Abstract

Introduction:

The necessity of culturally competent Internet Cancer Support Groups (ICSGs) for ethnic minorities has recently been highlighted in order to increase its attractivity, and usage. The purpose of this study was to determine the preliminary efficacy of a culturally tailored registered nurse (RN) moderated ICSG for Asian American breast cancer survivors (ICSG-AA) in enhancing the women’s breast cancer survivorship experience.

Methods:

The study included two phases: (a) a usability test and an expert review; and (b) a randomized controlled pilot intervention study. The usability test was conducted among five Asian American breast cancer survivors using a 1-month online forum, and the expert review was conducted among five experts using the Cognitive Walkthrough method. The randomized controlled pilot intervention study (a pre-test and post-test design) was conducted among 65 Asian American breast cancer survivors. The data were analyzed using content analysis and descriptive and inferential statistics including the repeated ANOVA.

Results:

All users and experts positively evaluated the program, and provided their suggestions for the display, educational contents, and user-friendly structure. There were significant positive changes in support care needs and physical and psychological symptoms (p < 0.05) of the control group. There were significant negative changes in the uncertainty level of the intervention group (p < 0.10). Controlling for background and disease factors, the intervention group showed significantly greater improvements than the control group in physical and psychological symptoms and quality of life (p < 0.10).

Discussion:

The findings supported the positive effects of ICSGs on support care needs, psychological and physical symptoms, and quality of life.

Keywords: Web-based intervention, online intervention, issues, nursing

Introduction

Despite few studies on Asian American breast cancer survivors, it is well known that these women shoulder unnecessary burden of breast cancer because they rarely complain about symptoms or pain, delay seeking help until symptoms become severe, and rarely ask or get support due to their cultural values and beliefs and language barriers. 1–5 Subsequently, they report a lower quality of life compared to Whites.6–15 The association of poor quality of life with fewer sources of support is also higher for Asian Americans than for Whites.7,12–14,16–18 These demonstrate a definite need for support in this specific population.

As an important source of support, Internet cancer support groups (ICSGs) have been found to provide emotional support, information and interactions with peers and health care professionals for cancer survivors, including those with breast cancer.19–27 Although racial/ethnic minorities were reported to have much greater benefits (compared to Whites) from participating in ICSGs, the use of ICSGs by ethnic minorities including Asian Americans is minimal mainly because most of the ICSGs have been developed for Whites.19,21–24,26–30 Subsequently, the necessity of culturally competent ICSGs for racial/ethnic minorities that could increase the appeal and accessibility of ICSGs (and therefore their use and subsequent support) has been highlighted.29–33 Here, cultural competence refers to the acknowledgment and affirmation of cultural sensitivity imbedded in cultural knowledge.34

Based on previous studies on Asian cancer patients’ attitudes toward ICSGs,35,36 the research team has developed a theory-driven culturally tailored ICSG for Asian American breast cancer survivors (ICSG-AA) that: (a) incorporates racial/ethnic-specific contextual factors, (b) is assisted and monitored by culturally matched health care providers, and (c) integrates existing evidence-based educational modules/materials from scientific/health authorities that have been validated and tested in previous research.

The purposes of this study were to pilot-test the culturally tailored ICSG-AA for breast cancer survivors and determine the preliminary efficacy of the ICSG-AA in enhancing the women’s breast cancer survivorship experience. Among over 71 sub-ethnic groups of Asian Americans 40, only three sub-ethnic groups (Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese) were selected for this study for the convenience of the approach (e.g., language). Chinese are the largest sub-ethnic group within Asian Americans,37,38 Koreans are the fastest growing sub-ethnic group within Asian Americans,37,38 and Japanese are the sub-ethnic group at the highest risk of breast cancer within Asian Americans.6,7,10,39 The specific aims and hypotheses of this study were to:

Aim #1. Qualitatively evaluate the ICSG-AA through a usability test and an expert review.

Aim #2. Determine the preliminary efficacy of the ICSG-AA in enhancing survivorship outcomes (perceived social support, perceived interactions, support care needs, uncertainty, perceived self-efficacy, physical and psychological symptoms, pain, and quality of life) among Asian American breast cancer survivors.

