Abstract

Introduction: While fever is the main complaint among pediatric emergency services and high antibiotic prescription are observed, only a few studies have been published addressing this subject. Therefore this systematic review aims to summarize antibiotic prescriptions in febrile children at the ED and assess its determinants.

Methods: We extracted studies published from 2000 to 2017 on antibiotic use in febrile children at the ED from different databases. Author, year, and country of publishing, study design, inclusion criteria, primary outcome, age, and number of children included in the study was extracted. To compare the risk-of-bias all articles were assessed using the MINORS criteria. For the final quality assessment we additionally used the sample size and the primary outcome.

Results: We included 26 studies reporting on antibiotic prescription and 28 intervention studies on the effect on antibiotic prescription. In all 54 studies antibiotic prescriptions in the ED varied from 15 to 90.5%, pending on study populations and diagnosis. Respiratory tract infections were mostly studied. Pediatric emergency physicians prescribed significantly less antibiotics then general emergency physicians. Most frequent reported interventions to reduce antibiotics are delayed antibiotic prescription in acute otitis media, viral testing and guidelines.

Conclusion: Evidence on antibiotic prescriptions in children with fever presenting to the ED remains inconclusive. Delayed antibiotic prescription in acute otitis media and guidelines for fever and respiratory infections can effectively reduce antibiotic prescription in the ED. The large heterogeneity of type of studies and included populations limits strict conclusions, such a gap in knowledge on the determining factors that influence antibiotic prescription in febrile children presenting to the ED remains.

Keywords: pediatric emergency care, fever, children, antibiotic prescription, management

Introduction

Fever is the main complaint among pediatric emergency services (1). In only 15% (IQR 8·0–23·2%) a serious bacterial infection (SBI) is diagnosed with pneumonia and urinary tract infection (UTI) being the most prevalent (2, 3).

In contrast to the above, high antibiotic prescriptions are observed in febrile children (4, 5). Guidelines, or new diagnostic approaches have shown to effectively reduce antibiotic prescriptions in primary care (6–9). This is important because unnecessary antibiotic use increases antibiotic resistance (10, 11). In contrast to hospital based studies or primary care settings (11–15), few studies have been published in emergency department (ED) settings nor do we have valid estimates of potential benefits of antibiotic reducing interventions. Therefore our primary study aim is to assess antibiotic prescriptions for febrile children visiting the emergency department and their determinants. Secondary, we aim to investigate potential interventions that have been proven to be effective in the ED.

Methods

Study characteristics

All descriptive and interventional studies published in 2000–2017 reporting on antibiotic use in children (age under 18) with fever in the emergency department were eligible for this review.

Search strategy

We searched Embase, Medline (OvidSP), Web-of-science, Scopus, Cinahl, Cochrane, PubMed publisher, and Google scholar for the (analogs of) keywords: fever, antibiotics, emergency department, children and antibiotic prescription. Initially search was performed in 2015 and updated in October 2017 (Supplementary Material 1). References were checked for additional articles to be included.

Inclusion

A screening by title/abstract resulted in potential eligible articles that underwent full text review. Two authors reviewed all articles; any discrepancies were solved by oral agreement between authors.

– Setting: Emergency department; if mixed settings, at least 30% (50 patients minimum) of the population needed to be admitted to the ED.

– Design: observational studies and randomized controlled trials with a minimum of 50 participants.

– Outcome: the studies had to report the number or percentage of antibiotics prescribed.

– Population: participants under the age of 18; if mixed ages, at least 20% of the population needed to be <18 years (with a minimum of 50) or age specific antibiotic prescriptions had to be presented. Studies on children with specific comorbidities only were excluded.

– Fever: at least 30% of all included children needed to have fever or the reason of visit was (reported) fever.

Quality assessment of included articles

To compare the risk-of-bias of all these different study designs all articles were assessed using the MINORS criteria (16). Zero points were given for the item if not reported, one point if reported but insufficient and two points if reported and sufficient. As loss to follow-up was not applicable, due to emergency setting, we have let this particular item out of consideration; the maximum score for studies is 14 or 22 for respectively non-comparative and comparative studies. A maximum score on the MINORS criteria was needed to receive the status of a low risk of bias study (A) (17). For the final quality assessment we additionally used the sample size and the primary outcome. A high quality study was defined by status low risk of bias (A) on the MINORS, antibiotic prescription being the primary outcome and a sample size of at least 500 children. Two reviewers (EV and RO) have independently assessed all included studies. Supplementary Material 2 contains the complete quality assessment.

Data extraction and analysis

Extracted data included: Author, year, and country of publishing, study design, inclusion criteria, primary outcome, median (or mean when median not available) age, number of included children. Aiming to invest determinants of antibiotic prescription, we additionally extracted (if available): diagnosis, type of antibiotics, type of physicians, and type of intervention.

Due to heterogeneity in participants, outcome measures, interventions and study designs, no statistical pooling but a qualitative analysis was performed (18). Results are presented for the 5 main diagnosis, i.e., fever, AOM, pneumonia, other respiratory tract infections (RTI other) and UTI, with a minimum of 50 cases per diagnostic group required.

Results

Literature search

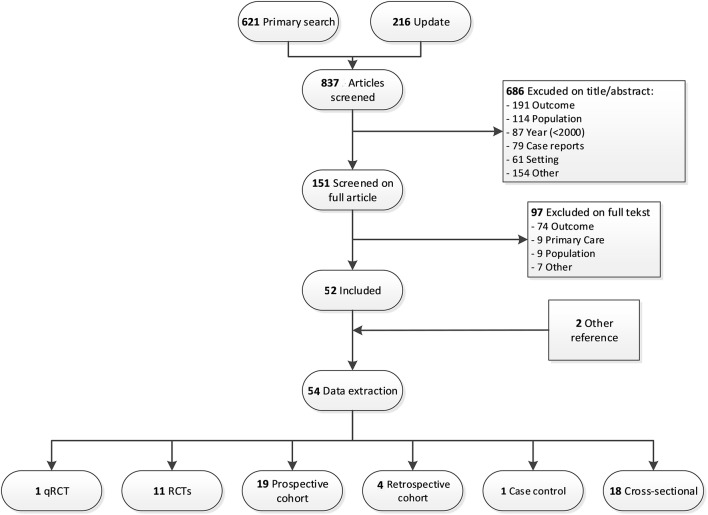

We obtained 837 articles by literature search. Screening the full text articles excluded 97 out of 151, which leaves 52 articles for data extraction. Two additional studies were included by reference check of included studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection and exclusion.

