Abstract

The aim of this systematic review was to synthesize the literature regarding health-related stigma in adolescents and adults living with sickle cell disease (SCD). Four domains were identified from 27 studies: 1) social consequences of stigma, 2) the effect of stigma on psychologicalwell-being, 3) the effect of stigma on physiological well-being, and 4) the impact of stigma on patient-provider relationships and care-seeking behaviors. Current literature revealed that SCD stigma has detrimental consequences. Methodological issues as well as research and practice implications were identified. Future research should further examine the impact of health-related stigma on self-management of SCD.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetically inherited disorder of the hemoglobin that can lead to serious health complications including infection, stroke, and acute and chronic pain. SCD affects 7 million people worldwide (Yawn et al., 2014). According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), in the United States (US), between 90,000 to 100,000 Americans are diagnosed with SCD and approximately 1 out of every 500 newborn Black infants is at risk for inheriting SCD (CDC, 2015). SCD is a major public health concern, with estimated healthcare costs for individuals amounting to millions of dollars annually and around 80.5% of cost being associated with hospital care (Kauf, Coates, Huazhi, Mody-Patel, & Hartzema, 2009). Comprehensive care is essential for avoiding hospitalizations and increasing quality of life in individuals with SCD, but unfortunately there is less access to comprehensive care for SCD than for other genetic disorders like cystic fibrosis and hemophilia (Grosse et al., 2009). The disparities in comprehensive care stemfrom fewer SCDdisease centers being available, SCD centers being utilized less, and gaps in both funding support for SCD and implementation of clinical advances (Grosse et al., 2009; Smith, Oyeku, Homer, & Zuckerman, 2006). The cause and perpetuation of these disparities are linked to the stigma that this population faces.

Stigma involves some type of labeling that leads to negative consequences for the stigmatized individuals (Link & Phelan, 2013). Goffman (1986) social theory of stigma defined it as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” (p. 4). Stigmatization due to health status is referred to as health-related stigma and involves devaluation, judgment, or social disqualification of individuals based on a health condition (Weiss, Ramakrishna, & Somma, 2006). According to Scambler (2009) sources of health-related stigma frequently include family members, the general public, and health care providers. Any of the stigma and stigma-related concepts defined in Table 1 could be a consequence of, or related to health-related stigma. Individuals with SCD face many obstacles to receiving care; but stigma is one of the most influential and ominous. People who have SCD may experience health-related stigma for a variety of reasons including race, disease status, socioeconomic status, delayed growth and puberty, and/or having chronic and acute pain that needs to be managed with opioids (Bediako & Moffitt, 2011; Bhatt-Poulose, James, Reid, Harrison, & Asnani, 2016; Haywood, Tanabe, Naik, Beach, & Lanzkron, 2013; Lazio et al., 2010; Penner et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Types of stigma and stigma-related concepts

| Terms | Publication(s) | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| TYPES OF STIGMA | ||

|

| ||

| Health-Related Stigma Disease Stigma |

(Adeyemo et al., 2015; M. Ezenwa et al., 2016; C. Jenerette et al., 2012; Wakefield et al., 2017) | The occurrence of labeling and stereotyping, negative treatment, and discrimination in the context of health-related situations. |

| Internalized Stigma | (Bediako et al., 2014; Holloway et al., 2016) | The act of adopting society’s negative labeling and views about having a disease. Can lead to negative person feeling and guilt about disease status. |

| Felt Stigma Perceived Stigma |

(Blake et al., 2017; Sankar et al., 2006) | The perception that one is being treated negatively as a target of stigma. Can occur even if the source of the treatment is ambiguous (attributional ambiguity). |

| Societal Stigma Social stigma |

(Mulchan et al., 2016) | Negative attitudes toward a person for a characteristic deemed undesirable by society |

| External Stigma | (C. Jenerette et al., 2012) | The awareness that there are negative attitudes from the general public, healthcare providers, or family/friends. |

| Enacted Stigma | (Blake et al., 2017) | The experience of negative treatment due to stigmatized status. |

| Anticipated stigma | (Bediako et al., 2014) | The expectation that one will be negatively stereotyped and treated in future encounters |

|

| ||

| STIGMA-RELATED CONCEPTS | ||

|

| ||

| Attributional ambiguity | Uncertainty regarding the source of negative treatment | |

| Social Exclusion | (Bediako et al., 2014) | The extent that disease status causes interpersonal rejection |

| Disclosure | (Bediako et al., 2014) | Considerations and apprehension about telling others about disease status. |

| Expected Discrimination | (Bediako et al., 2014) | Anticipated negative treatment due to disease status |

| Racial Health Disparity | (Wakefield et al., 2017) | Consists of differences in opportunities, access to healthcare, and care received |

| Perceived racial bias Perceived Racism |

(Cole, 2007; Royal et al., 2011; Wakefield et al., 2017) | Experiencing discrimination or negative treatment because of race. |

| Perceived Injustice | (Ezenwa et al., 2015) | Perception of unfair treatment |

| Healthcare Injustice | (M. O. Ezenwa et al., 2016) | Perception of unfair treatment from healthcare providers |

| Perceived Discrimination | (Haywood et al., 2014; Haywood et al., 2014; Mathur et al., 2016; Stanton et al., 2010) | Negative treatment perceived on the basis of race or ethnicity or disease status. |

While there are many sources of stigma experienced by persons with SCD, racism is an important source as most affected individuals in the US are Black. Despite SCD being a genetic disease, it is impacted by racism and health care equity issues, including hindered access to care and less funding support. Cystic fibrosis, a genetic disease that primarily affects individuals that are White and occurs in approximately 30,000 individuals in the US, is more than eight times more likely to receive funding than SCD despite there being far more people affected by SCD (Strouse, Lobner, Lanzkron, MHS, & Haywood, 2013). Racism frequently interacts and exacerbates other sources of health-related stigma in SCD, including disease and opioid based stigmas. Due to the complex juxtaposition of these concepts, racism is not only recognized as a source of stigma, but is also seen as akin to stigma.

Although health-related stigma plays a significant role in the lives of individuals living with SCD, there is currently no published synthesis in the literature. A systematic review can provide information on the current body of health-related SCD stigma literature, including gaps in the literature, that will lead to a more methodical approach as this area is studied further. This systematic reviewsynthesizes the primary empirical literature to address the question: What is the state of the knowledge regarding health-related stigma in adolescents and adults living with SCD? This paper 1) describes the methods of the review, 2) synthesizes and discusses the findings, and 3) identifies implications for research and clinical practice.

