Abstract

Purpose:

Tigatuzumab (TIG), an agonistic anti-DR5 monoclonal antibody, triggers apoptosis in DR5+ human tumor cells without crosslinking. TIG has strong in vitro/in vivo activity against basal-like breast cancer cells enhanced by chemotherapy agents. This study evaluates activity of TIG and chemotherapy in patients with metastatic triple negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Methods:

Randomized 2:1 phase II trial of albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-PAC) ± TIG in patients with TNBC stratified by prior chemotherapy. Patients received nab-PAC weekly x 3 ± TIG every other week, every 28 days. Primary objective was within-arm objective response rate (ORR). Secondary objectives were safety, progression free survival (PFS), clinical benefit, and TIG immunogenicity. Metastatic research biopsies were required.

Results:

Among 64 patients (60 treated; TIG/nab-PAC n=39 and nab-PAC n=21), there were 3 complete remissions (CRs), 8 partial remissions (PRs; 1 almost CR), 11 stable diseases (SDs) and 17 progressive diseases (PDs) in the TIG/nab-PAC arm (ORR=28%), and no CRs, 8 PRs, 4 SDs and 9 PDs in nab-PAC arm (ORR=38%). There was a numerical increase in CRs and several patients had prolonged PFS (1025+, 781, 672, 460, 334) in the TIG/nab-PAC arm. Grade 3 toxicities were 28% and 29% respectively with no grade 4–5. Exploratory analysis suggests an association of ROCK1 gene pathway activation with efficacy in the TIG/nab-PAC arm.

Conclusions:

ORR and PFS were similar in both. Preclinical activity of TIG in basal-like breast cancer and prolonged PFS in few patients in the combination arm support further investigation of anti-DR-5 agents. ROCK pathway activation merits further evaluation.

Keywords: Tigatuzumab, nab-PAC, Monoclonal, Antibody, Triple negative, Breast Cancer

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is defined by the absence of estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER/PR), and HER-2 amplification; further sub-classification is being evaluated1. TNBC represents 15 to 20% of all breast cancers2–5 and is more frequent in younger patients, BRCA1 mutation carriers, and in specific ethnic groups such as African American women.6, 7 TNBC tumors are generally invasive ductal carcinomas and often have unfavorable features such as higher histologic grade, larger tumor size, and positive lymph nodes.8 The metastatic potential in TNBC is similar to that of other subtypes, but these tumors are associated with a shorter median time to relapse and death.9, 10 TNBC represents a significant clinical challenge as there are no targeted drugs available; chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment, but important limitations still need to be overcome in the next few years if any significant clinical strides are to be made.

Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), a member of the TNF superfamily of cytokines, is a type 2 membrane protein expressed in the majority of normal tissues and can undergo protease cleavage, resulting in a soluble form able to bind to TRAIL death receptors (DRs).11 TRAIL induces apoptosis of cancer cells in vitro and has potent tumor activity against tumor xenografts of various cancers in vivo via DRs.11 Although five receptors for TRAIL have been identified, only two (DR4 and DR5) are able to trigger apoptosis of tumor cells through activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway (caspase mediated).11–14 High expression of DR5 is frequently observed in various human cancers including breast cancer.15–21

Tigatuzumab (TIG) is the humanized version of the agonistic anti-DR5 murine monoclonal antibody TRA-8.21–23 It is composed of the complementarity-determining region of the murine antibody and the variable region framework and constant regions of human immunoglobulin IgG-1 mAb58’CL.21 TIG is able to trigger apoptosis in DR5-positive human tumor cells without the aid of crosslinking. 21, 22 In preclinical studies, the antibody has demonstrated strong in vitro and in vivo activity against basal-like breast cancer cells that is enhanced by chemotherapy agents like paclitaxel and albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-PAC).22–25

A phase 1, dose-escalation study of TIG in patients with relapsed or refractory carcinomas was conducted to determine the maximal tolerated dose (MTD), pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and safety.26 Seventeen patients were enrolled in 4 cohorts (1, 2, 4 and 8 mg/kg). TIG was well tolerated with no infusion reactions or grade 3–4-5 toxicity; the MTD was not reached. Plasma half-life was 6–10 days, and no anti-TIG responses were detected. Seven patients had stable disease (SD), with the duration of response ranging from 81 to 798 days. Phase 2 studies in other solid tumors using TIG in combination with chemotherapy demonstrated the safety of the combination.27

Thus, based on the preclinical data and the safety of TIG as single agent and in combination with chemotherapy, we conducted a randomized, phase II clinical trial, of nab-PAC with or without TIG in patients with TNBC.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Patients older than 18 years of age with histologically confirmed metastatic TNBC were enrolled. A tumor was considered triple negative if HER-2-neu was negative (0 or 1+ staining by IHC or gene amplification ratio < 2.0 by FISH), and the ER and PR were negative ( <1% of the tumor cells by IHC). There was no restriction as to the number of prior chemotherapy regimens for metastatic disease but patients had to have prior exposure to anthracyclines and taxanes in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant settings. Patients with no prior chemotherapy for metastatic disease and patients who have received prior therapy with taxanes for metastatic disease (paclitaxel or docetaxel) were eligible. All patients had to have measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST Version 1.1), an ECOG ≤ to 2, and adequate organ and bone marrow function (Supplemental Material). Patients previously treated with nab-PAC or with active central nervous involvement were excluded.

