Abstract

Osteoid osteoma is a benign bone-forming tumor with hallmark of tumor cells directly forming mature bone. Osteoid osteoma accounts for around 5% of all bone tumors and 11% of benign bone tumors with a male predilection. It occurs predominantly in long bones of the appendicular skeleton. According to Musculoskeletal Tumor Society staging system for benign tumors, osteoid osteoma is a stage-2 lesion. It is classified based on location as cortical, cancellous, or subperiosteal. Nocturnal pain is the most common symptom that usually responds to salicyclates and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. CT is the modality of choice not only for diagnosis but also for specifying location of the lesion, i.e. cortical vs sub periosteal or medullary. Non-operative treatment can be considered as an option since the natural history of osteoid osteoma is that of spontaneous healing. Surgical treatment is an option for patients with severe pain and those not responding to NSAIDs. Available surgical procedures include radiofrequency (RF) ablation, CT-guided percutaneous excision and en bloc resection.

Key words: Osteoid osteoma, tumor, benign, imaging, pathogenesis, management

Introduction

Osteoid osteoma is a benign bone-forming tumor with hallmark of tumor cells directly forming mature bone.1 These are small, distinctive, nonprogressive, benign osteoblastic lesions. Bergstrand first described osteoid osteoma in 1930 and Jaffe in 1935 characterized it as a benign osteoblastic tumor.2,3

Epidemiology

Osteoid osteoma accounts for around 5% of all bone tumors and 11% of benign bone tumors.4 Osteoid osteoma is the third most common biopsy analyzed benign bone tumor after osteochondroma and nonossifying fibroma. Two to 3% of excised primary bone tumors are osteoid osteomas.5 Males are more commonly affected with an approximate male/female ratio of 2 to 1.5 Adolescents and young adults are usually affected in the second decade of life, with most patients being under the age of 20 years. It is less likely to be seen in patients under 5 years of age or in adults greater than 40 years.4

Localisation

Osteoid osteoma occurs predominantly in the appendicular skeleton. Spine is involved in one tenth of the cases.6 Flat bones with intramembraneous formation in the body and skull are rarely affected. The lower extremity is more commonly affected than the upper extremity as shown in Figure 1. Commonly long bones particularly the femur and tibia are involved, followed far behind by bones of the feet, with a predilection for the talar neck. Common sites of femoral involvement are the juxta- or intraarticular regions of the femoral neck. In the upper extremity, phalanges of the hand are commonly affected.4

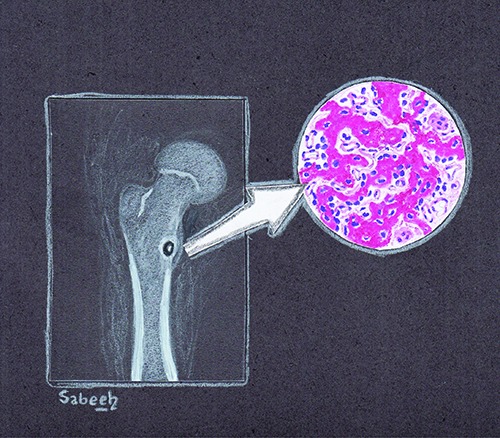

Figure 1.

Pictorial representation of osteoid osteoma.

Classification

In long bones, osteoid osteoma is more often situated in the cortico-diaphyseal or metaphyseal regions, but other localizations such as intramedullary, subperiosteal, epiphyseal or apophyseal have also been noted.6 It is very rare to have two osteoid osteomas in the same patient.4

According to Musculoskeletal Tumor Society staging system for benign tumors, osteoid osteoma is a stage-2 lesion. It is classified as cortical, cancellous, or subperiosteal. Cortical lesions are most common.4

Clinical presentation

Pain is the most common symptom. Usually it is a dull ache, which is unremitting and starts off as mild and intermittent that gradually increases in intensity and persistence. The pain has a tendency to become increasingly severe at night and usually responds to salicyclates and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. If osteoid osteoma involves a bone in a subcutaneous location, then the patient usually presents with swelling, erythema and tenderness.

If the proximal femur or pelvis is involved, the patient can present with referred pain in the knee. Lesions that are within the joint or juxta-articular can present with synovitis. If this continues to progress, the patient can present with joint pain, flexion contracture, decreased range of motion, and a limp or antalgic gait. Sometimes in children, a limp may be the only presenting symptom. If the lesion involves the open physis, it can result in limb length discrepancy with potential coronal and/or sagittal malalignment.

Referred pain and muscle atrophy can result in misdiagnosis of a neurological disorder commonly seen in axial skeleton involvement with postural scoliosis due to paravertebral muscle spasm, which is reversible after treatment.7

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of osteoid osteoma remains unknown. High levels of prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin have been found within the nidus that is believed to cause local inflammation and vasodilatation. A study by Mungo et al.8 revealed increased levels of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in nidus osteoblasts. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition is believed to be a mechanism by which NSAIDs provide symptomatic relief in osteoid osteomas. These inflammatory mediators may also contribute to perilesional sclerosis exhibited by most osteoid osteomas. In addition, high concentrations of intralesional unmyelinated nerve fibers have been implicated in the pathogenesis of the exquisite nocturnal pain. These processes probably function in parallel to produce the characteristic inflammatory symptoms.9,10

Historically, there has been debate over the years about the precise nature of osteoid osteomas. Initially considered a neoplasm by Jaffe, other investigators proposed a reactive or reparative process citing its limited growth potential and its ability to spontaneously regress in some cases.2 Currently, most pathologists agree about the neoplastic nature of osteoid osteomas. The tumour’s histological similarity to osteoblastoma supports the belief that it is a benign tumour derived from the osteoblasts. There have been few cytogenetic studies that reported clonal cytogenetic abnormalities, including alterations involving chromosome 22q, a region which contains genes involved in cell proliferation that is commonly affected in a variety of other neoplasms.11

Gross features

When removed intact, osteoid osteomas are usually small, and round to oval in shape. The cut surface is red to pink when fresh, and brown to granular after formalin fixation. They are well demarcated from the surrounding white sclerotic cortical bone. The nidus color is related to vascularity of intertrabecular areas. As osteoid osteomas are now treated by radiofrequency ablation, such intact specimens as described above are rarely received for histopathology.12

Microscopic features

Histologically, the nidus is well circumscribed and composed of haphazardly interanastomosing trabeculae of variably mineralized woven bone. The trabeculae are usually thin and short, but can be sclerotic and broad and are rimmed by a single layer of osteoblasts. Scattered osteoclasts are also present on the surface of bony trabeculae (Figure 2). The osteoblasts are plump, uniform in size and shape and have eccentric nuclei with small nucleoli and open chromatin. Cytoplasm is usually amphophilic. No nuclear pleomorphism or increased mitotic activity is seen. The intertrabecular stroma is loose and fibrovascular (Figure 3). The reactive bone surrounding the nidus is dense cortical or trabecular bone and when the tumor grows closer to the bone surface, it becomes more pronounced. In medullary lesions, it is less pronounced.13

Figure 2.

Histology of osteoid osteoma. The nidus is composed of densely broad sclerotic bone trabecuale show osteoblastic rimming and fibrovascular connective tissue.

Figure 3.

The bony trabeculae can be thin as seen in this image.