Methods

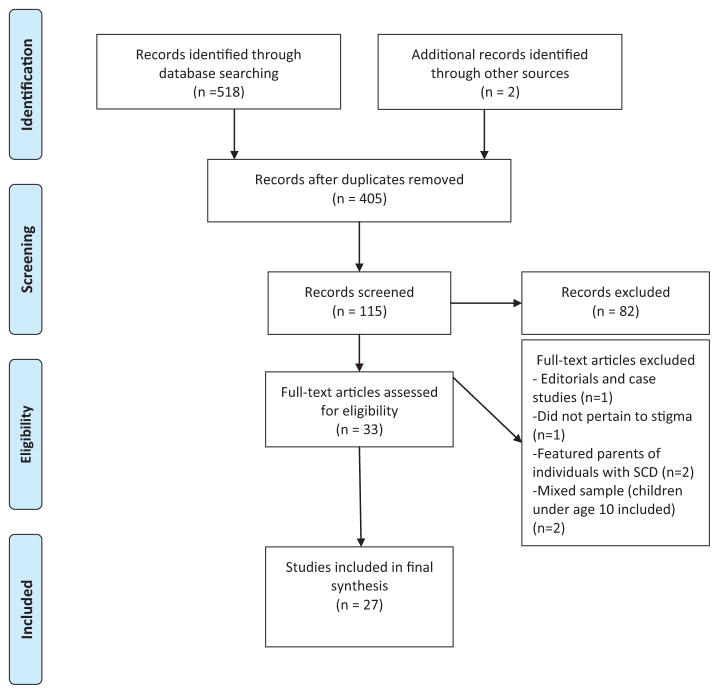

This review synthesizes the research literature on stigma of SCD in adolescents and adults with SCD identified from electronic searches of PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Medline, and SocINDEX. Peer-reviewed research studies were included if they were: (a) written in English and (b) provided adolescent (ages 10–19) and/or adult specific findings. Studies conducted in adolescents were included as previous studies suggest that individuals with SCD in adolescence have similar experiences and consequences of stigma as adults (i.e. greater disease burden and lower quality of life) (Adeyemo, Ojewunmi, Diaku-Akinwumi, Ayinde, & Akanmu, 2015; Wakefield et al., 2017). Adolescent populations are those that are within age limits of 10 to 19, the range that is consistent with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of adolescence (WHO, 2015). All genotypes of SCD were included. Exclusion criteria included editorials; case studies; and studies focusing on caregiver, parent, or healthcare provider perspectives. The key word “sickle cell” was searched in combination with “stigma”, “health-related stigma”, and previously identified surrogate terms for stigma including “discrimination”, “prejudice”, “injustice”, “devalued”, and “dehumanized”(Corrigan, 2004; Jacob, 2001; Maxwell, Streetly, & Bevan, 1999). The search also included hand searches of tables of reference lists of selected studies. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) depicts the results of the literature search including the number of studies reviewed at each stage and the reasons for exclusion of full text studies (Liberati et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Literature Search Flow Chart. Source: Adapted from PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram (Moher et al., 2009).

Findings

Sample

Twenty-seven peer-reviewed studies, published between 2004 and 2017 met the inclusion criteria for analysis. Most studies used descriptive designs (one was a randomized control trial); and authors were nurses, psychologists, hematologists, social workers, sociologists, geneticists, and bioethicists. Data were abstracted using Garrard (2013) matrix method and organized by main concepts, measures, samples, methods, main findings, and limitations. The matrix method uses a structured abstraction strategy to accomplish four fundamental tasks when reviewing literature: 1) deciding what documents to review, 2) comprehending the documents, 3) evaluating the documents, and 4) synthesizing the literature (Garrard, 2013, p. 6, 17–18). Table 2 summarizes the studies synthesized.

Table 2.

Synthesis of Articles

| Author/year | Purpose | Approach | Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adeyemo et al. (2015) | To assess health-related quality of life and perceived stigma in adolescents with SCD. | Location: Nigeria Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 80 adolescents ages 15–18 with SCD and a control group of 80 unaffected adolescents |

Adolescents with SCD (70%) reported moderate to very high stigma and stigma was negatively associated with all domains of health-related QoL. Adolescents with SCD had worse health-related QoL than their unaffected peers. |

| Bediako et al. (2014) | To test the Measure of Sickle Cell Stigma Scale (MoSCS). | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 262 adolescents and adults ages 15–70 |

The 11 items loaded on four factors: social exclusion, internalized stigma, disclosure concerns, and expected discrimination. Cronbach’s alpha for the entire scale was. 86. |

|

| |||

| Blake et al. (2017)) | To understand stigma and illness uncertainty experiences in adults with SCD. | Location: Jamaica Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 101 adults |

Stigma and illness uncertainty had a small but significant correlation. |

|

| |||

| Cobo Vde et al. (2013) | To describe and assess the development of sexuality in individuals with SCD. | Location: Brazil Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative and quantitative components Sample: 20 adults ages 19–47 |

In this mostly (75%) female sample, 65% said that they had impaired sexuality due to SCD. Participants reported their impairment being due to pain and discrimination and negative feelings experienced in intimate relationships. |

|

| |||

| Cole (2007) | To describe the chronic illness experience from the perspective of Black women with SCD, including disease related stress and mental health. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with qualitative components Setting: 10 women |

Themes that emerged from the interviews included stressful experiences during hospital care, stigmatizing experiences as result of their disease status, stressful events that precede pain episodes, and disease related stress impacting perceptions about mental health. |

|

| |||

| Derlega et al. (2014) | To describe the disclosure experiences of individuals with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Setting: 73 adults |

Participants disclosed their thoughts and feelings concerning pain episodes to God and to their primary medical providers than to both friends and family. Taking with God and parents about pain was associated with better psychological adjustment, including stigma consciousness. Participants who talked about pain episodes to parents were less self-conscious about being stigmatized or stereotyped because of their disease status. |

|

| |||

| Dyson et al. (2010) | To describe the disclosure patterns of children, adolescents, and young adults with SCD in school. | Location: UK Design: Cross-sectional using mixed method methodologies Sample: 569 questionnaires and 40 interviews; ages 4–25 |

Over 75% of the sample reported at least one negative experience at school (i.e. called lazy, prevented from drinking water). Participants that reported that more adults and peers knew about their disease status reported more negative experiences. Participants described a cost benefit analysis of whether or not they should disclose their disease status in school. |

|

| |||

| Ezenwa et al. (2015) | To examine the associations between perceived injustice, stress, and pain in adults with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional correlational pilot study Sample: 52 adults |

Perceived injustice from doctors and nurses was a significant predictor of perceived stress and pain. |

|

| |||

| Ezenwa et al. (2016) | To examine the pain coping strategies of individuals with SCD that experience healthcare injustice when seeking care. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional comparative study Sample: 52 adults |