Study Design and Treatment Schedule

This study was a randomized (2:1) phase 2 multicenter trial of nab-PAC with or without TIG in patients with metastatic TNBC. The trial was conducted through the Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium (TBCRC); 13 sites activated the study. A treatment cycle was defined as 4 weeks. Patients received intravenous nab-PAC on days 1, 8, and 15 (100 mg/m2) at 28-days interval with or without TIG intravenously on days 1 and 15 of every cycle (10 mg/kg loading dose followed by 5 mg/kg every other week). Response to therapy was assessed every two cycles (every 8 weeks). Treatment continued without interruption in patients with a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) or SD until progressive disease (PD) or unacceptable toxicity. Patients with tumor progression on the nab-PAC arm were allowed to rollover to the TIG/nab-PAC arm. All patients gave informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by local Institutional Review Boards and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonization Guideline E6 for Good Clinical Practice and applicable local regulatory requirements.

Study End Points

The primary efficacy end point was objective response rate (ORR) based on RECIST 1.1 criteria. Secondary efficacy end points were progression free survival (PFS), duration of response, clinical benefit ratio (CBR) and safety of the combination. The ORR was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved best overall response of confirmed CRs and PRs. PFS was defined as the time from the date of initial treatment to the date of the first objective documentation of PD or death. The duration of response was defined as the time from the date of the first documentation of CR or PR to the date of the first documentation of PD. CBR for this protocol was defined as the percentage of patients who have achieved CR, and PR and SD for > 4 cycles. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were collected and reported from the time of the first dose administration of the study drugs to 30 days after the last dose administration. Toxicities were graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse events (CTCAE) Version 3.0.

Human anti-human antibody measurements (HAHA) were conducted before the infusion of TIG, at 4 and 8 weeks after the TIG infusion and every 8 weeks thereafter during active treatment, and 3 months after the end of treatment. HAHA analysis was performed using a qualitative solid-phase assay as previously described.26

Biopsy of a reasonably accessible metastatic lesion (chest wall, breast, skin, subcutaneous, superficial lymph nodes, bones and liver metastases) was required for participation in the trial. Lung and brain metastasis were not considered reasonably accessible lesions. Biopsy samples were obtained using a 14–18 gauge core needle; at least two core biopsies were obtained and snap frozen individually and a third one for the preparation of paraffin-embedded blocks. Frozen tissues were used for high-throughput genomic analyses after macro-dissection and data related to treatment response is presented in this manuscript.

Tumor sample processing

De-identified fresh frozen tumor tissue biopsy specimens were obtained from the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Comprehensive Cancer Center Tissue Procurement Shared Facility. The specimens were macro-dissected by a board certified pathologist at the Tissue Procurement Shared Facility to enrich for tumor cell content and remove adjacent normal tissue. The dissected specimens were weighed, transferred to a 15 mL conical tube containing ceramic beads, and RLT Buffer (Qiagen) plus 1% BME was added so that the tube contained 35 uL of buffer for each milligram of tissue. The conical tubes containing tissue, ceramic beads and buffer were agitated in a MP Biomedicals FastPrep machine at 6.5 meters per second for 90 seconds to homogenize the tissue. The homogenized tissue was stored at −80°C. Total RNA was extracted from 350 uL of tissue homogenate (equivalent to 10 mg of tissue) using the Norgen Animal Tissue RNA Purification Kit (Norgen Biotek Corporation). Cell lysate was treated with Proteinase K before it was applied to the column and on-column DNAse treatment was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was eluted from the columns and quantified using the Qubit RNA Assay Kit and the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen). RNA-seq libraries for each sample were constructed from 250 ng total RNA using the polyA selection and transposase-based non-stranded library construction (Tn-RNA-seq) described previously.28 RNA-seq libraries were barcoded during PCR using Nextera barcoded primers according to the manufacturer (Epicentre). The RNA-seq libraries were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit and the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen) and four barcoded libraries were pooled in equimolar quantities for sequencing. The pooled libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing machine using paired-end 50 bp reads and a 6 bp index read, and we obtained at least 50 million read pairs from each library. TopHat v1.4.129 was used with the options -r 100 -mate-std-dev 75 to align 50 million RNA-seq read pairs, and used GENCODE version 930 as a transcript reference. Gene expression values (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million reads, FPKMs) were calculated for each GENCODE transcript using Cufflinks 1.3.0 with the -u option.31

Statistics

There were no prior data on ORR of nab-PAC in this patient population although a trial of nab-PAC in patients with therapy resistant tumors had a 14% ORR in the TNBC patient subgroup32. Patients were randomized in the trial as 2:1 ratio and stratified by patients’ prior chemotherapy. With an accrual of 40 patients to the TIG/nab-PAC regimen, the ORR estimation would have a standard error of less than 7.5% if one assumes the ORR is between 20%−35%; the estimated two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI) would be 21.2–51.7 for an ORR of 35% with Blythe-Still-Casella Exact Method and 9.4% - 34.4% if the ORR were 20%. In the single agent arm with 20 patients, the ORR would have a standard error of 8.9%; two-sided 95% CI would be 7.1% - 41.1% for an ORR of 20% using the same method. Descriptive analysis for patients demographic and clinical characteristics such as means, medians, and ranges were used to describe continuous variables. Frequency and proportion were used to describe categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine two portions in 2X2 contingency table. The K-M estimator was used to estimate median PFS. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals for the median survival time were constructed using a nonparametric method.33 Stratified log rank test was used to compare PFS curves.

