Abstract

Mitochondria play key roles in mammalian apoptosis, a highly regulated genetic program of cell suicide. Multiple apoptotic signals culminate in mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), which not only couples the mitochondria to the activation of caspases but also initiates caspase-independent mitochondrial dysfunction. The BCL-2 family proteins are central regulators of MOMP. Multidomain pro-apoptotic BAX and BAK are essential effectors responsible for MOMP, whereas anti-apoptotic BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 preserve mitochondrial integrity. The third BCL-2 subfamily of proteins, BH3-only molecules, promotes apoptosis by either activating BAX and BAK or inactivating BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1. Through an interconnected hierarchical network of interactions, the BCL-2 family proteins integrate developmental and environmental cues to dictate the survival versus death decision of cells by regulating the integrity of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Over the past 30 years, research on the BCL-2-regulated apoptotic pathway has not only revealed its importance in both normal physiological and disease processes, but has also resulted in the first anti-cancer drug targeting protein-protein interactions.

Introduction

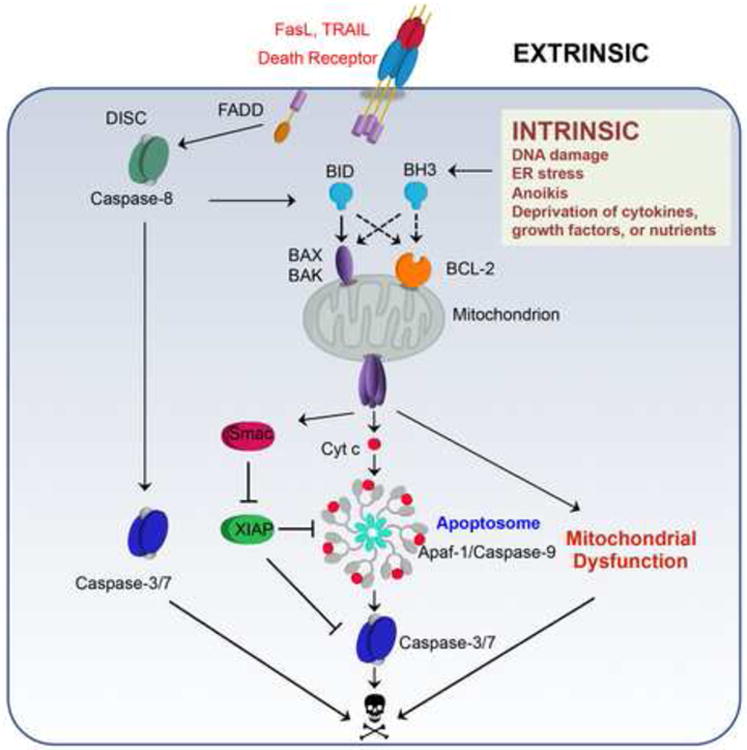

Apoptosis is the best-studied form of programmed cell death, which is indispensable for the development and maintenance of homeostasis within multicellular organisms [1]. Dysregulation of apoptosis incurs a wide variety of human illness ranging from neurodegenerative disorders to cancer [1]. Apoptosis can be initiated through either intrinsic or extrinsic pathways, both of which activate caspases that are executioners of apoptosis; processing of cellular substrates by these enzymes leads to the characteristic morphological and biochemical features of apoptosis [1]. The intrinsic pathway is activated by a wide variety of cellular stresses including DNA damage, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and deprivation of cytokines, growth factors, or nutrients, whereas the extrinsic pathway is initiated by the engagement of cell surface “death receptors” such as FAS and TRAIL receptors (Fig. 1). The intrinsic death signals culminate in MOMP, resulting in the release of apoptogenic factors including cytochrome c and SMAC [2]. Upon binding to cytochrome c and dATP, APAF-1 oligomerizes into a heptameric complex known as the apoptosome, which recruits and activates caspases [3]. Death receptor engagement can lead to initiator caspase-8 and subsequent effector caspase-3/7 activation in so-called ‘type I’ cells, such as T-lymphocytes. However, in ‘type II’ cells, such as hepatocytes, effector caspase activation requires a mitochondrial amplification loop to alleviate XIAP-mediated caspase inhibition through mitochondrial release of SMAC (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of apoptosis.

The intrinsic pathway is initiated by death stimuli including DNA damage, ER stress, anoikis, and deprivation of cytokines, growth factors or nutrients, resulting in transcriptional or post-translational activation of BH3-only molecules (BH3s). Activator BH3s, including BID, BIM, PUMA, and NOXA, directly activate BAX and BAK to induce the homo-oligomerization of BAX and BAK, leading to mitochondrial outer member premeabilization (MOMP) and release of cytochrome c and SMAC from the mitochondrial intermembrane space to the cytosol. Upon binding to cytochrome c and dATP, APAF-1 oligomerizes into a heptameric complex known as the apoptosome, resulting in the recruitment and activation of caspase-9 and subsequent activation of effector caspase-3/7. The extrinsic pathway of apoptosis is initiated by engagement of cell surface death receptors, such as FAS or TRAIL receptors, resulting in the recruitment of adaptor proteins such as FAS-associated death domain (FADD). FADD then dimerizes with procaspase-8 to form the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) and promote the auto-activation of procaspase-8. In ‘type I’ cells with low expression of the caspase inhibitor XIAP, such as T-lymphocytes, death receptor mediated caspase-8 activation is sufficient to activate effector caspase-3/-7. In ‘type II’ cells with high expression of XIAP, such as hepatocytes, effector caspase activation requires a mitochondrial amplification loop to alleviate XIAP-mediated caspase inhibition through mitochondrial release of SMAC. Caspase-8 mediated proteolytic cleavage of cytosolic BID into truncated BID (tBID) activates BAX and BAK-dependent MOMP, connecting the extrinsic pathway to the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

The BCL-2 family proteins are central regulators of MOMP [1]. The founding member BCL-2 was cloned from the t(14;18)(q32;q21) breakpoint, pathognomonic of human follicular lymphoma. The discovery that BCL-2 promotes cellular survival rather than proliferation initiated a new category of oncogenes [4]. Over the years, at least 15 members of the BCL-2 family have been identified that either prevent or promote apoptosis. They are now divided into three subfamilies: (1) multidomain anti-apoptotic BCL-2, BCL-XL (BCL2L1), MCL-1, BCL-W (BCL2L2), and A1 (BCL2A1); (2) multidomain pro-apoptotic BAX and BAK; and (3) pro-apoptotic BH3-only molecules (BH3s). Multidomain members share sequence homology with all four conserved BCL-2 homology domains (BH1-4), whereas BH3s only contain the BH3 domain. Most BCL-2 family members also harbor a C-terminal transmembrane anchor that targets these proteins to the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM). Although BOK shares significant sequence homology with BAX and BAK, it neither rescues the apoptotic defects of Bax-/-Bak-/- double knockout (DKO) cells nor is regulated by other BCL-2 members, and is considered as a non-canonical BCL-2 member [5].