Participants who reported healthcare injustice from physicians and nurses were more likely to use pain coping strategies associated with negative pain outcomes (catastrophizing, isolation, fear self-statements), while those reporting healthcare justice were more likely to use strategies associated with positive pain outcomes (hoping/praying, massage, calming self-statements). |

|

| |||

| Haywood et al. (2014) | To examine perceived discrimination in healthcare and pain burden among individuals with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 291 participants ages 15 and older |

Discrimination was associated with greater emergency room utilization, having difficulty persuading providers about pain, and experiencing daily chronic pain. Disease and not raced-based discrimination was associated with greater self-reported pain. |

| Haywood et al. (2014)) | To evaluate the association between perceived discrimination from healthcare providers and nonadherence to physician recommendations among individuals with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 273 participants ages 15 and older |

58% of the non-adherent group, compared to 43% of the adherent group, reported at least one experience of discrimination. The non-adherent group also reported significantly lower levels of trust of healthcare providers than did the adherent group” Individuals that had experienced previous discrimination were 53% likely to report nonadherence |

|

| |||

| Haywood et al. (2013) | To determine whether SCD patients have longer wait times to see physicians in the ED compared to a Long Bone Fracture (LBF) patient group and the General Patient Sample group. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 171,789 records used from a national database |

SCD patients waited 8% longer compared to general patient sample and 32% longer compared to LBF patients, after controlling for differences. Mean wait times were 50% longer for Black LBF patients. |

|

| |||

| Holloway et al. (2016) | To investigate internalized stigma amongst individuals with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 69 adults |

Participants reported low depressive symptoms and internalized stigma. Depressive symptoms and internalized stigma were positively related. |

|

| |||

| Jenerette et al. (2012) | To test the Sickle Cell Disease Health-Related Stigma Scale (SCD-HRSS) in young adults with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 77 adults ages 18–35 |

Preliminary analysis of the SCD-HRSS revealed Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for the entire scale (0.84) as well as for each of the subscales (Doctors = 0.68, Family = 0.82, Public = 0.73). |

|

| |||

| Jenerette et al. (2014). | To identify factors that influence care-seeking for pain in young adults with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional mixed methods pilot study Sample: 69 young adults ages 18–35 |

Participants waited until their pain was an average of 8.7 out of 10 before seeking care. The second most common reason for not seeking care was a desire to avoid the emergency departments due to prior treatment. |

|

| |||

| Jenerette et al. (2014) | To assess the efficacy of a self-care management intervention to lower self-perceived health-related stigma for young adults with SCD. | Location: US Design: Longitudinal, randomized control trial with quantitative components Sample: 90 adults with SCD ages 18–35 randomized into a Care-Seeking intervention or attention control group |

The care seeking intervention was associated with significant increase in perceived total stigma and stigma from doctors. |

|

| |||

| Kass et al. (2004) | To determine if genetic cause of disease influences experiences of privacy, disclosure, and consequences of disclosure experiences. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative and qualitative components Sample: 99 adults with SCD; comparison groups had cystic fibrosis, diabetes, HIV, and risks for breast or colon cancer |

Participants with SCD were very likely to: 1) regret others found about their disease status; 2) have individuals that they hope do not find out; 3) regret others found out; 4) to report discrimination experiences with employment and receiving healthcare as a result of their disease status. The main reason they regretted others knowing was because they may be treated differently (pitied, discriminated against stigmatized, etc.) as a result of others knowing. |

|

| |||

| Labore et al. (2017) | To explore transition to self-management in SCD in young adults. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with qualitative components Sample: 12 participants ages 21–25 |

All participants mentioned experiences or anticipation of stigma in adult care settings as a part of their transition experience. |

| Labrousse (2007) | To explore how young Haitian American women cope with having SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with qualitative components Sample: 12 participants ages 21–31) Participants described experiences of racial, socioeconomic, and medical unfairness in their life narratives. |

Participants described fearing seeking emergency room care due to anticipated stigma. |

|

| |||

| Mathur et al. (2016)) | To examine the relationship between perceived discrimination and both clinical and laboratory pain. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 71 adults |

Participants that reported discrimination in healthcare settings (38%) had greater clinical pain severity and functional pain interference. |

|

| |||

| Mulchan et al. (2016) | To examine the applicability of the Social-ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness to Transition (SMART) model for adolescents and young adults with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with qualitative and quantitative components Sample: 14 adolescents and young adults ages 14–24; 10 clinical experts |

During interviews, both individuals with SCD and providers identified stigma and lack of community awareness of SCD emerged as a theme within the SMART framework. Elements of stigma and racism also emerged in themes related to medical status and patient-provider communications. |

|

| |||

| Nelson & Hackman (2013) | To explore perceptions of race and racism among persons with SCD and their families and healthcare staff. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 112 patients/families, ages 12–50; 135 staff members |

Patients and their family members were more likely to report that race affects the quality of healthcare for individuals with SCD (50%) in comparison to healthcare providers (31.6%). While healthcare staff were more likely to report unfair treatment of SCD patients (20.9% vs. 10.9%). |

|

| |||

| Ola et al. (2016) | To explore experiences with depression in people living with SCD in Lagos, Nigeria. | Location: Nigeria Design: Cross-sectional using mixed method methodologies Sample: 103 completed questionnaires, ages 16–50; 15 interviewed and 10 completed focus groups |

74 participants had some level of depression ranging from mild to severe. In interviews, participants reported experiencing stigma in the community, workplace, and school and also in healthcare settings. Some participants reported risk-taking behaviors, suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts. During the focus groups, participants discussed challenges and ways to overcome living with SCD in a discriminatory society. |

|

| |||

| Royal et al. (2011) | To examine the relationship between race, identity, and experience of living with SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with qualitative and quantitative components Sample: 46 adults ages 18–59 |

Participants agreed with statements stating that their disease status affects how they are treated and that their race influences their experience with their disease. During interviews, participants described being treated differently due to their race and disease status in public and healthcare realms. 36% reported that their race did not impact their disease experience and 27% reported that their disease status had no effect on how they are treated. |

|

| |||

| Sankar et al. (2006) | To explore the relationship between genetic cause and stigma. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with qualitative components Sample: 22 adults with SCD ages 18–53; groups with cystic fibrosis, hearing loss/deafness, and breast cancer |

Overall genetic cause did not automatically lead to perceptions of stigma. Participants with SCD associated their condition with their racial identity and discrimination; whereas participants with cystic fibrosis rarely associated their disease with their race. |

|

| |||

| Stanton et al. (2010) | To explore the association between optimism, perceived discrimination, and healthcare utilization in SCD. | Location: US Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 49 adults |

