Abstract

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the commonest sub-type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. However, lung consolidation is a rare presentation of DLBCL. Moreover, in view of poor general condition, it poses clinical dilemma of when to start chemotherapy and whether chemotherapy should be given at full dose or truncated doses till improvement in general condition. A 48-years-old lady was admitted with complaints of non-productive cough for 2 months duration. She was febrile and hypoxemic requiring oxygen supplementation. She had bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy, and bronchial breath sounds on chest auscultation. Chest X-ray showed non-homogenous opacities involving bilateral lower zones. A diagnosis of DLBCL was confirmed on lymph node biopsy and Immunohistochemistry. She received chemotherapy, following which a gradual, improvement in her breathlessness and cough was noted over ensuing week and she got discharged from the hospital and received rest of her chemotherapy on outpatient basis. In a case of DLBCL with lung consolidation, a high index of suspicion can clinch the diagnosis of secondary lymphomatous involvement. Presence of respiratory failure at presentation doesn’t necessarily warrants truncation of chemotherapy doses.

Keywords: Lymphoma, Pneumonia, Infection, Emergency medicine, Chemotherpy, Imaging

Dear editor,

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the commonest sub-type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), reported in 30–40% of newly diagnosed NHL [1]. Being an aggressive lymphoma, once diagnosed, it demands rapid diagnosis and prompt initiation of therapeutic measures failing which, fatal outcome is expected [2]. However, patient’s general condition (performance score) and co-morbidity can be a hindrance to the prompt initiation of chemo-therapeutic measures. The case being reported here, presented similar challenges to us. The chemotherapy was being delayed and the patient was deteriorating. However, high clinical suspicion and rapid diagnostic measures resulted in prompt initiation of chemotherapy, resulting in satisfactory outcome.

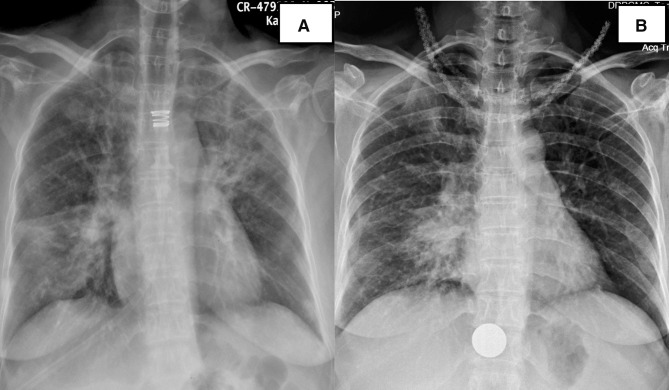

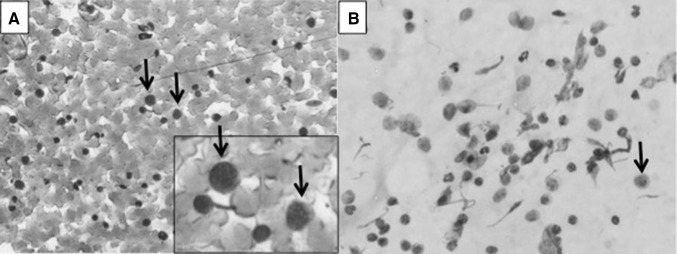

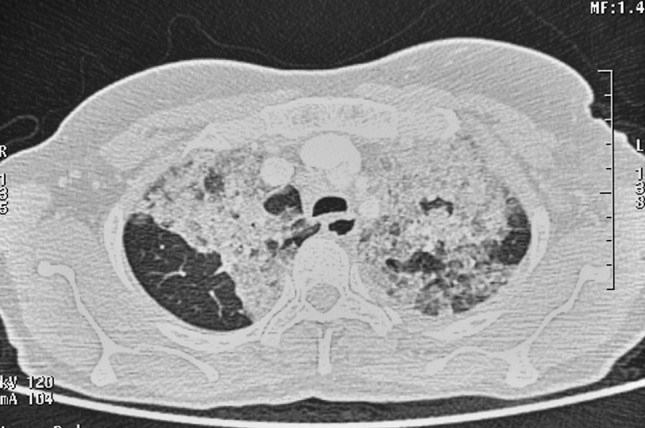

A 48-years-old lady with no known comorbidity was admitted with complaints of non-productive cough for 2 months duration. In addition, she had fever (maximum 101 °F), generalized weakness and breathlessness on exertion (mMRC grade 2) for 1 month. She obtained no relief despite taking oral amoxicillin-clavulinate and cough syrups for 2 weeks. On examination, she had pallor, fever (100.5 °F), tachycardia (96/min), tachypnea (respiratory rate 28/min), bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy (largest 2.5 × 3 cm on right side) and splenomegaly (4 cm palpable below left costal margin). Chest auscultation revealed bronchial breath sounds in bilateral infra-scapular regions and right inframammary region. Chest X-ray showed non-homogenous opacities involving bilateral lower zones (Fig. 1a). A diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia was made and she was started on oxygen supplementation via ventimask (@ 0.35 FiO2); empirical antibiotics inj. piperacillin-tazobactum 4.5 g IV eight hourly and oral azithromycin 500 mg once daily. Contrast enhanced CT scan of chest and abdomen showed multiple enlarged mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes, bilateral lower lobe consolidations and moderate splenomegaly (Fig. 2). Excision biopsy of right axillary lymph node was suggestive of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma, which was confirmed by bright CD20 and MUM1 positivity on Immunohistochemistry. Bone marrow examination didn’t reveal any evidence of infiltration by lymphoma; 2D ECHO was normal. Diagnosed as a case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Ann Arbor stage III BES), she was planned for chemotherapy (R-CHOP: rituximab @375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide @750 mg/m2, vincristine @1.4 mg/m2 and oral prednisolone @60 mg/m2). However, despite 4 days of intravenous antibiotic therapy there was worsening of hypoxemia with increase in oxygen requirement. Her blood cultures were sterile. In view of worsening general condition, possibility of tuberculosis, interstitial lung disease, connective tissue disease and neoplastic disorder were considered. She underwent fibreoptic bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage, which were inconclusive; work up for pulmonary embolism was also inconclusive (normal CT pulmonary angiography). However, CT guided FNAC from the right lower lobe lung lesion had features suggestive of infiltration by DLBCL (Fig. 3a, b) with no evidence of any infectious etiology. Subsequent to this report, she was administered chemotherapy. Gradually, breathlessness and cough completely resolved over 7 days and she was discharged from the hospital. On follow up in outpatient department 2 weeks later, she was afebrile with no cough or breathlessness; repeat chest x-ray showed partial resolution of lung parenchymal infiltrates (Fig. 1b) and pulmonary function tests were normal. At the end of four cycles of chemotherapy an interim assessment by PET-CT has revealed complete remission.