The pathologic evaluation of osteoid osteoma has been affected by the increasing use of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or other minimally invasive techniques. The techniques now used include core biopsy or biopsy obtained from a drill procedure. As compared to specimens received by traditional surgery, the yield of diagnostic tissue is lower and tissue findings are often obscured by heat or crushing artifacts. Consequently, pathologists may or may not be able to confirm the diagnosis on smaller, usually fragmented, and frequently distorted fragments of tissue.14

Immunohistochemical features

S100 and neurofilament show nerve fibers involving tumor.15 Osteoid osteomas also show strong nuclear expression for Runx2 and Osterix, which are regulatory transcription factors. This suggests that osteoid osteomas share common genetic pathways with normal skeletal development.16

Differential diagnosis

Osteoid osteoma can be distinguished from other bone forming tumors based on the difference in size, location, pathology, and clinical symptoms.17 A small Brodie abscess with a radiolucent center and surrounding reactive sclerosis can mimic osteoid osteoma. With intracortical Brodie abscess the sequestrum is irregular in shape and the inner margin of the lucency is not smooth, whereas in osteoid osteoma, the inner margins are usually smooth.18,19 Tumors can also mimic osteoid osteomas. Chondroblastomas in epiphyseal locations of children with osteolytic lesions and extensive bone marrow edema and periosteal reaction can resemble osteoid osteoma. However the epiphyseal and intramedullary location is more characteristic for chondroblastomas, whereas osteoid osteomas are usually diaphyseal and intracortical. In the pediatric age group cortical lesions in the tibia caused by osteofibrous dysplasia, adamantinoma and stress fractures produce cortical thickening and proliferation that can be mistaken for osteoid osteomas. In stress fractures, the reactive woven bone network is well oriented around trabeculae of fractured bone. It is not haphazard and lacks the small irregular trabeculae seen in osteoid osteomas. Other lesions such as nonossifying fibromas, enchondromas, eosinophilic granulomas, Perthes disease, tuberculosis, neuromuscular conditions and malignant bone tumors can also be considered. In addition to clinical features, imaging techniques such as CT, bone and SPECT scans can assist in diagnosing the lesion.

Imaging findings

Plain radiography

Osteoid osteoma appears as an oval lytic lesion located within dense cortical bone in the diaphysis surrounded by fusiform cortical bone thickening and sclerosis. The cortical based lucency is less than 2 cm.20 Underlying lytic nidus may not always be visualized due to significant sclerosis. The sclerotic reactive bone often is seen distant from the lesion, in extra capsular location.

The tumor present at subperiosteal location is a rounded sclerotic focus that elevates the periosteum with limited sclerotic reaction. In intramedullary location, these tumors are well-circumscribed with a complete or partially calcified nidus. The surrounding reactive sclerosis can be minimal or absent (Figure 4A). In posterior elements of the spine, osteoid osteomas are difficult to localize. The nidus is not visualized on plain films but additional findings such as scoliosis with concavity at the side of the lesion is seen in these cases.6,21A study done by PARK et al showed 28.6% of osteoid osteoma cases in their study had no plain radiography abnormality despite very typical clinical presentations. Radionuclide imaging was used to diagnose these cases. Therefore in cases where plain radiographs are not conclusive but clinical suspicion is high, further imaging workup should be requested.22

Figure 4.

A 10 years old boy with humeral osteoid osteoma. A) AP radiograph shows radiolucent nidus arrow and surrounding sclerosis. B) Coronal STIR image shows hypointense lesion long arrow (nidus) and perilesional edema (small arrow). C) Axial T1-weighted and corresponding post contrast T1-weighted Fat sat images show hypointense nidus on pre contrast image with intense enhancement on pot contrast images (long arrow). D) Technetium-99 bone scan, AP projection shows focal region of radiotracer uptake, corresponding to tumor nidus (Arrow).

CT

CT is the modality of choice for diagnosis and specifying location of lesion, i.e. cortical vs sub periosteal or medullary. CT shows well-defined nidus as round or oval with low attenuation (Figure 5). Nidus can show mineralization which may be punctate, amorphous or ring like. Surrounding reactive sclerosis can vary from mild sclerosis to extensive periosteal reaction and new bone formation, which may obscure the nidus.6

Figure 5.

A 14 years old boy osteoid osteoma of right femur. A) axial and B) coronal CT images show hypoattenuating nidus with surrounding sclerosis.

For cases where nonoperative management is chosen as the treatment strategy, mineralization of the nidus is considered as a marker of age of the lesion. The mineralization ratio of osteoid osteoma increases significantly with pain duration. Touraine et al. showed that nidus mineralization ratio of osteoid osteoma is positively related to pain duration and may be a marker of tumor age (P=0.007, hazard ratio=0.193). They however reported no association of nidus size with pain duration (P=0.092). In their study, diaphyseal osteoid osteomas displayed a lower ratio of nidus mineralization as compared to those in epiphyseal and metaphyseal locations.23

Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT helps in differentiating osteoid osteoma from bone cysts and chronic osteomyelitis, specifically Brodie abscess which are avascular. In these cases the tumor nidus shows rapid early arterial enhancement and appears hypervascular. 24-26

Spinal osteoid osteoma is better characterized by CT. The nidus is visible as lowdensity area in posterior elements. Surrounding sclerosis of the ipsilateral pedicle, lamina, or transverse process may be present.

Bone scintigraphy

Technetium-99-labeled bone scintigraphy has high sensitivity for confirming diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. The sensitivity of skeletal scintigraphy for detection is 100%.27 On bone scan characteristic feature is very intense, round activity at nidus surrounded by less intensity of reactive bone. This is known as double density sign.28 The increased intensity of nidus is because of increased bone turn over. The less intense peripheral radiotracer uptake, represents the host bone tumor response (Figure 4) The sign is infrequently seen with spinal osteoid osteoma because of less peripheral sclerosis in vertebral bodies.29 A study done by PARK et al found out that all the patients in their study with or without conclusive appearance on plain radiography, were correctly identified on bone scintigraphy. They recommended that if the radionuclide imaging is positive, CT scans should be next imaging modality for further evaluation but in cases where radionuclide imaging is negative, MRI should be done for the diagnosis of other underlying bone pathologies.22

PET

PET may have role in initial diagnosis and post treatment follow-up. A study previously reported that tumor nidus exhibits 18FFDG-avid glucose metabolism, whereas the surrounding sclerosis does not. In follow up cases of radiofrequency ablation (RFA), hypermetabolic activity is absent. Some authors suggested role of PET specifically in cases of spinal osteoid osteoma. But this modality requires more research work to be done to prove its utility in diagnosis and follow up.30-33

In addition to FDGPET/CT, 68Ga- PSMA PET/CT, which is used in prostate cancer staging and restaging, has been used to detecta case of osteoid osteoma. This uptake was likely because of osteoblastic activity in osteoid osteoma but needs further evaluation to investigate its specific role and accuracy in diagnosis of osteoid osteoma.34,35

MRI

MRI is more sensitive than CT scan for detection of reactive changes in soft tissue. MRI is a reliable method of visualizing the nidus. The MRI appearance of nidus depends on its location in the cortex. The closer the lesion is to the medullary zone, the greater the role of MRI in recognizing the nidus compared to CT scan. However, compared to MRI, CT scan is more specific for identifying a nidus.36,37 The appearance of nidus on MRI is variable depending on mineralization and its vascularity. Nidus on MR T1 weighted sequence appears as round lesion, slightly hyper intense to intermediate signals to adjacent muscle and hyper intense to heterogeneous signals on T2 weighted and STIR sequences (Figure 4B and C). Nidus can be hypointense in all sequences, depending on vascularity and mineralization. Tumor enhancement is variable, can be diffuse or heterogeneous (Figure 4C). The surrounding osteosclerosis appears as low signal on both T1- and T2- weighted sequences.38,39 There is high potential of misdiagnosing osteoid osteoma as neoplastic lesion or oversight it when other modalities are not used for diagnosis. Small lesions may be hard to isolate on MRI as nidus signal is frequently similar to that of surrounding cortex.38 Although CT is the modality of choice in diagnosis of osteoid osteoma, but in patients with atypical clinical presentations, in whom the pain does not respond to NSAIDs and where no obvious abnormality on plain roentgenograms is reported, MRI is done to investigate the underlying cause. MRI is more sensitive than CT scan for detection of reactive changes in soft tissue and surrounding bone edema. Klontzas et al. reported that the half-moon sign of bone marrow edema was associated with the presence of osteoid osteoma in femoral neck. The half-moon sign is highly specific and sensitive for presence of osteoid osteoma in the femoral neck with 94.7% specificity and 100% sensitivity and positive and negative predictive values of 91.7% and 100%, respectively (D). But some authors have questioned this high specificity as the half-moon sign of bone marrow edema in femoral neck can be seen in intermediate-grade stress fractures of the femoral neck on MRI. It has therefore been recommended that if clinical features are suggestive of osteoid osteoma, then CT should be performed to determine the presence of a potentially occult nidus on MRI.35