There was an increase in hospitalizations among those with high optimism and a decrease among those with low optimism as perceived discrimination increased. There was also an increase in days hospitalized as perceived discrimination increased amongst those with high optimism and a decrease in those with low optimism. |

| Wakefield et al. (2017) | To determine the frequency of perceived racial bias and health-related stigma and how they are related to psychological and physical wellbeing in adolescents and young adults with SCD. | Location: Design: Cross-sectional with quantitative components Sample: 28 adolescents and young adults ages 13–21 |

All participants except 1 reported at least one experience of racial bias and perceived health-related stigma (both 96.4%). Perceived health-related stigma was positively correlated with perceived racial bias. Participants that reported less racial bias had higher quality of life. Participants that reported greater stigma had lower quality of life. There was a moderate positive relationship between perceived racial bias and pain burden. |

Four domains were identified from 27 studies: 1) the social consequences of stigma, 2) the effect of stigma on psychological well-being, 3) the effect of stigma on physiological well-being, and 4) the impact of stigma on patient-provider relationships and care-seeking behaviors. The four domains provided insight into the state of the literature regarding stigma of SCD and the impact that it has on the lives of individuals with SCD. However, due to the complexity of human experiences and disease processes, the consequences of stigma of SCD often simultaneously affect multiple domains. Additionally, the studies included conceptualized the consequences of stigma differently and a single study can have information applicable tomore than one domain.

Measures of stigma in SCD

Of the 27 studies reviewed, five used scales adapted for stigma of SCD (Bediako et al., 2014; Blake et al., 2017; Holloway, McGill, & Bediako, 2016; Jenerette, Brewer, Crandell, & I. Ataga, 2012; Jenerette, Brewer, Edwards, Mishel, & Gil, 2014). The remainder did not include a scale, adapted a scale about stigma or a stigma-related concept fromanother population, or interviewed participants about stigma and stigma-related concepts. Blake et al. (2017) utilized a SCD stigma scale that has not yet been published and the other 4 studies utilized either the Measure of Sickle Cell Stigma or the SCD Health-Related Stigma Scale.

Stigma of SCD is a multidimensional construct and the two tools developed to measure it reflect the multiple dimensions that comprise stigma (Bresnahan & Zhuang, 2011). Jenerette et al. (2012) developed the Sickle Cell Disease Health-Related Stigma Scale (SCD-HRSS) by modifying the Chronic Pain Stigma Scale (Reed, 2005). The SCD-HRSS has 40 items and 4 subscalesmeasuring health-related stigma fromdoctors, nurses, family, and the general public. The total SCD-HRSS has a Cronbach’s alpha reliability score of 0.84 and scores range 0.68–0.82 for subscales. Bediako et al. (2014) critiqued the SCD-HRSS and asserted that while the SCD-HRSS addresses public and external stigma perceived by individuals with SCD, there is no scale to address the interpersonal components of stigma, including internalized, anticipated, and self-stigmas. They developed the Measure of Sickle Cell Stigma (MoSCS), to address this gap in the measurement of SCD stigma. The MoSCS was developed using a scale developed to address HIV stigma (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001). TheMoSCS has 11 items and 4 subscales assessing internalized stigma, social exclusion, disclosure concerns, and expected discrimination. The total MoSCS scale has a Cronbach’s alpha reliability of 0.87 and scores range 0.74–0.89 for subscales.

Domains

The review of literature revealed four domains. Thedomains are defined in Table 3 and each are described below. In some cases a study’s findings supported more than one domain as the impact of stigma in one area does not preclude its impact in another.

Table 3.

Domains

| Domain | Definition |

|---|---|

| Social Consequences of Stigma | Summarizes evidence on the effects of stigma on social interactions, activities, and status |

| Effects of Stigma on PsychologicalWell-Being | Summarizes the influence that stigma has on mental health and quality of life, as well as the role stress plays in influencing psychosocial welfare. |

| Effects of Stigma on PhysiologicalWell-Being | Summarizes the direct (ie exacerbated pain due to stigma) and indirect (ie delayed care in the emergency department) influence that stigma has on the physical health of individuals with SCD |

| Impacts of Stigma on Patient-Provider Relationships and Care-Seeking Behaviors | Summarizes the influence of stigma on interactions between patients and providers and decisions that individuals with SCD about seeking care |

Domain 1: Social consequences of stigma

Eight studies contained findings regarding social stigma enacted from the general public and family/friends as well as disadvantageous social consequences of stigma. Individuals with SCD reported experiencing negative reactions from family/friends, co-workers, peers, and community members regarding their SCD status (Ola, Yates, & Dyson, 2016). The general public is often not educated about SCD and form their own, typically negative, opinions about people with SCD as a result (Royal, Jonassaint, Jonassaint, & De Castro, 2011; Sankar, Cho, Wolpe, & Schairer, 2006). This results in people with SCD being devalued and experiencing status loss. They also have their pain experiences discredited by others and are accused of being weak, lazy, or pretending to be ill (Ola et al., 2016; Royal et al., 2011). People with SCD reported being treated as if they have a physical or cognitive impairment that will make them incapable of achieving goals and life milestones (Royal et al., 2011). They also reported stigmatizing experiences in intimate relationships, due to SCD complications, such as pain, priapism, and delayed puberty, impairing their sexuality (Cobo Vde, Chapadeiro, Ribeiro, Moraes-Souza, & Martins, 2013; Cole, 2007).

A variety of disclosure concerns associated with revealing SCD status to others emanate from the social stigma felt by individuals with SCD; and thus they are often private about their disease status and regret telling others when they do reveal their status. Reported reasons for disclosure concerns include fear of being treated differently, either pitied or discriminated against. People with SCD also reported discrimination experiences with employment and receiving healthcare as a result of revealing their disease status (Cole, 2007; Dyson et al., 2010; Kass et al., 2004). They may choose not to disclose their disease status to avoid the anxiety of anticipated stigma and the attributional ambiguity associated with not knowing whether the treatment they are receiving is the result of stigma. Social stigma can severely impact ability to obtain resources and lead to racial, socioeconomic, and medical unfairness (Cole, 2007; Labrousse, 2007; Ola et al., 2016).

Domain 2: Effects of stigma on psychological well-being

Stigmatizing social experiences can lead to harmful effects on psychological well-being including internalized stigma, social isolation, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Labrousse, 2007; Ola et al., 2016). Nine studies described findings related to the negative effects stigma has on the quality of life, mental health, and psychological wellbeing of individuals with SCD. Adolescents with SCD (>13 years old) reporting high levels of perceived racial bias and stigma in both health-related and community contexts also hadworsened quality of life (Adeyemo et al., 2015; Wakefield et al., 2017). Stigma can impact physical functioning, daily roles, general health perception, and social function (Adeyemo et al., 2015).