A modified Gehan’s two-stage design was used in the trial34 to minimize exposure to ineffective therapy; at least one patient in the first 11 patients enrolled per arm had to have a CR or PR in order to complete enrollment in that arm. A safety interim analysis was scheduled to be done after the first 6 patients enrolled in the TIG/nab-PAC arm (Supplemental Material).

RNA-seq Gene Expression Analysis of Tumor Biopsy Tissue: DESeq235 was used to analyze gene count data to identify genes whose expression was significantly associated with response to therapy. The DESeq2 nbinomLRT function was used to identify genes that were significantly differentially expressed between two classes: Class 1 contained patients who achieved CR or PR, Class 2 contained patients who had SD or PD. We also identified genes that were significantly associated with response criteria when response was represented as a quantitative variable ranging from CR (1) to PR (2) to SD (3) to PD (4). The significant genes (FDR< 0.05) were filtered to identify genes whose maximum FPKM expression value across samples was greater than or equal to 1.

Results

Patients

Sixty-four patients were enrolled; 42 in the TIG/nab-PAC arm and 22 in the nab-PAC arm (Table 1). All patients gave signed informed consent, and 60 patients received at least 1 cycle of therapy. In the TIG/nab-PAC arm the median age for the patients was 51 years (range, 32 to 72), 33% were African American, 33% had no prior chemotherapy in the metastatic setting, and the median number of prior therapy regimens was 2 (range, 0–5). The nab-PAC arm had similar characteristics; in those patients the median age was 51 (range 34–75), 27% were African American, 32% had no prior chemotherapy in the metastatic setting, and the median number of prior chemotherapy regimens was 1 (range, 0 to 4). All patients had an ECOG of ≤ 2.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| TIG/nab-PAC (N=42) | nab-PAC (N=22) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 26 (63%) | 16 (73%) |

| Black | 14 (33%) | 6 (27%) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unknown |

1 (2%) |

0 (0%) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (min-max) |

51 (32–72) |

50.5 (34–75) |

| Prior treatment in metastatic setting | ||

| No prior Chemotherapy | 14 (33%) | 7 (32%) |

| Chemotherapy but no Taxane | 16 (39%) | 10 (45%) |

| Chemotherapy with a Taxane |

12 (28%) |

5 (23%) |

| Median # of Chemotherapy Regimens* | 2 (range, 0–5) | 1 (range, 0–4) |

Chemotherapy in the metastatic setting

Efficacy

Of the 42 patients in the TIG/nab-PAC arm, 39 received at least one course of therapy and were eligible for evaluation of response (3 patients had PD before initiation of therapy); of the 22 patients in the nab-PAC arm, 21 patients were treated and were eligible for evaluation of response (1 patient had PD before initiation of therapy). At least one PR was seen in the first 11 patients treated in each arm and accrual continued to completion. Eleven patients progressed before the first protocol-specified evaluation of response.

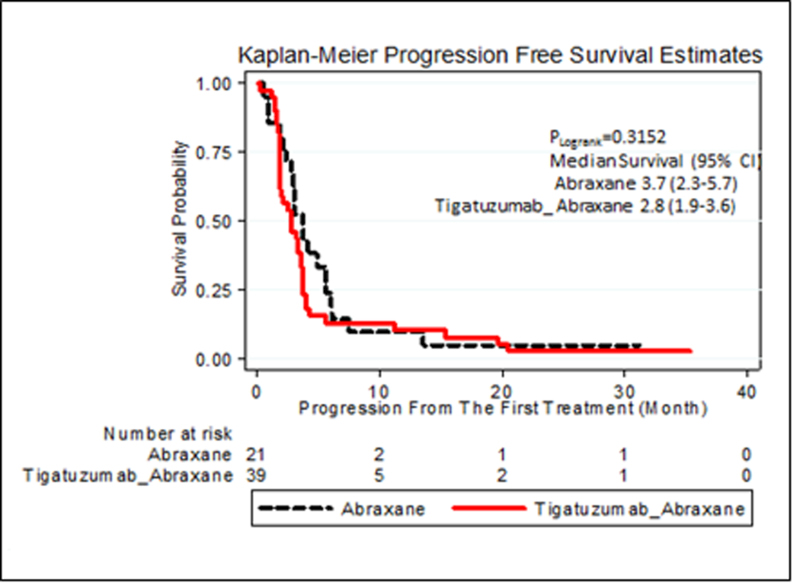

In the TIG/nab-PAC arm, there were 3 CRs, 8 PRs (1 patient had a near CR with 96% reduction in the index lesions) with an ORR of 28% (95% exact CI 14.9 to 45.0%). Their median PFS was 2.8 months (95% CI 1.9–3.6) (Table 2 and Figure 1A) and 3.8 months in patients with objective response (95% CI 2.8–19.7). Sixteen of the 39 patients (41%) in the TIG/nab-PAC arm achieved clinical benefit. The median PFS for patients enrolled in the TIG/nab-PAC arm was 2.8 months (95% CI 1.9–3.6). There were 5 patients in the TIG/nab-PAC arm with long PFS including 3 CR patients (1025+, 781, and 672 days), 1 near CR (460 days) and 1 SD (334 days). Four of the 11 patients that achieved CR or PR in the TIG/nab-PAC arm had progression in the brain but no systemic progression.

