Abstract

Objective

College students are an at-risk population for heavy drinking and negative alcohol-related outcomes. Research has established that brief, multi-component, motivational interviewing-based interventions can be effective at reducing alcohol use and/or related problems, but less is known about the efficacy of individual components within these interventions. The purpose of this study was to test the efficacy of two single-component, in-person brief (15-20 minute) alcohol interventions: personalized normative feedback (PNF) and protective behavioral strategies feedback (PBSF).

Method

Data were collected on 366 undergraduate students from a large, Midwestern university (65% women, 89% White) who were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: PNF, PBSF, or alcohol education (AE). Participants completed measures of alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, social norms, and protective behavioral strategies.

Results

Results indicated that the PNF intervention was effective relative to the other conditions at reducing alcohol use, and that its effects at six-month follow-up were mediated by changes in perceived norms at the one-month follow-up. The PBSF intervention was not efficacious at reducing alcohol use or alcohol-related problems.

Conclusions

These findings provide support for the efficacy of an in-person PNF intervention, and theoretical support for the hypothesized mechanisms of change in the intervention. Implications for researchers and clinicians are discussed.

Keywords: Brief Intervention, Motivational Interviewing, Social Norms, Protective Behavioral Strategies, College Drinking

Heavy drinking among college students is an important public health concern. National epidemiological studies have shown approximately 40% of college students reported “binge” drinking (i.e., 5+/4+ drinks for men/women in one sitting) in the preceding two weeks (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2010), and one national study of college freshman found approximately 20% of men and 8% of women reported consuming at least double the binge drinking threshold at least once in the preceding two weeks (White, Kraus, & Swartzwelder, 2006). Other research has reported that approximately 20% of college students met diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004). Finally, one study estimated that over the course of one year approximately 1,800 deaths, 600,000 unintentional injuries, and 650,000 physical or sexual assaults among college students could be attributed to alcohol use (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). These findings highlight the importance of identifying effective alcohol intervention and prevention strategies among the college student population.

Brief Interventions for College Student Drinking

The most commonly studied individual interventions in the college drinking literature are brief motivational interventions (BMIs) that also include personalized drinking feedback. The most popular format for BMIs is modeled after the BASICS intervention developed by Alan Marlatt and his colleagues (Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999; Marlatt et al., 1998). The student first completes a series of questionnaires on his or her drinking habits, which are then used to create personalized feedback that is reviewed in a one-on-one meeting with a clinician typically 45-50 minutes in length. The specifics of the feedback vary from study to study, but commonly included components include social norms information, alcohol-related risks based on one's drinking behaviors, a summary of alcohol-related problems experienced, family history of alcoholism, dollars spent on alcohol, caloric intake from alcohol, and alcohol-related expectancies (e.g., Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2006; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, & Jouriles, 2009). The purpose of the feedback is to highlight the student's current risky drinking habits, help increase dissonance regarding actual and perceived behaviors, and resolve ambivalence about changing behavior. BMIs are conducted in a Motivational Interviewing (MI)-based style (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), in that the clinician adopts a nonjudgmental, empathic stance but nonetheless focuses on helping the student change his or her drinking behaviors.

A number of clinical trials have examined the efficacy of BMIs modeled after the BASICS intervention, with results generally showing positive effects relative to control conditions. Comprehensive qualitative reviews (e.g., Cronce & Larimer, 2011) have consistently concluded that in-person BMIs were efficacious relative to control conditions, and a meta-analysis of individual college drinking interventions found that interventions delivered via MI and included personalized feedback were more effective than other types of interventions (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007). This finding is consistent with meta-analytic reviews of the larger alcohol treatment research literature that support the positive effects of MI-based treatments (e.g., Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003).

One important limitation to the research on the efficacy of BMIs among heavy drinking college students is that relatively little is known regarding the efficacy of specific components or content areas of the interventions. Research has shown that BMIs that include multiple content areas are efficacious at reducing alcohol-related risks among college students, but it is possible that only some aspects of the intervention contribute to positive outcomes. For example, it could be that discussing social norms information impacts subsequent decisions to use alcohol, whereas reviewing dollars spent on alcohol has no effects. One strategy for addressing this limitation is to examine the efficacy of brief interventions that only focus on a single content area. If such single component BMIs were shown to be efficacious, this would suggest that the content covered in the intervention is an active intervention ingredient. In the present study we focused on two commonly included content areas: descriptive social norms and use of protective behavioral strategies.

Descriptive Social Norms

Descriptive norms refer to perceived quantity and/or frequency of alcohol use among a specific reference group (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006). To integrate descriptive norms into a BMI, individuals answer questions about their own level of drinking as well as perceived drinking among a “typical” member of a reference group (e.g., college students nationwide). The individual is then provided with personalized feedback that details (a) how his/her drinking compares to the actual drinking norms, and (b) how his/her perceptions of drinking among the typical student compares to the actual norms. Typically, heavy drinking students perceive that their drinking is below the norm, when in fact both their own alcohol use and their perceived norms are well above the actual norms (Borsari & Carey, 2003). The salience of the normative group and discrepancy between actual and perceived behavior is thought to motivate behavior change (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006).

Several clinical trials have examined the efficacy of brief interventions for college student drinking that only include personalized content on descriptive social norms (Personalized Normative Feedback [PNF]: e.g., Lewis, Neighbors, Oster-Aaland, Kirkeby, & Larimer, 2007; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004; Neighbors, Lewis, Bergstrom, & Larimer, 2006). Participants in these studies reviewed their personalized feedback, but did so in the absence of contact with a clinician. Results from these trials have provided consistent support for the efficacy of PNF at reducing alcohol use among heavy drinking college students. An important limitation to the research on PNF interventions, though, is that their effects have not been compared to alternative interventions also designed to reduce alcohol consumption. The effects of PNF among college students have primarily been compared to assessment-only control conditions. Further, researchers have yet to evaluate the effects of in-person PNF-only interventions among heavy drinking college students.

