Abstract

One of the defining features of animals is their ability to navigate their environment. Using behavioral experiments this topic has been under intense investigation for nearly a century. In insects, this work has largely focused on the remarkable homing abilities of ants and bees. More recently, the neural basis of navigation shifted into the focus of attention. Starting with revealing the neurons that process the sensory signals used for navigation, in particular polarized skylight, migratory locusts became the key species for delineating navigation-relevant regions of the insect brain. Over the last years, this work was used as a basis for research in the fruit fly Drosophila and extraordinary progress has been made in illuminating the neural underpinnings of navigational processes. With increasingly detailed understanding of navigation circuits, we can begin to ask whether there is a fundamentally shared concept underlying all navigation behavior across insects. This review highlights recent advances and puts them into the context of the behavioral work on ants and bees, as well as the circuits involved in polarized-light processing. A region of the insect brain called the central complex emerges as the common substrate for guiding navigation and its highly organized neuroarchitecture provides a framework for future investigations potentially suited to explain all insect navigation behavior at the level of identified neurons.

Introduction

Animals navigate their surroundings to find food, to avoid being eaten, to find reproductive partners, and to escape unfavorable environmental conditions. In order to do this, all animals, including insects, have to select a goal and establish where they currently are in relation to that goal by using appropriate sensory information (Figure 1). Navigational goals can either be physical locations or goal directions and are continued to be actively pursued after disturbance, a feature not present in directional escape reflexes. Independent of which strategy an animal uses to pursue a navigational goal, it has to continuously compare its current heading (body orientation) with its desired heading (goal-direction) and translate any mismatch into compensatory steering commands (Figure 2). The brain has to extract relevant information from the continuous stream of diverse, navigation relevant sensory signals and eventually use it to initiate steering. This task is not trivial even in seemingly simple animals, as in each moment in time the animal’s intended heading will be additionally defined by behavioral and motivational state and by previous experience, which together provide the context for adequate behavioral decisions that amount to a coherent navigational strategy [1–3].

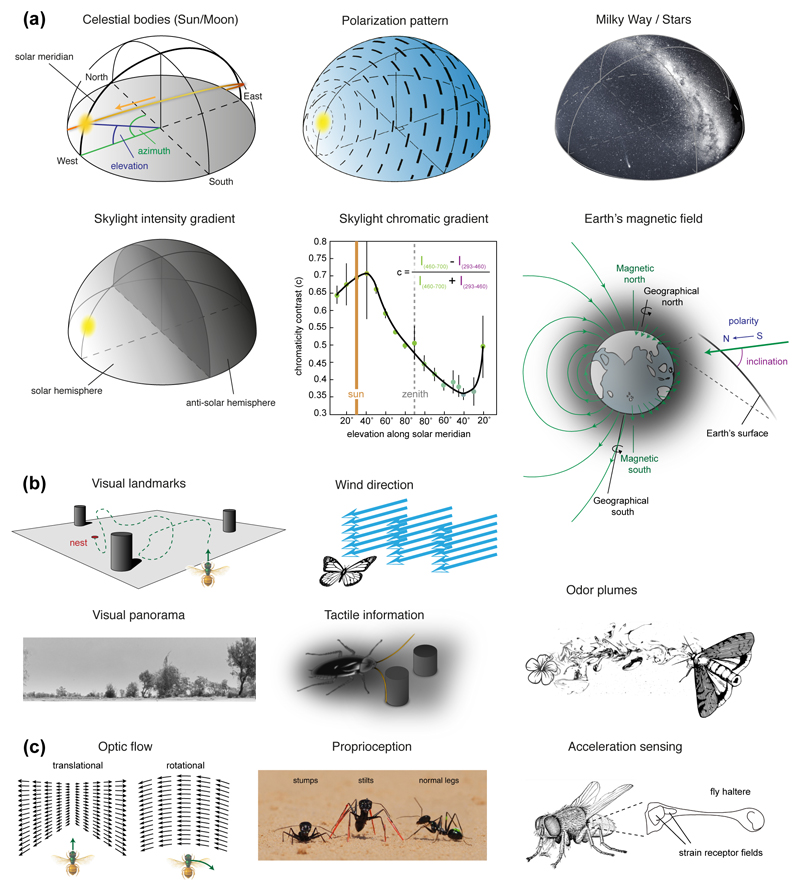

Figure 1. Sensory information used for insect navigation.

(a) Global external cues. Polarization pattern, intensity- and chromatic gradient result from scattering of direct sunlight (or moon-light) in the upper atmosphere. They are most prominent during the day, but their much dimmer nocturnal versions can also be used for navigation by night-active insects. The chromatic gradient in the sky results from a higher proportion of green light in the solar hemisphere (curve from [14]). The Earth’s magnetic field offers three main cues for navigation, the inclination of the field lines, their polarity, as well as the intensity of the field (not shown). The Milky Way is used for straight-line navigation by dung beetles [66,67]. (b) Local external cues. Visual panorama from [68]. Wind has been shown to play a role in moths [69] and ants [70]. Tactile cues perceived through the antenna provide major information to nocturnal cockroaches and are encoded by neurons in the central complex [71]. Odor plumes are key for pheromone following behavior in moths [64] but are also important for, e.g., ant navigation [72]. (c) Internal cues (idiothetic cues). Translational and rotational optic flow in response to self-motion provides information about forward velocity and angular velocity of an animal. Proprioception is essential for instance in Cataglyphis ants that use a step counting mechanism as basis for their odometer during path integration [41]. The photograph depicts ants with manipulated leg lengths during experiments that revealed the step counting mechanism [41] (photo curtesy of Matthias Wittlinger). Acceleration sensing provides information about body rotations at high temporal precision and is best understood in the fly haltere system [73].

