Abstract

Hispanics are the largest racial/ethnic minority group in the U.S., and they experience a substantial burden of kidney disease. Although the prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is similar or slightly lower in Hispanics than non-Hispanics whites, the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence rate of end-stage renal disease is almost 50% higher in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites. This has been attributed in part to faster CKD progression among Hispanics. Furthermore, Hispanic ethnicity has been associated with greater prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors including obesity and diabetes, as well as CKD-related complications. Despite their less favorable socioeconomic status which often leads to limited access to quality health care, and their high comorbidity burden, the risk of mortality among Hispanics appears to be lower than in non-Hispanic whites. This survival paradox has been attributed to a complex interplay between sociocultural and psychosocial factors, as well as other factors. Future research should focus on evaluating the long-term impact of these factors on patient-centered and clinical outcomes. National policies are needed to improve access to and quality of health care among Hispanics with CKD.

Keywords: Hispanics, chronic kidney disease (CKD), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), Latinos, CKD progression, health disparities, undocumented immigrants, proteinuria, diabetic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, ethnic differences, nonmodifiable risk factor, acculturation, minorities, socioeconomic status

Introduction

The term “Hispanic” or “Latino” describes a group of individuals sharing a common cultural heritage and frequently a common language, but it does not necessarily denote to race or a common ancestry.1 Even though Hispanics are considered to be a single ethnic group who can self-identify as any race as defined by the U.S. Census, they represent a heterogeneous mixture of Native American, European, and African ancestries.2 It is estimated that 57.5 million Hispanics currently reside in the U.S., making Hispanics the largest minority in the country, and this number is projected to double in the next 20 years.3 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major public health problem that affects 8-16% of the population worldwide,4 including 1 in 7 adults in the U.S.5 In this review we will discuss the epidemiology of CKD and related comorbidities in U.S. Hispanics, address health disparities that affect this segment of the population, and highlight potential areas for future research.

Epidemiology of CKD in U.S. Hispanics

Incidence

Over 17,000 U.S. Hispanics entered the Medicare end-stage renal disease (ESRD) program in 2014. An increased incidence of ESRD in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics was first reported in the 1980’s in Texas and subsequently confirmed by studies at the national level.6,7 Based on the U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) 2016 data report, the adjusted ESRD incidence rates among Hispanics have been stable or somewhat declining since 2001. However, even though the absolute difference in incident ESRD rates between Hispanics and non-Hispanics has declined over the years, the age-, sex-, and race-adjusted rate remains nearly 35% higher among Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics (456 vs. 337 per million population).8

Less is known about incidence rates of earlier CKD stages. Among participants in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), compared with whites, Hispanics had higher rates of incident CKD (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <60 ml/min/1.73m2 and a decline in eGFR ≥ 1 ml/min/1.73m2 per year): 0.30 vs. 0.09 per year among participants with baseline eGFR >90 ml/min/1.73m2, and 2.32 vs. 1.85 per year among those with baseline eGFR 60-90 ml/min/1.73m2. However, these differences were not statistically significant in multivariable models adjusting for sociodemographic factors (age, gender, income, education) and baseline eGFR. Moreover, although Mexican/Central American and South American Hispanics had similar rates of eGFR decline compared to whites, the authors found faster eGFR decline among Dominicans and Puerto Ricans compared with whites (0.54 and 0.47 ml/min/1.73m2 per year faster, respectively, p<0.05 for each); these differences were statistically significant even after adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical factors.9 In another study of 10,420 patients with hypertension in an inner-city health care delivery system, the risk of incident CKD (defined as eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2 for at least three months) and the rate of eGFR decline over time were similar in Hispanics compared with whites.10 Of note, this retrospective study did not evaluate Hispanics by country of origin, which might explain the apparent discordant findings.

Prevalence

Until a few years ago, information regarding the prevalence of CKD in U.S. Hispanics had been limited to analyses of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which by design includes predominantly Mexican Americans, with minimal representation of the other major U.S. Hispanic background groups.11 Based on these data, compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics were found to have lower prevalence of decreased eGFR11,12 and higher prevalence of albuminuria, even after accounting for the presence of diabetes.13-15 More recently, the prevalence of CKD was estimated in the population-based Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) which includes over 16,000 U.S. Hispanic adults with representation of the major Hispanic background groups.16 Among women, the prevalence of CKD, defined as eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or albuminuria based on sex-specific cut points, was 13.0%, and it was lowest in South Americans (7.4%) and highest in Puerto Ricans (16.6%). In men, the prevalence of CKD was 15.3%, and it was lowest in South Americans (11.2%) and highest in those who identified their Hispanic background as “other” (16.0%). However, the overall prevalence of CKD (14%) was similar to that in non-Hispanic whites in NHANES 2007-2010.17 These findings are in contrast to the higher prevalence of ESRD in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanics. According to USRDS, there were more than 85,000 Hispanics in the U.S. receiving dialysis treatment in 2014, which correspond to a prevalent rate nearly 40% higher in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics (2917 vs. 1847 per million population).8 The higher rate of ESRD despite similar prevalence of CKD in Hispanics vs. non-Hispanics suggests that Hispanics may be at increased risk for CKD progression, or alternatively that the mortality rate prior to the onset of ESRD is lower in Hispanics than in non-Hispanic whites.18 As discussed below, findings from the Hispanic Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (Hispanic CRIC) Study suggest the former.