Protective Behavioral Strategies (PBS)

PBS are specific cognitive-behavioral strategies that are designed to limit or eliminate alcohol use and related consequences (Martens et al., 2004). Example strategies from a commonly used measure include avoiding drinking games, stopping drinking at a predetermined time, and using a designated driver (Martens et al., 2005). PBS have clear theoretical relevance for intervention efforts among college students, and a number of studies have showed that higher levels of PBS use were associated with less alcohol use and fewer alcohol-related problems (e.g., Benton et al., 2004; Martens et al., 2004; 2005; 2007).

Although earlier clinical trials of BMIs did not include specific content on PBS, more recent trials have included the construct in the form of personalized feedback (e.g., Martens, Kilmer, Beck, & Zamboanga, 2010) or via encouragement to consider using certain strategies (e.g., Larimer et al., 2007). Researchers have not examined the efficacy of an intervention focusing exclusively on PBS, but two studies have shown that changes in PBS use mediated the long-term effects of multi-component BMIs (Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007; Larimer et al., 2007). These findings provide some support for the potential causal role of PBS in the context of brief interventions among college students, which include other motivational components, but they do not answer the question of whether or not PBS can be an efficacious intervention when delivered independently. Research has shown that behavioral self-control training treatments, which are conceptually similar to an intervention focusing primarily on PBS, demonstrate significant treatment effects (Walters, 2000). Such treatments, though, are considerably longer than the PBS-based intervention examined in the present study.

The Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to advance the understanding of the effects of specific content areas delivered in the context of a BMI, namely descriptive social norms and PBS, at reducing alcohol use and related problems. It is important to note the way in which each content area theoretically impacts subsequent alcohol use differs between the two. Addressing descriptive social norms is thought to change drinking behavior by correcting an individual's belief that others drink more than they actually do, which results subsequent reductions in one's own drinking behaviors. In contrast, addressing PBS use in an intervention is thought to impact subsequent drinking behaviors by teaching, encouraging, and/or motivating the individual to engage in strategies that will result in less alcohol use and fewer alcohol-related problems. Thus, we hypothesized that participants who received a one-on-one BMI focusing exclusively on PNF or protective behavioral strategies feedback (PBSF) would report less alcohol use and fewer alcohol-related problems at follow-up than those receiving a one-on-one session focusing on general alcohol education. We also compared effects between the PNF and PBSF conditions, but did not have a priori hypotheses about the effects of the interventions relative to each other.

Method

Design

In this randomized controlled trial participants from a large, public university were assigned to one of three in-person conditions: PNF, Protective Behavioral Strategies Feedback (PBSF), or Alcohol Education (AE). Participants were randomized, stratified by gender, via a random number table and provided self-report assessment data at three time-points: baseline, one-month follow-up, and six-month follow-up.

Participants and Procedure

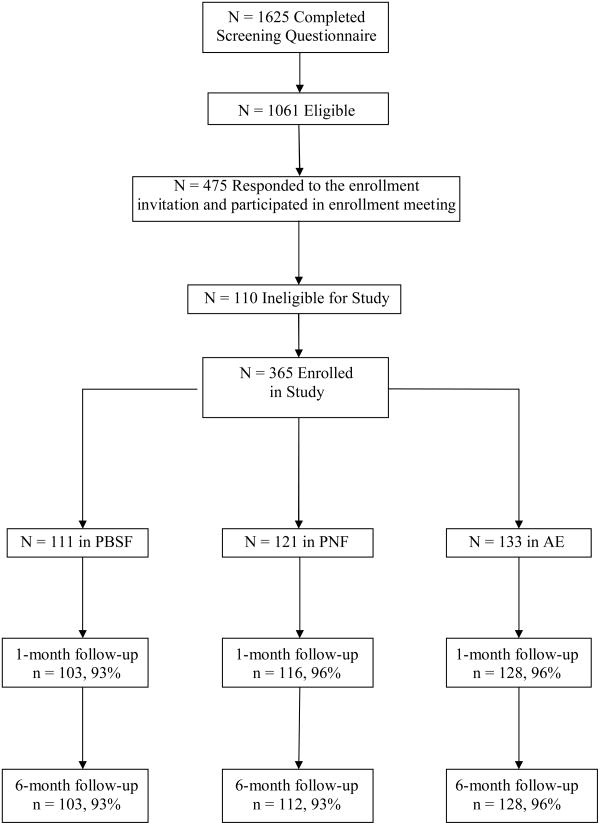

We conducted an a priori power analysis to determine the necessary sample size for this trial. Based on prior brief intervention trials in the college drinking literature we estimated a population effect size (Cohen's d) of .35. Assuming α = .05, approximately 310 participants were necessary to achieve a power of .80 for identifying overall between-group differences on an outcome variable. Students were eligible to participate in the study if they reported at least one binge drinking episode (5+/4+ drinks in one sitting for men/women) in the preceding 30 days and did not report meeting criteria for alcohol dependence, excessive drug use (20+ days in the preceding month), or elevated depression symptoms. Figure 1 summarizes the flow of participants into the trial. Four hundred seventy-five students responded to our invitation to participate in the intervention phase of the study. One hundred ten students were ineligible because they self-reported symptoms consistent with alcohol dependence, heavy drug use, and/or depressive symptoms, and were provided a referral to the university counseling center. This left a final sample of 365.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Diagram. PBSF = Protective Behavioral Strategies Feedback; PNF = Personalized Normative Feedback; AE = Alcohol Education