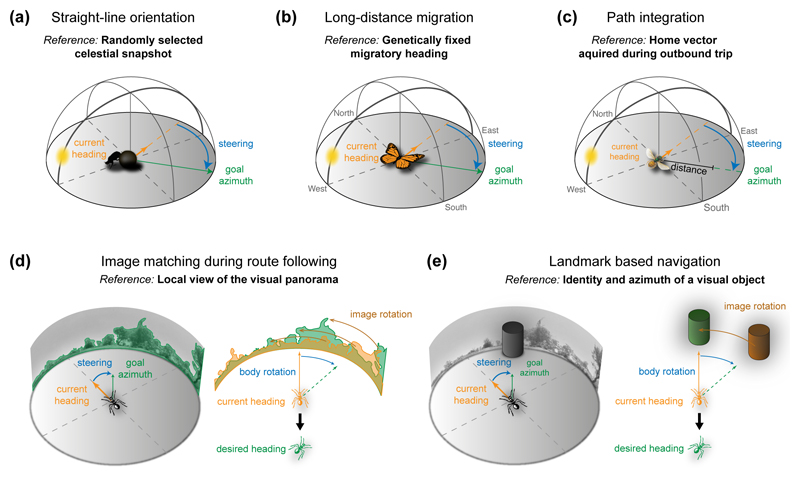

Figure 2. Goal-directions during different navigational strategies of insects.

(a) Straight-line orientation, performed by ball-rolling dung beetles, uses a randomly selected celestial snapshot as reference for the goal direction [45]. If disturbed, the new body orientation (orange) is realigned with the goal direction (green) by performing a rotational ‘dance’ on the dung ball [45]. (b) Long distance migration, performed by e.g. Monarch butterflies [48], the desert locust [74] and the Bogong moth [47], is similar to straight-line orientation, except for using a genetically fixed goal direction within a constant, global reference frame. (c) Path integration, performed by e.g. ants [1] and bees [37], uses a goal direction obtained by integrating speed- and direction-changes during the outbound foraging trip. This home-vector points straight back to the nest and, during homing, is compared against the current heading within the same reference frame (often: global sky-based reference frame). (d) Image matching, as performed by ants in rich visual environments [75], is used for following habitual routes between a food source and the nest. A series of snapshots of the visual panorama are compared to current views of the panorama and both are brought to a best match by performing body rotations [2]. (e) Landmark based navigation uses salient visual features independent of the surrounding panorama in a similar way to overall image matching. Landmarks are also used during route following [3] and have been proposed to be combined with vectors to form internal maps [76]. Note that individual navigation strategies rarely operate in isolation and at any given moment in time the goal direction of the animal can be the result of integrating multiple navigational subsystems (e.g. [34]).

Overall, three neural processes are required for navigation and will be covered by this review: First, representation of the animal’s current heading; second, representation of the animal’s desired heading; and third, comparing both to generate steering commands.

Neural correlates of an insect’s current heading

The first insights into brain circuits underlying navigation resulted from illuminating neural responses to polarized light. Polarized skylight is a visual compass cue that allows animals to infer the sun’s azimuth when viewing a small patch of blue sky (Figure 1a). Thus, neurons tuned to specific polarized-light angles (POL-neurons) likely mediate navigation-relevant signals about body orientation with respect to a global, sky-based reference frame. After POL-neurons had been identified in the optic lobes of crickets and locusts [4–7], a pathway to the central complex (CX), a group of neuropils in the center of the insect brain [8–10], was characterized (reviewed in [11,12]). Along this pathway, polarized-light information is integrated with other skylight derived directional cues (Figure 1a) into a coherent compass signal [6,13–16]. The CX then contains a multitude of POL-neurons in locusts [12], butterflies [16], beetles [17], and bees [18] (Figure 3a). They define a neural network proposed to transform purely sensory compass signals into premotor commands suited to guide navigation [11,19]. Importantly, in the protocerebral bridge (PB) (one CX-compartment) each POL-neuron’s tuning correlates with its anatomical position within this structure [20]. As the polarization angle of skylight directly relates to the sun’s azimuth, this arrangement is essentially equivalent to an array of head-direction cells tethered to a sky-based reference frame (Figure 3b).