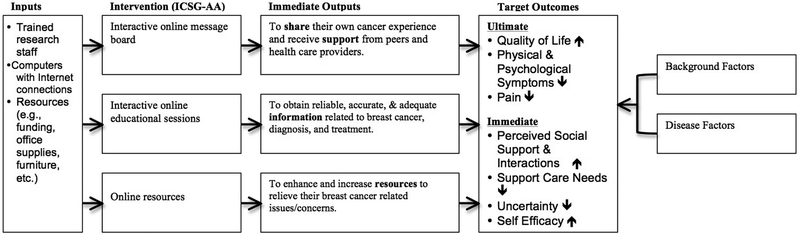

The proposed study was theoretically guided by a comprehensive program theory (see Figure 1) that specifically explained the relationships between the use of ICSGs and its targeted outcomes. The program theory was developed based on the Use of Internet Cancer Support Groups model (UICSG model).40 As illustrated in Figure 1, the ICSG-AA included three components: (a) online message boards; (b) online educational sessions; and (c) online resources. Based on the literature on ICSGs,19–27 the three components were expected to result in changes in the women’s survivorship outcomes. In this study, after the ICSG-AA was preliminarily evaluated through a usability test and an expert review (Aim #1) and further refined based on the preliminary evaluation, the preliminary efficacy of the ICSG-AA was determined in improving the women’s survivorship outcomes while controlling background factors and disease factors (Aim #2).

Figure 1.

The Programss Theory for the ICSG-AA.

The ICSG for Asian American Breast Cancer Survivors (ICSG-AA)

The ICSG-AA targeted three factors (language, sub-ethnicity, and country of birth) that influenced the use of ICSGs by Asian American breast cancer survivors and aimed to provide support in three aspects (emotional support, information, and interactions). The educational sessions were chosen while considering the women’s cultural attitudes found in former studies of the research team.2,35,36 The content was differently constructed by sub-ethnic group based on the cultural findings from previous studies. For example, because Chinese American women tended to use Chinese herbal medicine for their symptom management in previous studies, we have added an education module on Chinese herbal medicine for Chinese participants. These sessions will provide correct and updated information on breast cancer and treatment/ management strategies so that stigmatization could be reduced by correcting misinformation. Culturally sensitive and relevant contents (e.g., Red Ginseng, herbal medicine, Acupuncture, etc.) were incorporated into the ICSG-AA. Four languages were used in ICSG-AA: English, Mandarin Chinese, Korean, and Japanese. Mandarin Chinese is a primary language in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong; Korean is the primary language in South Korea; and Japanese is the primary language in Japan. The messages that were posted on the online forum site were translated using the Google translator first, and the accuracy of the translation was ensured by bilingual researchers with doctoral or master’s degrees in nursing. Presentation styles were tailored to Asian culture based on the feedback of Asian participants from the former studies.36 Also, the moderator used culture-specific examples from the research team’s previous studies to discuss specific issues related to breast cancer survivorship (e.g., Chinese Americans believe that they need to hide their disease because it could affect their children’s future marriage). The ICSG-AA used a free-form matrix information architecture41 and included menus based on the three components: (a) interactive online message board; (b) interactive online educational sessions; and (c) online resources. We used Graphic User Interface controls42 for the input from and/or the output to the participants. All the components of ICSG-AA were built using the Ruby on Rails (ROR)43 framework and the Xen hypervisor. 44 The educational sessions integrated existing evidence-based educational modules/materials from scientific/health authorities (National Cancer Institute, National Library of Medicine, American Cancer Society, etc.) that had already been validated. The educational sessions and links to Internet resources related to breast cancer survivorship were available on the project website, and the participants were allowed to use them at any time and at their convenience. A Registered Nurse (RN) moderated the discussion board to discuss individual educational modules and provided the answers for the questions from the participants with consultation with two medical doctors. The RN also provided individual coaching/support related to survivorship through weekly emails to each participant with consultation with two medical doctors. The online resources included 20 Web links in English and 15 Web links in languages other than English to the resources related to breast cancer survivorship (especially for Asian Americans).

Methods

The study included two phases: (a) a usability test and an expert review (Phase 1); and (b) a randomized controlled intervention study (Phase 2). The study was conducted from January 2014 to November 2015. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the institute where the researchers were affiliated.

Phase 1: The Usability Test & Expert Review

For a usability test, the first five Asian American breast cancer survivors who participated in previous studies of the research team and who agreed to evaluate an early version of the ICSG-AA, were involved in a one-month-long online forum. These participants did not know each other; the previous studies were descriptive studies that involved only one time survey. At the beginning of the online forum, participants were asked to visit the forum site, use the Web-based program, and post messages with their evaluation of the program within a month. On the forum site, a total of 7 topics related to specific areas for which the users’ evaluation was needed were posted: (a) the overall structure of the ICSG-AA, (b) preferences for color, designs, and menus, (c) preferences for contents, (d) technical support and difficulties, (e) areas for additional content, (f) preferences for links to Internet resources, and (g) other issues that should be considered. The messages were analyzed using content analysis.45 This type of early evaluation of a program requires 5 to 10 participants from among the target users.46 Studies have indicated that 80–90% of usability problems can be identified by about 5–10 participants.46

