Abstract

Evaluation of intrathoracic pressure is the cornerstone of the understanding of heart-lung interactions, but is not easily feasible at the bedside. Esophageal pressure (Pes) has been shown to be a good surrogate for intrathoracic pressure and can be more easily measured using a small esophageal catheter, but is not routinely employed. It can provide crucial information for the study of heart-lung interactions in both controlled and spontaneous ventilation. This review presents the physiological basis, the technical aspects and the value in clinical practice of the measurement of Pes.

Keywords: Heart-lung interactions, esophageal pressure, pulsus paradoxus, reverse pulsus paradoxus

Since the first description of heart-lung interactions by Stephen Hales in 1733 (1), the evaluation of the intrathoracic/pleural pressure at the bedside has always been an issue. Esophageal pressure (Pes) has been shown to be a good surrogate of pleural pressure, since its variations are similar despite small differences in absolute values (2-4). Thus, Pes has been considered as a major parameter in the evaluation of heart-lung interactions, but is scarcely used in daily practice for numerous reasons, including technical issues and difficulties in interpretation.

This article aims to show why and how Pes should be measured in interpreting heart-lung interactions. After physiological reminders about the concept of transmural pressure, we will describe the technical aspects and issues of Pes measurement and its interest in two different types of clinical situations: positive pressure breathing-related heart-lung interactions on the one hand, and negative pressure breathing-related heart-lung interactions on the other.

The transmural pressure: back to physiology and definitions

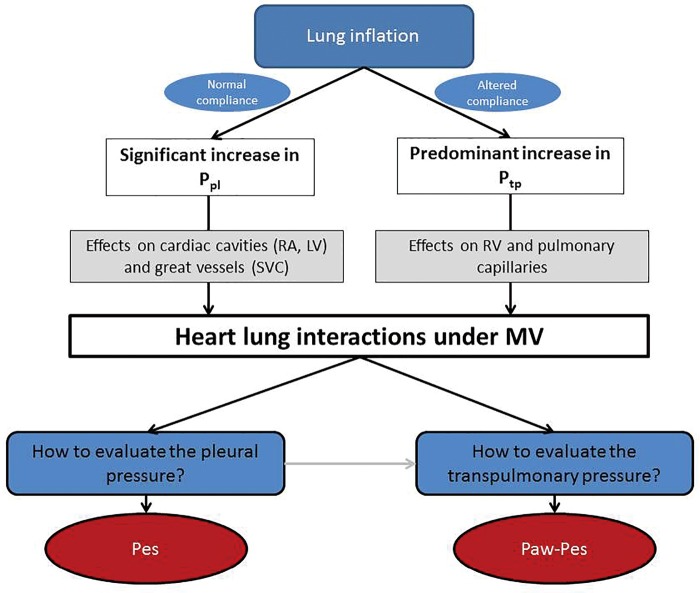

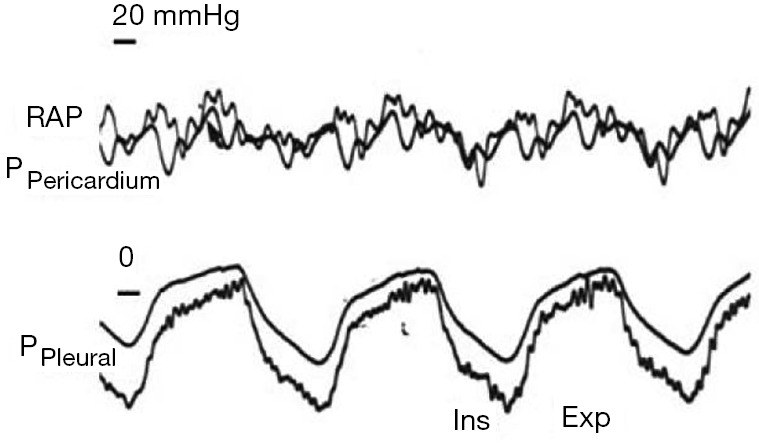

Heart-lung interactions can be defined as the effects of pressure variations of the respiratory system on the circulatory system. Two mains pressures are responsible for such effects: pleural pressure per se and transpulmonary pressure (Ptp). The transmural pressure of a cavity is defined as the pressure measured inside minus the surrounding pressure. The transmural pressure then represents the distending pressure of the cavity and can be considered as a surrogate of its volume. The surrounding pressure of the heart is the pleural pressure, approximated by Pes, except when the pericardial pressure is significantly increased (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Right atrial transmural pressure during cardiac tamponade. During cardiac tamponade, the pressure surrounding the right atrium is no more the pleural pressure, but the pericardial pressure. While the pleural pressure, i.e., Pes, remains low, the pericardial pressure increases and the RAPtm, i.e., RAP minus pericardial pressure, falls, meaning that the right atrial volume is very low. Exp, expiration; Ins, inspiration; Pes, esophageal pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; RAP, right atrial transmural pressure.