Characteristics of the included studies

The study characteristics are presented in Table 1 for the included 54 studies. Most studies come from the US (n = 32, 59%), 16 others came from Europe, and 6 others from Canada (n = 3) (33, 36, 49), Australia (n = 2) (3), and Israel (n = 1) (26). The size of the studied population varied between 72 and 266.000 participants (median = 391). Most studies included children up to 36 months (n = 14, 25%) or all ages < 18 year (n = 18, 32%). Antibiotic prescription was the primary outcome in 33 studies (59%). Quality and feasibility assessment of the included studies (Supplementary Material 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of descriptive studies about antibiotic prescription.

| Reference, Country | Study design | Age group/inclusion | Median (IQR) or Mean age ± SD | Inclusion criteria | N children included | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. (19), US | CSp | 0–18 years | NR | URTI | 321 | Low |

| Angoulvant et al. (20), France | CR | <18 years | 17 months (7–40) | ARTI | 53.055 | High |

| Aronson et al. (21), US | CSr | 29–56 days | 46 days (37–53) | Fever | 1626 | High |

| 45 days (37–53) | ||||||

| Ayanruoh et al. (22), US | CSr | 3–18 years | NR | Clinical diagnosis of pharyngitis | 8280 | Low |

| Benin et al. (23), US | CSr | 3–18 years | 8.7 years (6–13) | Diagnosis pharyngitis | 391 | Moderate |

| Benito-Fernández et al. (24), Spain | CP | 0–36 months | 6.86 months ± 6.3° | Fever without source | 206 | Low |

| 6.55 months ± 6.8° | ||||||

| Blaschke et al. (25) US◇ | CSr | All ages | 53% < 18 years | Influenza | 58 | Low |

| Brauner et al. (26), Israel | CCr | 3–36 months | NR | Fever and complete blood count | 292 | Moderate |

| Bonner et al. (27), US | RCT | 2 months−21 years | NR | Influenza | 202 | Moderate |

| Bustinduy et al. (28), UK | CP | <16 years | 2 years (1–4 years) | Fever or reported fever | 1097 | Moderate |

| Chao et al. (29), US | RCT | 2–12 years | 5.01 years (3.67–6.68) | AOM | 206 | Moderate |

| 3.73 years (2.82–5.75) | ||||||

| Craig et al. (3), Australia | CP | <6 years | ± 60% < 24 months | Fever | 15.781 | High |

| Coco et al. (30), US | CSr | <12 years | ± 2 years* | AOM | 8325 | High |

| Colvin et al. (31), US | CP | 2–36 months | 8.0 months | Fever without source ¥ | 75 | Low |

| Copp et al. (32), US | CSr | <18 years | ±6 years* | UTI | 1828 (36% in ED) | Low |

| Doan et al. (33), Canada | RCT | 3–36 months | 15 months (3–36) | Acue respiratory symptoms | 199 | Moderate |

| 14 months (4–34) | ||||||

| Fischer et al. (34), US | CP | 2–18 years | 68% 2–6 years | AOM | 144 | Low |

| Galetto Lacour et al. (35), Switzerland | CP | 7 days −36 months | 11 months* | Fever without source ¥ | 124 | Moderate |

| Galetto-Lacour et al. (35), Switzerland | CP | 7 days −36 months | 7.2 months (0.4–31.1) | Fever without source ¥ | 99 | Low |

| 9.7 months (0.7–34) | ||||||

| Goldman et al. (36), Canada | CP | <3 months | 48.7 days ± 23.6° | Fever | 257 | Low |

| Houten et al. (37), Netherlands | CP | 2–60 months | 21 months ± 16° | Fever and LRTI symptoms or without source | 577 | Moderate |

| Irwin et al. (38), UK | CP | <16 years | 2.4 years (0.9–5.7) | Fever and blood tests | 1101 | High |

| Isaacman et al. (39), US | CR | 3–36 months | 18 months ± 9.8° | Fever without source in a GED¥ | 79 | Low |

| 16.3 months ±8.8° | Fever without source in a PED¥ | 498 | ||||

| Iyer et al. (40), US | RCT | 2–24 months | ±75% 6–24 months | Fever | 700 | Moderate |

| Jain et al. (41), US | CP | <18 years | NR | Fever | 19075 | High |

| Khine et al. (42), US | CR | 3–36 months | 15.2 months ±8.7° | Reported fever in GED | 237 | Moderate |

| 3–36 months | 16.6 months ±9.1° | Reported fever in PED | 224 | |||

| Kilic et al. (43) Turkey | CSr | 3–140 months | 41.2 months ±31° | Asthma, croup, Bronchiolitis | 2544 | Low |

| Kornblith et al. (44), US | CSr | 0–18 years | ± 56% 1–5 years | ARTI | 6461 | High |

| Kronman et al. (45), US | CSr | 1–18 years | 50–60% 1–5 years | CAP | 266.000 | High |

| Lacroix et al. (46), France | RCT | 7 days−36 months | 3.4 months (1.5–10.4) | Fever without source | 271 | High |

| 4.8 months (1.7–10.4) | ||||||

| Linder et al. (47), US | CSr | 3–17 years | 45% 6–11 years | Sore throat | 6955 | High |

| Li-Kim-Moy et al. (48), Australia | CR | 0 ≤ 18 years | 3.1 years (1.1–7.4) | Lab proven influenza | 301 | Moderate |

| Manzano et al. (49), Canada | RCT | 1–36 months | 12 ± 8 months° | Fever | 384 | High |

| 12 ± 8 months° | ||||||

| Massin et al. (50) Belgium | CP | 1–36 months | 13.8 months ±9.7° | Fever without source ¥ | 376 | Moderate |

| McCaig et al. (51), US | CSr | 3 months−2 years | NR | Fever and BC (discharged) | 5.4% of all ED visits | Low |

| McCormick et al. (52), US | RCT | 6–72 months | ±60% < 1 years | AOM | 209 | Moderate |

| Murray et al. (53), US | CP | <56 days | 36 days ± 13.8 | Fever | 520 | Low |

| Nelson et al. (54), US* | CP | 3 months−18 years | 2.8 years (4.4) | Pneumonia | 3220 | High |

| Nibhanipudi et al. (55), US* | CP | 2–17 years | 5.72 years ± 0.38° (m) | AOM | 100 | Low |

| 7.41 years ± 0.75° (f) | ||||||

| Ochoa et al. (56), Spain | CSr | 0–18 years | ±3 years (1 months−18 years) | ARTI | 6249 | High |

| Ong et al. (57), US | CP | All ages (20% child) | 33 years | URTI | 272 | Moderate |

| Özkaya et al. (58), Turkey | CSp | 3–14 years | 5.7 years ± 3.4° | Influenza like illness | 97 | Low |

| 4.25 years ± 2.02 | ||||||

| Ouldali et al. (59), France | qRCT | <18 years | 1.6 years (0.7–3.6) | ARTI | 196.062 | High |

| 1.7 years (0.7–3.7) | ||||||

| Planas et al. (60), Spain | CP | <3 months | 35 days ± 31° | Fever without source and BC (admitted) ¥ | 381 | Moderate |

| Ploin et al. (61), France | CP | <36 months | NR | Fever during influenza season | 538 | Moderate |

| Poehling et al. (62), US | RCT | <5 years | NR | Fever or ARS during influenza season | 305 | Moderate |

| Shah et al. (63), US | CSr | 1–18 years | ± 63% 1–4 years | Fever and cough or respiratory distress | 3466 | Moderate |

| Sharma et al. (64), US | CSr | 2–24 months | 9 months ° | Fever and positive influenza test | 72 | Low |

| Spiro et al. (65), US | RCT | 6–35 months | 17.3 months° | Fever or ARS | 681 | High |

| 17.2 months° | ||||||

| Spiro et al. (66), US | RCT | 6 months−12 years | 3.2 years | AOM | 283 | High |

| 3.6 years | ||||||

| Trautner et al. (67), US | CSp | <18 years | 17 months (11–25 months) | Hyperpyrexia | 103 | Moderate |

| de Vos-Kerkhof et al. (68), Netherlands | RCT | 1 months−16 years | 1.7 years (0.8–3.9) | Fever | 439 | Moderate |

| 2.0 years (1.0–4.2) | ||||||

| Waddle and Jhaveri, (69), US | CSr | 3–36 months | 17 months ± 11° | FWS and BC | 423 | Low |

| 15 months ± 10° | ||||||

| Wheeler et al. (70), US | CP | ≤ 18 years | 3 years (1 months−20 years) | Viral infections | 144 | Moderate |

CC, case control; CP, prospective cohort; CR, retrospective cohort; CS, cross-sectional; r, retrospective; p, prospective.