Students were recruited via an email announcement over the university's mass communication system that invited students to participate in a study on “health behaviors and alcohol use.” Those who were interested in participating were directed to follow a link that took them to our online alcohol screening questionnaire. One thousand six hundred twenty five students completed the questionnaire, 65% of whom (N = 1025) met our initial eligibility criteria and were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in the next phase of the study. Interested participants were scheduled to come to our on-campus laboratory for an enrollment meeting. Recruitment efforts were ceased once we filled all of our available scheduling slots for participant enrollment and intervention delivery. After completing the informed consent questionnaire participants completed the additional eligibility screening questionnaires assessing for the presence of alcohol dependence, regular drug use, and elevated depressive symptoms. Ineligible students were informed of the reason for their ineligibility and provided a referral to the university counseling center. All eligible individuals completed the baseline battery of questionnaires, were randomly assigned to one of the three intervention conditions, and completed their intervention. Participants were compensated with a $25 gift card after completing their baseline assessment and intervention and after completing each follow-up assessment. Prior to participant recruitment this study was approved by the university IRB where the study was conducted. The study has also been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT01168726).

Measures

Screening measures

Participants completed a single item measure asking them to indicate the most number of drinks they consumed on a single occasion in the preceding 30 days. The commonly used criteria of 5+ drinks for men and 4+ drinks for women was used to assess for the presence of binge drinking (Courtney & Polich, 2009). Potential alcohol dependence was assessed via a self-report checklist where participants indicated via yes/no responses if they had experienced each of the alcohol dependence criteria over the preceding 12 months. This checklist was modeled after measures used in other studies in the college drinking literature (Simons, Carey, & Willis, 2009). Participants who endorsed at least three symptoms were considered positive for potential alcohol dependence. Drug use in the past 30 days was assessed via a single item measure asking the participant to indicate the number of days in the past 30 in which he/she used illicit drugs. Prior studies in the college drinking intervention literature have excluded students for “near daily” drug use (e.g., White H. R. et al., 2006), which we operationalized as 20+ days in the current study. Finally, to assess for depressive symptoms participants completed the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D: Radloff, 1977). Consistent with research evaluating the optimal cut-point for high sensitivity and specificity among college students (Shean & Baldwin, 2008), a cutoff score of 21 was used to indicate elevated depressive symptoms.

Alcohol consumption

Our primary outcome measures of alcohol consumption were average drinks per week, average number of drinking days per week, and peak blood alcohol concentration (BAC). We used a modified Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ: Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) to assess for average number of drinks per week and drinking days per week. After being provided with a definition of a standard drink, participants were asked to indicate how many drinks they typically consumed on each day of the week over the past 30 days. Responses were summed to provide an estimate of typical drinks consumed per week and typical drinking days per week. To calculate peak BAC we asked participants to report the most number of drinks they had consumed in a single occasion in the preceding 30 days and over how many hours they drank alcohol on that occasion, and used a standard formula to estimate BAC (Matthews & Miller, 1979). Any participant reporting greater than 50 drinks per week was re-coded to 50 drinks, while a peak BAC greater than .50 was re-coded to .50, in order to limit the influence of extreme outliers on the data. For our primary outcomes analysis we created an alcohol composite score by standardizing and summing our three alcohol use measures. Such composite measures have been used in prior trials of college drinking interventions (e.g., Larimer et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2004).

Alcohol-related problems

We used the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI: White & Labouvie, 1989) to assess for alcohol-related problems. The RAPI is a 23-item measure designed to assess for a variety of problems associated with alcohol use among adolescents. Example items include neglecting responsibilities, having an argument with friends or family, and missing school or work. Participants were asked to estimate how many times over the preceding 12 months they experienced each problem, with responses scored on a five-point scale (0 =never; 4 = 10 or more times). Results from prior studies among college students have generally shown that scores on the measure are internally consistent and associated in the expected direction with various alcohol-related constructs (Devos-Comby & Lange, 2008). In the current study the internal consistency ranged from .83 (baseline) to .87 (six-month follow-up).

Descriptive norms

We assessed descriptive drinking norms, or perceptions of drinking rates among other college students, with the Drinking Norms Rating Form (DNRF: Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991). The format of the DNRF is identical to that of the DDQ, except respondents indicate their perception of typical number of drinks consumed on each day of the week for a particular reference group. In the present study participants completed the DNRF for four reference groups: the typical male college student nationwide, the typical female college student nationwide, the typical male student at the university where the study was being conducted, and they typical female student at the university where the study was being conducted. Participants in the PNF condition received personalized feedback that included average drinks per week and average drinking days per week for the four aforementioned reference groups. The DNRF is commonly used in studies evaluating the efficacy of PNF interventions (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2004; 2006).

Protective behavioral strategies

Protective behavioral strategies were assessed with two measures: the Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale (PBSS: Martens et al., 2005; 2007) and the Drinking Control Strategies Scale (DCSS: Sugarman & Carey, 2007). The PBSS is a 15-item measure that asks participants to indicate “the degree to which you engage in the following behaviors when using alcohol or ‘partying’,” with responses scored using a six-point scale (0 = never; 6 = always). The PBSS is comprised of three subscales: Stopping/Limiting Drinking (SLD: 7 items, e.g., “Alternating alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks”), Manner of Drinking (MOD: 5 items, e.g., “Avoid drinking games”), and Serious Harm Reduction (SHR: 3 items, e.g., “Use a designated driver”). The DCSS is a 21 item measure that asks participants to indicate use of specific drinking control strategies over the preceding two weeks, with responses recorded on a six-point scale (0 = none; 5 = six or more times). The DCSS contains three factors: Selective Avoidance (7 items, e.g., “Refusing drinks”), Strategies While Drinking (10 items, e.g., “Eating before and while you are drinking”), and Alternatives (4 items, e.g., “Finding other ways besides drinking to reduce stress”). Research has shown that the Strategies While Drinking subscale was positively associated with alcohol use (Sugarman & Carey, 2007). Thus, only the Selective Avoidance and Alternatives subscales were used in this study, as encouraging the use of items from the Strategies While Drinking subscale might inadvertently promote alcohol use. In the present sample internal consistency estimates for the full PBSS, SLD, MOD, and SHR subscales across the three time-points were .81-.84, .76-.79, .68-.74, and .49-.60, respectively. Internal consistency estimates for all 11 DCSS items, the Selective Avoidance, and Alternative subscales across the three time-points were .86-.88, .82-.85, and .76-.79, respectively.