Pitfall of imaging

The diagnosis of osteoid osteoma on imaging can be challenging in cases where there are severe associated inflammatory changes such as a prominent periosteal reaction, exaggerated synovial hypertrophy, joint effusion, extensive bone marrow and soft tissue edema. In cases of significant associated periosteal reaction and soft tissue edema in a young patient, the differential diagnoses of osteomyelitis or malignant bone tumor, such as Ewing sarcoma have to be considered. A small nidus obscured by extensive bone marrow and soft-tissue edema needs to be differentiated from traumatic injury or infection. For accurate and correct radiological diagnosis it is mandatory to identify the nidus.

Treatment

Non-operative

Non-operative treatment can be considered as an option since the natural history of osteoid osteoma is that of spontaneous healing. 40 Moberg40 and Golding41 reported resolution of symptoms with conservative management in osteoid osteoma within 6 to 15 years. Use of aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) decreases this time to 2 to 3 years.42,43 Use of this nonoperative treatment option risks the potential side effects of protracted NSAID treatment. In anatomical areas where osteoid osteoma is not easily accessible surgically, this may be a viable treatment option. However caution should be exercised with this option, as there are some reports that these tumors progress to osteoblastoma with prolonged NSAID treatment.44

Surgical management

Surgical treatment is an option for patients with severe pain and those not responding to NSAIDs. This option should also be considered for those patients not willing to tolerate pain and those at particular risk of long-term renal and gastrointestinal complications of NSAIDs. Moreover in children with open physes, continued presence of these tumors can lead to growth disturbances like limb length discrepancies, scoliosis and osteoarthritis.45 Available procedures include CT-guided radiofrequency (RF) ablation, en bloc resection, and CTguided percutaneous excision.

En bloc resection

For symptomatic relief, the entire nidus has to be excised. Complete removal of the sclerotic reactive bone however, is not required. Preoperative roentgenograms and CT scans delineate the location of the nidus. This resection has the drawback of an open surgical approach with excision of sclerotic bone leaving behind a bone defect which may require bone grafting and internal fixation with consequent restrictions on postoperative activities and weight bearing. With this approach, intraoperative localization of the tumor may be challenging leading to partial removal and potential recurrence. For structurally critical anatomical sites like the femoral neck, one can consider deroofing and curettage. For intra-articular locations of the tumor, arthroscopic excision is a possible option.46

CT guided percutaneous techniques

Over the years, to reduce the surgical morbidity of open procedures, several percutaneous techniques using CT guidance have been used. These include trephine excision, cryoablation, radiofrequency ablation and laser thermocoagulation.47-51 Fine drills, bone trephine, Tru-Cut needles, and cannulated curettes have been used with percutaneous CT guided techniques performed in the outpatient setting. Using percutaneous CT guided resection, Sans and colleagues52 showed a cure rate of 84% at 3.7 years with two complications of femoral fractures at 2 months. For osteoid osteomas of the hip Muscolo and colleagues53 showed superior results of percutaneous resection guided by CT.

Roqueplan and colleagues54 reported percutaneous CT guided trephine resection success rate of 95% at 2 years. Two patients got skin burns and one had meralgia. The same authors reported 94% success rate with interstitial laser ablation at 2 years and complications of infection, tendonitis, hematoma, and common peroneal nerve injury.

Percutaneous thermocoagulation of osteoid osteoma was reported by de Berg and colleagues55 successfully in 17 patients. Hoffman et al.56 reported 5-year results of radiofrequency ablation with confirmed cure in 38 of 39 patients. Complications in this series included one broken drill and one case of infection. Papathanassiou et al.57 in their series of 21 patients over 5 years reported a primary cure rate of 89.6% that increased to 93% if a second treatment was required. Rosenthal and colleagues58 reported their results of CT guided RF ablation in 263 patients. A total of 271 procedures were performed of which 249 were for initial tumor treatment, 14 for recurrence after open excision, and 8 for recurrence after prior RF ablation. They reported 2 minor complications and recommended RF ablation as the treatment of choice with 91% clinical success, brief recovery and low complication rate.

It is important to note that irrespective of the technique used, a biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis. In order to evaluate complete removal of the nidus, several techniques have been used which include roentgenograms, CT scans, and microradiography of specimens. Table l59-118 is a synopsis of the published literature referencing all case series with more than 15 patients listing the treatment and outcomes.

Conclusions

Osteoid osteoma is a distinct benign bone-producing tumor. Nonoperative treatment with NSAIDs is an appropriate option for pain control. Surgical options should be considered when conservative treatment fails or is not indicated for or not opted for by the patient. Minimally invasive methods including CT-guided excision and RF ablation have shown promise with highly successful outcomes.

Table 1.

Synopsis of the published literature.

| s# | Reference/ year | No. of patients | Age of patients (years) | Gender | Sites | Treatment | Duration of follow up | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bousson et al.59 2018 | 23 | Range 8-44 Mean age 23.8 | M 15 F8 | Cervical spine 5, Sacrum 3, Thoracic spine, Femoral neck, Femoral condyle and Tibia 2 cases in each. Lumbar spine, Coccyx Humerus, Iliac bone, Acetabulum, Fibula, neck, and Talus lin each case | Bisphcsphonate therapy | Range 20-48 months (mean 36) | Recurrence of pain in 6 cases |

| 2. | Santiago et at.60 2018 | 21 | Range 17-54 Mean age 29.9 | M 12 F9 | Femur 8, spine 5, talus 2, cuboid 2, humerus, tibia, fibula, and patella 1 case each | Percutaneous cryoablation | Range 6-40 (mean 21 months) | Recurrence in 1 case |

| 3. | Nijland et el.61 2017 | 86 | Mean age 26.1 (±10.7) | M59 F27 | Femur 31, Tibia 29, Fibula 9, others 17 | CT-guided radio frequency ablation | Mean 54.1 (±30.6) | Clinical success rate 81.4% |

| 4. | Wu et al.62 2017 | 72** | Range 3-16 (average, 10.5±4.6) | M22 F14 | Proximal femur 2D, Tibia 6, Ilium 2, 1 case each in calcaneus and ischia | CT-guided radio frequency ablation | 12 months | Recurrence in 1 case |

| 5. | Shields et al.63 2017 | 42 | Mean age 21.1 | M 14 F 28 | Femur 8, Tibia/Fibula 21, humerus and forearm 2 cases in each, Wrist/Hand, Foot and Spine/Pelvis 3 cases in each | Radiofrequency ablation | Range 21 to 137 months (mean 72.3 months) | Recurrence in 7 cases |