In the lungs

Ptp can be defined as the pressure that counteracts all the inward-acting tissue forces distributed at the pleural surface. Ptp can be calculated by subtracting pleural pressure (Ppl) from alveolar pressure (Paw) (5). It reflects the mechanical properties of the lungs and may be relevant in the management of intensive care unit (ICU) patients with increased elastance of the respiratory system. In particular, Ptp could help to overcome the great heterogeneity of ICU patients suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Indeed, the transmission of Paw to the thoracic cavity varies as a function of the relative contribution of chest wall elastance to the total elastance of the respiratory system (Ers) (6). Ppl can thus be estimated using the following formula: ΔPpl = ΔPaw × (EL/Ers), where EL defines lung elastance (7). In normal conditions, chest wall and lung elastances are similar and Ppl and Ptp contribute equally to Paw. Conversely, the more EL is increased, the less Ppl contributes to Paw. In ARDS patients, Jardin et al. demonstrated that Ppl contributed 37% and 24% of Paw in patients with respiratory compliance greater than 45 mL/cmH2O (and a normal lung elastance) or less than 30 mL/cmH2O (and a significantly increased lung elastance), respectively (8). For the same plateau pressure, Ptp may differ greatly according to EL and ECW: some patients will then be exposed to the consequences of a large increase in Ppl, while others will be exposed to the consequences of an increase in Ptp (see part III) (9).

In the cardiac chambers and the great vessels

Right atrial transmural pressure (RAPTM) is defined by the intravascular RAP, measured invasively by a pulmonary artery catheter or a central venous line, minus the surrounding pressure of the atrium. The latter can be approximated by the measurement of pericardial pressure (10). In the absence of pericardial effusion, which is responsible for significant increase in pericardial pressure (11,12), the difference between pleural and pericardial pressure is low and well correlated with Pes (13). RAPTM differs from intravascular RAP since an increase in the latter will decrease venous return according to Guyton’s law (14,15), while an increase of the former will increase cardiac output according to the Frank-Starling law (16,17). Then, except when the chest is opened, as reported by Guyton in his landmark study (18), the venous return to the intravascular RAP curve and the cardiac output to the RAPTM cannot be superimposed, as frequently proposed.