Demographics

Participants complete a brief measure that assessed basic demographic information, such as gender, ethnicity, age, year in school, and fraternity/sorority affiliation.

Interventions

Common Components to PNF and PBSF

The format of the PBSF and PNF interventions are modeled on the BASICS intervention (Dimeff et al., 1999), in that they involved the delivery of personalized feedback in MI-based framework. In the full BASICS intervention facilitators provide participants with personalized feedback across several domains; in the current study the feedback was shortened and focused on a single component in each condition, either descriptive drinking norms or protective behavioral strategies, thereby shortening the intervention to only 15-20 minutes.

Personalized Normative Feedback (PNF)

In the PNF condition the facilitator began by orientating the participant to the purpose of the session, indicating that the goal of the intervention was to discuss how the participant's own drinking and perception of typical drinking among other students compared to actual drinking norms. The facilitator then presented participants with a handout that specified two types of alcohol use measures (drinks per week and typical drinking days per week) for two different reference groups (college students nationwide and students at the university where the study was being conducted). For each feedback component participants were provided the following information: (a) their self-reported alcohol use, (b) their perceptions of alcohol use among the typical male and typical female student, and (c) actual alcohol use among the typical male and female student. Participants were also provided a percentile rank based on their drinks per week. The components were covered in the following order: drinks per week for students nationwide, drinking days per week for students nationwide, drinks per week for students at the study institution, drinking days per week for students at the study institution. The facilitator addressed the participant's reaction to each component using MI strategies. The session concluded with a summary addressing overall reaction to the session. If participants expressed an interest in changing their drinking behaviors facilitators were encouraging, but in order to avoid intervention contamination they were instructed to not address specific strategies for changing behavior.

Protective Behavioral Strategies Feedback (PBSF)

In the PBSF condition the facilitator also began the session by indicating that its overall goal was to discuss strategies that minimized harmful effects that can occur due to alcohol use. After asking an initial open-ended question about current use of PBS, the facilitator presented the participant with personalized protective behavioral strategies feedback, which formed the core of the intervention and was based on responses to the PBSS and DCSS. They first received personalized feedback on those strategies that they reported regularly using, which were any PBSS item that they at least “occasionally” used and any DCSS item they reported using at least once in the preceding two weeks. The facilitator used MI strategies to help the participant discuss how he/she implemented these behaviors and encouraged him/her to continue to use them. Facilitators next provided participants with personalized feedback on those strategies not currently being used (items that were “never” or “rarely” used on the PBSS and items on the DCSS not used in the past two weeks). They were taught to present these strategies in a non-judgmental manner, inviting participants to consider whether or not they would like to discuss the possibility of increasing their use. The facilitator and participant then discussed options for increasing the behaviors that the participant expressed in an interest in using. The session concluded with a summary of the material covered and overall reactions to the session.

Alcohol Education (AE)

The purpose of the AE control session was to provide the participant with educational information about alcohol's potentially harmful effects on different parts of the body. This condition was delivered in a didactic rather than MI-style. The participant was told that the overall goal of the session was to learn more about alcohol and its effects on the body, and the facilitator proceeded with a didactic presentation on this topic. The facilitator addressed topics such as how alcohol enters the bloodstream, effects of alcohol on the brain (e.g., depressant properties, impact on memory), and effects of alcohol on other parts of the body (e.g., heart, kidney). The participant received a handout that helped to structure the conversation. The facilitator periodically checked for comprehension, but did not encourage any personal disclosure of alcohol use.

Facilitator Training and Supervision

All facilitators on this project were graduate students in counseling or clinical psychology. They received copies of a MI textbook (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) and the intervention manuals that were developed by the project PI (MPM) and Co-I (JGM). After reading these materials, they engaged in a 20-hour training protocol that included the following components: (a) background readings on college student drinking, (b) a half-day workshop on MI provided by an expert in the area (JGM), (c) viewing commercial tapes on the delivery of MI, and (d) completing taped practice sessions for each condition. Facilitators were trained to deliver all three interventions in order to minimize the possibility of therapist effects impacting project outcomes (e.g., Wampold & Brown, 2005). The project PI (MPM) provided written and in-person feedback on the practice sessions, and facilitators did not see participants until in the PI's judgment they could adequately deliver each intervention condition. Interventions were audio-taped and reviewed during weekly group supervision meetings. Random samples of sessions from each clinician were coded both for protocol adherence and overall MI-consistent behavior by blind, independent raters (discussed below).

