Abstract

Key points

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a genetic condition that is the most common form of inherited intellectual impairment and causes a range of neurodevelopmental complications including learning disabilities and intellectual disability and shares many characteristics with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

In the FXS mouse model, Fmr1−/y, impaired synaptic plasticity was restored by pharmacologically inhibiting GluN2A‐containing NMDA receptors but not GluN2B‐containing receptors.

Similar results were obtained by crossing Fmr1−/y with GluN2A knock‐out (Grin2A−/−) mice.

These results suggest that dampening the elevated levels of GluN2A‐containing NMDA receptors in Fmr1−/y mice has the potential to restore hyperexcitability of the neural circuitry to (a more) normal‐like level of brain activity.

Abstract

NMDA receptors (NMDARs) play important roles in synaptic plasticity at central excitatory synapses, and dysregulation of their function may lead to severe disorders such Fragile X syndrome (FXS). FXS is caused by transcriptional silencing of the FMR1 gene followed by lack of the encoding protein. Here we examined the effects of pharmacological and genetic manipulation of hippocampal NMDAR functions in long‐term potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD). We found impaired NMDAR‐dependent LTP in the Fmr1‐deficient mice, which could be fully restored when GluN2A‐containing NMDARs was pharmacological inhibited. Interestingly, similar LTP effects were observed when the GluN2A gene (Grin2a) was deleted in Fmr1−/y mice (Fmr1−/y/Grin2a−/− double knockout). In addition, GluN2A inhibition improved elevated mGluR5‐dependent LTD to normal level in the Fmr1−/y mouse. These findings suggest that GluN2A is a promising target in FXS research that could help us better understand the disorder.

Keywords: Fragile X syndrome, Glutamate receptors, GluN2A, Synaptic plasticity, tri‐heteromeric NMDA receptors, Intellectual Disability, Developmental Disability, Autism, neuropsychiatric diseases

Key points

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a genetic condition that is the most common form of inherited intellectual impairment and causes a range of neurodevelopmental complications including learning disabilities and intellectual disability and shares many characteristics with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

In the FXS mouse model, Fmr1−/y, impaired synaptic plasticity was restored by pharmacologically inhibiting GluN2A‐containing NMDA receptors but not GluN2B‐containing receptors.

Similar results were obtained by crossing Fmr1−/y with GluN2A knock‐out (Grin2A−/−) mice.

These results suggest that dampening the elevated levels of GluN2A‐containing NMDA receptors in Fmr1−/y mice has the potential to restore hyperexcitability of the neural circuitry to (a more) normal‐like level of brain activity.

Introduction

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a genetic condition that is the most common form of inherited intellectual impairment. FXS causes a range of neurodevelopmental complications including learning disabilities and intellectual disability and shares many characteristics with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), being one of the leading single‐gene causes of ASD (Jacquemont et al. 2007). The syndrome is caused by a genetic disorder linked to the X chromosome and, due to this association, it has a higher frequency in males than in females (Turner et al. 1996; Fisch et al. 2002; Coffee et al. 2009). The most common form of the disorder is caused by an irregular expansion of a CGG trinucleotide repeat in the gene responsible for FXS, the so‐called fragile X mental retardation‐1 (FMR‐1) gene (Verkerk et al. 1991). This expansion leads to silenced transcription of the FMR‐1 gene, resulting in lack of the encoded protein, fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP). This leads to abnormal brain development and cognitive dysfunctions, causing a developmental delay typically resulting in patients with an IQ value below 70 (Hagerman, 1996). Other associated phenotypic abnormalities include behavioural symptoms such as anxiety, social avoidance, attention problems and aggression, and in the most severe cases, autism.

The FXS mouse model, the Fmr‐1 knock‐out (Fmr1−/y) mouse, which lacks expression of FMRP, displays phenotypes similar to those observed in humans with FXS including enlarged testes, impaired cognitive function (including learning disabilities), disrupted memory, repetitive behaviours, seizure susceptibility and abnormal dendritic spines characterized as being long, thin and immature (The Dutch‐Belgian Fragile X Consortium, 1994; Chen & Toth, 2001; Nimchinsky et al. 2001; Yan et al. 2004, 2005; Lewis et al. 2007; Spencer et al. 2011; Boda et al. 2014; Bostrom et al. 2016). Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests that lack of FMRP plays an important role in synaptic plasticity (Sidorov et al. 2013), which probably represents the cellular basis for learning and memory (Neves et al. 2008).

Multiple labs have reported increased hippocampal metabotropic glutamate receptor (group 1)‐mediated long‐term depression (mGluR‐LTD) in the CA1 area of Fmr1−/y mice (Huber et al. 2002; Dölen & Bear, 2008; Michalon et al. 2012; Barnes et al. 2015; Toft et al. 2016; Chatterjee et al. 2018); however, this mGluR‐LTD depends strongly upon active NMDA receptors (NMDARs) in adult Fmr1−/y mice (Toft et al. 2016). On the other hand, reports of NMDAR‐dependent long‐term plasticity (LTP) in Fmr1−/y mice have been less clear. Several reports have documented impaired LTP in different brain regions (Godfraind et al. 1996; Paradee et al. 1999; Li et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2005; Desai et al. 2006; Meredith et al. 2007; Shang et al. 2009) including area CA1 of the hippocampus (Lauterborn et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2011). Together, these studies point toward abnormalities in NMDAR‐mediated synaptic plasticity signalling in the hippocampus of Fmr1−/y mice.

In this study, we examine the effects of inhibition of NMDAR‐specific GluN2 subunits in the hippocampus CA1 area in wild‐type (WT) and Fmr1−/y mice, and in offspring derived from mating of Fmr1−/y and Grin2a−/− mice. We show that impaired LTP in the CA1 depends strongly upon Schaffer collateral stimulation intensity in brain slices of Fmr1−/y mice. In addition, pharmacological or genetic blockage of GluN2A‐containing NMDARs completely rescues LTP and mGluR‐LTD in Fmr1‐deficient mice whereas the same treatment has no apparent impact on WT mice.

Experimental procedures

Ethical approval

The animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the animal care guidelines of Aarhus University, and conform to the principles and regulations as described by Grundy (2015).

Animals

We used postnatal day (P) P30–40 male Fmr1−/y mice (Fmr1tm1cgr/j; MGI:1857169; TmRRID: IMSR_JAX:003025, the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), Grin2a−/− (Grin2atm1Mim; MGI:1928285) and C57BL/6 WT mice for this study. The Fmr1−/y mouse was bred in a C57BL/6 background. Grin2atm1Mim mice were generated by Masayoshi Mishina and his group (Sakimura et al. 1995) and were back‐crossed repeatedly with C57BL/6 mice (Kiyama et al. 1998). Grin2atm1Mim mice for this study were generously provided by Dr Rolf Sprengel (Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, Germany). Animals were kept on a 12:12 h light–dark cycle with a constant room temperature; the mice were housed in groups and provided with ad libitum food and water. Six different genotypes (Grin2a−/−; Grin2a+/−; Fmr1−/y; Fmr1−/y/Grin2a−/−; Fmr1−/y/Grina+/−; WT) were successfully generated from cross‐breeding Fmr1−/y with Grin2a−/− mice.

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed using a standard PCR protocol and HotStar Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen‐Nordic, Olso, Norway). The following primers were used for Grin2a−/−: Common Forward: GCTCCCCATGGGCCTTCTTTTACC; WT Reverse: GGTTAGCCCGTTGAGTCACC; Grin2a−/− Reverse: CAGACTGCCTTGGGAAAAGCG. The Grin2a+ allele provided a 297 bp amplified fragment and the Grin2a− allele a 180 bp fragment. The following primers were used for Fmr1−/y−: Mutant Forward: CACGAGACTAGTGAGACGTG; WT Forward: TGTGATAGAATATGCAGCATGTGA; Common Reverse: CTTCTGGCACCTCCAGCTT. The amplified fragment for Fmr1+ was 131 bp and for Fmr1− 400 bp.