CKD Progression in Hispanics

Several studies have evaluated the relationship between race/ethnicity and CKD progression,18-23 with some but not all reporting a higher risk of ESRD in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic Whites (Table 1). In a study of nearly 40,000 adults with stage 3 or 4 CKD enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, relative to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanic ethnicity was independently associated with higher risk of progression to ESRD (dialysis or kidney transplantation) during the 4-year mean follow-up period (adjusted HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.17-1.52).20 Similarly, compared with non-Hispanic whites, participants in the Hispanic CRIC Study experienced higher rates of progression to ESRD during a mean follow-up of 5 years (2.6 vs. 1.4 per 100 person-years).23 In multivariable analyses, the risk of CKD progression was 81% higher in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.34-2.45) after adjustment for important sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. However, this excess risk was attenuated and no longer statistically significant after accounting for differences in urine protein excretion (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.96-1.81) regardless of diabetes status; of note, the median 24 hour urine protein excretion at study entry was 0.71 g in Hispanics and 0.12 g in non-Hispanics.23 Importantly, compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics in this study were less likely to achieve recommended goals for CKD management including blood pressure control, secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use.24,25 These disparities in CKD care may have contributed to their higher protein excretion and disease progression among Hispanics. Moreover, at study entry Hispanic CRIC participants were found to have more unfavorable metabolic biomarkers, and a greater burden of left ventricular hypertrophy.24,25

Table 1.

Studies evaluating incident ESRD in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites

| Study | Participants | Setting | DM Prevalence | F/U, y | Outcome | Confounders | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

|

Individuals without established CKD

| |||||||

| Young et al (2003)19 | 429,918; 6.2% | U.S. Veterans | 100% | 1 | ESRD attributed to diabetes | Age, sex, HTN, CVD, nonservice connection, no. of visits, region | 1.4 (1.3–1.4)a |

| Hispanic; 90% | |||||||

| Non-CKD | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Derose et al (2013)18 | 994,055; 33% | KP Southern California | NA | 5 | Predicted eGFR <15 | Age, sex, entry eGFR | 0.92 (0.89-0.94)a |

| Hispanic; entry | |||||||

| eGFR > 60 | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Individuals with established CKD

| |||||||

| Peralta, 200620 | 39,550; 31% | KP Northern California | 15% | 4 | ESRD | Age, sex, income, education, language, HTN, CVD, DM, insulin, baseline eGFR, proteinuria, medications | 1.33 (1.17-1.52) |

| Hispanic; CKD3-4 | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Derose, 201318 | 125,761; 16% | KP Southern California | NA | 5 | Predicted eGFR <15 | Age, sex, entry eGFR | 1.49 (1.42-1.56)a |

| Hispanic; CKD3-4 | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Lewis, 201522 | 4,038; 13% | TREAT Study | 100% | 2 | ESRD | Race, age, sex, BMI, insulin, eGFR, SUN, albumin, Hb, ferritin, CRP, proteinuria, AKI, duration of DM, systolic & diastolic BP, HbA1c, CVD | 1.01 (0.79-1.29) |

| Hispanic; CKD3-4 | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Fischer, 201623 | 3,785; 13% | CRIC Study | 47% | 5 | ESRD | Age, sex, baseline eGFR, DM, education, health insurance, nephology care, smoking, systolic BP, ACEi/ARB use, BMI, HbA1c, proteinuria | 1.32 (0.96-1.81) |

| Hispanic; CKD3-4 | |||||||

Odds ratio instead of hazard ratio

Abbreviations: ACEi/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; AKI, acute kidney injury; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; CRIC, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (in mL/min/1.73 m2), ESRD, end-stage renal disease; Hb, hemoglobin; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HTN, hypertension; HR, hazard ratio; KP, Kaiser Permanente; NA, not available; TREAT, Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events with Aranesp Therapy.

Risk Factors for CKD and Comorbid Conditions in Hispanics

Diabetic Kidney Disease

Over their lifetime, more than 50% of U.S. Hispanics are expected to develop type 2 diabetes.26 Even though incidence rates for ESRD attributed to diabetes have stabilized or slightly declined over the past 10 years, diabetes remains the main cause of ESRD among U.S. Hispanics,8 Furthermore, the risk of ESRD attributed to diabetes has been found to be greater in Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic whites.8,19 Racial/ethnic differences in protein excretion among persons with diabetes have also been observed.27,23 Environmental and genetic factors have been proposed as potential mechanisms to explain these differences.28