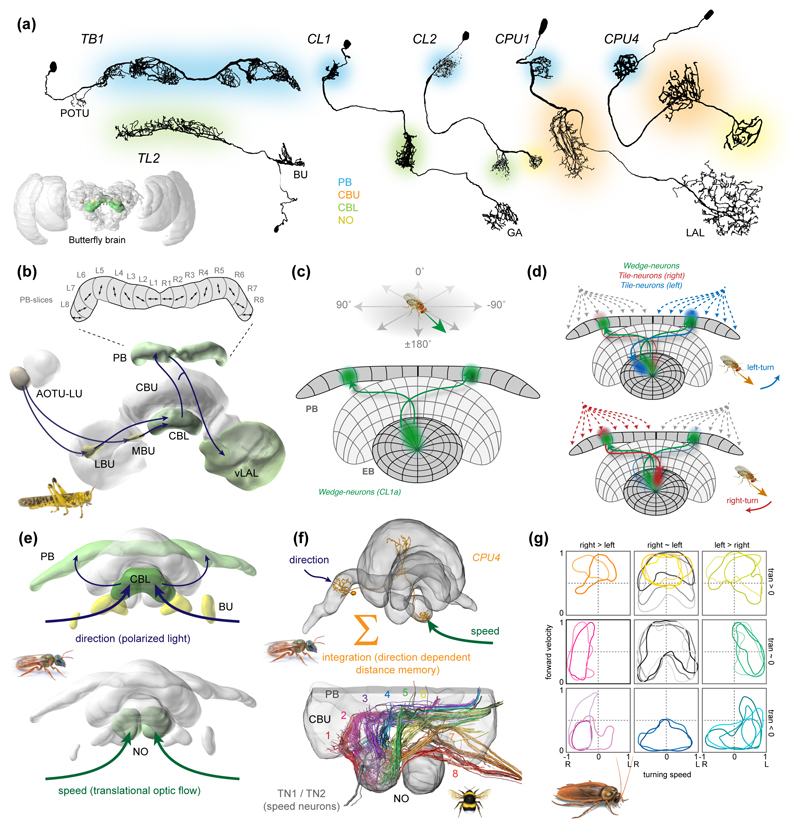

Figure 3. The role of the central complex in navigation.

(a) Conserved cellular components of the central-complex compass circuit. Color of arborizations illustrates innervated central-complex compartment. Neurons are examples from the Monarch butterfly (TB1, TL2, CL1, CPU1; [24]), the desert locust (CL2; [22]), and from the bee Megalopta genalis (CPU4; [18]). Inset: brain of the Monarch butterfly with navigation relevant regions highlighted. (b) Sky-compass pathway downstream of the anterior optic tubercle (AOTU) in the desert locust. Arrows indicate main involved cell types and proposed direction of information flow. Enlargement of protocerebral bridge (PB) shows mapping of polarization tunings (double arrows indicate preferred angle of polarization; [20]. (c) Head-direction cells in Drosophila, as shown by [21]. Image modified after [25]. (d) Angular integration in Drosophila. Rotational velocities of the fly are encoded in tile-neurons and a recurrent feedback loop between wedge- and tile-neurons combined with a one-column offset in anatomical projections causes the wedge neuron bump to update its position in the ellipsoid body due to a tile-neuron activity bias during rotational movements. The wedge-neuron bump moves towards blue during left turns and towards red during right turns (modified after [30]; data from [28,29]). (e) Converging speed and compass information in the bee central complex (Megalopta genalis) [18]. (f) Proposed neural substrate for the home-vector during path integration in bees. Top: CPU4-neurons are suited to integrate speed signal from noduli (NO) with compass signal from PB. Bottom: Each slice of the central complex contains ca. 18 CPU4-neurons, a sufficient number to serve as substrate for an activity based working memory of distances travelled in each compass direction. Data based on block-face electron-microscopy in bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) [18]. (g) Map of future movements in cockroaches. Each plot represents neurons of one functional group, predicting specific combinations of rotational and translational movements (modified from [59]).

Recently, this proposed function of PB-neurons has been directly confirmed in Drosophila [21]. Here, functional imaging was carried out in a set of columnar neurons termed ‘wedge-neurons’ (CL1a-neurons in other insects [17,22–24]; also called E-PG-neurons in flies). These cells transfer information from single slices of the ellipsoid body (lower division of the central body (CBL) in other insects) to single slices of the PB. When the activity of the entire population of these cells was monitored while the fly was walking on an air-suspended ball inside a virtual reality arena, a single bump of activity was revealed within this neuron population, in line with predictions from POL-neurons (Figure 3c). When the fly turned right, the bump moved towards the left, and vice versa. Across the entire population, 360° of the fly’s horizon were represented [21]. This means that the lateral position of the activity bump in the CX predicts the angular orientation of the fly, comprising an internal compass [25]. Importantly, this head-direction signal did not depend on specific visual signals presented in the arena, but was also present in complete darkness [21]. The cells thus integrate self-generated proprioceptive cues with external visual cues into a coherent heading signal. The correlation between the anatomical position of the neural signal and the body-orientation with respect to external cues was largely fixed within single experiments, but was random when compared across individual flies. Thus the phase of the head direction code appears to be reset in each new environment, highly reminiscent of head-direction cells in vertebrates [26], but unlike the POL-neuron based direction map found in migratory locusts, which is consistent across individuals [20]. A second difference between the locust POL-neuron map and the Drosophila head-direction map is that POL-neurons only cover 180° of the horizon in each hemisphere, while the Drosophila cells map 360°. It should be noted that the cell-types in which the POL-mapping was revealed (TB1, CPU1) are likely postsynaptic to the wedge-neuron counterparts (CL1a) [12,19,20]. In fact, CL1a-cells are the only set of columnar cells in locusts, in which a correlation between anatomical position and POL-tuning was not found [22]. Resolving these inter-species disparities will likely illuminate fundamentally conserved principles of how the CX-circuitry computes the head direction signal.