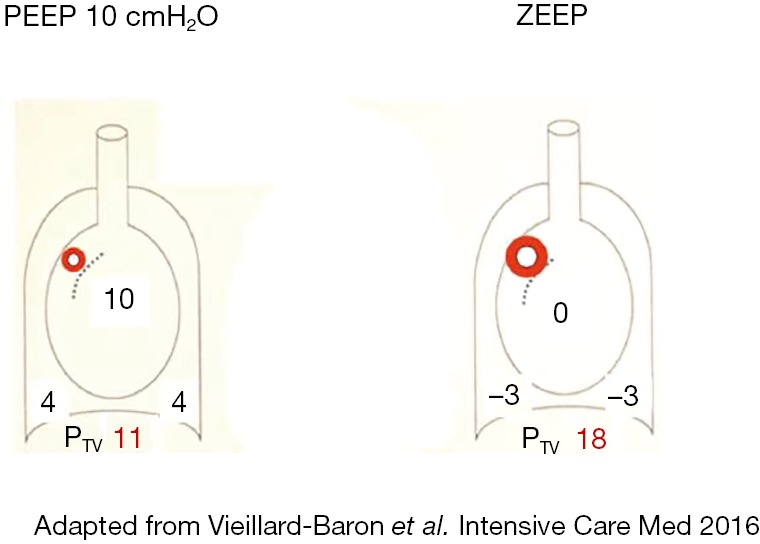

At the interstitial level, the impact of Ppl modification can also be very marked. Indeed, the transvascular pressure, i.e., luminal microvascular pressure minus interstitial pressure assumed to be equivalent to pleural pressure, can differ greatly between controlled breathing and spontaneously breathing patients. In the case of spontaneous breathing, the negative pleural pressure generated by the forceful inspiratory effort can be responsible for very high fluid-filtering transvascular pressure, which could enhance the pulmonary edema of such patients (19,20). This was one of the mechanisms proposed to promote ventilator-induced lung injury and was called lung interdependence (21). Applying a positive (or less negative) pleural pressure by means of application of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) could in part explain the protective effect of PEEP on the generation of pulmonary edema (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of PEEP on transvascular pressure [adapted from (19)]. The left panel represents the example of a mechanically ventilated ARDS patient with 10 cmH2O PEEP. Assuming that the transmission of PEEP to the pleural/interstitial pressure is about one-third, the pleural pressure measured by Pes is 4 cmH2O and the transvascular pressure 11 cmH2O for an intravascular pressure of 15 mmHg. In contrast, ventilated in ZEEP conditions, this patient would have a Pes of −3 cmH2O and then an increase in the transvascular pressure to 18 cmH2O for the same intravascular pressure, exposing him to the risk of pulmonary edema by fluid leakage. PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; Pes, esophageal pressure; Ptv, transvascular pressure.

Pes in usual practice

The first measurement of Pes in healthy humans goes back to the end of the 19th century (22) and the first measurement of Ppl was made in 1900 (23), whereas the classic monograph on Pes dates from 1949 and describes the insertion of a balloon into the esophagus (2). Initially based on a large inflation of the balloon, the method of measuring Pes was improved during the second part of the twentieth century. The most recent advances in the field were the modification of the amount of gas used to inflate the balloon (24,25) and the evaluation of the impact of the position of the balloon in the esophagus (26).

How to measure Pes in 2018

The first generation of custom-made esophageal balloons was exclusively used for experimental research. Such devices have been replaced by second-generation air- or liquid-filled (mainly in neonates) balloons, developed for bedside clinical use thanks to the connection to different monitoring devices (7). Each type of esophageal balloon has technical properties according to its composition, diameter, or length, but usually requires the injection of 0.5 to 4 mL of gas (27). The longer and the more compliant the balloon, the more accurate the measurement of Ppl (28). Some devices are equipped with two balloons for measurement of both esophageal and gastric pressures. New devices are incorporated in naso- or orogastric tubes and allow continuous measurements for a long period (29).

After placing the patient in a semirecumbent position and deflating the esophageal balloon, the catheter is transorally or transnasally introduced in the upper esophagus and then pushed into the stomach. It should be noted that the semirecumbent position should be preferred to the supine position, because in the latter Pes is more altered by cardiac artifacts (30) and also tends to overestimate the value of Pes (26). Once in a gastric position, the balloon is inflated according to the recommendations and the distal part of the catheter is connected to the pressure transducer of a specific device or the ventilator. The gastric position of the balloon can be easily verified by the presence of a positive pressure deflection during a manual epigastric compression (7). The balloon is then progressively withdrawn into the lower two-thirds of the intrathoracic esophagus to obtain the most accurate values (25,30). In spontaneously breathing patients, a Mueller maneuver (inspiration with a closed glottis) can be used to verify that inspiratory effort-generated change in Pes is equal to the change in mouth pressure, in what is called the Baydur test (30). In controlled breathing patients, an external compression of the rib cage can be applied during an expiratory pause to observe a concomitant shift of the Paw and the Pes (28).

What are the limits?

Due to the esophagus wall elastance, the filling volume can be responsible for an overestimation of Pes, even if the balloon is partially inflated (31). In contrast, it has been suggested that Pes could be underestimated if the balloon is unfilled (25,27,32). This might suggest that only respiratory-related changes of Pes (and note absolute values) should be studied with such methods (33). Recently, Mojoli et al. have suggested determining the best filling volume using the volume providing the maximum difference between end-inspiratory and end-expiratory Pes (i.e., maximizing ΔPes) (34). The best filling volume was higher than the factory-recommended inflating volume and was then associated with a significant esophageal wall pressure. A simple calibration procedure defined by PesCAL = Pes − Pew (where Pew defines the pressure generated by the esophageal wall and is calculated according to the esophageal elastance described in human beings), allowed improvement of the assessment of both relative changes and absolute values of Pes (34).

