell markers. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of ductal cell marker genes and genes associated with ductal cell commitment, for each stage of ductal differentiation from undifferentiated human iPSCs. These data suggest that the human iPSC-derived hepatic spheroids efficiently differentiate into bile ductal epithelial cells in a defined 2D differentiation condition. DE: definitive endoderm cells derived from human iPSC/ESC, HP: hepatic progenitor cells derived from human iPSC/ESC, Scale Bar, 100μm. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01.

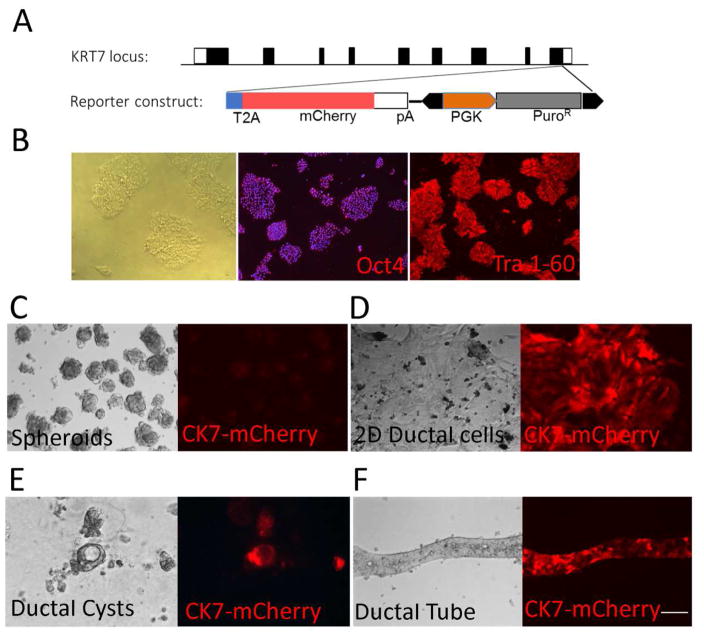

Figure 4. Ductal differentiation using a CK7-mCherry reporter human iPSC line.

(A, B) To efficiently determine the kinetics of ductal tissue generation, we have generated a reporter human iPSC line, which is designed to express a ductal marker, CK7, when properly differentiated. The genomic locus of KRT7 (CK7) gene and the reporter construct are shown (A). Using CRISPR/Cas9 system, the mCherry reporter cassette and the puromycin-resistance cassette were inserted at the end of CK7 coding sequence to replace the endogenous “TGA” stop codon in exon 9. A T2A self-cleaving peptide was inserted between CK7 and mCherry. The PGK-Puro selection cassette, flanked by a piggyBac inverted terminal repeat sequences, was removed by transient expression of piggyBac transposase in the iPSC line with targeted integration. This reporter line can express pluripotency markers, including Oct4 and Tra 1–60, before differentiation (B). (C) This CK7 reporter line formed hepatic spheroids based on our ductal differentiation method, (D) expressed cherry signal in the 2D differentiation condition, and (E, F) formed cherry positive ductal cysts and tubes in the 3D culture condition. The time frame for each stage differentiation of this reporter iPSC was consistent with control iPSCs (Fig 1A). These data not only confirm our 2D/3D ductal differentiation protocols but also provide a great resource for kinetic or imaging studies of human bile duct development. Scale Bar, 100μm

Figure 3. Ductal structure formation in a 3D culture condition.

(A, B) Ductal structure formation in a Matrigel based 3D culture. To recapitulate the epithelial polarity of bile duct cells in vivo and ductal structure formation, we cultured human iPSC-derived hepatic spheroids in a 3D differentiation condition containing thick Matrigel and EGF/HGF. Within 5 to 10 days in 3D condition, ductal cells formed round cysts with a central luminal space enclosed by a monolayer of cells as well as bile duct-like tubular structures expressing ductal marker proteins. (C) Secretory function of 3D ductal cysts. To determine the secretory function of differentiated 3D ductal structures, we incubated the ductal cysts with rhodamine123, which can be secreted into the luminal space by MDR, an ATP-dependent transmembrane export pump. The fluorescence intensity inside of the ductal cysts was much higher than the surroundings, which demonstrated that rhodamine123 was successfully transported into luminal space by ductal cells. In addition, this effect can be inhibited by verapamil, an MDR inhibitor. These data demonstrate that the iPSC-derived ductal structures in a 3D condition resemble characteristics and functionality of bile duct tissue in vivo. Scale Bar, 100μm