Recent work, again in Drosophila, has brought progress in this respect. Functional imaging in wedge-neurons in combination with another set of CX-columnar cells, the “tile-neurons” (CL2 in other insects [23,24,27]; also P-EN neurons in flies) has established a ring-attractor network as the basis for the head-direction signal [28,29]. Tile-neurons also encode head-direction but their activity is either enhanced or decreased in amplitude depending on the direction of the fly’s angular movements [28–30]. Due to a one-slice offset in the recursive, excitatory connections between both cell-types, an unbalance in the tile-neurons’ activity generated by angular movements shifts the wedge-neuron activity towards a new position in the attractor network, in line with the turning-direction of the fly (Figure 3d). This circuit thus provides a mechanism of how rotational movements are continuously translated into an updated head-direction signal. Additionally to this local excitatory connection between tile- and wedge-neurons the ring-attractor network also requires global inhibition [31]. Several models of the CX, both in Drosophila [28,29,32] and in bees [18], have suggested intrinsic cells of the PB (TB1-cells in insects other than flies) as likely source of this inhibition.

The outlined circuit appears to be tightly conserved. Work in the cockroach CX has uncovered highly similar head-direction cells, albeit without revealing their anatomical identity [26,33]. In dung-beetles [17], monarch butterflies [16] and bees [18], visual compass information is not only transmitted to the CX by neurons homologous to those in flies (ring-neurons) and locusts (TL-neurons), but all other components of the compass network are present as well. This suggests that the delineated head-direction circuit is the basis for encoding body orientation across insects.

Neural correlates of an insect’s desired heading

How is information about body orientation used to guide the next steering decision? To compensate mismatches between desired and current heading, the desired heading also has to be represented in the CX. Little is known how this is achieved neurally. Additionally, goals differ between navigational strategies (Figure 1), strategies continuously compete with each other [34] and switch depending on motivational state [35], making clear predictions about an insect’s momentary navigational goal challenging. Nevertheless, in some behaviors, goal directions are clearly defined.

When insects that use path integration return to their nest after an exploratory foraging trip their goal is the nest, encoded by the home-vector, i.e. an integrated memory of all directional changes and distances covered during the outbound trip. In bees, distances are measured by integrating an optic-flow based speed signal over time [36,37], while sky compass cues serve as directional information [38]. Recent work in the sweat bee Megalopta genalis showed that neurons selectively activated by translational optic flow target the CX-noduli [18]. The bee CX thus receives both speed and compass information (Figure 3e). A set of columnar neurons innervating the noduli and the PB (CPU4-neurons [22–24]; postsynaptic to the speed neurons [18]) have been proposed to integrate both cues and are theoretically suited to generate a distributed memory of the home-vector across the columns of the CX (Figure 3f). In each column, these neurons could accumulate neural activity proportionally to flight speed whenever the bee faces into a specific compass direction [18]. This directionally gated distance-memory would yield a population-coded activity bump that directly represents the bee’s navigational goal. When this hypothetical circuit was implemented as a biologically constrained computational model it indeed yielded a home vector representation in the modeled CPU4-population that could be used to steer the bee back home [18], similar to purely theoretical models [39,40].

Walking insects, such as ants, use a step-counter instead of optic flow to measure distances [41]. Whether neurons homologous to the bee’s speed neurons are activated by these inputs remains to be shown. If this is the case, a common mechanism for integrating speed and direction in path integrating insects seems likely and the activity of CPU4-neurons might generally represent the goal direction during this behavior (Figure 4d).

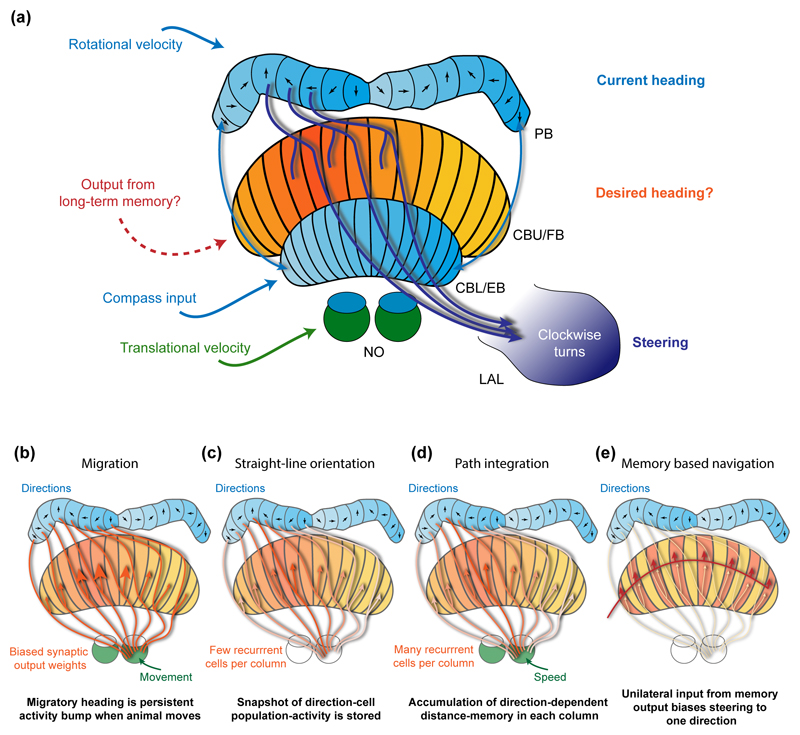

Figure 4. A proposed framework for navigational control.