Table 2.

Efficacy Data

| Best Response | TIG/nab-PAC (n=39) | nab-PAC (n=21) |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Response | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Partial Response | 8 (21%) | 8 (38%) |

| Objective Response | 11 (28%) (95% CI 14.9–45%) | 8 (38%) (95% CI 18–61.1%) |

| Stable Disease | 11 (28%) | 4 (19%) |

| Clinical Benefit Rate (> 4 cycles) | 16 (41%) | 11 (52%) |

| Progressive Disease | 17 (44%) | 9 (43%) |

| Median Duration of response – Days (Range) | 118+ (84 to 1025+) | 167+ (91 to 1004+) |

| Median Progression Free Survival - months | 2.8 (95% CI 1.9–3.6) | 3.7 (95% CI 2.3–5.7) |

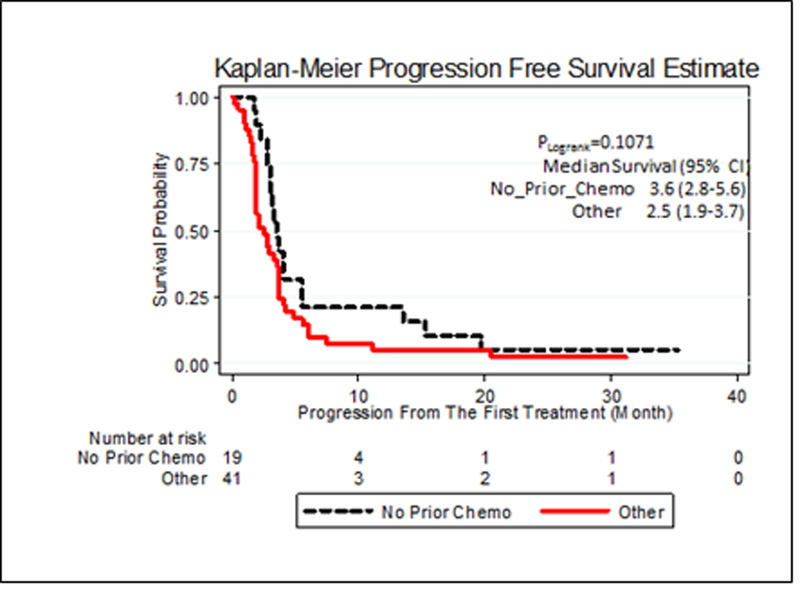

Figure 1.

A. Progression Free Survival for each arm of the trial

B. Progression Free Survival According to Prior Therapy for all Patients Enrolled in the Trial

Although the study was not designed for statistical comparison of the two treatment arms, the control arm (single agent nab-PAC) had similar overall efficacy as combination therapy with an ORR of 38% (95% CI exact 18–61.1%), no CRs and 8 PRs. Clinical benefit was noted in 11 patients (52%) enrolled in the nab-PAC arm (Table 2). The median PFS for patients enrolled in the nab-PAC arm was 3.7 months (95% CI 2.3–5.7) (Figure 1A), and long term PFS occurred in 1 patient (1004+ days). Two additional patients had PFS for 224 and 220 days. Thus, proportionally more patients in the combination arm experienced prolonged clinical benefit (5 out of 39 [13%] versus 1 out of 21 [5%] patients). No objective responders in the nab-PAC arm had progression in the brain without progression of index lesions.

Patient Demographics and Efficacy

We examined the effect of patient demographics and prior therapy on the whole patient population since outcomes were similar in the two arms (Table 3). Chemotherapy naïve patients had an increased ORR (53% [95% CI exact 31–76.3%] vs. 22% [95% CI exact 10.5–40.1%] respectively) and decreased PD rate (26 vs. 51% respectively). PFS was not significantly greater (3.6 vs. 2.5 months; Figure 1B) while the median duration of the response was 137 days (range, 84–1025+ days) and 174 days (range, 111–1004+ days) respectively. Among the 19 patients who were chemotherapy naïve in the metastatic setting, 53% had objective response, 68% had clinical benefit and PFS of 3.6 months (95% CI 2.8–5.6) compared with 22%, 34% and 2.5 months (95% CI 1.9–3.7) for those patients that received prior chemotherapy in the metastatic setting. We found no differences in efficacy for other factors including race (white vs. black), age (less than or greater than 50), tumor behavior (less than or greater than 2 years between primary tumor and relapse), or superficial extent (breast, soft tissue, lymph nodes) vs. systemic metastasis (liver, lung, bone).

Table 3.

Prior Therapy effect on Efficacy Data

| Chemo naïve (n=19) | Prior Chemo (n=41) | |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Response | 2 (11%) | 1 (2%) |

| Partial Response | 8 (38%) | 8 (28%) |

| Objective Response | 10 (53%)***(95% CI 31–76.3%) | 9 (22%)(95% CI 10.5–40.1%) |

| Stable Disease* | 4 (21%) | 11 (27%) |

| Clinical Benefit** | 13 (68%) | 14 (34%) |

| Progressive Disease | 5 (26%) | 21 (51%) |

| Median Duration of Response – Days (range) | 137+ (84 to1025+) | 174+ (111 to 1004+) |

| Median Progression Free Survival – months | 3.6 (95% CI 2.8–5.6) | 2.5 (95% CI 1.9–3.7) |

Initial evaluation at day 56 (2 cycles of therapy)

CR and PR and Stable disease greater than 4 cycles of therapy

p < 0.0347 (Fisher Exact Test)

Safety

Thirty nine patients in the TIG/nab-PAC arm and 21 in the nab-PAC arm received at least one cycle of therapy and were eligible for toxicity evaluation (Table 4). No adverse or serious adverse events (AEs/SAEs) related with the research agent were seen in the first 6 patients treated in the TIG/nab-PAC arm and accrual continued to completion.