Estimated/calculated from numbers in article.

Mean age is given, median age was not reported.

Fever without source: as defined in corresponding study.

Sixteen studies (29%) were considered as high quality and 17 (30%) were considered low quality. In general, observational studies did not describe sufficiently how sample size was approximated. Almost all high quality studies, except one (3), used antibiotic prescriptions as a primary outcome.

Antibiotic prescriptions in febrile children and specific conditions

Table 2 presents the antibiotic prescriptions among the five diagnostic groups we distinguished. Sixteen out of 26 descriptive studies focused on febrile children in general, one paper specifically addressed acute otitis media (AOM) (30), two pneumonia (45, 63), four other respiratory infections (RTI other)(19, 23, 43, 57), and one urinary tract infections (UTI)(32). One paper on febrile children also provide separate numbers for pneumonia and UTI (3) and one for AOM (61). Two additional papers focused on respiratory infections and provided separate numbers for pneumonia, AOM and RTI other (44, 56).

Table 2.

Antibiotic prescription per diagnosis.

| Reference, Country | Age group/ inclusion | Median (IQR) or Mean age ± SD | Inclusion criteria | N children included | N antibiotics, % of study populationł |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEVER IN GENERAL | |||||

| Bustinduy et al. (28), UK | <16 years | 2 years (1–4 years) | Fever or reported fever | 1097 | 44% |

| Colvin et al. (31), US | 2–36 months | 8.0 months | Fever without source ¥ | 75 | 45% |

| Craig et al. (3), Australia | <6 years | ± 60% < 24 months | Fever | 15.781 | 27% |

| Galetto Lacour et al. (35), Switzerland | 7 days−36 months | 11 months* | Fever without source ¥ | 124 | 62.1% |

| Galetto-Lacour et al. (35), Switzerland | 7 days−36 months | 7.2 months (0.4–31.1) 9.7 months (0.7–34) | Fever without source ¥ | 99 | 71% |

| Goldman et al. (36), Canada | <3 months | 48.7 days ± 23.6° | Fever | 257 | 55% |

| Houten et al. (60), Netherlands | 2–60 months | 21 months ± 16° | Fever and LRTI symptoms or without source | 577 | 39% |

| Isaacman et al. (39), US | 3–36 months | 18 months ± 9.8° | Fever without source in a GED¥ | 79 | 39.2% |

| 16.3 months ±8.8° | Fever without source in a PED¥ | 498 | 16.7% | ||

| Khine et al. (42), US | 3–36 months | 15.2 months ±8.7° | Reported fever in GED | 237 | 41% |

| 3–36 months | 16.6 months ±9.1° | Reported fever in PED | 224 | 27% | |

| Massin et al. (50), Belgium | 1–36 months | 13.8 months ± 9.7° | Fever without source ¥ | 376 | 15% |

| Ploin et al. (61), France | <36 months | NR | Fever during influenza season | 538 | 34.8% |

| FEVER AND SELECTION ON ADDITIONAL TESTING OR CHARACTERISTICS | |||||

| Irwin et al. (38), UK | <16 years | 2.4 years (0.9–5.7) | Fever and blood tests | 1101 | 855, 78% |

| Trautner et al. (67), US | <18 years | 17 months (11–25 months) | Hyperpyrexia | 103 | 46, 61.3% |

| Brauner et al. (26), Israel | 3–36 months | NR | Fever and complete blood count | 292 | 148, 50.7% |

| Planas et al. (60), Spain | <3 months | 35 days ± 31° | Fever without source and BC (admitted) ¥ | 381 | 281, 73.8*% |

| AOM | |||||

| Coco et al. (30), US | <12 years | ± 2 years* | AOM | 8325 | 82.6% |

| Kornblith et al. (44), US | 0–18 years | ± 56% 1–5 years | AOM | 647 | 88% |

| Ochoa et al. (56), Spain | 0–18 years | ±3 years (1 months−18 years) | AOM | 821 | 93% |

| Ploin et al. (61), France | <36 months | NR | Fever during influenza season | 18 | 89% |

| PNEUMONIA | |||||

| Craig et al. (3) Australia | <6 years | ± 60% < 24 months | Pneumonia | 533 | 69% |

| Kornblith et al. (44), US | 0–18 years | ± 56% 1–5 years | Pneumonia | 657 | 86% |

| Kronman et al. (45), US | 1–18 years | 50–60% 1–5 years | CAP | 266.000 | 86.1% |

| Ochoa et al. (56), Spain | 0–18 years | ±3 years (1 months−18 years) | Pneumonia | 288 | 93% |

| Shah et al. (63), US | 1–18 years | ± 63% 1–4 years | Pneumonia | 347 | 82% |

| RTI OTHER | |||||

| Ahmed et al. (19), US | 0–18 years | NR | URTI | 321 | 43% |

| Benin et al. (23), US | 3–18 years | 8.7 years (6–13) | Diagnosis pharyngitis | 391 | 23% |

| Kilic et al. (43), Turkey | 3–140 months | 41.2 months ±31° | Asthma, croup, Bronchiolitis | 2544 | 16.6% |

| Kornblith et al. (44), US | 0–18 years | ± 56% 1–5 years | URTI | 5157 | 36% |

| Ochoa et al. (56), Spain | 0–18 years | ±3 years (1 months−18 years) | URTI | 5140 | 51% |

| Ong et al. (57), US | All ages (20% child) | 33 years | URTI | 272 | 83, 31% |

| UTI | |||||

| Copp et al. (32), US | <18 years | ±6 years* | UTI | 1828 | 70% |

| Craig et al. (3), Australia | <6 years | ± 60% < 24 months | Fever | 543 | 66% |

Estimated/calculated from numbers in article.

Mean age is given, median age was not reported.

Fever without source: as defined in corresponding study.

Antibiotic prescription is given for reported age group, except for Ong et al (57) antibiotic use for all ages is given.

Fever

Sixteen out of 26 studies focused on febrile children in general, seven of them selected children based on fever without source; five included febrile children based on additional testing (Table 2). In studies of general febrile populations only, antibiotic prescriptions ranged from 15 to 71% (3, 31, 35, 36, 39, 42, 50, 61, 71). The lowest prescriptions (15%) came from a study on parenteral empirical antibiotics only (50). Study quality did not influence antibiotic prescription rate.