| 6. | Quraishi et al.64 2017 | 84 | Range 6.7-52.4 (mean 21.8±9.0) | M65 F19 | Thoracic spine 31, Cervical and lumbar spine 25 cases each, sacrum 3 | Surgical resection | Range 13 days-14.5 (mean 2.7 years) | Recurrence in 6 patients |

| 7. | Erol et al.65 2017 | 47 | Range 4-19 years (mean 10.5 years) | M29 F18 | Femur 21, Tibia 7, Humerus 10, Tibia 7, Radius 2, ulna 1, Proximal phalanx 3, distal phalanx 1, talus 1, metatarsal 1 | Minimal invasive intralesional extended curettage | Range 12-136 months (59 months) | No local recurrence was observed after a minimum follow-up of 12 months |

| 8. | Garge et at.66 2017 | 30 | Range 4-20 years (mean 13.16 years) | M25 F5 | Femur 21, tibia 4, 4 near articular surface (one each at glenoid fossa of right scapula, head of right radius, talocalcalcaneal joint of right calcaneum, and left femoral head) aud 1 in left sacrum | CT-guided percutaneous RFA | Average follow up 6 months | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 9. | Karagöz etal.67 2016 | 18 | Range 10-27 years (mean 17.4 years) | M12 F6 | Femur 8, tibia 7, ulna 1, foot 1, sacrum 1 | CT-guided radiofrequency ablation | Average 26,5 months | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 10. | Miyaraki et el.68 2016 | 21 | Range 10-39 years (median 22 years) | M 17 F4 | Femur 17, Tibia 2, Humerus 1, Rib 1 | Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation | Range 3-35 months (mean 15.1 months) | No recurrence |

| 11. | Masciocchi et al.69 2016 | 30 | Range 19.3-30; median 23 (MRgFUS group) Range 25-31; median 28 (RFA group) | M 18 F 12 | Femur 15, Tibia 5, Talus 5, Humerus 4, Hip 1 | Magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) | Average follow up 12 weeks | No recurrence in RFA group Recurrence in 1 patient in the MRgFUS group |

| 12. | Wallace et al.70 2016 | 18 | Range 5.5-58.2 years (mean 24.1±14.9 years) | M 13 F5 | Femur 9, tibia 4, cervical spine 2, calcaneus 1, iliac bone 1, fibula 1 | Navigational bipolar radiofrequency ablation | Range 34-91 days (median 56 days) | No recurrence |

| 13. | Outani et al.71 2016 | 32 | Range 10 to 39 years (median 20 years) | M 25 F 7 | Femur 18, tibia 7, humerus 2, 1 each in fibula, scapula, patella, Lumbar vertebra, and acetabula | Radiofrequency ablatiou | Range 1 to 65 months (median 18 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 14. | Etemadifar et al.72: 2015 | 19 | Range 8-38 years (mean age of 19.8 | M 11 F8 | Lumbar spine 7, thoracic spine 6, cervical spine 5, sacrum 1 | Surgical intra-lesional curettage | Range 9-115 months (average 44.5 months) | No recurrence |

| 15. | Petrilli et al.73 2015 | 18 | Range 10 to 34 years (mean 18 years) | M 15 F 3 | Femur 7, tibia 6, humerus, ulna, cuneiform, calcaneus and fibula in 1 each. | CT-guided percutaneous trephine resection | Range 6-60 months (median 29 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 16. | Knudsen et al.74 2015 | 52 | Range 6-42 years (mean 18.2 years) | M34 D 18 | Femur 28, Tibia 18, Humerus, ischium, fibula, calcaneous, cuboid, cuneiform 1 case each | CT-guided radio frequency ablation (RFA) | NA | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 17. | Ilamdi el al.75 2015 | 17 | Range 17-76 years (average 29 years) | M 7 F 10 | Proximal phalanx 10, middle phalanx 4, metacarpal bone 3 | Surgical resection and autogenous bone grafting | 6 months-9 years (average 4 years and 2 months) | No recurrence |

| IE. | Sharma et al.76 2014 | 31 | Range: 5-59 (mean 20.6±13.2 years) | M 25 F 6 | Femur 12, tibia 11, calcaneus 1, humerus 1. Vertebrae (lumbar 1, cervical 1). No bony lesion could be identified on SPECT/CT in 4 patients | NA | Range 6-36 months | NA |

| 19. | Bourgauli etal.11 2014 | 87 | Range 5-19 (mean 23) | M 63 F 24 | Femur 27, tibia in 18, femoral neck 18, and ta lus in 6 cases. Greater trochanter 3, elbow, knee, humerus and scapula in 2 patients each; spine, fibula, Lateral cuneiform, metatarsal, cuboid, calcaneus and pelvis in one patient each | Percutaneous CT guided radiofrequency thermocoagulation | Range 6-96 (mean 34 months) | Recurrence in 9 patients |

| 20. | Raux et al.78 2014 | 44 | Range 4-34 (average age 12.7 years) | M 24 F 20 | Femoral neck 26, Lesser trochanter 18 | CT-guided percutaneous bone resection and drilling (PBRD) | Range 12-56 (mean 12 months) | Recurrence in 7 out of 42 cases with follow up |

| 21. | Rehnitz el al.79 2013 | 72 | Range 3-68 (median 18) | M 47 F 25 | Femur 26, Tibia 24, Humerus 7, Spine 4, Hip 3, Radius, fibula, calcaneus 2 cases each, Scapula and talus 1 case each | CT-guided RFA | Range 3-109 months (mean, 51.2±31.2 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 22. | Etienne et al.80 2013 | 35 | 3 to 69 years (mean: 21.7 years) | M 27 F 8 | Femur 19, tibia 7, patella 2, ulna, iliac bone, sacrum, calcaneus, neck of the talus, humerus and lateral cuneiform bone 1 case each | Interstitial laser photocoagulation | Range 3-122 months (mean 40 months) | Recurrence in 2 patients |

| 23. | Jafari et al.81 2013 | 25 | 16 to 46 years (average 25.2±7.6 years) | M 21 F 4 | Proximal phalanx 10, distal phalanx 5, metacarpal 4, scaphoid and capitate 2 in each, styloid of radius and trapezium 1 case each | Surgical excision 21, curettage and bone grafting 4 | Range 3 months to 8 years (mean 36.6±46.9 months) | Recurrence in 5 patients |

| 24. | Farzan et al.82 2013 | 25 | Range 12 to 48 years (mean 27.5±8.6) | M 12 F 13 | Phalanx 16, metacarpal 4, carpal 4, distal radius 1 | Surgical excision and currettage | Mean 98 months | Recurrence in 3 patients |

| 25. | Reverie-Vinaixa el al.83 2013 | 54 | Range 10-47 years (mean 22.7 years) | M 46 F 8 | Femur 28, tibia 15, humerus 5, fibula 2, talus 2, and ulnar 2 | Percutaneous CT-guided resection | Range 6-2S months (mean 22 months) | Recurrence in 4 patients |

| 26. | Earhart et al.84 2013 | 21 | Range 2.5-28.6 years (mean 11.4 years) | M 16 F 6 | Proximal femur 10, tibial shaft 3, Femoral shaft 2, distal femur 2, distal tibia 2, distal humerus 1, calcaneus 1 | Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation | Range 0.5-86.1 months (average 17.0 months) | No recurrence in 17 patients with follow up |

| 27. | Villani et al.85 2013 | 53 | Mean age 7.2 years | M 40 F 13 | Tibia 22, femur 14, pelvis 5, talus 3, humerus 2, sacrum 2, heel 1, radius 2, patella l, rib 1 | Radiofrequency ablation | Follow up at 6, 18 and 24 months | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 28. | Rehnitz el al.87 2012 | 77* | Range 3-68 (mean 17) | M 52 F 25 | Femur 27, Tibia 25, Humerus 8, Spine 6, Hip 3, Radius, Scapula, and Fibula 2 in each case; Calcaneus and Talus 1 in each case | CT-guided radiofrequency ablation | Range 3-92 months (mean 38.5 months) | Primary success rate was 74/77 (96.1%) of all patients. Retreatment with RFA in 3 patients |