Each commercially available balloon catheter system has its own properties (material, compliance, recommended filling volume…), which exposes Pes measurements to the risk of artifacts. Users of such devices should be aware of the limitations of the corresponding balloon catheter system (35).

The use of Pes for heart-lung interaction evaluation and hemodynamic monitoring

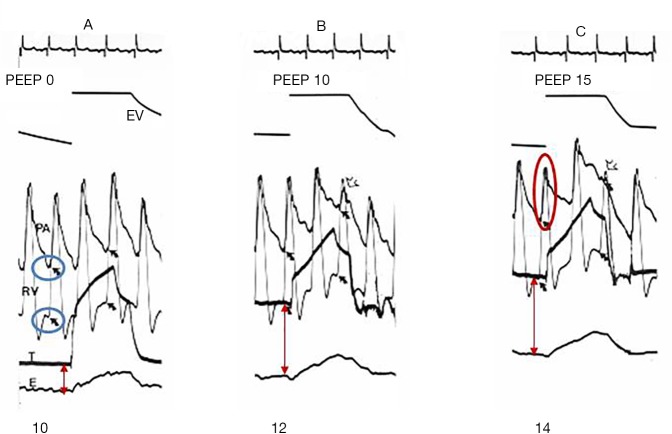

As already said, heart-lung interactions rely on the pleural and transpulmonary pressures, while their evaluation in usual practice by Pes measurement is rarely performed. In the last part of this review, we will describe how the use of Pes measurement could yield crucial information for the understanding of cardiorespiratory interactions, leading to very practical information for appropriate patient management. For educational purposes, we will dichotomize the value of Pes for heart-lung interactions into positive pressure ventilation (Figure 3) and spontaneous breathing.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of the involvement of Pes in heart-lung interactions under positive pressure mechanical ventilation. Under mechanical ventilation, the mechanisms of heart-lung interactions can differ greatly in the case of preserved or altered lung compliance. Heart-lung interactions rely on the increase in Ppl and on PTP in patients with preserved or altered compliance, respectively. Paw, airway pressure; LV, left ventricle; MV, mechanical ventilation; Pes, esophageal pressure; Ppl, pleural pressure; PTP, transpulmonary pressure; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; SVC, superior vena cava.

Reversed pulsus paradoxus

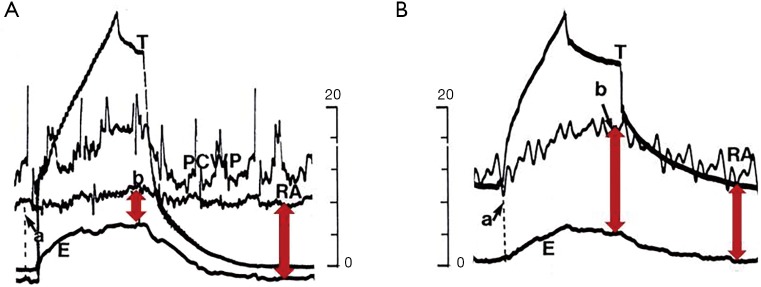

Reversed pulsus paradoxus designates pulse pressure variation during mechanical ventilation (36). It has been described in strict cyclic opposition to the effect of spontaneous breathing on the circulatory system, the inspiration being associated with increased left ventricle (LV) ejection and the expiration with decreased LV ejection. RV and LV stroke volume are 180° out of phase. From an invasive point of view, Pes is mandatory to understand the mechanism of tidal ventilation, either a decrease in RV preload or an increase in RV afterload (Figure 4), while doing an echocardiography permits a simplified approach (19). It is crucial to differentiate patients for whom the main effect of tidal ventilation will be related to increased Ppl (preload effect) from those for whom the main effect of lung inflation will be related to increased Ptp (afterload effect). Indeed, management will be dramatically different. In both mechanisms, intravascular RAP is increased due to the transmission of Ppl to the right atrium. But in the case of a decrease in systemic venous return driven by Ppl, RAPTM is decreased (Figure 4) (37,38), while it is increased in the case of increased RV afterload driven by Ptp (Figure 4). Increased resistance to venous return is a key factor in the decrease in systemic venous pressure driven by Ppl (39). It was suggested to occur at least in the superior vena cava (SVC), using transesophageal echocardiography (40), and was recently demonstrated by Lansdorp et al. in patients after cardiac surgery in whom, by measuring Pes, the authors reported a decrease in the SVC transmural pressure during tidal ventilation (10). A similar observation was made in animals by Berger et al. (41). The pressure transmitted to RAP is probably one of the reasons why RAP is so limited in evaluating RV preload and in predicting the response to fluids, especially in patients with high pericardial pressure, as in cardiac tamponade, or with high Ppl, as observed in the case of high therapeutic PEEP or dynamic hyperinflation. Scharf et al. clearly reported that when a high PEEP was applied in animals, RAP increased dramatically, while RAPTM did not change or even decreased (38). It has been suggested that pulse pressure variation more accurately predicts fluid responsiveness when corrected by changes in Pes (42). In the case of increased RV afterload driven by Ptp, measuring Pes is mandatory when physicians want to invasively determine the effect of a PEEP trial on RV function in ARDS (Figure 5) (43).