(a) The central complex can be divided into several functional regions: First, the lower division of central body (CBL) (ellipsoid body (EB) in flies), the protocerebral bridge (PB) and the small subunit of the noduli (NO)) are involved in direction encoding and integrate compass input to the CBL [11,12,16–18,77] with rotational velocity input to the PB [28,29]. Second, the large subunit of the noduli receives translational velocity input (shown in bees [18]). Third, the upper division of the central body (CBU; fanshaped body in flies (FB)) has been proposed to house neurons encoding the desired heading of the animal [18] and receives input from many brain areas, including potential readout from long-term memory. Finally, neurons receiving input in both the PB and the CBU, and project to the lateral accessory lobes (LAL; involved in motor control [64]), are suited to compare current with desired heading and initiate steering [18]. For clarity, inputs are shown on the left side and outputs on the right side only. (b-e) Hypothetical ways by which the desired heading could be computed using a set of columnar cells (CPU4) that receive input in the NO and the PB, while projecting to the CBU. These cells, in principle, could integrate translational velocity with compass information and provide information to the steering cells in the CBU. (b) During long-range migration, synaptic weights of CPU4 output could be genetically fixed to generate a persistent bump of activity in the CBU that drives steering cell activity towards the migratory target direction. The input from the NO ensures that steering towards the migratory heading only occurs when the animal moves fast enough. (c) During straight-line orientation in ball-rolling dung beetles [45], a snapshot of the direction cell activity could be transferred to the CPU4 population when selecting a rolling direction. This stored direction could be maintained via recurrent connections within CX-columns (more than one CPU4 cell per column synapsing onto one another) and drive steering until the snapshot memory decays. (d) Similarly during path integration (but requiring more recurrent connections for increased memory stability), direction and speed information could be integrated during a foraging trip to encode the home-vector, which can be used for steering back to the nest [18]. (e) Finally, output from long-term memory (e.g. panoramic reference images stored in the mushroom bodies) could activate the same steering cells and bias steering towards the direction of the better memory match. As these cells would target the same steering cells as used during path integration, both strategies would be automatically combined (as in [34]).

The memory proposed for encoding the home-vector is based on ongoing activity. Indeed, indications that short-term working-memory is required to recall a navigational goal has also been found in Drosophila in different behavioral paradigms [42,43], most recently also including path integration [44]. Similarly, dung beetles maintain a steady heading when rolling a dung-ball (Figure 2a) and return to their initially chosen direction after disturbance, thus also requiring short-term memory [45]. Generally, activity based short-term memory of navigation directions could be used to compensate for course deviations during any directed movement. Evidence for recovery of directional information after presenting distracting sensory input has been found in CX-neurons of locusts [46]. While the substrate of this memory is not known in any of these examples, CPU4-neurons are potential candidate cells in all cases (Figure 4c,d).

Migratory insects have to maintain a steady heading as well, albeit not for seconds or minutes, but for weeks or months [47,48]. While there is no data revealing the neural substrate of migratory headings in any insect, authors of [18] have speculated that the mechanism suited to encode the home-vector during path integration might also represent migratory heading. By genetically fixing synaptic weights, the output of CPU4-neurons could be biased in a way that generates a hard-wired activity bump across these cells that encodes a stable goal direction (Figure 4b). If relying on a sun compass, this goal direction would have to be shifted by output from the circadian clock in order to compensate the daily movements of the sun across the sky. A model explaining time-compensated migratory headings in Monarch butterflies has been proposed recently [49], although concrete neural substrates remain unresolved. Both models combined provide a framework based on which the neural implementation of migratory headings can be unraveled in the years to come.

Not only acute sensory information drives behavior, but memorized features of the environment are key to many navigation decisions as well, e.g. for image-matching strategies in ants when navigating along fixed foraging routes or during landmark based navigation [50,51]. Such memories are more stable than home-vectors [52] and require synaptic remodeling [53,54]. The major site for such long-term information storage in the insect brain is the mushroom body [55,56]. However, as no prominent connection between the mushroom body and the CX has been found in any insect to date, it remains an open question how mushroom body output could be integrated with representations of current and intended headings in the CX (Figure 4e).

How the brain guides movement

After comparing current and intended headings, the insect brain has to initiate steering movements to compensate mismatches between the two directions. Besides its function in sensory coding, the CX has long been established as a center for locomotion (reviewed in [57]). Recently, work in cockroaches has revealed that neuronal activity in the CX predicts the animal’s imminent movements [58–60]. To achieve this, cockroach CX-neurons were recorded with extracellular electrodes during tethered walking on an air-suspended ball or while freely exploring an experimental arena. This allowed correlating neural activity to ongoing and future locomotor behavior and revealed that many cells are active just before movements are initiated. These neurons could be grouped into functional classes, each of which predicted a specific combination of forward speed and angular velocity, i.e. they essentially generate a map of future positions of the animal [59] (Figure 3g). That this neural activity indeed causes the observed movements was directly demonstrated by observing the animal’s movements while injecting a current via the recording electrodes [59]. Finally, effects on the leg coordination reflexes during those current injections into the CX that would lead to turning of the animal closely resemble the modulation of the same reflexes during natural turning [59]. Neural activity of the CX thus directly modulates thoracic reflexes that underlie turning movements.

Whereas the anatomical identity of these cockroach steering-cells is unknown, a model of the bee’s CX suggests concrete neurons for this function [18]. As mentioned above, during path integration, CPU4-columnar neurons are proposed to serve as memory substrate for the home-vector, while the PB-compass cells likely represent the bee’s current heading. A second type of columnar cell (CPU1) is suited to receive input from both the candidate memory cells and direction cells and are thus ideally suited to compare the bee’s current heading with its goal direction (Figure 4a). Across insects, CPU1-cells converge in the lateral accessory lobes [23,24,61,62], regions known to be involved in motor control (reviewed in [63–65]). Indeed, when tested in simulations this circuit yielded correct steering decision during path integration [18] and thus also outlines how the CX could use its head-direction signal to control steering during navigation behaviors in general.