2. Materials

This study was performed in accordance with the Johns Hopkins Intuitional Stem Cell Research Oversight regulations and followed approved protocols by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

2.1 Human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines

The human iPSC lines used in this study were previously generated from diverse healthy donor tissues [17–19]. To further investigate the ductal cells differentiation process, we generated a CK7-mCherry reporter iPSC line by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination (Figure 4). All these iPSC lines are cultured in a feeder free condition (mTeSR1 medium and Matrigel coated plates).

2.2 Human iPSC culture reagents

Matrigel hESC qualified Matrix (BD Biosciences, Cat. No. 354277), store at −20°C

Human iPSC culture medium: mTeSR1 medium kit (Stemcell Technologies, Cat.No.05850)

DMEM/F12 medium (Corning, Cat. No.10-092-CV), store at 4°C

Collagenase Type IV (Sigma, Cat.No.C5138-5g), store at 4°C. Prepare 1mg/ml collagenase IV solution with DMEM/F12 and filter for sterilization. Store the collagenase solution at 4°C

Accutase solution (Sigma, Cat. No. A6964-100ml), store at −20°C

Cell Scraper 25cm (Sarstedt, Cat. No. 83.1830)

Y-27632 dihydrochloride (a ROCK inhibitor; Tocris Bioscience, Cat. No. 1254-50mg). Make 20μl stock aliquots of 100mM in PBS and store at −20°C. For use in experiments, thaw the frozen aliquot, dilute the 20μl in 380μl PBS to yield a 5mM solution and store at 4°C. The desired final concentration to treat cells is 2–10μM.

Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco, Cat. No. 15140-122), store at −20°C

CryoStem Freezing Medium (Stemgent, Cat. No. 01-0013-50), store at 4°C

Tissue-culture treated 12 well plastic plates (Thermo Scientific, Cat. No. 130185)

2.3 Ductal Differentiation reagents

RPMI 1640 Medium with GlutaMAX (Gibco, Cat.No. 61870-036), store at 4°C

Recombinant human Activin A (R&D systems, Cat. No. 338-AC/CF). Make 25μl stock aliquots of 1mg/ml in PBS and store at −80°C. For use in experiments, thaw the frozen aliquot, dilute the 25μl in 225μl RPMI1640 medium to yield a 100μg/ml solution and store at 4°C. The desired concentration to treat cells is 50–100 ng/ml.

B27 supplement (Gibco, Cat. No. 17504-044), aliquot and store at −20°C.

CHIR 99021 (Tocris, Cat. No. 4423, GSK-3 inhibitor). Make 250μl stock aliquots of 20mM in DMSO and store at −20°C. For use in experiments, thaw the frozen aliquot, dilute the 250μl in 250μl DMSO to yield a 10mM solution and store at 4°C. The desired final concentration to treat cells is 1–2μM.

Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS) (Corning Cellgro, Cat. No. 25-800-CR), store at 4°C. This solution contains 1000 mg/L human recombinant insulin, 550mg/L human recombinant transferrin and 0.67 mg/L selenious acid.

GlutaMax Supplement (Gibco, Cat. No. 35050-061), store at 4°C.

SB431542 (Cayman, Cat. No.301836-41-9). Make stock aliquots of 50mM in DMSO and store at −20°C. The final working concentration is 5μM.

Nicotinamide (Stemcell Technologies, Cat. No. 07154). Make 5M solution in PBS and store at 4°C. The final working concentration is 5mM.

Gentamicin solution (Sigma, Cat. No. G1397-10ml), store at 4°C.

Recombinant human FGF-4 (R&D systems, Cat. No. 235-F4/CF). Make 50μl stock aliquots of 500μg/ml in PBS and store at −80°C. For use in experiments, thaw the frozen aliquot, dilute the 50μl in 200μl PBS to yield a 100μg/ml solution and store at −20°C. The desired concentration to treat cells is 10 ng/ml.