Data Analytic Plan

All analyses were conducted in an intent-to-treatment framework. Comparisons among conditions at the follow-up points were assessed via mixed-model ANOVA where we examined the group X time interaction on each dependent variable. Gender was also included as an independent variable to control for its effects and assess for the possibility of gender X intervention interactions. We first examined intervention effects on descriptive social norms and protective behavioral strategies, followed by intervention effects on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol use and problems were assessed in separate analyses because prior intervention studies among college students have shown differential effects between use and problems (e.g., Larimer et al., 2007; Marlatt et al., 1998). Planned contrasts were conducted among the conditions in order to assess for differences between specific interventions on our dependent variables of interest. Tests of mediation involved examining the magnitude of the hypothesized indirect effects.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Sample demographics and baseline alcohol use

The majority of the participants in the study were women (65.2%) and White (89.2%). Class status was relatively equal: 25.2% of the sample identified themselves as freshmen, 18.6% as sophomores, 29.9% as juniors, and 26.3% as seniors (including fifth year+). The mean age of the sample was 20.10 years (SD = 1.35). Approximately one-fourth of the sample reported being active members in a fraternity or sorority (25.2%). Demographic characteristics by condition are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences across the three conditions on any demographic characteristic. At baseline participants reported consuming an average of 15.75 (SD = 10.79) drinks per week, an average of 2.86 (SD = 1.24) drinking days per week, an average peak BAC of .162 (SD = .106), and an average score of 10.75 (SD = 8.34) on the RAPI (see Table 1). There were no significant differences across the three conditions on baseline alcohol use or alcohol-related problems.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics by Condition.

| Intervention Condition | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBSF | PNF | AE | |||||||

| n = 111 | n = 122 | n = 133 | |||||||

| Variable | % | M | SD | % | M | SD | % | M | SD |

| Men | 26 | 41 | 36 | ||||||

| Women | 74 | 59 | 64 | ||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 88 | 92 | 88 | ||||||

| African American | 4 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Asian/Asian American | 2 | 2 | 6 | ||||||

| Native American | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Other | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||||||

| Year in School | |||||||||

| Freshman | 30 | 25 | 22 | ||||||

| Sophomore | 18 | 20 | 18 | ||||||

| Junior | 23 | 31 | 34 | ||||||

| Senior | 29 | 24 | 26 | ||||||

| Fraternity/Sorority Member | |||||||||

| Yes | 25 | 26 | 25 | ||||||

| No | 75 | 74 | 75 | ||||||

| Age (years) | 19.95 | 1.36 | 20.12 | 1.38 | 20.20 | 1.31 | |||

| Alcohol Variables | |||||||||

| Drinks/Week | 15.46 | 11.10 | 15.27 | 10.80 | 16.41 | 10.55 | |||

| Drinking Days/Week | 2.97 | 1.32 | 2.79 | 1.28 | 2.82 | 1.14 | |||

| Peak BAC | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.11 | |||

| RAPI Scores | 10.51 | 7.72 | 9.74 | 7.87 | 11.87 | 9.13 | |||

Note. PBSF = Protective Behavioral Strategies Feedback. PNF = Personalized Normative Feedback. AE = Alcohol Education. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index.

Sample attrition

Overall follow-up rates were 95% at the one-month follow-up and 94% at the 6-month follow-up (see Figure 1). There were no significant differences across conditions in terms of rates of follow-up. There were no baseline differences on the demographic characteristics, number of drinking days, or RAPI scores between those who did and did not complete the follow-ups. Those who did not provide follow-up data at one-month reported more drinks per week (20.72 vs. 15.49, p = .04) and a higher peak BAC (.221 vs. .159, p = .02) than those who did provide follow-up data.

Intervention fidelity

Twenty percent of the sessions from each intervention condition were randomly selected to be coded for intervention fidelity. We used a brief intervention adherence protocol that has been used in prior clinical trials (Barnett et al., 2007; Murphy et al., 2010; in press). Coders were masters level clinicians who had prior MI and brief intervention training, but who were not involved in the current project. The interventions were coded on several components, including properly introducing the session, coverage of different aspects of the feedback (for PNF and PBSF) or educational information (for AE), and session summary/conclusion. The PNF and PBSF sessions were also coded for competence of 10 basic MI skills (e.g., reflecting listening, developing discrepancy: Barnett et al., 2007). Each item on the coding sheet was rated as a 1 (Did it poorly or didn't do it but should have), 2 (Meets Expectations), or 3 (Above Expectations). A score of 2 or higher indicated that the intervention component was delivered in a satisfactory manner. Finally, sessions were coded for contamination with other conditions.

Results indicated satisfactory adherence to the intervention protocols. All components of the intervention had a mean rating of 2 or greater, with the exception of the rating for introducing the PNF session (M = 1.95, Mdn = 2.00, SD = 0.22). The mean ratings for the MI-specific skills were 2.12 (PNF) and 2.21 (PBSF). The percentage of components for each intervention rated as 2 or greater ranged from 94% to 100%. These ratings indicated that in general facilitators demonstrated competence in both covering the specific components of each session and demonstrating overall MI-specific behaviors. No sessions were rated as experiencing contamination with a different condition.

Therapist effects

To assess for therapist effects we conducted separate repeated measures ANCOVA on the alcohol use composite variable and alcohol-related problems, controlling for intervention condition. Results indicated that there was no time X clinician effect for alcohol use, Wilks' λ = .93, F(28,694) = 0.89, p = .63, a finding that was consistent when examining a subset of seven clinicians who conducted the largest number of sessions (n > 20), Wilks' λ = .95, F(12,516) = 0.36, p = .36. There were time X clinician effects for alcohol-related problems both for all clinicians, Wilks' λ = .89, F(28,694) = 1.51, p = .04, and for the subset who conducted the largest number of sessions, Wilks' λ = .89, F(12,516) = 2.58, p < .01. However, pairwise contrasts on alcohol-related problems indicated that changes in alcohol-related problems did not significantly differ between any two clinicians (p >.15.) Therefore, we concluded there were no meaningful therapist effects and collapsed our analyses across therapists.