Slice preparation

The animals were deeply anaesthetized with isoflurane using a vaporizer and decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed and placed in ice‐cold slicing solution containing the following ACSF (in mm): 130 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 5 MgCl2 and 10 glucose, equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2 mixture, pH 7.4. Coronal slices of 300 μm were prepared with a Leica VT1200S vibrating microtome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and were incubated at room temperature for ∼1 h before being transferred to a recording chamber in the medium described above with the exception that MgCl2 was lowered to 1.5 mm and CaCl2 was raised to 2 mm. Slices in the recording chamber were allowed to rest for an additional ∼2 h before the start of recordings. To test for the involvement of excitatory inputs from CA3, in about half of the experiments (randomly selected from all genotypes), CA3 was surgically removed immediately after sectioning with no clear difference between recordings made in slices with or without a cut [average amount of LTP at timepoint 60 min after theta burst stimulation (TBS) induction: WT: 141 ± 5 (n = 21); WTcut: 138 ± 4 (n = 28); P > 0.6(data not shown)].

Experimental design and statistical analysis

Individual slices were placed in an interface tissue slice chamber (BSC2, Scientific System Design), where the temperature was maintained at 30.0 ± 0.3°C. The slices were perfused with carbogenated ACSF with a flow rate through the chamber of 2.5 ml/min set with a peristaltic pump. A bipolar stimulating electrode made from twisted nichrome wires (66 μm; A‐M Systems, Carlsborg, WA, USA) was placed on the surface of the stratum radiatum area of CA1 to orthodromically stimulate the Schaffer collateral/commissural fibres. Dendritic field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded in stratum radiatum of CA1 using a glass micropipette filled with 2 m NaCl with an electrode resistance of 4–6 MΩ. Dendritic fEPSPs were evoked with a single or paired‐pulse (interstimulus interval of 25–50 ms) stimulation with stimulation intensity of 25–150 μA yielding an fEPSP of about 50% of maximum response (Fig. 1 C). Recordings were collected every 20 s and were low‐pass filtered set at 1 kHz and amplified with a differential AC amplifier model 1700 (A‐M Systems). fEPSP slopes were measured and analysed from digitized EPSPs (NacGather 2.0, Theta Burst Corp., Irvine, CA, USA). The time scale of each experiment was adjusted to the time from onset of the stimulation protocol. For each experiment, extrapolation of at least 20 min before the stimulus baseline was used to create a post‐stimulus baseline. Data were normalized and averaged across experiments and expressed as mean ± SEM. For clarity of presentation, three data points were averaged and represented as one point in each individual experiment before the mean across experiments was calculated. Recordings from Fmr1−/y and Grin2a−/− cross‐bred mice and genotyping of the mice were performed blinded for the investigators. Drugs and/or LTD/LTP‐inducing stimuli were not applied until after a stable baseline was achieved for at least 20 min. Synaptic LTP was induced by TBS, consisting of a train of 5, 10 or 20 theta bursts (each containing four pulses at 100 Hz, with an interburst interval of 200 ms). mGluR‐dependent LTD was induced by 900 double‐pulses at 1 Hz (PP‐LFS) in the presence of dl‐2‐amino‐5‐phosphonopentanoic acid (APV) when indicated.

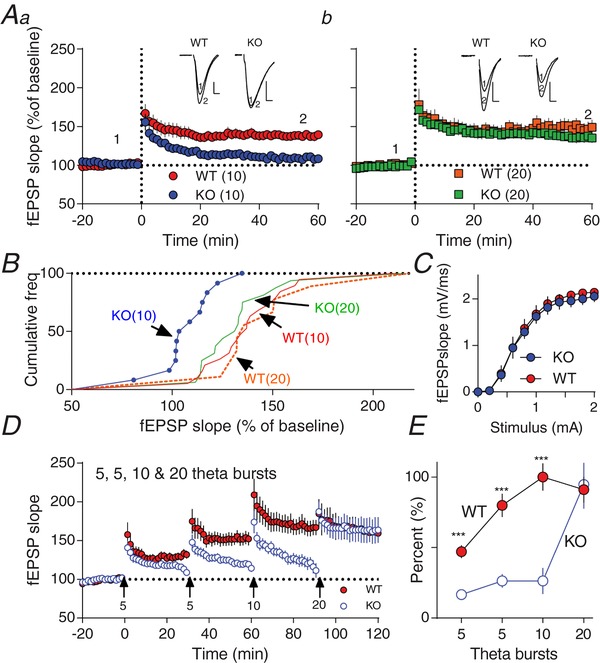

Figure 1. Impaired LTP in Fmr1−/y induced with a TBs protocol.

Aa‐b, time course of synaptic responses shown as mean fEPSP slope as a percentage of baseline. Bars represent ± SEM. At time 0, LTP was induced with 10 theta bursts (a) or 20 theta bursts (b). Inset, representative raw fEPSP traces from indicated time points. B, cumulative frequency distribution plots (%) of normalized slope (fEPSP) from A. Significant difference was observed after 60 min between Fmr1−/y (KO; 10), and WT(10), WT(20) and Fmr1−/y (KO; 20) (one‐way ANOVA‐test followed by Tukey test, F 3,52 = 6.156, P < 0.001). C, input–output curves generated from field responses (fEPSP slope; mV/ms) to single pulse stimulation of Fmr1−/y and WT. No significant difference between Fmr1−/y (KO) and WT were observed (P > 0.3; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). D, synaptic induction of LTP using trains of 5, 10 or 20 TBs. TB induction is indicated by arrows at time points 0, 30, 60 and 90 min with 5, 5, 10 and 20 theta bursts, respectively. Each trace is an average of 16 WT or 18 Fmr1−/y (KO) consecutive traces. Bars represent ± SEM. E, normalized amount of LTP measured at 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after the first TB (shown as % ±SEM). Significant difference calculated by Student's t‐test, *** P ≤ 0.001. No significant differences were observed between WT and Fmr1−/y (KO) when LTP was induced by applying 20 TBs (P > 0.05). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Examples of raw traces in figures are scaled to the following: x‐axis, 5 ms; and y‐axis, 0.5 mV.

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) or MS‐Excel. Significant differences between groups were tested using Student's t‐test, one‐way ANOVA test or Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K‐S) test when appropriate.

Chemicals

The recordings were done in the presence or absence of different NMDAR antagonists: APV (50 μm), (1S,2S)‐1‐(4‐hydroxy‐phenyl)‐2‐(4‐hydroxy‐4‐phenylpiperidino)‐1‐propanol (CP‐101,606; 1 μm), [[[(1S)‐1‐(4‐bBromophenyl)ethyl]amino](1,2,3,4‐tetrahydro‐2,3‐dioxo‐5‐quinoxalinyl)methyl] phosphonic acid tetrasodium hydrate (NVP‐AAM077; 0.1 μm), 3‐chloro‐4‐fluoro‐N‐[4‐[[2‐(phenylcarbonyl)hydrazino]carbonyl]benzyl]benzenesulfonamide (TCN‐201; 10 μm)) and 2‐methyl‐6‐(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MPEP; 10 μm). All chemicals used were acquired from either Tocris (Ellisville, MO, USA) or Sigma‐Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Biochemistry

Synaptosome purification

Mouse hippocampus was rapidly dissected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80°C until use. Protein samples from P30–40 WT, Fmr1−/y and Grin2a−/−/Fmr1−/y (males only) mice were purified using the following steps: samples were dissected and homogenized on ice in a solution containing 0.32 m sucrose, 20 mm Hepes (pH7.4), 1 mm EDTA, 1× protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, 5 mm NaF and 1 mm sodium vanadarte. Samples were centrifuged at 135 g for 10 min at 4°C and the precipitate was discarded. The supernatant was centrifugated again at 13,500 g (4°C; 10 min). The pellet, which contains the crude synaptosomal fraction, was resuspended and sonicated in protein lysis buffer [50 mm Tris‐HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X‐100, 0.1% SDS, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 5 mm NaF, 1× protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail). Protein concentration was determined using a Pierce BCA protein assay.

Protein samples were boiled for 5 min in sample buffer before loading of 30 μg protein onto a 10% Tris‐HCl gels (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and electrophoresed at 100 V for about 90 min, resolved by SDS‐PAGE, and semi‐dry transferred (Bio‐Rad) to PVDF membranes for 45–60 min at 25 V. Blots were blocked in 1× casein buffer (Sigma, B6429) for 1–2 hours and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C followed by secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. For imaging, the GeneSys Pxi4 system was used following manufacturers’ protocols and bands were quantitated and normalized relative to the expression of β‐actin using Image‐J software (NIH). The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti‐GluN2B (1:1000, Abcam Cat# ab65783, RRID:AB_1658870); rabbit anti‐GluN2A (1:1000, Abcam Cat# ab133265, RRID:AB_11158532); rabbit anti‐beta actin (1:2000, Abcam Cat# ab8227, RRID:AB_2305186); chicken anti‐rabbit IgG (HRP)(1:2000, Abcam Cat# ab6829, RRID:AB_955444).