Recombinant human HGF (R&D systems, Cat. No. 294-HG/CF). Make 50μl stock aliquots of 500μg/ml in PBS and store at −80°C. For use in experiments, thaw the frozen aliquot, dilute the 50μl in 200μl PBS to yield a 100μg/ml solution and store at −20°C. The desired concentration to treat cells is 10 ng/ml.

Recombinant human EGF (R&D systems, Cat. No.236-EG-01M). Make 50μl stock aliquots of 500μg/ml in PBS and store at −80°C. For use in experiments, thaw the frozen aliquot, dilute the 50μl in 200μl PBS to yield a 100μg/ml solution and store at −20°C. The desired concentration to treat cells is 20 ng/ml.

Hepatic Spheroid Culture Medium (HSCM): The HSCM contains 15mM of HEPES, 1% of ITS solution, 0.5% of B27, 2μM of CHIR99021, 5μM of SB431542, 5mM of nicotinamide, and 0.1% of Gentamicin in RPMI. Filter this base medium and store at 4°C. Prior to use in cell culture, supplement this medium with HGF at final concentration of 10ng/ml.

Biliary differentiation medium (BDM): The base BDM contains 15mM of HEPES, 1% of ITS solution, 0.5% of B25, and 0.1% gentamicin in RPMI. Filter this base medium and store at 4°C. Prior to use in cell culture, supplement this medium with 10ng/ml HGF and 20ng/ml EGF at final concentration.

Ultra-low attachment 6 well plates (Corning, Cat. No. 3471)

2.4 Antibodies used in the study

Primary antibodies against AFP (1:200, Dako, A0008), EpCAM (1:200, R&D Systems, AF960), CK7(1:200, Millipore, mab3554), CK19(1:200, Santa Cruz, sc-6278), CFTR (1:200,Abcam, ab2784), SCTR (1:50, Santa Cruz, sc-26633), ASBT (1:50, Santa Cruz, sc-27493), Acetyl-a-tubulin (1:500, Sigma, t7451), Sox9 (1:150, R&D Systems, AF3075), Oct4 (1:200, Millipore, mab4401), Tra 1–60 (1:200, Millipore, mab4360).

2.5 Other reagents and kits

TRIzol Reagent (Ambion, Cat # 15596018)

High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Cat. No. 4368813)

StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Cat # 4371435).

TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (2X) (Applied Biosystems, Cat # 4367846). Store at 4°C, thaw to room temperature as required.

TaqMan gene expression assay reagent for 18S rRNA (Hs03003631_g1), EpCAM (Hs00901885_m1), HNF1b (Hs01001602_m1), AE2 (Hs01586776_m1), AQP1 (Hs01028916_m1), CK7 (Hs00559840_m1), CK19 (Hs00761767_s1), Sox9 (Hs01001343_g1), CFTR (Hs01565537_m1).Store at −20°C, thaw on ice when required.

Guava easyCyte Flow Cytometer (Millipore)

Rhodamine 123 (Cayman, Cat.No.16672)

Verapamil (Cayman, Cat.No. 14288)

3. Methods

3.1 Matrigel coating of 12 well plates for pluripotent stem cell culture

The whole procedure should be performed under extra aseptic condition.

Thaw frozen Matrigel overnight at 4 °C. Prepare 1:4 dilution of Matrigel with chilled DMEM/F12. Prepare 5ml aliquots using chilled pipettes and freeze them at −20°C.

Thaw one 5ml aliquot on ice.

Transfer the thawed aliquot to cold 500 ml DMEM/F-12 medium, mix well and keep on ice.

Add 1ml/well diluted Matrigel into 12 well plates using chilled pipettes. Wrap the coated plates using aluminum foil and incubate at room temperature for 1 hour. Store in 4 °C (see Note 1).

When the plate is ready for iPSC culture, bring the plate to room temperature.

Remove the Matrigel solution. Ensure that the coated surface is not scratched by pipette.