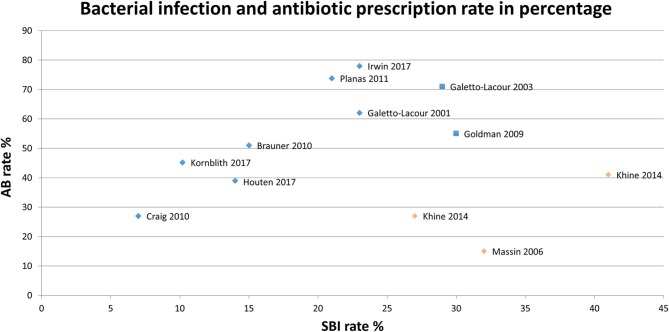

Three high quality, six moderate quality and two low quality studies reported on SBI rate, which ranged from 7 to 41% (Figure 2) (3, 26, 35–38, 42, 44, 50, 60, 71). As the SBI rate in Khine et al. (42) is similar to antibiotic prescriptions, one may question how SBI is defined. Massin et al. (50) reports on parenteral antibiotics only and may not represent antibiotic prescription in total. Focusing on the remaining eight studies, we observe a trend toward higher antibiotic prescriptions with higher rates of SBI, although not significant.

Figure 2.

Serious bacterial infection rate and antibiotic prescriptions per study.  High/Moderate quality,

High/Moderate quality,  High/Moderate quality, outlier,

High/Moderate quality, outlier,  Low quality,

Low quality,  Low quality, outlie.

Low quality, outlie.

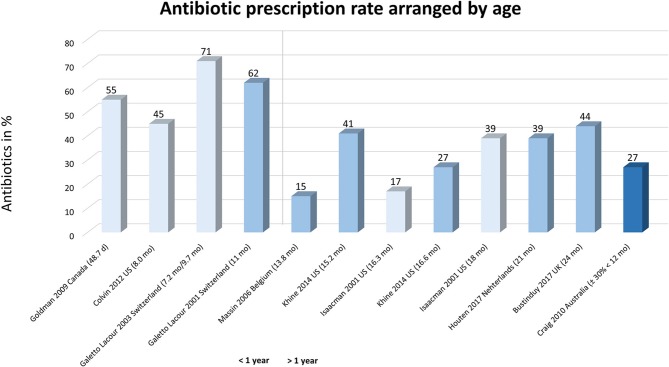

In the studies on fever in general, we observed a higher prescriptions in children under the age of one (45 to 71%; weighted mean 58%), compared to older ones (prescriptions of 17 to 44%; weighted mean 28%), independent of study quality (Figure 3) (3, 28, 31, 35–37, 39, 42, 50, 71).

Figure 3.

Antibiotic prescriptions arranged on age in children with fever. Studies are arranged by age, i.e., left represents younger children to right (older ages). Light bars represent studies with a low quality.

None of the studies on febrile children in general compared antibiotic prescriptions between countries. In the eleven studies (3, 28, 31, 35–37, 39, 42, 50, 61, 71) on children with fever in general (without additional testing), the highest prescriptions were reported in a Swiss study (71%) (35) and the lowest in a study originating from the US (17%) (39). The three studies originating from the US reported antibiotic prescription between 39–45% (31, 39, 42); for the two Swiss studies this varied from 62 to 71%, although originating from the same hospital (35, 71).

Antibiotic prescription for specific diagnoses

Four studies provided data for antibiotic prescription in AOM, ranging from 88–93%. We could not determine influences of age on prescriptions. Five studies reported on antibiotic prescription in pneumonia, ranging from 69 to 93%. The study with the lowest prescription (3) included children <6 years only compared to the other four (including children in the range of 1-18 years). Antibiotic prescription in RTI other (6 studies) varied on a broader range from 17 to 51%, but could not be related to age. Only two studies provided information on antibiotic prescription in UTI, ranging from 66 to 70%.

Type of antibiotic prescription

Nine out of 26 (35%) studies [two high quality (30, 56)] reported on antibiotic type (Figure 4). Six studies addressed respiratory tract infections (19, 30, 43, 56, 57, 63) and five were conducted in the US (19, 30, 32, 57, 63). We did not observe a predominance for one antibiotic type for a specific diagnosis or country; amoxicillin was always reported. Studies describing cephalosporin use (n = 7) included both second or third generations.

Figure 4.

Type of antibiotic as percentage of total antibiotics prescribed per study. *As defined in article. Ahmed et al. (19): not specified; Copp et al. (32): nitrofurantoin and others are not specified antibiotics. Coco et al. (30): not specified. Ochoa et al. (56): trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, fosfomycin, rifampin, trimethoprim, topical use and others are not specified. Ong et al. (57): trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; Shah et al. (63): not specified. ∧Calculated from article as percentage of total antibiotics, in article given as percentage of cases.

Prescribing physician

Five (39, 42, 47, 63, 72) out of seven studies [three high quality studies (44, 47, 66)], reported significant lower antibiotic prescriptions by pediatric emergency physicians compared to general emergency physicians (Table 3). Two addressed young children with fever without source (39, 42), and five addressed older children with respiratory tract infections (19, 44, 47, 63, 65).

Table 3.

Difference in antibiotic prescription between general physicians and pediatric physicians.

| Reference, Country | N Antibiotics given by GEMP/N seen by GEMP % antibiotics | N antibiotics given by PEMP/N seen by PEMP % antibiotics | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isaacman et al. (39), US | 37/79, 39% | 83/498, 17% | FWS |

| Khine et al. (42), US | 97/237, 41% | 61/224, 27% | FWS |

| Ahmed et al. (19), US | NR/238, 32% | NR/345, 17% | URTI |

| Kornblith et al. (44), US | NR, 46% | NR, 42% | ARTI |

| Shah et al. (63), US | 2946, 50% | 520, 35% | Febrile RTI |

| Linder et al. (47), US | NR, 60% | NR, 47% | Sore throat |

| Spiro et al. (65), US* | NR, 30% | NR, 26% | Fever/ARS |

No significant statistical difference was found.

The effect of interventions on antibiotic prescription

Nine out of 27 studies on interventions for antibiotic prescription (32%) reported about rapid viral testing (22, 24, 25, 27, 33, 40, 58, 62, 64), four about delayed antibiotic prescription in acute otitis media (29, 34, 52, 66), six about guideline/management strategies (20, 21, 41, 53, 59, 68), four about laboratory tests (22, 46, 47, 49) and five using other interventions (Table 4). In fourteen studies (50%) a significant reduction in antibiotic use was found.

Table 4.

Influence of intervention on antibiotic prescription.

| Reference, Country | Median (IQR) or Mean age ± SD ¥ | Intervention | Inclusion | N intervention total, % AB | N controls total, % AB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEVER IN GENERAL | |||||

| Aronson et al. (21), US | 46 days (37–53) | CPG recommending ceftriaxone compared to no CPG | Fever | 306, 64.1%∧ | 1.304, 11.7%∧ |

| 45 days (37–53) | |||||

| CPG recommending against ceftriaxone compared to no CPG | 313, 10.9%∧ | 1.304, 11.7%∧ | |||

| Jain et al. (41), US | NR | Physician feedback through scorecards | Fever | 8.961, 10.8% | 1.0114, 12% |

| Lacroix et al. (46), France | 3.4 months (1.5–10.4) | Lab Score | FWS | 131, 41.2% | 140, 42.1% |

| 4.8 months (1.7–10.4) | |||||

| Manzano et al. (49), Canada | 12 ± 8 months° | PCT testing | Fever | 192, 25% | 192, 28% |

| 12 ± 8 months° | |||||

| Murray et al. (53), US | 36 days ± 13.8 | Implementation of a clinical pathway | Fever | 296, 69% | 224, 72% |