Results

Hippocampal long‐term potentiation

The Schaffer collateral–CA1 pyramidal cell synapse is one of the best‐studied synapses in the mammalian brain and exhibits mGluR‐dependent LTD (Bolshakov, 1994; Oliet et al. 1997), and NMDAR‐dependent LTP (Malenka & Nicoll, 1999; Lu & Malenka, 2012). Here, after collecting stable baseline responses in WT hippocampal slices, application of a train of 10 theta bursts (10 TBs) induced LTP (Fig. 1 Aa). Thus, 60‐min after application of 10 TBs, a clear and significant increase in the fEPSP slope in slices from WT mice was observed (139 ± 5%, P = 0.0001, n = 19). In contrast, in the Fragile X mouse (Fmr1−/y), using the same protocol did not elicit LTP; instead, the post‐tetanic potentiation decayed rapidly to baseline (108 ± 4%, P > 0.05, n = 12). The lack of LTP in the Fmr1−/y mice could be reversed by increasing the number of theta bursts to 20 (20 TBs, Fig. 1 Ab, KO: 135 ± 6%, P = 0.0001, n = 16). Next, to further investigate the threshold needed to induce LTP in Fmr1−/y mice, a stepwise increase in the number of theta bursts was applied to slices with a 30 min time interval. The first application of five TBs at time point 0 induced stable LTP in WT (147 ± 5%) but not in Fmr1−/y (117 ± 2%) mice, supporting impaired Fmr1−/y LTP. After 30 min another five TBs were applied. Again, in WT we observed a small but significant increase in LTP (180 ± 8%) but not in Fmr1−/y (126 ± 5%). After 60 min, application of an additional 10 TBs enhanced LTP in the WT to its maximal level (200 ± 10%) but had no effect on the Fmr1−/y (126 ± 9%). Finally, at 90 min, application of 20 TBs had no additional impact on WT LTP (191 ± 9%). However, in the Fmr1−/y mice, we observed full LTP that was not significantly different from WT (195 ± 17%, P > 0.05) (Fig. 1 D, E). One concern in this series of experiments could be that the lack of LTP in Fmr1−/y might be due to exhausted slices after repeated applications of TB protocols; however, as shown in Fig. 1 Ab, in our hands, only a single 20 TBs and not 10 TBs were able to induce stable LTP in naïve Fmr1−/y slices (Fig. 1 Aa,b). Overall these experiments confirm previous reports using different stimulation paradigms that the machinery for generating LTP in the Fmr1−/y mouse is present but not working properly (Godfraind et al. 1996; Li et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2011). Previously we have found that subtype‐specific NMDAR antagonists affect mGluR‐dependent LTD differently in the adult Fmr1−/y vs. WT mouse (Toft et al. 2016). Notably, we found that altered GluN2A/GluN2B balance sets the level of LTD in the adult Fmr1−/y mouse. The two main types of NMDARs in the brain are GluN2A‐ and GluN2B‐containing channels (Wyllie et al. 2013) and thus, we tested whether the GluN2A‐ and GluN2B‐specific inhibitors, TCN‐201 and CP‐101,606, respectively, affect LTP in the Fmr1−/y and WT hippocampal slices. Pre‐incubation slices with CP‐101,606 blocked LTP in WT after application of 10 TBs whereas in Fmr1−/y slices it had no apparent effects (Fig. 2 Aa,b).

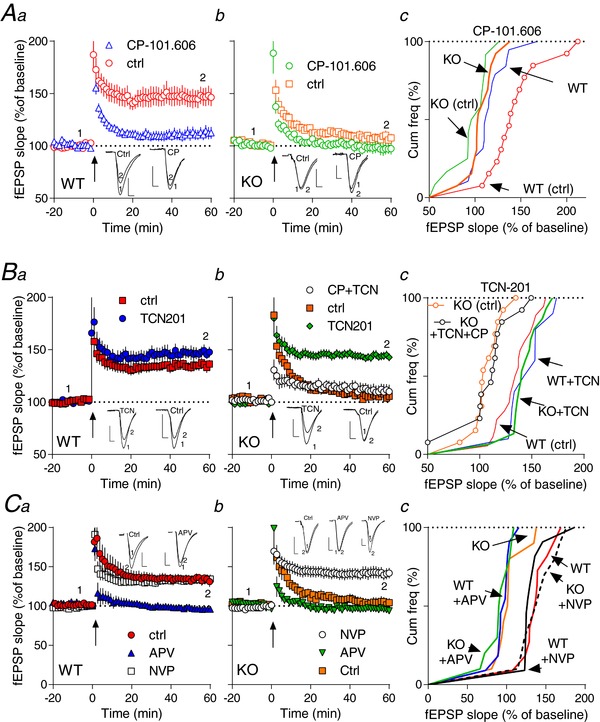

Figure 2. Differential effects of specific NMDAR subunit GluN2A and GluN2B inhibition on LTP in Fmr1−/y and WT.

Aa‐b, Ba‐b, time course of synaptic responses shown as mean fEPSP slope as a percentage of baseline. Bars represent ± SEM. LTP induction by TBs is indicated by an arrow at time 0 with 10 theta bursts. Ten minutes before induction of LTP, the NMDAR subunit GluN2B (Aa‐b) or GluN2A (Ba‐b) antagonist was applied and was left during the remaining of the experiment. In Bb, superimposed is co‐application of CP101.606+TCN201 (CP+TCN) on Fmr1−/y (KO). Ac, Bc, cumulative plots of normalized slope from Aa‐b and Ba‐b. There was a statistical difference among the groups [in A: WT(ctrl) vs. WT(CP), KO(CP) and KO(ctrl); in B: KO and KO(TCN+CP) vs. WT, WT(TCN) and KO(TCN)] determined by one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post‐hoc test; (Ac): F 3,53 = 10.64, P < 0.0001; (Bc): F 4,64 = 14.74, P < 0.0001. Ca‐b, time course of synaptic responses shown as mean fEPSP slope as a percentage of baseline in WT (a) or Fmr1−/y (KO) (b). Induction of LTP is indicated by an arrow (Ca‐b). Application of 100 nm NVP‐AAM077 (NVP) had no apparent effects on LTP in WT (a) but completely rescued LTP in Fmr1−/y (KO) (b). Application of APV completely inhibited LTP 60 min after induction in both WT and Fmr1−/y (KO) (Ca‐b). Cc, cumulative plots of normalized slope from Ca‐b. There was a statistical difference among the groups [KO(ctrl), WT(APV), KO(APV) vs. WT(ctrl), KO(NPV) and WT(NPV)] determined by one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post‐hoc test; F 5,57 = 18.83, P < 0.001. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In contrast, pre‐incubation with the selective GluN2A antagonist TCN‐201 (Hansen et al. 2012) had no effects on LTP in WT but, surprisingly, completely rescued LTP in Fmr1−/y slices (143 ± 4%, P = 0.0001, n = 15; Fig. 2 Ba,b). As a control, we next tested another relative selective GluN2A inhibitor, NVP‐AAM077 [but which is less selective than TCN‐201: ∼6–12× selectivity for GluN2A over GluN2B (Yashiro & Philpot, 2008)] in our slice preparations. Pre‐incubation of Fmr1−/y slices with NVP‐AAM077 produced similar effects as observed with TCN‐201 (Fmr1−/y NVP: 134 ± 6%, n = 11 vs. Fmr1−/y TCN201: 143 ± 4%, n = 15, P > 0.05)(Fig. 2 Bb, Cb), strongly supporting a dysregulatory role of GluN2A in the Fmr1−/y mouse brain. Furthermore, in other control experiments, application of the broad‐spectrum NMDAR antagonist, APV, blocked LTP in both WT and Fmr1−/y slices (Fig. 2 C), confirming the NMDAR dependency of this type of LTP (Morris et al. 1986).

Long‐term depression

If blockage of GluN2A‐containing NMDARs leads to rescue of LTP in Fmr1−/y, then what about LTD? In agreement with Toft et al. (2016) and Huber et al. (2002), using a standard 1 Hz double‐stimulation protocol (PP‐LFS) in the presence of the NMDAR antagonist, APV, to induce mGluR5‐dependent LTD, significantly increased LTD in the Fmr1−/y mice [KOAPV: 40.4 ± 4.2% (n = 15) over WT (WTAPV: 24.1 ± 3.6% (n = 15); P < 0.01 Student's t‐test; Fig. 3 A,B,D)].