Intervention Effects on Social Norms and Protective Behavioral Strategies

We first examined intervention effects on theoretical mechanisms of change of the PNF and PBSF interventions, namely perceived norms and use of PBS. Because all participants provided normative estimates for each social norms reference group, we created a social norms composite variable by standardizing and summing the four descriptive norms variables. Results indicated a significant group X time interaction on this variable, Wilks' λ = .63, F(4,716) = 46.40, p < .001. Gender did not moderate the intervention effect (p = .29). Post-hoc between-condition tests indicated significant differences between participants in the PNF condition and those in both the PBSF and AE conditions. Means, standard deviations, and within-person effect sizes for each condition are presented in the top panel, Table 2. Participants in the PNF condition reported a large decrease in perceived drinking among other students at both the one- and six-month follow-up, while those in both PBSF and AE conditions reported a large increase in perceived drinking among other students at both follow-ups.

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Within-Person Effect Sizes (Cohen's d) on Social Norms and PBS by Condition.

| Variable | Baseline | One-Month | Six-Month | One-Month Effect | Six-Month Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Norms | |||||

| PNF | 0.01 (3.63) | -2.85 (2.74) | -2.71 (2.57) | -1.78** | -1.70** |

| PBSF | 0.12 (3.91) | 1.51 (3.87) | 1.52 (3.52) | 1.24** | 1.23** |

| AE | -0.10 (1.34) | 1.34 (3.19) | 1.20 (3.79) | 1.09** | 0.81** |

|

| |||||

| PBSS Scores | |||||

| PNF | 11.98 (2.04) | 12.30 (2.12) | 12.14 (2.24) | 0.52** | 0.18 |

| PBSF | 11.97 (1.79) | 12.63 (1.97) | 12.41 (1.94) | 0.97** | 0.54** |

| AE | 11.45 (1.98) | 11.47 (1.86) | 11.44 (2.01) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| DCSS Scores | |||||

| PNF | 5.39 (1.82) | 5.47 (1.92) | 5.34 (1.92) | 0.11 | -0.06 |

| PBSF | 5.59 (1.71) | 5.71 (1.78) | 5.71 (2.09) | 0.16 | 0.13 |

| AE | 5.40 (1.73) | 5.33 (1.83) | 5.18 (1.74) | -0.11 | -0.31 |

Note. PBSF = Protective Behavioral Strategies Feedback. PNF = Personalized Normative Feedback. AE = Alcohol Education. PBSS = Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale. DCSS = Drinking Control Strategies Scale. Standard deviations are in parentheses. Social norms values are standardized scores. PBSS and DCSS scores are the sum of the subscale scores.

p < .01.

To assess for intervention effects on PBS use we conducted separate tests on summary scores of the PBSS and DCSS. Results indicated a significant group X time interaction on the PBSS summary score, Wilks' λ = .97, F(4,716) = 2.48, p = .04. Gender did not moderate the intervention effects (p = .50). Post-hoc between-condition tests indicated significant differences between participants in both the PBSF and PNF conditions and those in the AE condition (see Table 2, second panel). Participants in the PBSF condition reported significant increases in PBS use at both the one- and six-month follow-up, while those in the PNF condition reported increases at the one-month, but not six-month, follow-up. PBS use did not change in the AE condition. In contrast, there were no between-group differences on the DCSS summary score, Wilks' λ = .99, F(4,716) = 0.92, p = .45. There were also no within-condition changes on DCSS scores, and gender did not moderate the intervention effect (p = .75). These findings indicate that the PBSF condition, and to some degree the PNF condition, was effective at increasing PBS use only as measured by the PBSS.

Intervention Effects on Alcohol use and Alcohol-Related Problems

We first examined between-group effects on the alcohol composite variable, with results indicating a significant group X time interaction, Wilks' λ = .95, F(4,716) = 4.83, p = .03. Gender did not moderate the intervention effect (p = .40). Post-hoc between-condition tests indicated significant differences between participants in the PNF condition and those in the other conditions. Within-participant differences for each alcohol use measure (drinks per week, drinking days per week, peak BAC) by condition are presented in the first three panels of table 3. Participants in the PNF condition reported significant decreases on all three measures at both follow-ups. Those in the PBSF and AE conditions reported significant decreases in drinks per week and peak BAC, but effects were considerably smaller than for participants in the PNF condition. Those in the PBSF and AE conditions did not report significant changes in drinking days per week.

Table 3. Means, Standard Deviations, and Within-Person Effect Sizes (Cohen's d) on Alcohol Use and Alcohol-Related Problems by Condition.

| Variable | Baseline | One-Month | Six-Month | One-Month Effect | Six-Month Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinks Per Week | |||||

| PNF | 15.27 (10.80) | 10.14 (8.90) | 9.57 (8.78) | -1.15** | -1.16** |

| PBSF | 15.46 (11.10) | 13.61 (10.41) | 12.55 (8.96) | -0.55** | -0.68** |

| AE | 16.41 (10.55) | 14.49 (10.52) | 13.74 (10.77) | -0.51** | -0.64** |

|

| |||||

| Drinking Days Per Week | |||||

| PNF | 2.79 (1.28) | 2.31 (1.35) | 2.27 (1.41) | -0.81** | -0.77** |

| PBSF | 2.97 (1.32) | 2.86 (1.34) | 2.83 (1.40) | -0.20 | -0.22 |

| AE | 2.82 (1.14) | 2.88 (1.29) | 2.74 (1.54) | 0.11 | -0.13 |

|

| |||||

| Peak BAC | |||||

| PNF | .154 (.102) | .107 (.097) | .111 (.089) | -1.01** | -0.89** |

| PBSF | .158 (.104) | .129 (.100) | .133 (.113) | -0.78** | -0.54** |

| AE | .173 (.109) | .152 (.104) | .144 (.111) | -0.51** | -0.62** |

|

| |||||

| RAPI Scores | |||||

| PNF | 8.73 (7.87) | N/A | 7.76 (9.42) | N/A | -0.32 |

| PBSF | 9.51 (7.71) | N/A | 7.68 (7.25) | N/A | -0.64** |

| AE | 10.87 (9.13) | N/A | 8.91 (9.17) | N/A | -0.54** |

Note. PBSF = Protective Behavioral Strategies Feedback. PNF = Personalized Normative Feedback. AE = Alcohol Education. BAC = Blood Alcohol Concentration. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index. Standard deviations are in parentheses.

p < .01.