Since the discovery of BAX and BAK, it was known that anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic BCL-2 members form heterodimers [1]. This led to a major debate in 1990s regarding whether multidomain anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic BCL-2 members are downstream effectors in controlling apoptosis. The generation of Bax-/-Bak-/- DKO mice provided convincing evidence that BAX and BAK are the essential downstream effectors of mitochondrial apoptosis [6-8]. However, BAX and BAK are kept inactive in viable cells and need to be activated upon death signaling to trigger MOMP. Hence, the next major debate was how BAX and BAK are activated and whether the “activator” subgroup of BH3s are required for their activation. The generation of Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- quadruple knockout (QKO) mice deficient for all activator BH3s provided in vivo evidence supporting direct activation of BAX and BAK by BID, BIM, PUMA, and NOXA. It also concurrently revealed that BH3-independent autoactivation of BAX and BAK can occur when BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 are simultaneously downregulated, but with slower kinetics compared to BH3-mediated activation [9]. Here, we summarize recent advances in how the BAX and BAK-dependent mitochondrion-dependent cell death program is regulated.

BH3s relay death signals to multidomain BCL-2 members to initiate mitochondrial apoptosis

BH3s are sentinels for cellular stress and function as initiator cell death signaling molecules with each BH3 coupled to a specific death signal. Their activity is regulated transcriptionally or by post-translational modifications. For example, genotoxic stress activates p53 to induce PUMA and NOXA, while cytokine/growth factor deprivation triggers nuclear translocation of FOXO1/3 to transactivate PUMA or BIM in a cell type-specific manner [1,10]. ER stress activates BIM through CHOP-mediated transcription as well as protein phosphatase 2A-mediated dephosphorylation [11]. In contrast, phosphorylation of BIM by the kinases ERK and RSK targets BIM for β-TRCP-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-dependent degradation [12]. Death receptor ligation results in caspase-8 mediated proteolytic cleavage of cytosolic BID into truncated BID (tBID), which then targets to the mitochondria to activate BAX and BAK, connecting the extrinsic pathway to the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathway [1]. BH3s interconnect signal transduction and multidomain BCL-2 family checkpoints by either activating BAX/BAK or inactivating anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members through direct binding [13,14]. Accordingly, BH3s have been divided into two classes, “activator” and “inactivator” (or “sensitizer”) [13,14].

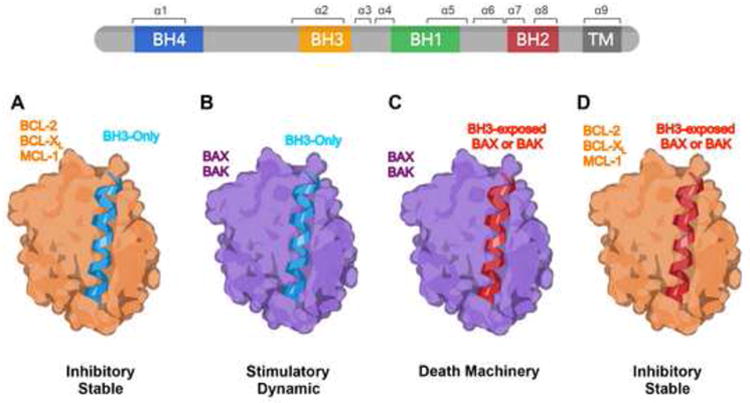

BH3-in-Groove: a structural basis of heterodimerization between BCL-2 members and homodimerization of BAX or BAK

The BCL-2 family proteins regulate mitochondrial apoptosis through protein-protein interactions, all involving the same BH3 helix-in-groove structure [15] (Fig. 2). The BH1, BH2, and BH3 domains of multidomain anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic members can form a hydrophobic binding groove (or canonical dimerization groove) that accommodates the amphipathic alpha-helical BH3 domain in BH3s. The interaction between activator BH3s and multidomain BAX or BAK has been debated for decades due to low binding affinity. Recent biophysical demonstration of BID, BIM or PUMA bound to BAX or BAK by NMR or crystal structures have helped resolve this controversy [16-20]. The binding of BH3s to multidomain anti-apoptotic members is inhibitory and stable (Fig. 2A), whereas the binding of activator BH3s to BAX/BAK is stimulatory and dynamic (Fig. 2B). The major purpose of the latter interaction is to induce the exposure of the BH3 domain in BAX or BAK such that the “BH3-exposed” BAX or BAK monomer can bind to the hydrophobic dimerization groove of another BAX or BAK molecule, forming symmetric homo-dimers and subsequent homo-oligomers (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, the interaction between activator BH3 and BAX or BAK must be “hit-and-run”, consistent with the low binding affinity between activator BH3s and BAX or BAK. In contrast, BH3s bind tightly to anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members. By analogy, activator BH3s are death ligands, BAX/BAK are death receptors, and the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members function like “decoy” death receptors that form inert stable complexes with BH3s but are unable to assemble the homo-oligomerized death machinery. Notably, the BH3 domain of most BAX or BAK present in viable cells is not exposed [9,15,16,20-23]. Only partially activated BAX or BAK will expose the BH3 domain and as a result can bind to anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. BH3-in-groove: a structural basis of BCL-2 family interactions that control survival or death decisions.

A schematic depicts conceptual modeling of the different interactions among the BCL-2 family proteins. The BCL-2 family proteins regulate mitochondrial apoptosis through protein-protein interactions, all involving the same BH3 helix-in-groove structure. Multidomain BCL-2 family members have four BCL-2 homology (BH) domains and a C-terminus hydrophobic transmembrane domain (α9 helix). The BH1, BH2, and BH3 domains of multidomain anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic members form a hydrophobic binding groove (or canonical dimerization groove) that accommodates the amphipathic alpha helical BH3 domain of BH3-only molecules as well as the BH3 domains of “BH3-exposed” BAX or BAK. The binding of BH3s to multidomain anti-apoptotic members is inhibitory and stable (A), whereas the binding of activator BH3s to BAX/BAK is stimulatory and dynamic (B). The BH3-in-groove interaction also forms the structural basis for the formation of symmetric BAX or BAK homo-dimers (C), the minimal unit for the assembly of higher-order homo-oligomers that permeabilize the mitochondrial outer membrane. The BH3 domain of most BAX or BAK present in viable cells is not exposed. Only partially activated BAX or BAK will expose the BH3 domain and as a result can bind to anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members (D).