| 29. | Neumann et at.87 2012 | 33 | Range 5-50 years (mean 20 years) | M 22 F 11 | NA | CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermoablation | Range, 60-121 months (mean 92 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 30. | Marić el al.88 2011 | 19 | All younger tha 18 years. Average | M 13 F 6 | Femur 10, Tibia 7, Fibula 1, Metatarsal 1 | Fluoroscopic guided percutaneous excision 14 | NA | NA |

| age 12.36=3.64 | Excision by resection 5 | |||||||

| 31. | Mahnken et el.89 2011 | 17 | Range 9-49 years (mean 24.8 years) | M 12 F 5 | Femur 11, tibia 4, fibula 1, cuboid bone 1 | CT-guided radio frequency ablation | Range 4 to 47 months (mean 29.9±14.8) | Recurrence in 3 patients |

| 32. | Mylona et al.90 2010 | 23 | Range 15 to 38 years (mean age 28.04±6.72 years) | M 19 F 4 | Femoral diaphysis 5, Tibial diaphysis 4, Inferior articular surface of femur 2, Superior articular surface of tibia 1, Inferior articular surface of tibia 3, Anterior column of acetabulum 1, Sacrum 2, Vertebral arc 1, Transverse process 1, Great trochanter 2 | CT-guided laser interstitial thermal therapy | Last follow up 12 mouths | Recurrence in 2 patients |

| 33. | Akhlaghpoor et al.91 2010 | 21 | Range 10-30 years (mean 19 years) | M 17 F 4 | Talus 8, Humerus 3, Acetabulum 3, Scapula (acromion) 1, Scapula (neck) 1, Ulna (radioulnar joint) 1, Third proximal phalanx 1, cuneiform 1, vertebra 2 | Radiofrequency ablation | Range 12-37 months (mean 27.8 months) | No recurrence |

| 34. | von Kalle et al.92 2009 | 54 | Range 1.4-38.8 years (median 10.3 years) | M 35 F 19 | Femur 28, tibia 15, pedicles of the thoracolumbar spine 5, calcaneus 3, humerus 2, acetabulum 1 | en bloc resection, open drill excision or curettage | NA | NA |

| 35. | Sung et at.93 2009 | 28 | Range 7-55 years (24.5 years) | M 21 F 7 | Femur 18, Tibia 6, pelvic bone 2, 1 each in the humerus and the fibula | CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermoablation (PRT) | Range 24-66 months (meau 41.1 months) | Recurrence in 5 patients |

| 36. | Peyser et al.94 2009 | 22 | Range 3.6 to 18 years (mean 13.6 months) | M 15 F 7 | Femur 15, Tibia 2, Humerus, talus, calcaneus, second metatarsus, and sacrum 1 case each | CT-Quided RFA utilizing a water-cooled tip | Range 16-66 months (average 38.5 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 37. | Blaskiewicz el at.95 2009 | 20 | Range 6-18 years (mean 13 years). | M 8 F 12 | Cervical spine 7, thoracic spine 7, lumbar spine 5, sacrum 1 | Intraoperative bone scans (IOBSs) assisted resection | Range of 8-156 mouths (average 156 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 38. | Zampa et al.96 2009 | 19 | Range 13-7 years (meau 29.8=12.2 Years) | M 14 F 5 | Femur 9, Tibia 3, Vertebra 3, Calcaneum 2, Acetabulum 1, Ilium 1 | NA | NA | NA |

| 39. | Aschero et al.97 2009 | 25 | Range 4 to 17 years (average 11.5 years) | M 15 F 10 | Femur 12,tibia 9, acetabulum2, ilium 1, talus 1 | CT-guided laser thermocoagulation | Range 3 to 61 months (mean 26 months). | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 40. | Vanderschueren et al.98 2009 | 24 | Range 7-55 years (mean 23 years) | M 16 F 8 | Thoracic spine 10, Lumbar spine 7, Cervical spine 3, sacrum 4 | Radiofrequency ablation | Range 9-142 mouths (mean 72 months) | Recurrence in 5 patients |

| 41. | Lee et al.99 2007 | 16 | Range 13-51 years (meau age 23.2 years) | M 1l F 5 | Femur 12, pelvis 2, tibia 1,humerus 1 | Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation | Range 2-17 months (mean 5.3 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 42. | Akhlaghpoor et al.100 2007 | 54 | Range 3 to 26 years (mean 15.4±5.6 years) | M 43 F ll | Femoral shaft 25, femoral neck 17, tibia 10, fibula 1, L3 vertebra 1 body 1 | Combination of radiofrequency ablation and alcohol ablation | Range 13 to 48 months (28.2±7.4 months) | Recurrence in 2 patients |

| 43. | Yang et al.101 2007 | 23 | Range 6 to 39 years (meau 13.8 years) | M 11 F 9 | Proximal femur 11, Femoral diaphysis 3, Distal femur 1, Proximal tibia 2, Tibial diaphysis 1, Distal tibia 1, Talar neck 1, Proximal humerus, distal radius and capitate 1 case each | Conventional open excision 20 patients CT-guided mini-incision surgery 6 patients | Range 3 weeks to 142 months (mean 42.7 months) | Recurrence rate for conventional surgery 23%; CT-guided mini-incision surgery 0% |

| 44. | Vanderschueren et al.102 2007 | 97 | NA | NA | Femur 42, Tibia 14, Pelvis 8, Talus 5, Humerus 4, Ulna 4, Carpus 4, Metacarpal 3, Lumbar spine 3, Tarsal 3, Fibula 2, Cervical spine 2, Thoracic spine, Radius and Phalanx 1 case each | Thermocoagulation | Range 5-81 months (mean 41 months) | Unsuccessful treatment iu 23 patients |

| 45. | Gangi et al.103 2007 | 114 | Range 5-56 years (meau 22.3 years) | M 69 F 45 | Femur 48, tibia 19, humerus 8, fibula 2, spine 12, acetabulum 5, talus 4, calcaneus 3, ilium, navicular bone and metacarpal bone 2 cases each, ulna, coracoid process of scapula, acromion, lunate bone, hamate bone, cuneiform bone, and posterior sixth rib 1 case each | Percutaneous interstitial Laser ablation | Range 13-130 months (mean 58.5 months) | Recurrence in 6 patients |

| 46. | Peyser etal.104 2007 | 51 | Range 3.5-57 years (mean 20 years) | M 36 F 15 | Femur (29), tibia (10), calcaneus (2), talus (2), metatarsus (2),hu|nerus (1), sacrum (1), scapula (1), olecranon (1), patella (1) and thoracic vertebra (1) | CT-guided RFA using the water-cooled probe | Range 9-51 months (mean 2 years) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 47. | Fenichel et al.105 2006 | 18 | Range 11 to 35 years (mean 18 years) | M 4 F 14 | Proximal femur 7, femoral shaft 3, tibia 5, Iliac bone 1, sacrum 1, acetabular roof 1 | Percutaneous CT-guided curettage | Range 12 to 42 months (average 29 months) | Recurrence in 2 patients |