Highlights.

-

-

Animals compare current and desired headings to initiate steering during navigation.

-

-

The insect central complex (CX) encodes head-direction (current heading).

-

-

A ring-attractor network underlies head-direction signaling.

-

-

The CX compass-circuit is conserved across a wide range of species.

-

-

CX-neurons are also suited to encode desired heading and control steering.

Acknowledgements

The author was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 714599) and by a Junior Project grant from the Swedish Research Council (VR, 621-488 2012- 2213).

References and recommended reading

- 1.Wehner R. Desert ant navigation: how miniature brains solve complex tasks. J Comp Physiol A. 2003;189:579–588. doi: 10.1007/s00359-003-0431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeil J. Visual homing: an insect perspective. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collett M. How desert ants use a visual landmark for guidance along a habitual route. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11638–11643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001401107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labhart T. Polarization-opponent interneurons in the insect visual system. Nature. 1988;331:435–437. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homberg U, Würden S. Movement-sensitive, polarization-sensitive, and light-sensitive neurons of the medulla and accessory medulla of the locust, Schistocerca gregaria. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:329–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.el Jundi B, Pfeiffer K, Homberg U. A distinct layer of the medulla integrates sky compass signals in the brain of an insect. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labhart T, Petzold J, Helbling H. Spatial integration in polarization-sensitive interneurones of crickets: a survey of evidence, mechanisms and benefits. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:2423–2430. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.14.2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homberg U. Evolution of the central complex in the arthropod brain with respect to the visual system. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2008;37:347–362. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfeiffer K, Homberg U. Organization and functional roles of the central complex in the insect brain. Annu Rev Entomol. 2014;59:165–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner-Evans DB, Jayaraman V. The insect central complex. Curr Biol. 2016;26:R453–R457. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinze S. Polarized-light processing in insect brains: Recent insights from the desert locust, the Monarch butterfly, the cricket, and the fruit fly. In: Horváth G, editor. Polarized Light and Polarization Vision in Animal Sciences. Springer; 2014. pp. 61–111. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homberg U, Heinze S, Pfeiffer K, Kinoshita M, el Jundi B. Central neural coding of sky polarization in insects. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2011;366:680–687. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeiffer K, Homberg U. Coding of azimuthal directions via time-compensated combination of celestial compass cues. Curr Biol. 2007;17:960–965. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.el Jundi B, Pfeiffer K, Heinze S, Homberg U. Integration of polarization and chromatic cues in the insect sky compass. J Comp Physiol A. 2014;200:575–589. doi: 10.1007/s00359-014-0890-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinoshita M, Pfeiffer K, Homberg U. Spectral properties of identified polarized-light sensitive interneurons in the brain of the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:1350–1361. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinze S, Reppert SM. Sun compass integration of skylight cues in migratory monarch butterflies. Neuron. 2011;69:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.el Jundi B, Warrant EJ, Byrne MJ, Khaldy L, Baird E, Smolka J, Dacke M. Neural coding underlying the cue preference for celestial orientation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:11395–11400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501272112. [** This work describes the anatomy and physiology of the compass-circuit in the central complex of ball-rolling dung beetles and reveals that sensory stimuli that are used for behavioral responses of the animal are also encoded in the neurons of the central complex. The paper demonstrates a cue hierarchy in the brain that mirrors behavioral relevance.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone T, Webb B, Adden A, Weddig NB, Honkanen A, Templin R, Wcislo W, Scimeca L, Warrant E, Heinze S. An anatomically constrained model for path integration in the bee brain. Curr Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.052. in press. [** With physiology, anatomy, computational modeling and robotics this paper shows that speed (translational optic flow) and compass information (polarized light) converge in the central complex of bees and, together with a set of columnar neurons postsynaptic to the speed-neurons, form the basis of integration speed and direction for path integration. The presented computational model of path integration is fully biologically constrained and tested both in virtual agents and robots.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinze S, Gotthardt S, Homberg U. Transformation of polarized light information in the central complex of the locust. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11783–11793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1870-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinze S, Homberg U. Maplike representation of celestial E-vector orientations in the brain of an insect. Science. 2007;315:995–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1135531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seelig JD, Jayaraman V. Neural dynamics for landmark orientation and angular path integration. Nature. 2015;521:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature14446. [** This seminal paper directly shows that columnar neurons of the central complex (‘wedge’-neurons) encode the body orientation of the fly, both using visual information, but also in complete darkness. This paper established that vertebrate-like head-direction cells indeed also exist in insects and opened the door towards probing the underlying circuitry on a mechanistic level.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinze S, Homberg U. Linking the input to the output: new sets of neurons complement the polarization vision network in the locust central complex. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4911–4921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0332-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinze S, Homberg U. Neuroarchitecture of the central complex of the desert locust: Intrinsic and columnar neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2008;511:454–478. doi: 10.1002/cne.21842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinze S, Florman J, Asokaraj S, el Jundi B, Reppert SM. Anatomical basis of sun compass navigation II: the neuronal composition of the central complex of the monarch butterfly. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:267–298. doi: 10.1002/cne.23214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinze S. Neuroethology: Unweaving the senses of direction. Curr Biol. 2015;25:R1034–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varga AG, Kathman ND, Martin JP, Guo P, Ritzmann RE. Spatial navigation and the central complex: Sensory acquisition, orientation, and motor control. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11:4081. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller M, Homberg U, Kühn A. Neuroarchitecture of the lower division of the central body in the brain of the locust (Schistocerca gregaria) Cell Tissue Res. 1997;288:159–176. doi: 10.1007/s004410050803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green J, Adachi A, Shah KK, Hirokawa JD, Magani PS, Maimon G. A neural circuit architecture for angular integration in Drosophila. Nature. 2017;546:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nature22343. [** Together with [29] this paper reveals that recurrent connections between ‘wedge’ and ‘tile’ neurons of the fly central complex form the basis for integrating rotational movements of the fly into an updated head-direction signal.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner-Evans D, Wegener S, Rouault H, Franconville R, Wolff T, Seelig JD, Druckmann S, Jayaraman V. Angular velocity integration in a fly heading circuit. Elife. 2017;6:e23496. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23496. [** Together with [28] this paper reveals that recurrent connections between ‘wedge’ and ‘tile’ neurons of the fly central complex form the basis for integrating rotational movements of the fly into an updated head-direction signal.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinze S. Neural coding: Bumps on the move. Curr Biol. 2017;27:R409–R412. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SS, Rouault H, Druckmann S, Jayaraman V. Ring attractor dynamics in the Drosophila central brain. Science. 2017;356:849–853. doi: 10.1126/science.aal4835. [* This paper reveals that a ring attractor network that uses local excitation combined with global inhibition underlies the head-direction coding in the Drosophila central complex. Also, it reveals that the head-direction signal is also present during flight (as opposed to earlier walking experiments).] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kakaria KS, de Bivort BL. Ring attractor dynamics emerge from a spiking model of the entire protocerebral bridge. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11:8. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varga AG, Ritzmann RE. Cellular basis of head direction and contextual cues in the insect brain. Curr Biol. 2016;26:1816–1828. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.037. [** This paper demonstrates that head-direction cells also exist in cockroaches. Using extracellular physiology the authors reveal that these neurons share many features with head-direction cells in flies, but also with their mammalian counterparts.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collett M. How navigational guidance systems are combined in a desert ant. Curr Biol. 2012;22:927–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knaden M, Wehner R. Ant navigation: resetting the path integrator. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:26–31. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srinivasan MV. Going with the flow: a brief history of the study of the honeybee's navigational 'odometer'. J Comp Physiol A. 2014;200:563–573. doi: 10.1007/s00359-014-0902-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivasan MV. Where paths meet and cross: navigation by path integration in the desert ant and the honeybee. J Comp Physiol A. 2015;201:533–546. doi: 10.1007/s00359-015-1000-0. [* This review is an excellent summary of our current knowledge of path integration in ants and bees. It illuminates both the sources of directional information as well as distance encoding in these insects, illustrating challenges to be addressed in the future.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evangelista C, Kraft P, Dacke M, Labhart T, Srinivasan MV. Honeybee navigation: critically examining the role of the polarization compass. Philos Trans R Soc Lond, B. 2014;369 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0037. 20130037–20130037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haferlach T, Wessnitzer J, Mangan M, Webb B. Evolving a neural model of insect path integration. Adaptive Behavior. 2007;15:273–287. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldschmidt D, Manoonpong P, Dasgupta S. A Neurocomputational model of goal-directed navigation in insect-inspired artificial agents. Front Neurorobot. 2017;11:e1004683–17. doi: 10.3389/fnbot.2017.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittlinger M, Wehner R, Wolf H. The ant odometer: stepping on stilts and stumps. Science. 2006;312:1965–1967. doi: 10.1126/science.1126912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ofstad TA, Zuker CS, Reiser MB. Visual place learning in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;474:204–207. doi: 10.1038/nature10131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neuser K, Triphan T, Mronz M, Poeck B, Strauss R. Analysis of a spatial orientation memory in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;453:1244–1247. doi: 10.1038/nature07003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim IS, Dickinson MH. Idiothetic Path integration in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.026. [** For the first time, this paper shows that flies are capable of path integration. By detailed analysis of behavioral data, the authors reveal that when returning to a food source, flies track their body movements and, independent of visual cues in the environment, recall the position of the food. Previously, this behavior had been mainly associated with bees and ants. This work therefore elevates the relevance of Drosophila as a model organism for a wider range of insect behaviors.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.el Jundi B, Foster JJ, Khaldy L, Byrne MJ, Dacke M, Baird E. A snapshot-based mechanism for celestial orientation. Curr Biol. 2016;26:1456–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.030. [* This elegant behavioral study demonstrates that ball-rolling dung beetles use the current constellation of celestial cues as reference for choosing a navigation direction. This ‘snapshot’ is taken while the beetles perform a characteristic ‘dance’ on top of the dung ball and does not depend on a naturalistic arrangement of skylight compass cues.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bockhorst T, Homberg U. Interaction of compass sensing and object-motion detection in the locust central complex. J Neurophysiol. 2017;118:496–506. doi: 10.1152/jn.00927.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warrant EJ, Frost B, Green K, Mouritsen H, Dreyer D, Adden A, Brauburger K, Heinze S. The Australian Bogong moth Agrotis infusa: A long-distance nocturnal navigator. Front Behav Neurosci. 2016;10:77. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reppert SM, Guerra PA, Merlin C. Neurobiology of monarch butterfly migration. Annu Rev Entomol. 