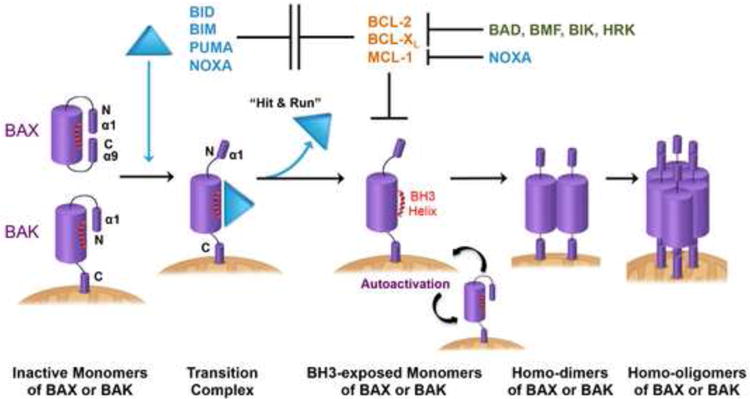

Direct activation of BAX and BAK by activator BH3s

Among BH3s, BID, BIM, PUMA, and NOXA are “activator BH3s” that directly interact with and induce the stepwise structural reorganization of BAX and BAK [7-9,13,18,24-26] (Fig. 3). Notably, only the BH3 peptides derived from BID and BIM, but not PUMA and NOXA, can consistently recapitulate the full-length proteins in activating BAX and BAK [27-29]. Hence, early classification of BH3s based on the activity of BH3 peptides has inherent limitations. In viable cells, BAX exists in the cytosol as a monomer with its α1 helix keeping the C-terminal α9 helix engaged in the dimerization groove [21,24]. This auto-inhibited BAX monomer may be further stabilized by forming an asymmetric dimer with the α9 helix of one BAX molecule binding to the α1/α6 trigger site of the other BAX [30]. In contrast, BAK is constitutively inserted in the MOM via its C-terminal α9 helix and maintained as an inactive monomer by VDAC2 [31]. Activation of BAX involves two distinct steps, mitochondrial targeting and homo-oligomerization, whereas that of BAK only involves the latter (Fig. 3). To induce mitochondrial targeting of BAX, the activator BH3s bind to the α1 helix or the α1/α6 trigger site of BAX, resulting in the exposure of the α1 helix and secondary disengagement of the α9 helix that inserts into the MOM [24,32,33]. Activator BH3s remain associated with the N-terminally exposed BAX through the canonical dimerization groove to drive the exposure of the BH3 domain and ensuing homo-dimerization of BAX [16,18,24]. Binding of activator BH3s to the canonical dimerization groove of BAK also induces the exposure of the α1 helix and the BH3 domain [9,17,19,20,22,34]. X-ray crystallography has shown the unfolding of BAX or BAK into an N-terminal ‘core’ (α2–α5) and a C-terminal ‘latch’ (α6–α8) upon activation by BH3 peptides [15,16,20], which may help eject activator BH3s. Whether this occurs in the MOM remains to be determined. The symmetric homo-dimers of BAX or BAK further assemble into homo-oligomers through either the α6/α6 or α3/α5 interface [35,36]. Deciphering how the homo-oligomers of BAX or BAK permeabilize the MOM is currently an area of intense investigation. BAX or BAK homo-oligomers have been proposed to form either proteinaceous or lipidic pores in the MOM [37-39], and visualization of the BAX oligomers in the MOM recently became feasible through super-resolution imaging [40,41].

Figure 3. Interconnected hierarchical regulation of BAX- and BAK-dependent mitochondrial apoptosis.

Activator BH3s, including BID, BIM, PUMA, and NOXA, directly interact with BAX and BAK to induce the stepwise structural reorganization of BAX and BAK. In viable cells, BAX exists as a cytosolic monomer with its α1 helix keeping the C-terminal α9 helix engaged in the dimerization groove, while BAK is constitutively inserted in the MOM via its C-terminal α9 helix. The binding of activator BH3s drives the dissociation of an N-terminal α1 helix of BAX or BAK and mobilizes the C-terminal α9 of BAX for translocation to the MOM. Activator BH3s remain associated with the N-terminally exposed BAX or BAK through the canonical dimerization groove to drive the exposure of the BH3 domain. Partially activated, BH3-exposed BAX or BAK monomers then can bind to the hydrophobic dimerization groove of another BAX or BAK molecule to initiate homo-dimerization and subsequent homo-oligomerization. The interaction between activator BH3s and BAX or BAK is “hit-and-run” because the same binding interface of BAX and BAK is used for homo-dimerization. Anti-apoptotic BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 sequester activator BH3s to prevent the initiation of BAX and BAK activation, providing frontline protection. As the second line of defense, anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members can also sequester “BH3-exposed” BAX and BAK monomers to prevent the homo-oligomerization of BAX and BAK. Autoactivation of BAX and BAK can occur independently of activator BH3s when BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 are simultaneously downregulated, albeit with slower kinetics compared to BH3-mediated activation. BH3-exposed BAX or BAK monomers can serve as activators of BAX and BAK to induce a “feed-forward” amplification loop for the initiation of mitochondrial apoptosis, bypassing the need for activator BH3s.

Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members prevent apoptosis through the sequestration of activator BH3s or BH3-exposed BAX/BAK monomers

Anti-apoptotic BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 sequester activator BH3s to prevent the initiation of BAX and BAK activation [8,13], providing frontline protection (Figs. 2A and 3). As the second line of defense, the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members can also sequester “BH3-exposed” BAX and BAK monomers to prevent the homo-oligomerization of BAX and BAK [9,15] (Figs. 2D and 3). The interaction between activator BH3s and anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members confers mutual inhibition because it not only prevents activator BH3s from activating BAX or BAK but also restrain the anti-apoptotics from sequestering “BH3-exposed” BAX or BAK monomers. BID, BIM, and PUMA can prevent BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 from sequestering BAX and BAK whereas NOXA can only inhibit MCL-1. This difference may contribute to the lower death-inducing activity of NOXA in comparison with BID, BIM, and PUMA. Consequently, Noxa deficiency only confers resistance to apoptosis in tissues or cell types that highly express NOXA, such as mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and the small intestines [9]. Notably, BCL-XL is superior to BCL-2 and MCL-1 in preventing apoptosis due to its dual inhibition of BAX and BAK and higher protein stability [9,42]. BCL-2 can only inhibit BAX but not BAK [9,42] whereas MCL-1 is prone to degradation upon death signals [43].