Fig. 1.

a Chest X-ray showing non-homogenous opacities involving right lower zone and left upper zone. b Repeat chest x-ray showed partial resolution of lung infiltrates

Fig. 2.

Contrast enhanced CT scan of chest showing bilateral lower lobe consolidations

Fig. 3.

a Fine needle aspiration cytology smear of lung lesion shows discrete immature lymphoid cells. (May Grunwald Giemsa stain X 240). b Aspiration cytology smear shows large lymphoid cells with scanty cytoplasm and moderately pleomorphic nuclei (Hematoxylin and eosin stain X 420)

Extra-nodal involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma is common; 40–50% cases have ubiquitous extra-nodal involvement, most common site being skin and gastrointestinal tract [3]. Presence of extra-nodal disease is generally associated with poor performance status and poor tolerance to standard chemotherapy resulting in poor outcome. In addition, particular anatomical sites have been described to be independently associated with the outcome. Lungs can be involved in up to 40% patients of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (mostly secondarily); Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma are the commonest high grade NHLs that involve lungs, mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is the commonest low grade NHL that involve lungs [4, 5]. Pulmonary involvement is mostly reported in the form of lung nodules, mass or pleural effusion. However, pulmonary involvement by DLBCL mimicking non-resolving pneumonia is rarely reported [6]. Assessment of pulmonary function is not necessary before NHL therapy, however, care should be taken as drugs (e.g. Rituximab) [7] used in treatment of NHL have been reported to cause severe pulmonary injury in otherwise healthy lungs.

Lung infections are always a close differential diagnosis; they are not only more common but also pose challenge to institution of chemotherapy in a timely manner. It is always imperative to rule out chest infections before starting chemotherapy because subsequent myelosuppression can be catastrophic. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis is useful in not only excluding infections but an added immunocytochemistry may at times be confirmative of maliganancy. However, whenever possible, secondary lymphomatous lung involvement should be confirmed by histopathology and immunohistochemistry on biospy.

Index case emphasises the fact that pulmonary signs and symptoms in NHL patients with B symptoms not responding to standard antibiotic therapy must be evaluated comprehensively. A high index of suspicion of secondary lymphomatous involvement can clinch the diagnosis early preventing unnecessary delay in administering chemotherapy. In the index case, despite the presence of respiratory failure at presentation, the institution of full dose chemotherapy (after confirmation of lymphomatous lung involvement) produced dramatic clinical and radiological improvement. Therefore, not all cases of NHL with poor performance status need truncation of chemotherapy doses. Therefore, not all cases of NHL with poor performance status need truncation of chemotherapy doses. Irrespective of extra-nodal involvement and performance status, there is always a need to implement therapy urgently, when diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma because the disease itself can be contributing to the poor performance status of the patient and if we do not implement therapy we cannot hope for any results. A decision to give a prephase therapy in high volume disease and in poor performance status patient for initial control prior to instituting definitive therapy should be individualized. Lastly, the lung involvement in the index case responded dramatically to R-CHOP chemotherapy, which is the standard protocol. However, we may have to be discerning in select situations while deciding the appropriate chemotherapy regimen.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed signed written consent was taken from the patient involved.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and Animals Rights

No animals were involved in the study.

References

- 1.Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117(19):5019–5032. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-293050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sehn LH, Gascoyne RD. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: optimizing outcome in the context of clinical and biologic heterogeneity. Blood. 2015;125(1):22–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurney KA, Cartwright RA. Increasing incidence and descriptive epidemiology of extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma in parts of England and Wales. Hematol J. 2002;3:95–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra P. Hematopoietic and lymphoid neoplasm of lungs. In: Jindal SK, editor. Text book of pulmonary medicine: a developing countries perspective. 1. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mian M, Wasle I, Gritsch S, et al. B cell lymphoma with lung involvement: what is it about? Acta Haematol. 2015;133(2):221–225. doi: 10.1159/000365778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J, Park H, Kim YW, Yoo CG. Pulmonary lymphoma misdiagnosed as pneumonia. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2016;32(4):509–511. doi: 10.1007/s12288-016-0702-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahu KK, Badhala P, Malhotra P, Aggarwal AN. A rare case of rituximab induced interstitial lung disease. Lung India. 2016;33(4):472–473. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.184960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]