Abstract

Purpose

Employment opportunities for graduating pediatric surgeons vary from year to year. Significant turnover among new employees indicates fellowship graduates may be unsophisticated in choosing job opportunities which will ultimately be satisfactory for themselves and their families. The purpose of this study was to assess what career, life, and social factors contributed to the turnover rates among pediatric surgeons in their first employment position.

Methods

American Pediatric Surgical Association members who completed fellowship training between 2011 and 2016 were surveyed voluntarily. Only those who completed training in a pediatric surgery fellowship sanctioned by the American Board of Surgery and whose first employment involved the direct surgical care of patients were included. The survey was completed electronically and the results were evaluated using chi-squared analysis to determine which independent variables contributed to a dependent outcome of changing place of employment.

Results

110 surveys were returned with respondents meeting inclusion criteria. 13 (11.8%) of the respondents changed jobs within the study period and 97 (88.2%) did not change jobs. Factors identified that likely contributed to changing jobs included a perceived lack of opportunity for career [p = <0.001] advancement and the desire to no longer work at an academic or teaching facility [p = 0.013]. Others factors included excessive case load [p = 0.006]; personal conflict with partners or staff [p = 0.007]; career goals unfulfilled by practice [p = 0.011]; lack of mentor-ship in partners [p = 0.026]; and desire to be closer to the surgeon’s or their spouse’s family [p = 0.002].

Conclusions

Several factors appear to play a role in motivating young pediatric surgeons to change jobs early in their careers. These factors should be taken into account by senior pediatric fellows and their advisors when considering job opportunities.

Type of Study

Survey.

Level of Evidence

IV.

Keywords: First jobs, Pediatric surgeons, Membership committee, Job satisfaction

Pediatric surgery fellowships remain one of the most competitive and highly sought-after training programs in medicine, and the number of surgeons who care for pediatric patients is expected to rise [1]. The forty to fifty fellowship graduates from these programs are in demand for jobs in all types of practice settings across the United States [2]. Despite the ubiquitous need for pediatric surgical care and a seemingly robust job market, it is unclear how satisfied pediatric surgeons are with their first employment opportunity. Burnout rates in surgery are fairly high, and finding ways to maintain satisfactory careers in surgery are important [3]. Of the surgical subspecialties, pediatric surgeons tend to have higher career satisfaction rates [4]. Although job satisfaction is a highly multifactorial concept, its components have been studied in many industries, and are, in fact, quite quantifiable. As with many other careers, it could be presumed that practice environments, interpersonal disagreements, compensation, lack of opportunity, and external circumstances all could influence one’s desire to change places of employment.

Until this point however, studies investigating employment patterns and job satisfaction among pediatric surgeons have been sparse. A few select studies have looked at employment statistics and the job market for pediatric surgeons, but these articles are older and do not seek to answer why these trends are taking place [2,5]. One more recent study of surgeons deduced that work-environment variables such as autonomy, patient diversity, patient ownership, safe patient load, hospital culture, hospital support, camaraderie, and salary were statistically significant in influencing positive job satisfaction [6]. A more thorough analysis of job turnover could help characterize the values of this highly accomplished and motivated subset of surgeons. It could aid in profiling recent program graduates, assessing behavioral trends in employment, and ultimately help hiring practices better understand their applicants. Such information could be important for senior pediatric surgery fellows and their advisors as they weigh employment opportunities. We therefore hypothesized that job turnover among new pediatric surgery graduates would be associated with specific, identifiable characteristics that would be different from those who did not change employment.

1. Methods

In order to quantitatively assess which factors contributed toward the decision by a surgeon to stay at his or her first place of employment or change jobs, an online survey was created. This was distributed via e-mail to members of the American Pediatric Surgical Association who finished their fellowship training between 2011 and 2016. Inclusion criteria were (1) having completed a pediatric surgery fellowship which was sanctioned by the American Board of Surgery and (2) having direct patient care be part of their first employment position. The study was submitted to the Indiana University Institutional Review Board and was deemed to be exempt.