Genetic Factors

The Hispanic population within the U.S. is genetically diverse, with various proportions of Native American, African, and European genetic ancestry, depending on historical interactions with migrants from Europe and Africa, and Native American populations.2 Therefore, it is not surprising that the prevalence of CKD and its risk factors (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, obesity) among Hispanics vary by country of origin.16,29-33 The proportion of African genetic ancestry, which is higher among the Caribbean (Puerto Rican, Dominican or Cuban) than in the Mainland (Mexican, Central or South American) group, has been associated with risk of CKD.34 A recent study from HCHS/SOL showed that presence of two copies of APOL1 risk alleles, found in chromosomal regions of African ancestry, is associated with prevalent CKD among Hispanics.35 Of note, in this study, Caribbean Hispanics had ten-fold higher frequency of two APOL1 risk alleles versus zero/one copy (1% vs. 0.1%) compared with Mainland Hispanics. In another study, two APOL1 risk alleles predicted lower age of dialysis initiation among Hispanics with non-diabetic ESRD.36 Furthermore, studies have found an association between increased urine albumin excretion and Native American ancestry in Hispanics,1,30 which have been attributed to specific genetic variants found among Pima Indians.37 Future studies should examine whether the genetic variants discussed are associated with incident and/or progression of CKD in the Hispanics.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular event rates are two- to five-times higher in patients with CKD compared with those without CKD.38-40 Whether the excess cardiovascular risk conferred by CKD is of the same magnitude among Hispanics as in non-Hispanics remains largely understudied. In a pooled analysis of three community-based cohorts, the excess risk of heart failure associated with CKD was large among Hispanics with CKD vs. without CKD (adjusted risk difference per 1000 person-years, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.5-5.5) compared with whites (adjusted risk difference per 1000 person-years, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.6-2.6). Similar findings were observed for coronary heart disease in Hispanics with CKD vs. without CKD (adjusted risk difference per 1000 person-years, 12.9; 95% CI, 4.5-21.4), compared with whites with CKD vs. without CKD (adjusted risk difference per 1000 person-years, 2.0; 95% CI, 0.8-3.2).41 Of note, the number of Hispanics with CKD in these cohorts was only 109.

Studies evaluating the risk of cardiovascular disease in Hispanics vs. non-Hispanics with CKD have shown heterogeneous results. In cross-sectional analyses of data from the CRIC Study, Hispanics had higher odds of left ventricular hypertrophy compared with non-Hispanic whites, even after adjusting for demographic and clinical variables including blood pressure. However, the risk of coronary artery calcification was similar between the two groups.25 In longitudinal analysis of the same cohort, Hispanics experienced almost a two-fold higher crude rate of heart failure events than non-Hispanic whites but this difference attenuated after multivariable adjustment. Furthermore, Hispanics were not at increased risk atherosclerotic events compared to non-Hispanics whites.42 In contrast, two prior studies had shown that compared with non-Hispanic whites with CKD, Hispanics with CKD had lower risk for atherosclerotic events.20,22

There continues to be limited data regarding cardiovascular disease in Hispanics with ESRD. In an analysis of over 270,000 incident ESRD patients, the risk of incident myocardial infarction among individuals with prevalent cardiovascular disease was observed to be significantly lower in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.68-0.77).43 In contrast, in another study of patients with incident ESRD attributed to lupus nephritis, Hispanics were found to have similar risk of atherosclerotic and heart failure events compared with non-Hispanic whites.44 Additional studies on cardiovascular outcomes in Hispanics with ESRD are needed.

Mortality in Hispanics with CKD and ESRD

It is well established that U.S. Hispanics with ESRD receiving dialysis have lower mortality risk than non-Hispanic whites (Table 2),45-49,44 with reported 2014 mortality rates per 1,000 person-years of 206 in non-Hispanic whites vs. 127 in Hispanics.8 This is despite adverse socioeconomic characteristics and higher comorbidity burden among Hispanics, a phenomenon that has been referred to as the “Hispanic paradox”, given opposite observations in the U.S. general population. Although this racial/ethnic disparity is poorly understood, it has been attributed to incomplete and/or suboptimal ascertainment of comorbidity burden among Hispanics and non-Hispanics in the available studies (i.e. measurement error, ascertainment bias), salmon bias (i.e., return migration of Hispanics to country of origin to die), healthy migrant effect (i.e., younger healthy Hispanic immigrants), differences in inflammation and nutrition, and psychosocial/sociocultural factors.50,51

Table 2.

Studies evaluating all-cause mortality risk in Hispanics vs. non-Hispanics with CKD

| Study | Participants | Setting | DM Prevalence | F/U, y | Confounders | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ESRD | ||||||

| Peralta et al (2006)20 | 39,550; 31% Hispanic; CKD3-4 | KP Northern California | 15% | 4 | Age, sex, income, education, language, HTN, CVD, DM, insulin, baseline eGFR, proteinuria, medications | 0.71 (0.65- 0.77) |

| Mehrotra et al (2008)52 | 2892; % Hispanic NA; CKD3-4 | NHANES III | 24% | 9 | Age, sex, HTN, cholesterol, BMI, DM, smoking, family history of premature CVD, stage of CKD | 1.26 (0.84- 1.90)* |

| Derose, 201318 | 1,119,816**; 31% Hispanic | KP Southern California | __*** | 5 | Age, sex, entry eGFR | 0.67 (0.63- 0.72)** |

| Lewis, 201522 | 4,038; 13% Hispanic; CKD3-4 | TREAT Study | 100% | 2 | Race, age, sex, BMI, insulin, eGFR, SUN, albumin, Hb, ferritin, CRP, proteinuria, AKI, DM, BP, HbA1c, CVD, medications, smoking, blood transfusion, heart rate, reticulocytes, WBC count, gout, GI bleeding, lung disease, treatment randomization | 0.86 (0.66- 1.10) |