| de Vos-Kerkhof et al. (68), Netherlands | 1.7 years (0.8–3.9) | Clinical decision model | Fever | 219, 35.6% | 220, 41.8% |

| 2.0 years (1.0–4.2) | |||||

| (SUSPICION OF) BACTERIAL INFECTIONS | |||||

| Nelson et al. (54), US * | 2.8 years (4.4) | Antibiotic prescription rate before and after CXR result | Pneumonia | 1610, 23% | 1610, 7% |

| de Vos-Kerkhof et al. (68), Netherlands | 1.8 (0.9–4.1) | Clinical decision model | Fever and SBI | 192, 22.9% | 192, 27.1% |

| Waddle and Jhaveri (69), US | 17 months ± 11° | PCV7 | FWS and BC | 275, 57.2% | 148, 60.8% |

| 15 months ± 10° | |||||

| INFLUENZA | |||||

| Blaschke 2014 (25), US◇ | 53% < 18 years | Rapid viral testing (positive/negative RVT) | RVT performed | NR, 11% | NR, 47% |

| Benito-Fernández et al. (24), Spain | 6.86 months ± 6.3° | Rapid viral testing (positive/negative RVT) | Fever without source | 84, 0% | 122, 38.5% |

| 6.55 months ± 6.8° | |||||

| Bonner et al. (27), US | NR | Rapid viral testing (RVT /no RVT) | Influenza positive | 96, 7% | 106, 25% |

| Doan et al. (33), Canada | 15 months (3–36) | Rapid viral testing (POCT/standard testing) | Acute respiratory symptoms | 89, 18% | 110, 21% |

| 14 months (4–34) | |||||

| Iyer et al. (40), US | ±75% 6–24 months | Rapid viral testing (RVT/ no RVT) | Fever | 345, 25.3% | 355, 30.5% |

| Li-Kim-Moy et al. (48), Australia | 3.1 years (1.1–7.4) | Rapid viral testing (POCT/standard testing) | Lab proven influenza | 236, 33% | 65, 54% |

| Özkaya et al. (58), Turkey | 5.7 years ± 3.4° | Rapid viral testing (RVT /no RVT) | Influenza-like illness | 50, 58% | 47, 100% |

| 4.25 years ± 2.02° | |||||

| Poehling et al. (62), US | NR | Rapid viral testing (RVT/no RVT) | Fever or ARS during influenza season | 135, 32% | 170, 29% |

| Sharma et al. (64), US | 9 months° | Rapid viral testing (RVT /no RVT) | Fever and positive influenza test | 47, 2% | 25, 24% |

| AOM | |||||

| Chao et al. (29), US | 5.01 years (3.67–6.68) | Delayed prescription with and without prescription | AOM | 100, 19% | 106, 46% |

| 3.73 years (2.82–5.75) | |||||

| Fischer et al. (34), US | 68% 2–6 years | Wait-and-see prescription in AOM | AOM | 144, 27% | N.A. |

| McCormick et al. (52), US | ±60% < 1 years | Wait-and-see prescription in AOM | AOM | 100, 34% | 109, 100% |

| Nibhanipudi et al. (55), US* | 5.72 years ± 0.38° (m) | WBC >15.000 or WBC < 15.000 | AOM | 93, 3% | 7, 100% |

| 7.41 years ± 0.75° (f) | |||||

| Spiro et al. (66), US | 3.2 years | Wait-and-see prescription in AOM | AOM | 138, 38% | 145, 87% |

| 3.6 years | |||||

| RTI Other | |||||

| Angoulvant et al. (20), France | 17 months (7–40) | Implementing guidelines | ARTI | NR, 21% | NR, 32.1% |

| Ayanruoh et al. (22), US | NR | Rapid streptococcal testing | Clinical diagnosis of pharyngitis | 6.557, 22.45% | 1.723, 41.38% |

| Linder et al. (47), US | 45% 6–11 years | GABHS testing in sore throat | Sore throat | NR, 48% | NR, 51% |

| Ouldali et al. (59), France | 1.6 years (0.7–3.6) | Implementation of national guidelines | ARTI | 134.450,−28.4% | 61.612 |

| 1.7 years (0.7–3.7) | |||||

| Spiro et al. (65), US | 17.3 months° | Tympanometry for reduction antibiotics in AOM | Fever or ARS | 341, 28.8% | 340, 26.8% |

| 17.2 months° | |||||

| Wheeler et al. (70), US | 3 years (1 months−20 years) | Videotape in waiting room | Viral infections | 71, 4.2% | 73, 6.8% |

Only parenteral antibiotic prescription rate is given. Highlighted studies indicate studies with significant results.

Estimated/calculated from numbers in article.

Mean age given, median age not reported.

Interventions for AOM

Interventions with a significant effect on antibiotic reduction were guidelines and the wait-and-see prescription in acute otitis media (AOM). For this latter a significant reduction was found in four articles (three of them with moderate to high quality) (29, 34, 52, 66).

Viral testing intervention

Most studies on interventions for reduction of antibiotic prescription addressed rapid viral testing for influenza (RVT, n = 9). Fewer antibiotics were prescribed when the RVT is positive (24, 25, 27, 64), although not confirmed by studies on the impact of RVT use vs. not using RVT in the ED (27, 40, 58, 62). Only one low quality study reported a significant difference for this topic (58). The use of point-of-care testing above testing on indication had only significant benefit in children with proven influenza (33, 48). One study reported reduced length of stay, but no effect on antibiotic prescription (48).

Other interventions

Three high quality studies showed a significant reduction in antibiotic prescription by a guideline for lower respiratory infections or infants with fever (20, 21, 41). Among two articles on streptococcal A testing, the article with the highest quality didn't find a significant reduction (22, 47). Introduction of a clinical pathway for young febrile infants showed reduced time to first antibiotic dose, but did not evaluate the effect on antibiotic prescription itself (53). The use of chest radiographs in particular reduces antibiotics in children with low clinical suspicion of pneumonia (54). For all other interventions no significant reduction was found on antibiotic prescription (46, 49, 65, 69, 70).

Discussion

Interpretation of main findings

We observed a highly variable reported antibiotic prescriptions in children presenting to a general or pediatric ED in the five major groups of diagnosis. Studies on a specific diagnosis, such as AOM, pneumonia, or UTI report higher antibiotic prescriptions. However, studies are too heterogeneous to study true effects of determinants. Strong evidence was found for watchful waiting in AOM and implementation of guidelines for fever or respiratory infections to reduce antibiotic use in the ED. Intervention studies report mostly on rapid viral testing for influenzae (RVT) to reduce antibiotic prescription, but its effect is controversial.

It is important to note that the high variability in antibiotic prescription observed in our systematic review differ from reported antibiotic prescriptions from literature, or websites (12, 73). However, these numbers are based on national or local registries and include in-hospital patients, not reflecting our interest on use of antibiotics in ED settings. Next, not all countries are represented in our systematic review and only Switzerland, USA are represented by more than one study. For the latter two, however we observed high variability in antibiotic prescription within studies of the same country. Even within studies focusing on similar group of diagnoses, we observed a large heterogeneity in their way of patient selection and their type of febrile illness. Therefore, we think these antibiotic prescriptions cannot be considered to be representative for the general population of febrile children in a country.