| 48. | Sierre et al.106 2006 | 18 | Range 6-17 years (mean 11.6 years) | M 11 F 7 | Femur 10, tibia 5, humerus 2, vertebral body 1 | CT-guided drilling resection | Range 2-60 months (mean 19.4 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 49. | Kjar et al.107 2006 | 24 | Range 10-51 years (median 20 years) | M 18 F 6 | Femur 12, tibia 10, 1 each in the humerus and fibula | Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation | Range 2-56 months (median 26 months) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 50. | Cribb et al.108 2005 | 45 | Average age 21 years | M 32 F 13 | Femoral neck 12, femoral diaphysis 8, proximal femur 4, tibial diapbysis 11, distal tibia 1, proximal humerus 1, ulna diaphysis 2, index finger proximal phalanx diapbysis 1, talus 2, calcaneum 1, acetabulum l,one in S1 | CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermocoagulation | Range 12-48 months (mean 26 months) | Recurrence in 7 patients |

| 51. | Martel et al.109 2005 | 41 | Range 5-43 years (mean 18.7 years) | M 27 F 14 | Femur 14, tibia 5, foot 5, spine 5, fibula 3, acetabulum 2, humerus 2, clavicle, hand, astragalus, iliacus and scapula 1 in each | CT-guided percutaneous RFA 38 patients Surgery 3 patients | Range 3 months to 2 years | Recurrence in 4 patients |

| 52. | Rimondi et al.110 2005 | 97 | Range 4-47 years (mean 20 years) | M 61 F 36 | Femur 44, Tibia 21, Humerus 3, Acetabulum 5, Ulna 4, Radius 3, Fibula 2, Ankle 1, Patella 1, Ischium 1, Cuneiforms 1, Tarsal scafoid 1 | Radiofrequency thermoablation | 1 year for 74 patients, 6 months for 16 patients, and 3 months for 7 patients | Recurrence in 15 patients |

| 53. | Cioni et al.111 2004 | 38 | Range 4-46 years (mean 23±1 1.9 years) | M 31 F 7 | Femur head 4, Femur neck 9, Trochanter minor 6, Femur diaphysis 6, Tibia 7, Radius 3, Fibula 1, Calcaneus 2, Ilium bone 1 | CT-guided percutaneous RFA | Range 12-66 months (mean 35.5±7.5 months) | Recurrence in 8 patients |

| 54. | Bisbinas et al.112 2004 | 38 | Range 19-30 years (mean 21.5 years) | All males | Lower limb bone 32, upper limb 2, spinal 4 | Open wide excision | Range 1-5.5 years (mean 2.2 years) | Recurrence in 1 patient |

| 55. | Albisinni et al.113 2004 | 183 | NA | NA | NA | Radiofrequency thermal ablation | Range 1-40 months | Recurrence in 2 patients |

| 56. | Woertler et al.114 2001 | 47 | Range 8-41 years (mean 19.6 years) | M 34 F 13 | Femur 25, tibia 15, pelvis 2, humerus 1, ulna 1, talus 1, calcaneus 5, vertebral body 5 | CT-guided radiofrequency ablation | Range S-39 months (mean 22 months) | Recurrence in 3 patients |

| 57. | Sans et al.115 1999 | 38 | Range 5-64 years (mean 23.4 years) | M 29 F 9 | Femur 17, tibia 12, fibula, acetabulum, talus, patella, iliac wing 1 case each, spine 2, ulna 1, radius 1 | CT-guided percutaneous resection | Mean follow up 17 years | Recurrence in 6 patients |

| 58. | Rosenthal et al.117 1998 | 125 | Average age 22 and 23 years for operative and ablation group respectively | M 83 F 37 | NA | Radiofrequency Coagulation 38 Operative excision 87 | NA | Recurrence in 11 patients overall |

| 59. | Nogués ei al. 117 1998 | 28 | Range 7-39 years (mean 19.4 years) | M 19 F9 | Femur 12, tibia 6, fibula, talus, humerus 2 cases each, 1 case in the patella, sacrum, a dorsal vertebra, andtarsal scaphoid | NA | NA | NA |

| 60. | Loizaga et al.118 1993 | 73 | Range 2 to 51 years (mean 12 years) | M 46 F 27 | Long bones of lower extremities 51.5%, Foot 15,6%, Eland 17%, Upper extremities 6.33%, Vertebral column 6.25%, Thorax 3,2%, Lower extremities 68.51%, Foot and hand 32.62%, Four extremities 93% | NA | NA | NA |