For the expert evaluation, the Cognitive Walkthrough method,47 was used, which concentrated on the difficulties which users might experience in learning to operate the program. First, a total of five experts in breast cancer survivorship (oncologists) were recruited from the faculty of the institute where the researchers were affiliated. Then, they were sent the Web address of the program and asked to provide their evaluation on the program. All the experts were asked to provide their written feedback by email. Their evaluation was sought on: (a) components, (b) presentation style, (c) contents, and (d) any other concerns/issues. The emails were printed out as transcripts, and analyzed using the content analysis.45 Five experts are an adequate number for this type of expert evaluations.48 Then, based on the findings from Phase 1, the research team made decisions on the refinement of specific areas, which were incorporated into further development of the program.

Phase 2: The Randomized Controlled Trial

Study design.

Phase 2 adopted a randomized repeated measures pretest/posttest control group design. This study consisted of two groups of research participants: (a) 30 Asian American breast cancer survivors who did not use the ICSG-AA, but used Internet resources related to Asian Americans’ daily life (a control group); (b) 35 Asian American breast cancer survivors who used the ICSG-AA and Internet resources related to Asian Americans’ daily life (an intervention group). The Internet resources were those related to daily life concerns/issues of Asian Americans (e.g., news in Asian countries, Asian businesses in the U.S.) in specific residence areas (e.g., New York Asian American portal, Koreanportal.com, Asian American LA portal, etc.). The links were provided through the project website, and the participants (both the control and intervention group) were asked to visit and use the links.

Samples and settings.

A total of 65 Asian American breast cancer survivors were recruited and randomized to the intervention or control groups. The participants were recruited through the Internet and physical settings where Asian American breast cancer survivors gathered (e.g., Internet communities for Asian American breast cancer survivors, Facebook sites, local clinics, American Cancer Society local chapters, etc.). To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, with 80% power, and a type I error rate equal to 0.00625 to account for 9 outcome measures modeled within two hypotheses, group sample sizes of 105 each would have enough power to detect a difference of 0.5 between group means overall in the follow-up period. However, considering the study period and the inherent explorative nature of the study, we included only 65 women (50 would be adequate for a pilot intervention study49). The participants were self-reported women aged 21 years and older who had a breast cancer diagnosis in the past 5 years; could read and write English, Mandarin Chinese, Korean or Japanese; had access to the Internet; and identified their sub-ethnicity as Chinese, Korean, or Japanese. Eligible participants were included regardless of their current treatment status because the ICSG-AA could be used by those in all stages of treatment. The participants were limited to those who have survived less than 5 years because those who have survived more than 5 years have different needs from those who have survived less than 5 years.

Instruments.

Other covariates that were considered in determining the effect of the ICSG-AA on dependent variables included background factors (BF) and disease factors (DF). The BF were measured using 14 questions (e.g., age, gender, education, religion, family income, etc.), and the DF were measured using 8 questions (e.g., general health, diagnosis of breast cancer, length of time since diagnosis, stage of cancer, etc.).

The outcome variables included perceived social support, perceived interactions, support care needs, uncertainty, perceived self-efficacy, physical and psychological symptoms, pain, and quality of life. Multiple instruments were used: the Personal Resource Questionnaire (to measure Perceived social support),50 the Perceived Isolation Scale51 (to measure perceived interactions), the Support Care Needs Survey-34 Short Form124 (to measure support care needs),52 the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale-Community53(to measure uncertainty), the Self-efficacy Items of the Cancer Behavior Inventory54 (to measure perceived self-efficacy), the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Short Form55 (to measure physical and psychological symptoms), the Brief Pain Inventory56 (to measure pain), and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale-Breast Cancer57 (to measure quality of life). The reliability and validity of all the instruments have been established among Asian Americans. Cronbach’s alpha of individual instrument ranged from 0.76 to 0.96 among Asian Americans.

Data collection procedures.

When potential participants visited the Web site, they were asked to review the “informed consent” and click the “I agree to participate” button if they agreed. Then, after checking them against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, only those who met the criteria were automatically randomized into two groups using a computerized random table loaded on the server. The women were asked to fill out the questionnaire. Then, they were provided with IDs and passwords. Both groups were provided with an electronic instruction sheet on when they would need to come back and fill out the questionnaires and/or use the program. Also, both groups were provided with and asked to use the selected Internet resources related to Asian Americans’ daily life. The intervention group used the program for 1 month. Two weeks before the end of the first month, both groups were contacted and asked to fill out the next set of the instruments by the end of the first month. The mean time for completing the survey each time was about 30 minutes, but the participants were allowed to stop the survey at any time, and come back to complete the surveys at their convenience.