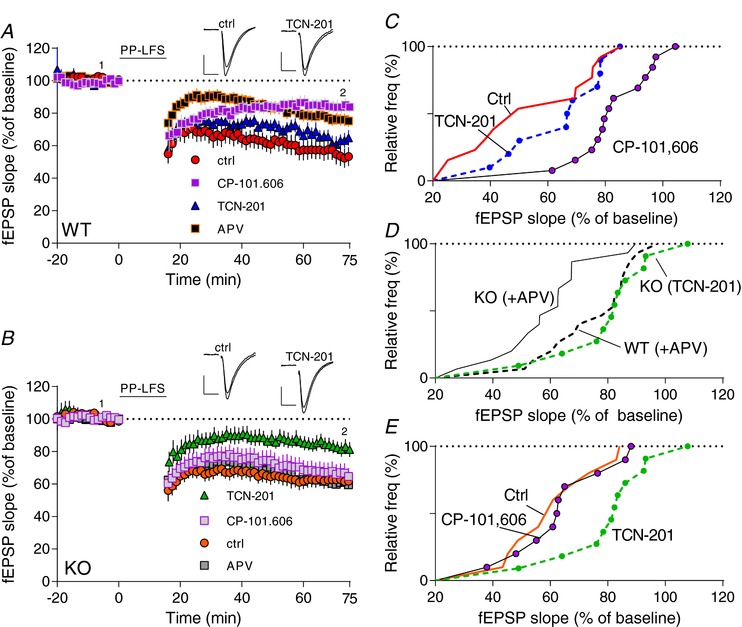

Figure 3. Hyperarctive mGluR5‐dependent LTD signalling in KO strongly depends upon GluN2A.

A, B, time course of synaptic response shown as mean fEPSP slope as a percentage of baseline. mGluR5‐dependent LTD (in the absence of APV) was induced by 900 double‐pulses (PP‐LFS) at 1 Hz (black bar at top) (red trace in A and orange trace in B). Application of TCN‐201 before LTD induction reduced LTD in KO (B) but not in WT (A). Application of CP‐101,606 or APV reduced LTD in WT but not in KO. C–E, cumulative plots of normalized slope from A and B. D, cumulative plots of mGluR‐dependent LTD data for WT and KO recorded in the presence of APV, P < 0.009 (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) (data from A and B). Superimposed is KO‐LTD in the presence of TCN‐201 but not APV (green trace). There was a statistical difference among the groups in C (F 2,33 = 9.590, P < 0.0005 and E (F 2,28 = 5.000, P < 0.01) determined by one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post‐hoc test. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Recording in the absence of any NMDAR antagonists revealed the ‘total’ LTD component in this process (LTDctrl). Thus, in control experiments (in the absence of any NMDAR antagonist), LTD in WT was significant increased (WTctrl: 46 ± 6%) over recordings in the presence of APV (P < 0.005). Subtracting mGluR‐LTDAPV from LTDCtrl reveals the NMDAR‐sensitive component (LTDNMDAR); in WT, this component comprised ∼22%. In contrast, in Fmr1−/y, control LTD (Fmr1−/y ctrl : 38 ± 5%) was not significantly different from recordings in the presence of APV (Fmr1−/y APV: 40 ± 4; P > 0.05), indicating a non‐existent NMDAR component (∼0%). Next, pre‐incubation slices with CP‐101,606 reduced LTD in WT (WTCP: 16 ± 3%) to roughly the same level as observed with APV present (WTAPV: 24 ± 4%; P > 0.05), suggesting that the WT‐NMDAR component (∼22%) is primarily dependent on GluN2B. In contrast, not surprisingly, incubation of Fmr1−/y slices with CP‐101.606 had no apparent effect on LTD (Fmr1−/y CP: 36 ± 5% vs. Fmr1−/y ctrl: 38 ± 5; P > 0.5).

Furthermore, incubation with TCN‐201 had no significant effect on WT‐LTD (WTTCN: 34 ± 5% vs. WTAPV: 24 ± 4%, P > 0.05), again supporting the suggestion that the NMDAR component in WT is mainly GluN2B‐dependent.

Interestingly, repeating this experiment with the GluN2A antagonist, TCN‐201, revealed that Fmr1−/y recapitulated the WT when GluN2A was blocked (Fmr1−/y TCN: 19 ± 5% vs. WTAPV: 24 ± 4%; P > 0.05, Fig. 3 D). These experiments suggest that in Fmr1−/y slices, GluN2A‐containing NMDARs apparently not only play prominent roles in LTP but also in mGluR‐dependent LTD. This supports our hypothesis that blockage using GluN2A‐specific antagonists shifts the LTP–LTD threshold balance towards more LTP and less LTD at the CA3→CA1 synapse in Fmr1−/y mice.

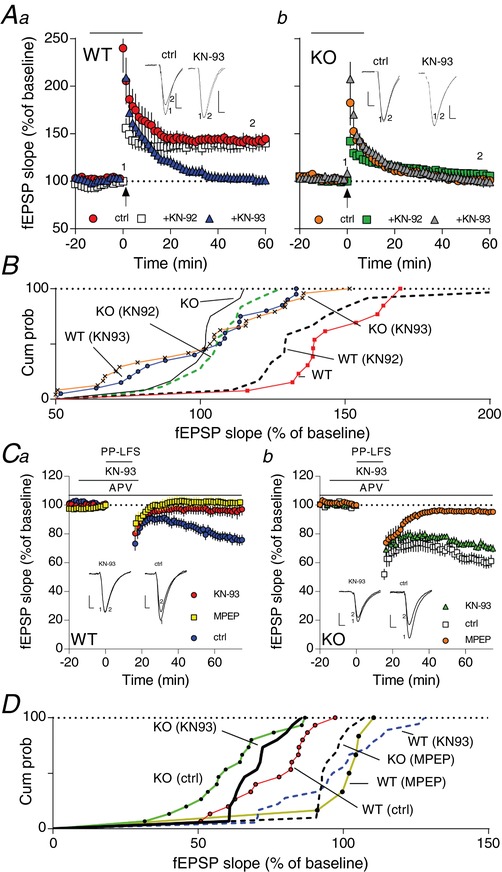

Activation of NMDARs leads to an influx of intracellular calcium that precedes activation of multiple kinases, including Ca2+/calmodulin‐kinase II (CaMKII), which are important steps involved in the induction of synaptic plasticity. In a set of control experiments, we next tested whether blocking CaMKII had any impact upon establishing LTP and LTD. Blocking CaMKII activity using the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 blocked WT‐LTP but had no apparent effects on Fmr1−/y‐LTP. In addition, the KN93 inactive analogue KN92 appeared to have no effects in both WT and Fmr1−/y mice (Fig. 4 A). Interestingly, blocking CaMKII in PP‐LFS with KN93 inhibited LTD in the WT but not in Fmr1−/y mice (Fig. 4 C). Combined, these experiments support an important role for GluN2B in establishing LTP and LTD in WT but not in Fmr1−/y mice.

Figure 4. Inhibition of CaMKII prevents LTP and LTD in WT but not Fmr1−/y .

Aa‐b, time course of synaptic responses shown as mean fEPSP slope as a percentage of baseline. Bars represents ± SEM. LTP induction by TBs is indicated by the arrow at time 0 with 10 theta bursts. Fifteen minutes before induction of LTP, the CaMKII antagonist, KN‐93 (10 μm) or the inactive analogue, KN‐92 (10 μm), were applied and washed off again 5 min after LTP induction on WT (a) or KO (b) slices (shown as black bar at the top). B, cumulative plots of normalized slope from Aa‐b. There was a statistical difference among the groups [WT, WT(KN‐92) vs. the remaining four conditions determined by one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post‐hoc test; F 5,93 = 12.89, P < 0.0001). Ca‐b, time course of synaptic response shown as mean fEPSP slope as a percentage of baseline. mGluR5‐dependent LTD (in the presence of APV) was induced by 900 double‐pulses (PP‐LFS) at 1 Hz (black bar at top) (red trace in Ca and orange trace in Cb). Application of KN‐93 15 min before LTD induction reduced LTD in WT (Ca) but not in KO (Cb). KN‐93 was washed off 5 min after LTD induction. Superimposed on the figure are data showing that application of MPEP blocked LTD in both WT and KO, confirming the mGluR5 dependency. Note that ctrl for this panel means including APV. D, cumulative plots of normalized slope from Ca‐b. There was a statistical difference among the groups in Ca (F 2,36 = = 10.05; P < 0.0003) and in Cb (F 2,37 = 31.01, P < 0.0001) determined by one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post‐hoc test. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Genetic elimination of GluN2A in Fmr1−/y