Immediately add 0.5ml/well iPSC culture medium and then plate cells.

3.2 Human iPSC culture and hepatic spheroid formation

3.2.1 Human iPSC culture

Thaw iPSCs lines onto Matrigel coated 12 well plates (see Note 2). Culture the cells in mTeSR1 medium at 37°C with 5% CO2. Observe the morphology of the colonies under the microscope and change medium every day. When the colonies are large and ready to merge, passage the cells with Accutase or Collagenase IV (see Note 3).

3.2.2

Differentiation of human iPSCs to EpCAM high hepatic spheroids (Figure 1). It is important that the iPSC colonies be evenly distributed and reach 50–80% confluence before starting differentiation. Prior to induction of spheroids formation, the human iPSC/ESCs were differentiated into definitive endoderm and hepatic stem/progenitor cells as previously described [10,17–22].

Day 0: Replace iPSC culture medium with warm RPMI medium supplemented with 50–100 ng/ml Activin A and 1–2μM CHIR99021 (see Note 4). Incubate the cells at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Day 1–4/5: Continue replacing the previous culture medium with fresh RPMI supplemented with 50–100ng/ml Activin A and 0.05–2% B27 daily (see Note 5). After day 4, more than 90% of the cells express definitive endoderm (DE) markers like Sox17 and CXCR4.

Day 4–9/10: Change medium to RPMI supplemented with 0.1–1% B27, 10ng/ml HGF and 10ng/ml FGF-4 every day. Following HGF/FGF-4 treatment, majority of cells express low degree of EpCAM, a multipotent hepatic progenitor marker (Figure 1A, D).

Day 9/10–13/15: Dissociate the d9/10 hepatic progenitor cells with Accutase and replate them in a low-attachment culture dish. Change medium to HSCM supplemented with 10ng/ml HGF. Within 3~5 days in the low-attachment dish, the hepatic progenitors in suspension culture form hepatic spheroids (Figure 1B). At culture day 13–15, over 90% of hepatic spheroids express high level of EpCAM (Figure 1D).

3.3 Ductal differentiation in defined 2D and 3D conditions

3.3.1 Cholangiocyte differentiation in a 2D condition

Approximately 3 to 5 days after suspension culture of hepatic spheroids (3.2.2), replate the spheroids in a regular cell culture dish to induce attachment as a monolayer (see Note 6). Change medium to BDM containing 20 ng/ml EGF and 10 ng/ml HGF [23].

Continue culturing in the BDM for 5 days. By day 18 to 20, over 90% of the adherent cells express multiple cholangiocyte markers, including CK7, CK19, SOX9, SCTR, ASBT, AE2, AQP1 and Acetyl-alpha-tubulin as well as cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a mature and functional cholangiocyte marker [24] (Figure 2). To analyze the expression of biliary epithelial cell specific genes and proteins, harvest the cells for real-time PCR, flow cytometry and perform immune-staining in culture dish (step 3.4).

3.3.2 Ductal structure formation in 3D conditions

To induce functional ductal structures such as ductal cysts and tubes, hepatic spheroids can be cultured in thick Matrigel.

Dissociate the human iPSC-derived EpCAM high hepatic spheroids (3.2.2) carefully with Accutase (see Note 7), and then suspend in 1:4 diluted Matrigel (25% Matrigel in DMEM/F12) at density of 5×104 cells/ml. Place the gel in 37°C for 1~2 hours for solidification.

Culture the cells in 3D gels in EGF and HGF containing BDM for 5 to 10 days to form ductal structures (Figure 3A, B). By day 20, the replated cells in thick Matrigel will form ductal cysts which express multiple ductal cell markers and transport function of bile ducts (Figure 3C).

3.4 Assessment of ductal markers and functionality in human iPSC-derived mature ductal tissue

For Real-time PCR, collect total RNA using TRIzol. Measure the RNA concentration and proceed for cDNA synthesis using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit. Set-up 10–20ul reaction for each well in a 96 well plate using TaqMan Gene Expression assays. Run Real-time PCR using StepOnePlus system.