Figure 4.

Effects of tidal inflation on right atrial intravascular and transmural pressures. This figure represents the measurements of esophageal pressure (E) and right atrial intravascular pressure (RA) in two different patients under positive pressure ventilation. The transmural pressure of the right atrium defined as esophageal pressure minus RA pressure is materialized by the red arrows. In the first patient (panel A), right atrial transmural pressure decreases during tidal inflation, which illustrates the decrease in venous return due to increased intrathoracic pressure. This effect of tidal inflation is responsible for a fall in right ventricle ejection, leading to a decrease in pulse pressure, named delta-down, because of a preload effect of mechanical ventilation. Conversely, in the second patient (panel B), right atrial transmural pressure increases during tidal inflation, illustrating the systemic congestion secondary to the obstacle to RV ejection. This effect is also responsible for pulse pressure variation (delta-down), but is due to an afterload effect of mechanical ventilation. a, end-expiration; b, end-inspiration. E, esophageal pressure; RA, right atrial intravascular pressure.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of a PEEP trial effect in ARDS using Pes. The left panel (A) represents the PA, RV and esophageal pressures recorded in ZEEP conditions. PTP (red arrow) is low and the RV isovolumetric pressure (between the 2 black arrows), which reflects RV afterload, is 10 cmH2O. In 10 (B) and 15 (C) cmH2O PEEP, PTP increases significantly at end-expiration and is responsible for an increase in RV afterload, attested by an increase in RV isovolumetric pressure to 12 and 14 cmH2O, respectively. Note that the PA pulse pressure (red circle), which reflects the RV stroke volume, decreases with the increase in RV afterload. Blue circles represent closing of the tricuspid valve and opening of the pulmonary valve with the beginning of RV ejection. PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; PA, pulmonary artery; PTP, transpulmonary pressure; RV, right ventricle.

The use of Pes to understand the effect of positive pressure ventilation on the LV is also very important, in particular in patients with severe dilated cardiomyopathy. Indeed, LV afterload may be approached by the LV constraint (σ) expressed as σ = LVPtm × R/t, where LVPtm represents the LV transmural pressure, R the LV radius and t its thickness. In the case of dilated cardiomyopathy, R increases and t decreases, leading to a huge rise in σ. One factor on which physicians may easily act is the LVPtm. It is defined as the intraventricular pressure minus the Ppl evaluated by Pes in the absence of pericardial effusion. Under continuous positive pressure ventilation (CPPV) or intermittent positive pressure ventilation, the increase in Pes is responsible for a fall in LVPtm, and then in LV afterload. However, just looking at the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) induces a dramatic overestimation of LV end-diastolic pressure when PEEP is above 10 cmH2O, reflecting the West zone 1 or 2 condition induced by PEEP (44). In the absence of an esophageal balloon, an elegant method has been proposed to measure transmural PCWP (45). The positive effect of Ppl on LV function has been nicely illustrated by McGregor (46). In a canine model of acute LV failure, Pinsky al. also demonstrated that abdominal and chest wall binding during positive-pressure ventilation was responsible for a significant increase in Pes, which translated into a significant increase in cardiac output secondary to the decrease in LV afterload (47). Finally, it has been experimentally reported that intermittent increased Ppl (10 to 15 mmHg) is a strong determinant of the dUp component (increased LV stroke volume and systolic blood pressure compared with baseline) of blood pressure variations, by inducing a decrease in LV afterload, especially in acute ventricular failure (48).