Participation in the survey was voluntary and identifying information including age and gender was not collected for the sake of anonymity. The survey began with an initial branch-point to determine if the respondent (1) did, or (2) did not change jobs after being hired by their first employer. Respondents were then asked questions in one of two pathways based on this answer. These subsequent questions were equivalent concepts, but worded appropriately depending on whether the person had or had not changed jobs. Subjects were asked eight multiple choice questions and fifteen true–false questions (See Appendix).

Responses were initially recorded and quantified by the survey website and these data were then formatted in a database for organization and review. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS 24 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). Chi-square test of homogeneity was used to assess differences in responses between the two groups to each question, with statistical significance defined by p < 0.05. Each question pertained to a separate factor which was speculated to affect job satisfaction or choice of employment. The different answer choices were treated as independent variables, with the dependent outcome being changing employment.

2. Results

2.1. Study cohort

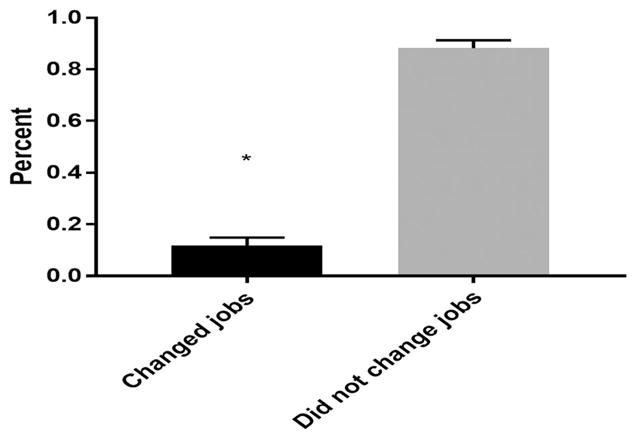

Of the 962 paying members of APSA in 2016, 222 were candidate or regular members who completed fellowship training within five years of the survey, and therefore, were deemed eligible to participate. One hundred and ten responded to the survey for a response rate of 53%. Of the 110 respondents, 13 (11.8%) changed jobs within the study period, while 97 (88.2%) did not (Fig. 1, p < 0.05). For some questions, the number of responses does not equal the total number of expected participants owing to some questions being unanswered.

Fig. 1.

11.8% of those who responded to the survey changed jobs within the first five years of practice. Not surprisingly, the majority of respondents (88.2%) maintained their first job within the first five years of practice. * = p < 0.05.

2.2. People and partners (Table 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of people and partners that may have led to changing employment.

| Job Change in First Five Years? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No | Yes | P Value | ||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Count | Column N % | Count | Column N % | |||

| Which of the following best describes the nature of your partnership at your current institution? | Unanswered | 1 | 1.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.708 |

| The number of partners is balanced and adequate. | 53 | 54.60% | 7 | 53.80% | ||

| There are too few partners. | 31 | 32.00% | 3 | 23.10% | ||

| There are too many partners. | 12 | 12.40% | 3 | 23.10% | ||

| My salary and benefits at my institution are: | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.368 |

| Above national standards | 18 | 18.60% | 4 | 30.80% | ||

| Below national standards | 24 | 24.70% | 3 | 23.10% | ||

| Comparable to national standards | 33 | 34.00% | 6 | 46.20% | ||

| I am unaware of how my salary/benefits compare to national standards. | 15 | 15.50% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| Personal conflict exists between myself and my partners or other staff members. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.007 |

| FALSE | 74 | 76.30% | 5 | 38.50% | ||

| TRUE | 16 | 16.50% | 7 | 53.80% | ||

| There is a lack of mentorship in the partners of my practice. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.026 |

| FALSE | 65 | 67.00% | 4 | 30.80% | ||

| TRUE | 25 | 25.80% | 8 | 61.50% | ||

| The health of a loved one, friend, or family member could be a factor in my decision to change employers. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.066 |

| FALSE | 51 | 52.60% | 11 | 84.60% | ||

| TRUE | 39 | 40.20% | 1 | 7.70% | ||

| Divorce played a role in my desire to remain in my current position. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.757 |

| FALSE | 86 | 88.70% | 12 | 92.30% | ||

| TRUE | 4 | 4.10% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| The job opportunities or career goals of my spouse played a role in the decision to stay in my first place of employment. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.751 |