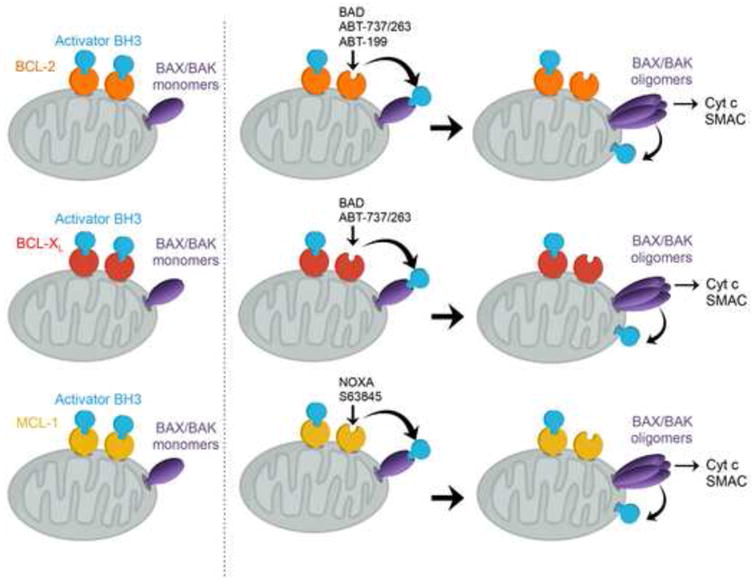

Indirect activation of BAX and BAK by inactivator BH3s

The ability of BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 to sequester tBID/BIM/PUMA is further modulated by “inactivator” BH3s through high-affinity, competitive binding (Figs. 3 and 4). Specifically, BAD, BMF, BIK, and HRK (DP5) displace sequestered BID/BIM/PUMA from BCL-2/BCL-XL and thereby activate BAX/BAK indirectly [9,13]. NOXA is unique among all BH3s in that it can prevent MCL-1 from sequestering BID, BIM, and PUMA due to its high binding affinity to MCL-1 [13]. Hence, NOXA is both an activator and inactivator BH3. Notably, deficiency of Bid, Bim, Puma, and Noxa abrogates apoptosis triggered by overexpression of BAD, BMF, BIK or HRK [9], supporting the BH3 hierarchy in which activator BH3s function downstream of inactivator BH3s. Hence, the observation that BH3 peptides of some inactivator BH3s can induce BAX- or BAK-dependent liposome permeabilization is a purely in vitro phenomenon [44].

Figure 4. Indirect activation of BAX or BAK by inactivator BH3s and BH3 mimetics.

Anti-apoptotic BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 preserve mitochondrial integrity by sequestering activator BH3s to prevent activation of BAX and BAK. Pro-apoptotic “inactivator” BH3s, including BAD, BMF, BIK, and HRK, displace sequestered BID/BIM/PUMA from anti-apoptotic BCL-2 and BCL-XL, thereby activating BAX and BAK indirectly. NOXA is unique among all BH3s in that it can prevent MCL-1 from sequestering BID, BIM, and PUMA due to its high binding affinity to MCL-1. Hence, NOXA is both an activator and inactivator BH3. The BH3-mimietic small molecules ABT-737 and ABT-263 (navitoclax) activate BAX and BAK indirectly through displacing activator BH3s from BCL-2 and BCL-XL, whereas ABT-199 (venetoclax) selectively targets BCL-2. Selective inhibitors for BCL-XL or MCL-1 (S63845) with preclinical activity have also been generated.

BH3-independent autoactivation of BAX and BAK

The first unequivocal evidence of BH3-independent activation of BAX and BAK was not revealed until the generation of Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- QKO mice [9]. Autoactivation of BAX and BAK can occur in QKO cells when BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 are simultaneously decreased upon DNA damage or silenced by siRNA, albeit with slower kinetics compared to BH3-mediated activation [9]. In fact, silencing both BCL-XL and MCL-1 is sufficient to trigger BAK autoactivation due to the inability of BCL-2 to bind BAK. Similar findings were shown in cells deficient for eight canonical BH3s created by genome editing [45]. The MOM appears to provide an important platform for the autoactivation of BAX and BAK, which is consistent with the “embedded together” model that emphasizes the influence of the membrane milieu on BCL-2 family interactions [46]. However, autoactivation of BAX and BAK appears less efficient in part because only a small fraction of BAX and BAK expose their BH3 domain, which is sequestered by anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members in viable cells. Liberation of the small fraction, “BH3-exposed” BAX or BAK monomers from the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members is sufficient to induce a “feed-forward” amplification loop for the initiation of mitochondrial apoptosis. Therefore, activator BH3s function as catalysts for BAX and BAK activation by inducing the BH3 exposure of BAX and BAK while simultaneously restraining anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members. The presence of heterodimers between multidomain anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic members in QKO cells suggests that exposure of the BH3 domain in BAX and BAK can be generated independently of activator BH3s. Potential mechanisms include protein misfolding, post-translational modifications, oxidative stress, and physical stress such as heat or changes in intracellular pH [23]. It is possible that these heterodimers also have non-apoptotic functions in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis, such as calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial fission and fusion [47,48]. Retrotranslocation of BAX from the mitochondria to the cytosol mediated by BCL-XL appears to offer a means to reduce the BAX/BCL-XL heterodimers in the MOM [49].

Mouse genetic studies support the interconnected hierarchical model

Over the years, the mouse genetic studies of BCL-2 family proteins have provided the ultimate validations for in vitro mechanistic studies. Consistent with the higher and broader expression of Bim than other BH3s as well as its activator BH3 activity, Bim-/- mice display the most severe phenotypes compared to other single BH3 KOs, developing lymphoid hyperplasia and fatal autoimmune diseases [50]. Puma deficiency exacerbates the lymphoid hyperplasia and apoptotic defects of Bim KO mice [51], and mice lacking Bid, Bim, and Puma display even more severe defects and recapitulate the developmental defects of Bax-/-Bak-/- mice, including perinatal embryonic lethality, persistent interdigital webs and imperfortate vagina [6,52]. Triple deficiency of Bid, Bim, and Puma also completely abrogates BAX/BAK-dependent apoptosis in cerebellar granule neurons [52]. Due to the unique high expression of NOXA in MEFs, Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- but not Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/- MEFs are as resistant as Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs to apoptosis triggered by ER stress and deprivation of growth factors or nutrients [9]. However, genotoxic stress can induce autoactivation of BAX/BAK through downregulation of BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 in Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- MEFs [9]. Interestingly, DNA damage-induced downregulation of BCL-2 and BCL-XL is not observed in T-cells or the small intestine. Consequently, quadruple deficiency of Bid, Bim, Puma, and Noxa provides comparable protection as double deficiency of Bax and Bak against irradiation-induced apoptosis in the small intestine [9]. Consistent with the low expression of NOXA in lymphocytes and the absence of BAX/BAK activation detected in Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/- T-cells [52], Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/- T-cells are as resistant as Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- T-cells to various apoptotic signals [9]. However, double deficiency of Bax and Bak incurs more severe embryonic lethality than quadruple deficiency of Bid, Bim, Puma, and Noxa [6,9], likely reflecting the presence of BAX/BAK autoactivation in certain tissues in response to developmental cues. Alternatively, non-apoptotic functions of BAX and BAK, such as regulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion or ER calcium homeostasis [47,48], may account for the more severe embryonic lethality of Bax-/-Bak-/- mice.