Limited evidence was found for age effects on antibiotic prescriptions, potentially due to age distribution among study populations. Infants below 2 months are underrepresented in our review. From community studies, we know that pre-school children are more frequently exposed to antibiotic therapy (13).

After exclusion of two outlier studies given their patient selection and outcome definition (42, 50), we observed in studies on children with fever a trend toward higher antibiotic prescriptions in studies with higher SBI rates is noticeable. This, however, only explains some variation in antibiotic prescription.

Similar to studies in primary care, watchful waiting intervention seems highly effective for reducing antibiotic use in AOM at the ED (74). Results however are limited to patients above the age of 6 months that did not appear toxic and it is questionable if the study populations were large enough to detect serious adverse outcomes such as meningitis. Although the most frequently studied intervention, rapid viral testing for influenza has no additional effect above testing on indication and controversial evidence was found for its effect. Effects of guidelines are seen in two well-defined groups (respiratory infections or young febrile infants) and including a well-defined implementation plan. Implementation of a clinical decision model to reduce antibiotic prescriptions was only tested in a tertiary pediatric university ED and antibiotic reduction was not a primary outcome of this study (17). All other interventions are not (yet) proven to be effective for reducing the antibiotic prescriptions in children on the ED. Overall the evidence to reduce antibiotic prescription in the emergency department remains limited. We observed a general association between antibiotic prescription and the type of prescriber, i.e., pediatricians prescribe less antibiotics than general physicians may suggest that guideline implementation could be most effective in hospitals with general physicians treating children in the ED.

Limitations

The quality of the studies that reported about fever in general was low to moderate, with only one high quality study (3). Specific drawbacks of study design are included in the MINOR assessment as a measure of quality. The use of MINORS in combination with the study population and study aim helps to increase the reproducibility of this review and made it possible to compare the different levels of evidence (16). Most studies did not reported on missing values regarding antibiotic prescription, which could lead to an underestimation of antibiotic prescriptions. In a substantial part of the included papers, antibiotic prescription was not the primary outcome. This may explain some diversity in antibiotic prescriptions, although this was partially corrected for in the quality assessment.

This systematic review focuses on prescription of antibiotics in the ED setting. In many European countries, antibiotics are available as over the counter drugs as well (75). This issue is not accounted for by any of the articles, which may lead to a general underestimation of the antibiotic use.

Unfortunately, we observed a large heterogeneity of the studies or had only 1 study per diagnosis group, hampering meta-analysis. Most heterogeneity is caused by specific patient selection (age, setting), by study design (intervention vs. observational cohort study). This also applies to the population of febrile children <36 months that constitute the majority of ED attendances.

Future research recommendations

To validly estimate baseline antibiotic prescriptions in children with fever presenting to the emergency department we need observational studies including the general spectrum of febrile children. Being able to determine influences of antibiotic prescription, we should address geographical and cultural influences, differences in setting, adherence area, general patient characteristics, and descriptors of illness severity. Insight in these determinants may help to define targets for intervention to reduce antibiotic prescriptions. Next, this information will contribute to valid power calculations for intervention studies and to generalize effects to other settings.

Conclusion

A summary of studies on antibiotic prescription in the 5 main diagnostic groups at the ED did not yield uniform outcomes. There seems to be a trend toward higher antibiotic prescriptions in younger children and for diagnoses that are more often related to bacterial infections. Delayed antibiotic prescription in children with acute otitis media and guidelines for fever/LRTI seem useful to reduce antibiotic prescriptions at the ED. However no strict conclusions can be drawn on the basis of this review because of the large heterogeneity of type of studies and included populations. This means that there is still a gap in knowledge on the determining factors that influence antibiotic prescription in febrile children presenting to the ED. A multicentre study including a wide range of countries on a general population of febrile children would be recommended to provide a valid baseline of antibiotic prescriptions in general, and influencing factors that identify targets for future interventions.

Author contributions

EvdV was responsible for search, dataextraction and writing of the manuscript. HM, SM, and AG contributed to datainterpretation and writing of the manuscript. RO concepted the idea of the paper, supervised search, dataextraction, and writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AB

antibiotic(s)