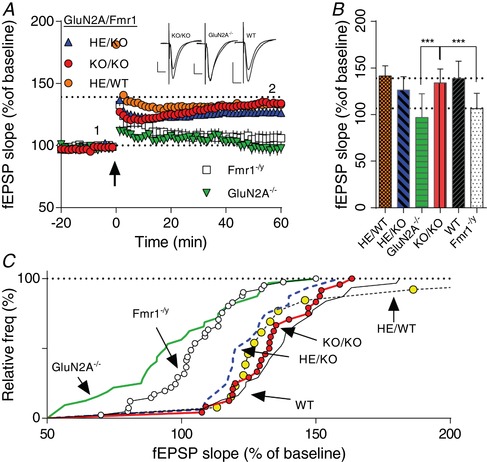

A possible explanation of our findings with TCN‐201 could be an unknown compound side effect(s) in the Fmr1−/y mouse. To address this concern we generated offspring from Fmr1−/y ×Grin2a−/− matings and obtained the following genotypes: Grin2a−/−, Grin2a+/−, Fmr1−/y, Fmr1−/y/Grin2a−/−, Fmr1−/y/Grin2a+/− and WT animals. Challenging hippocampal slices from the six genotypes with the 10 TBs protocol confirmed normal LTP in WT and no or very little LTP in the Fmr1−/y offspring (Fig. 5). Furthermore, similar to Sakimura et al. (1995), we found impaired LTP in Grin2a−/− littermates. Interestingly, in slices of the double knock‐out, Fmr1−/y/Grin2a−/−, at 60 min after LTP induction, LTP was normalized to the same degree as observed in WT littermates [134 ± 3% (n = 24) vs. 139 ± 3% (n = 31) in WT; P > 0.05, unpaired Student's t‐test; Fig. 5].

Figure 5. Normal hippocampal LTP in a double mutant Grin2a(−/−)/Fmr1−/ y mouse.

Grin2a(−/−) mice were crossed with Fmr1−/y to create a double mutant GluN2A( −/− )/Fmr1−/y (KO/KO) mouse. A, time course of synaptic responses shown as mean fEPSP slope as a percentage of baseline. Bars represent ± SEM. LTP induction by TBs as indicated by an arrow at time 0 with 10 theta bursts. Crossing Fmr1−/y with Grin2a−/− generated six different genotypes: Grin2a−/− (GluN2AKO); Grin2a−/−/Fmr1−/y (KO/KO); Fmr1−/y (Fmr1KO); Grin2a+/− (HE/WT); Grin2a+/−/Fmr1−/y (HE/KO); and WT. LTP from WT at 60 min is shown with a dotted line (at 139%). Inset shows representative traces from indicated time points. B, average amount of LTP at 60 min after TB induction. There was a significant difference between GluN2A( −/− )/Fmr1−/y (KO/KO) and GluN2A−/− and between GluN2A( −/− )/Fmr1−/y (KO/KO) and Fmr1−/y (F 5,151 = 20.84, P < 0.0001, one‐way ANOVA followed by a Tukey test). C, cumulative probability of fEPSP 60 min after LTP induction in individual slices. There was a significant difference between GluN2A( −/− )/Fmr1−/y (KO/KO) and GluN2A −/− and between GluN2A( −/− )/Fmr1−/y (KO/KO) and Fmr1−/y (P < 0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

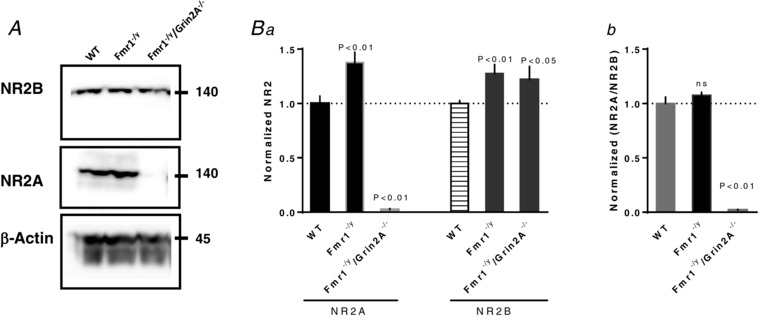

In a final control experiment, we measured the synaptosomal protein levels in WT and Fmr1−/y hippocampus. As reported for adult animals (P60–80; Toft et al. 2016), here we also found that both GluN2A and GluN2B protein levels were elevated in Fmr1−/y mice (Fig. 6). The ratio GluN2A/GluN2B was increased slightly in the Fmr1−/y mice but at this developmental stage (P30–40) was not quite significant (108 ± 3%; P > 0.05). Not surprisingly, the GluN2A/Glun2B ratio in Grin2A−/−/Fmr1−/y mutants was strongly reduced (2 ± 1%; P < 0.01; Fig. 6 Bb). Interestingly, in the Grin2A−/−/Fmr1−/y mutants, GluN2B was slightly upregulated when compared to WT (122 ± 11%; P < 0.05, Fig. 6 Ba). Combined, these experiments support a strong role for dysregulated NMDARs in the pathophysiology of FXS.

Figure 6. Enhanced hippocampal GluN2A and GluN2B NMDAR protein levels in Fmr1−/y mice.

A, representative immunoblots of GluN2A and GluN2B from synaptosome lysate. Hippocampus proteins were purified from 4–5 WT or Fmr1−/y mice and normalized to the β‐actin level. Ba, both GluN2A and GluN2B were significantly elevated in Fmr1−/y compared to WT mice. There was a significant difference between the groups (GluN2A: n = 7; F 2,23 = 40.18; P < 0.01; GluN2B: F 2,20 = 5.65;P < 0.01; n = 7; one‐way ANOVA followed by a Tukey test). Bb, the GluN2A/GluN2B ratio is not significantly different between Fmr1−/y and WT mive at this age. There was a significant difference between WT and Grin2A−/−/Fmr1−/y as indicated on the figure (F 2,23 = 86.11; one‐way ANOVA followed by a Tukey test).

Discussion

NMDARs are involved in many different forms of synaptic plasticity. LTP and LTD are measurements of synaptic plasticity, which was to be important for information storage in the brain and cognitive processes (Malenka & Nicoll, 1999). Here we find that TBs induced an NMDAR‐dependent form of LTP that is impaired in Fmr1−/y mice. Interestingly, the impaired LTP can be fully rescued by pharmacological blockade or genetic inactivation of GluN2A‐containing NMDARs.

Several reports have described LTP deficit in multiple brain regions in Fmr1−/y mice (Godfraind et al. 1996; Paradee et al. 1999; Li et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2005; Desai et al. 2006; Meredith et al. 2007; Shang et al. 2009) and in agreement with both Lauterborn et al. (2007) and Lee et al. (2011), we observed a clear and strong impairment in hippocampal CA3‐to‐CA1 LTP. The impairment depends strongly upon stimulation intensity: fewer TBs were needed to induce LTP in hippocampal slices of WT than Fmr1−/y mice (Sidorov et al. 2013). This is in accordance with a higher threshold to induce hippocampal LTP in Fmr1−/y mice. Under our experimental conditions only very ‘harsh’ TBs (20 TBs) could induce normal LTP in the Fmr1−/y mice. It is interesting to note that induction of LTP in KO slices did not alter the short‐term facilitation of the synaptic response immediately after tetanic stimulation (post‐tetanic potentiation), but this increase was short‐lived because the amplitude of the postsynaptic response returned to baseline levels within 10–15 min. This suggests that the influence of the Fmr1 mutation lies outside the LTP mechanism, but within a mechanism that influences the ability to reach LTP threshold. Such mechanism could be changed dendritic membrane properties, such as altered ion channel expression patterns that affect neuronal excitability (Contractor et al. 2015).