Table 4.

Adverse Events Related with Protocol-Therapy

| Adverse Events Possible Related with Protocol Therapy Seen in More Than 10% of all Patients (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIG / nab-PAC (39) |

nab-PAC(n=21) |

||||||

| Toxicity Grade | Toxicity Grade | ||||||

| All Patients |

1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Fatigue | 33 (54) | 14 (36) | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | 6 (29) | 3 (14) | 2 (10) |

| Alopecia | 30 (49) | 11(28) | 8 (21) | - | 7 (33) | 4 (19) | - |

| Peripheral Sensory Neuropathy | 27 (44) | 13 (33) | 4 (10) | 0 | 8 (38) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Anemia | 25 (41) | 8 (21) | 7 (18) | 1 (3) | 4 (19) | 5 (24) | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 23 (38) | 5 (13) | 4 (10) | 6 (15) | 2 (10) | 3 (14) | 3 (14) |

| Nausea | 14 (23) | 6 (15) | 3 (8) | 0 | 2 (10) | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (10) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 6 (10) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (5) | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 6 (10) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Vomit | 6 (10) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (10) | 0 |

Therapy in both arms was well tolerated; the majority of the AEs were grade 1–2 with very few grade 3 events and no grade 4/5 toxicity. There were no AEs or SAEs associated with TIG infusions. The most common AEs observed in at least 10% of all patients enrolled in the trial deemed by the investigators to be possibly related with the protocol therapy were fatigue (54%), alopecia (49%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (44%), anemia (41%), neutropenia (38%), nausea (23%), thrombocytopenia (10%), anorexia (10%), diarrhea (10%), and vomiting (10%). As expected, due to the use of nab-PAC, the most frequent grade 3 AEs were neutropenia (15%), fatigue (10%), anemia (2%) and peripheral sensory neuropathy (2%). The addition of TIG did not change the safety profile nab-PAC. The most frequent AE seen in the TIG/nab-PAC arm, excluding alopecia, was fatigue while the most frequently seen in the nab-PAC arm was peripheral sensory neuropathy.

Forty two SAEs were reported; 4 were classified as possibly related with the protocol therapy and 38 associated with PD. The 2 SAEs related in the TIG/nab-PAC arm were fever/neutropenia G4 and empyema/neutropenia G3; the 2 SAEs related in the nab-PAC arm were fever/neutropenia G2 and pulmonary thromboembolism. No deaths associated with the treatment agents were seen in the trial. None of the patients enrolled in the TIG/nab-PAC arm developed HAHA.

Biopsies

A successful biopsy was defined as one in which a patient had successful dual biopsies of any metastatic lesion (snap frozen), adequate tumor on macro-dissection to assure > 50% tumor cell nuclei and adequate DNA/RNA yield from the macro-dissected tissue. Of the 64 patients enrolled, 38 (59%) were successfully biopsied, 31 (48%) were judged adequate by macro-dissection and 28 (44%) had appropriate DNA/RNA yield for the study. Of the 28 samples, two were from patients who had PD prior to therapy, 20 received combination therapy (5 patients with CR/PR and 8 patients with PD) and 6 received single agent nab-PAC (3 patients with PR and 3 with PD). Seventeen of the 28 patients had only a single tissue sample adequate for DNA/RNA analysis while 11/28 had multiple adequate DNA/RNA samples. The most common biopsy sites for tissue inadequacy were nodes and soft tissue. The reason for tissue macro-dissection failure was extensive necrosis in 50% and absence of tumor cells (benign tissue) in 50% of the specimens. This 40% yield of tissue analysis in treated patients limits the genomic analysis but the 28 metastatic tissues will be extremely valuable in studies relevant to metastatic TNBC.