Pulsus paradoxus

Pronounced respiratory variation in pulse amplitude was first described in 1850 (49) and named nearly 20 years later pulsus paradoxus (50). In 1924, Gauchat and Katz specified that such a rhythmic pulse on palpation of accessible arteries in natural breathing could be encountered in two kinds of patients, those with enhanced intrathoracic pressure variations and those with cardiac tamponade (51). Measurement of Pes could be of a great interest in patients with deep intrathoracic pressure variations.

In acute asthma, pulsus paradoxus reflects deep Ppl variations and was first recognized as a marker of severity (52,53). Actually, measuring Pes is the only way to really understand heart-lung interactions in this situation. Pes varies from a markedly negative level during inspiration (around −25 mmHg) to a positive level during expiration (around 8 mmHg) (54). If Pes is not measured, physicians could consider that RV preload falls during inspiration, as RAP hugely decreases, and becomes negative; in fact, RAPTM increases from 4 to 21 mmHg (54), leading to a completely different interpretation. In this study by Jardin et al., the same observation was made for PCWP (54). These data were confirmed by an echocardiographic study which reported enlargement of the RV at inspiration (55).

In the case of acute airway obstruction, vigorous inspiratory efforts against a totally obstructed upper airway, mimicking a Mueller maneuver, are associated with Ptp and higher transvascular pressure of small interstitial vessels (56,57). Both pulmonary capillary lesion and leakage associated with such conditions are responsible for acute negative-pressure pulmonary edema (58). Very negative Ppl also leads to an increase in systemic venous return to the right heart (59) and then to an overflow into the pulmonary circulation and to an increase in LV afterload as explained above. Managing Pes, if possible, could help to determine the mechanism of such pulmonary edema.