Data analysis.

The two datasets collected from each participant were labeled “Pre” and “Post.” The survey questionnaires were coded automatically through the REDCap system. The study data were analyzed using the SPSS 22.0 statistical software. The descriptive analyses were conducted to examine the frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations of major variables. The repeated ANOVA was used to examine the efficacy of the ICSG-AA in enhancing survivorship outcomes (perceived social support, perceived interactions, support care needs, uncertainty, perceived self-efficacy, physical and psychological symptoms, pain, and quality of life) of Asian American breast cancer survivors. The repeated-measures ANOVA was used to assess the violence of independence of multiple observations (often seen in longitudinal studies) 65. The preliminary analysis showed no violations of the assumptions on normal distributions and homogeneity of variances.

Results

Phase 1

All users and experts positively evaluated the program, and provided their suggestions for the display, educational contents, and user-friendly structure. All of them were satisfied with the display, structure, and titles used in the program. Yet, the users suggested the inclusion of additional educational modules and Internet resources for Asian American breast cancer survivors (e.g., sleep problems, more information on cancer in general, changing lifestyle after cancer treatment, coping with loved ones, how to strengthen mental state, and exercises to recover). Experts also suggested the inclusion of additional Internet resources for Asian American breast cancer survivors (e.g., Asian communities’ religious/spiritual groups, mental health links, loss and grief networks/supports, and the OncoLink). They suggested additional educational modules on insomnia, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), family perspectives, mental health information, loss and grief preparation, fear about death, cultural/religious/spiritual perspectives, genetic testing, psychosocial topics, and after treatment topics. Based on the findings from Phase 1, the ICSG-AA was further refined to include additional educational modules and links related to Chinese herbal medicine, genetic testing, grief and mourning, insomnia, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Phase 2

The participants’ baseline information is summarized in Table 1. There were significant positive changes in support care needs (F = 22676.20, p < 0.01) as well as physical and psychological symptoms (F = 309.11, p < 0.05) of the control group from the pre-test to the post-test (see Table 2). There were significant negative changes in the uncertainty level of the intervention group (F = 127.30, p < 0.10) from the pre-test to the post-test (see Table 2). Controlling for background and disease factors, the intervention group showed significantly greater improvements than the control group in physical and psychological symptoms (F = 3.16, p < 0.10) and quality of life (F = 3.31, p < 0.10) from the pre-test to the post-test (Table 3). There were no significant associations between the total number of visits or the total amount of time spent for the intervention and the study’s outcome variables. However, there were significant associations between the total amount of time spent on the intervention and family income (r = 0.56, p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and baseline information of participants

| Characteristics | Control (N = 30) |

Intervention (N = 35) |

Total (N = 65) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or N (%) | |||

| Age (years) | 48.0 ± 11.1 | 46.1 ± 10.6 | 47.0 ± 10.8 |

| Born in U.S. (Yes)* | 5 (8.5) | 14 (23.7) | 19 (32.2) |

| Sub-ethnicity | |||

| Chinese | 13 (21.0) | 15 (24.2) | 28 (45.2) |

| Korean | 6 (9.7) | 6 (9.7) | 12 (19.4) |

| Japanese | 3 (4.8) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (8.1) |

| Other | 5 (8.1) | 11 (17.7) | 16 (25.8) |

| Educational status | |||

| Below high school | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) |

| High school graduated | 8 (12.5) | 7 (11.0) | 15 (23.4) |

| College graduated | 10 (15.6) | 13 (20.3) | 23 (35.9) |

| Graduate degree | 10 (15.6) | 15 (23.4) | 25 (39.1) |

| Marital status** | |||

| Single | 2 (3.2) | 3 (4.8) | 5 (7.9) |

| Married | 22 (34.9) | 24 (38.1) | 46 (73.0) |

| Divorced/separated/no longer partnered | 4 (6.3) | 8 (12.7) | 12 (19.0) |

| Marital months (months) | 175.1 ± 167.3 | 226.5 ± 155.7 | 204.0 ± 160.3 |

| Employment status (Yes) | 12 (19.4) | 22 (35.5) | 34 (54.8) |

| Religion (Yes) | 14 (22,2) | 13 (20.3) | 27 (42.2) |

| Amount of family income (dollars) | 77140.6 ± 57455.0 | 85115.4 ± 62454.0 | 81853.0 ± 59904.4 |

| Degree of income sufficiency (Sufficient) | 20 (33.9) | 23 (35.9) | 43 (72.9) |