- AOM

acute otitis media

- ARS

acute respiratory symptoms

- ARTI

acute respiratory tract infection

- BC

blood culture

- CAP

community acquired pneumonia

- CC

case control study

- CI

confidence interval

- CP

cohort study prospective

- CR

cohort study retrospective

- CS

cross sectional study

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- d

days

- ED

emergency department

- EL

extreme leukocytosis

- FWS

fever without source

- GED

general emergency department

- GEMP

general emergency medicine physician

- ILI

influenza-like illness

- ML

moderate leukocytosis

- mo

months

- NR

not reported

- NS

not specified

- PED

pediatric emergency department

- PEMP

pediatric emergency medicine physician

- qRCT

quasi-randomized controlled trial

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- reg

registration

- RIDT

rapid influenza diagnostic tests

- RST

rapid streptococcal test

- RVT

rapid viral testing

- SBI

serious bacterial infection

- SD

standard deviation

- T

temperature

- URTI

upper respiratory tract infection

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- y

years.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2018.00260/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Fields E, Chard J, Murphy MS, Richardson M, Guideline Development G, Technical T. Assessment and initial management of feverish illness in children younger than 5 years: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ (2013) 346:f2866. 10.1136/bmj.f2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nijman RG, Vergouwe Y, Thompson M, van Veen M, van Meurs AH, van der Lei J, et al. Clinical prediction model to aid emergency doctors managing febrile children at risk of serious bacterial infections: diagnostic study. BMJ (2013) 346:f1706. 10.1136/bmj.f1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig JC, Williams GJ, Jones M, Codarini M, Macaskill P, Hayen A, et al. The accuracy of clinical symptoms and signs for the diagnosis of serious bacterial infection in young febrile children: Prospective cohort study of 15 781 febrile illnesses. BMJ (2010) 340:1015. 10.1136/bmj.c1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brett A, Bielicki J, Newland JG, Rodrigues F, Schaad UB, Sharland M. Neonatal and pediatric antimicrobial stewardship programs in europe - defining the research agenda. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2013) 32:e456–65. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31829f0460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otters HB, van der Wouden JC, Schellevis FG, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, Koes BW. Trends in prescribing antibiotics for children in Dutch general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. (2004) 53:361–6. 10.1093/jac/dkh062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair PS, Turnbull S, Ingram J, Redmond N, Lucas PJ, Cabral C, et al. Feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of a within-consultation intervention to reduce antibiotic prescribing for children presenting to primary care with acute respiratory tract infection and cough. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e014506. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stille CJ, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Kotch JB, Finkelstein JA. Physician responses to a community-level trial promoting judicious antibiotic use. Ann Fam Med. (2008) 6:206–12. 10.1370/afm.839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, Friedberg MW, Persell SD, Goldstein NJ, et al. Effect of behavioral interventions on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care practices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA (2016) 315:562–70. 10.1001/jama.2016.0275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, Fenelon L, Gould IM, Holmes A, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) 2:CD003543. 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman JM. Appropriate antibiotic use and why it is important: the challenges of bacterial resistance. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2003) 22:1143–51. 10.1097/01.inf.0000101851.57263.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Versporten A, Sharland M, Bielicki J, Drapier N, Vankerckhoven V, Goossens H, et al. The antibiotic resistance and prescribing in European Children project: a neonatal and pediatric antimicrobial web-based point prevalence survey in 73 hospitals worldwide. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2013) 32:e242–53. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318286c612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molstad S, Lundborg CS, Karlsson AK, Cars O. Antibiotic prescription rates vary markedly between 13 European countries. Scand J Infect Dis. (2002) 34:366–71. 10.1080/00365540110080034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossignoli A, Clavenna A, Bonati M. Antibiotic prescription and prevalence rate in the outpatient paediatric population: analysis of surveys published during 2000–2005. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2007) 63:1099–106. 10.1007/s00228-007-0376-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan J, Greene SK, Kleinma KP, Lakoma MD. Trends in antibiotic use in massachusetts children, 2000-2009. J Emerg Med. (2012) 43:e381 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, Caudron Q, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, et al. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. (2014) 14:742–50. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70780-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. (2003) 73:712–6. 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Vos-Kerkhof E, Geurts DH, Wiggers M, Moll HA, Oostenbrink R. Tools for 'safety netting' in common paediatric illnesses: a systematic review in emergency care. Arch Dis Child. (2016) 101:131–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L, Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review G. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine (2003) 28:1290–9. 10.1097/01.BRS.0000065484.95996.AF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed MN, Muyot MM, Begum S, Smith P. Antibiotic prescription pattern for viral respiratory illness in emergency room and ambulatory care settings. Clin Pediatr. (2010). 49:452–7. 10.1177/0009922809357786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angoulvant F, Skurnik D, Bellanger H, Abdoul H. Impact of implementing French antibiotic guidelines for acute respiratory-tract infections in a paediatric emergency department, 2005–2009. Eur J Ofin Microbiol Infect Dis. (2011) 31:1295–303. 10.1007/s10096-011-1442-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aronson PL, Thurm C, Williams DJ, Nigrovic LE, Alpern ER, Tieder JS, et al. Association of clinical practice guidelines with emergency department management of febrile infants ≤ 56 days of age. J Hosp Med. (2015) 10:358–65. 10.1002/jhm.2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayanruoh S, Waseem M, Quee F. Impact of rapid streptococcal test on antibiotic use in a pediatric emergency department. Ped Emerg Care (2009) 25:748–50. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181bec88c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benin AL, Vitkauskas G, Thornquist E, Shiffman RN, Concato J, Krumholz HM, et al. Improving diagnostic testing and reducing overuse of antibiotics for children with pharyngitis: a useful role for the electronic medical record. Pediatric Infect Dis J. (2003) 22:1043–7. 10.1097/01.inf.0000100577.76542.af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benito-Fernandez J, Vazquez-Ronco MA, Morteruel-Aizkuren E, Mintegui-Raso S, Sanchez-Etxaniz J, Fernandez-Landaluce A. Impact of rapid viral testing for influenza A and B viruses on management of febrile infants without signs of focal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2006) 25:1153–7. 10.1097/01.inf.0000246826.93142.b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blaschke AJ, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Byington CL, Ampofo K, Stockmann C, et al. A national study of the impact of rapid influenza testing on clinical care in the emergency department. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. (2014) 3:112–8. 10.1093/jpids/pit071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brauner M, Goldman M, Kozer E. Extreme leucocytosis and the risk of serious bacterial infections in febrile children. Arch Dis Childhood. (2010) 95:209–12. 10.1136/adc.2009.170969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonner AB, Monroe KW, Talley LI, Klasner AE, Kimberlin DW. Impact of the rapid diagnosis of influenza on physician decision-making and patient management in the pediatric emergency department: results of a randomized, prospective, controlled trial. Pediatrics (2003) 112:363–7. 10.1542/peds.112.2.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bustinduy AL, Chis Ster I, Shaw R, Irwin A, Thiagarajan J, Beynon R, et al. Predictors of fever-related admissions to a paediatric assessment unit, ward and reattendances in a South London emergency department: the CABIN 2 study. Arch Dis Child. (2017) 102:22–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chao JH, Kunkov S, Reyes LB, Lichten S, Crain EF. Comparison of two approaches to observation therapy for acute otitis media in the emergency department. Pediatrics (2008) 121:1352–6. 10.1542/peds.2007-2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coco AS, Horst MA, Gambler AS. Trends in broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing for children with acute otitis media in the United States, 1998-2004. BMC Pediatr. (2009) 9:41. 10.1186/1471-2431-9-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colvin JM, Muenzer JT, Jaffe DM, Smason A, Deych E, Shannon WD, et al. Detection of viruses in young children with fever without an apparent source. Pediatrics (2012) 130:e1455–e62. 10.1542/peds.2012-1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Copp HL, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL. National ambulatory antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric urinary tract infection, 1998-2007. Pediatrics (2011) 127:1027–33. 10.1542/peds.2010-3465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doan QH, Kissoon N, Dobson S, Whitehouse S, Cochrane D, Schmidt B, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of the impact of early and rapid diagnosis of viral infections in children brought to an emergency department with febrile respiratory tract illnesses. J Pediatr. (2009) 154:91–5. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer T, Singer AJ, Chale S. Observation option for acute otitis media in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care (2009) 25:575–8. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181b91ff0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galetto-Lacour A, Zamora SA, Gervaix A. Bedside procalcitonin and C-reactive protein tests in children with fever without localizing signs of infection seen in a referral center. Pediatrics (2003) 112:1054–60 10.1542/peds.112.5.1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldman RD, Scolnik D, Chauvin-Kimoff L, Farion KJ, Ali S, Lynch T, et al. Practice variations in the treatment of febrile infants among pediatric emergency physicians. Pediatrics (2009) 124:439–45. 