The findings that Bim deficiency prevents the development of polycystic kidney disease and loss of melanocytes in Bcl-2-/- mice [53] support the concept that sequestration of BIM by BCL-2 prevents apoptosis. In addition, mice harboring the death-competent BakQ75L mutation that abrogates the BCL-XL/BAK but not MCL-1/BAK or BAK/BAK interaction display reduced T-cell and platelet survival and increased sensitivity to various apoptotic stimuli [54], providing in vivo evidence that inhibition of BAK by BCL-XL contributes to apoptosis regulation. Overall, the mouse genetic studies substantiate the interconnected hierarchical regulation of apoptosis by the BCL-2 family.

Therapeutic targeting of BCL-2 family interactions

To abrogate apoptotic checkpoints, cancer cells often overexpress anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins through genetic mutations such as chromosomal translocations involving BCL-2 or amplification of BCL-XL and MCL-1 [4,55]. Counterintuitively, cancer cells also commonly express higher levels of BIM and PUMA that are transcriptionally activated by E2F1 upon malignant transformation [56] and sequestered by anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members as inert complexes. Hence, many cancer cells are likely “primed” to undergo apoptosis upon the administration of BAD and NOXA mimetics that displace BIM/PUMA from BCL-2/BCL-XL and MCL-1, respectively, to activate the BAX/BAK apoptotic gateway (Fig. 4).

Structure-based screening efforts targeting the hydrophobic dimerization groove of BCL-XL have led to the development of the first specific small molecule inhibitor of the BCL-2 family, ABT-737 [57]. ABT-737 and its orally bioavailable analog ABT-263 (navitoclax) function like BAD mimetics that bind and inhibit BCL-2, BCL-XL, and BCL-W, but not MCL-1 or A1 [57,58]. Although navitoclax shows promising clinical activity, it induces a dose-dependent rapid thrombocytopenia as an on-target result of BCL-XL inhibition. This spurred the development of ABT-199 (venetoclax or GDC-0199), a platelet-sparing, selective BCL-2 inhibitor [59]. Venetoclax has exhibited remarkable therapeutic efficacy for relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [60], resulting in its approval by the FDA for the treatment of CLL patients with 17p deletion. Similar to inactivator BH3s, ABT-263 activates BAX/BAK indirectly through the displacement of activator BH3s from BCL-2 and BCL-XL (Fig. 4). Hence, low expression of activator BH3s in cancers, particularly BIM, confers resistance to ABT-263 [42]. Another therapeutic limitation of ABT-263 is its inability to disrupt the BCL-XL/BAK interaction such that overexpression of BCL-XL confers resistance to ABT-263 [42]. Selective inhibitors of BCL-XL (A-1331852) or MCL-1 (S63845) with robust preclinical activity have also been generated [61,62]. The current progress of development of non-canonical inhibitors of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members, along with emerging approaches to target pro-apoptotic BAX and BAK, are discussed in detail elsewhere [63].

With BH3 mimetics entering the clinic, one major challenge is how to identify patients who will respond to a specific BCL-2 family inhibitor. Differential addiction of cancer cells to anti-apoptotic BCL-2, BCL-XL, or MCL-1 was reported in a panel of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cell lines and found to correlate with the respective protein expression ratio [42]. If a given cell predominantly expresses a specific anti-apoptotic BCL-2 member, it will be addicted to that specific anti-apoptotic BCL-2 member for survival. BH3 profiling is a powerful tool to assess the baseline “mitochondrial priming” or apoptotic sensitivity of cancer cells to cancer therapeutics [64], whereas dynamic BH3 profiling can be used to measure the changes in apoptotic priming in response to therapeutic agents [65]. However, both predict the overall apoptotic sensitivity rather than the addiction to individual anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members. The development of protein expression-based biomarkers to predict the differential addiction of human tumors to individual anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members will guide the future practice of precision cancer medicine targeting the BCL-2 family.

The applications of BH3 mimetics as therapeutics extend beyond cancer treatment. ABT-263 was identified as a potent senolytic agent that selectively eliminates senescent cells [66], potentially expanding its utility to treating age-related pathologies. Given that some BCL-2 family proteins can regulate autophagy, mitophagy, mitochondrial metabolism, mitochondrial dynamics, calcium homeostasis, and peroxisomal membrane permeability [47,48,67-69], BH3 mimetics may provide useful tools for manipulating these non-apoptotic processes for future studies and therapeutic interventions. For example, stapled peptides modeled after the phospho-BAD BH3 helix can enhance insulin secretion and β cell survival, and improve functional β cell mass in diabetes due to activation of glucokinase by phosphorylation of the BAD BH3 domain at Ser155 [70].

Conclusions

Three decades after the term “apoptosis or programmed cell death” first captured the world's attention, intense research efforts encompassing molecular biology, biochemistry, structural biology, and genetically engineered mouse models have unveiled an intricately wired, interacting, regulatory network centered on the BCL-2 family proteins that adjudicate cell survival or death decisions. Importantly, this comprehensive knowledge has not only satiated humanity's curiosity for the unknown but also laid the foundations and provided the much needed roadmaps for the continuous development and mechanism-based application of small-molecule BH3 mimetics in cancer therapy. In the next 10 years, we envision that many long unresolved questions will be answered with new pharmacological tools and research technologies, yet novel opportunities will arise to challenge existing and inspire new cell death researchers.

BH3s initiate apoptosis by activating BAX/BAK or inactivating anti-death BCL-2s.

BID, BIM, PUMA, and NOXA directly induce stepwise bimodal activation of BAX and BAK.

BH3-independent autoactivation of BAX/BAK occurs when anti-death BCL-2s are decreased.

Anti-death BCL-2 members sequester BH3s or BH3-exposed BAX/BAK to inhibit apoptosis.