| Asian in the community (Yes) | 17 (28.8) | 19 (32.2) | 36 (61.0) |

| Residential type | |||

| Urban | 18 (29.5) | 24 (39.3) | 42 (68.9) |

| Rural | 8 (13.1) | 7 (11.5) | 15 (24.6) |

| Other | 1 (1.6) | 3 (4.9) | 4 (6.6) |

| Use of facility (Yes) | 24 (39.3) | 32 (52.5) | 56 (91.8) |

| Degree of perceived health (Healthy) | 15 (24.6) | 21 (34.4) | 36 (59.0) |

| Invasive breast cancer (Yes) | 18 (31.0) | 25 (43.1) | 43 (74.1) |

| Receiving cancer treatment (Yes) | 29 (44.6) | 30 (46.2) | 59 (90.8) |

| Taking Medicine (Yes) | 18 (31.6) | 24 (42.1) | 42 (73.7) |

| Having cancer pain (Yes) | 11 (18.3) | 16 (26.7) | 27 (45.0) |

Note. SD = standard deviation

p < 0.05,

p < 0.10 indicate the significant differences between groups

Table 2.

Difference in levels of ultimate outcomes and immediate outcomes by assessment points

| Group | Variable | Assessment point | Mean (SE) | 95% Confidence Interval | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Control group | Support care needs | Pre | 116.53 | 10.46 | −16.37 | 249.53 | 22676.2*** | 0.004 |

| Post | 104.00 | 10.62 | −30.97 | 238.97 | ||||

| Physical and psychological symptoms | Pre | 4.83 | 1.73 | −17.19 | 26.85 | 309.11** | 0.036 | |

| Post | 8.08 | 1.68 | −13.24 | 29.41 | ||||

| Quality of life | Pre | 71.17 | 1.21 | 55.79 | 86.54 | 0.010 | 0.937 | |

| Post | 75.50 | 3.09 | 36.52 | 114.48 | ||||

| Pain | Pre | 54.33 | 14.26 | −126.90 | 235.56 | 0.007 | 0.945 | |

| Post | 64.00 | 0.24 | 60.96 | 67.04 | ||||

| Perceived social support | Pre | 86.25 | 1.00 | 73.53 | 98.97 | 0.241 | 0.710 | |

| Post | 84.58 | 1.72 | 62.75 | 106.41 | ||||

| Perceived interactions | Pre | 19.83 | 0.66 | 11.48 | 28.19 | 34.898 | 0.107 | |

| Post | 20.83 | 0.57 | 13.62 | 28.05 | ||||

| Uncertainty | Pre | 72.25 | 0.99 | 59.72 | 84.78 | 0.070 | 0.835 | |

| Post | 73.50 | 2.64 | 39.90 | 107.10 | ||||

| Perceived self efficacy | Pre | 92.33 | 4.86 | 30.64 | 154.03 | 0.428 | 0.631 | |

| Post | 94.17 | 3.68 | 47.48 | 140.87 | ||||

| Intervention group | Support care needs | Pre | 108.57 | 4.13 | 56.10 | 161.04 | 0.040 | 0.874 |

| Post | 103.14 | 4.88 | 41.10 | 165.19 | ||||

| Physical and psychological symptoms | Pre | 4.25 | 0.28 | 0.74 | 7.76 | 0.071 | 0.834 | |

| Post | 4.50 | 0.91 | −7.03 | 16.03 | ||||

| Quality of life | Pre | 70.86 | 1.27 | 54.73 | 86.99 | 9.143 | 0.203 | |

| Post | 66.32 | 0.42 | 61.01 | 71.63 | ||||

| Pain | Pre | 59.71 | 3.33 | 17.35 | 102.08 | 16.568 | 0.153 | |

| Post | 58.00 | 2.30 | 28.82 | 87.18 | ||||

| Perceived social support | Pre | 83.07 | 2.03 | 57.34 | 108.81 | 0.076 | 0.829 | |

| Post | 82.21 | 4.28 | 27.86 | 136.57 | ||||

| Perceived interactions | Pre | 19.64 | 0.21 | 16.97 | 22.31 | 4.376 | .284 | |

| Post | 19.86 | 0.43 | 14.46 | 25.26 | ||||

| Uncertainty | Pre | 37.36 | 1.06 | 53.84 | 80.87 | 127.304* | 0.056 | |

| Post | 66.36 | 0.96 | 54.15 | 78.57 | ||||

| Perceived self efficacy | Pre | 106.00 | 2.41 | 75.43 | 136.57 | 0.829 | 0.530 | |

| Post | 108.79 | 0.76 | 99.15 | 118.42 | ||||

Note. SE = Standard error; Pre = baseline; Post = timepoint 1

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10 indicate the significant differences by assessment points

Table 3.