10.1542/peds.2007-3736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Houten CB, de Groot JAH, Klein A, Srugo I, Chistyakov I, de Waal W, et al. A host-protein based assay to differentiate between bacterial and viral infections in preschool children (OPPORTUNITY): a double-blind, multicentre, validation study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2017) 17:431–40. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30519-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irwin AD, Grant A, Williams R, Kolamunnage-Dona R, Drew RJ, Paulus S, et al. Predicting risk of serious bacterial infections in febrile children in the emergency department. Pediatrics (2017) 140:e20162853. 10.1542/peds.2016-2853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isaacman DJ, Kaminer K, Veligeti H, Jones M, Davis P, Mason JD. Comparative practice patterns of emergency medicine physicians and pediatric emergency medicine physicians managing fever in young children. Pediatrics (2001) 108:354–8. 10.1542/peds.108.2.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iyer SB, Gerber MA, Pomerantz WJ, Mortensen JE, Ruddy RM. Effect of point-of-care influenza testing on management of febrile children. Acad Emerg Med. (2006) 13:1259–68. 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain S, Frank G, McCormick K, Wu B, Johnson BA. Impact of physician scorecards on emergency department resource use, quality, and efficiency. Pediatrics (2015) 136:e670–e9. 10.1542/peds.2014-2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khine H, Goldman DL, Avner JR. Management of fever in postpneumococcal vaccine era: comparison of management practices by pediatric emergency medicine and general emergency medicine physicians. Emerg Med Int. (2014) 2014:702053. 10.1155/2014/702053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kilic A, Unuvar E, Sutcu M, Suleyman A, Tamay Z, Yildiz I, et al. Acute obstructive respiratory tract diseases in a pediatric emergency unit: Evidence-based evaluation. Pediatr Emerg Care (2012) 28:1321–7. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182768d17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kornblith AE, Fahimi J, Kanzaria HK, Wang RC. Predictors for under-prescribing antibiotics in children with respiratory infections requiring antibiotics. Am J Emerg Med. (2018) 36:218–25. 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kronman MP, Hersh AL, Feng R, Huang YS. Ambulatory visit rates and antibiotic prescribing for children with pneumonia, 1994–2007. Pediatrics (2011) 127:411–18. 10.1542/peds.2010-2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lacroix L, Manzano S, Vandertuin L, Hugon F, Galetto-Lacour A, Gervaix A. Impact of the lab-score on antibiotic prescription rate in children with fever without source: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e0115061. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linder JA, Bates DW, Lee GM, Finkelstein JA. Antibiotic treatment of children with sore throat. JAMA (2005) 294:2315–22. 10.1001/jama.294.18.2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li-Kim-Moy J, Dastouri F, Rashid H, Khandaker G, Kesson A, McCaskill M, et al. Utility of early influenza diagnosis through point-of-care testing in children presenting to an emergency department. J Paediatr Child Health (2016) 52:422–9. 10.1111/jpc.13092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manzano S, Bailey B, Girodias JB, Galetto-Lacour A, Cousineau J, Delvin E. Impact of procalcitonin on the management of children aged 1 to 36 months presenting with fever without source: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. (2010) 28: 647–53. 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Massin MM, Montesanti J, Lepage P. Management of fever without source in young children presenting to an emergency room. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. (2006) 95:1446–50. 10.1080/08035250600669751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCaig LF, McDonald LC, Cohen AL, Kuehnert MJ. Increasing blood culture use at US Hospital Emergency Department visits, 2001 to 2004. Ann Emerg Med. (2007) 50:42–48.e2 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCormick DP, Chonmaitree T, Pittman C, Saeed K. Nonsevere acute otitis media: a clinical trial comparing outcomes of watchful waiting versus immediate antibiotic treatment. Am Acad Pediatrics (2005) 115:1455–65. 10.1542/peds.2004-1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murray AL, Alpern E, Lavelle J, Mollen C. Clinical pathway effectiveness: febrile young infant clinical pathway in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care (2017) 33:e33–e7. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nelson KA, Morrow C, Wingerter SL, Bachur RG, Neuman MI. Impact of chest radiography on antibiotic treatment for children with suspected pneumonia. Pediatr Emerg Care (2016) 32:514–9. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nibhanipudi KV, Hassan GW, Jain A. The utility of peripheral white blood cell count in cases of acute otitis media in children between 2 years and 17 years of age. Int J Otorhinolaryngol. (2016) 18 10.5580/IJORL.38086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ochoa C, Inglada L, Eiros JM, Solis G, Vallano A, Guerra L, et al. Appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions in community-acquired acute pediatric respiratory infections in Spanish emergency rooms. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2001) 20:751–8. 10.1097/00006454-200108000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ong S, Nakase J, Moran GJ, Karras DJ. Antibiotic use for emergency department patients with upper respiratory infections: prescribing practices, patient expectations, and patient satisfaction. Ann Emerg Med. (2007) 50:213–20. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ozkaya E, Cambaz N, Coskun Y, Mete F, Geyik M, Samanci N. The effect of rapid diagnostic testing for influenza on the reduction of antibiotic use in paediatric emergency department. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. (2009) 98:1589–92. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01384.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ouldali N, Bellettre X, Milcent K, Guedj R, de Pontual L, Cojocaru B, et al. Impact of implementing national guidelines on antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory tract infections in pediatric emergency departments: an interrupted time series analysis. Clin Infect Dis. (2017) 65:1469–76. 10.1093/cid/cix590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Planas AM, Almagro CM, Cubells CL, Julian AN, Selva L, Fernandez JP, et al. Low prevalence of invasive bacterial infection in febrile infants under 3 months of age with enterovirus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2012) 18:856–61. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ploin D, Gillet Y, Morfin F, Fouilhoux A, Billaud G, Liberas S, et al. Influenza burden in febrile infants and young children in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2007) 26:142–7. 10.1097/01.inf.0000253062.41648.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poehling KA, Zhu Y, Tang YW, Edwards K. Accuracy and impact of a point-of-care rapid influenza test in young children with respiratory illnesses. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2006) 160:713–8. 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shah S, Bourgeois F, Mannix R, Nelson K, Bachur R, Neuman MI. Emergency department management of febrile respiratory illness in children. Pediatr Emerg Care (2016) 32:429–34. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharma V, Denise Dowd M, Slaughter AJ, Simon SD. Effect of rapid diagnosis of influenza virus type A on the emergency department management of febrile infants and toddlers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2002) 156:41–3. 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spiro DM, King WD, Arnold DH, Johnston C, Baldwin S. A randomized clinical trial to assess the effects of tympanometry on the diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media. Pediatrics (2004) 114:177–81. 10.1542/peds.114.1.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spiro DM, Tay KY, Arnold DH, Dziura JD, Baker MD, Shapiro ED. Wait-and-see prescription for the treatment of acute otitis media: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. (2006) 296:1235–41. 10.1001/jama.296.10.1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trautner BW, Caviness AC, Gerlacher GR. Prospective evaluation of the risk of serious bacterial infection in children who present to the emergency department with hyperpyrexia (temperature of 106 F or higher). Pediatrics (2006) 118:34–40. 10.1542/peds.2005-2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Vos-Kerkhof E, Nijman RG, Vergouwe Y, Polinder S, Steyerberg EW, van der Lei J, et al. Impact of a clinical decision model for febrile children at risk for serious bacterial infections at the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e0127620. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waddle E, Jhaveri R. Outcomes of febrile children without localising signs after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Arch Dis Child. (2008) 94:144–7. 10.1136/adc.2007.130583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wheeler JG, Fair M, Simpson PM, Rowlands LA. Impact of a waiting room videotape message on parent attitudes toward pediatric antibiotic use. Pediatrics (2001) 108:591–6. 10.1542/peds.108.3.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lacour AG, Zamora SA, Vadas L, Lombard PR, Dayer JM, et al. Procalcitonin, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1 receptor antagonist and C-reactive protein as identificators of serious bacterial infections in children with fever without localising signs. Eur J Pediatr. (2001) 160:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ahmed A, Brito F, Goto C, Hickey SM, Olsen KD, Trujillo M, et al. Clinical utility of the polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of enteroviral meningitis in infancy. J Pediatr. (1997) 131:393–7. 10.1016/S0022-3476(97)80064-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.The Center for Disease DynamicsEconomy and Policy. Antibiotic Prescribing Rates by Country. Available online at: www.cddep.org (Accessed July 20, 2018).

- 74.Tyrstrup M, Beckman A, Molstad S, Engstrom S, Lannering C, Melander E, et al. Reduction in antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections in Swedish primary care-a retrospective study of electronic patient records. BMC Infect Dis. (2016) 16:709. 10.1186/s12879-016-2018-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Both L, Botgros R, Cavaleri M. Analysis of licensed over-the-counter (OTC) antibiotics in the European Union and Norway, 2012. Euro Surveill. (2015) 20:30002. 10.2807/1560.7917.ES.2015.20.34.30002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.