| FALSE | 69 | 71.10% | 8 | 61.50% | ||

| TRUE | 21 | 21.60% | 4 | 30.80% | ||

The people with whom the pediatric surgeon interacted with on a daily basis were presumed to have a fairly large impact on job satisfaction. These people included work partners as well as spouses and family members. No statistically significant differences were found between surgeons who changed jobs and those who did not when comparing if they had subjectively too many or too few professional partners (p = 0.708). However, when assessing if personal conflict among partners or staff played a role in changing jobs, a significant difference was noted (p = 0.007). Sixteen (16.5%) surgeons staying at their jobs confirmed that conflict existed between their partners or other staff members, while 74 (76.3%) denied conflict. For surgeons who changed jobs, 7 (53.8%) confirmed conflict and 5 (38.5%) denied conflict.

Those who remained at their first job also felt that they had better mentorship (p = 0.026). Twenty-five (25.8%) surgeons who stayed felt that mentorship was lacking, while 65 (67.0%) felt that mentorship was adequate. For those who changed jobs, 8 (61.5%) felt that mentor-ship had been lacking while only 4 (30.8%) felt it was adequate.

Additionally, the contributions of spouses and family members to changing jobs were also assessed. Marital divorce, the career goals of the spouse, or the health of a loved one did not appear to play roles in first job changes.

2.3. Job characteristics (Table 2)

Table 2.

Job characteristics that may have led to changing employment.

| Job Change in First Five Years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No | Yes | P Value | ||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Count | Column N % | Count | Column N % | |||

| How many hospitals or outreach clinics are you required to cover? | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.169 |

| One | 17 | 17.50% | 2 | 15.40% | ||

| More than 5 | 3 | 3.10% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| Three to Five | 17 | 17.50% | 6 | 46.20% | ||

| Two to Three | 53 | 54.60% | 5 | 38.50% | ||

| The work load is shared equally by all of my partners. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.769 |

| FALSE | 32 | 33.00% | 3 | 23.10% | ||

| TRUE | 58 | 59.80% | 9 | 69.20% | ||

| The case load I am expected to maintain is excessive. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.006 |

| FALSE | 82 | 84.50% | 7 | 53.80% | ||

| TRUE | 8 | 8.20% | 5 | 38.50% | ||

| The scope of cases is too limited. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.242 |

| FALSE | 72 | 74.20% | 7 | 53.80% | ||

| TRUE | 18 | 18.60% | 5 | 38.50% | ||

| I am uncomfortable managing the acuity or complexity of the patients at my practice. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.595 |

| FALSE | 83 | 85.60% | 10 | 76.90% | ||

| TRUE | 7 | 7.20% | 2 | 15.40% | ||

| I am required to stay in-house for call duties at one or more of the hospitals I cover. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.776 |

| FALSE | 75 | 77.30% | 9 | 69.20% | ||

| TRUE | 15 | 15.50% | 3 | 23.10% | ||

Work characteristics of the position were also assessed. Factors included hospital coverage, workload, case load, acuity of cases, and scope of cases. On average those who stayed at their first job covered 2–3 hospitals, while those who changed jobs covered 3–5 hospitals. These differences were not statistically different (p = 0.169). 15.5% of job stayers noted that they were required to stay in-house for call at one or more of the hospitals that they covered while 23.1% of job changers had been required to stay in-house. There were no significant differences between job stayers or changers with regard to in-house call coverage (p = 0.776).

The overall workload among those who stayed at their initial practice and those who did not was not felt to be any different (p = 0.769). However, despite the lack of apparent difference, there appeared to be a higher number of job changers who felt that the case load that they were expected to maintain was excessively high (8.2% of job stayers vs. 38.5% of job changers). 84.5% of responding job stayers felt that the case load was not excessive while only 53.8% of job changers felt the same way (p = 0.006).

The scope of cases and the acuity of patient illness was also assessed. Being limited in scope of practice did not appear to be an influential factor in changing jobs (p = 0.242). Acuity of patient disease also did not appear to contribute to leaving one’s first position of employment (p = 0.595).

2.4. Amenities (Table 3)

Table 3.