Differences in outcome variables between assessment points (Post-Pre) by groups

| Variable | Group | Mean (SE) | 95% Confidence Interval |

F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

||||||

| Support care needs | Control | 15.708 | 7.175 | 0.207 | 31.209 | 1.601 | 0.228 |

| Intervention | 4.089 | 4.214 | −5.015 | 13.194 | |||

| Physical and psychological symptoms | Control | −3.202 | 1.289 | −5.986 | −0.417 | 3.158* | 0.099 |

| Intervention | −0.271 | 0.757 | −1.906 | 1.365 | |||

| Quality of life | Control | −8.687 | 6.477 | −22.680 | 5.305 | 3.314* | 0.092 |

| Intervention | 6.402 | 3.804 | −1.816 | 14.620 | |||

| Pain | Control | −5.531 | 5.581 | −17.588 | 6.526 | 0.587 | 0.457 |

| Intervention | −0.058 | 3.278 | −7.140 | 7.023 | |||

| Perceived social support | Control | −0.927 | 2.501 | −6.331 | 4.476 | 0.819 | 0.382 |

| Intervention | 1.969 | 1.469 | −1.205 | 5.143 | |||

| Perceived interactions | Control | −0.891 | .755 | −2.522 | 0.740 | 0.426 | 0.526 |

| Intervention | −0.261 | .443 | −1.219 | 0.697 | |||

| Uncertainty | Control | −0.326 | 2.340 | −5.381 | 4.729 | 0.096 | 0.761 |

| Intervention | 0.604 | 1.374 | −2.365 | 3.573 | |||

| Perceived self efficacy | Control | −1.979 | 9.182 | −21.814 | 17.857 | 0.004 | 0.950 |

| Intervention | −2.723 | 5.393 | −14.374 | 8.927 | |||

Note. SE = Standard error; Pre = baseline; Post = timepoint 1

p < .10 indicate the significant differences by groups

Discussion

The finding that all the users and experts positively evaluated the ICSG-AA agrees with the literature supporting the efficacy of ICSGs.28,32,58 Also, this finding agrees with the studies that reported health care providers’ and users’ high acceptance of Web-based applications including decision support systems.59–61

Despite reported positive findings on ICSGs, the literature has been inconsistent on the effectiveness of ICSGs on patients’ survivorship outcomes. Some found no significant improvement in patients’ outcomes (e.g., coping to cancer, perceived health, quality of life, psychological health, etc.).62,63 Others reported the effectiveness of ICSGs in enhancing survivorship outcomes such as self-reported symptoms, self-esteem, self-efficacy, functional status, and quality of life and in decreasing the needs for information and communication, uncertainty, and social isolation.24,28,64 The findings of this study are consistent with the direction of the later studies that reported positive effects of ICSGs on survivorship outcomes of patients.24,28,64 Those who used ICSGs showed significant improvements than the control group in survivorship outcomes (physical and psychological symptoms and quality of life), when background and disease factors were controlled.

Based on the literature, it was originally expected that the intervention group would show negative changes in support care needs and physical and psychological symptoms while the control group would show no change.24,28,64 However, in this study, the intervention group did not demonstrate a significant change in their support care needs while the control group showed significant increases in support care needs and physical and psychological symptoms. In other words, without the ICSG-AA, Asian American breast cancer survivors’ support care needs and physical and psychological symptoms would have increased over time. Furthermore, the findings reported that the ICSG-AA significantly reduced the uncertainty level of the intervention group. The findings support the necessity of a culturally tailored ICSG for Asian American breast cancer survivors to reduce their support care needs, physical and psychological symptoms, and uncertainty, subsequently enhancing their quality of life.

This study has several limitations. First of all, the sample size tends to be small because of its inherent nature as a pilot study. Second, patient outcomes were assessed by self-reports. Finally, the study is limited in generalizability because the study participation required the ability to use computers or smart phones. This may have led to a bias towards more favorable outcomes of the intervention group compared to general populations. Thus, through future studies, the ICSG-AA needs to be further developed with more refined cultural tailoring, and its efficacy needs to be tested in a larger sample of diverse groups of Asian American breast cancer survivors. Furthermore, its influences on patient outcomes need to be further assessed using objective measurement methods rather than the self-reports that were used in this study.