We next examined between-group effects on alcohol problems as measured by RAPI total scores. Because the RAPI assessed alcohol-related problems over a relatively long time frame (past 12 months), we only assessed for differences between baseline and six-month follow-up. Results indicated that the group X time interaction was not statistically significant, Wilks' λ = 1.00, F(2,359) = 0.35, p = .70. Gender did not moderate the intervention effect (p = .43). Within-participant differences are presented in the bottom panel of Table 3. Alcohol-related problems decreased across all three conditions, with the largest decrease occurring in the PBSF and AE conditions.

Tests of Mediation

To test for mediation we used the PROCESS tool for SPSS (Hayes, under review). PROCESS was used to calculate the magnitude of the hypothesized mediated effect, and bootstrapping with 10,000 cases was used to examine the statistical significance of the effect. We first examined a model where intervention condition (PNF vs. PBSF and AE) was the independent variable, the one-month social norms composite variable was the mediator variable, and the six-month alcohol use composite variable was the dependent variable. The partially standardized indirect effect, which is interpreted in terms of standard deviation of the dependent variable (Preacher & Kelley, 2011), was statistically significant: β = .59, 95%CI (.46,.73), R2med = .03. The direct effect of intervention condition on six-month alcohol use was non-significant with one-month social norms in the model.

We next examined a mediated model that included both social norms and protective behavioral strategies (as measured by PBSS total scores). We did so in order to determine if the PNF effect could be attributed specifically to changes in perceived norms and not an additional factor that could also plausibly change over time. Results of this analysis indicated that a mediated effect of intervention condition on alcohol use existed through social norms, B = 1.36, 95%CI (1.01,1.77), but not through PBSS scores, B = 0.10, 95%CI (-0.04,0.29).1 Thus, these findings indicate that the effects of the PNF condition could be attributed to changes in perceived drinking among other students.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the efficacy of two single-component brief alcohol interventions, PNF and PBSF, at reducing alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among a sample of at-risk college students. Findings from the study indicated that PNF was effective at reducing alcohol use (but not alcohol-related problems), and that its effects could be attributed to changes in perceived drinking among other students. In contrast, the PBSF intervention was not efficacious at reducing alcohol use or alcohol-related problems relative to the control condition. Implications of these findings for researchers and clinicians are discussed below.

Results from this study provide an important addition to the literature on the efficacy of PNF-only interventions (Walters & Neighbors, 2005). This was the first clinical trial to examine the efficacy of an in-person PNF. It was also a rigorous examination of PNF's effects, in that the intervention was compared to a control condition that accounted for clinical contact (AE) as well as an intervention that was hypothesized to have an active treatment effect (PBSF). Participants in the PNF condition showed greater reductions in alcohol use than those in the other conditions, and exhibited moderate to large within-person changes across multiple indices of alcohol use at both the one- and six-month follow-up. The tests of mediation also enhanced theoretical support for the hypothesized mechanism of change in PNF interventions, in that changes in alcohol use at six-month could be attributed to changes in perceived drinking among other students at one-month. These findings, though, were limited to measures of alcohol use, as PNF did not have an impact on alcohol-related problems. A similar pattern of findings has occurred in other brief intervention trials (e.g., Larimer et al., 2007; Martens et al., 2010). One possible explanation for the lack of a treatment effect on alcohol-related problems is that observed changes in alcohol-related problems take longer to emerge than changes in alcohol use itself. A second explanation is that the PNF intervention did not include norms for alcohol-related problems. Nonetheless, the findings from the present study highlight the ability of PNF to change drinking behavior, and therefore supports it use as a stand-alone intervention or aspect of a multi-component brief intervention.

In this trial the PBSF condition was not efficacious at reducing alcohol use or alcohol related problems. Findings from this study are somewhat similar to those reported by Sugarman and Carey (2009), who reported that participants instructed to increase PBS use over the following two weeks did not report significant reductions in alcohol use. Given that PBS use has been consistently shown to be associated with less alcohol and fewer alcohol-related problems (e.g., Benton et al., 2004; Martens, Pedersen, et al., 2007), these findings are likely not attributable to the content of the intervention being unrelated to the outcome variables of interest. Although the PBSF intervention did result in increases in PBS use relative to the control condition, this occurred only for strategies measured on the PBSS and not the DCSS. Further, between-group contrasts between the PBSF and PNF conditions were non-significant, even though participants in the PBSF condition reported greater within-subject changes on PBSS scores. Thus, the null findings in the PBSF condition may be attributable to the intervention not sufficiently impacting subsequent PBS use. It is possible that simply providing personalized feedback in the context of a MI intervention is not sufficient enough to impact PBS use. Perhaps more active approaches like CBT or skills-based interventions (e.g., Kivlahan et al., 1990) are necessary for change in PBS use to occur. For example, it is possible that individuals need the opportunity to learn about PBS, discuss ways to implement them, experiment with using them, and then have the opportunity to discuss these efforts with a clinician. The lack of findings for the PBSF condition also highlights the potential importance of activating motivation to change within a brief intervention. PNF interventions by definition are designed to increase motivation to change by identifying discrepancies between an individual's behavior and perceived behavior among others (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006). In contrast, the PBSF intervention did not explicitly target motivation to change, instead focusing on increasing specific behaviors associated with fewer alcohol-related risks. It may be that the targeting the former (motivation to change) is an integral precursor to targeting the latter (strategies for change).