Amenities that may have led to a change in employment.

| Job Change in First Five Years? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No | Yes | P Value | ||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Count | Column N % | Count | Column N % | |||

| Which of the following best describes your experience with the location of your employment? | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.154 |

| I am happy with my location and the amenities that are there. | 81 | 83.50% | 10 | 76.90% | ||

| My spouse or I are not comfortable having a family or raising children in the location. | 4 | 4.10% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| The city/town does not have enough amenities for me/my family to enjoy. | 3 | 3.10% | 2 | 15.40% | ||

| The town did not have enough amenities AND I did not feel comfortable having a family here | 2 | 2.10% | 1 | 7.70% | ||

| My salary and benefits at my institution are: | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.368 |

| Above national standards | 18 | 18.60% | 4 | 30.80% | ||

| Below national standards | 24 | 24.70% | 3 | 23.10% | ||

| Comparable to national standards | 33 | 34.00% | 6 | 46.20% | ||

| I am unaware of how my salary/benefits compare to national standards. | 15 | 15.50% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| I desire a job with more opportunity for a better work-life balance. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.502 |

| FALSE | 67 | 69.10% | 7 | 53.80% | ||

| TRUE | 23 | 23.70% | 5 | 38.50% | ||

| I want to relocate to a job closer to my family or my spouse’s family members. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.002 |

| FALSE | 77 | 79.40% | 5 | 38.50% | ||

| TRUE | 13 | 13.40% | 7 | 53.80% | ||

Respondents were prompted regarding the comfort and amenities of their initial employment location. Answers regarding the location of practice did not differ significantly (p = 0.154) between the two groups. However, when questioned about relocating closer to family, 13 (13.4%) of job stayers noted they would want to be closer to family compared to 7 (53.8%) of job changers. 77 (79.4%) job stayers noted that they did not have a desire to move closer to family, while only 5 (38.5%) of job changers did not want to be closer to family. These were statistically significant (p = 0.002).

Neither salary nor work life balance appeared to play a role in leaving one’s fist job (p = 0.368 and 0.502, respectively). No significant difference was found in perceptions of compensation relative to the national standard. When the true–false question was posed regarding work life balance, the majority of surgeons responded that they did not desire a better work life balance.

2.5. Career path (Table 4)

Table 4.

Career path characteristics that may have led to a change in employment.

| Job Change in First Five Years? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No | Yes | P Value | ||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Count | Column N % | Count | Column N % | |||

| Which of the following best describes your attitude regarding your practice environment? | Unanswered | 4 | 4.10% | 0 | 0.00% | <0.001 |

| Abundant opportunities are present in my environment, but hospital administration seems to lack support for pediatric surgery | 16 | 16.50% | 4 | 30.80% | ||

| I am happy in my current practice environment. | 53 | 54.60% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| I view my place of employment as a stepping-stone to a preferable position later. | 13 | 13.40% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| My practice environment did not play a role in my departure. | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 23.10% | ||

| There is a perceived lack of opportunity for career progression at my practice. | 11 | 11.30% | 6 | 46.20% | ||

| Which of the following explain your professional goals as they relate to your site of employment? | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.013 |

| I no longer desire to work at an academic/teaching facility and desire a private practice setting instead | 2 | 2.10% | 2 | 15.38% | ||

| I no longer desire to work at a private practice facility | 0 | 0% | 1 | 7.69% | ||

| My career goals changed after beginning my job. | 12 | 12.40% | 2 | 15.40% | ||

| My career goals have not changed since starting my position. | 69 | 71.10% | 7 | 53.80% | ||

| My research interests changed after beginning my job. | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | ||

| The following describes my experiences with research opportunities at my site of employment: | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 0 | 0.00% | 0.335 |

| I do not want research to be part of my practice. | 6 | 6.20% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| I feel my opportunities to pursue research are limited. | 22 | 22.70% | 6 | 46.20% | ||

| I would consider changing jobs for more preferred research opportunities/funding elsewhere. | 13 | 13.40% | 1 | 7.70% | ||

| Research opportunities are adequate/enjoyable at my current job. | 49 | 50.50% | 6 | 46.20% | ||

| My personal career goals are unfulfilled by the practice. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.011 |

| FALSE | 68 | 70.10% | 4 | 30.80% | ||

| TRUE | 22 | 22.70% | 8 | 61.50% | ||

| There is a lack of enthusiasm from hospital administration to support pediatric surgery endeavors. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.935 |