Conclusion

This study supported the user acceptance and satisfaction with the ICSG-AA and the preliminary efficacy of the ICSG-AA in enhancing Asian American breast cancer survivors’ survivorship experience. Based on the findings, we suggest that health care providers consider using ICSGs in enhancing the survivorship experience of breast cancer survivors in racial/ethnic minority populations including Asian Americans. As this study reported, ICSGs could be acceptable by racial/ethnic minority populations, and could be effective in enhancing their survivorship experience. The inconsistent findings on the effectiveness of ICSGs on survivorship outcomes in the literature might come from lack of cultural tailoring in existing studies. In this sense, health care providers need to culturally tailor ICSGs for future use in racial/ethnic minorities.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Population Science Pilot Project Award, the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA016520) and the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania. The Chinese translation process involved in the study was also funded by the Chang Gung Medical Research Foundation (BMRPA50 & ZZRPF3C0011). We greatly appreciate all the efforts made by our research assistants including Ms. Xiaopeng Ji, Dr. Jingwen Zhang, Ms. Sangmi Kim, and Ms. Mihea Park.

Footnotes

The authors have no disclosures to make.

Reference

- 1.Matsuno RK, Costantino JP, Ziegler RG, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in Asian and Pacific Islander American women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103(12):951–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Im E-O, Lee EO, Park YS. Korean women’s breast cancer experience. West J Nurs Res 2002;24(7):751–765; discussion 766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang BL, & Zhan L Chinese In: Caring for Women Cross-Culturally. FA Davis Company, 2003, p.92–107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagawa-Singer M, Wellisch DK, Durvasula R. Impact of breast cancer on Asian American and Anglo American women. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1997;21(4):449–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashing-Giwa KT, Kagawa-Singer M, Padilla GV, et al. The impact of cervical cancer and dysplasia: a qualitative, multiethnic study. Psychooncology. 2004;13(10):709–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Institute. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. (2012, accessed 31 December 2013).

- 7.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2013. (2013, accessed 31 December 2013).

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Minority Health. Cancer data/statistics. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=4. (2013, accessed 31 December 2013).

- 9.Womenshealth.gov. Breast cancer: frequently asked questions. http://www.womenshealth.gov/faq/breast-cancer.cfm. (2012, accessed 31 December 31 2013).

- 10.National Cancer Institute. Cancer Health Disparities. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/disparities/cancer-health-disparities. (2011, accessed 31 December 2013).

- 11.Susan G Komen Foundation. Facts for life. Racial & ethnic differences. http://ww5.komen.org/uploadedFiles/Content_Binaries/806-373a.pdf. (n.d., accessed 31 December 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, et al. Ethnicity and breast cancer: factors influencing differences in incidence and outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97(6):439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi JK, Swartz MD, Reyes-Gibby CC. English proficiency, symptoms, and quality of life in Vietnamese- and Chinese-American breast cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(1):83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim J, Yi J. The effects of religiosity, spirituality, and social support on quality of life: a comparison between Korean American and Korean breast and gynecologic cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(6):699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eysenbach G The impact of the Internet on cancer outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin 2003;53(6):356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tu S-P, Chen H, Chen A, Lim J, May S, Drescher C. Clinical trials: understanding and perceptions of female Chinese-American cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;104(12 Suppl):2999–3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashing-Giwa KT, Kagawa-Singer M, Padilla GV, et al. The impact of cervical cancer and dysplasia: a qualitative, multiethnic study. Psychooncology. 2004;13(10):709–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wellisch D, Kagawa-Singer M, Reid SL, Lin YJ, Nishikawa-Lee S, Wellisch M. An exploratory study of social support: a cross-cultural comparison of Chinese-, Japanese-, and Anglo-American breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 1999;8(3):207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieberman MA, Goldstein BA. Self-help on-line: an outcome evaluation of breast cancer bulletin boards. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(6):855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, Shaw BR, Seydel ER, van de Laar MAFJ. Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia. Qual Health Res 2008;18(3):405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Pingree S, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW, Bricker E, Pingree S, Chan CL. The use and impact of a computer-based support system for people living with AIDS and HIV infection. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Sic Med Care Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1994:604–608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houston TK, Cooper LA, Ford DE. Internet support groups for depression: a 1-year prospective cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159(12):2062–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieberman MA, Golant M, Giese-Davis J, et al. Electronic support groups for breast carcinoma: a clinical trial of effectiveness. Cancer. 2003;97(4):920–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McTavish FM, Gustafson DH, Owens BH, et al. CHESS (Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System): an interactive computer system for women with breast cancer piloted with an underserved population. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 1995;18(3):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin SD, Youngren KB. Help on the net: internet support groups for people dealing with cancer. Home Healthc Nurse. 2002;20(12):771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Høybye MT, Dalton SO, Deltour I, Bidstrup PE, Frederiksen K, Johansen C. Effect of Internet peer-support groups on psychosocial adjustment to cancer: a randomised study. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(9):1348–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiljer D, Urowitz S, Barbera L, et al. A qualitative study of an internet-based support group for women with sexual distress due to gynecologic cancer. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 2011;26(3):451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pautler SE, Tan JK, Dugas GR, et al. Use of the internet for self-education by patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57(2):230–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seale C, Ziebland S, Charteris-Black J. Gender, cancer experience and internet use: a comparative keyword analysis of interviews and online cancer support groups. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2006;62(10):2577–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Im E-O, Chee W, Lim H-J, Liu Y, Guevara E, Kim KS. Patients’ attitudes toward internet cancer support groups. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(3):705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Im E-O, Chee W, Tsai H-M, Lin L-C, Cheng C-Y. Internet cancer support groups: a feminist analysis. Cancer Nurs 2005;28(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(22):2618–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meleis AI, Lipson JG, Paul SM. Ethnicity and health among five Middle Eastern immigrant groups. Nurs Res 1992;41(2):98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Im E-O. The situation-specific theory of pain experience for Asian American cancer patients. Adv Nurs Sci 2008;31(4):319–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Im E-O, Liu Y, Kim YH, Chee W. Asian American cancer patients’ pain experience. Cancer Nurs 2008;31(3):E17–E23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Census Bureau. Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month: May 2011. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb11-ff06.html (2011, accessed 21 December 2013).