BCL-2 family interactions dictate the efficacy of BH3 mimetics in cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to all the investigators whose research could not be appropriately cited owing to space limitation. This work was supported by a grant to E. Cheng from the NIH (R01CA125562).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

- 1.Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2922–2933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou M, Li Y, Hu Q, Bai Xc, Huang W, Yan C, Scheres SH, Shi Y. Atomic structure of the apoptosome: mechanism of cytochrome c-and dATP-mediated activation of Apaf-1. Genes & development. 2015;29:2349–2361. doi: 10.1101/gad.272278.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 initiates a new category of oncogenes: regulators of cell death. Blood. 1992;80:879–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brem EA, Letai A. BOK: Oddball of the BCL-2 Family. Trends in cell biology. 2016;26:389–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindsten T, Ross AJ, King A, Zong WX, Rathmell JC, Shiels HA, Ulrich E, Waymire KG, Mahar P, Frauwirth K, et al. The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bak and Bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng EH, Wei MC, Weiler S, Flavell RA, Mak TW, Lindsten T, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2, BCL-X(L) sequester BH3 domain-only molecules preventing BAX- and BAK-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2001;8:705–711. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Chen HC, Kanai M, Inoue-Yamauchi A, Tu HC, Huang Y, Ren D, Kim H, Takeda S, Reyna DE, Chan PM. An interconnected hierarchical model of cell death regulation by the BCL-2 family. Nature cell biology. 2015;17:1270–1281. doi: 10.1038/ncb3236. The goals of this paper are to identify the full repertoire of activator BH3s, to generate knockout mice deficient for all activator BH3s, and to determine whether BAX and BAK can be activated in the absence of activator BH3s. The authors show that NOXA, joining BID, BIM, and PUMA, is an activator BH3. Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- mice are generated and compared to Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/- or Bax-/-Bak-/- mice. BID, BIM, PUMA, and NOXA directly induce stepwise, bimodal activation of BAX and BAK. BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 inhibit both modes of BAX and BAK activation by sequestering activator BH3s and “BH3-exposed” monomers of BAX/BAK, respectively. BCL-XL is superior to BCL-2 and MCL-1 in preventing apoptosis due to its dual inhibition of BAX and BAK and higher protein stability. Furthermore, autoactivation of BAX and BAK can occur independently of activator BH3s through downregulation of BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1, albeit at slower kinetics compared to BH3-mediated activation. Overexpression of inactivator BH3s, including BAD, BMF, BIK, and HRK, fails to kill Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- cells, supporting that activator BH3s function downstream of inactivator BH3s. This paper presents the first unequivocal evidence of BH3-independent activation of BAX and BAK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bean GR, Ganesan YT, Dong Y, Takeda S, Liu H, Chan PM, Huang Y, Chodosh LA, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJ, et al. PUMA and BIM are required for oncogene inactivation-induced apoptosis. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra20. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puthalakath H, O'Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L, Kelly PN, Huntington ND, Hughes PD, Michalak EM, McKimm-Breschkin J, Motoyama N. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 2007;129:1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehan E, Bassermann F, Guardavaccaro D, Vasiliver-Shamis G, Cohen M, Lowes KN, Dustin M, Huang DC, Taunton J, Pagano M. βTrCP-and Rsk1/2-mediated degradation of BimEL inhibits apoptosis. Molecular cell. 2009;33:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim H, Rafiuddin-Shah M, Tu HC, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH. Hierarchical regulation of mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis by BCL-2 subfamilies. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1348–1358. doi: 10.1038/ncb1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Letai A, Bassik MC, Walensky LD, Sorcinelli MD, Weiler S, Korsmeyer SJ. Distinct BH3 domains either sensitize or activate mitochondrial apoptosis, serving as prototype cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czabotar PE, Lessene G, Strasser A, Adams JM. Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: implications for physiology and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:49–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czabotar PE, Westphal D, Dewson G, Ma S, Hockings C, Fairlie WD, Lee EF, Yao S, Robin AY, Smith BJ, et al. Bax crystal structures reveal how BH3 domains activate Bax and nucleate its oligomerization to induce apoptosis. Cell. 2013;152:519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moldoveanu T, Grace CR, Llambi F, Nourse A, Fitzgerald P, Gehring K, Kriwacki RW, Green DR. BID-induced structural changes in BAK promote apoptosis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:589–597. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards AL, Gavathiotis E, LaBelle JL, Braun CR, Opoku-Nsiah KA, Bird GH, Walensky LD. Multimodal interaction with BCL-2 family proteins underlies the proapoptotic activity of PUMA BH3. Chem Biol. 2013;20:888–902. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leshchiner ES, Braun CR, Bird GH, Walensky LD. Direct activation of full-length proapoptotic BAK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E986–995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214313110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brouwer JM, Westphal D, Dewson G, Robin AY, Uren RT, Bartolo R, Thompson GV, Colman PM, Kluck RM, Czabotar PE. Bak core and latch domains separate during activation, and freed core domains form symmetric homodimers. Mol Cell. 2014;55:938–946. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki M, Youle RJ, Tjandra N. Structure of Bax: coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. Cell. 2000;103:645–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewson G, Kratina T, Sim HW, Puthalakath H, Adams JM, Colman PM, Kluck RM. To trigger apoptosis, Bak exposes its BH3 domain and homodimerizes via BH3:groove interactions. Mol Cell. 2008;30:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westphal D, Kluck RM, Dewson G. Building blocks of the apoptotic pore: how Bax and Bak are activated and oligomerize during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:196–205. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H, Tu HC, Ren D, Takeuchi O, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH. Stepwise activation of BAX and BAK by tBID, BIM, and PUMA initiates mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2009;36:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu NY, Sukumaran SK, Kerk SY, Yu VC. Baxbeta: a constitutively active human Bax isoform that is under tight regulatory control by the proteasomal degradation mechanism. Mol Cell. 2009;33:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai H, Smith A, Meng XW, Schneider PA, Pang YP, Kaufmann SH. Transient binding of an activator BH3 domain to the Bak BH3-binding groove initiates Bak oligomerization. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:39–48. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, Colman PM, Day CL, Adams JM, Huang DC. Differential targeting of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins by their BH3-only ligands allows complementary apoptotic function. Mol Cell. 2005;17:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Chipuk JE, Bonzon C, Sullivan BA, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. BH3 domains of BH3-only proteins differentially regulate Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization both directly and indirectly. Mol Cell. 2005;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Certo M, Del Gaizo Moore V, Nishino M, Wei G, Korsmeyer S, Armstrong SA, Letai A. Mitochondria primed by death signals determine cellular addiction to antiapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Garner TP, Reyna DE, Priyadarshi A, Chen HC, Li S, Wu Y, Ganesan YT, Malashkevich VN, Cheng EH, Gavathiotis E. An autoinhibited dimeric form of BAX regulates the BAX activation pathway. Molecular cell. 2016;63:485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.010. Cytosolic BAX can form autoinhibited asymetric dimers in selected cell lines, in which dissociation of inactive BAX dimers to monomers must occur before BAX can be activated by BH3s. The crystal structure of full-length BAX forming an asymetric dimer reveals that the α9 helix from one protomer binds the N-terminal trigger site of the other protomer in an orientation that preserves the α1- α2 loop in a closed and inactive conformation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng EH, Sheiko TV, Fisher JK, Craigen WJ, Korsmeyer SJ. VDAC2 inhibits BAK activation and mitochondrial apoptosis. Science. 2003;301:513–517. doi: 10.1126/science.1083995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gavathiotis E, Suzuki M, Davis ML, Pitter K, Bird GH, Katz SG, Tu HC, Kim H, Cheng EH, Tjandra N, et al. BAX activation is initiated at a novel interaction site. Nature. 2008;455:1076–1081. doi: 10.1038/nature07396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gavathiotis E, Reyna DE, Davis ML, Bird GH, Walensky LD. BH3-triggered structural reorganization drives the activation of proapoptotic BAX. Mol Cell. 2010;40:481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Alsop AE, Fennell SC, Bartolo RC, Tan IK, Dewson G, Kluck RM. Dissociation of Bak α1 helix from the core and latch domains is required for apoptosis. Nature communications. 2015;6:6841. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7841. Using conformation-specific antibodies, the authors demonstrate the exposure of the α1 helix of BAK upon activation by BID. They show that disulfide tethering of α1 to α2 or α6 blocks cytochrome c release, suggesting that α1 dissociation is required for further conformational changes during apoptosis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dewson G, Kratina T, Czabotar P, Day CL, Adams JM, Kluck RM. Bak activation for apoptosis involves oligomerization of dimers via their α6 helices. Molecular cell. 2009;36:696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandal T, Shin S, Aluvila S, Chen HC, Grieve C, Choe JY, Cheng EH, Hustedt EJ, Oh KJ. Assembly of Bak homodimers into higher order homooligomers in the mitochondrial apoptotic pore. Scientific reports. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep30763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito M, Korsmeyer SJ, Schlesinger PH. BAX-dependent transport of cytochrome c reconstituted in pure liposomes. Nature cell biology. 2000;2:553–555. doi: 10.1038/35019596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuwana T, Mackey MR, Perkins G, Ellisman MH, Latterich M, Schneiter R, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. Bid, Bax, and lipids cooperate to form supramolecular openings in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Cell. 2002;111:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uren RT, O'Hely M, Iyer S, Bartolo R, Shi MX, Brouwer JM, Alsop AE, Dewson G, Kluck RM. Disordered clusters of Bak dimers rupture mitochondria during apoptosis. eLife. 2017;6:e19944. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groβe L, Wurm CA, Brüser C, Neumann D, Jans DC, Jakobs S. Bax assembles into large ring-like structures remodeling the mitochondrial outer membrane in apoptosis. The EMBO journal. 2016;35:402–413. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salvador-Gallego R, Mund M, Cosentino K, Schneider J, Unsay J, Schraermeyer U, Engelhardt J, Ries J, GarcíanSáez AJ. Bax assembly into rings and arcs in apoptotic mitochondria is linked to membrane pores. The EMBO journal. 2016;35:389–401. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42**.Inoue-Yamauchi A, Jeng PS, Kim K, Chen HC, Han S, Ganesan YT, Ishizawa K, Jebiwott S, Dong Y, Pietanza MC. Targeting the differential addiction to anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family for cancer therap. Nature Communications. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms16078. ncomms16078. Using small cell lung cancer (SCLC) as a model, the authors demonstrate the presence of differential addiction of cancer cells to anti-apoptotic BCL-2, BCL-Xl, or MCL-1, which correlates with the respective protein expression ratio. The authors show that ABT-263 activates BAX and BAK indirectly through the displacement of activator BH3s from BCL-2 and BCL-Xl. Hence, low expression of activator BH3s in cancers, particularly BIM, confers resistance to ABT-263. They also identify a previously unrecognized therapeutic limitation of ABT-263, which is caused by its inability to disrupt the BCL-XL/BAK interaction such that overexpression of BCL-XL confers resistance to ABT-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perciavalle RM, Opferman JT. Delving deeper: MCL-1′s contributions to normal and cancer biology. Trends in cell biology. 2013;23:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Du H, Wolf J, Schafer B, Moldoveanu T, Chipuk JE, Kuwana T. BH3 domains other than Bim and Bid can directly activate Bax/Bak. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:491–501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45**.O'Neill KL, Huang K, Zhang J, Chen Y, Luo X. Inactivation of prosurvival Bcl-2 proteins activates Bax/Bak through the outer mitochondrial membrane. Genes & development. 2016;30:973–988. doi: 10.1101/gad.276725.115. HCT116 cells deficient for eight canonical BH3s (OctaKO) generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system undergo apoptosis following inactivation of BCL-XL and MCL-1, consistent with the findings derived from Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- MEFs. The authors subsequently generate HCT116 cells deficient for 10 BH3s (8 canonical BH3s plus BNIP3 and NIX), 5 anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members, BAX, and BAK, which is called “BCL-2 allKO”. Re-expression of BAX or BAK, but not BAX or BAK mutant without the C-terminal transmembrane anchor, in BCL-2 allKO cells induces spontaneous activation and homo-oligomerization of BAX or BAK, supporting the importance of MOM as a platform for BAX/BAK activation. These findings are consistent with the autoactivation of BAX and BAK observed in Bid-/-Bim-/-Puma-/-Noxa-/- MEFs with simultaneous downregulation of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leber B, Lin J, Andrews DW. Embedded together: the life and death consequences of interaction of the Bcl-2 family with membranes. Apoptosis. 2007;12:897–911. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0746-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scorrano L, Oakes SA, Opferman JT, Cheng EH, Sorcinelli MD, Pozzan T, Korsmeyer SJ. BAX and BAK regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+: a control point for apoptosis. Science. 2003;300:135–139. doi: 10.1126/science.1081208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinou JC, Youle RJ. Mitochondria in apoptosis: Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev Cell. 2011;21:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edlich F, Banerjee S, Suzuki M, Cleland MM, Arnoult D, Wang C, Neutzner A, Tjandra N, Youle RJ. Bcl-x(L) retrotranslocates Bax from the mitochondria into the cytosol. Cell. 2011;145:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouillet P, Metcalf D, Huang DC, Tarlinton DM, Kay TW, Köntgen F, Adams JM, Strasser A. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 relative Bim required for certain apoptotic responses, leukocyte homeostasis, and to preclude autoimmunity. Science. 