| Fischer, 201623 | 3,785; 13% Hispanic; CKD3-4 | CRIC Study | 47% | 5 | Age, sex, baseline eGFR, DM, education, health insurance, nephology care, smoking, systolic BP, ACEi/ARB use, BMI, HbA1c, proteinuria | 0.89 (0.59- 1.35) |

| ESRD | ||||||

| Frankenfield, 200345 | 8,336; 12% Hispanic | ESRD CPM Project | 40% | 1 | Age, sex, ethnicity, DM, years on dialysis, BMI, amputations, mean Kt/V, catheter access, Hb, albumin, ESRD Network | 0.76 (0.60- 0.96) |

| Murthy, 200546 | 100,618; 10% Hispanic | USRDS 1995- 1997 | 42% | 2 | Age, sex, race, HTN, CVD, smoking, COPD, AIDS, cancer, alcohol dependence, BMI, serum albumin, Hct, eGFR, functional status, pre-ESRD EPO use | DM: 0.70 (0.66- 0.74); no DM: 0.83 (0.77- 0.91) |

| Yan, 201349 | 1,282,201; 12- 20% Hispanic | USRDS 1995- 2009 | 15-67% | 2 | Age, sex, insurance, BMI, lifestyle, immobility, cause of ESRD, dialysis modality, pre-ESRD use of ESAs, comorbid conditions | 0.70 (0.69– 0.70) |

| Arce, 201347 | 615,618; 17% Hispanic | USRDS 1995- 2007 | 50% | --*** | Age, sex, year, comorbid conditions, dialysis modality, insurance, BMI, eGFR | 0.84 (0.83- 0.86)† |

| Rhee, 201448 | 130,909; 16% Hispanic | Private U.S. dialysis provider | 43% | 2 | Age, sex, insurance, BMI, dialysis modality, DM, smoking, alcohol/drug dependence, HTN, CVD, COPD, cancer, functional status, eGFR, Kt/v, serum phosphate, albumin, TIBC, calcium, bicarbonate, creatinine, ferritin, Hb, WBC count, lymphocyte %, PCR | 0.77 (0.73- 0.81)‡ |

| Gomez- Puerta, 201544 | 12,533; 16% Hispanic; ESRD due to LN | USRDS 1995– 2008 | 9% | 3 | Age, sex, year, insurance, BMI, eGFR, albumin, employment, area-level SES, U.S. region, dialysis modality, smoking, HTN, DM, CVD, COPD, cancer | 0.79 (0.71– 0.88) |

HR for age strata <65 years

HR of death among those with projected kidney failure during CKD stages 3-4.

not applicable

HR for age strata 60-79 years

HR for age strata 60-70 years

Abbreviations: ACEi/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPM, Clinical Performance Measures; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate, EPO, erythropoietin; ESA, erythropoietin-stimulating agent; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; GI, gastrointestinal; Hb, hemoglobin; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; HTN, hypertension; HR, hazard ratio; KP, Kaiser Permanente; LN: lupus nephritis; NA, not available; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; PCR, protein catabolic rate; SES, socio-economic status; TIBC, total iron binding capacity; USRDS, U.S. Renal Data System; WBC, white blood cell.

Among Hispanics with non-dialysis-dependent CKD, mortality risk have also been found to be lower18,20 or similar22,23,52 to non-Hispanic whites (Table 2). Findings from the Hispanic CRIC Study suggest that proteinuria significantly modifies the relationship between race/ethnicity and mortality. Although at lesser levels of proteinuria Hispanics had a similar mortality risk compared with non-Hispanic whites, their mortality risk was significantly lower at greater levels of proteinuria.23 There are limiting data regarding differences in mortality between Hispanic background groups. One study evaluating individuals randomly selected for the ESRD Clinical Performance Measures Project reported a significantly lower 2-year mortality risk among Mexican-Americans compared with non-Hispanics (adjusted HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.73-0.85). Mortality risk was similar in Puerto Ricans and Cuban-Americans relative to non-Hispanics.53

Disparities in Access to Care

Overview

More than 25% of U.S. Hispanics report not having a regular health care provider,54 which is more than double the proportion for non-Hispanics whites. This disparity is likely related to socioeconomic factors including education, language, and lack of health insurance. Not surprisingly, Hispanics are less likely to receive pre-ESRD care than non-Hispanics. Hispanic participants in the CRIC Study were less likely to report prior contact with a nephrologist at study entry compared with non-Hispanic whites (OR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.47).55 Moreover, the proportion of CKD Hispanic patients receiving care from a nephrologist at least 12 months before the start of renal replacement therapy was lower among Hispanics, at 27.0%, compared with 36.7% in whites.8 This disparity in nephrology care partially explained the lower use of arteriovenous access for first outpatient hemodialysis compared with non-Hispanics.56