Immunofluorescence: Fix cells or tissues with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Add primary antibodies diluted in PBS with 3% BSA and 0.15% Triton X-100 to cells/tissues. Incubate the cells with appropriate primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, and with Alexa Flour 594 or 488 secondary antibodies at room temperature for 30 min. Counterstain with DAPI. Record images.

Flow cytometric analysis: Dissociate cells by 0.05% trypsin. Incubate the dissociated single cells with EpCAM antibody for 30 min at 4°C. Wash the cells twice with PBS containing 0.01% BSA, then incubate them with Alexa Flour 488 labeled secondary antibody for 30 min at 4°C. After washing twice, resuspend the cells in PBS. Perform analysis with a Flow Cytometer.

Rhodamine123 transport assay: Incubate the ductal structures with RPMI media containing 50 μM rhodamine123 for 10 min at 37 degree and then wash thrice with RPMI media before imaging. To confirm that the transport of rhodamine123 depends on MultiDrug Resistance (MDR) protein activity, 5μM verapamil (Cayman), a MDR inhibitor, was added 30 min before rhodamine treatment. The images were taken with using a Nikon microscope.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from Maryland Stem Cell Research Funds (2013-MSCRFII-0170 and 2014-MSCRFF-0655) and by NIH (P30DK089502).

Footnotes

Use the cell culture plates within one week of coating with Matrigel. The plates should not be used for human iPSC culture, if not fully coated.

Freeze cells from 6 wells of a 12 well plate (approximately 2 to 4 million cells) in 1 freezing vial with CryoStem Freezing medium. When thawing, thaw the cells from one freezing vial into an entire 12 well plate. Do not start the hepatic differentiation right after thawing the iPSCs when the cells are still quiescent.

Pass the colonies as small cell aggregates. The split ratio varies with the growth condition of different cell lines (1:2–1:5). Y-27632 at 2–10 μM can be added to the culture medium to increase cell viability.

There is difference in terms of ingredients among RPMI 1640 medium from different suppliers. The RPMI 1640 medium from Gibco works better for endoderm differentiation of most of the iPSC lines tested by us.

Observe the cells under the microscope every day, and then determine an optimum concentration of B27 (0.02–2%) based upon cell viability and differentiation status. Ideally, there should be cells with uniform DE morphology attached to the plate and less than 5% of dead cells floating in the medium. When cell viability is compromised, increase B27 concentration to protect the cells. It is essential to keep an even distribution of the cells in the plates in order to obtain the best DE differentiation efficiency (>99%).

Adding thin matrigel coating may increase viability of cells in 2D biliary differentiation condition.