Stigma also influences stress levels among individuals with SCD who reported stressful experiences during hospital care, including being stigmatized as drug seeking, delayed care in the emergency department, and healthcare providers doubting their reports of pain (Cole, 2007). Although stress can have physiological and psychological effects, stress is included in domain 2 because the studies summarized primarily focused on the psychological nature of stress. Perceived injustice from healthcare providers was a significant predictor of stress in individuals with SCD (Ezenwa, Molokie, Wilkie, Suarez, & Yao, 2015). Stress can also occur during their daily lives due to stigmatizing experiences, including underestimation by teachers or losing their jobs due to their SCD status (Cole, 2007). An additional daily stressor for individuals with SCD is the illness uncertainty experienced regarding pain crises and unforeseen complications. A study conducted by Blake et al. (2017) revealed that illness uncertainty and stigma share a small but significant correlation.

Due to the stress associated with revealing disease and health status, individuals tended to be selective when disclosing; in some situations this can be disadvantageous. Derlega et al. found that individuals that talk to God or family/friends about their SCD pain had positive psychological adjustment and were more likely to seek care and also had lower awareness of disease stigma or being stereotyped (Derlega et al., 2014). These findings underscore the importance of strong support in improving both psychological and physical wellbeing in individuals with SCD. The stress associated with stigmatization negatively impacts the mental health of individuals with SCD (Cole, 2007; Derlega et al., 2014). They are at risk for internalized stigma. Depressive symptoms, including feeling hopeless and loss of interest in daily activities, have been positively associated with internalized stigma in people with SCD (Holloway et al., 2016). Additionally, individuals who experience high rates of stigma are more likely to report anxiety, depressive symptomatology, stress, and anger in comparison to those reporting low rates of stigma (M. Ezenwa et al., 2016; Mathur et al., 2016).

Domain 3: Effects of stigma on physiologicalwell-being

Ten studies described the impact of stigma on physiological well-being. Individuals with SCD reported being stigmatized as drug seeking or drug addicts and having their experiences of pain discredited by healthcare providers (Labrousse, 2007; Mathur et al., 2016; Mulchan, Valenzuela, Crosby, & Sang, 2016). They experienced inadequate pain management and long wait times in the emergency department that correlated with their disease status and race (Haywood et al., 2013; Labore, Mawn, Dixon, & Andemariam, 2017). Haywood et al. (2013) illuminated the systematic nature of long wait emergency department wait times for SCD, despite the high triage priority rating of vaso-occlusive crises. Individuals with SCD waited 25% longer than the general population and 50%longer than thosewith long bone fractures after considering race and triage priority. Individuals with SCD adapted their behaviors to cope with anticipated stigma. Delayed care seeking and maladaptive pain coping strategies are related to experiences of stigma (Jenerette, Brewer, & Ataga, 2014; Labore et al., 2017). Ezenwa et al. found that individuals perceiving healthcare injustice from physicians and nurses were more likely to cope with their pain using maladaptive mechanisms, such as pain catastrophizing and isolation; while those who experienced healthcare justice coped with their pain using prayer, calming, attention diversion, and increased behavioral activity (Ezenwa et al., 2015). The maladaptive behaviors that form as a result of stigma can severely impact both physiological and psychological health status in SCD.

Stigmahas been found to exacerbate the pain that people with SCD experience as a result of their disease pathology. People with SCD that reported experiencing higher rates of disease and race-based discrimination in healthcare settings also reported greater pain, pain severity, pain burden, and pain interference with functionality, sleep, and daily activities (Haywood et al., 2014; Mathur et al., 2016; Wakefield et al., 2017). Finally, the effects of stigma on mental health can also impact physiological wellbeing in the form of self-harming behaviors and suicide (Ola et al., 2016). This underscores the simultaneous effect that stigma has on physiological and psychological wellbeing.

Domain 4: Impacts of stigma on patient-provider relationships and care-seeking behaviors

Eleven studies contained results pertaining to how stigma stemming from healthcare settings and providers influenced care-seeking behaviors and patient-provider relationships. Individuals with SCD reported that race and disease based discrimination impacts the healthcare they receive (Mulchan et al., 2016; Nelson & Hackman, 2013; Royal et al., 2011). Those that have experiences with discrimination were more likely to be non-adherent to medical recommendations and reported low levels of trust in healthcare providers (Haywood et al., 2014). Additionally, people with SCD often identified a lack of awareness and education surrounding SCD in the healthcare provider community as a contributor to the stigma they experience (Cole, 2007).

Stanton et al. (2010) illuminated how the presence of stigma makes it difficult to improve patient-provider relationships by assessing the relationships between perceived discrimination and optimism (the expectation that good things will happen). They found that individuals that had high discrimination experiences and optimism, had an increase in hospitalizations in comparison to those with high discrimination experiences and low optimism (Stanton et al., 2010). Having a pessimistic outlook towards healthcare systems and providers may be more protective in terms of health outcomes; however pessimistic outlooks toward healthcare systems can further hinder patient-provider relationships. Furthermore, strained patient-provider relationships can result in hindered care-seeking behaviors.

Individuals with SCD also alter their care-seeking behaviors based on their experiences with stigma. Young adults with SCD (ages 21–25) reported experiencing lack of empathy from healthcare providers regarding their pain, long wait times in the emergency department, inadequate pain management in the emergency department, and anticipated stigma when seeking care for pain. One qualitative study illustrated this stigma in an example: if an asthmatic patient knows the specific amount of prednisone they need for treatment they will be commended by the healthcare community, while a SCD patient in a pain crisis will be labeled as drug seeking if they are able to vocalize the type and dosage of opioids they need (Mulchan et al., 2016). Individuals with SCD reported adjusting their care seeking behaviors by treating their pain at home and/or waiting until pain becomes unbearable before seeking care for their pain, as a result of stigmatizing experiences (Labore et al., 2017). Jenerette et al. (2014) found that 88% of young adults with SCD wait until their pain is an average of 8.7 on a scale of 1–10 before seeking care and factors that influence this decision included anticipated stigma.

The impact of stigma on patient-provider relationships creates challenges when developing interventions to decrease stigma and improve health outcomes in SCD. Jenerette et al. (2014) conducted a pilot study to test an intervention to decrease stigma in young adults with SCD based on the Theory of Self-Care Management of SCD (Jenerette & Murdaugh, 2008). The intervention focused on prompt cue recognition and early care seeking. The study used a randomized control trial method with an intervention group and attention control group (participants in this group participated in activities that imitated the time and attention provided by the intervention) in a population of 90 young adults with SCD ages 18–35. The treatment group was found to increase awareness of stigma, rather than decrease perceptions of stigma (Jenerette et al., 2014). This is the only intervention study that has attempted to decrease stigma and improve care-seeking behaviors amongst individuals with SCD. This pilot study had a high attrition rate which could have influenced results. Although important lessons were learned in this pilot, results support the insidious and complex nature of health-related stigma in SCD.