Access to kidney transplant

The proportion of U.S. dialysis patients receiving a kidney transplant within three years of ESRD diagnosis is lower in Hispanics (11%) compared with non-Hispanics (14%).8 According to the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients 2015 Annual Report, Hispanics constituted 19.6% and whites 36.5% of adults on the kidney transplant waiting list. However, Hispanics received only 17.2% of all kidney transplants in that year, compared with 46.2% in whites. The difference in percent of living kidney transplantation between Hispanics and whites was particularly striking (15.0% vs. 65.7%).57 Barriers to living kidney donation identified among Hispanics include knowledge deficit about the procedure and fear of financial and health-related long-term consequences of kidney donation.58

A study of 388 Hispanics undergoing dialysis in December 1994 in Arizona and New Mexico found that despite similar kidney transplant referral rates, Hispanics were less likely to be placed on a waiting list compared with non-Hispanic whites.59 In contrast, another study of 417,801 patients who initiated dialysis in the U.S. between 1995 and 2007, found no differences in the time from dialysis initiation to placement on the transplant waitlist between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites.60 However, once waitlisted, Hispanics were less likely to undergo deceased donor kidney transplantation, even after taking into account the survival advantage among Hispanics (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.77-0.81). Adjustment for blood type and organ procurement organization explained this disparity, suggesting that the Hispanic population tends to live in high-population-density organ procurement organizations with limited availability of organs.60 As discussed in the next section of the review, limited access to kidney transplantation among Hispanics is more pronounced among those who are considered unauthorized immigrants. After transplantation, graft and patient survival among recipients of kidney transplants appears to be similar or higher among Hispanics compared with whites.61-63

Social Determinants of Health

Overview

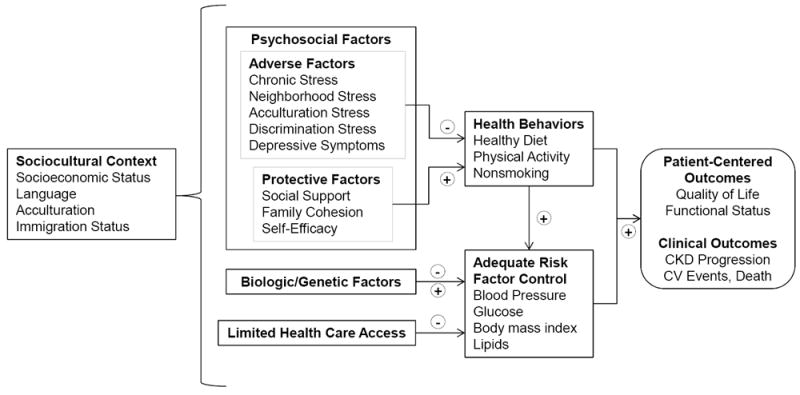

Sociocultural and psychosocial factors may play an important role in CKD progression in Hispanics and account for racial/ethnic disparities in CKD-related health outcomes. The conceptual model presented in Figure 1 is adapted from the Lifespan Biopsychosocial Model.64,65 This model suggests that sociocultural factors including socioeconomic status and acculturation may influence psychosocial factors, some of which are adverse (e,g,, chronic stress, depression) and others protective (e.g., social support, family cohesion). These sociocultural and psychosocial factors may in turn have direct and indirect effects on health outcomes. The model also takes into account other potentially important factors such as access to health care, health behaviors, risk factor control, and biological/genetic factors. Several studies have found that Hispanics born in the U.S. have a greater prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors than first generation immigrants,33,66 suggesting that acculturation (i.e., adoption of values and lifestyle associated with the U.S. culture) may be associated with adverse health outcomes.67 On the other hand, Hispanics who are undocumented immigrants face a unique set of personal and familiar stressors which might affect their health. In contrast, it has also been postulated that factors such as family cohesion and social support may be partially responsible for the lower mortality rates observed in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites.50,68 Below we will discuss two of the most relevant factors pertaining to Hispanics in the U.S., acculturation and immigration status.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for Health Outcomes in Hispanics with CKD

Acculturation

Acculturation refers to cultural modification that occurs as one takes on attitudes, customs, traditions, and behaviors of another culture.69 While acculturation is difficult to ascertain, it may provide insight into health disparities among Hispanics. There is conflicting data on the role of acculturation on chronic diseases in this ethnic group. For example, less acculturation has been associated with lower prevalence of hypertension and diabetes, but also with poorly controlled blood pressure and higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors.70-72 Studies evaluating the role of acculturation in kidney function among Hispanics are scarce. Among Hispanics enrolled in MESA, greater acculturation (speaking mixed Spanish/English at home compared with Spanish only) was associated with lower eGFR and higher albumin-creatinine ratio. Furthermore, U.S.-born Hispanics had lower eGFR compared with those who were foreign born.73 Additional studies examining the association between acculturation and CKD among Hispanics are needed.

Impact of ESRD on undocumented persons

Of the nearly 58 million Hispanics currently living in the U.S., approximately 11 million are considered “unauthorized immigrants”.74 Although the true prevalence of ESRD in this population is unknown, it has been estimated that there are over 6,000 undocumented immigrants with ESRD in the U.S.,75 and the majority of them are of Hispanic origin.76 Due to their lack of legal status, these individuals are not eligible for federal insurance programs, and less than a third of them are able to acquire private health insurance through their employer.77 Unfortunately, a national policy addressing the provision of renal replacement therapy to this vulnerable population does not exist.78 Therefore, the care for undocumented patients with ESRD varies from state to state and is often suboptimal. Some states such as California and Illinois have been able to secure funding to provide standard maintenance hemodialysis. However, in other states like Georgia and Texas, dialysis is only provided on an emergency-only basis.75 Novel strategies such as purchase of health care plans off the government-sponsored health insurance marketplace exchange have benefited some undocumented patients with ESRD.77, 77a However, the sustainability of these programs is uncertain and more definitive policies at the national level are urgently needed.