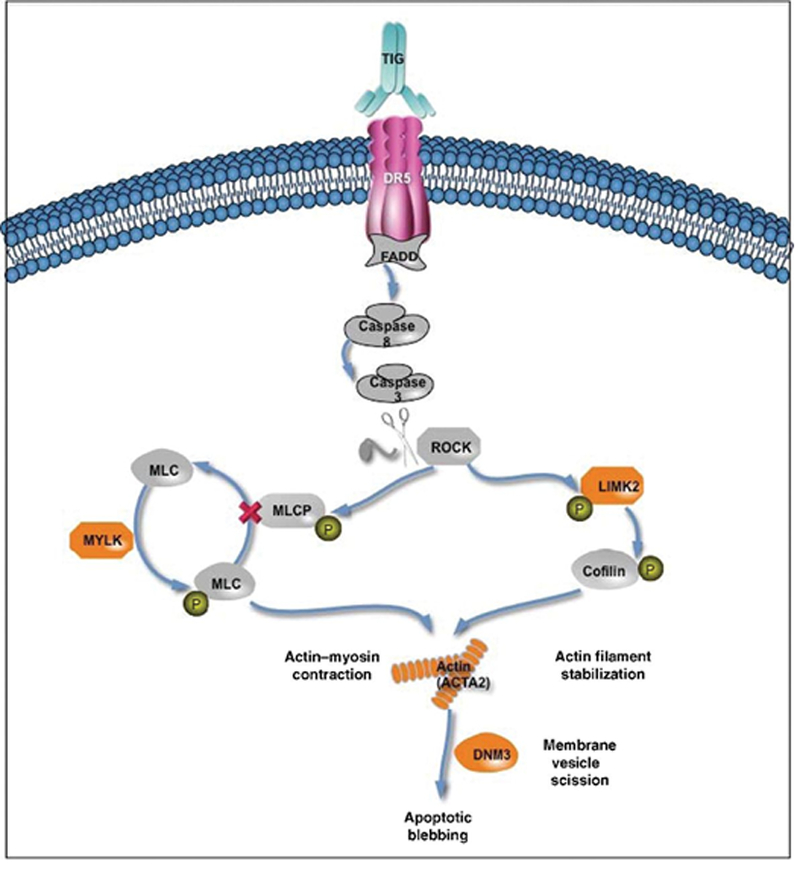

RNA-seq28 was used to measure gene expression in the tumors. Each tumor was classified as belonging to one of the six Vanderbilt TNBC subtypes;36, 37 There was no significant association between subtypes and response to therapy. Expression of all genes was examined and seven were significantly associated with response in the patients enrolled in the TIG/nab-PAC (False Discovery Rate < 0.05): ACTA2, DNM3, FBXO32, IFFO2, LIMK2, MYLK, and ZNF469. All seven genes were expressed at a higher level in tumors from patients who responded to the combination therapy compared to those who did not. Several of these genes are involved in apoptotic membrane blebbing through DR5/Casp-3/ROCK1 signaling (Figure 2). Activation of DR5 leads to activation of Caspase-3, which cleaves and activates ROCK1. ROCK1 phosphorylates and inhibits MLCP leading to unopposed MYLK phosphorylation of MLC, which catalyzes the generation of actin-myosin contractile force that causes blebbing.38 ROCK1 also phosphorylates and activates LIMK2 which leads to the accumulation and stabilization of actin filaments, such as those composed of ACTA2, involved in constriction of the cytoskeleton and apoptotic membrane blebbing.39, 40 DNM3 is a member of the dynamin family that interacts with actin membrane processes and is responsible for constricting and releasing membrane vesicles. Thus, four of the seven genes significantly associated with response to TIG/nab-PAC are associated with the membrane blebbing process. This enrichment suggests that higher expression of this apoptotic pathway could be related to sensitivity to one or both of these drugs. Although the number of cases in the nab-PAC arm were very limited (6 patients), the expression of these seven genes was examined in tumors from those patients; these genes were not positively correlated with response to nab-PAC.

Figure 2.

Apoptotic membrane blebbing through DR5/Casp-3/ROCK1 signaling pathway. Genes associated with response to treatment with nab-PAC and TIG are highlighted in orange.

Discussion

This trial was undertaken based on the pre-clinical studies which indicated that basal like breast cancer cells were highly sensitive to anti-DR522−25, that the combination of an anti-DR5 monoclonal antibody and chemotherapy were quite effective in murine models of basal type breast cancer in vivo24 and that basal type breast tumor stem cells were killed by anti-DR5.25 Similar studies in hormone dependent and HER2 positive breast cancer demonstrated resistance to anti-DR5 therapy.22–25

At the time of this protocol design, it was not feasible to use platinum compounds as the chemotherapy backbone of our study in view of the expanded access program that was available then for the combination of carboplatin, gemcitabine and iniparib for patients with newly diagnosed metastatic TNBC following a promising phase 2 randomized trial of chemotherapy with/without iniparib.41 In addition, there was no prior prospective experience with nab-PAC in this patient population although heavily pretreated TNBC patients appeared to have a 14% response rate in retrospective analysis of nab-PAC as single agent in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Thus, we designed a randomized Phase 2 to obtain a reasonable measure of efficacy with the combination arm (objective response rate in 40 patients with a standard error < 7.5%). In addition, we included a single agent nab-PAC arm as a frame of reference for this patient population.

The outcome of the trial was that the combination arm had an ORR of 28% and PFS of 2.8 months. The experience was similar in the concurrent single arm with ORR of 38% and PFS of 3.7 months. This experience did not support moving forward with this current combination regimen in the same population of patients. Despite the negative overall trial findings, we did note that the combination arm included 3 CRs and 1 near CR while no CRs occurred in the single agent arm. In addition, proportionally more patients in the combination arm experienced prolonged clinical benefit (5 out of 39 [13%] versus 1 out of 21 [5%] patients). nab-PAC was associated with an unexpectedly high rate of objective response in patients with TNBC, reinforcing the need for a reference arm in our trial design; unfortunately, as with other agents evaluated in this patient population, responses were often no durable. A new anti-DR5 monoclonal antibody (DS8273 from Daiichi Sankyo) has shown better preclinical activity than TIG as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy and is now being evaluated in a phase 1 trial (NCT02076451).