References

- 1.Greenspan A. Benign bone-forming lesions: osteoma, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastoma. Skelet Radiol 1993;22:485-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe HL. Osteoid-osteoma: a benign osteoblastic tumor composed of osteoid and atypical bone. Archiv Surg 1935;31:709-28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee EH, Shafi M, Hui JH. Osteoid osteoma: a current review. J Pediatr Orthop 2006;26:695-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitsoulis P, Mantellos G, Vlychou M. Osteoid osteoma. Acta Orthop Belg 2006;72:119-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward WG, Eckardt JJ, Shayestehfar S, et al. Osteoid osteoma diagnosis and management with low morbidity. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;291:229-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghanem I. The management of osteoid osteoma: updates and controversies. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006;18:36-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boscainos PJ, Cousins GR, Kulshreshtha R, et al. Osteoid osteoma. Orthopedics 2013;36:792-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mungo DV, Zhang X, O’Keefe RJ, et al. COX-1 and COX-2 expression in osteoid osteomas. J Orthop Res 2002;20:159-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasegawa T, Hirose T, Sakamoto R, et al. Mechanism of pain in osteoid osteomas: an immunohistochemical study. Histopathology 1993;22:487-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulman L, Dorfman HD. Nerve fibers in osteoid osteoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:1351-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baruffi M, Volpon J, Neto JB, Casartelli C. Osteoid osteomas with chromosome alterations involving 22q. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2001;124:127-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhusnurmath S, Hoch B. Benign boneforming tumors: Approach to diagnosis and current understanding of pathogenesis. Surg Pathol Clin 2012;5:101-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Paris: Iarc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akhlaghpoor S, Ahari AA, Ahmadi SA, et al. Histological evaluation of drill fragments obtained during osteoid osteoma radiofrequency ablation. Skelet Radiol 2010;39:451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connell JX, Nanthakumar SS, Nielsen GP, Rosenberg AE. Osteoid osteoma: the uniquely innervated bone tumor. Modern Pathol 1998;11:175-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dancer JY, Henry SP, Bondaruk J, et al. Expression of master regulatory genes controlling skeletal development in benign cartilage and bone forming tumors. Hum Pathol 2010;41:1788-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gitelis S, Schajowicz F. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma. Orthop Clini N Am 1989;20:313-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laurence N, Epelman M, Markowitz RI, et al. Osteoid osteomas: a pain in the night diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol 2012;42:1490-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chai JW, Hong SH, Choi J-Y, et al. Radiologic Diagnosis of Osteoid Osteoma: From Simple to Challenging Findings 1. Radiographics 2010;30:737-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies AM, Sundaram M, James SJ. Imaging of bone tumors and tumor-like lesions: techniques and applications. Springer Science and Business Media; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kransdorf MJ, Stull M, Gilkey F, Moser Jr R. Osteoid osteoma. Radiographics 1991;11:671-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JH, Pahk K, Kim S, et al. Radionuclide imaging in the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. Oncol Lett 2015;10:1131-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Touraine S, Emerich L, Bisseret D, et al. Is pain duration associated with morphologic changes of osteoid osteomas at CT? Radiology 2014;271:795-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine E, Neff J. Dynamic computed tomography scanning of benign bone lesions: preliminary results. Skelet Radiol 1983;9:238-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGrath BE, Bush CH, Nelson TE, Scarborough MT. Evaluation of suspected osteoid osteoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;327:247-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinto CH, Taminiau AH, Vanderschueren GM, et al. Technical considerations in CT-guided radiofrequency thermal ablation of osteoid osteoma: tricks of the trade. Am J Roentgenol 2002;179:1633-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells RG, Miller JH, Sty JR. Scintigraphic patterns in osteoid osteoma and spondylolysis. Clin Nucl Med 1987;12:39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helms CA. Osteoid Osteoma: The Double Density Sign. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;222:167-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roach P, Connolly L, Zurakowski D, Treves S. Osteoid osteoma: comparative utility of high-resolution planar and pinhole magnification scintigraphy. Pediatr Radiol 1996;26:222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imperiale A, Moser T, Ben-Sellem D, et al. Osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma: morphofunctional characterization by MRI and dynamic F-18 FDG PET/CT before and after radiofrequency ablation. Clin Nucl Med 2009;34:184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farid K, El-Deeb G, Vigneron NC. SPECT-CT improves scintigraphic accuracy of osteoid osteoma diagnosis. Clin Nucl Med 2010;35:170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banzo I, Hernandez-Allende R, Quirce R, Carril JM. Bone SPECT in an osteoid osteoma of transverse process of first lumbar vertebra. Clin Nucl Med 2005;30:28-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan P, Fogelman I. Bone SPECT in osteoid osteoma of the vertebral lamina. Clin Nucl Med 1994;19:144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castello A, Lopci E. Incidental identification of osteoid osteoma by 68Ga- PSMA PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carra BJ, Chen DC, Bui-Mansfield LT. The Half-Moon Sign of the Femoral Neck Is Nonspecific for the Diagnosis of Osteoid Osteoma. Am J Roentgenol 2016;206:W54-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hachem K, Haddad S, Aoun N, et al. MRI in the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. J Radiol 1997;78:635-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spouge AR, Thain LM. Osteoid osteoma: MR imaging revisited. Clin Imag 2000;24:19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies M, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Davies MA, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of MR imaging in osteoid osteoma. Skelet Radiol 2002;31:559-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Assoun J, Richardi G, Railhac J-J, et al. Osteoid osteoma: MR imaging versus CT. Radiology 1994;191:217-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moberg E. The natural course of osteoid osteoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1951;33:166-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golding JS. The natural history of osteoid osteoma: with a report of twenty cases. J Bone Joint Surg 1954;36:218-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bottner F, Roedl R, Wortler K, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor for pain management in osteoid osteoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;393:258-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carpintero-Benitez P, Aguirre MA, Serrano JA, Lluch M. Effect of rofecoxib on pain caused by osteoid osteoma. Orthopedics 2004;27:1188-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruneau M, Polivka M, Cornelius JF, George B. Progression of an osteoid osteoma to an osteoblastoma: case report. J Neurosurg Spine 2005;3:238-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frassica FJ, Waltrip RL, Sponseller PD, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma in children and adolescents. Orthop Clin N Am 1996;27:559-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atesok KI, Alman BA, Schemitsch EH, et al. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011;19:678-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Towbin R, Kaye R, Meza M, et al. Osteoid osteoma: percutaneous excision using a CT-guided coaxial technique. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:945-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Assoun J, Railhac J, Bonnevialle P, et al. Osteoid osteoma: percutaneous resection with CT guidance. Radiology 1993;188:541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roger B, Bellin M-F, Wioland M, Grenier P. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided percutaneous excision confirmed with immediate follow-up scintigraphy in 16 outpatients. Radiology 1996;201:239-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mazoyer J-F, Kohler R, Bossard D. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided percutaneous treatment. Radiology 1991;181:269-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lenke LG, Sutherland CJ, Gilula LA. Osteoid osteoma of the proximal femur: CT-guided preoperative localization. Orthopedics 1994;17:289-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sans N, Galy-Fourcade D, Assoun J, et al. Osteoid Osteoma: CT-guided Percutaneous Resection and Follow-up in 38 Patients 1. Radiology 1999;212:687-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muscolo DL, Velun O, Acero GP, et al. Osteoid Osteoma of the Hip: Percutaneous Resection Guided by Computed Tomography. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995;310:170-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roqueplan F, Porcher R, Hamzé B, et al. Long-term results of percutaneous resection and interstitial laser ablation of osteoid osteomas. Eur Radiol 2010;20:209-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Berg JC, Pattynama PM, Obermann WR, et al. Percutaneous computedtomography- guided thermocoagulation for osteoid osteomas. Lancet 1995;346:350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoffmann R-T, Jakobs TF, Kubisch CH, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of osteoid osteoma-5- year experience. Eur J Radiol 2010;73:374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Papathanassiou ZG, Petsas T, Papachristou D, Megas P. Radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteomas: five years experience. Acta Orthop Belg 2011;77:827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenthal DI, Hornicek FJ, Torriani M, et al. Osteoid Osteoma: Percutaneous Treatment with Radiofrequency Energy 1. Radiology 2003;229:171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bousson V, Leturcq T, Ea H-K, et al. An open-label, prospective, observational study of the efficacy of bisphosphonate therapy for painful osteoid osteoma. Eur Radiol 2018;28:478-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santiago E, Pauly V, Brun G, et al. Percutaneous cryoablation for the treatment of osteoid osteoma in the adult population. Eur Radiol 2018:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nijland H, Gerbers J, Bulstra S, et al. Evaluation of accuracy and precision of CT-guidance in Radiofrequency Ablation for osteoid osteoma in 86 patients. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu H, Lu C, Chen M. Evaluation of minimally invasive laser ablation in children with osteoid osteoma. Oncol Lett 2017;13:155-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shields DW, Sohrabi S, Crane EO, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for osteoid osteoma-Recurrence rates and predictive factors. Surgeon 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quraishi NA, Boriani S, Sabou S, et al. A multicenter cohort study of spinal osteoid osteomas: results of surgical treatment and analysis of local recurrence. Spine J 2017;17:401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Erol B, Topkar MO, Tokyay A, et al. Minimal invasive intralesional excision of extremity-located osteoid osteomas in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2017;26:552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garge S, Keshava SN, Moses V, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteoma in common and technically challenging locations in pediatric population. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2017;27:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karagöz E, Özel D, Özkan F, et al. Effectiveness of computed tomography guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation therapy for osteoid osteoma: initial results and review of the literature. Polish J Radiol 2016;81:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miyazaki M, Arai Y, Myoui A, et al. Phase I/II multi-institutional study of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for painful osteoid osteoma (JIVROSG-0704). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2016;39:1464-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Masciocchi C, Zugaro L, Arrigoni F, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound surgery for minimally invasive treatment of osteoid osteoma: a propensity score matching study. Eur Radiol 2016;26:2472-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wallace AN, Tomasian A, Chang RO, Jennings JW. Treatment of osteoid osteomas using a navigational bipolar radiofrequency ablation system. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2016;39:768-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Outani H, Hamada K, Takenaka S, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteoma using a three-dimensional navigation system. J Orthop Sci 2016;21:678-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Etemadifar MR, Hadi A. Clinical findings and results of surgical resection in 19 cases of spinal osteoid osteoma. Asian Spine J 2015;9:386-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Petrilli M, Senerchia AA, Petrilli AS, et al. Computed tomography-guided percutaneous trephine removal of the nidus in osteoid osteoma patients: experience of a single center in Brazil. Radiol Brasil 2015;48:211-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Knudsen M, Riishede A, Lucke A, et al. Computed tomography-guided radiofrequency ablation is a safe and effective treatment of osteoid osteoma located outside the spine. Dan Med J 2015;62:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamdi M, Tarhouni L, Daghfous M, et al. Osteoid osteoma of the phalanx and metacarpal bone: report of 17 cases. Musculoskel Surg 2015;99:61-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sharma P, Mukherjee A, Karunanithi S, et al. 99mTc-Methylene diphosphonate SPECT/CT as the one-stop imaging modality for the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. Nucl Med Commun 2014;35:876-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bourgault C, Vervoort T, Szymanski C, et al. Percutaneous CT-guided radiofrequency thermocoagulation in the treatment of osteoid osteoma: a 87 patient series. Orthopaed Traumatol Surg Res 2014;100:323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raux S, Abelin-Genevois K, Canterino I, et al. Osteoid osteoma of the proximal femur: treatment by percutaneous bone resection and drilling (PBRD). A report of 44 cases. Orthopaed Traumatol Surg Res 2014;100:641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rehnitz C, Sprengel SD, Lehner B, et al. CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteoma: correlation of clinical outcome and imaging features. Diagn Intervent Radiol 2013;19:330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Etienne A, Waynberger É, Druon J. Interstitial laser photocoagulation for the treatment of osteoid osteoma: retrospective study on 35 cases. Diagn Intervent Imaging 2013;94:300-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jafari D, Shariatzade H, Mazhar FN, et al. Osteoid osteoma of the hand and wrist: a report of 25 cases. Med J Islam Rep Iran 2013;27:62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farzan M, Ahangar P, Mazoochy H, Ardakani MV. Osseous tumours of the hand: a review of 99 cases in 20 years. Archiv Bone Joint Surg 2013;1:68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reverte-Vinaixa MM, Velez R, Alvarez S, et al. Percutaneous computed tomography-guided resection of non-spinal osteoid osteomas in 54 patients and review of the literature. Archiv Orthop Trauma Surg 2013;133:449-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Earhart J, Wellman D, Donaldson J, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of osteoid osteoma: results and complications. Pediatr Radiol 2013;43:814-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Villani MF, Falappa P, Pizzoferro M, et al. Role of three-phase bone scintigraphy in paediatric osteoid osteoma eligible for radiofrequency ablation. Nucl Med Commun 2013;34:638-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rehnitz C, Sprengel SD, Lehner B, et al. CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma: clinical success and long-term follow up in 77 patients. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:3426-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Neumann D, Berka H, Dorn U, et al. Follow-up of thirty-three computedtomography- guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermoablations of osteoid osteoma. Int Orthop 2012;36:811-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maric D, Djan I, Petkovic L, et al. Osteoid osteoma: fluoroscopic guided percutaneous excision technique-our experience. J Pediatr Orthop B 2011;20:46-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mahnken AH, Bruners P, Delbrück H, Günther RW. Radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteoma: initial experience with a new monopolar ablation device. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2011;34:579-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mylona S, Patsoura S, Galani P, et al. Osteoid osteomas in common and in technically challenging locations treated with computed tomography-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation. Skelet Radiol 2010;39:443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Akhlaghpoor S, Ahari AA, Shabestari AA, Alinaghizadeh MR. Radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteoma in atypical locations: a case series. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:1963-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Von Kalle T, Langendörfer M, Fernandez F, Winkler P. Combined dynamic contrast-enhancement and serial 3D-subtraction analysis in magnetic resonance imaging of osteoid osteomas. Eur Radiol 2009;19:2508-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sung K-S, Seo J-G, Shim JS, Lee YS. Computed-tomography-guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermoablation for the treatment of osteoid osteoma-2 to 5 years follow-up. Int Orthop 2009;33:215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peyser A, Applbaum Y, Simanovsky N, et al. CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of pediatric osteoid osteoma utilizing a water-cooled tip. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:2856-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Blaskiewicz DJ, Sure DR, Hedequist DJ, et al. Osteoid osteomas: intraoperative bone scan-assisted resection. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2009;4:237-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zampa V, Bargellini I, Ortori S, et al. Osteoid osteoma in atypical locations: the added value of dynamic gadolinium- enhanced MR imaging. Eur J Radiol 2009;71:527-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aschero A, Gorincour G, Glard Y, et al. Percutaneous treatment of osteoid osteoma by laser thermocoagulation under computed tomography guidance in pediatric patients. Eur Radiol 2009;19:679-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vanderschueren GM, Obermann WR, Dijkstra SP, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of spinal osteoid osteoma: clinical outcome. Spine 2009;34:901-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee MH, Ahn JM, Chung HW, et al. Osteoid osteoma treated with percutaneous radiofrequency ablation: MR imaging follow-up. Eur J Radiol 2007;64:309-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Akhlaghpoor S, Tomasian A, Shabestari AA, Ebrahimi M, Alinaghizadeh M. Percutaneous osteoid osteoma treatment with combination of radiofrequency and alcohol ablation. Clin Radiol 2007;62:268-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang W-T, Chen W-M, Wang N-H, Chen T-H. Surgical treatment for osteoid osteoma-experience in both conventional open excision and CTguided mini-incision surgery. J Chinese Med Assoc 2007;70:545-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vanderschueren GM, Taminiau AH, Obermann WR, et al. The healing pattern of osteoid osteomas on computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging after thermocoagulation. Skelet Radiol 2007;36:813-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gangi A, Alizadeh H, Wong L, et al. Osteoid osteoma: percutaneous laser ablation and follow-up in 114 patients. Radiology 2007;242:293-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peyser A, Applbaum Y, Khoury A, et al. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided radiofrequency ablation using a watercooled probe. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fenichel I, Garniack A, Morag B, et al. Percutaneous CT-guided curettage of osteoid osteoma with histological confirmation: a retrospective study and review of the literature. Int Orthop 2006;30:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sierre S, Innocenti S, Lipsich J, et al. Percutaneous treatment of osteoid osteoma by CT-guided drilling resection in pediatric patients. Pediatr Radiol 2006;36:115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kjar RA, Powell GJ, Schilcht SM, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for osteoid osteoma: experience with a new treatment. Med J Austral 2006;184:563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cribb G, Goude W, Cool P, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency thermocoagulation of osteoid osteomas: factors affecting therapeutic outcome. Skelet Radiol 2005;34:702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Martel J, Bueno Á, Ortiz E. Percutaneous radiofrequency treatment of osteoid osteoma using cool-tip electrodes. Eur J Radiol 2005;56:403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rimondi E, Bianchi G, Malaguti M, et al. Radiofrequency thermoablation of primary non-spinal osteoid osteoma: optimization of the procedure. Eur Radiol 2005;15:1393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cioni R, Armillotta N, Bargellini I, et al. CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteoma: long-term results. Eur Radiol 2004;14:1203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bisbinas I, Georgiannos D, Karanasos T. Wide surgical excision for osteoid osteoma. Should it be the first-choice treatment? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2004;14:151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Albisinni U, Rimondi E, Bianchi G, Mercuri M. Experience of the Rizzoli Institute in radiofrequency thermal ablation of musculoskeletal lesions. J Chemother 2004;16:75-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Woertler K, Vestring T, Boettner F, et al. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation and follow-up in 47 patients. J Vasc Intervent Radiol 2001;12:717-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sans N, Galy-Fourcade D, Assoun J, et al. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided percutaneous resection and follow-up in 38 patients. Radiology 1999;212:687-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rosenthal DI, Hornicek FJ, Wolfe MW, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency coagulation of osteoid osteoma compared with operative treatment. JBJS 1998;80:815-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nogues P, Marti-Bonmati L, Aparisi F, et al. MR imaging assessment of juxta cortical edema in osteoid osteoma in 28 patients. Eur Radiol 1998;8:236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Loizaga J, Calvo M, Barea FL, et al. Osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma: clinical and morphological features of 162 cases. Pathol-Res Pract 1993;189:33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]