- 38.U.S. Census Bureau. The Asian Population 2010. 2010 Census Brief. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf. (2012, accessed 21 December 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller BA, Chu KC, Hankey BF, Ries LAG. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns among specific Asian and Pacific Islander populations in the U.S. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 2008;19(3):227–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Im E-O. Online support of patients and survivors of cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 2011;27(3):229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danaher BG, McKay HG, Seeley JR. The information architecture of behavior change websites. J Med Internet Res 2005;7(2):e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fowler M GUI Architectures. August 2010. http://www.martinfowler.com/eaaDev/uiArchs.html. (2010, accessed 20 May 2014).

- 43.Fuchs S, Minarik K. Rails Internationalization (I18n) API. http://guides.rubyonrails.org/i18n.html. (2010, accessed 20 May 2014).

- 44.Spector S New to Xen Guide. http://www.xen.org/files/Marketing/NewtoXenGuide.pdf. (2010, accessed 20 May 2014).

- 45.Weber RP. Basic Content Analysis. SAGE; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis JR. Sample sizes for usability tests: mostly math, not magic. interactions. 2006;13(6):29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wharton C, Rieman J, Lewis C, Polson P. The Cognitive Walkthrough Method: A Practitioner’s Guide In: Usability Inspection Methods. New York: Wiley; 1994:105–140. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav 2003;27 Suppl 3:S227–S232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods. Seventh Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinert C Measuring social support: PRQ2000 In: Measurement of Nursing Outcomes: Vol. 3. Self Care and Coping. New York: Springer; 2003:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Measuring social isolation among older adults using multiple indicators from the NSHAP study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64 Suppl 1:i38–i46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schofield P, Gough K, Lotfi-Jam K, Aranda S. Validation of the Supportive Care Needs Survey-short form 34 with a simplified response format in men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(10):1107–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mishel MH. The measurement of uncertainty in illness. Nurs Res 1981;30(5):258–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Merluzzi TV, Martinez Sanchez MA. Assessment of self-efficacy and coping with cancer: development and validation of the cancer behavior inventory. Health Psychol 1997;16(2):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M, Kasimis BS, Thaler HT. The memorial symptom assessment scale short form (MSAS-SF). Cancer. 2000;89(5):1162–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol 1997;15(3):974–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bouma G, Admiraal JM, de Vries EGE, Schröder CP, Walenkamp AME, Reyners AKL. Internet-based support programs to alleviate psychosocial and physical symptoms in cancer patients: a literature analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;95(1):26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu C-F, Tsai Y-C, Jang F-L. Patients’ Acceptance towards a Web-Based Personal Health Record System: An Empirical Study in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(10):5191–5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruland CM. A survey about the usefulness of computerized systems to support illness management in clinical practice. Int J Med Inf 2004;73(11–12):797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bullard MJ, Meurer DP, Colman I, Holroyd BR, Rowe BH. Supporting clinical practice at the bedside using wireless technology. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med 2004;11(11):1186–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoybye MT Storytelling of Breast Cancer in Cyberspace On-Line Counteractions to the Isolation and Demeaning of Illness Experience. University of Copenhagen, 69/2002 Science Shop Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Owen JE, Klapow JC, Roth DL, et al. Randomized pilot of a self-guided internet coping group for women with early-stage breast cancer. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med 2005;30(1):54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hong Y, Peña-Purcell NC, Ory MG. Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: a systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(3):288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]