Conclusions

Heart-lung interactions are the effects on the circulatory system of changes in pleural and transpulmonary pressures. In many common clinical situations, such as PEEP application, positive pressure ventilation, acute asthma and cardiac tamponade, the only way to evaluate heart-lung interactions invasively and to determine the mechanism of shock or respiratory failure accurately is to measure Pes. This allows calculation of transmural vascular pressures, which are quite different in these situations from intravascular pressures, and of Ptp, which is a key factor in hemodynamic alterations in ARDS. However, many technical limitations remain when recommending routine Pes measurement at the bedside, even though development of new devices should help physicians to consider it more in the future for evaluation of heart-lung interactions and hemodynamic monitoring. Another approach is to visualize the size of cardiac chambers directly by echocardiography.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hales S. Statical Essays: containing Haemastaticks. London 1733. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buytendijk J. Intraesophageal pressure and lung elasticity. University of Groningen, Groningen 1949; [Thesis]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherniack RM, Farhi LE, Armstrong BW, et al. A comparison of esophageal and intrapleural pressure in man. J Appl Physiol 1955;8:203-11. 10.1152/jappl.1955.8.2.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dornhorst AC, Howard P, Leathart GL. Pulsus paradoxus. Lancet 1952;1:746-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(52)90502-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mead J, Takishima T, Leith D. Stress distribution in lungs: a model of pulmonary elasticity. J Appl Physiol 1970;28:596-608. 10.1152/jappl.1970.28.5.596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Carlesso E, et al. Bench-to-bedside review: chest wall elastance in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Crit Care 2004;8:350-5. 10.1186/cc2854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mauri T, Yoshida T, Bellani G, et al. Esophageal and transpulmonary pressure in the clinical setting: meaning, usefulness and perspectives. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:1360-73. 10.1007/s00134-016-4400-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jardin F, Genevray B, Brun-Ney D, et al. Influence of lung and chest wall compliances on transmission of airway pressure to the pleural space in critically ill patients. Chest 1985;88:653-8. 10.1378/chest.88.5.653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Talmor D, Sarge T, O'Donnell CR, et al. Esophageal and transpulmonary pressures in acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1389-94. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215515.49001.A2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lansdorp B, Hofhuizen C, van Lavieren M, et al. Mechanical ventilation-induced intrathoracic pressure distribution and heart-lung interactions*. Crit Care Med 2014;42:1983-90. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnard H. The functions of the pericardium. J Physiol (Lond) 1898;22:43-8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton DR, Dani RS, Semlacher RA, et al. Right atrial and right ventricular transmural pressures in dogs and humans. Effects of the pericardium. Circulation 1994;90:2492-500. 10.1161/01.CIR.90.5.2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan BC, Guntheroth WG, Dillard DH. Relationship of Pericardial to Pleural Pressure During Quiet Respiration and Cardiac Tamponade. Circ Res 1965;16:493-8. 10.1161/01.RES.16.6.493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyton AC. Determination of cardiac output by equating venous return curves with cardiac response curves. Physiol Rev 1955;35:123-9. 10.1152/physrev.1955.35.1.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyton AC, Lindsey AW, Abernathy B, et al. Venous return at various right atrial pressures and the normal venous return curve. Am J Physiol 1957;189:609-15. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1957.189.3.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank O. Die Grundform des Arteriellen Pulses. Zeitschrift für Biologie 1899;37:483-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starling EH, Visscher MB. The regulation of the energy output of the heart. J Physiol 1927;62:243-61. 10.1113/jphysiol.1927.sp002355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyton AC, Lindsey AW, Kaufmann BN. Effect of mean circulatory filling pressure and other peripheral circulatory factors on cardiac output. Am J Physiol 1955;180:463-8. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1955.180.3.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vieillard-Baron A, Matthay M, Teboul JL, et al. Experts' opinion on management of hemodynamics in ARDS patients: focus on the effects of mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:739-49. 10.1007/s00134-016-4326-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida T, Uchiyama A, Matsuura N, et al. Spontaneous breathing during lung-protective ventilation in an experimental acute lung injury model: high transpulmonary pressure associated with strong spontaneous breathing effort may worsen lung injury. Crit Care Med 2012;40:1578-85. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182451c40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webb HH, Tierney DF. Experimental pulmonary edema due to intermittent positive pressure ventilation with high inflation pressures. Protection by positive end-expiratory pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis 1974;110:556-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luciani L. Delle oscillazioni della pressione intratoracica intrabdominale. Studio sperimentale. Arch Sci Med 1878;2:177-224. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aron E. Der intrapleurale Druck beim Iebenden gesunden Menschen. Arch Puthol Artat Physiol 1900;160:266. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mead J, Mc IM, Selverstone NJ, et al. Measurement of intraesophageal pressure. J Appl Physiol 1955;7:491-5. 10.1152/jappl.1955.7.5.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milic-Emili J, Mead J, Turner JM, et al. Improved Technique for Estimating Pleural Pressure from Esophageal Balloons. J Appl Physiol 1964;19:207-11. 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.2.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milic-Emili J, Mead J, Turner JM. Topography of Esophageal Pressure as a Function of Posture in Man. J Appl Physiol 1964;19:212-6. 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.2.212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mojoli F, Chiumello D, Pozzi M, et al. Esophageal pressure measurements under different conditions of intrathoracic pressure. An in vitro study of second generation balloon catheters. Minerva Anestesiol 2015;81:855-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akoumianaki E, Maggiore SM, Valenza F, et al. The application of esophageal pressure measurement in patients with respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:520-31. 