Metastatic TNBC is an aggressive disease as illustrated in our trial with 4 enrolled patients having progression prior to initiation of therapy and 26/60 (43%) of treated patients had progression prior to or at their initial evaluation (8 weeks). Patients with no prior therapy for metastatic disease experienced a higher ORR and clinical benefit rate.

Our experience with core needle biopsies for genomic studies is informative in designing future correlative studies within trials. First, trials should be designed for patients with accessible metastases and biopsies should be required (100% biopsies). Second, duplicate biopsies would increase the yield of appropriate tissue samples and third, incisional biopsies on superficial metastatic sites (chest wall, breast and lymphatic nodes) should be considered.

Finally, our genomic analysis (RNA seq) relating to therapeutic response was limited due to small numbers of patients tissues with 20 samples in the combination therapy arm and 6 samples in the single agent nab-PAC arm. In the combination arm, efficacy was significantly associated with elevated levels of seven genes including 4 of which participate in DR5 mediated ROCK1 activation of apoptosis associated membrane blebbing. This is an important and interesting observation; interpretation is tempered by limited patient samples.

In conclusion, the high degree of anti-DR5 sensitivity of basal-like breast cancer cell lines compared to other tumor cell lines and the prolonged PFS in a few patients in the TIG/nab-PAC suggest that DR5-mediated therapy deserves further investigation with novel anti-DR5 agents.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

The DR-5 tumor cell receptor is a promising target for an antibody-based therapy as it is expressed in solid tumors including breast cancer. Activation of DR-5 triggers apoptosis of tumor cells through activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Tigatuzumab is a novel agonistic humanized monoclonal antibody against DR5. In preclinical studies the antibody demonstrated strong in vitro (cell lines) and in vivo (xenograft models) activity against basal-like breast cancer that is enhanced by chemotherapy agents including albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-PAC). Other types of breast cancer (hormone receptor and HER2 positive cancers) were resistant to Tigatuzumab alone or in combination with chemotherapy. Consequently, a clinical trial with this antibody in combination with nab-PAC in patients with triple negative breast cancer was conducted with signs of efficacy in a subset of patients. A single arm with nab-PAC was included as there was no prior prospective experience with this agent in this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by the Susan G Komen for the Cure Promise Grant (KG090969), the University of Alabama at Birmingham Breast Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence Award # NCI P50CA089019 from the National Cancer Institute, Daiichi Sankyo and Celgene. The Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium is supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the Avon Foundation, and Susan G. Komen for the Cure.

A.F.T. received support from Daiichi Sankyo and Celgene to conduct clinical and laboratory research (paid to the University of Alabama at Birmingham).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Presentation / Publications: Data from this work have been partially reported at the ASCO Annual Meeting in 2011 and 2013 (Abstract # TPS 128 and 1052 respectively).