2016;61:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shlizerman E, Phillips-Portillo J, Forger DB, Reppert SM. Neural integration underlying a time-compensated sun compass in the migratory monarch butterfly. Cell Rep. 2016;15:683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menzel R, de Marco RJ, Greggers U. Spatial memory, navigation and dance behaviour in Apis mellifera. J Comp Physiol A. 2006;192:889–903. doi: 10.1007/s00359-006-0136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collett TS, Collett M. Memory use in insect visual navigation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:542–552. doi: 10.1038/nrn872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ziegler PE, Wehner R. Time-courses of memory decay in vector-based and landmark-based systems of navigation in desert ants, Cataglyphis fortis. J Comp Physiol A. 1997;181:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Groh C, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA, Rössler W. Age-related plasticity in the synaptic ultrastructure of neurons in the mushroom body calyx of the adult honeybee Apis mellifera. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:3509–3527. doi: 10.1002/cne.23102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stieb SM, Muenz TS, Wehner R, Rössler W. Visual experience and age affect synaptic organization in the mushroom bodies of the desert ant Cataglyphis fortis. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:408–423. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Menzel R. The insect mushroom body, an experience-dependent recoding device. J Physiol Paris. 2014;108:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mizunami M, Weibrecht JM, Strausfeld NJ. Mushroom bodies of the cockroach: their participation in place memory. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:520–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strausfeld NJ. A brain region in insects that supervises walking. Progress in Brain Res. 1999;123:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62863-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bender JA, Pollack AJ, Ritzmann RE. Neural activity in the central complex of the insect brain is linked to locomotor changes. Curr Biol. 2010;20:921–926. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martin J, Guo P, Mu L, Harley CM, Ritzmann RE. Central-complex control of movement in the freely walking cockroach. Curr Biol. 2015;25:2795–2803. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.044. [** This paper is a true milestone in central-complex research and demonstrates that neurons in this brain region not only predict concrete movements of the cockroach, but actually cause these movements. Moreover, the authors show that the descending signals by central-complex neurons alter specific thoracic reflexes to enable turning movements.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo P, Ritzmann RE. Neural activity in the central complex of the cockroach brain is linked to turning behaviors. J Exp Biol. 2013;216:992–1002. doi: 10.1242/jeb.080473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wolff T, Iyer NA, Rubin GM. Neuroarchitecture and neuroanatomy of the Drosophila central complex: A GAL4-based dissection of protocerebral bridge neurons and circuits. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:997–1037. doi: 10.1002/cne.23705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lin C-Y, Chuang C-C, Hua T-E, Chen C-C, Dickson BJ, Greenspan RJ, Chiang A-S. A comprehensive wiring diagram of the protocerebral bridge for visual information processing in the Drosophila brain. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1739–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Namiki S, Kanzaki R. Comparative neuroanatomy of the lateral accessory lobe in the insect brain. Front Physiol. 2016;7:244. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Namiki S, Kanzaki R. The neurobiological basis of orientation in insects: insights from the silkmoth mating dance. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2016;15:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Namiki S, Iwabuchi S, Pansopha Kono P, Kanzaki R. Information flow through neural circuits for pheromone orientation. Nat Comm. 2014;5:5919. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dacke M, Baird E, Byrne MJ, Scholtz CH, Warrant EJ. Dung beetles use the Milky Way for orientation. Curr Biol. 2013;23:298–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Foster JJ, el Jundi B, Smolka J, Khaldy L, Nilsson D-E, Byrne MJ, Dacke M. Stellar performance: mechanisms underlying Milky Way orientation in dung beetles. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2017;372 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0079. 20160079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwarz S, Narendra A, Zeil J. The properties of the visual system in the Australian desert ant Melophorus bagoti. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2011;40:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chapman JW, Reynolds DR, Mouritsen H, Hill JK, Riley JR, Sivell D, Smith AD, Woiwod IP. Wind selection and drift compensation optimize migratory pathways in a high-flying moth. Curr Biol. 2008;18:514–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Müller M, Wehner R. Wind and sky as compass cues in desert ant navigation. Naturwissenschaften. 2007;94:589–594. doi: 10.1007/s00114-007-0232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ritzmann RE, Ridgel AL, Pollack AJ. Multi-unit recording of antennal mechano-sensitive units in the central complex of the cockroach, Blaberus discoidalis. J Comp Physiol A. 2008;194:341–360. doi: 10.1007/s00359-007-0310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Knaden M, Graham P. The sensory ecology of ant navigation: From natural environments to neural mechanisms. Annu Rev Entomol. 2016;61:63–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yarger AM, Fox JL. Dipteran halteres: Perspectives on function and integration for a unique sensory organ. Integr Comp Biol. 2016;56:865–876. doi: 10.1093/icb/icw086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Homberg U. Sky compass orientation in desert locusts—Evidence from field and laboratory studies. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:346. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00346. [* This interesting review summarizes, for the first time since the early work in the 1950s, all behavioral evidence for compass orientation in desert locusts, both resulting from field studies as well as from laboratory experiments. The author therefore provides much needed context for the wealth of neurophysiological studies of compass processing in that species.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Collett M, Chittka L, Collett TS. Spatial memory in insect navigation. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Menzel R, Kirbach A, Haass W-D, Fischer B, Fuchs J, Koblofsky M, Lehmann K, Reiter L, Meyer H, Nguyen H, et al. A common frame of reference for learned and communicated vectors in honeybee navigation. Curr Biol. 2011;21:645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sakura M, Lambrinos D, Labhart T. Polarized skylight navigation in insects: model and electrophysiology of e-vector coding by neurons in the central complex. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:667–682. doi: 10.1152/jn.00784.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]