1999;286:1735–1738. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erlacher M, Labi V, Manzl C, Böck G, Tzankov A, Häcker G, Michalak E, Strasser A, Villunger A. Puma cooperates with Bim, the rate-limiting BH3-only protein in cell death during lymphocyte development, in apoptosis induction. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203:2939–2951. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ren D, Tu HC, Kim H, Wang GX, Bean GR, Takeuchi O, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH. BID, BIM, and PUMA are essential for activation of the BAX- and BAK-dependent cell death program. Science. 2010;330:1390–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.1190217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bouillet P, Cory S, Zhang LC, Strasser A, Adams JM. Degenerative disorders caused by Bcl-2 deficiency prevented by loss of its BH3-only antagonist Bim. Developmental cell. 2001;1:645–653. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54**.Lee EF, Grabow S, Chappaz S, Dewson G, Hockings C, Kluck RM, Debrincat MA, Gray DH, Witkowski MT, Evangelista M. Physiological restraint of Bak by Bcl-xL is essential for cell survival. Genes & development. 2016;30:1240–1250. doi: 10.1101/gad.279414.116. The authors characterize the apoptotic phenotypes of a mouse strain harboring the death-competent BakQ75L mutation generated through N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis. Both the mouse BAK Q75L mutation and the equivalent human BAK Q77L mutation abrogate the interaction between BAK and BCL-XL but not the homo-dimerization of BAK or the interaction between BAK and MCL-1. Cells derived from BakQ75L mice are more sensitive to various apoptotic stimuli and BakQ75L mice display reduced T-cell and platelet survival, consistent with increased apoptosis caused by reduced restraint of BAK by BCL-XL. Overall, this paper provides in vivo evidence that inhibition of BAK by BCL-XL contributes to apoptosis regulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, Barretina J, Boehm JS, Dobson J, Urashima M, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hershko T, Ginsberg D. Up-regulation of Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3)-only proteins by E2F1 mediates apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:8627–8634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, Bruncko M, Deckwerth TL, Dinges J, Hajduk PJ, et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature. 2005;435:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature03579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tse C, Shoemaker AR, Adickes J, Anderson MG, Chen J, Jin S, Johnson EF, Marsh KC, Mitten MJ, Nimmer P, et al. ABT-263: a potent and orally bioavailable Bcl-2 family inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3421–3428. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, Ackler SL, Catron ND, Chen J, Dayton BD, Ding H, Enschede SH, Fairbrother WJ, et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat Med. 2013;19:202–208. doi: 10.1038/nm.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60**.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, Kahl BS, Puvvada SD, Gerecitano JF, Kipps TJ, Anderson MA, Brown JR, Gressick L, et al. Targeting BCL2 with Venetoclax in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513257. This paper describes the landmark phase 1 clinical trial of venetoclax (the small molecule BCL-2 inhibitor ABT-199) in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL. The single-agent activity of venetoclax in relapsed CLL patients is outstanding with a 79% response rate and manageable secondary effects. The clinical trial results have led to the FDA approval of venetoclax in April 2016 for its use in CLL patients with 17p chromosomal deletion, a biomarker for TP53 loss and poor prognosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leverson JD, Phillips DC, Mitten MJ, Boghaert ER, Diaz D, Tahir SK, Belmont LD, Nimmer P, Xiao Y, Ma XM, et al. Exploiting selective BCL-2 family inhibitors to dissect cell survival dependencies and define improved strategies for cancer therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:279r. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4642. a240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62*.Kotschy A, Szlavik Z, Murray J, Davidson J, Maragno AL, Le Toumelin-Braizat G, Chanrion M, Kelly GL, Gong JN, Moujalled DM. The MCL1 inhibitor S63845 is tolerable and effective in diverse cancer models. Nature. 2016;538:477–482. doi: 10.1038/nature19830. This paper describes the discovery of the first specific and potent small molecule inhibitor of MCL-1 with in vivo antitumor acitivity as a single agent and an acceptable safety margin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garner TP, Lopez A, Reyna DE, Spitz AZ, Gavathiotis E. Progress in targeting the BCL-2 family of proteins. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2017;39:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deng J, Carlson N, Takeyama K, Dal Cin P, Shipp M, Letai A. BH3 profiling identifies three distinct classes of apoptotic blocks to predict response to ABT-737 and conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65*.Montero J, Sarosiek KA, DeAngelo JD, Maertens O, Ryan J, Ercan D, Piao H, Horowitz NS, Berkowitz RS, Matulonis U. Drug-induced death signaling strategy rapidly predicts cancer response to chemotherapy. Cell. 2015;160:977–989. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.042. This paper describes a powerful tool named “dynamic BH3 profiling”, which can be used to measure the changes in apoptotic priming in response to therapeutic agents and thereby predict response to cancer therapeutics in vivo and in the clinic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66*.Chang J, Wang Y, Shao L, Laberge RM, Demaria M, Campisi J, Janakiraman K, Sharpless NE, Ding S, Feng W. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nature medicine. 2016;22:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nm.4010. A screen identifies ABT-263 as a potent senolytic agent that selectively and potently kills senescent cells across numerous cell types. The authors explore its potential as a therapeutic to rejuvenate stem cells in aged mice and mitigate radiation injury. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gross A, Katz SG. Non-apoptotic functions of BCL-2 family proteins. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2017 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68*.Hosoi Ki, Miyata N, Mukai S, Furuki S, Okumoto K, Cheng EH, Fujiki Y. The VDAC2–BAK axis regulates peroxisomal membrane permeability. J Cell Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1083/jcb.201605002. jcb. 201605002. VDAC2 stabilizes the mitochondrial association of BAK and loss of VDAC2 shifts the localization of BAK from mitochondria to peroxisomes, resulting in peroxisomal permeabilization and release of peroxisomal proteins to cytosol. BAK-mediated peroxisomal membrane permeability can be inhibted by BCL-XL and MCL-1 but not BCL-2, consistent with their interaction pattern.Overexpression of BIM and PUMA permeabilizes peroxisomes in a BAK-dependent manner, which is analogous to the activation of BAK-dependent MOMP by BIM and PUMA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perciavalle RM, Stewart DP, Koss B, Lynch J, Milasta S, Bathina M, Temirov J, Cleland MM, Pelletier S, Schuetz JD, et al. Anti-apoptotic MCL-1 localizes to the mitochondrial matrix and couples mitochondrial fusion to respiration. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:575–583. doi: 10.1038/ncb2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ljubicic S, Polak K, Fu A, Wiwczar J, Szlyk B, Chang Y, Alvarez-Perez JC, Bird GH, Walensky LD, Garcia-Ocaña A. Phospho-BAD BH3 mimicry protects β cells and restores functional β cell mass in diabetes. Cell reports. 2015;10:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]