As might be expected, the outcomes of patients receiving dialysis “as needed” are worse compared with those receiving standard of care. In a recent retrospective cohort study of 211 undocumented patients with ESRD, those receiving emergency-only hemodialysis had more than 14-fold higher mortality and spent more days in the hospital compared with those who received thrice weekly treatment.79 Furthermore, based on a qualitative study of 20 undocumented patients with ESRD and no access to scheduled hemodialysis in Colorado, emergency-only hemodialysis results in debilitating physical symptoms and marked psychosocial distress among patients and their families.80 This clearly represents an ethical challenge for nephrologists who are confronted with patients in desperate need but a health care system without the appropriate resource allocation.76

Access to kidney transplantation is even more limited for these patients because undocumented immigrants are not eligible for federal subsidies to pay for the procedure, and most lack the economic resources to pay out of pocket. Even though kidney transplantation results in better quality of life and longer patient survival, and is a more cost-effective treatment for ESRD than dialysis, the majority of undocumented immigrants are deprived of this opportunity because of non-medical reasons.78,81 One of the arguments to exclude undocumented immigrants from access to kidney transplantation is that the risk of graft failure would be higher compared with legal persons due to risk of deportation and lack of resources to pay for post-transplant care, including immunosuppression medications. This argument has been recently disputed by clinical research.81 In a recently published retrospective cohort study, Shen et al. compared all-cause transplant loss among all-adult Medicaid patients in the USRDS by citizenship status. Out of 10,495 patients who received a kidney transplant between 1990 and 2011, 3% were nonresident aliens (assumed to be undocumented immigrants) who were younger, healthier, and more likely to have a living donor. The study showed that the adjusted risk of kidney allograft loss was significantly lower among nonresident aliens compared with Medicaid U.S. citizens (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.94).81 Even though additional, prospective studies should be conducted to better understand the complexities of this issue, these findings are encouraging and should be taken into consideration when drafting health policy.

Research priorities and Conclusions

Based on the data summarized in this review, the observed higher risk of ESRD among Hispanics appears to be explained largely by potentially modifiable factors, in particular urine protein excretion. Therefore, future research should focus on the implementation of cost-effective strategies for early detection and management of albuminuria among Hispanics. In addition, longitudinal studies evaluating the impact of sociocultural and psychosocial factors, including acculturation, on clinical and patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life and disease progression among Hispanics with CKD are needed.

In summary, Hispanics are a culturally, socioeconomically, and genetically heterogeneous segment of the U.S. population with a high burden of CKD and its risk factors, but paradoxically have higher overall survival rates compared with non-Hispanic whites. Most of the studies currently available suggest that the excess risk for kidney function decline among Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics is in part attributable to socioeconomic and clinical factors. These findings might indicate that disparities in CKD progression between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites are potentially modifiable. Given the high prevalence of diabetes and obesity among U.S. Hispanics, as well as the limited access to adequate medical care, public health initiatives for primary and secondary prevention of CKD among Hispanics should have a positive impact in this population.

Acknowledgments

Support: Dr Ricardo is funded by the NIDDK K23DK094829 Award. Dr. Lash is funded by the NIDDK K24DK092290 and R01-DK072231-91 Awards.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.González Burchard E, Borrell LN, Choudhry S, et al. Latino populations: a unique opportunity for the study of race, genetics, and social environment in epidemiological research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2161–2168. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, Reich D, Mountain JL. The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(1):37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [October 4, 2017];US Census Bureau: Hispanic Heritage Month 2017. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/hispanic-heritage.html.

- 4.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet Lond Engl. 2013;382(9888):260–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States ∣ NIDDK. [August 9, 2017];National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/kidney-disease.