Discussion

This systematic review examined the empirical literature on SCD-related stigma in adults and adolescents with SCD. Twenty-seven descriptive studies and one intervention study were reviewed. Overall the review demonstrates the impact that stigma has on the lives and health of individuals with SCD, including hindering physiological and psychological wellbeing, having harmful social consequences, and impairing healthcare interactions. Methodological issues amongst the studies and gaps in the literature were identified. Additionally, practice implications for nurses and limitations of the study itself were noted.

Methodological issues

There are several methodological issues that create gaps in the current understanding of SCD stigma. Firstly, all studies assessing perceived stigma in SCD were descriptive and cross-sectional, except one longitudinal, randomized control trial (Jenerette et al., 2014). There is limited knowledge about the causal relationships stigma has and how to decrease stigma. Additionally, studies describing perceived stigma were mainly quantitative with few mixed methods and qualitative explorations the meaning of the stigmatizing experiences. More qualitative explorative studies that describe the experiences of individuals with SCD are needed to fully understand the nuanced and layered stigma that individuals with SCD experience. Additionally, grounded theory designs may be useful to further the conceptual understanding of the components of stigma and their relationship, and thus contribute to theory development. An improved theorized concept of SCD stigma may lead to the development of useful interventions in this population. The literature of stigma in SCD could benefit from longitudinal studies tracking stigma across time and in depth qualitative and mixed methods explorations of stigma and related concepts. Finally, exploring SCD stigma using structural equation modeling could potentially identify latent variables and reveal not yet explored variable relationships effecting intra- and interpersonal aspects of SCD stigma. Longitudinal, mixed-method, qualitative studies, and structural equation modeling could illuminate the mechanisms through which stigma operates and impacts the wellbeing of individuals with SCD; thus, leading to the development of successful interventions to decrease stigma.

Another methodological issue that limits the current understanding of stigma of SCD is the systematic exclusion of individuals who do not have access to comprehensive SCD care. Studies assessing perceived stigma primarily recruited participants from academic SCD centers. This creates a significant gap in understanding and limits the generalizability of the studies, as individuals who do not have access to comprehensive care centers may be more vulnerable to stigma. For instance, these individuals may have fewer options for healthcare due to socioeconomic status or have more encounters with healthcare providers that are not educated about SCD. In order to develop a complete understanding of SCD stigma individuals outside of comprehensive care settings need to be studied.

The literature of stigma and SCD could also benefit from the use of conceptual frameworks that assist in understanding the interaction between the social determinants of health. Intersectionality theory asserts that experiences with discrimination and injustice are distinct depending characteristics including race, class, age, and gender (Winker & Degele, 2011). Understanding how different aspects of individuals’ identities intersect has the potential to reveal the intricacies of the processes that cause health inequities (Bauer, 2014). While Cobo et al. describes how stigma in intimate partner relationships differs depending on gender, there are amultitude of other ways experiences of stigma can vary depending on clinical and demographic characteristics. Studying these intersections will provide a more complete understanding of stigma of SCD; and advance knowledge of how different individuals experience and cope with stigma. Coping with the stigma of SCD can lead to both positive and negative adaptive efforts. Identifying these efforts were not a part of the search strategy; however, this review supports the importance of coping while living with a life-long chronic condition, and its relevance to both researchers and clinicians. In summary, severalmethodological gaps in the literature were identified: (1) mixed-method and qualitative studies that describe the stigma experiences of individuals with SCD, (2) longitudinal studies that describe the effect stigma has on the trajectory of SCD, (3) structural equation modeling designed to uncover latent variables and unexplored relationships affecting SCD stigma, (4) interventions aimed to decrease stigma, (5) sampling methods that include individuals who do not have access to comprehensive SCD care, and (6) studies exploring intersectional identities in SCD. Addressing methodological gaps in the literature can lead to a more complete understanding of stigma of SCD.

Research implications

Several gaps have been identified that require further research to improve the understanding of stigma of SCD. First, the compounded or layered nature of stigma makes it difficult to precisely pinpoint the influence of stigma on the lives of individuals with SCD. Many of the studies conflated racism and stigma. Royal et al. (2011) attempted to uncover the role that race plays in SCD stigma; one participant in this study noted, “My race does influence my experience with SCD because blacks are viewed in a negative light. Racism is an added burden to my experience as a person with SCD” (p. 397). Additionally, Haywood et al. (2013) were able to unearth data confirming that both race and disease status contribute to longer wait times for individuals with SCD. However, this is the extent of the literature of layered stigma in SCD; studying layered stigma using intersectionality theory could address this gap in the literature.

Studying layered stigma from a global perspective can also contribute to our understanding of stigma of SCD. Layered stigma in SCD is a significant barrier in the health and overall wellbeing of individuals with SCD. Studies designed to improve our understanding of stigma’s impact on intersectional identities can improve our understanding how racism and health-related and disease stigma function together. For instance, while racial stigma might not manifest as abundantly as it does in theUnited States and United Kingdom, colorism is a global phenomenon. There are currently no publications addressing how colorism influences SCD stigma and health outcomes. Publications in Nigeria, Brazil, England, and the United States have revealed that disease stigma manifests and operates similarly regardless of country (Adeyemo et al., 2015; Cobo Vde et al., 2013; Dyson et al., 2010; Ola et al., 2016), however racial stigma may manifest differently in countries where Black people are the majority. Studying SCD stigma globally would increase our understanding of how layered stigma operates and also provide opportunities to address reducing SCD stigma and improving health outcomes worldwide.

The study of how institutionalized stigma contributes to health inequities in SCD is also relatively unaddressed in SCD stigma literature. While there are publications acknowledging health inequity and disparity in SCD (Grosse et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2006), more exploration of how structural discrimination can contribute to poor wellbeing and health outcomes in individuals with SCD is needed. Understanding how stigma functions outside of personal and interpersonal domains is important, as institutionalized or structural stigma can impact the daily lives, coping behaviors, self-management strategies, and overall wellbeing of individuals with SCD as well.