To increase cells viability, hepatic spheroids can be attached to regular culture plate 1 day before dissociation. Add 5μM Y-27632 to BDM on first 1~2 days of 3D culture.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tietz PS, Larusso NF. Cholangiocyte biology. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22(3):279–287. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000218965.78558.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strazzabosco M, Fabris L. Development of the bile ducts: essentials for the clinical hepatologist. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1159–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gouw AS, Clouston AD, Theise ND. Ductular reactions in human liver: diversity at the interface. Hepatology. 2011;54(5):1853–1863. doi: 10.1002/hep.24613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okabe M, Tsukahara Y, Tanaka M, Suzuki K, Saito S, Kamiya Y, Tsujimura T, Nakamura K, Miyajima A. Potential hepatic stem cells reside in EpCAM+ cells of normal and injured mouse liver. Development. 2009;136(11):1951–1960. doi: 10.1242/dev.031369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanimizu N, Mitaka T. Re-evaluation of liver stem/progenitor cells. Organogenesis. 2014;10(2):208–215. doi: 10.4161/org.27591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SJ, Park JB, Kim KH, Lee WR, Kim JY, An HJ, Park KK. Immunohistochemical study for the origin of ductular reaction in chronic liver disease. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(7):4076–4085. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazaridis KN, LaRusso NF. The Cholangiopathies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(6):791–800. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takayama K, Inamura M, Kawabata K, Katayama K, Higuchi M, Tashiro K, Nonaka A, Sakurai F, Hayakawa T, Furue MK, Mizuguchi H. Efficient generation of functional hepatocytes from human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells by HNF4alpha transduction. Mol Ther. 2012;20(1):127–137. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma X, Duan Y, Tschudy-Seney B, Roll G, Behbahan IS, Ahuja TP, Tolstikov V, Wang C, McGee J, Khoobyari S, Nolta JA, Willenbring H, Zern MA. Highly efficient differentiation of functional hepatocytes from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2(6):409–419. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi SM, Kim Y, Liu H, Chaudhari P, Ye Z, Jang YY. Liver engraftment potential of hepatic cells derived from patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(15):2423–2427. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huch M, Gehart H, van Boxtel R, Hamer K, Blokzijl F, Verstegen MM, Ellis E, van Wenum M, Fuchs SA, de Ligt J, van de Wetering M, Sasaki N, Boers SJ, Kemperman H, de Jonge J, Ijzermans JN, Nieuwenhuis EE, Hoekstra R, Strom S, Vries RR, van der Laan LJ, Cuppen E, Clevers H. Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huch M, Dorrell C, Boj SF, van Es JH, Li VS, van de Wetering M, Sato T, Hamer K, Sasaki N, Finegold MJ, Haft A, Vries RG, Grompe M, Clevers H. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494(7436):247–250. doi: 10.1038/nature11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause P, Unthan-Fechner K, Probst I, Koenig S. Cultured hepatocytes adopt progenitor characteristics and display bipotent capacity to repopulate the liver. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(7):805–817. doi: 10.3727/096368913X664856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogawa M, Ogawa S, Bear CE, Ahmadi S, Chin S, Li B, Grompe M, Keller G, Kamath BM, Ghanekar A. Directed differentiation of cholangiocytes from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(8):853–861. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dianat N, Dubois-Pot-Schneider H, Steichen C, Desterke C, Leclerc P, Raveux A, Combettes L, Weber A, Corlu A, Dubart-Kupperschmitt A. Generation of functional cholangiocyte-like cells from human pluripotent stem cells and HepaRG cells. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):700–714. doi: 10.1002/hep.27165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampaziotis F, Cardoso de Brito M, Madrigal P, Bertero A, Saeb-Parsy K, Soares FA, Schrumpf E, Melum E, Karlsen TH, Bradley JA, Gelson WT, Davies S, Baker A, Kaser A, Alexander GJ, Hannan NR, Vallier L. Cholangiocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for disease modeling and drug validation. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(8):845–852. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi SM, Liu H, Chaudhari P, Kim Y, Cheng L, Feng J, Sharkis S, Ye Z, Jang YY. Reprogramming of EBV-immortalized B-lymphocyte cell lines into induced pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2011;118(7):1801–1805. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-340620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H, Kim Y, Sharkis S, Marchionni L, Jang YY. In vivo liver regeneration potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells from diverse origins. Science translational medicine. 2011;3(82):82ra39. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Ye Z, Kim Y, Sharkis S, Jang YY. Generation of endoderm-derived human induced pluripotent stem cells from primary hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2010;51(5):1810–1819. doi: 10.1002/hep.23626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian L, Prasad N, Jang YY. In Vitro Modeling of Alcohol-Induced Liver Injury Using Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/7651_2014_168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SM, Kim Y, Shim JS, Park JT, Wang RH, Leach SD, Liu JO, Deng C, Ye Z, Jang YY. Efficient drug screening and gene correction for treating liver disease using patient-specific stem cells. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2458–2468. doi: 10.1002/hep.26237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chun YS, Chaudhari P, Jang YY. Applications of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells; focused on disease modeling, drug screening and therapeutic potentials for liver disease. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6(7):796–805. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanimizu N, Miyajima A, Mostov KE. Liver progenitor cells develop cholangiocyte-type epithelial polarity in three-dimensional culture. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(4):1472–1479. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueno Y, Alpini G, Yahagi K, Kanno N, Moritoki Y, Fukushima K, Glaser S, LeSage G, Shimosegawa T. Evaluation of differential gene expression by microarray analysis in small and large cholangiocytes isolated from normal mice. Liver Int. 2003;23(6):449–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2003.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]