- 6.Pugh JA, Stern MP, Haffner SM, Eifler CW, Zapata M. Excess incidence of treatment of end-stage renal disease in Mexican Americans. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127(1):135–144. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiapella AP, Feldman HI. Renal failure among male Hispanics in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(7):1001–1004. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US Renal Data System 2016 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69((3)(suppl 1)):S1–S688. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peralta CA, Katz R, DeBoer I, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in kidney function decline among persons without chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2011;22(7):1327–1334. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010090960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanratty R, Chonchol M, Miriam Dickinson L, et al. Incident chronic kidney disease and the rate of kidney function decline in individuals with hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc. 2010;25(3):801–807. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coresh J, Byrd-Holt D, Astor BC, et al. Chronic kidney disease awareness, prevalence, and trends among U.S. adults, 1999 to 2000. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2005;16(1):180–188. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CA, Francis ME, Eberhardt MS, et al. Microalbuminuria in the US population: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2002;39(3):445–459. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.31388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryson CL, Ross HJ, Boyko EJ, Young BA. Racial and ethnic variations in albuminuria in the US Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) population: associations with diabetes and level of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2006;48(5):720–726. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolly SE, Burrows NR, Chen S-C, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in albuminuria in individuals with estimated GFR greater than 60 mL/min/1.73 m(2): results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2010;55(3 Suppl 2):S15–22. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ricardo AC, Flessner MF, Eckfeldt JH, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of CKD in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2015;10(10):1757–1766. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02020215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy D, McCulloch CE, Lin F, et al. Trends in Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(7):473–481. doi: 10.7326/M16-0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derose SF, Rutkowski MP, Crooks PW, et al. Racial differences in estimated GFR decline, ESRD, and mortality in an integrated health system. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2013;62(2):236–244. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young BA, Maynard C, Boyko EJ. Racial differences in diabetic nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in a national population of veterans. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2392–2399. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Fan D, et al. Risks for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular events, and death in Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white adults with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2006;17(10):2892–2899. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Zeeuw D, Ramjit D, Zhang Z, et al. Renal risk and renoprotection among ethnic groups with type 2 diabetic nephropathy: a post hoc analysis of RENAAL. Kidney Int. 2006;69(9):1675–1682. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis EF, Claggett B, Parfrey PS, et al. Race and ethnicity influences on cardiovascular and renal events in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am Heart J. 2015;170(2):322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer MJ, Hsu JY, Lora CM, et al. CKD Progression and Mortality among Hispanics and Non-Hispanics. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2016;27(11):3488–3497. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer MJ, Go AS, Lora CM, et al. CKD in Hispanics: Baseline characteristics from the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) and Hispanic-CRIC Studies. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2011;58(2):214–227. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricardo AC, Lash JP, Fischer MJ, et al. Cardiovascular disease among hispanics and non-hispanics in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2011;6(9):2121–2131. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11341210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC. Hispanic Diabetes Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [October 5, 2017]. https://www.cdc.gov/features/hispanichealth/. Published September 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhalla V, Zhao B, Azar KMJ, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of proteinuric and nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1215–1221. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA. 2002;287(19):2519–2527. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneiderman N, Llabre M, Cowie CC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics/Latinos from diverse backgrounds: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2233–2239. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peralta CA, Li Y, Wassel C, et al. Differences in albuminuria between Hispanics and whites: an evaluation by genetic ancestry and country of origin: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3(3):240–247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.914499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pabon-Nau LP, Cohen A, Meigs JB, Grant RW. Hypertension and diabetes prevalence among U.S. Hispanics by country of origin: the National Health Interview Survey 2000-2005. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):847–852. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1335-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorlie PD, Allison MA, Avilés-Santa ML, et al. Prevalence of hypertension, awareness, treatment, and control in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, et al. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308(17):1775–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Udler MS, Nadkarni GN, Belbin G, et al. Effect of Genetic African Ancestry on eGFR and Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2015;26(7):1682–1692. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kramer HJ, Stilp AM, Laurie CC, et al. African Ancestry-Specific Alleles and Kidney Disease Risk in Hispanics/Latinos. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2017;28(3):915–922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tzur S, Rosset S, Skorecki K, Wasser WG. APOL1 allelic variants are associated with lower age of dialysis initiation and thereby increased dialysis vintage in African and Hispanic Americans with non-diabetic end-stage kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc. 2012;27(4):1498–1505. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown LA, Sofer T, Stilp AM, et al. Admixture Mapping Identifies an Amerindian Ancestry Locus Associated with Albuminuria in Hispanics in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2017;28(7):2211–2220. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016091010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu C. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manjunath G, Tighiouart H, Ibrahim H, et al. Level of kidney function as a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular outcomes in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2004;15(5):1307–1315. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000123691.46138.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bansal N, Katz R, Robinson-Cohen C, et al. Absolute Rates of Heart Failure, Coronary Heart Disease, and Stroke in Chronic Kidney Disease: An Analysis of 3 Community-Based Cohort Studies. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(3):314–318. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lash JP, Ricardo AC, Roy J, et al. Race/Ethnicity and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Adults With CKD: Findings From the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) and Hispanic CRIC Studies. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2016;68(4):545–553. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.03.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young BA, Rudser K, Kestenbaum B, Seliger SL, Andress D, Boyko EJ. Racial and ethnic differences in incident myocardial infarction in end-stage renal disease patients: The USRDS. Kidney Int. 2006;69(9):1691–1698. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gómez-Puerta JA, Feldman CH, Alarcón GS, Guan H, Winkelmayer WC, Costenbader KH. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Mortality and Cardiovascular Events Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease Due to Lupus Nephritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67(10):1453–1462. doi: 10.1002/acr.22562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frankenfield DL, Rocco MV, Roman SH, McClellan WM. Survival advantage for adult Hispanic hemodialysis patients? Findings from the end-stage renal disease clinical performance measures project. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2003;14(1):180–186. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000037400.83593.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murthy BVR, Molony DA, Stack AG. Survival Advantage of Hispanic Patients Initiating Dialysis in the United States Is Modified by Race. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(3):782–790. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arce CM, Goldstein BA, Mitani AA, Winkelmayer WC. Trends in Relative Mortality Between Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Whites Initiating Dialysis: A Retrospective Study of the US Renal Data System. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(2):312–321. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhee CM, Lertdumrongluk P, Streja E, et al. Impact of age, race and ethnicity on dialysis patient survival and kidney transplantation disparities. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39(3):183–194. doi: 10.1159/000358497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan G, Norris KC, Yu AJ, et al. The relationship of age, race, and ethnicity with survival in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2013;8(6):953–961. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09180912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(3):496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Norris KC, Agodoa LY. Unraveling the racial disparities associated with kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(3):914–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mehrotra R, Kermah D, Fried L, Adler S, Norris K. Racial Differences in Mortality Among Those with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2008;19(7):1403–1410. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frankenfield DL, Krishnan SM, Ashby VB, Shearon TH, Rocco MV, Saran R. Differences in Mortality Among Mexican-American, Puerto Rican, and Cuban-American Dialysis Patients in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(4):647–657. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hispanics and Health Care in the United States. [October 26, 2017];Pew Research Center. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/08/13/hispanics-and-health-care-in-the-united-states-access-information-and-knowledge/