| FALSE | 50 | 51.50% | 6 | 46.20% | ||

| TRUE | 40 | 41.20% | 6 | 46.20% | ||

| I was not offered a renewal contract or the ability to become a partner. | Unanswered | 7 | 7.20% | 1 | 7.70% | 0.813 |

| FALSE | 87 | 89.70% | 12 | 92.30% | ||

| TRUE | 3 | 3.10% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

Opportunities for career advancement also played a role in one’s reasoning for changing employment. Sixteen (16.5%) surgeons who stayed at their job answered that abundant opportunities were present in their environment but hospital administration seemed to lack support for pediatric surgery, while 4 (30.8%) job changers felt similarly. Fifty-three (54.6%) surgeons who stayed responded that they were happy in their current practice environment, while zero respondents from those who changed jobs noted they had been happy. Thirteen (13.4%) surgeons who stayed noted that they viewed their current employment as a stepping stone to a preferable position, while zero surgeons who changed jobs noted that their first job was a stepping stone. None of the surgeons who stayed noted that practice environment would play a role in their departure, while 3 surgeons who changed jobs (23.1%) did. Eleven surgeons who stayed at their first practice (11.3%) indicated a perceived lack of opportunity for career progression while 6 (46.2%) of those who changed jobs had felt this way (p < 0.001). When this question was broken down to specifically assess the effects of the hospital administration and their degree of support for pediatric surgery endeavors, there did not appear to be a statistically significant difference of opinion between those who maintained their first job and those who changed jobs (p = 0.935).

Aspirations of teaching and research also appeared to be related to the desire to change jobs (p = 0.013). Among surgeons who stayed at their first job, 2 (2.1%) stated that they no longer desired to work at an academic or teaching facility, 12 (12.4%) indicated their career goals had changed since beginning their job, 69 (71.1%) that their career goals had not changed, and 7 (7.2%) that their research interests had changed. Among job changers, 2 (15.3%) stated that they had no longer desired to work at an academic or teaching facility, 1 (7.7%) had no longer wished to work in private practice, 2 (15.4%) that career goals had changed after beginning their job, 7 (53.8%) that career goals had not changed since the beginning of their job, and 1 (7.7%) indicated that research interests changed after beginning the job. Surgeons from both groups had differing opinions on their career fulfillment. Among those who stayed at their first job, 22 (22.7%) felt that their careers were not fulfilled while 68 (70.1%) felt fulfilled. For those who changed jobs, 8 (61.5%) alluded to a previous lack of career fulfillment, and 4 (30.8%) had been fulfilled (p = 0.011). Evolving career interests and opportunities for research investigation did not appear to be significant factors in influencing job change (p = 0.335).

Finally, the opportunity to renew contract or become partner was not offered to 3 (3.1%) surgeons who did not change jobs. Therefore, these individuals will likely be leaving their current employment in the near future. 87 (89.7%) surgeons who did not change jobs were afforded this opportunity. All responding surgeons who changed jobs were offered renewal or partnership at their original place of employment (p = 0.813).

3. Discussion

Pediatric surgeons represent a relatively small fraction of board certified surgeons. The competitive nature of fellowship training and demanding lifestyle of the career could be thought to self-select for a certain type of individual. In fact, pediatric surgery applicants have been shown to possess personality traits which differ from their fellow surgeons. Pediatric surgeons tend to score higher in agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability [7].

What then would drive one of these individuals to change jobs? Any particular surgeon’s decision to change jobs is a culmination of numerous factors which would be impossible to fully quantify. We discovered that the number of individuals who changed jobs within the study period was about 12%. In addition, there were specific traits within positions of employment that led to job dissatisfaction and changing jobs early in one’s career. These included (1) a perceived lack of opportunity for career advancement, (2) no longer desiring to work at an academic or teaching facility, (3) excessive case load, (4) personal conflict with partners or staff, (5) career goals unfulfilled by practice, (6) lack of mentorship in partners, and (7) desire to relocate to job closer to the surgeon’s or their spouse’s family.