Conflict of interest: The following authors have the following conflict of interest to disclose: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX. The remaining authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Mayer IA, Abramson VG, Lehmann BD, Pietenpol JA: New strategies for triple-negative breast cancer—deciphering the heterogeneity. Clin Cancer Res 2014, 20: 782–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D: Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2000, 406: 747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL: Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98: 10869–10874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Genome Atlas Network: Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumors. Nature 2012, 490: 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montagna E, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, Cancello G, Iorfida M, Balduzzi A, Galimberti V, Veronesi P, Luini A, Pruneri G, Bottiglieri L, Mastropasqua MG, Goldhirsch A, Viale G, Colleoni M: Heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer: histologic subtyping to inform the outcome. Clin Breast Cancer 2013, 13: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, Parise CA, Caggiano V: Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California cancer Registry. Cancer 2007, 109: 1721–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS: Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2010, 363: 1938–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dent R, Maureen T, Kathleen IP, Wedad MH, Harriet KK, Carol AS, Lavina AL, Ellen R, Ping S, Narod SA: Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res 2007, 13: 4429–4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blows FM, Driver KE, Schmidt MK, Broeks A, van Leeuwen FE, Wesseling J, et al. : Subtyping of breast cancer by immunohistochemistry to investigate a relationship between subtype and short and long term survival: a collaborative analysis of data for 10,159 cases from 12 studies. PLoS Med 2010, 7:e1000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langerod A, Zhao H, Borgan O, Nesland JM, Bukholm IR, Ikdahl T, Karesen R, Borresen-Dale AL, Jeffrey SS: TP53 mutation status and gene expression profiles are powerful prognostic markers of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2007, 9: 192–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashkenazi A: Directing cancer cells to self-destruct with pro-apoptotic receptor agonists. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008, 12: 1001–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debatin KM, and Krammer PH: Death receptors in chemotherapy and cancer. Oncogene 2004, 16: 2950–2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debatin KM: Apoptosis pathways in cancer and cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2004, 3: 153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiezorek J, Holland P, and Graves J: Death receptor agonists as a targeted therapy for cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010, 6: 1701–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koornstra JJ, Jalving M, Rijcken FE, Westra J, Zwart N, Hollema H, et al. : Expression of tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand death receptors in sporadic and hereditary colorectal tumours: potential targets for apoptosis induction. Eur J Cancer 2005, 8: 1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perraud A, Akil H, Nouaille M, Petit D, Labrousse F, Jauberteau MO, et al. : Expression of p53 and DR5 in normal and malignant tissues of colorectal cancer: correlation with advanced stages. Oncol Res 2011. 5: 1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen XP, He SQ, Wang HP, Zhao YZ, and Zhang WG: Expression of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptors and antitumor tumor effects of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in human hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2003, 11: 2433–2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong HP, Kleinberg L, Silins I, Florenes VA, Trope CG, Risberg B, et al. : Death receptor expression is associated with poor response to chemotherapy and shorter survival in metastatic ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 2008, 1: 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spierings DC, de Vries EG, Timens W, Groen HJ, Boezen HM, and de Jong S: Expression of TRAIL and TRAIL death receptors in stage III non-small cell lung cancer tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2003, 9:3397–3405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hesry V, Piquet-Pellorce C, Travert M, Donaghy L, Jegou B, Patard JJ, et al. : Sensitivity of prostate cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis increases with tumor progression: DR5 and caspase 8 are key players. Prostate 2006, 9: 987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yada A, Yazawa M, Ishida S, Yoshida H, Ichikawa K, Kurakata S, et al. : A novel humanized anti-human death receptor 5 antibody CS-1008 induces apoptosis in tumor cells without toxicity in hepatocytes. Ann Oncol 2008, 6: 1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichikawa K, Liu W, Zhao L, Wang Z, Liu D, Ohtsuka T, et al. : Tumoricidal activity of a novel anti-human DR5 monoclonal antibody without hepatocyte cytotoxicity. Nat Med 2001, 8: 954–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchsbaum DJ, Zhou T, Grizzle WE, Oliver PG, Hammond CJ, Zhang S, Carpenter M, LoBuglio AF. Antitumor efficacy of TRA-8 anti-DR5 monoclonal antibody alone or in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy in a human breast cancer model. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 3731–3741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliver PG, LoBuglio AF, Zhou T, Forero A, Kim H, Zinn KR, Zhai G, Li Y, Lee CH, Buchsbaum DJ: Effect of anti-DR5 and chemotherapy on basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; 133(2):417–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Londoño-Joshi AI, Oliver PG, Li Y, Lee CH, Forero-Torres A, LoBuglio AF, Buchsbaum DJ. Basal-like breast cancer stem cells are sensitive to anti-DR5 mediated cytotoxicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; 133(2):437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forero-Torres A, Shah J, Wood T, Posey J, Carlisle R, Copigneaux C, et al. : Phase I trial of weekly tigatuzumab, an agonistic humanized monoclonal antibody targeting death receptor 5 (DR5). Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2010, 1: 13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forero-Torres A, Infante JR, Waterhouse D, Wong L, Vickers S, Arrowsmith E, He R, Hart L, Trent D, Wade J, Jin X, Wang Q, Austin T, Rosen M, Beckman R, von Roemelng R, Greenberg J, Saleh M. Phase 2, multicenter, open-label study of tigatuzumab (CS-1008), a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting death receptor 5, in combination with gemcitabine in chemotherapy-naive patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Medicine 2013, 2(6): 925–32. Epub 2013 Oct 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gertz J, Varley KE, Davis NS, Baas BJ, Goryshin IY, Vaidyanathan R, Kuersten S, Myers RM. Transposase mediated construction of RNA-seq libraries. Genome Res 2012, 22(1): 134–41. Epub 2011 Nov 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 2009, 25(9):1105–11. Epub 2009 Mar 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrow J, Denoeud F, Frankish A, Reymond A, Chen CK, Chrast J, Lagarde J, Gilbert JG, Storey R, Swarbreck D, Rossier C, Ucla C, Hubbard T, Antonarakis SE, Guigo R. GENCODE: producing a reference annotation for ENCODE. Genome Biol 2006, 7 Suppl 1:S4.1–9. Epub 2006 Aug 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28 (5):511–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gradishar WJ, Krasnojon D, Cheporov S, Makhson AN, Manikhas GM, Clawson A, Bhar P. Significantly longer progression-free survival with nab-paclitaxel compared with docetaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(22): 3611–3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brookmeyer R, and Crowley J A Confidence Interval for the Median Survival Time. Biometrics 1982; 38, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gehan EA. The determination of the number of patients required in a preliminary and a follow-up trial of a new chemotherapeutic agent. J Chronic Dis 1961; 13: 346.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology 2010, 11 (10): R106 Epub 2010 Oct 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X, Li J, Gray WH, Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Shyr Y, Pietenpol JA. TNBC type: A subtyping tool for triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Inform 2012; 11: 147–56. Epub 2012 Jul 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, Pietenpol JA.Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Invest 2011, 121(7):2750–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sebbagh M, Renvoizé C, Hamelin J, Riché N, Bertoglio J, Bréard J. Caspase-3-mediated cleavage of ROCK I induces MLC phosphorylation and apoptotic membrane blebbing. Nat Cell Biol 2001, 3(4):346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amano T, Tanabe K, Eto T, Narumiya S, Mizuno K. LIM-kinase 2 induces formation of stress fibres, focal adhesions and membrane blebs, dependent on its activation by Rho-associated kinase-catalysed phosphorylation at threonine-505. Biochem J 2001, 15 (354):149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coleman ML, Sahai EA, Yeo M, Bosch M, Dewar A, Olson MF. Membrane blebbing during apoptosis results from caspase-mediated activation of ROCK I. Nat Cell Biol 2001, 3(4): 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Shaughnessy J, Osborne C, Pippen JE, et al. Iniparib plus chemotherapy in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.