- 55.Ricardo AC, Roy JA, Tao K, et al. Influence of Nephrologist Care on Management and Outcomes in Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):22–29. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3452-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arce CM, Mitani AA, Goldstein BA, Winkelmayer WC. Hispanic ethnicity and vascular access use in patients initiating hemodialysis in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2012;7(2):289–296. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08370811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2015 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. 2017;17(Suppl 1):21–116. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gordon EJ, Mullee JO, Ramirez DI, et al. Hispanic/Latino concerns about living kidney donation: a focus group study. Prog Transplant Aliso Viejo Calif. 2014;24(2):152–162. doi: 10.7182/pit2014946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sequist TD, Narva AS, Stiles SK, Karp SK, Cass A, Ayanian JZ. Access to renal transplantation among American Indians and Hispanics. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2004;44(2):344–352. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arce CM, Goldstein BA, Mitani AA, Lenihan CR, Winkelmayer WC. Differences in access to kidney transplantation between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites by geographic location in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2013;8(12):2149–2157. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01560213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gjertson DW. Determinants of long-term survival of adult kidney transplants: a 1999 UNOS update. Clin Transpl. 1999:341–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fan P-Y, Ashby VB, Fuller DS, et al. Access and outcomes among minority transplant patients, 1999-2008, with a focus on determinants of kidney graft survival. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. 2010;10(4 Pt 2):1090–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arce CM, Lenihan CR, Montez-Rath ME, Winkelmayer WC. Comparison of longer-term outcomes after kidney transplantation between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites in the United States. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. 2015;15(2):499–507. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Myers HF. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: an integrative review and conceptual model. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gallo LC, Bogart LM, Vranceanu A-M, Matthews KA. Socioeconomic status, resources, psychological experiences, and emotional responses: a test of the reserve capacity model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(2):386–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, et al. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(7):593–625. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lora CM, Gordon EJ, Sharp LK, Fischer MJ, Gerber BS, Lash JP. Progression of CKD in Hispanics: potential roles of health literacy, acculturation, and social support. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2011;58(2):282–290. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinosa de los Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? J Pers. 2009;77(6):1707–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.LaFromboise T, Coleman HLK, Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: evidence and theory. Psychol Bull. 1993;114(3):395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moran A, Diez Roux AV, Jackson SA, et al. Acculturation is associated with hypertension in a multiethnic sample. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(4):354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kandula NR, Diez-Roux AV, Chan C, et al. Association of acculturation levels and prevalence of diabetes in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1621–1628. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eamranond PP, Legedza ATR, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Association between language and risk factor levels among Hispanic adults with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes. Am Heart J. 2009;157(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Day EC, Li Y, Diez-Roux A, et al. Associations of acculturation and kidney dysfunction among Hispanics and Chinese from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc. 2011;26(6):1909–1916. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.NW 1615 L. St, Washington S 800, Inquiries D 20036 U-419-4300 ∣ M-419-4349 ∣ F-419-4372 ∣ M. U.S. unauthorized immigration population estimates. [January 26, 2018];Pew Res Cent Hisp Trends Proj. 2016 Nov; http://www.pewhispanic.org/interactives/unauthorized-immigrants/

- 75.Rodriguez RA. Dialysis for undocumented immigrants in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(1):60–65. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Campbell GA, Sanoff S, Rosner MH. Care of the undocumented immigrant in the United States with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2010;55(1):181–191. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raghavan R. New Opportunities for Funding Dialysis-Dependent Undocumented Individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2017;12(2):370–375. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03680316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77a.Raghavan R. Caring for Undocumented Immigrants With Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(4):488–494. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cervantes L, Grafals M, Rodriguez RA. The United States Needs a National Policy on Dialysis for Undocumented Immigrants With ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):157–159. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cervantes L, Tuot D, Raghavan R, et al. Association of Emergency-Only vs Standard Hemodialysis With Mortality and Health Care Use Among Undocumented Immigrants With End-stage Renal Disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Dec; doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cervantes L, Fischer S, Berlinger N, et al. The Illness Experience of Undocumented Immigrants With End-stage Renal Disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):529–535. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shen JI, Hercz D, Barba LM, et al. Association of Citizenship Status With Kidney Transplantation in Medicaid Patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;712:182–190. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]