One question surrounded perception of opportunity at the current or previous place of employment. A far higher proportion of respondents who changed jobs answered that they had a perceived lack of opportunity for career progression at their initial practice. After spending so many years ascending a rigorous surgical hierarchy, it is perhaps not surprising that being immediately limited in career progression would be a severe deterrent. This finding is supported by the later true–false question indicating lack of fulfillment of personal career goals was associated with changing jobs. Interestingly, there was no difference found between groups for whether surgeons were or were not offered employment renewal opportunities or partnership. However, it is possible that surgeons who were not offered such an opportunity underreported this fact.

One statistically significant question involved changing career goals, research interests, and academic or private practice settings. The variable with the largest proportional change was a surgeon’s desire to work at an academic or teaching facility. While most new pediatric surgeons would have spent the majority of their career at academic facilities for training, departmental hierarchy, lower compensation, research obligations, and mandates for trainee instruction could be viewed as very polarizing factors.

Two other questions with statistically significant differences addressed personal conflict with partners or staff and lack of mentor-ship. Of note, these questions were the only two which touched on the importance of interpersonal relationships in the work environment, indicating that interactions with coworkers and superiors are integral to job satisfaction. An astonishingly large proportion of the total respondents (24.5%) reported some form of conflict within their work environment. Although the etiology of these conflicts is unclear, enhancing problem solving and conflict resolution strategies could prove to be an effective way to reduce turnover among practices. Our data support previous research which has suggested that camaraderie correlates highly with job satisfaction [6].

With so much recent attention paid to the importance of lifestyle in medical training and employment, it was initially assumed that related factors might influence employment decisions. Not surprisingly, in a true–false question, an association was found between excessive case load and changing jobs. Indeed other studies have also suggested that increased physician workload decreases the likelihood of satisfaction [8]. A study of rural primary care physicians found workload satisfaction to be a key factor in retaining physicians in a practice [9]. However, in our study, no differences existed surrounding topics of location amenities or work–life balance. Both lighter work load and strong mentorship may be favorable for graduating surgeons who are less prepared for practice, but the preparedness of graduating fellows is far beyond the scope of this paper.

Surgeons who changed jobs were found to more often desire relocation closer to their or their spouse’s family. Not only does this permit increased interaction with family members, but it can be vital for surgeons who need assistance with child or family care. A strong national trend toward two-career families makes this all the more important.

Pediatric surgeons are often nearly a decade beyond completing their medical education and it might be expected that compensation would be paramount for repaying student debt. However, the survey question focusing on how salary compared to the national average was not found to have a statistically significant difference.

Although the scope and design of this study were too superficial to thoroughly investigate the behavioral decision making processes involved in changing jobs, the results do offer a starting place for identifying some of the influential factors. It stands to reason that these factors could be common to other surgical and medical subspecialties as well. Given the scale of factors involved and the small volume of publications addressing them, significant room remains for further research.

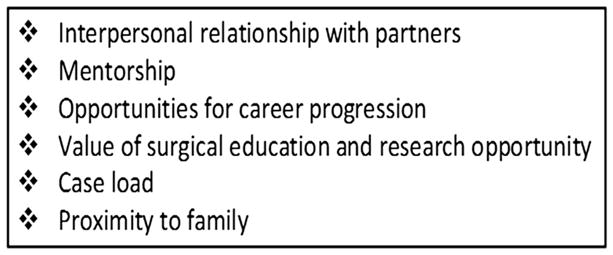

Knowledge of these factors could not only assist prospective pediatric surgeons in their choice of employment, but could help hiring practices identify areas to improve upon that could decrease early job turnover. Candidates can use the identified factors to help prioritize what aspects of a potential job might be most important for career satisfaction (Fig. 2). Identifying a well-structured practice which allows for reasonable caseloads, opportunity for career progression, and goal achievement is paramount. Additionally, this study emphasizes the importance of a workplace environment which fosters mentorship and positive interactions between staff. Finally, it behooves candidates to be self-aware regarding less malleable characteristics such as proximity to family members and the desire to work at an academic or teaching facility.

Fig. 2.

Important factors in job selection for graduating pediatric surgery fellows. Statistically significant factors associated with job changing were listed as considerations.