Role of NMDARs in LTP

The main types of hippocampal NMDARs contain, in addition to the obligatory GluN1 subunit, the subunit GluN2A or GluN2B, and although still debated based upon mainly pharmacological experiments (Bartlett et al. 2007; Morishita et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2009), both subunit types have been suggested to play distinct roles in long‐term synaptic plasticity (Liu et al. 2004; Massey et al. 2004). In agreement with this, we found both GluN2A and GluN2B proteins were present and upregulated in the Fmr1−/y hippocampus at this developmental stage. FMRP is a negative regulator of translation of many proteins including GluN2A and GluN2B. Thus, both GluN2A and GluN2B have been reported to be upregulated in Fmr1−/y mice (Schütt et al. 2009; Edbauer et al. 2010; Darnell et al. 2011; Toft et al. 2016). Interestingly, GluN2B was being compensated for a lack of GluN2A in Grin2A−/−/Fmr1−/y. However, no difference for GluN2B between Grin2A−/−/Fmr1−/y and Fmr1−/y was found, suggesting this upregulation is driven by a lack of FMRP rather than lack of GluN2A.

A third class of NMDARs exists containing both types of GluN2: triheteromeric NMDARs (GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2B) (Rauner & Köhr, 2011; Tovar et al. 2013). However, knowledge of the role(s) of triheteromeric receptors in plasticity and how they are pharmacologically regulated is limited. Despite such potential limitations, our characterization of WT and Fmr1−/y CA1 synapses has revealed several important findings: in contrast to the CA1 synapses in Fmr1−/y mice where the main NMDARs involved in TB‐LTP are GluN2A‐containing NMDARs, WT mice depend more strongly upon GluN2B‐containing receptors. Thus, in WT, TCN‐201 had no apparent effects whereas in Fmr1−/y mice the impaired LTP was restored. This effect was not only observed using TCN‐201; testing with another GluN2A‐specific compound, NVP‐AAM077 (Berberich et al. 2005), had similar effects on LTP in Fmr1−/y. Rescuing Fmr1−/y‐LTP depends exclusively upon blocking GluN2A, suggesting that GluN2A‐containing NMDARs are, at least in part, functioning as heterodimeric GluN1/2A NMDARs in the Fmr1−/y mice (in contrast to triheteromeric GluN1/2A/2B). Furthermore, such a heterodimeric GluN2A‐containing NMDAR (GluN1/2A) pool either does not exist in the WT synapse or it exists but at different locations. Furthermore, just as with the importance of GluN2B‐containing NMDARs in WT LTP, these experiments also reveal that the residual NMDAR activity – the GluN2B‐containing NMDARs – in the Fmr1−/y mice is still crucial for LTP induction. Hence, in the Fmr1−/y mutants, blockage of both GluN2A and GluN2B did not rescue LTP (Fig. 2 Cb), which was also noted with the application of the broad‐spectrum NMDAR inhibitor, APV (Fig. 3). In other words, functional GluN2B‐containing NMDARs in LTP is also a necessity in Fmr1−/y mice.

To validate GluN2A as a potential therapeutic Fmr1 target, we crossed Fmr1−/y mice with the Grin2a−/− mouse to create a double knockout mouse (GluN2a−/−/Fmr1−/y mice). In contrast to pharmacological blocking GluN2A in WT, we found, in agreement with others (Kiyama et al. 1998; Köhr et al. 2003; Berberich et al. 2007), that mice that lack the GluN2A subunit, or just the GluN2A carboxy‐terminal tail (Sprengel et al. 1998; Köhr et al. 2003), exhibit deficits in LTP. This difference may be the product of acute vs. chronic blockage/removal of the receptor in WT. In Fmr1−/y mice, however, both acute and chronic treatment of GluN2A rescued the phenotype. The exact reasons for this difference are not clear however, and this puts GluN2A in a pivotal position; too much or too little GluN2A signalling downregulates synaptic plasticity. In summary, pharmacological blockage or genetic deletion of GluN2A ameliorates the synaptic plasticity deficit in Fmr1−/y mice, supporting an important role for GluN2A in hippocampal LTP in FXS.

Role of NMDARs in LTD

The level of neuronal synaptic plasticity is set by a delicate balance between LTP and the opposite process, LTD. It is well known that the Fmr1−/y mouse exhibits an enhanced mGluR‐dependent form of LTD in CA1 (Huber et al. 2002; Toft et al. 2016) that depends upon active NMDARs (Toft et al. 2016). Interestingly, in contrast to adult mice, here we found that the levels of LTD at this younger (juvenile) developmental stage in the Fmr1−/y mice depends primarily upon the activity of GluN2A‐containing receptors. Thus, inhibiting GluN2A‐containing NMDARs not only rescued the impaired LTP but also reduced the enhanced mGluR‐LTD observed in the Fmr1−/y mouse (Fig. 3). This was in contrast to WT, where we found that inhibiting GluN2B‐containing NMDARs blocked LTD, supporting the findings from Liu et al. (2004) and consistent with our original conclusion (see e.g. fig. 5 in Toft et al. 2016) that NMDARs are indeed strongly dysregulated in the FmR1−/y mouse. Thus, we recently described that the GluN2A/GluN2B ratio in the Fmr1−/y mouse appears to be out of balance (Toft et al. 2016) and reported that this strongly affected Fmr1−/y mGluR‐LTD. An interesting twist presented here is that blocking all NMDAR signalling (by APV) in Fmr1−/y mice revealed a non‐existent LTD NMDAR component. However, at the same time, inhibiting exclusively GluN2A‐containing NMDARs (by TCN‐201) rescued the well‐characterized and well‐known enhanced mGluR‐LTD in FXS, suggesting that Fmr1−/y‐LTD is still NMDAR‐regulated. The findings presented here support our previous findings (Toft et al. 2016) that NMDAR‐signalling and mGluR‐dependent LTD are intertwined and not easy to dissect (at least not in FXS). Thus, NMDARs are indeed known for stimulating mGluRs, and vice versa (Aniksztejn et al. 1992; Harvey & Collingridge, 1993; Challiss et al. 1994; Lüthi et al. 1994; Fitzjohn et al. 1996; Gereau & Heinemann, 1998; Alagarsamy et al. 1999; Collett & Collingridge, 2004).

Activation of NMDAR gives rise to calcium influx, which in turn leads to multiple events, including CaMKII activation. CaMKII is heavily implicated in synaptic plasticity, especially LTP (Lisman et al. 2012) but also LTD (Coultrap et al. 2014). Interestingly, CaMKII is one of many kinases, scaffolding and other synaptic proteins that are upregulated and/or dysregulated in Fmr1−/y animals (Zalfa et al. 2003, 2006; Bassell & Warren, 2008; Schütt et al. 2009; Osterweil et al. 2010; Edbauer et al. 2010; Darnell & Klann, 2013). In this study, we show that after blockage of CaMKII, both LTP and LTD in WT were strongly affected (Fig. 4). A current model suggests that once activated, CaMKII translocates from the cytoplasm to the synapse where it will bind to NMDARs, most strongly to GluN2B‐containing NMDARs, supporting an important role for GluN2B in WT. Based upon our data, we would predict that CaMKII in the Fmr1−/y mouse would play only a minor role. Indeed, blocking had no apparent effects in synaptic plasticity in Fmr1−/y mice, supporting the hypothesis that Fmr1−/y is not dependent upon GluN2B dependency.

In contrast, our data support an important role for GluN2A in Fmr1−/y mutants and demonstrate that activity of GluN2A can up‐ or downscale synaptic strength by changing the thresholds of LTP and LTD. This suggests that once the dysregulated GluN2A‐containing receptors are under pharmacological (and/or genetic control) Fmr1−/y recapitulates both WT LTP and WT LTD.

Therapeutic target in FXS

NMDARs have strong potential as therapeutic targets in multiple brain disorders, including FXS (Paoletti et al. 2013; Gurney et al. 2017). However, all NMDAR targets are heavily involved in normal cognitive memory, neuronal plasticity and neuronal toxicity. Thus, lowering NMDAR activity can result in serious pathological conditions. Until recently, most of the NMDAR compounds that showed most promise as inhibitors of pathological conditions also blocked normal neuronal function and consequently had severe and unacceptable side effects. As presented here, this puts new GluN2A‐subtype specific NMDAR inhibitors (e.g. TCN‐210) in a unique light (Bettini et al. 2010; see also Yuan et al. 2015). Our data support GluN2A‐specific compounds as interesting potential lead compounds for future FXS research. Thus, we show here that blockage of excess glutamate activity in FXS can rescue hippocampal LTP possibly through inhibition of specific heterodimeric GluN2A NMDARs. Importantly, this suggests that the remaining NMDAR activity after GluN2A blockage has the potential to restore hyperactive brain function to (a more) normal‐like level in FXS patients. However, in GluN2A‐deficient mice, short‐term memory deficiencies were observed (Bannerman et al. 2008), and GluN2A deficiencies and dysfunction are tightly associated with neurodevelopmental disorders in human patients (Burnashev & Szepetowski, 2015). Thus, it remains to be determined whether GluN2A‐dependent cognitive and behavioural deficiencies still show effects in the genetic background of mice with FXS phenotypes.