There is also a limited understanding of internalized stigma. The majority of SCD literature focuses on perceived stigma in SCD and its effects on patient-provider relationships, care-seeking behaviors, and the mental and physical wellbeing of individuals with SCD. However, the impact of internalized stigma also needs to be assessed, as Holloway et al. (2016) found a positive relationship between internalized stigma and depressive symptoms. Additionally, SCD stigma often goes unrecognized, unaddressed, and is not measured in studies assessing psychological wellbeing in SCD, despite all of the literature confirming that stigma is associated with poor psychological outcomes. Learning more about internalized stigma and its influence on mental health, coping with pain, and disease management is necessary to develop a more complete understanding of SCD.

Although there are several sources of SCD stigma, current literature tends to focus primarily on stigma from healthcare providers. Encounters with healthcare providers and systems is only one aspect of individuals with SCD lives. More studies are needed that assess the stigma that individuals with SCD experience fromtheir family and friends. In diabetes literature, stigma from the general public can cause individuals not to perform self-management behaviors and this can lead to worsened health outcomes (Tak-Ying Shiu, Kwan, & Wong, 2003). A more comprehensive view of how sources of stigma impact the lives of individuals with SCD is needed to strengthen understandings of SCD stigma.

The literature addresses how SCD stigma impacts care-seeking behavior, while other self-management behaviors such as stress management and medication adherence are less frequently addressed. Grasping the link between stigma and self-management in SCD is crucial as this knowledge can be used to develop interventions to improve quality of life and health outcomes in SCD (Matthie, Hamilton, Wells, & Jenerette, 2015; Matthie, Jenerette, & McMillan, 2015). The Theory of Self-Care Management of Sickle Cell Disease can be used to inform future interventions focusing on health-related stigma as an outcome and studies seeking to explore the relationship between stigma and SCD (Jenerette & Murdaugh, 2008).

Finally, exploring the link between chronic stress and stigma could reveal key information about the impact that stigma has on physiological and psychological wellbeing. Both self-reported measures and physiological markers of stress should be studied. In obesity and stigma literature, exposure to stigma was found to increase cortisol levels, thus increasing potentially harmful physiological consequences of stigma on wellbeing (Schvey, Puhl, & Brownell, 2014). Other factors that may mediate the relationship between stigma and wellbeing that are inadequately explored in SCD literature include coping mechanisms, disease self-management, and social support. Having social support influences response to stigma, coping mechanisms, and disease self-management strategies (Scambler, 2009). Understanding these mediating factors could contribute to a better understanding of stigma of SCD and ways to reduce it.

Practice implications

Nurses can decrease stigma bymaking themselves aware of their own biases and educating themselves as well as other healthcare professionals about appropriate ways to interact with and care for individuals with SCD. Despite, its potential to affect social functioning, physiological and psychological wellbeing, and health outcomes in SCD, stigma often goes unrecognized and its affects are unassessed. Nurses can also decrease the effects of stigma by recognizing stigma and employing interventions to decrease or treat the effects of stigma, such as assessing for mental healthcare needs and addressing challenges related to support.

Limitations

This review has limitations. Studies written in other languages were excluded, which limits the generalizability of the findings to non-English speaking populations of individuals with SCD. Additionally, there is the potential for error because a single reviewer performed the search and developed the matrices.

Conclusion

Stigma of SCD is a pressing health concern. Factors that contribute to stigma in SCD include disease status, pain and opioid use, racism, disease severity, and sociodemographic characteristics. Stigma can stem from sources including institutions, healthcare providers, general public, and family and friends. Current literature surrounding stigma in SCD reveals that stigma has detrimental consequences for individuals with SCD, including having negative social consequences, impairing healthcare interactions, and hindering physiological and psychosocial wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

I am in gratitude to Drs. Coretta Jenerette and Paula Tanabe for their guidance, support, and attentiveness throughout the development of this manuscript.

Funding

The first author received by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Research Service Award, 1F31NR017344-01 and the Jonas Nurse Leaders Scholar Program.

Footnotes

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/imhn.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

We certify that there is no conflict of interest with any organizations regarding the material discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Adeyemo TA, Ojewunmi OO, Diaku-Akinwumi IN, Ayinde OC, Akanmu AS. Health related quality of life and perception of stigmatisation in adolescents living with sickle cell disease in Nigeria: A cross sectional study. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2015;62(7):1245–1251. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;110:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bediako SM, Lanzkron S, Diener-West M, Onojobi G, Beach MC, Haywood C., Jr The Measure of Sickle Cell Stigma: Initial findings fromthe Improving Patient Outcomes through Respect and Trust study. Journal of Health Psychology. 2014;21(2):808–820. doi: 10.1177/1359105314539530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bediako SM, Moffitt KR. Race and social attitudes about sickle cell disease. Ethnicity & Health. 2011;16(4–5):423–429. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.552712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt-Poulose K, James K, Reid M, Harrison A, Asnani M. Increased rates of body dissatisfaction, depressive symptoms, and suicide attempts in Jamaican teens with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(12):2159–2166. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake A, Asnani V, Leger RR, Harris J, Odesina V, Knight-Madden J, … Asnani MR. Stigma and illness uncertainty: Adding to the burden of sickle cell disease. Hematology. 2017;23(2):122–130. doi: 10.1080/10245332.2017.1359898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan M, Zhuang J. Exploration and validation of the dimensions of stigma. Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(3):421–429. doi: 10.1177/1359105310382583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Sickle Cell Disease: Data and Statistics. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html.

- de Cobo VA, Chapadeiro CA, Ribeiro JB, Moraes-Souza H, Martins PR. Sexuality and sickle cell anemia. Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia. 2013;35(2):89–93. doi: 10.5581/1516-8484.20130027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PL. Black women and sickle cell disease: Implications for mental health disparities research. Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2007;5(4):24–39. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=105172329&site=ehost-live. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist. 2004;59(7):614. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Janda LH, Miranda J, Chen IA, Goodman BM, III, Smith W. How patients’ self-disclosure about sickle cell pain episodes to significant others relates to living with sickle cell disease. Pain Medicine. 2014;15(9):1496–1507. doi: 10.1111/pme.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson SM, Atkin K, Culley LA, Dyson SE, Evans H, Rowley DT. Disclosure and sickle cell disorder: A mixed methods study of the young person with sickle cell at school. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(12):2036–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.010. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953610002376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa M, Yao Y, Molokie R, Wang Z, Suarez M, Zhao Z, … Wilkie D. The association of sickle cell-related stigma with physical and emotional symptoms in patients with sickle cell pain. J Pain. 2016;17(4s):S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.01.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa MO, Molokie RE, Wilkie DJ, Suarez ML, Yao Y. Perceived injustice predicts stress and pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Management Nursing. 2015;16(3):294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard J. Health sciences literature review made easy. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc, New York; 1986. (Reissue Edition) [Google Scholar]

- Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Strickland B, Trevathan E. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):407–412. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood C, Jr, Lanzkron S, Bediako S, Strouse JJ, Haythornthwaite J, Carroll CP, … Beach MC. Perceived discrimination, patient trust, and adherence to medical recommendations among persons with sickle cell disease. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29(12):1657–1662. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2986-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood C, Jr, Tanabe P, Naik R, Beach MC, Lanzkron S. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2013;31(4):651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood C, Diener-West M, Strouse J, Carroll CP, Bediako S, Lanzkron S, … Haywood C., Jr Perceived discrimination in health care is associated with a greater burden of pain in sickle cell disease. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2014;48(5):934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway BM, McGill LS, Bediako SM. Depressive Symptoms and Sickle Cell Pain: TheModerating Role of Internalized Stigma. Stigma Health. 2016;2(4):271–280. doi: 10.1037/sah0000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob E. The pain experience of patients with sickle cell anemia. PainManagement Nursing. 2001;2(3):74–83. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2001.26119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenerette C, Brewer CA, Crandell J, Ataga IKI. Preliminary validity and reliability of the Sickle Cell Disease Health-Related Stigma Scale. Issues In Mental Health Nursing. 2012;33(6):363–369. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.656823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenerette CM, Brewer CA, Ataga KI. Care seeking for pain in young adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Management Nursing. 2014;15(1):324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenerette CM, Brewer CA, Edwards LJ, Mishel MH, Gil KM. An intervention to decrease stigma in young adults with sickle cell disease. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2014;36(5):599–619. doi: 10.1177/0193945913512724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenerette CM, Murdaugh C. Testing the Theory of Self-care Management for sickle cell disease. Research in Nursing Health. 2008;31(4):355–369. doi: 10.1002/nur.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass NE, Hull SC, Natowicz MR, Faden RR, Plantinga L, Gostin LO, Slutsman J. Medical privacy and the disclosure of personal medical information: The beliefs and experiences of those with genetic and other clinical conditions. American Journal of Medical Genetics A. 2004;128a(3):261–270. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauf TL, Coates TD, Huazhi L, Mody-Patel N, Hartzema AG. The cost of health care for children and adults with sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology. 2009;84(6):323–327. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labore N, Mawn B, Dixon J, Andemariam B. Exploring Transition to Self-Management Within the Culture of Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2017;28(1):70–78. doi: 10.1177/1043659615609404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrousse W. Lived experience of young Haitian-American women with sickle cell disease. 68. ProQuest Information & Learning; US: 2007. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2007-99220-004&site=ehost-live&scope=siteAvailablefromEBSCOhostpsyhdatabase. [Google Scholar]

- Lazio MP, Costello HH, Courtney DM, Martinovich Z, Myers R, Zosel A, Tanabe P. A comparison of analgesic management for emergency department patients with sickle cell disease and renal colic. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2010;26(3):199–205. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181bed10c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, … Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. British Medical Journal. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Springer; 2013. Labeling and stigma; pp. 525–541. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur VA, Kiley KB, Haywood C, Jr, Bediako SM, Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, … Campbell CM. Multiple Levels of Suffering: Discrimination in Health-Care Settings is Associated With Enhanced Laboratory Pain Sensitivity in Sickle Cell Disease. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2016;32(12):1076–1085. doi: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthie N, Hamilton J, Wells D, Jenerette C. Perceptions of young adults with sickle cell disease concerning their disease experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2015;72(6):1441–1451. doi: 10.1111/jan.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthie N, Jenerette C, McMillan S. Role of self-care in sickle cell disease. Pain Management Nursing. 2015;16(3):257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell K, Streetly A, Bevan D. Experiences of hospital care and treatment-seeking behavior for pain from sickle cell disease: Qualitative study. Western Journal of Medicine. 1999;171(5–6):306–313. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1308742/pdf/westjmed00315-0020.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulchan SS, Valenzuela JM, Crosby LE, Sang CDP. Applicability of the SMART model of transition readiness for sickle-cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2016;41(5):543–554. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SC, Hackman HW. Race matters: Perceptions of race and racism in a sickle cell center. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2013;60(3):451–454. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ola BA, Yates SJ, Dyson SM. Living with sickle cell disease and depression in Lagos, Nigeria: A mixed methods study. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;161:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Dovidio JF, West TV, Gaertner SL, Albrecht TL, Dailey RK, Markova T. Aversive Racism andMedical Interactions with Black Patients: A Field Study. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46(2):436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed P. Chronic pain stigma: Development of the Chronic Pain Stigma Scale. 2005 Available from http://worldcat.org/z-wcorg/database.

- Royal CD, Jonassaint CR, Jonassaint JC, De Castro LM. Living with sickle cell disease: Traversing ‘race’ and identity. Ethnicity & Health. 2011;16(4–5):389–404. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.563283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar P, Cho MK, Wolpe PR, Schairer C. What is in a cause? Exploring the relationship between genetic cause and felt stigma. Genet Med. 2006;8(1):33–42. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000195894.67756.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scambler G. Health-related stigma. SociolHealth Illness. 2009;31(3):441–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvey NA, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. The stress of stigma: Exploring the effect of weight stigma on cortisol reactivity. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76(2):156–162. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Oyeku SO, Homer C, Zuckerman B. Sickle cell disease:Aquestion of equity and quality. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1763–1770. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton MV, Jonassaint CR, Bartholomew FB, Edwards C, Richman L, DeCastro L, Williams R. The association of optimism and perceived discrimination with health care utilization in adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of National Medical Association. 2010;102(11):1056–1063. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30733-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strouse J, Lobner K, Lanzkron SMHS, Haywood C. NIH and National Foundation Expenditures For Sickle Cell Disease and Cystic Fibrosis Are Associated With Pubmed Publications and FDA Approvals. Blood. 2013;122(21):1739–1739. [Google Scholar]

- Tak-Ying Shiu A, Kwan JJYM, Wong RYM. Social stigma as a barrier to diabetes self-management: Implications for multi-level interventions. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2003;12(1):149–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield EO, Popp JM, Dale LP, Santanelli JP, Pantaleao A, Zempsky WT. Perceived Racial Bias and Health-Related Stigma Among Youth with Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2017;38(2):129–134. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0000000000000381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: Rethinking concepts and interventions 1. Psychology Health & Medicine. 2006;11(3):277–287. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Winker G, Degele N. Intersectionality as multi-level analysis: Dealing with social inequality. European Journal of Women’s Studies. 2011;18(1):51–66. doi: 10.1177/1350506810386084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, Ballas SK, Hassell KL, James AH, … John-Sowah J. Management of sickle cell disease: Summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA. 2014;312(10):1033–1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]