4. Limitations

There are aspects of the survey’s design which could be viewed as potential weaknesses. The most apparent is the lack of survey validation and the relative paucity of variables addressed in survey questions as compared to how many factors contribute to an individual’s decision to change jobs. However, designers of the project were limited in creating a survey which would appropriately isolate a group of potential key factors, while also being brief and reasonable enough to complete. The survey also did not request participants to quantify how much any one factor influenced their career decision relative to another. Again, it was thought that such a survey would be too lengthy and tedious for respondents, and would result in a lower response rate.

Another potential limitation could be the small study group to which the survey was dispersed. Targeting APSA members specifically allowed for a standardized, facile way of distributing the survey. However, by designating the 222 APSA members to receive the survey, those surgeons who were not members of the organization were excluded. Given the total number of surgeons who likely completed training in the defined time period, roughly 20–80 surgeons were not able to be queried. Passing both the general surgery and pediatric surgery boards is a requirement for APSA membership, so this may have excluded some new surgeons who were not offered contract renewal or partnership.

Distributing the survey only to those who finished training within the past five years accomplished two additional goals of study design. First, this window was thought to encompass the time that early surgeons would likely choose to stay at their first place of employment or change jobs. Additionally, it served as an attempt to limit potentially different factors which might be specific to surgeons changing jobs at a later stage in their career, such as promotion. However, in choosing surgeons who completed training between 2011 and 2016, an inherent limitation was created with regard to the initial survey question. Participants who graduated more recently have had less time, and would be seemingly less likely, to act on the possibility of changing jobs than their predecessors, which could potentially underestimate the number of pediatric surgeons who change jobs soon after fellowship. Information about the quality, stability, and desirability of each surgeons’ first places of employment was also not collected, as this would have lengthened the survey expectantly.

Future investigations could address whether work load burden is perceived to be detrimental to childcare or family obligations. Conflict among partners also seemed to be a common issue which deserves further evaluation as it pertains to surgeon satisfaction. Finally, survey data could be collected from employers of new pediatric surgery graduates to obtain a more comprehensive perspective on the subject.

5. Conclusions

Prior to the survey’s design, it was obvious that early job transition, or perhaps more broadly, job satisfaction, was an incredibly multifactorial concept. Although it was difficult to effectively quantify job satisfaction, we discovered that there were seven key areas that tended to differ statistically with regard to the job change outcome. Some of these variables were related to the structure of the surgeon’s practice environment, such as the desire to work at an academic or teaching facility, as well as excessive case load. Others may represent a failure of the job to meet certain professed expectations, including a perceived lack of opportunities, career goals not being fulfilled, and lack of mentorship. Finally, interpersonal factors, such as personal conflict with partners or staff and a desire to relocate to a job closer to family seemed to play a role in early job transition.

Finding the right job for individuals can often be somewhat stressful. Understanding the factors that result in early employment changes can help prospective job seekers and advisors guide individuals to the most satisfying jobs, with the hopes of allowing them to have the most success and most satisfaction within their first employment position.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.04.028.

References

- 1.Ricketts TC, Adamson WT, Fraher EP, et al. Future supply of pediatric surgeons: analytical study of the current and projected supply of pediatric surgeons in the context of a rapidly changing process for specialty and subspecialty training. Ann Surg. 2017;265(3):609–15. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geiger JD, Drongowski RA, Coran AG. The market for pediatric surgeons: an updated survey of recent graduates. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(3):397–405. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50068. discussion 397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt ML. Sustaining a career in surgery. Am J Surg. 2017;214(4):707–14. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulcrano M, Evans SR, Sosin M. Quality of life and burnout rates across surgical specialties: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(10):970–8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stolar CJ, Aspelund G. First employment characteristics for the 2011 pediatric surgery fellowship graduates. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(1):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson TN, Pearcy CP, Khorgami Z, et al. The physician attrition crisis: a cross-sectional survey of the risk factors for reduced job satisfaction among US surgeons. World J Surg. 2018;42(5):1285–92. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazboun R, Rodriguez S, Thirumoorthi A, et al. Personality traits within a pediatric surgery fellowship applicant pool. J Surg Res. 2017;218:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waddimba AC, Scribani M, Krupa N, et al. Frequency of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with practice among rural-based, group-employed physicians and non-physician practitioners. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):613–28. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1777-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mainous AG, III, Ramsbottom-Lucier M, Rich EC. The role of clinical workload and satisfaction with workload in rural primary care physician retention. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(9):787–92. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.