Additional information

Funding

This work was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation, the Riisfort Foundation and the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF – 4004‐00188).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

TGB and CJL designed the experiments and wrote the paper; TGB, CJL and AKHT conducted the experiments. All authors read and approved submission of this version of the paper.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Drs Mark Bear and Aurore Thomazeau (MIT, USA), and to Dr Rolf Sprengel (Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, Germany) for critical reading and comment on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Biography

Camilla Johanne Lundbye holds an MSc in Molecular Biology from Aarhus University where she gained a broad knowledge in biological processes, co‐authored three articles and through optional parts of her study chose to focus on neuroscience. Her master's thesis was based upon electrophysiological experiments on a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome. Camilla is currently doing her PhD at University of Toronto in Dr Graham Collingridge's lab, where she is researching learning and memory in mouse models of different autism risk genes. With this research, the goal is to identify common pathways in which these genes are involved, with a particular focus on synaptic plasticity.

Present address: Department of Physiology, University of Toronto, Faculty of Medicine, Toronto, ON, M5S 1A8, Canada.

References

- Alagarsamy S, Marino MJ, Rouse ST, Gereau RW, Heinemann SF & Conn PJ (1999). Activation of NMDA receptors reverses desensitization of mGluR5 in native and recombinant systems. Nat Neurosci 2, 234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aniksztejn L, Otani S & Ben‐Ari Y (1992). Quisqualate metabotropic receptors modulate NMDA currents and facilitate induction of long‐term potentiation through protein kinase C. Eur J Neurosci 4, 500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Niewoehner B, Lyon L, Romberg C, Schmitt WB, Taylor A, Sanderson DJ, Cottam J, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Kohr G, Rawlins JNP, Köhr G & Rawlins JNP (2008). NMDA receptor subunit NR2A is required for rapidly acquired spatial working memory but not incremental spatial reference memory. J Neurosci 28, 3623–3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes SA, Wijetunge LS, Jackson AD, Katsanevaki D, Osterweil EK, Komiyama NH, Grant SGN, Bear MF, Nagerl U V., Kind PC & Wyllie DJA (2015). Convergence of hippocampal pathophysiology in Syngap+/− and Fmr1−/y mice. J Neurosci 35, 15073–15081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett TE, Bannister NJ, Collett VJ, Dargan SL, Massey P V., Bortolotto ZA, Fitzjohn SM, Bashir ZI, Collingridge GL & Lodge D (2007). Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B‐containing NMDA receptors in LTP and LTD in the CA1 region of two‐week old rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 52, 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ & Warren ST (2008). Fragile X Syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron 60, 201–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberich S, Jensen V, Hvalby Ø, Seeburg PH & Kohr G (2007). The role of NMDAR subtypes and charge transfer during hippocampal LTP induction. Neuropharmacology 52, 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberich S, Punnakkal P, Jensen V, Pawlak V, Seeburg P, Hvalby Ø & Kohr G (2005). Lack of NMDA receptor subtype selectivity for hippocampal long‐term potentiation. J Neurosci 25, 6907–6910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettini E, Sava A, Griffante C, Carignani C, Buson A, Capelli AM, Negri M, Andreetta F, Senar‐Sancho SA, Guiral L & Cardullo F (2010). Identification and characterization of novel NMDA receptor. JPET 335, 636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boda B, Mendez P, Boury‐Jamot B, Magara F & Muller D (2014). Reversal of activity‐mediated spine dynamics and learning impairment in a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome. Eur J Neurosci 39, 1130–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolshakov VY SS (1994). Postsynaptic induction and presynaptic expression of hippocampal long‐term depression. Science 264, 1148–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom C, Yu YS, Majaess N, Vetrici M, Gil‐Mohapel J & Christie BR (2016). Hippocampal dysfunction and cognitive impairment in Fragile‐X Syndrome. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 68, 563–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N & Szepetowski P (2015). NMDA receptor subunit mutations in neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol 20, 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challiss RA, Mistry R, Gray DW & Nahorski SR (1994). Modulatory effects of NMDA on phosphoinositide responses evoked by the metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist 1S,3R‐ACPD in neonatal rat cerebral cortex. Br J Pharmacol 112, 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Kurup PK, Lundbye CJ, Hugger Toft AK, Kwon J, Benedict J, Kamceva M, Banke TG & Lombroso PJ (2018). STEP inhibition reverses behavioral, electrophysiologic, and synaptic abnormalities in Fmr1 KO mice. Neuropharmacology 128, 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L & Toth M (2001). Fragile X mice develop sensory hyperreactivity to auditory stimuli. Neuroscience 103, 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffee B, Keith K, Albizua I, Malone T, Mowrey J, Sherman SL & Warren ST (2009). Incidence of Fragile X Syndrome by newborn screening for methylated FMR1 DNA. Am J Hum Genet 85, 503–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collett VJ & Collingridge GL (2004). Interactions between NMDA receptors and mGlu5 receptors expressed in HEK293 cells. Br J Pharmacol 142, 991–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Dutch‐Belgian Fragile X Consortium (1994). Fmr1 knockout mice: a model to study fragile X mental retardation. Cell 78, 23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor A, Klyachko VA & Portera‐Cailliau C (2015). Altered neuronal and circuit excitability in Fragile X Syndrome. Neuron 87, 699–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coultrap SJ, Freund RK, O'Leary H, Sanderson JL, Roche KW, Dell'Acqua ML & Bayer KU (2014). Autonomous CaMKII mediates both LTP and LTD using a mechanism for differential substrate site selection. Cell Rep 6, 431–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KYS, Mele A, Fraser CE, Stone EF, Chen C, Fak JJ, Chi SW, Licatalosi DD, Richter JD & Darnell RB (2011). FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell 146, 247–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC & Klann E (2013). The translation of translational control by FMRP: therapeutic targets for FXS. Nat Publ Gr 16, 1530–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Casimiro TM, Gruber SM, W P & Vanderklish PW (2006). Early postnatal plasticity in neocortex of Fmr1 knockout mice. J Neurophysiol 1734–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dölen G & Bear MF (2008). Role for metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) in the pathogenesis of fragile X syndrome. J Physiol 586, 1503–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edbauer D, Neilson JR, Foster KA, Wang C‐F, Seeburg DP, Batterton MN, Tada T, Dolan BM, Sharp PA & Sheng M (2010). Regulation of synaptic structure and function by FMRP‐associated microRNAs miR‐125b and miR‐132. Neuron 65, 373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisch GS, Simensen RJ & Schroer RJ (2002). Longitudinal changes in cognitive and adaptive behavior scores in children and adolescents with the Fragile X mutation or autism. J Autism Dev Disord 32, 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzjohn S, Irving A, Palmer M, Harvey J, Lodge D & Collingridge G (1996). Activation of group I mGluRs potentiates NMDA responses in rat hippocampal slices. Neurosci Lett 203, 211–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereau RW & Heinemann SF (1998). Role of protein kinase C phosphorylation in rapid desensitization of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5. Neuron 20, 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfraind J‐M, Reyniers E, De Boulle K, D'Hooge R, De Deyn PP, Bakker CE, Oostra BA, Kooy RF & Willems PJ (1996). Long‐term potentiation in the hippocampus of fragile X knockout mice. Am J Med Genet 64, 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy D (2015). Principles and standards for reporting animal experiments in The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology . J Physiol 593, 2547–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney ME, Cogram P, Deacon RM, Rex C & Tranfaglia M (2017). Multiple behavior phenotypes of the Fragile‐X Syndrome mouse model respond to chronic inhibition of phosphodiesterase‐4D (PDE4D). Sci Rep 7, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ (1996). Physical and behavioral phenotype, 3–87. In Fragile X Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research, ed. Hagerman R. & Cronister A. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KB, Ogden KK & Traynelis SF (2012). Subunit‐selective allosteric inhibition of glycine binding to NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 32, 6197–6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey J & Collingridge GL (1993). Signal transduction pathways involved in the acute potentiation of NMDA responses by 1S,3R‐ACPD in rat hippocampal slices. Br J Pharmacol 109, 1085–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Gallagher SM, Warren ST & Bear MF (2002). Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 7746–7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ & Leehey MA (2007). Fragile‐X syndrome and fragile X‐associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: two faces of FMR1. Lancet Neurol 6, 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyama Y, Manabe T, Sakimura K, Kawakami F, Mori H & Mishina M (1998). Increased thresholds for long‐term potentiation and contextual learning in mice lacking the NMDA‐type glutamate receptor ε1 subunit. J Neurosci 18, 6704–6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhr G, Jensen V, Koester HJ, Mihaljevic ALA, Utvik JK, Kvello A, Ottersen OP, Seeburg PH, Sprengel R & Hvalby Ø (2003). Intracellular domains of NMDA receptor subtypes are determinants for long‐term potentiation induction. J Neurosci 23, 10791–10799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterborn JC, Rex CS, Kramár E, Chen LY, Pandyarajan V, Lynch G & Gall CM (2007). Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor rescues synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci 27, 10685–10694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Ge W‐P, Huang W, He Y, Wang GX, Rowson‐Baldwin A, Smith SJ, Jan YN & Jan LY (2011). Bidirectional regulation of dendritic voltage‐gated potassium channels by the Fragile X mental retardation protein. Neuron 72, 630–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MH, Tanimura Y, Lee LW & Bodfish JW (2007). Animal models of restricted repetitive behavior in autism. Behav Brain Res 176, 66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Pelletier MR, Perez Velazquez J‐L & Carlen PL (2002). Reduced cortical synaptic plasticity and GluR1 expression associated with fragile X mental retardation protein deficiency. Mol Cell Neurosci 19, 138–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J, Yasuda R & Raghavachari S (2012). Mechanisms of CaMKII action in long‐term potentiation. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 169–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang YT, Sheng M, Auberson YP & Wang YT (2004). Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science 304, 1021–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C & Malenka RC (2012). NMDA receptor‐dependent long‐term potentiation and long‐term depression (LTP / LTD). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthi A, Gähwiler BH & Gerber U (1994). Potentiation of a metabotropic glutamatergic response following NMDA receptor activation in rat hippocampus. Pflugers Arch 427, 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC & Nicoll RA (1999). Long‐term potentiation–a decade of progress? Science 285, 1870–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey P V, Johnson BE, Moult PR, Auberson YP, Brown MW, Molnar E, Collingridge GL & Bashir ZI (2004). Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B‐containing NMDA receptors in cortical long‐term potentiation and long‐term depression. J Neurosci 24, 7821–7828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith RM, Holmgren CD, Weidum M, Burnashev N & Mansvelder HD (2007). Increased threshold for spike‐timing‐dependent plasticity is caused by unreliable calcium signaling in mice lacking Fragile X gene Fmr1. Neuron 54, 627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalon A, Sidorov M, Ballard TM, Ozmen L, Spooren W, Wettstein JG, Jaeschke G, Bear MF & Lindemann L (2012). Chronic pharmacological mGlu5 inhibition corrects fragile X in adult mice. Neuron 74, 49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita W, Lu W, Smith GB, Nicoll RA, Bear MF & Malenka RC (2007). Activation of NR2B‐containing NMDA receptors is not required for NMDA receptor‐dependent long‐term depression. Neuropharmacology 52, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RGM, E A, Lynch G & M B (1986). Selective impairment of learning and blockage of long‐term potentiation by an N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate receptor antagonist, AP5. Nature 320, 264–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves G, Cooke SF & Bliss TVP (2008). Synaptic plasticity, memory and the hippocampus: a neural network approach to causality. Nat Rev Neurosci 9, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimchinsky EA, Oberlander AM & Svoboda K (2001). Abnormal development of dendritic spines in FMR1 knock‐out mice. J Neurosci 21, 5139–5146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliet SH., Malenka RC, Nicoll RA & RA N (1997). Two distinct forms of long‐term depression coexist in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neuron 18, 969–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweil EK, Krueger DD, Reinhold K & Bear MF (2010). Hypersensitivity to mGluR5 and ERK1/2 leads to excessive protein synthesis in the hippocampus of a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci 30, 15616–15627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Bellone C & Zhou Q (2013). NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 14, 383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradee W, Melikian HE, Rasmussen DL, Kenneson A, Conn PJ & Warren ST (1999). Fragile X mouse: strain effects of knockout phenotype and evidence suggesting deficient amygdala function. Neuroscience 94, 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauner C & Köhr G (2011). Triheteromeric NR1/NR2A/NR2B receptors constitute the major N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate receptor population in adult hippocampal synapses. J Biol Chem 286, 7558–7566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakimura K, Kutsuwada T, Ito I, Manabe T, Takayama C, Kushiya E, Yagi T, Aizawa S, Inoue Y, Sugiyama H & Mishina M (1995). Reduced hippocampal LTP and spatial learning in mice lacking NMDA receptor ε1 subunit. Nature 373, 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schütt J, Falley K, Richter D, Kreienkamp H‐J & Kindler S (2009). Fragile X mental retardation protein regulates the levels of scaffold proteins and glutamate receptors in postsynaptic densities. J Biol Chem 284, 25479–25487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Wang H, Mercaldo V, Li X, Chen T & Zhuo M (2009). Fragile X mental retardation protein is required for chemically‐induced long‐term potentiation of the hippocampus in adult mice. J Neurochem 111, 635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidorov MS, Auerbach BD & Bear MF (2013). Fragile X mental retardation protein and synaptic plasticity. Mol Brain 6, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CM, Alekseyenko O, Hamilton SM, Thomas AM, Serysheva E, Yuva‐Paylor LA & Paylor R (2011). Modifying behavioral phenotypes in Fmr1KO mice: genetic background differences reveal autistic‐like responses. Autism Res 4, 40–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprengel R, Suchanek B, Amico C, Brusa R, Burnashev N, Rozov A, Hvalby O, Jensen V, Paulsen O, Andersen P, Kim JJ, Thompson RF, Sun W, Webster LC, Grant SG, Eilers J, Konnerth A, Li J, McNamara JO & Seeburg PH (1998). Importance of the intracellular domain of NR2 subunits for NMDA receptor function in vivo. Cell 92, 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toft AKH, Lundbye CJ & Banke TG (2016). Dysregulated NMDA‐Receptor Signaling Inhibits Long‐Term Depression in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. J Neurosci 36, 9817–9827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar KR, McGinley MJ & Westbrook GL (2013). Triheteromeric NMDA receptors at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci 33, 9150–9160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner G, Webb T, Wake S & Robinson H (1996). Prevalence of Fragile X Syndrome. Am J Med Genet 64, 196–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk AJ, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Reiner O, Richards S, Victoria MF, Zhang FP, et al (1991). Identification of a gene (FMR‐1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell 65, 905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie DJA, Livesey MR & Hardingham GE (2013). Influence of GluN2 subunit identity on NMDA receptor function. Neuropharmacology 74, 4–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Chen R‐Q, Gu Q‐H, Yan J‐Z, Wang S‐H, Liu S‐Y & Lu W (2009). Metaplastic regulation of long‐term potentiation/long‐term depression threshold by activity‐dependent changes of NR2A/NR2B ratio. J Neurosci 29, 8764–8773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan QJ, Asafo‐Adjei PK, Arnold HM, Brown RE & Bauchwitz RP (2004). A phenotypic and molecular characterization of the fmr1‐tm1Cgr Fragile X mouse. Genes, Brain Behav 3, 337–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan QJ, Rammal M, Tranfaglia M & Bauchwitz RP (2005). Suppression of two major Fragile X Syndrome mouse model phenotypes by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropharmacology 49, 1053–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro K & Philpot BD (2008). Regulation of NMDA receptor subunit expression and its implications for LTD, LTP, and metaplasticity. Neuropharmacology 55, 1081–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Low C, Moody OA, Jenkins A & Traynelis SF (2015). Ionotropic GABA and glutamate receptor mutations and human neurologic diseases. Mol Pharmacol 88, 203–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalfa F et al. (2003). The Fragile X Syndrome protein FMRP associates with BC1 RNA and regulates the translation of specific mRNAs at synapses. Cell 112, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalfa F, Achsel T & Bagni C (2006). mRNPs, polysomes or granules: FMRP in neuronal protein synthesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol 16, 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M‐G, Toyoda H, Ko SW, Ding H‐K, Wu L‐J & Zhou M (2005). Deficits in trace fear memory and long‐term potentiation in a mouse model for Fragile X Syndrome. J Neurosci 25, 7385–7392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]