10.1164/rccm.201312-2193CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiumello D, Gallazzi E, Marino A, et al. A validation study of a new nasogastric polyfunctional catheter. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:791-5. 10.1007/s00134-011-2178-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baydur A, Behrakis PK, Zin WA, et al. A simple method for assessing the validity of the esophageal balloon technique. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;126:788-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hedenstierna G, Jarnberg PO, Torsell L, et al. Esophageal elastance in anesthetized humans. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1983;54:1374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petit JM, Milic-Emili G. Measurement of endoesophageal pressure. J Appl Physiol 1958;13:481-5. 10.1152/jappl.1958.13.3.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulati G, Novero A, Loring SH, et al. Pleural pressure and optimal positive end-expiratory pressure based on esophageal pressure versus chest wall elastance: incompatible results*. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1951-7. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a3de5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mojoli F, Iotti GA, Torriglia F, et al. In vivo calibration of esophageal pressure in the mechanically ventilated patient makes measurements reliable. Crit Care 2016;20:98. 10.1186/s13054-016-1278-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walterspacher S, Isaak L, Guttmann J, et al. Assessing respiratory function depends on mechanical characteristics of balloon catheters. Respir Care 2014;59:1345-52. 10.4187/respcare.02974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massumi RA, Mason DT, Vera Z, et al. Reversed pulsus paradoxus. N Engl J Med 1973;289:1272-5. 10.1056/NEJM197312132892403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson D, Stevens RM, Friesinger GC, et al. The effect of the Valsalva maneuver on echocardiographic dimensions in man. Circulation 1977;55:596-62. 10.1161/01.CIR.55.4.596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scharf SM, Caldini P, Ingram RH., Jr Cardiovascular effects of increasing airway pressure in the dog. Am J Physiol 1977;232:H35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nanas S, Magder S. Adaptations of the peripheral circulation to PEEP. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;146:688-93. 10.1164/ajrccm/146.3.688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vieillard-Baron A, Augarde R, Prin S, et al. Influence of superior vena caval zone condition on cyclic changes in right ventricular outflow during respiratory support. Anesthesiology 2001;95:1083-8. 10.1097/00000542-200111000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berger D, Moller PW, Weber A, et al. Effect of PEEP, blood volume, and inspiratory hold maneuvers on venous return. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2016;311:H794-806. 10.1152/ajpheart.00931.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Wei LQ, Li GQ, et al. Pulse Pressure Variation Adjusted by Respiratory Changes in Pleural Pressure, Rather Than by Tidal Volume, Reliably Predicts Fluid Responsiveness in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med 2016;44:342-51. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jardin F, Brun-Ney D, Cazaux P, et al. Relation between transpulmonary pressure and right ventricular isovolumetric pressure change during respiratory support. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1989;16:215-20. 10.1002/ccd.1810160402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jardin F, Farcot JC, Boisante L, et al. Influence of positive end-expiratory pressure on left ventricular performance. N Engl J Med 1981;304:387-92. 10.1056/NEJM198102123040703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teboul JL, Pinsky MR, Mercat A, et al. Estimating cardiac filling pressure in mechanically ventilated patients with hyperinflation. Crit Care Med 2000;28:3631-6. 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGregor M. Current concepts: pulsus paradoxus. N Engl J Med 1979;301:480-2. 10.1056/NEJM197908303010905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinsky MR, Summer WR. Cardiac augmentation by phasic high intrathoracic pressure support in man. Chest 1983;84:370-5. 10.1378/chest.84.4.370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pizov R, Ya'ari Y, Perel A. The arterial pressure waveform during acute ventricular failure and synchronized external chest compression. Anesth Analg 1989;68:150-6. 10.1213/00000539-198902000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams C. Organic diseases of the heart. Part 2. London J Med 1850;2:460-73. 10.1136/bmj.s2-2.17.460 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kussmaul A. Uber schwielige mediastino-pericarditis und den paradoxen puls. Berl Kin Wochenschr 1873;10:461-64. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gauchat H, Katz L. Observations on pulsus paradoxus (with special reference to pericardial effusions. Arch Intern Med 1924;33:350-70. 10.1001/archinte.1924.00110270071008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knowles GK, Clark TJ. Pulsus paradoxus as a valuable sign indicating severity of asthma. Lancet 1973;2:1356-9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(73)93324-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rebuck AS, Read J. Assessment and management of severe asthma. Am J Med 1971;51:788-98. 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90307-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jardin F, Farcot JC, Boisante L, et al. Mechanism of paradoxic pulse in bronchial asthma. Circulation 1982;66:887-94. 10.1161/01.CIR.66.4.887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jardin F, Dubourg O, Margairaz A, et al. Inspiratory impairment in right ventricular performance during acute asthma. Chest 1987;92:789-95. 10.1378/chest.92.5.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koh MS, Hsu AA, Eng P. Negative pressure pulmonary oedema in the medical intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1601-4. 10.1007/s00134-003-1896-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oswalt CE, Gates GA, Holmstrom MG. Pulmonary edema as a complication of acute airway obstruction. Jama 1977;238:1833-5. 10.1001/jama.1977.03280180037022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhattacharya M, Kallet RH, Ware LB, et al. Negative-Pressure Pulmonary Edema. Chest 2016;150:927-33. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kollef MH, Pluss J. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema following upper airway obstruction. 7 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1991;70:91-8. 10.1097/00005792-199103000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]