There were several limitations to the present study. First, all data were collected from volunteer, non-treatment seeking college students at a single university and women were disproportionately represented in the sample, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, all alcohol use data were retrospective self-report and were not verified via collateral reports or physiological measures. Thus, it is possible that the intervention effects detected in this study reflect a self-presentation bias on the part of the participants. It is also possible that participants' responses were influenced by social desirability, which was not assessed in the study. In general, though, research has suggested that values from retrospective self-report assessments of alcohol use and related problems are generally reliable and valid (Martens, Arterberry, Cadigan, & Smith, in press). Third, less than one-half of those eligible to participate in the study chose to do so; in the vast majority of instances they simply did not respond to our attempts to contact them and invite them to participate. Our enrollment rate, though, was similar to other clinical trials in the college drinking literature (e.g., Larimer et al., 2007). Finally, for our measure of alcohol-related problems there was some overlap between the follow-up and baseline assessment period. This limitation is mitigated by the fact that our measure assessed for frequency of each problem as opposed to a dichotomous format where the respondent simply indicated whether or not the problem was experienced at all over the specified time frame.

Despite these limitations, this study makes in important contribution to the literature on brief alcohol interventions among at-risk college students. The findings from the study provide support for the efficacy of an in-person PNF-only intervention, which to date has not been examined in the research literature. An important future direction in this area would be to determine if an in-person PNF-only intervention provided greater effects than an intervention delivered in the absence of clinical contact (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2004). The findings also suggest that a feedback-based intervention focused solely on PBS may not in and of itself be effective at changing drinking behaviors. This does not mean that the topic of PBS should be removed from brief alcohol interventions; at least two previous clinical trials have shown that PBS use mediated the effects of multicomponent brief alcohol interventions (Barnett et al., 2007; Larimer et al., 2007). It does suggest, though, that researchers should consider alternative strategies for examining the potential effects of addressing PBS within the context of a brief intervention. One possibility for future research is to determine if addressing PBS use in an intervention is effective only after attempting to enhance motivation to change behavior. Overall, researchers know relatively little about the unique effects associated with individual components typically included in brief alcohol interventions, with the exception of PNF. We encourage researchers to conduct dismantling studies and additional examinations of single-component interventions in an effort to provide additional insight on this important question.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH grant# R21AA016779.

Footnotes

In multiple-mediator models PROCESS only provides unstandardized estimates.

Contributor Information

Matthew P. Martens, Department of Educational, School, and Counseling Psychology, University of Missouri

Ashley E. Smith, Department of Educational, School, and Counseling Psychology, University of Missouri

James G. Murphy, Department of Psychology, University of Memphis

References

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;54:54–60. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Brief motivational intervention vs. computerized alcohol education with college students mandated to intervention. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research and Health. 2011;34:210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney KE, Polich J. Binge drinking in young adults: Data, definitions, and determinants. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:142–156. doi: 10.1037/a0014414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos-Comby L, Lange JE. Standardized measures of alcohol-related problems: A review of their use among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:349–361. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students: A harm reduction approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. An analytical primer and computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling under review. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among US college students ages 18-25, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;16S:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2009: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19-45. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. NIH Publication No. 10-7585. [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:805–810. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:213–218. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Kirkeby BS, Larimer ME. Indicated prevention for incoming freshmen: Personalized normative feedback and high-risk drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2495–2508. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Arterberry BJ, Cadigan JM, Smith AE. Review of clinical assessment tools. In: Correia C, Murphy J, Barnett N, editors. College Student Alcohol Abuse: A Guide to Assessment, Intervention, and Prevention. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. pp. 115–145. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Corbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Kilmer JR, Beck NC, Zamboanga BL. The efficacy of a targeted personalized feedback intervention among intercollegiate athletes: A randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:660–669. doi: 10.1037/a0020299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Measuring alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies among college students: Further examination of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:307–315. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Taylor KK, Damann KM, Page JC, Mowry ES, Cimini MD. Protective factors when drinking alcohol and their relationship to negative alcohol-related consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:390–393. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors. 1979;4:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. 2nd. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, McDevitt-Murphy ME. Computerized versus motivational interviewing alcohol interventions: Impact on discrepancy, motivation, and drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:628–639. doi: 10.1037/a0021347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Larimer ME. Being controlled by normative influences: Self-determination as a moderator of a normative feedback alcohol intervention. Health Psychology. 2006;25:571–579. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods. 2011;16:93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shean G, Baldwin G. Sensitivity and specificity of depression questionnaires in a college-age sample. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2008;169:281–288. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.169.3.281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB, Wills TA. Alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms: A multidimensional model of common and specific etiology. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:415–427. doi: 10.1037/a0016003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, Carey KB. The relationship between drinking control strategies and college student alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:338–345. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters GD. Behavioral self-control training for problem drinkers: A meta-analysis of randomized control studies. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:135–149. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(00)80008-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Field CA, Jouriles EN. Dismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0014472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Brown GS. Estimating variability in outcomes attributable to therapists: A naturalistic study of outcomes in managed care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:914–923. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Kraus CL, Swartzwelder HS. Many college freshmen drink at levels far beyond the binge threshold. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1006–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Morgan TJ, Pugh LA, Celinska K, Labouvie EW, Pandina RJ. Evaluating two brief substance-use interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:309–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]